Abstract

We evaluated the effects of redistribution and swallow facilitation with a flipped spoon on packing in 2 children with a feeding disorder. For both participants, packing decreased when we implemented the flipped spoon treatment package. Mechanisms responsible for behavior change and areas of future research are discussed.

Keywords: escape extinction, feeding disorders, flipped spoon, negative reinforcement, packing, pediatric feeding disorders

Packing (holding food in the mouth without swallowing) is a problem behavior that may result in decreased oral intake, longer meal durations, and aspiration (Gulotta, Piazza, Patel, & Layer, 2005). Gulotta et al. used redistribution to reduce the packing of four children. Redistribution consisted of removing packed food from the child's mouth and placing it back on the tongue with a Nuk brush. Hoch, Babbitt, Coe, Duncan, and Trusty (1995) reported that mouth clean (the converse of packing) increased when the feeder deposited bites by depressing a Nuk brush on the posterior of the child's tongue while moving the brush forward on the tongue and out of the mouth. Hoch et al. hypothesized that stimulating the rear portion of the tongue increased the probability of swallowing (i.e., swallow facilitation).

In the current study, we combined the procedures (redistribution and swallow facilitation) described by Gulotta et al. (2005) and Hoch et al. (1995) to treat the packing of two children. In both the Gulotta et al. and Hoch et al. studies, feeders used a Nuk brush during redistribution and swallow facilitation. The brush is an ideal tool for these procedures because its narrow, bristled head allows the feeder to deposit the bite on and provide stimulation to the child's tongue. A disadvantage of the brush is that it is not a utensil used by typically eating children. An alternative to the brush is to redistribute and facilitate swallowing of the packed food with a flipped spoon (Sharp, Harker, & Jaquess, 2010). Although Sharp et al. used a flipped spoon to reduce expulsions in one child, we could find no studies evaluating redistribution and swallow facilitation with a flipped spoon as treatment for packing. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to determine the effectiveness of redistribution and swallow facilitation with a flipped spoon to decrease packing.

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Tracey was a 4-year-old girl whose medical history included failure to thrive, reflux, nasogastrostomy-tube dependence, and food refusal. Jordan was a 5-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with autism, reflux, and food selectivity by type and texture. Both children were treated in an outpatient program. Sessions were conducted approximately once per week for an hour in a room that contained a booster seat (Tracey) or toddler high chair (Jordan), utensils, a table, and chairs. The room was also equipped with one-way observation and sound.

Data Collection and Interobserver Agreement

Packing was defined as any food, pea size or larger, that remained in the child's mouth 30 s after the bite entered the child's mouth. Observers used laptop computers to record the occurrence or nonoccurrence of packing once for each bite presentation and converted the occurrence data to a percentage after dividing the number of packs by the number of bites that entered the child's mouth. Two individuals simultaneously but independently collected data on packing during 43% and 50% of sessions for Tracey and Jordan, respectively. Interobserver agreement was calculated by summing occurrence (both observers scored the occurrence of the behavior) and nonoccurrence (both observers did not score an occurrence of the behavior) agreements; dividing by the sum of occurrence agreements, nonoccurrence agreements, and disagreements (one observer scored the occurrence and the other observer did not score an occurrence of the behavior); and converting this ratio to a percentage. Mean agreement for packing was 100% for Tracey and 98% (range, 91% to 100%) for Jordan.

Procedure and Design

Prior to this investigation, we implemented nonremoval of the spoon (NRS; Ahearn, Kerwin, Eicher, Shantz, & Swearingin, 1996) with both children to increase consumption of a variety of pureed foods (table foods blended until smooth). Packing emerged when, as part of the treatment progression, we increased texture to wet ground (pureed food with small chunks) for Tracey and finely chopped (food cut into rice-size pieces with no liquid base) for Jordan. These higher textures were presented during the analysis described below.

During each session, the feeder presented four foods (one from each of the food groups of protein, starch, vegetable, and fruit) in a random order. The feeder presented one bite approximately every 30 s and a total of five bites. The feeder used NRS for both children throughout the current analysis. The feeder presented a level small Maroon spoonful of food in an empty bowl on the table in front of Tracey and waited 5 s for her to place the bite in her mouth. If she did not place the bite in her mouth within 5 s, the feeder used a partial physical prompt to guide Tracey's hand to hold the spoon 4 cm from her lips and then released her hand. If Tracey did not place the bite in her mouth within 5 s of the partial physical prompt, the feeder guided her hand so that the spoon touched her lips. The feeder held the spoon with Tracey's hand on it at her lips until the bite entered her mouth. The feeder presented approximately 25 rice-size pieces of food on a small Maroon spoon to Jordan's lips. The spoon remained at Jordan's lips until the bite entered his mouth.

The feeder provided brief verbal praise if Tracey fed herself the entire bite within the first 5 s of presentation or following the partial physical prompt, if Jordan accepted the entire bite within 5 s of presentation, and if no food pea size or larger was in the child's mouth 30 s after the bite entered the mouth. The feeder ignored inappropriate behavior and re-presented expelled bites. The feeder prompted the child to “show me” 30 s after the bite entered the child's mouth to determine if the child was packing. If the child did not open his or her mouth, the feeder repeated “show me” and used the spoon to physically guide the child to open his or her mouth. An ABAB design was used to evaluate the effects of the flipped spoon on packing.

During baseline, if the child was packing the bite at the 30-s check, the feeder prompted the child to “swallow your bite” and presented the next bite immediately. If the child was packing after the feeder had presented the fifth bite, the feeder checked the child's mouth every 30 s and prompted the child to “swallow your bite” until the collective amount of food in the child's mouth was smaller than the size of a pea, at which point the session ended.

The flipped spoon procedure was similar to baseline. In addition, 20 s (Tracey) or 15 s (Jordan) after the bite entered the child's mouth, the feeder checked the child's mouth and implemented the flipped spoon (without a verbal prompt) if any food pea size or larger was visible in the child's mouth. The feeder collected the food from the child's mouth onto the spoon, inserted the spoon into the child's mouth, rotated the spoon 180°, and deposited the food by applying slight downward pressure behind the middle of the child's tongue while dragging the spoon towards the front of the tongue. The feeder stopped the 30-s timer during the flipped spoon because the child was not able to consume the bite during implementation. The feeder restarted the timer after implementing the flipped spoon. The feeder checked the child's mouth 30 s after the bite initially entered the mouth, repeated the flipped spoon procedure if the child was packing, prompted the child to swallow, and presented the next bite. If the child packed the fifth bite, the feeder implemented the flipped spoon and prompted the child to swallow every 30 s until no food pea size or larger was in the child's mouth, at which point the session ended. Jordan always masticated the food 15 s after acceptance, so the flipped spoon could be implemented safely.

Therapists taught Tracey's mother to implement the flipped spoon, and observers collected follow-up data 3 weeks after her mother began implementing the flipped spoon procedure at home.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

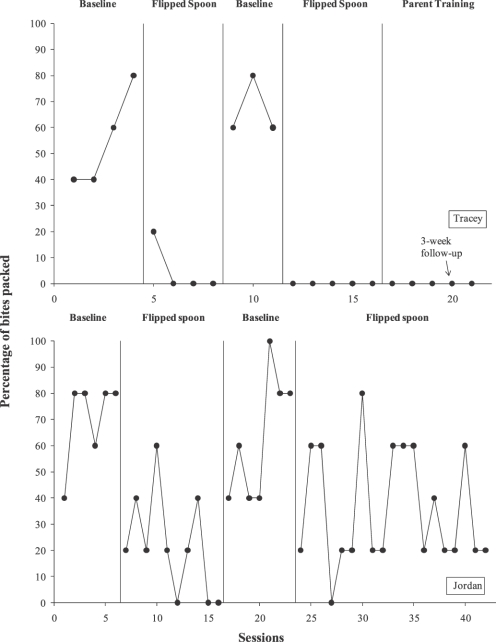

Packing (Figure 1) was high during the initial baseline for Tracey (M = 55%; range, 40% to 80%) and Jordan (M = 70%; range, 40% to 80%). Packing decreased to low levels for Tracey (M = 5%; range, 0% to 20%) and to lower and more variable levels for Jordan (M = 22%; range, 0% to 60%) during the flipped spoon. During the reversal to baseline, packing increased for Tracey (M = 67%; range, 60% to 80%) and Jordan (M = 63%; range, 40% to 100%). When the flipped spoon was reintroduced, packing decreased for Tracey (M = 0%) and Jordan (M = 36%; range, 0% to 80%). Packing remained at zero during parent training and the 3-week follow-up for Tracey. Total acceptance was 100% for both participants during all phases of the analysis (data not shown). Mean session length during baseline was 5.3 min (Tracey) and 4.9 min (Jordan). During the flipped spoon procedure, mean session length was 4.1 min (Tracey) and 4.9 min (Jordan), representing either a decrease (Tracey) or no change (Jordan) in length.

Figure 1.

Percentage of bites packed for Tracey (top) and Jordan (bottom).

In previous studies on redistribution and swallow facilitation, feeders used a Nuk brush to redistribute packed food (Gulotta et al., 2005) or to facilitate a swallow (Hoch et al., 1995). The current study extends previous work by showing that an alternative utensil, the flipped spoon, also is effective for redistribution and swallow facilitation. The Nuk brush has the advantage of a small bristled head, which is easily inserted into the mouth and allows the feeder to deposit the bite directly on the tongue. However, the spoon is a more typical utensil for a child. Although we flipped the spoon, which is less typical, it still may be more preferable to caregivers than the brush, which is not used by typically eating children. In addition, the wider surface area of the spoon results in greater contact with the tongue, which may be advantageous for flattening the tongue during redistribution and swallow facilitation. However, we did not compare the effectiveness of the Nuk brush and flipped spoon, which should be a direction for future research.

As in previous studies, the operant mechanism underlying the effects of the flipped spoon remains unknown. One possibility is that punishment, negative reinforcement, or both accounted for the treatment outcomes (Gulotta et al., 2005; Patel, Piazza, Layer, Coleman, & Swartzwelder, 2005). That is, the flipped spoon may have functioned as positive punishment for packing. If the flipped spoon procedure was more aversive than swallowing, the child also may have learned to swallow the bite to avoid the flipped spoon. An indirect analysis of within-session data for latency to mouth clean (i.e., length of time between entire bite entering the child's mouth and when the child's mouth contained food smaller than the size of a pea) for Tracey indicated that, on average, she swallowed prior to implementation of the flipped spoon (approximately 20 s following acceptance) on four of five trials. In addition, packing decreased rapidly, and she packed only once during the flipped spoon treatment phase. These data suggest that she learned to avoid the flipped spoon by swallowing and that the flipped spoon functioned as punishment for holding food in her mouth.

Alternatively, children may pack food because they lack the skills essential for swallowing (Gulotta et al., 2005; Patel et al., 2005). Lamm and Greer (1988) observed that touching the right posterior portion of the tongue resulted in arching of the tongue and reported improved swallowing in children who had difficulty with this skill. Similarly, in the current study, using the flipped spoon to collect the packed food and place it on the back of the child's tongue may have aided bolus formation. In addition, the application of downward pressure on the back of the child's tongue while moving the spoon forward may have facilitated bolus propulsion, thereby facilitating the swallow. This explanation seems more applicable to Jordan's data, because his packing never decreased to zero for more than one session and the decrease in packing was gradual. He appeared to require the aid of the flipped spoon to swallow.

A final possible explanation for the treatment effect of the flipped spoon is that placing the bolus on the back of the tongue made it more difficult for the child to pack. Therefore, it is possible that packing decreased because of the increased response effort (Patel et al., 2005).

A limitation of the current study is that a mouth check was not conducted at 15 s or 20 s in baseline. It is possible that the check alone may have resulted in decreased packing. We also conducted redistribution and swallow facilitation as a package. Future studies should correct these limitations and isolate the effects of the various procedures. For children with a skill deficit, it is unclear whether the flipped spoon procedure would need to be faded or if independent swallowing would begin to occur over time. Future studies should determine the necessity of and method for fading the flipped spoon. An additional limitation is that the flipped spoon procedure may not be appropriate or safe with a child who does not chew more advanced textures (e.g., chopped or table food), which was not the case in this study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Haley Hall and Erin Feind for their assistance with this study.

REFERENCES

- Ahearn W.H, Kerwin M.E, Eicher P.S, Shantz J, Swearingin W. An alternating treatments comparison of two intensive interventions for food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:321–332. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulotta C.S, Piazza C.C, Patel M.R, Layer S.A. Using food redistribution to reduce packing in children with severe food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:39–50. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.168-03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch T.A, Babbitt R.L, Coe D.A, Duncan A, Trusty E.M. 1995. A swallow induction avoidance procedure to establish eating. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 26(1) 41 50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm N, Greer D. Induction and maintenance of swallowing responses in infants with dysphasia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;21:143–156. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1988.21-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M.R, Piazza C.C, Layer S, Coleman R, Swartzwelder D. A systematic evaluation of food textures to decrease packing and increase oral intake in children with pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:89–100. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.161-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp W.G, Harker S, Jaquess D.L. Comparing bite presentation methods in the treatment of food refusal. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:739–743. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]