Abstract

Purpose

To clinically evaluate the perioperative use of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate for the prevention of alveolar osteitis, to assess the patient compliance to chlorhexidine and to prepare a comprehensive treatment plan to prevent alveolar osteitis after removal of an impacted third molar extraction.

Methods

A prospective study was done on 50 patients with bilaterally impacted lower third molars which were indicated for extraction. Extraction of impacted mandibular third molar on one side was done without using any mouthrinse. While extracting the third molar on the other side, patients were instructed to use chlorhexidine 0.2% mouth rinse for 8 days, 1 day preceding and 7 days following the surgery. They were instructed to use chlorhexidine 0.2% (Rexidine) mouth rinse for 30 s twice a day (before breakfast and after dinner) with 15 ml of the rinse with 1:1 dilution with clean water. All the patients were evaluated for pain, presence or absence of clot and condition of the alveolar bone for the diagnosis of dry socket.

Results

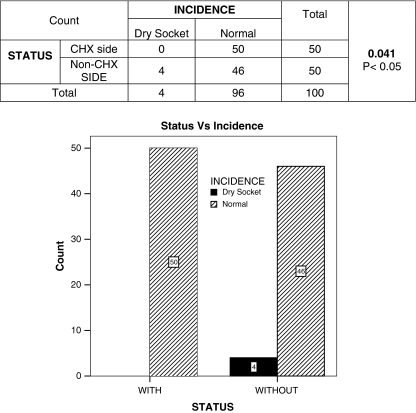

Incidence of dry sockets was 8%, when patients did not use 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate perioperatively which is statistically significant.

Conclusions

It appeared that the incidence of dry socket can be reduced significantly by using 0.2% chlorhexidne gluconate mouth rinse perioperatively (twice daily, 1 day before and 7 days after surgical extraction.

Keywords: Impacted mandibular third molars, Alveolar osteitis, 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate, Mouthrinse

Introduction

Impacted teeth are developmental deformities characteristic of a modern civilization. Third molars are frequently impacted owing to skeletal insufficiency in the area where they normally erupt [1].

Peterson stated, “If impacted teeth are left in the alveolar process, it is highly probable that one or more of a number of problems such as pericoronitis, periodontal diseases, crowding of mandibular incisors, formation of cysts and tumors, root resorption of adjacent teeth, unexplained pain, will result”. To prevent this, impacted teeth should be removed [2].

The ability of operated tissue to heal is an essential part of surgery, providing restitution of tissues following manipulation or removal of pathological entities. When healing fails, either totally or partially, the patient experiences the untoward effects of a surgical complication [1].Osborn and associates reported overall complication rates of third molar surgery as follows: dry socket 6.3%, secondary infection 3.7%, dysesthesia 0.6%, bleeding 0.2% [3]. Dry socket is an annoying post extraction event which has been known by variety of names [1]. IR BLUM defined dry socket or alveolar osteitis as postoperative pain in and around the extraction site, which increases in severity at any time between 1 and 3 days after the extraction accompanied by a partially or totally disintegrated blood clot within the alveolar socket with or without halitosis [4].

The predisposing factors or conditions which were considered in formation of dry socket are insufficient blood supply to the alveolus, infection provoked during or after the extraction, excessive irrigation and curettage of the alveolus after extraction, heavy sucking or spitting post operatively, trauma to the alveolar bone during extraction. However, fibrinolysis, as a result of bacterial invasion with subsequent loss of blood clot is believed to be the general cause of the dry socket [5, 6].

References in the literature correlating to the prevention of dry socket can be divided into non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological methods include a comprehensive history of the patient with identification, and if possible, elimination of risk factors associated with increased risk to develop dry socket. The pharmacological prophylactic interventions are related to one or more of the following groups: antibacterial agents, antiseptic agents and lavage, antifibrinolytic agents, steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, obtundent dressings and clot support agents [4].

The primary role of bacteria in the process of fibrinolysis has been documented; the most effective method for reducing alveolar osteitis has been through the use of agents that systemically or topically reduce the oral microbes in the wound. Oral rinsing with chlorhexidine has shown to reduce the quantity of oral microbial population [7].Chlorhexidine is a bisdiguanide antiseptic with antimicrobial properties. Presurgical and post-surgical oral rinsing with 0.2% chlorhexidine have been reported to yield 45–80% reduction in alveolar osteitis rates [6].

This study has been undertaken to clinically evaluate the efficacy and safety of perioperative use of 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthrinse in prevention of dry socket.

Materials and Methods

This in vivo study was carried out on 50 patients who reported to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, with bilaterally symmetrical impacted mandibular third molars requiring surgical extraction Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

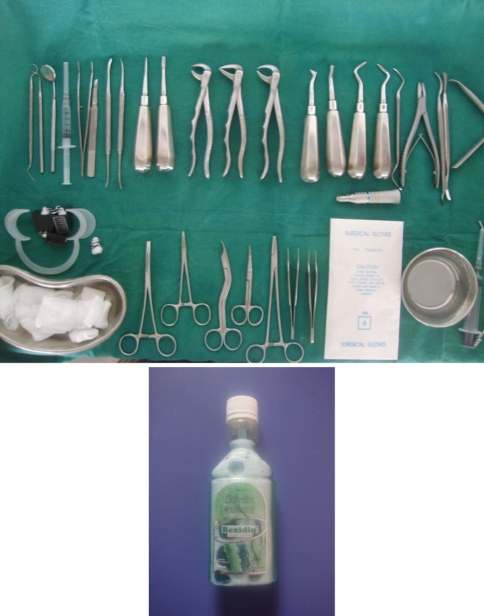

Fig. 1.

Armamentarium

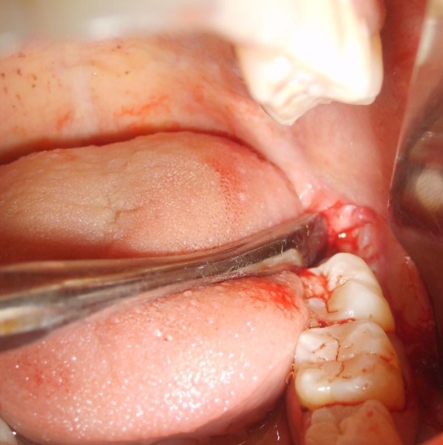

Fig. 2.

Incision

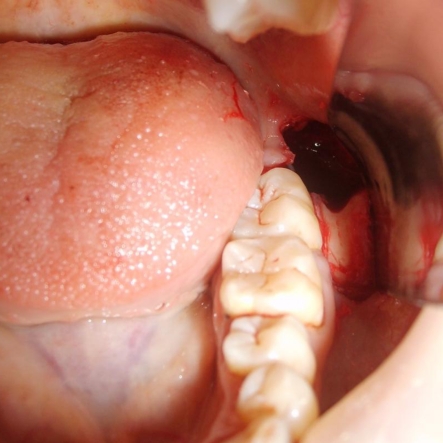

Fig. 3.

Reflection of the flap

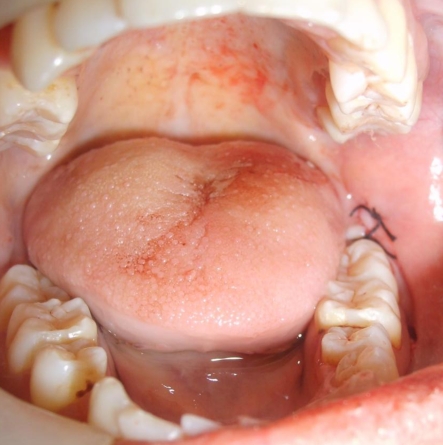

Fig. 4.

Guttering of the bone

Fig. 5.

Extraction socket

The criteria for selection of patients were as follows:

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with bilaterally symmetrical impacted mandibular third molars indicated for extraction.

Patients above 18 years of age.

Patients who were willing for follow up.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients on antibiotic prophylaxis.

Patients known to be allergic to chlorhexidine.

Patients who are smokers.

Patients with systemic disorders.

Patients who are on oral contraceptives.

All the patients were informed regarding the study and informed consent was obtained. Preoperative investigations were carried out for all the patients and thorough oral prophylaxis was done prior to surgical procedure. All the procedures were carried out by the same operator using standard surgical technique.

Surgical Technique Followed for the Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Third Molar

The face was painted with povidone iodine solution and standard draping was done using sterile drapes. Intra oral preparation was done with povidone iodine solution. Anesthesia was secured with 2% lignocaine hydrochloride with 1:80,000 adrenaline through inferior alveolar nerve block, lingual nerve block and long buccal nerve block.

A standard Terrance ward incision was placed and the mucoperiosteal flap was reflected to expose the site of the impacted tooth. Bone removal was carried out, using round bur by guttering technique. Odontotomy was performed whenever necessary to facilitate tooth removal. After an adequate amount of bone was removed, the tooth was delivered from the socket by using elevator. Sharp bony edges were smoothened with bone file and socket was irrigated with povidone iodine and saline to remove bone debris. Complete hemostasis was achieved before wound closure. Wound was closed with 3–0 silk suture using interrupted suture technique and the patient was given postoperative instructions. Patients were advised to take diclofenac sodium 50 mg tablets, 8th hourly for 3 days postoperatively.

Extraction of impacted mandibular third molar on one side was done without using any mouthrinse. While extracting the third molar on the other side, patients were instructed to use 0.2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse for 8 days, 1 day preceding and 7 days following the surgery, except on the day of surgery in order to avoid clot dislodgement. They were instructed to use chlorhexidine 0.2% (Rexidin) mouth rinse for 30 s twice a day with 15 ml of the rinse with 1:1 dilution with clean water.

The patients were examined on 3rd and 5th post operative day on both sides for:

Pain–Pain was recorded objectively using VAS (visual analogue scale). The end points of the scale were no pain and severe pain.

The values on scale were categorized as:

No pain (0–1)

Mild (1–3)

Moderate (3–6)

Severe (6–10)

Presence or absence of clot—extraction socket was examined for blood clot clinically and recorded as present or absent.

Alveolar bone—extraction socket was examined clinically and recorded as covered or uncovered.

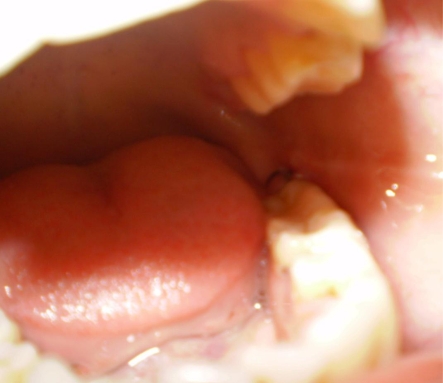

The diagnostic criteria were chosen according to previous studies [4, 8].The data thus obtained was tabulated and subjected to statistical analysis Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Fig. 6.

Closure of the wound

Fig. 7.

Third post-operative day

Fig. 8.

Fifth post-operative day

Fig. 9.

After suture removal

Fig. 10.

Dry socket

Results

This study was carried out on 50 patients with bilaterally symmetrical impacted mandibular third molars reported to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, requiring surgical extraction of impacted mandibular third molars of both sides.

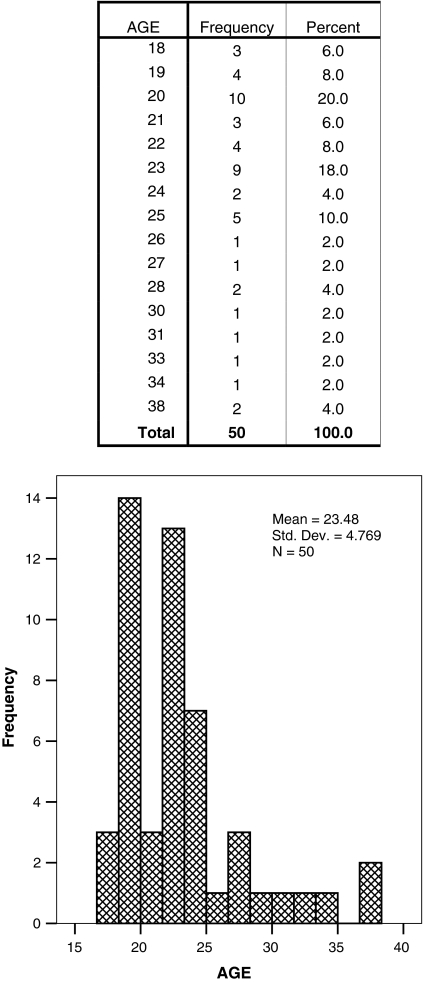

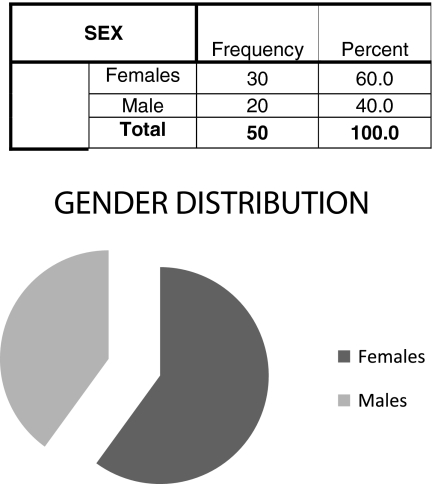

Table 1 shows data of 50 patients. Mean age of patients in years is 23.48. Table 2 shows gender distribution included 20 females and 30 males.

Table 1.

Age distribution

Table 2.

Gender distribution

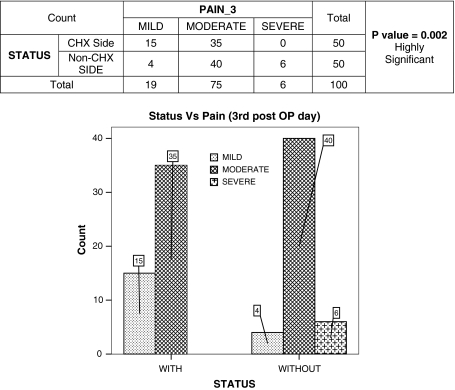

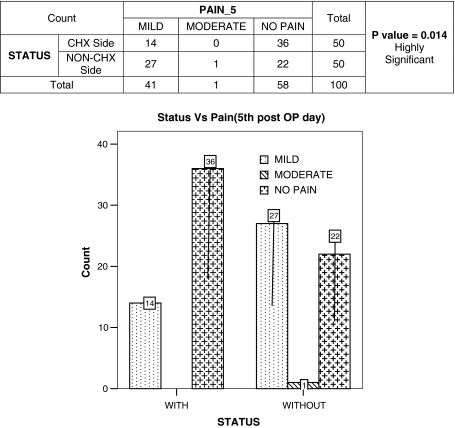

Tables 3 and 4 describes the pain 3rd and 5th post operative in CHX side and non CHX side and a statistically significant difference was found on both 3rd and 5th day between both sides. Pain was severe in 12% of surgical sites in non-CHX side on 3rd day as compared to 0% in the CHX side. Pain was moderate and mild in 2% and 54% of surgical sites respectively on non-CHX side on 5th day whereas no case experienced moderate or severe pain in CHX side.

Table 3.

Pain (3rd post operative day)

Table 4.

Pain (5th post operative day)

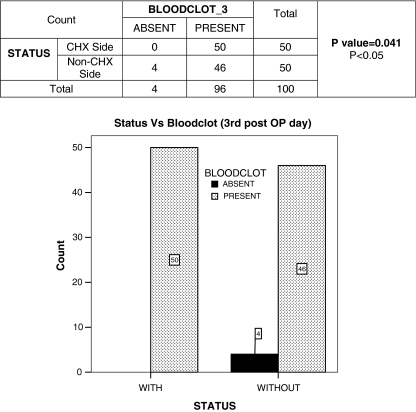

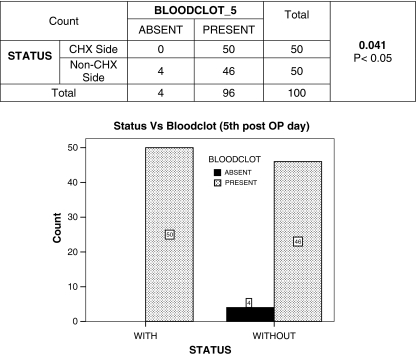

Tables 5 and 6 describes the presence or absence of blood clot in extraction socket on 3rd and 5th postoperative day in CHX side and non-CHX side. A statistically significant difference was found between two sides on both 3rd and 5th day. Blood clot was found to be present in 100% of surgical sites in CHX side on 3rd and 5th day whereas it is present in 92% of surgical sites in non-CHX sides.

Table 5.

Blood clot (3rd post operative day)

Table 6.

Blood clot (5th post operative day)

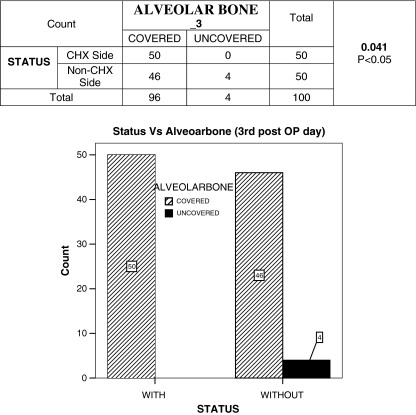

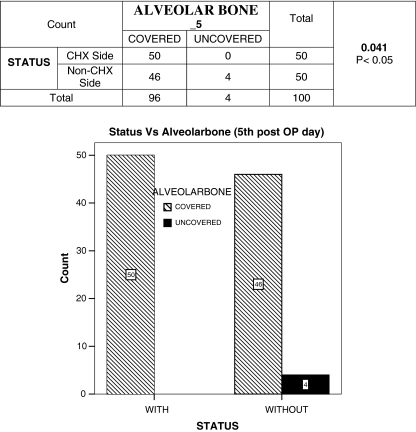

Tables 7 and 8 describes the covering of alveolar bone in extraction socket on 3rd and 5th postoperative day in CHX side and non-CHX side. A statistically significant difference was found between two sides on both 3rd and 5th day. Alveolar bone was found to be covered in 100% of surgical sites in CHX side on 3rd and 5th day whereas it was found to be covered in 92% of surgical sites in non-CHX sides.

Table 7.

Alveolar bone (3rd post operative day)

Table 8.

Alveolar bone (5th post operative day)

Table 9 show the incidence of dry sockets. 4(8%) dry sockets occurred in non-CHX side whereas no dry sockets occurred in CHX side.

Table 9.

Incidence of dry sockets

Table 10 shows incidence of dry sockets according to type of impaction in which two dry sockets occurred in distoangular impactions and two dry sockets occurred in horizontal impactions.

Table 10.

Incidence of dry sockets according to type of impaction

| Type of impaction | Incidence of dry socket |

|---|---|

| Distoangular | 2 |

| Horizontal | 2 |

| Mesioangular | 0 |

| Vertical | 0 |

| Total | 4 |

Table 11 shows the incidence of dry sockets according to gender in which two dry sockets were found in males and two dry sockets were found in females.

Table 11.

Incidence of dry sockets according to gender

| Sex | Incidence of dry socket |

|---|---|

| M | 2 |

| F | 2 |

| Total | 4 |

Discussion

Crawford [3] first described the term dry socket which is characterized by heavy pain of neuralgic character 2–3 days after the removal of the tooth, disintegration of normal blood clot and empty alveolus. Like other diseases for which etiopathogenesis have not been determined, this disease has also acquired numerous names like alveolar osteitis, fibrinolytic alveolitis, alveolitis sicca dolorosa, avascular socket, dolor post extraction, epithelialized socket, leeren alveole, necrotic alveolar socket, painful socket, alveolitis, circumscribed osteitic foci, localized alveolitis, osteitis post extraction, localized acute alveolar osteomyelitis, post exodontic alveolar osteitis and post extraction osteomyelitic syndrome [4].

The reported incidence of alveolar osteitis (dry socket) following third molar extractions ranges from 1 to 30% [5]. Most of the variation in the incidence is most likely a result of the definition of the syndrome [1].

Birn [5] divided the etiological factors of dry socket into two main groups.

General factors

Local factors

General factors include patients with heart diseases, uncontrolled diabetes, liver diseases, syphilis, anemia, hemorrhagic diathesis, disturbance in the function of the endocrine glands, diseases of sympathetic nervous system and patients with nutritional disturbances such as vitamin A, B, C and D deficiencies and calcium or phosphorous deficiencies. He concluded that these factors are decisive in only few cases.

Local factors include,

Insufficient blood supply to the alveolus.

Trauma to the alveolar bone during extraction.

Infection during or after the extraction.

Increased fibrinolytic or proteolytic activity in the blood clot.

The author also explained the pathogenesis of the dry socket in which he states that infection of the extraction wound during or immediately after the extraction and trauma, cause inflammation of the marrow spaces of the alveolar bone which gives rise to liberation of tissue activator that convert plasminogen in the blood clot to plasmin. This dissolves the blood clot and at the same time releases kinins from kininogen, which is also present in the clot. The final result will be dissolution of the blood clot and violent pain. Goldstein et al. [9] have shown that bacterial endotoxins are able to release fibrinolytic activity from human leucocytes. Thus, in addition to the liberated tissue activators from the normal cells of the marrow spaces there is a possibility of further fibrinolytic activity originating from the cells linked up with the inflammation.

Nitzan explained the role of microbial inhabitants of the oral cavity, belonging specifically to the genus Treponema, and their possible role in causing premature clot lysis [10, 11]. The reduction of normal oral flora before oral surgery has been shown to decrease post extraction symptoms [12, 13]. Consistent with the strongly suspected microbial pathogenesis of dry socket, a variety of antibacterial therapeutic modalities have been studied in clinical trials to determine an acceptable preventive routine use after extraction [14–17]. Of particular interest is the past use of CHX as an antimicrobial mouthrinse.

CHX digluconate (a poly biguanide) is water soluble and readily dissociates, releasing the positively charged CHX at physiologic pH. The bacteriocidal effect of the drug is due to cationic molecular binding to extramicrobial complexes and negatively charged microbial cell walls. This has a net effect of altering the osmotic equilibrium of the cell, resulting in electrolyte loss followed by cell lysis [9, 18, 19].

In 1997 Legarth [20] studied the effect of 0.2% chlorhexidine on dry socket prevention and noted a 45% decrease in a group of 60 patients. Similar to this in our study, there was 100% reduction in a group of 50 patients.

Tjernberg [21] in his study found that only one patient in a test group of 30 using 0.2% chlorhexidine rinse perioperatively had alveolar osteitis as opposed to 5 of 30 patients in the control group which is statistically significant. In our study, we found that four patients had alveolar osteitis in a group of 50 in the control group, where as in test group there was no incidence of alveolar osteitis which is also significant.

Hermesch et al. [6] conducted a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, parallel group study among 279 subjects, in which 0.12% chlorhexidine was used perioperatively (7 days before and 7 days after the surgical extractions).There was a statistically significant reduction in the incidence of alveolar osteitis similar to our study wherein, among 50 subjects who used 0.2% chlorhexidine rinse perioperatively (1 day before and 7 days after the surgical extractions) there was no incidence of alveolar osteitis, which is statistically significant.

Larson [7] conducted a prospective randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study with 139 patients (278 bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars), wherein there was a 60% reduction in the incidence of alveolar osteitis reduction rates after the perioperative use (7 days before and 7 days after the surgical extractions) of 0.12% of chlorhexidine mouth rinse. It supports our study, in which there was 100% reduction in the incidence of alveolar osteitis in a group of 50 patients.

Fredric L Bonine [22] conducted a nonrandomized prospective study over a three year period, 371 patients received either no treatment (group 1), 2 weeks of twice daily chlorhexidine rinse postsurgery (group 2), or one rinse presurgery (group 3) and found 60% reduction in group 2. But in our study patients used 0.2% CHX mouth rinse twice daily for 7 days before surgery and 7 days after surgery and we found 100% reduction in the incidence of alveolar osteitis which is statistically significant (P = 0.041).

The results of our study showed that the incidence of dry sockets were higher in patients when they did not use 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash than, when they used 0.2% chlorhexidine perioperatively (twice daily, 1 day before and 7 days after the surgical extractions). An interesting finding in our study was that, no case of dry socket was seen in patients, when they used 0.2% CHX perioperatively. The statistically significant difference was found in the incidence of dry sockets. All the 50 patients used 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinse with no complaints of any adverse reactions or discomfort. So, it is advantageous to advice patients to use 0.2% CHX perioperatively (twice daily, 1 day before and 7 days after the surgical extractions) for the prevention of alveolar osteitis.

References

- 1.Helfrick JF, Alling CC III (2009) Impacted teeth. 1st edn. Thieme Medical Publishers, New York

- 2.Peterson LJ. Principles of management of impacted teeth. In: Peterson LJ, Ellis E III, Hupp JR, Tucker MR, editors. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery. St Louis: CV Mosby Co; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osborn TP, et al. A prospective study of complications related to mandibular third molar surgery. J Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. 1985;43:767. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blum IR. Contemporary views on dry socket (alveolar osteitis). A clinical appraisal of the standardization, etiopathogenesis and management: a critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:309–317. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birn H. Etiology and pathogenesis of fibrinolytic alveolitis. Int J. Oral Maxillofac Surgery. 1973;2:211–263. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charles B, Hermesch, et al. Perioperative use of 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate for the prevention of alveolar osteitis. Efficacy and risk factor analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral PatholOral RadiolEndod. 1998;85:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson PE. The effect of chlorhexidine rinse on the incidence of alveolar osteitis following the surgical removal of mandibular third molar. J of Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:932–937. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90055-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altonen M, Saxen L, Kosunen T, Ainamo J. Effect of two antimicrobial rinses and oral prophylaxis on preoperative degerming of saliva. Int J Oral Surg. 1976;5:276–284. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(76)80028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein G, Berman C, Jaffen R. Chlorhexidine an adjunct to periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1986;57:370–377. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.6.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitzan DW. On the genesis of “dry sockets”. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:706–710. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nitzan DW, Sperry JF, Wilkins TD. Fibrinolytic activity of oral anaerobic bacteria. Arch Oral Biol. 1978;23:465–470. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(78)90078-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown LR, Merrill SS, Allen RE. Microbiologic study of intraoral wounds. J Oral Surg. 1970;28:89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mac Gregor AJ, Hart P. Bacteria of extraction wound. J Oral Surg. 1970;28:885–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scully JR (1980) Influence of polylactic acid, mesh on the incidence of localized alveolitis. Master’s thesis, University of Iowa, Iowa city

- 15.Boyne PJ, Kruger GO. Topical implantation of topical oxytetracycline cones in the extraction sockets. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;64:224–235. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall HD, Bildman BS, Hand CD. Prevention of dry socket with local application of tetracycline. J Oral Surg. 1971;29:35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jokinen MA. Prevention of postextraction bacterimia by local prophylaxis. Int J Oral Surg. 1978;7:450–452. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(78)80036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonesvoll P. Oral pharmacology of chlorhexidine. J Periodont Res. 1977;12:49–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1977.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hugo WB, Longworth AR. Some aspects of the three mode of action of chlorhexidine. J Pharmcol. 1964;16:655–662. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1964.tb07384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legarth J. Effect of chlorhexidine on the development of dry socket. Oral surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;59:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tjernberg A. Influence of oral hygiene measures on the development of alveolitis sicca dolorosa after surgical removal of mandibular third molars. Int J Oral Surg. 1979;8:430–434. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(79)80081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredric L Bonine (1995) Effect of chlorhexidine rinse on the incidence of dry socket in impacted mandibular third molar extraction sites . Oral surg Oral med Oral pathol Oral Radiol Endol 79:154–158 [DOI] [PubMed]