Abstract

Objectives

This clinical study was conducted in the department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, at our institute, to study the versatility of temporalis myofascial flap in maxillofacial reconstruction.

Methods

The study group comprised of 20 patients, both male and female patients between the age group of 6 years and 60 years underwent surgery under general anesthesia and temporalis myofascial flap was used for reconstruction of various types of maxillofacial defects including maxillectomy defects arising as a result of ablative surgery for tumors and treatment of aggressive cysts, as an interposing material in TMJ ankylosis surgery and facial reanimation in cases of long standing facial nerve paralysis. Following surgery the cases were evaluated for clinical parameters weekly for first post-operative month followed by monthly review for a minimum period of one and maximum of three years from January 2003 to June 2006.

Results

Temporalis myofascial flap fared well in 16 out of 20 cases (80%), in remaining four cases (20%) three reported back with reankylosis, and in one case of facial reanimation flap breakdown occurred due to infection leading to failure of the procedure.

Conclusion

The temporalis myofascial flap is a versatile option for reconstruction of moderate to large sized maxillofacial defects, the muscle can provide abundant viable and vascular tissue, with minimal to no functional morbidity or esthetic deformity at the donor site.

Keywords: Temporalis myofascial flap, Maxillo-facial

Introduction

Need for viable tissue for reconstruction of maxillofacial defect has been realized centuries ago and research is still on to find a reasonable answer.

The extirpation of major cancer and tumor of head and neck usually results in significant physiologic and somatic changes in the affected organ systems. Resection of oral cavity malignancies and tumor often causes functional disabilities in deglutition and articulation. The aesthetic detriment may also be profound. The head and neck surgeon of today must not only be an oncology expert but also a master architect who can reconstitute and rehabilitate these devastated systems [1].

The use of flaps for reconstruction of defects dates back to 600 B.C. when Sushrutha an Indian ayurvedic hermit used the forehead flap to reconstruct the nose, a technique which is still being used. The credit for using temporalis flap for the first time to reconstruct exenterated orbital defect goes to Golovine 1898. Temporalis myofascial flap holds great promise for the reconstruction of various defect of maxillofacial region either congenital or surgical. The dependable blood supply through middle and deep temporal arteries, proximity to maxillofacial region, possibility to mobilize it to the oral cavity through the under surface of zygomatic arch and its fanned out nature permits the surgeon to use this flap for the reconstruction of various maxillofacial defects and even as an interposing tissue in TMJ surgeries. With refinement of surgery and advancement in techniques, the temporalis myofascial flap (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4), enjoys a wide range of applicability in maxillofacial defects of congenital origin, ablative surgery and facial reanimation [3, 4, 5] (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 1.

Facial and intraoral pre operative view of case 1 ameloblastoma right maxilla

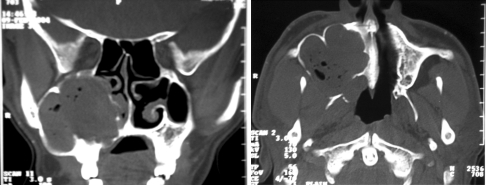

Fig. 2.

Coronal and axial CT scan of case 1 showing the extent of the lesion

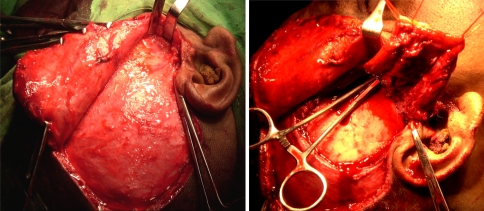

Fig. 3.

Intra-operative view of case 1 showing temporalis myofascial flap being harvested from donor site

Fig. 4.

Post-operative intra oral and facial profile view of case 1 showing the result of the reconstruction using temporalis myofascial flap

Fig. 5.

Pre and 2 year post operative view of case 2, bilateral ankylosis of temporomandibular joint treated with interposition arthroplasty using TMF

Fig. 6.

Pre and post operative view of case 3, congenital long standing facial nerve palsy of right side corrected with temporalis myofascial flap and fascia lata sling

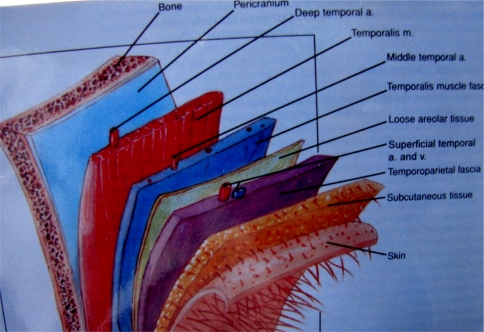

Surgical Anatomy of Temporalis Muscle (Fig. 7)

Fig. 7.

Anatomical layers of tissue in temporal region

The temporalis muscle lies deep to the temporoparietal fascia and is separated from it by a distinct, subaponeurotic plane. It is a fan shaped bipennate muscle that occupies the temporal fossa of the side of the head an area outlined by the superotemporal line and the zygomatic arch. The superficial muscle fibres arise from the periosteum (pericranium) of the temporal fossa and the overlying temporalis fascia. The deep fibre of the temporalis muscle arises from the roof of the infratemporal fossa and the infratemporal crest. The thickness of the muscle varies from 15 mm at the level of zygomatic arch to 5 mm at its peripheral boundaries. The approximate vertical length and the anteroposterior width is 9.9 × 11.6 cm. The thin peripheral muscle fibres converge as they descend inferiorly to form a thick tendon, which passes medial to the arch and inserts onto the anterior border and medial surface of the coronoid process of the mandible, continuing inferiorly and anteriorly to the last molar. The blood supply to the temporalis muscle in man is mainly derived from the anterior and posterior deep temporal arteries (ADTA and PDTA) branches of internal maxillary artery at the infra temporal fossa. Both ADTA and PDTA enter the muscle below the zygomatic arch and deep to the coronoid process. The anterior pedicle is located 1 cm anterior to the coronoid and 2.4 cm inferior to the arch, whereas posterior pedicle is 1.7 cm posterior to the coronoid and 1.1 cm inferior to the arch. Each vessel is on an average 2 cm in length and enters the muscle through its deep surface. There is an additional blood supply derived from middle temporal artery (MTA), a branch of superficial temporal artery [3, 11, 16].

Methods

The study group comprising 20 patients, with various defects in maxillofacial region arising as a result of ablative surgery for tumor, congenital or long standing facial nerve palsy and ankylosis of temporomandibular joint were selected.

The study group comprised of both male and female patients between the age group of 6 and 60 years who underwent surgical reconstruction of various defect in maxillofacial region using temporalis Myofascial flap between the period of January 2003–June 2005. All the surgeries were performed by one surgeon to rule out individual variability in the study. Patients with a history of previous radiotherapy in and around orofacial region, any scar in temporalis muscle region, temporal hollowing, any pathology in temporalis muscle region and patients with any history or presence of infection in or around temporalis muscle region were excluded from the study.

Clinical findings were noted down on a specially designed proforma for all the patients, Cases were reviewed for a minimum follow up period of 1 year and a maximum of 3 years. Suitable radiographs and histopathological examination were made.

Eight patients underwent reconstruction of subtotal maxillectomy defects using TMF flap for various maxillofacial pathology including three cases of squamous cell carcinoma, one case of ameloblastoma, three cases of neurofibroma and 1 case of OKC. of maxilla, Two patients underwent facial reanimation for long standing facial nerve palsy and 10 patients underwent interpositional arthroplasty with TMF interposition for TMJ ankylosis.

All the cases included in the study were evaluated for clinical parameters intra and post operatively such as tension free closure of recipient site accessed by no blanching of tissues at suture sites, complete coverage of defect and no gaping at wound closure site, viability of flap accessed by prick test and color changes, cosmetic deformity over donor site due to temporal hollowing as a result muscle volume loss, scarring and alopecia. The flap was also evaluated for clinical epithelization and healing, flap breakdown, limitation of mandibular range of motion and mouth opening especially in cases of interposition arthroplasty of Temporomandibular joint, the patients were also evaluated for their degree of satisfaction with their speech and mastication and injury to the temporal branch of facial nerve.

Surgical Technique for Reconstruction of Maxillectomy Defect (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4)

A preauricular incision with temporal extension is made, dissection is carried down to the superficial layer of temporalis fascia 2 cm above zygomatic arch, by remaining in this plane the temporal branch of the facial nerve is safeguarded since the nerve runs superficial layer of the superficial layer temporalis fascia. The dissection is then carried between the superficial and deep layers of temporalis fascia down to the zygomatic arch. The deep temporalis fascial attachment was also incised at the superior border of the zygomatic arch; the fascia was incised all around so that it remains attached only to the muscle. Elevation of the muscle along with attached deep temporal fascia was performed in a subperiosteal plane in order to avoid damage to deep temporal arteries which may groove the outer cortex of the temporal bone. The muscle was completely elevated from the temporal fossa and off the infratemporal crest, the muscle remain attached to its vascular pedicle and to the coronoid process. The temporalis muscle was sutured between the pericranium and temporalis fascia at the peripheral margins of the flap, with a blunt dissection, a tunnel was made to the oral cavity superficial to the muscle and deep to the zygomatic arch. With blunt instrument taking care not to crush or tear the muscle and its vascular bundle and using long stay suture, the flap was pushed and pulled down into the oral cavity deep to the zygomatic arch. The muscle was fanned out and sutured into the defect created by subtotal maxillectomy. The temporal region was closed primarily in layers after achieving haemostasis and after placing a suction drain with pressure dressing.

Surgical Technique for Interposition TMJ Arthroplasty

An extended preauricular incision is made; following dissection, a T incision over joint capsule is placed. The bony mass is resected taking care to protect internal maxillary artery, a 1–1.5 cm gap is created between the condylar stump and glenoid fossa. A temporalis muscle flap is developed that includes the overlying temporalis fascia and the underlying pericranium from the most inferior horizontally originated fibres of the temporalis muscle approximately 2 cm in width and about 5 cm in length, at this point with the flap elevated and the pericranium and the temporalis fascia are sewn together to form a muscle sandwich. The flap was then turned down over the arch and into the fossa with pericranium facing towards the glenoid fossa, spread out as an interposing material between the stump and the temporal bone and sutured to remaining soft tissue in the walls of the fossa to seat the flap completely into the fossa passively (Fig. 5).

Surgical Technique for Facial Reanimation

A preauricular incision with temporal extension (hemicoronal) was placed and soft tissue dissection done to expose the temporalis fascia, and a temporalis muscle flap is elevated at the periphery in usual fashion. Simultaneously a fascia lata graft is harvested and sutured to the distal margins of the myofascial flap to increase the total length of the flap. A small incision is placed near the oral commissure in naso-labial fold and blunt dissection is done towards the posterior part of zygomatic arch and temporal region, plane of dissection being superficial to the SMAS (superficial musculo aponeurotic system) layer to avoid damage to existing paralyzed facial nerve considering possible future recovery. The flap with fascia lata extension is then tunneled into the existing channel; the fascia lata at the distal end of the flap is then divided into three sections the upper one is again tunneled and sutured to the upper labial part of orbicularis oris, the middle part is sutured to the oral commissure and the third part is tunneled and sutured to the lower labial part of orbicularis oris muscle (Fig. 6).

Result

Tension Free Closure of the Recipient Site

In the entire 20 study subject group there was no tension on the temporalis myofascial flap when it was sutured to the recipient site intra operatively that is 100% tension free closure of recipient site was achieved.

Necessity for Zygomatic Arch Fracture

Two cases out of 20 subjects (10%) in study group required fracture of the zygomatic arch.

Color of the Flap and Prick Test

All the 8 cases in the maxillectomy reconstruction study group were evaluated for color of the flap on 7th, 15th and 60th day post operatively and prick test was done on the 7th day to assess the viability of the flap. All the 8 cases showed positive prick test with active bleeding over the flap. The color of the flap was assessed in terms of yellow, grey and pink and combination thereof. On 60th post op day 7 out cases appeared pink and one flap showed grayish pink.

Healing and Epithelization

Healing in the immediate post operative period was satisfactory in the entire 20 study subject with no haematoma at donor site. Clinical epithelization in all 8 maxillectomy reconstruction group was satisfactory and occurred in a minimum of 18 and maximum of 24 days period post operatively, with a mean time of 20.37 days. The TMF in 1st week looked edematous bulky and was covered by thick yellowish layer of fascia with varying amount of slough. Between 2nd and 3rd week most edema subsided and flap became less bulky and most of them showed grayish-pink color representing partial epithelization, in 50% of maxillectomy group there was varying amount of sloughing of the covering fascia exposing the granulating muscle bed below. Gradually beginning at the end of 3 weeks and by 6th week all the flaps were epithelized by oral mucosa and pink in color. Prick test was positive for all the cases on 7th day with active bleeding.

Donor Site Morbidity (Scarring, Alopecia and Temporal Hollowing)

Scarring at the site of incision at donor site was insignificant and no alopecia was noted in all 20 study subjects and most of the incision line being masked by the hairline.

Temporal hollowing was noted in seven cases out of 20 study subject (35%).

Mouth Opening (in Millimeter)

Mean of post operative mouth opening for maxillectomy reconstruction and facial reanimation group was 32.37 and 33.0 mm and remained the same in the following post operative years. In cases of TMJ ankylosis (10 cases) with an average (mean) pre operative mouth opening of 5.80 mm, a mean mouth opening of 33.0 mm was achieved on table and in immediate post operative period. Three cases out of 10 cases (30%) reported back with reankylosis at the end of 12, 25 and 36 months respectively. The mean mouth opening of remaining seven cases at the end of 3 years was 29.85 mm.

Breakdown of Temporalis Myofascial Flap

In nine of the cases of maxillectomy and reanimation there was no break down of flap. Flap break down was noted in one of the cases. The case belonged to the facial reanimation group.

Injury to Temporal Branch of Facial Nerve

No permanent paralysis of temporal branch of facial nerve was noted in any of our cases.

Over All Result

In total there was failure of four cases (20%), in three of the cases there was reankylosis and one case of facial reanimation there was flap breakdown with failure of the procedure. The remaining 16 (80%) cases flap fared well and resulted in an overall success of the procedure.

Discussion

It was Golovine (1898) who first reported the use of temporalis myofascial flap for reconstruction of an orbital defect. Recent advancement in technology and techniques has made temporalis myofascial flap a viable and versatile flap for the reconstruction of various defects of the maxillofacial region. The proximity to the maxillofacial region and its attachment to coronoid process and its blood supply from the internal maxillary artery through the deeper surface of the muscle helps its rotation to almost 180º without compromising the viability. Its fan shaped nature and the superficially adherent deep temporal fascia (which act as a protective covering) aids it to be used as a flap facing the oral cavity without any skin graft covering over it [3].

The temporalis muscle is well suited for intraoral reconstruction since it is proximal and adjacent. The muscle is readily accessible through a skin incision that is well hidden in a preauricular crease and in the hair bearing scalp. Because the muscle can be completely separated from all of its attachment except for the neurovascular pedicle, it is highly mobile, and has a wide arch of rotation and transposition. Reconstruction with temporalis muscle produces little functional deficit if the other muscle of mastication remain intact. Trismus has not been a problem [1].

Cancer of the maxilla can be a lethal disease, and its treatment often leaves the patient with marked functional and cosmetic deficits. Many different methods have been proposed for reconstructing these defects, which include a prosthetic obturator, temporalis myofascial flap, infrahyoid myocutaneous flap and pectoralis myocutaneous flap. Myocutaneous free flap with or without osseous component have also been described. The use of obturator work for many cases, but obtaining a proper fit and seal in an edentulous patient is difficult if not impossible. Furthermore resection of such palatal tumor often requires removal of so much hard palate that too little remains to stabilize and support the obturator. Other flaps and free flaps require a second surgical site and associated morbidity [2].

TMJ ankylosis occurs in both children and adults. Early ankylosis in children can be deterrent to normal mandibular growth therefore early diagnosis and early surgical intervention is important. The patients may have difficulty in mouth opening as well as malocclusion; the degree of limitation in mandibular motion varies considerably and depends on the type and amount of tissue connecting the mandible. Management of TMJ ankylosis entails surgical intervention, the need to use an interpositional material to prevent TMJ reankylosis after arthroplasty has been widely discussed. A variety of interposition material have been used including temporalis muscle and fascia, dermis, auricular cartilage, fascia lata, fat, lyodura, silastic and silicone. The most commonly used interposition material at present in temporalis myofascial flap.

Problem that we came across was non-compliance by few of our cases especially the interpositional arthroplasty group resulting into irregular follow up and lack of active jaw physiotherapy which promotes adhesion and organization of haematoma within the joint space, an important factor in the etiology of reankylosis [10, 14].

Temporal hollowing does occur when temporalis muscle is used for reconstruction of large defects but in most of the cases it is not of serious concern as the hollowing defect is camouflaged by hair bearing area of the scalp specially in non-bald and females. Few studies and authors suggest use of allograft like acrylic or silastic to reconstruct the temporal defect. If only anterior part of temporalis muscle is used, the posterior can be repositioned into anterior region to fill the dent [4, 9], since the hollowing is more pronounced in anterior region [3, 8]. In our group of patients it was not a complication of any serious concern to the patient.

Conclusion

The temporalis myofascial flap is classified as type III axial pattern flap, based on two dominant arterial pedicle that is anterior and posterior deep temporal arteries It is because of this dependant vascular supply The temporalis myofascial flap is a versatile option for reconstruction of moderate to large sized maxillofacial defects, the muscle can provide abundant viable and vascular tissue, with minimal to no functional morbidity or esthetic deformity at the donor site.

References

- 1.Koranda FC, Mcmohan MF, Jernstrom VR. The temporalis muscle flap for intra oral reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:740–743. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860070054015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale BJ, Bradford HW. Combined intraoral and lateral temporal approach for palatal malignancies with temporalis muscle reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:531–537. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.5.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mani V, Panda AK. Versatility of temporalis myofascial flap in maxillofacial reconstruction. Analysis of 30 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32:368–372. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su Gwan K. Treatment of temporomandibular joint ankylosis with temporalis muscle and fascia flap. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:189–193. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balaji SM. A modified temporalis transfer in facial reanimation. Int J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2002;31:584–591. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanasono Matthew M, Utley David S, Goode Richard L. The temporalis muscle flap for reconstruction after head and neck oncologic surgery. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1719–1725. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burggasser G, Happak W, Gruber H, Freilinger G. The temporalis blood supply and innervation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;109(6):1862–1869. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abubaker OA, Mustafa B. The temporalis muscle flap in reconstruction of temporal defects; An appraisal of the technique. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:24–30. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.126077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balaji SM. Modified temporalis anchorage in cranio-mandibular reankylosis. Int. J. Oral maxillofacial Surg. 2003;32:480–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards SP, Feinberg Stephen E. The temporalis muscle flap in contemporary oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Oral and Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 2003;15:513–535. doi: 10.1016/S1042-3699(03)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad QG, Siddiqui RA, Khan AH, Sharma SC. Interposition arthroplasty in temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;56(1):5–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02968762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Majumdar A, Baniton R. Suture of temporalis fascia and muscle flaps in temporomandibular joint surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;42:357–359. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong TY, Chung CH, Huang JS, Chen HA. The inverted temporalis muscle flap for intra oral reconstruction: Its rationale and the results of its application. J. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qudah MA, Qudemiat MA, Al-Maaita J. Treatment of TMJ. Ankylosis in Jordanian children- comparison of two surgical techniques. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolka W, Iizuka T. Surgical reconstruction of the maxilla and midface: clinical outcome and factors relating to postoperative complications. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheir D, Lewis B (2002) Hole’s anatomy and physiology. 9th edn. McGraw-Hill company, p 183