Abstract

Background

This study sought to determine the efficacy of interpositional arthroplasty with temporalis muscle and fascia flap in the treatment of unilateral temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis in adults.

Methods

This retrospective study of nine cases evaluated the postoperative results of interpositional arthroplasty on temporalis muscle and fascia flap in adults. The operative protocol for unilateral TMJ ankylosis entailed (1) resection of ankylotic mass, (2) intraoral ipsilateral coronoidectomy, (3) contralateral coronoidectomy when necessary, (4) interpositional tissue transfer to the TMJ with temporalis muscle, fascia flap, and (5) early mobilization, aggressive physiotherapy.

Results

The study evaluated nine patients with follow-up checks from 13 to 31 months (mean 18.3 months). Patients had a preoperative maximal interincisal opening of 9–19 mm (mean 11.7 mm). During the last follow-up observation after surgery, the patients had a maximal interincisal opening of 35–40 mm (mean 38.3 mm).The results of this protocol were encouraging, the functional results of interpositional arthroplasty on temporalis muscle and fascia flap were also satisfactory.

Conclusion

The findings of this study support the use of temporalis muscle and fascia flap in adult patients with unilateral TMJ ankylosis. Early postoperative initial exercise, physiotherapy and strict follow-up play an important role in preventing postoperative recurrences.

Keywords: Ankylosis, Temporalis muscle, Fascia flap, Temporomandibular joint

Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis is a very painful condition with deficient esthetics that leads to malnutrition of the patient due to inability of normal eating. It also causes speech inability. Ankylosis of TMJ can also cause severe psychological distress aggravates psychological stress [9, 13, 19]. TMJ ankylosis during early childhood may lead to disturbances in growth, or cause asymmetry and serious difficulties in eating and breathing during sleep [20, 26]. The causative factors of TMJ ankylosis are trauma, systemic and local inflammatory conditions, neoplasm in TMJ area. Ankylosis can be relieved by surgical treatment [32, 33].

Management of TMJ ankylosis is mainly through surgical intervention. It is necessary to use an inter positional material to prevent TMJ re-ankylosis after arthroplasty, and this particular aspect of the treatment has been the subject of numerous discussions. A variety of interposition materials have been used, including temporalis muscle and fascia, dermis, auricular cartilage, fascia lata, fat, lyo-dura, silastic, silicone, and various metals [21, 23, 34, 35].The most commonly used interposition material is temporalis muscle flap. A number of surgical approaches have been devised to restore normal joint functioning, but the surgical intervention for TMJ ankylosis is frequently followed by re-ankylosis, occlusal disturbance, retrusion of the mandible, sleep dyspnea, and alternation of functional masticatory movement. The most frequently reported complications after treatment of ankylosis are limited mouth opening and re-ankylosis. These can be prevented by aggressive re-sectioning of the bony or fibrous segment, especially in the medial aspect of the TMJ [18]. The present study sought to examine the effectiveness of inter positional arthroplasty with temporalis muscle and fascia flap in the treatment of unilateral TMJ ankylosis in nine patients.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective evaluation of nine patients treated consecutively was conducted. There were seven men and two women, with a mean age of 24.7 years (range 21–32). The maximum interincisal opening was 9–19 mm. Radiographic assessment was carried out using Computed Tomography (CT) scan and orthopantomograph. The patients were operated on for a period of 3 years, applying the same protocol and techniques. The operative protocol for unilateral TMJ ankylosis in adults consisted of: (1) resection of ankylotic mass through preauricular incision with temporal extension (Alkayat-Bramley incision), approximately around 1.5–2 cm of ankylotic mass was removed by using piecemeal technique; (2) intraoral ipsilateral coronoidectomy and (3) contralateral coronoidectomy where done when mouth opening intraoperatively was less than 35 mm; Ipsilateral coronoidectomy was done using the same approach and contralateral coronoidectomy was done using intraoral approach. (4) Inferiorly based, U-shaped, fingerlike temporalis muscle and fascia flap was turned outwards and downwards over the zygomatic arch and placed in the TMJ and (5) early mobilization, aggressive physiotherapy. General anesthesia with blind nasotracheal intubation and total muscle relaxation was administered. A single i.v. dose of steroid was given at the start of the case, generally using 8–12 mg of prednisolone. A preauricular incision with a temporal extension was made. The external auditory canal was lightly packed with vaseline gauze. The temporalis muscle was lifted from the infratemporal fossa toward the anterior at the pericranial level, while the zygomatic root was uncovered. An avascular tissue plane along the cartilaginous meatus was established using surgical scissors. The ankylosed TMJ was palpable and an incision was made directly onto the bone, exposing the ankylosed TMJ. Excision of the fibrous tissue and ankylotic bony mass was carried out using drill and saw. The TMJ was lined with a temporalis muscle and fascia flap rotated over the arch into the joint. The flap was sutured medially, anteriorly, and posteriorly with 4-0 Vicryl. Prednisolone was also given intra-, and postoperatively (8–12 mg). Postoperative antibiotics and pain medications, vigorous postoperative physiotherapy were performed to maintain the mobility obtained during surgery and to prevent postsurgical hypomobility secondary to fibrous adhesions. The patients were started on a soft diet and jaw-opening exercises using stacked tongue depressors and bilateral rachet mouth props after the release of ankylosis. Physiotherapy was started once a day for the first 2 weeks and once every 2 days for the following 2 weeks. Physiotherapy was continued for several months if deemed necessary.

Results

The study evaluated seven patients with follow-up checks from 13 to 31 months (mean 18.3 months). Trauma was the most common cause of ankylosis (77.7%), and the 19–32 years-old age group displayed the most trauma cases. Patients had a preoperative maximal interincisal opening (Fig. 1) of 9–19 mm (mean 11.7 mm). During the last follow-up observation after surgery, the patients had a maximal interincisal opening of 35–40 mm (mean 38.3 mm). Seven patients underwent coronoidectomy, while two patients (cases 3, 4) underwent bilateral coronoidectomies. Maximal mouth opening during the surgery was at an average of 38 mm. The postoperative orthopantomograph in five patients (Fig. 2) showed an increased interarticular space due to the interposed tissue without signs of relapse of ankylosis. There was no change in occlusion except for anterior open bite in three cases which resolved subsequently after regular physiotherapy Repetitive operation was not carried out and no complications were noted. All patients displayed uneventful healing with a smooth postoperative course and a marked improvement in mouth opening. A summary of results is shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative frontal view of the patient

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative photograph showing maximum interincisal opening of the patient

Table 1.

Summary of temporomandibular joint ankylosis cases

| Patients | Age (years) | Sex | Aetiology | MIO (mm) | Change (mm) | Duration of follow-up (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preop | Postop | ||||||

| 1 | 26 | M | Trauma | 9 | 37 | 28 | 16 |

| 2 | 28 | M | Trauma | 11 | 40 | 29 | 17 |

| 3 | 21 | M | Trauma | 8 | 35 | 27 | 15 |

| 4 | 23 | M | Trauma | 10 | 39 | 29 | 31 |

| 5 | 29 | F | Trauma | 15 | 39 | 24 | 20 |

| 6 | 19 | M | Trauma | 19 | 40 | 21 | 14 |

| 7 | 32 | M | Trauma | 13 | 38 | 25 | 13 |

| 8 | 20 | F | Infection | 14 | 40 | 26 | 18 |

| 9 | 25 | M | Infection | 7 | 37 | 30 | 21 |

M Male, F female, MIO maximum incisal opening, Preop preoperative, Postop postoperative

Discussion

Ankylosis of the TMJ can be classified into true ankylosis (intracapsular) and pseudoankylosis (extracapsular). True ankylosis of the TMJ is defined as any condition that produces fibrous or bony adhesions between the articular surfaces of the TMJ. True ankylosis of the TMJ results from infection, trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, neoplasm, local surgical complications, chemical burns and extension of intracapsular ankylosis [2, 10, 11, 12]. Pseudoankylosis results from muscular, osseous, neurological, or psychiatric disorders. True ankylosis is most commonly associated with trauma or infection. Management of TMJ ankylosis entails surgical intervention. The need to use an inter positional material to prevent TMJ re-ankylosis after arthroplasty in treatment of TMJ ankylosis has been widely discussed [14, 15, 22, 28]. A variety of interposition materials have been used, including temporalis muscle and fascia, dermis, auricular cartilage, fascia lata, fat, lyodura, silastic, silicone, and various metals. The most commonly used interposition material at present is temporalis muscle flap [29, 30, 31].

Bergey and Braun [2] described how the posterior zygomatic arch can be osteotomized in two sites and a segment of the arch removed. The flap then may be rotated through the space created by the osteotomy into the joint and the segment of the arch replaced and secured with rigid fixation. Brusati et al. [3] used the temporalis muscle flap to treat the severely damaged TMJ structural components (ankylosis, arthrosis, tumor, perforation or degeneration of the disc). Using this surgical technique, 12 patients and 13 TMJs yielded positive functional results without any complication.

Chandra and Dave [4] reported 258 cases and found 67.8% associated with trauma and 17% with infection. Chidzonga [5] reported that the main cause of relapse was failure to carry out jaw-opening exercises. Therefore, postoperative exercises play a crucial role in ensuring lasting success.

Chossegross et al. [6] evaluated the result of inter positional materials placed in 25 patients (32 joints) with at least 3 years of follow-up. Good results were achieved in 92% of cases using total full-thickness skin graft and 83% of cases using temporal muscle flap. Homologous cartilage yielded poor results. Chossegross et al. [7], on the other hand, reported that early physiotherapy and choice of inter positional material are important in preventing recurrence. The immediate postoperative period is the most critical time for successful treatment of TMJ ankylosis. Postoperative pain medications, vigorous physiotherapy and CPM therapy are used to maintain the mobility obtained during surgery and to prevent postsurgical hypomobility secondary to fibrous adhesions 31. In the present study, MMF was maintained for a period of 3–7 days in order to provide relief from postoperative pain and swelling, as well as to provide flap stability. This was carried out for 3 days for most patients. In one patient, MMF was maintained 7 days to correct severe postoperative occlusal disturbance. The tongue blades were used for exercise while the rachet mouth prop were used to count the number of blades during each appointment. All patients underwent physiotherapy consisting of active and passive ranges of motion exercise at least once a day for the first 2 weeks and once every 2 days for the following 2 weeks. The patient’s diet at this time consisted of very soft foods. After release of MMF, patients were started on a soft diet. During the next 3–4 weeks the diet was gradually advanced to a solid consistency. As the diet regimen is advanced from a soft to a regular diet, patients are informed about the guidelines to assist them in making sure they do not overuse their jaw. It is important to note that early postoperative opening exercise, active postoperative physiotherapy, and strict follow-up are essential to prevent postoperative adhesions. In 1999, Chossegross et al. [7] evaluated 31 patients who had undergone interposition of a full-thickness skin graft at least 1 year after surgery and obtained a 90% success rate.

Clauser et al. [8] carried out reconstruction with the temporalis myofascial flap in 182 cases specifically for reconstructive cranio-maxillofacial surgery: trauma, deformities, tumors, TMJ ankylosis, facial paralysis. No major complications were observed. The use of this flap constitutes a quick, reproducible method of reconstruction associated with minimal morbidity. In 1989, Feinberg and Larsen [11] described a pedicled temporalis muscle and pericranial flap acting as an inter positional material in TMJ surgery. This flap was rotated in an anterior direction to the articular eminence and then posteriorly into the TMJ where it was sutured to the retrodiscal tissue. This procedure allows maintenance of tissue viability and functional movement of the flap during mandibular excursions.

Herbosa and Rotskoff [16] evaluated 15 TMJ patients preoperatively and postoperatively to evaluate the effectiveness of a composite (fascia, muscle and periosteum) temporalis pedicle flap as an inter positional disc replacement. Eighteen months after the operation, significant clinical improvement in the mandibular range of motion (P < 0.05) was observed. However, a significant reduction in translation (P < 0.01) was evident, indicating that the increased mandibular opening was due to a compensatory rotational movement. This study showed that the composite temporalis pedicle flap is a good autogenous tissue for the reconstruction of the TMJ. Kaban et al. [17] recommended a management protocol for TMJ ankylosis consisting of aggressive resection, ipsilateral coronoidectomy, contralateral coronoidectomy when necessary, lining of the TMJ with temporalis fascia or cartilage, reconstruction of the ramus with a costochondral graft, rigid fixation, and early mobilization and aggressive physiotherapy. The protocol was retrospectively evaluated in the first 14 patients (18 TMJs) treated and followed-up postoperatively for atleast 1 year. The facial asymmetries present in all unilateral cases remained corrected. The mean maximum postoperative interincisal opening at 1 year was 37.5 mm, lateral excursions were present in 16 of 18 joints (vs. none of the 18 joints preoperatively), and pain was present in two of 18 joints (vs. 13 of 18 preoperatively). The results of this study indicate that this protocol is effective for treatment of TMJ ankylosis.

Mani and Panda [24] reported that temporalis myofascial flap holds great promise for the reconstruction of various defects of the maxillofacial region-either congenital or surgical. The dependable blood supply through the middle and deep temporal arteries, proximity to the maxillofacial region, possibility to mobilize it to the oral cavity through the under surface of zygomatic arch and its fanned out nature permits the surgeon to use this flap for the reconstruction of various maxillofacial defects and even as an interposing tissue. In the series of 30 cases, they have used the temporalis myofascial flap for the reconstruction of different types of maxillofacial defects and as an interposing material in TMJ surgeries. They found that this flap is very valuable in maxillofacial reconstruction.

Balaji [1] evaluated the long-term outcomes and clinical results of costochondral graft and temporalis muscle flap interpositioning with submandibular anchorage in the management of TMJ re-ankylosis. Thirty-one patients, 9 children and 22 adults, with recurrence of ankylosis after gap arthroplasty, with a mouth opening less than 5 mm were evaluated. The management protocol consisted of resection of the ankylotic mass through an Al-Kayat and Bramley incision; contralateral coronoidectomy in unilateral cases; replacement of the condyle in children by means of a costochondral graft through Risdon’s approach and inter positional temporalis muscle flap and submandibular anchorage of the temporalis flap in children and adults. Regular clinical and radiological follow-up was done for 6 years during which the average mouth opening of 38 mm was maintained, with good occlusion and proper function. The temporalis muscle flap was seen to be an ideal inter positional material due to its close proximity to the site, good vascular supply, ease of access to the condyle area and minimal risk of nerve damage. Submandibular anchorage of the broad temporalis muscle flap prevents re-ankylosis by inhibiting flap contraction, and decreases need for rigorous physiotherapy.

Martins [25] reported a true bilateral ankylosis of the TMJ in a 19-year-old male patient who had a life-threatening ear infection at the age of ten resulting in a progressive restriction of his mouth opening. He presented with almost complete lack of mobility of the mandible. Surgical treatment was a resection of the ankylotic mass, interpositional temporalis composite muscle flaps, and early mobilization and aggressive physiotherapy. The functional results of an inter positional arthroplasty (Fig. 3) were excellent.

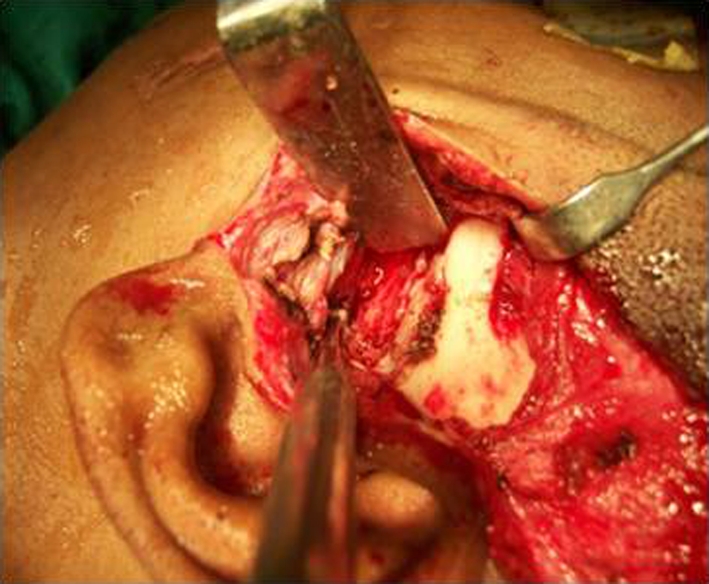

Fig. 3.

Intra-operative photograph showing release of ankylosis with inter positional arthroplasty using temporalis fascia and muscle

Mehrotra et al. [27] studied the advantages and disadvantages of dermis-fat graft as an interposition material after arthroplasty and compared it with temporalis fascia interposition. Seventeen patients with temporomandibular ankylosis involving 20 joints were randomly divided into two groups; the first group had operations for interposition of dermis-fat graft that was taken from the groin. Patients in control group had operations to interpose temporalis fascia and muscle from the same surgical site. All were assessed by age, sex, etiology, clinical features and post surgical complications. The groups were matched in age and the male: female ratio was 0.89:1. The median duration of ankylosis was 7.3 (range 2–11) years. Postoperative and follow-up interincisal mouth opening was satisfactory with good healing of the dermis-fat graft donor site. We conclude that the use of dermis-fat grafts has minimal donor site morbidity, and is a safe and effective interposition material to prevent the recurrence of temporomandibular ankylosis.

Kaban et al. [18] reported a case series of children with ankylosis treated at Massachusetts General Hospital. Their observation revealed that the most common cause of treatment failure is inadequate resection of the ankylotic mass (Fig. 4) and failure to achieve adequate passive maximal opening in the operating room. The 7-step protocol consisted of (1) aggressive excision of the fibrous and/or bony ankylotic mass, (2) coronoidectomy on the affected side, (3) coronoidectomy on the contralateral side, if steps 1 and 2 do not result in a maximal incisal opening (Fig. 5) greater than 35 mm or to the point of dislocation of the unaffected TMJ, (4) lining of the TMJ with a temporalis myofascial flap or the native disc, if it can be salvaged, (5) reconstruction of the ramus condyle unit with either distraction osteogenesis or costochondral graft and rigid fixation, and (6) early mobilization of the jaw. If distraction osteogenesis is used to reconstruct the ramus condyle unit, mobilization begins the day of the operation. In patients who undergo costochondral graft reconstruction, mobilization begins after 10 days of maxillomandibular fixation. Finally (step 7), all patients receive aggressive physiotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Intra-operative photograph showing the gap after resection of ankylotic mass

Fig. 5.

Post-operative photograph showing maximum interincisal opening of the patient

For the follow-up observations lasting from 13 to 31 months, 100% success rate was achieved. Sucess rate is based on increased mobility of the mandible and improved function. The results of this study indicate that the use of temporalis muscle and fascia flap is effective in treating TMJ ankylosis.

References

- 1.Balaji SM. Modified temporalis anchorage in cranio mandibular reankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(5):480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergey DA, Braun TW. The posterior zygomatic arch osteotomy to facilitate temporalis flap placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52(4):426–427. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brusati R, Raffaini M, Sesenna E, Bozetti A. The temporalis muscle flap in temporo-mandibular joint surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990;18(8):352–358. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra P, Dave PK. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;187:449–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chidzonga MM. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis: review of thirty-two cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;37(2):123–126. doi: 10.1054/bjom.1997.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chossegross C, Guyot L, Cheynet F, Blanc JL, Gola R, Bourczak Z, Conrath J. Comparison of different materials for interposition arthroplasty in treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis surgery: long-term follow-up in 25 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;35(3):157–160. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(97)90554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chossegross C, Guyot L, Cheynet F, Blanc JL, Cannoni P. Full-thickness skin graft interposition after temporomandibular joint ankylosis surgery. A study of 31 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(5):330–334. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(99)80075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clauser L, Curioni C, Spanio S. The use of the temporalis muscle flap in facial and craniofacial reconstructive surgery. A review of 182 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1995;23(4):203–214. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Sheikh MM, Medra AM. Management of unilateral temporomandibular ankylosis associated with facial asymmetry. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1997;25(3):109–115. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(97)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faerger TH, Ennis RL, Allen GA. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis following mastoiditis: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(8):866–870. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinberg SE, Larsen PE. The use of a pedicled temporalis muscle-pericranial flap for replacement of the TMJ disc: preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47(2):142–146. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(89)80104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonseca RJ, Walker RV. Oral and maxillofacial trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1991. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guthua SW, Maina DM, Kahugu M. Management of post-traumatic temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children: case report. East Afr Med J. 1995;72(7):471–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habel G, Hensher R. The versatility of the temporalis muscle flap in reconstructive surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;24(2):96–101. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(86)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haidar Z. Ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint: causes and management. J Oral Med. 1986;41(4):246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herbosa EG, Rotskoff KS. Composite temporalis pedicle flap as an inter positional graft in temporomandibular joint arthroplasty: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(10):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90288-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaban LB, Perrott DH, Fisher K. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(11):1145–1151. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90529-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaban LB, Bouchard C, Troulis MJ. A protocol for management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in children. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(9):1966–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karaca C, Baratcu A, Menderes A. Inverted, T-shaped silicone implant for the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Craniofac Surg. 1998;9(6):539–542. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199811000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirk WS, Farrar JH. Early surgical correction of unilateral TMJ ankylosis and improvement in mandibular symmetry with use of an orthodontic functional appliance: a case report. Cranio. 1993;11(4):308–311. doi: 10.1080/08869634.1993.11677983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon TG, Park HS, Kim JB, Shin HI. Staged surgical treatment for temporomandibular joint ankylosis: intraoral distraction after temporalis muscle flap reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64(11):1680–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maki MH, Al-Assaf DA. Surgical management of temporomandibular joint ankylosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19(6):1583–1588. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31818ac12c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manfredini D, Bucci MB, Guarda-Nardini L. Temporomandibular joint bilateral post-traumatic ankylosis: a report of a case treated with inter positional arthroplasty. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(1–2):35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mani V, Panda AK. Versatility of temporalis myofascial flap in maxillofacial reconstruction-analysis of 30 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(4):368–372. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins WD. Report of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint: treatment with a temporalis muscle flap and augmentation genioplasty. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;7(1):125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matukas VJ, Lachner J. The use of autologous auricular cartilage for temporomandibular joint disc replacement: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48(4):348–353. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehrotra D, Pradhan R, Mohammad S, Jaiswara C. Random control trial of dermis-fat graft and interposition of temporalis fascia in the management of temporomandibular ankylosis in children. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46(7):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer RA. The autogenous dermal graft in temporomandibular joint disc surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;46(11):948–954. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okumura M, Kadosawa T, Fujinaga T. Surgical correction of temporomandibular joint ankylosis in two cats. Aust Vet J. 1999;77(1):24–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1999.tb12419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omura S, Fujita K. Modification of the temporalis muscle and fascia flap for the management of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(6):794–795. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(96)90707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paterson AW, Shepherd JP. Fascia lata inter positional arthroplasty in the treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis caused by psoriatic arthritis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;21(3):137–139. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80779-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pogrel MA, Kaban LB. The role of a temporalis fascia and muscle flap in temporomandibular joint surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:14–19. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90173-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raveh J, Vuillemin T, Ladrach K, Sutter F. Temporomandibular joint ankylosis: surgical treatment and long term results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47(9):900–906. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schliephake H, Schmelzesien R, Maschek H, Haese M. Long-term results of the use of silicone sheets after diskectomy in the temporomandibular joint: clinical, radiographic and histopathologic findings. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28(5):323–329. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0020.1999.285280501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wal KG. Dissertations 25 years after the date 7. Temporo mandibular joint ankylosis. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2005;112(10):380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]