Abstract

Juvenile Ossifying Fibroma (JOF) is an uncommon fibro-osseous lesion affecting the facial bones. Although a benign entity, JOF is known to be locally aggressive and has a high tendency to recur. Two distinctive microscopic patterns have been described; a trabecular variant and a Psammomatoid variant. The latter variant is predominantly a craniofacial lesion and occurs rarely in the jaws. We report a rare case of Psammomatoid Juvenile ossifying fibroma that occurred in maxilla of a 20 year old female patient.

Keywords: Maxilla, Psammomatoid ossifying fibroma, Psammoma bodies

Introduction

Juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) also known as Juvenile Active Ossifying Fibroma and juvenile aggressive ossifying fibroma is a benign bone-forming neoplasm and it is defined as a variant of the ossifying fibroma in the craniofacial skeleton of juvenile patients [1, 2]. Juvenile Ossifying fibroma is a broad term to describe two distinct histopathological variants as identified in a recent study by Samik El-Mofty [2]: Psammomatoid Juvenile Ossifying fibroma (PsJOF) is characterised by the presence of small uniform spherical ossicles that resemble Psammoma bodies and Trabecular Juvenile Ossifying fibroma which is distinguished by the presence of trabeculae of fibrillar osteoid and woven bone. Benjamins [3] in 1938 first reported PsJOF, who called the lesion “osteoid fibroma with atypical ossification of the frontal sinus”. Later, in 1949 Golg [4] reported two cases of what he called “Psammomatoid ossifying fibroma of the nose and paranasal sinuses”. The term “Juvenile active ossifying fibroma” was given by Johnson [5] in 1952 describing it as a cellular mass which generates innumerable small uniform sized osteoid bodies. Makek [6] categorized these lesions as Psammous desmo-osteoblastomas. Margo [7], in 1985 described PsJOF as a distinctive solitary fibro-osseous lesion of young individuals that affects the orbit and shows distinguishing histologic features.

Significant demographic difference between the two variants of Juvenile Ossifying fibroma were noted by Samik El Mofty [2] while the trabecular variant is predominantly a gnathic lesion, with a predilection for the maxilla, PsJOF occurs more commonly in the sinonasal and orbital bones. Johnson et al. [5] and Makek [6] in their case series reports also found that 70% of the PsJoF’s occurred in the paranasal sinuses, 20% in the maxilla and only about 10% in the mandible.

The two categories also have a distinct predilection for specific age groups: the average age of occurrence of TrJOF is 8 1/2–12 year, only 20% of the patients are over 15 years of age whereas that of PsJOF is 16–33 years although in some reports patients’ age ranged from 3 months to 72 years [2].

JOF tends to occur at younger age group and is locally aggressive and these characteristics make them different from conventional ossifying fibroma and other fibro-osseous lesions [1, 2]. Moreover, JOF may clinically manifest with rapid painless expansion of the affected bone as an aggressive lesion mimicking malignancy such as osteosarcoma [8]. So, it is important to accurately recognize JOF for reaching the diagnosis and treatment planning.

The incidence of JOF is still unknown because of relatively few cases reported till date. We report a rare case of juvenile Psammomatoid ossifying fibroma of maxilla in a 20 yr old female.

Case Report

The patient, a 20 year old female presented to our ENT OPD with a complaint of swelling on the right side of her face. The swelling started as a small lump some 3 years back with a rapid increase from last 6 months leading to obvious bulge on face, blockage of his nose and loss of teeth (Fig. 1). There was no history of pain, toothache, discharge of pus or parasthesia, restriction of ocular movements, pain on ocular movements and decrease in vision. On extraoral examination and palpation the swelling was firm and non tender of about 7 cm × 10 cm in size extending from infraorbital margin to gingivobuccal sulcus. On oral examination swelling was non tender with intact mucosa, did not bleed on touch, firm in consistency with loss and loosening of tooth. It involved whole of right maxilla causing a bulge in the right half of the hard palate. It extended from junction of soft palate and hard palate to gingivobuccal sulcus with obliteration of gingivobuccal sulcus (Fig. 2). Anterior rhinoscopy showed mass in the right nasal cavity obliterating it.

Fig. 1.

Swelling right half of face

Fig. 2.

Intraoral swelling causing bulge in hard and soft palate

Plain X-rays of the face were not done as they don’t provide sufficient information as compared to CECT. CECT Scan (Fig. 3) of the skull was done which showed a lobulated, expansile lytic lesion of size 7 cm × 6cm × 14 cm with CT attenuation value of 40–60 HU seen arising from right maxillary bone with compression and deformation of right infraorbital wall, nasal fossa, right alveolar margin, hard palate and soft palate with no evidence of any haemorrhage, calcification or septa formation. A Provisional diagnosis of juveline ossifying fibroma was made.

Fig. 3.

Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) Scan showing mass arising from right maxilla

The FNAC of the lesion showed degenerated cells and osteoid like material in a haemorrhagic background. Preoperative incisional biopsy was done which showed that tumour lacked malignant cells but no definitive diagnosis could be made.

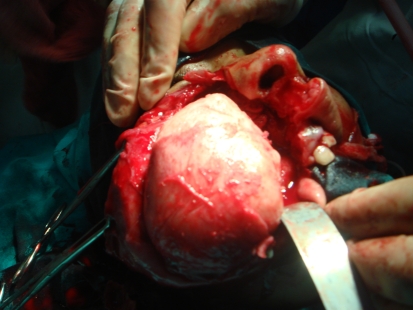

Total maxillectomy was done (Fig. 4) and it was observed that whole of the maxilla was turned into a mass and inferior orbital wall was deformed but intact. Periosteum and orbital contents were preserved. Cavity was lined by split thickness skin graft. Obturator was placed intraoperatively in the cavity of maxillectomy and removed after 5 days. Patient on first week after surgery (Fig. 5) had healed facial incision. A transient obturator with artificial denture was placed in the cavity with the support of the remaining teeth after 3 weeks of surgery. Patient did not till now turn up for a permanent obturator.

Fig. 4.

Operative picture showing maxillary mass

Fig. 5.

Picture showing healed incision at first week after surgery

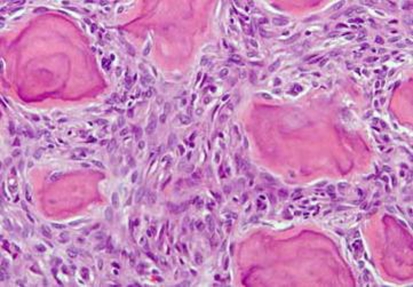

Maxillectomy specimen was sent to histopathology which showed cellular stroma with spindle shaped cells arranged in Strands and whorls and small psammoma-like bodies (Fig. 6). Irregular strands of osteoid matrix rimmed with plump osteoblasts were scattered in the connective tissue stroma. Areas of haemorrhage were also evident in the stroma and diagnosis of psammomatoid juveline ossifying fibroma was made.

Fig. 6.

Microscopic picture on Haematoxylin and Eosin staining (40×) shows cellular stroma with small psammoma—like bodies

Discussion

The fibro-osseous lesions are thought to be the result of diverse processes in which the normal bony architecture is replaced by fibroblasts and collagen fibers that contain variable amounts of mineralized material [9]. The spectrum of fibro-osseous lesions includes a variety of developmental, reactive or dysplastic lesions and neoplastic entities like OF, JOF, FD and so on [9].

Juvenile Ossifying fibromas (JOF) are benign, potentially aggressive fibro osseous lesions of the craniofacial bones. JOF needs to be distinguished from malignant bone tumours in that there is a similarity of clinical manifestations, but JOF can be easily excluded from malignant bone tumours on the routine histological examination [1]. Additionally, it may be difficult to distinguish JOF from other fibro-osseous lesions because of the overlapping features.

TrJOF also known as trabecular desmo-osteoblastoma is defined as a lesion affecting the jaws of children composed of a cell rich fibrous stroma containing bundles of cellular osteoid and bone trabeculae without osteoblastic rimming, and aggregates of giant cells [2]. The great majority of the patients are children and adolescents. Males and females are equally affected. The maxilla and the mandible are the dominant sites of incidence. Occurrence in the maxilla is slightly more frequent than in the mandible [2].

PsJOF is a unique variant of JOF that has a predilection for the sinonasal tract and the orbit particularly centered on the periorbital, frontal, and ethmoid bones [2]. The lesion has demonstrated a potential to proliferate, invade and destroy tissues untill the eyes and the cerebrospinal space are affected [10]. In addition to its aggressive behaviour this lesion also has a very strong tendency to recur and recurrence rate as high as 30–56% have been reported [5–7]. In general, patients with PsJOF are a few years older than those with TrJOF.

Gender predilection has been a matter of controversy with some authors claiming predilection for either sex whereas Johnson et al. found higher incidence [5] in females and El Mofty [2] reported a male predilection.

One clinical feature that helps to differentiate TrJOF from PsJOF, is the site of involvement with PsJOF occurring mainly in the paranasal sinuses and TrJOF occurring mainly in maxilla. Mandibular and extracranial involvement is rare. The greatest majority of the reported cases of PsJOF originated in the paranasal sinuses, particularly frontal and ethmoids but as seen in our rare case it originated from maxillary sinus. Sohyung Park in a study found 6 cases of Ps JOF out of which only one occurred in maxilla. About 10% have been reported in the calvarium. Makek [6] in his review indicated that 7% of the cases occurred in the mandible. In a more recent Samik El-Mofty [2] study one of three cases originated in the mandibular ramus.

The pathogenesis of PsJOF jaw lesions are related to the maldevelopment of basal generative mechanism that is essential for root formation. The developing tooth can either be displaced, missing or remain unerupted [5]. The pathgnomonic feature of this fibro-osseous lesion is the presence of eosinophilic spherical structures dispersed in a fibrous stroma consisting of uniform, stellate, and spindle shaped cells that are arranged as strands and whorls. Golg [4] was the first to term these unique spherical structure as Psammoma-Like bodies. These particles vary in appearance, but usually have a central basophilic area and a peripheral eosinophilic fringe [11]. Ultrastructurally, Psammoma–like bodies in PsJOF were found to possess a dark rim of crystals from which small spicules and needle like crystalloids project toward the periphery [12]. Cystic degeneration and aneurysmal bone cyst formation has been reported in some cases.

PsJOF is clinically manifested as bone expansion that may involve the orbital or the nasal bones and sinuses. Orbital extension of sinonasal tumors may result in proptosis, and visual complaints including blindness, nasal obstruction, ptosis, papilledema, and disturbances in ocular mobility [13].

Radiographic examination shows a round, well-defined, sometimes corticated osteolytic lesion with a cystic appearance as seen in our case. Sclerotic changes are evident in the lesion which may show a ground-glass appearance. In computed tomographic scans set on bone window, the lesions appear less dense than normal bone. The lesions may range in size from 2 to 8 cm in diameter as also seen in our case. PsJOF may appear multiloculated on CT scans. Areas of low CT density may be noted due to cystic changes [13].

On gross examination, the tumor is described as yellowish, white and gritty [12] as seen in our case.

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, No malignant change has been observed [13].

Conclusion

Psammomatoid Juvenile ossifying fibromas are unique lesions that occur commonly in children. These are unique because of their aggressive behaviour mimicking malignancy. These lesions occur rarely in maxilla. Psammoma-Like bodies are the hallmark of this neoplasm. Clinical, radiographic and histopathological correlation will be beneficial in arriving at the accurate diagnosis

References

- 1.Brannon RB, Fowler CB. Benign fibro-osseous lesions: a review of current concepts. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:126–143. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200105000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Mofty (2002) Psammamatoid and trabecular juveline ossifying fibroma of trabecular juveline ossifying fibroma of the craniofacial skeleton:Two distinct clinicopathological entities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path Oral Radiol Endod 93:296–304 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Benjamins CE. Das Osteoid Fibroma mit atypischer verkalkung im sinus frontalis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1938;26:26–43. doi: 10.3109/00016483809118422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golg H. Das Psammoma Osteoid fibroma der nase und ihrer Nebenhohlen. Monatsschr Ohrenheilkd Laryngorhinol. 1949;83:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson LC, Yousefi M, Vinh TN, Heffner DK, Hymans VJ, Hartman KS (1991) Juvenile active ossifying fibroma, its nature, dynamics and origin. Acta Otolaryngol 488(suppl 1):1–40 [PubMed]

- 6.Makek M (1983) Clinical pathology of fibro-osteo-cemental lesions of the cranio-facial and jaws bones—a new approach to differential diagnosis. S. Karger. Basel, New york, p 128

- 7.Margo CE, Ragsdale BD, Perman KI, Zimmerman LE, Sweet DE. Psammomatoid (juvenile) ossifying fibroma of the orbit. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:150–159. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinaggio J, Land M, Cleveland DB. Juvenile ossifying fibroma of the mandible. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:648–650. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2003.50145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su L, Weathers DR, Waldron CA. Distinguishing features of focalcemento-osseous dysplasia and cemento-ossifying fibromas: I apathologic spectrum of 316 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:301. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park S, Lee B-J, Le JH, Cho K-J (2007) Juvenile Ossifying Fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 8 cases and comparison with craniofacial fibro-osseous lesions. Korean J Pathol 41:373–379

- 11.Weing BM, Vinh TN, Smirnitopoulous JG, Fowler CB, Houston GD, Heffner DK (1995) Aggressive Psammomatoid ossifying fibromas of the sinonasal region—a clinicopathological study of a distinct group of Fibro-Osseous Lesions Cancer 76:1155–1165 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Damjanov I, Maenza RM, Synder GC, III, Ruiz JW, Toomey JM. Juvenile ossifying Fibroma: ultra structural study. Cancer. 1978;42:2668–2674. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197812)42:6<2668::AID-CNCR2820420623>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eversole R, Su L, ElMofty S. Benign fibro-osseous lesions of the craniofacial complex: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:177–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]