Abstract

Lymphatic malformation is an uncommon anomaly that commonly occurs in the posterior triangles of infants. The case presented here was an adult male patient with swelling in submental region. This site often leads to misdiagnosis of other common pathology including plunging ranula or lipoma. However, USG and MRI were done for diagnosis of the lesion by which final diagnosis of lymphatic malformation was made. Surgical excision was carried out and histopathology confirmed the primary diagnosis. No recurrence is seen in one and half year follow-up period.

Keywords: Lymphatic malformation, Posterior triangle, Submental, USG, MRI, Surgical excision

Introduction

Lymphangioma are benign proliferative developmental anomalies of lymphatic system [1–3]. The nature of lymphatic malformations (LM) has sparked great interest since they were first described by Redenbacher in 1828 [4]. Many of the early researchers believed that lymphatic malformations were neoplasms [5]. Currently, most researchers agree that LM are not neoplastic and have adopted the term “lymphatic malformation” to emphasize this fact [6].

The lymphatic system arises from 6 primitive sacs that develop at 6th week of intrauterine life. First pair is jugular sac, second pair is cysterna chyli located at retroperitoneal tissues, and third pair is posterior lymph sacs develop at inguinal region.

There are four views for pathogenesis. Most embryologists accept Sabin’s ‘sprouting’ phenomenon of endothelial lined out pocketing from the veins. Some people do not agree with Sabin’s view (Huntington) [7].

In history if we focus, from 1843 various authors have described lymphatic malformation as neoplastic variety to various different anomalies [7]. Ninety percent of the lesions arise at birth or till age of 2 years [2, 8].

Head and neck is a common site of involvement [6]. 50–60% of these lesions are present at birth, while 80–90% will be evident by age of 2 years [6]. Bill and Sumner [9] reported incidence as 5 per 3,000 but according to some it is quite less [10]. lymphatic malformation represent less than 5% of all congenital neck masses in children and even smaller amount in adults [10].

Various classification systems have been suggested by authors. From Watson and McCarthy [7] to Mulliken and Glowacki [11] and its modification by Jackson et al. [12] variation in description can be noticed. McGill and Mulliken [13] classified them into two types on anatomical basis according to relation with mylohyoid muscle. Basically that can be divided into capillary, cavernous, cystic hygromas and mixed variety as per endothelial characteristics which determine flow within the lesion [11]. Jackson divided vascular malformations into two types as per flow characteristics: high flow and low flow; management of two differs exquisitely. Lymphatic malformations were classified as low flow lesions [12].

A few cases have been reported in the adult population but incidence is very low compared to that of children [14–16]. History of trauma has been suggested as etiology in adults [17]. The case presented here belongs to infra-mylohyoid group variety of isolated localized malformation in an adult patient; the site of involvement i.e., anterior triangle and age of occurrence are unusual from cases reported. Such site of involvement often create clinical dilemma for diagnosis i.e., with other common swellings in the area.

Case Report

A 24-year male reported to the maxillofacial surgery department at Nair Hospital Dental College (NHDC), Mumbai with the complaint of a painless swelling in the submental region with one year duration.

There was no history of trauma, no history of associated pain or tenderness, fever, dysphagia, change in voice found, the swelling developed gradually and no history of increase or decrease in size of swelling noticed from onset.

The patient was earlier evaluated by FNAC at a private hospital with a suggested impression of inflammatory cystic lesion and due to unavailability of head and neck surgery services patient was referred to NHDC.

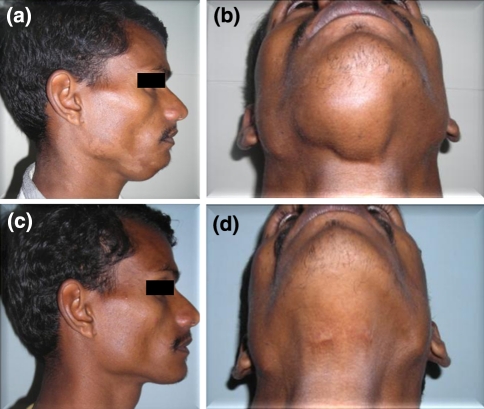

On examination, an irregularly oval swelling in the submental region measuring 4 × 6 cm in size was noted. The lesion extended vertically about 1 cm posterior from chin to hyoid, and horizontally 1 cm away from left mandibular border to right mandibular border. The skin over the swelling appeared apparently normal. Co-incident dermatophytic infection (Tinea versicolor) was found. On palpation, the swelling was soft and fluctuant but showed well defined edges. Neither pulsation nor bruit was noted. The swelling did not move with deglutition or protrusion of the tongue. Neck examination for lymph node fails to identify any pathology (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Profile of (a) Pre operative photograph (c) Post operative photograph after 1 year. Worm’s View of (b) Pre operative photograph (d) Post operative photograph after 1 year

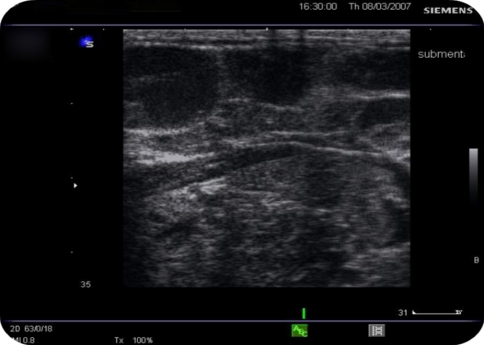

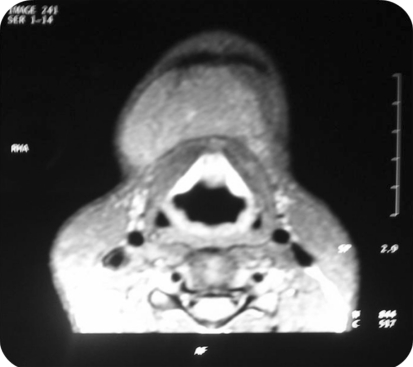

Differential clinical diagnosis of plunging ranula and dermoid cyst were made and it was decided to go for further imaging. Ultrasonography (USG) showed a multilocular cystic lesion with fluid levels. The lesion was not associated salivary gland (ranula ruled out) and due to presence of fluid dermoid cyst was ruled out. On Doppler high vascular flow was not noted so possibility of low flow lesion was suspected. Aspiration of the swelling showed clear fluid which was microscopically showing lymphocytes, and few blood cells. Multiple fluid levels and septations were noted on T2 signals (hyper-intense) on magnetic resonance imaging. Swelling did not appear to show any feeder vessel. STIR scan ruled out keratin containing lesions. So, Clear fluid on aspiration (no blood), absence of feeder vessel, fluid levels with septations and low flow ruled out vascular malformation and diagnosis of lymphatic malformation was made (Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Fig. 2.

Pre operative USG

Fig. 3.

MRI T1 weighed image sagittal section

Fig. 4.

MRI T1 weighed image axial section

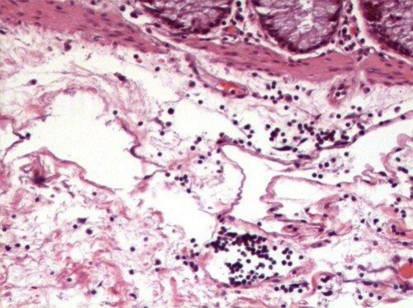

Patient was prepared for general anesthesia and surgical excision was carried out through percutaneous incision. No vascular structures were found approximating pathology. Lesion was found adherent to the bed and surrounding structures had tendency to rupture. It was excised by sharp and blunt dissection and was sent for biopsy. Histopathological examination showed multiple lymphatic like structures and lymphocytes suggestive of lymphatic malformation (Figs. 5, 6, 7).

Fig. 5.

Surgical specimen

Fig. 6.

Immediate post operative photograph

Fig. 7.

Histopathological picture (H&E stained) showing lymphocytes

Patient has had no recurrence of the lesion in the follow-up period of one and half years.

Discussion

In the literature nearly all reported cases of the lymphatic malformation are diffuse cystic hygroma in the posterior triangle of the neck in infants or newborns. History of trauma may be associated with some lesions [2, 18–22], but in present case no significant history of trauma was found.

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is found non-conclusive in most cases but gross appearance of the aspirate has guided us in reaching diagnosis. Absence of rapidly filling arterial blood confirms diagnosis of low flow lesion. USG is primary inexpensive nonionising, noninvasive imaging modality [2]. In our case USG with Doppler could reach the diagnosis. USG has high sensitivity for lesions of neck including, dermoid cyst, lipoma, plunging ranula, high-flow arteriovenous malformation [23–26].

Lionel Gold [26] evaluated role of USG with Doppler as an adjunct to CT and MRI and he reported good sensitivity of USG and he concluded that non-enhanced MRI with Doppler can give best diagnosis with reduced cost. In the present case MRI hardly gave more diagnostic information over Doppler but information about exact extent of the lesion and relation with adjacent structures and vasculature could be gained. For superficial lesions that can be scanned with USG may obviate need for further MRI but for deeper lesions Doppler’s use is limited [25–27]. Contrast enhanced CT has similar sensitivity to MRI for diagnosis [26].

Lymphopenia may be an associated feature with this kind of malformations [28] however this case had normal blood counts. Gorham Syndrome or vanishing bone syndrome is a type of lymphatic malformation that also involves the bone and surrounding tissue. It is a serious condition that results in significant bone loss and other complications [10].

Treatment of lymphatic malformation differs that from other vascular malformations. Different treatment modalities have been suggested by various authors including, aspiration, radiation, sclerosants, and surgery. Aspiration is done only to relieve pressure in large lesion [29]. Radiation is not used currently [30]. Sclerosants for example, OK-432 [1, 12], Bleomycin [31] have been tried with satisfactory results in some patients but use is not definitive. LASER or radiofrequency ablation can be used for excision [2]. Surgery is a more definitive treatment modality for lymphatic malformation [2, 31]. In the present case lesion was superficial and there was no risk for damage of vital structures of major vessels and was not causing severe morbidity so surgery can be advised as it is a definitive modality. While for larger cases encroaching vital structures or one that could cause severe postsurgical morbidity other methods should be given a chance.

Microscopically two types have been described: macrocystic and microcystic. Macrocystic lesions are large soft lesions having cysts more than 2 cm that respond well to sclerosing agents while microcystic lesions are small raised masses which can be treated by surgery [1]. Histopathologically the lesion was showing epithelial lined structures with lymphocytes and red cells. Macrophages with hemosiderin are characteristic of hemangioma and not seen in malformations. Large cystic spaces may be seen in cystic cases and blood vessels are also commonly encountered as both develop in proximity [11].

Recurrence rate is found to be 10–38% and is directly related to the excisional surgery [2].

Conclusion

Diagnostic difficulty may arise according to peculiar region in the present case dilemma about presence of common pathology e.g., ranula or dermoid cyst was there and the final diagnosis was not in our list of differential diagnosis; as a few cases have been reported of lymphatic malformation and is exceedingly rare especially in adults. Lymphatic malformation may contain vascular component so that should be ruled out before putting a knife. The MRI reported by a radiologist said that as venolymphatic malformation; which was questioning vascular flow of the lesion as opposed by Doppler report, consultation with other radiologist and close observation of the scan revealed that to be low flow lesion without any vascular component. Difficulty may encounter during surgery as spaces tends to rupture but recurrence is not seen commonly. Thus, this paper helps clinician to add one in the list of differential diagnosis.

References

- 1.Smith R, Burke DK, et al. OK-32 therapy for lymphangiomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1195–1199. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890230041009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandel L. Parotid area lymphangiomas in an adult: case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(10):1320–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey CM. Cystic hygroma. Lancet. 1990;335:511–512. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy TL. Cystic hygroma-lymphangioma: a rare and still unclear entity. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:1–9. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198910001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farmand M, Kuttenburg JJ, et al. A new therapeutic concept for the treatment of cystic hygroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Oral Endod. 1996;81(4):389–395. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serres MD, Sie KCY, et al. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck: proposal for staging. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(5):577–582. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890050065012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palleta FX. Lymphangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37(4):269–279. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grabb WC, Dingman RO, et al. Facial hamartoma in children: neurofibroma, lymphangioma, and hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66(4):509–527. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198010000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bill AH, Sumner DS. A unified concept of lymphangioma and cystic hygroma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado LE, Osborne NG, Bonilla-Musoles F. Three-dimensional sonographic diagnosis of a large cystic neck lymphangioma. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23(6):877–881. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.6.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a new classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:412–422. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson IT, Carreno R, et al. Hemangiomas, lymphatic malformations and lymphovenous malformations: classification and methods of treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(7):1216–1230. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGill T, Mulliken J. Vascular anomalies of the head and neck. otolaryngology head and neck surgery. Baltimore: Mosby-Year Book; 1993. pp. 333–346. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman P, Yeung CS, Batsakis JG. Retropharyngeal lymphangioma presenting in an adult. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103(3):476–479. doi: 10.1177/019459989010300323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schefter RP, Olsen KD, Gaffey TA. Cervical lymphangioma in the adult. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(1):65–69. doi: 10.1177/019459988509300113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muñoz Herrera A, Pérez Plasencia D, Gómez Benito M, Santa Cruz Ruiz S, Flores Corral T, Aguirre García F. Cervical lymphangioma in adults- Description of 2 cases. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1998;115(5):299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aneeshkumar MK, Kale S, Kabbani M, David VC. Cystic lymphangioma in adults: can trauma be the trigger? J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:566–568. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0780-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toranzo JM, Guerrero F, et al. A congenital neck mass. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1996;82(4):363–364. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osborne TE, Alex Haller J, et al. Submandibular cystic hygroma resembling a plunging ranula in a neonate—review and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90513-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saijo M, Munro IR, Mancer K. Lymphangioma—a long term follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:642–651. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fraser SE, Campbell B, et al. Pathologic quiz 2. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson JW, Meszaros EJ. Submucosal lymphangiomas of the maxillary sinus. J Oral Maxillofac Surgery. 2003;61:390–392. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gold L, et al. US Doppler for vascular anomalies. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:27–31. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.29069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oates CP, Wilson AW, Ward-booth RP, et al. Combined use of Doppler and conventional ultrasound for the diagnosis of vascular and other lesions in the head and neck. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19(4):235–239. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80400-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida H, Yusa H, et al. Use of Doppler color flow imaging for differential diagnosis of vascular malformations. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:369–374. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90706-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gold L, et al. Characterization of maxillofacial soft tissue vascular anomalies by ultrasound and color Doppler imaging: an adjunctive to computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(1):19–31. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung K, Poenaru D, et al. Impact of magnetic resonance imaging on the surgical management of cystic hygromas. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(6):839–841. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90654-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins JA, Tempero RM, Hannibal MC, Manning SC. Clinical outcomes in lymphocytopenic lymphatic malformation patients. Lymphatic Res Biol. 2007;5:169–174. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.5304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emery PJ, Bailey CM, Evans JNG. Cystic hygroma of the head and neck. J Laryngol Otol. 1984;98:613–619. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100147176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goshen S, Ophir D. Radiology in focus, cystic hygroma of the parotid gland. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107(9):855–857. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100124636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickerhoff R, Bode U. Cyclophosphamide in non-resectable cystic hygroma. Lancet. 1990;335:1474–1475. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]