The relationship between the serum uric acid (SUA) and gout, hypertension and obesity has been known since the late 19th century. After 1960s many epidemiological studies confirm the relationship between the SUA level and various cardiovascular diseases, such as arterial hypertension, atherosclerosis, stroke, acute and chronic heart failure. This relationship is observed not only in frank hyperuricemia (defined by SUA > 7 mg in men and > 6 mg in women), but also in the high – normal values of SUA (defined by SUA > 5.5 mg/dl) (1, 2). The significance of this association is still unknown and in literature there are controversies concerning the significance of hyperuricemia in cardiovascular disease.

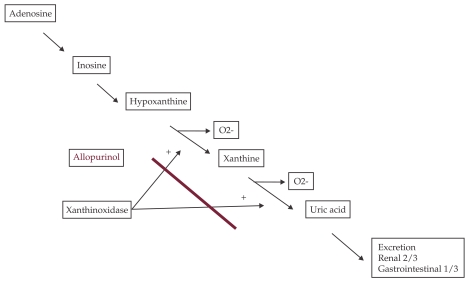

Uric acid is the final oxidation product of purine catabolism in humans and in higher primates. The last metabolic step, the conversion of hypoxanthine to uric acid is regulated by the enzyme xanthine oxidoreductase (XO). The major sources of XO are the liver and the small intestine, but there are evidences for local production of XO by the endothelium and the myocardium. As a part of this process reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced (Figure 1). XO activity is up-regulated in many cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial ischemia, reperfusion injury, left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction and heart failure and is associated with enhanced oxidative stress.

Figure 1.

Uric acid synthesis: In humans uric acid is the terminal step of purine methabolism, catalyzed by xanthinoxidase, which also produces superoxide. Xanthinoxidase is inhibited by allopurinol

Hyperuricaemia is a very common metabolic disorder. Elevated SUA levels occur in 2–18% of the population, varying in relationship to age, sex, and many other factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Most common features of trisomy 13 (the clinical signs that make up the classical triad for the recognition of Patau syndrome are marked in the table)

| Group | Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Postmenopausal women | Estrogen is uricosuric |

| African Americans | Unknown |

| Renal disease | Decrease in GFR increases SUA levels |

| Diuretics | Volume contraction promotes SUA reabsorption |

| Hypertension | Urate ressertions increased in setting and is tightly linked to SUA reabsorption; microvascular disease predisposes to tissue ischemia that leads to increased urate generation (from adenosine breakdown) and reduced excretion (due to lactate competing with urate transporter in the proximal tubule); some hyperuricemic hypertension may be due to alcohol ingestion or lead intoxication |

| Alcohol use | Increases SUA generation, decreases SUA excretion |

The SUA level reflects the net balance between its constant production and excretion. Dietary intake of urate provides a source of uric acid precursors. To maintain homeostasis, SUA is eliminated by the kidney and the gastrointestinal tract. Two thirds of the daily turnover of the urate is excreted by the kidney, where it is completely filtered at the glomerulus, completely reabsorbed in the proximal tubule, then secreted (aprox 50% of the filtered load), and finally reabsorbed.

The high SUA level can be due to an excessive production or to a decreased excretion. An increased dietary purine or fructose intake increases the SUA production. The SUA level is higher in postmenopausal women (because the uricosuric effect of estrogen) and in African Americans (3). In malignancies, polycytemia vera or haemolytic anemias, the rapid cellular turnover determines excessive SUA production. Renal insufficiency is a common cause of SUA increase. Hyperuricemia is highly prevalent in chronic kidney disease, reflecting the reducing renal excretion of SUA. The use of diuretics, by causing volume contraction, increases the SUA level by increasing urate absorbtion. The data of the recent experimental and clinical studies suggest that SUA is not only a marker of reduced kidney function, but it is also a causal factor in the development and progression of renal disease (4). ❑

SUA AND CARDIOVASCULAR EVENTS

The relationship between SUA and the cardiovascular risk was demonstrated in many epidemiological studies (5). In the MONICA Ausburg study the increase in the SUA level was an independent factor for all causes of death and possible for the cardiovascular death (6). In the First National Health and Nutrition Study (NHANES I) study, for every 1.01 mg/dl increase in the SUA level, the hazard ratio for total mortality and for cardiovascular mortality were 1.09 and 1.19 for men and 1.26 and 1.3 for women, respectively (7). The result of the LIFE Study pointed out an association between the baseline SUA level and the risk of cardiovascular events in a high risk population with coronary artery disease(8). In the Multiple Risk Factors Intervention Trial (MRFIT), both hyperuricemia and gout were independent risk factors for myocardial infarction in 12866 men followed for 6.5 years (9).

In contrast, in the Atherosclerotic Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study and in the Framingham Heart Study there was no association between SUA and incident cardiovascular disease (10,11).

The difficulties in the assessment of the role of SUA independently from other traditional risk factors and the different methodologies used in the epidemiological studies may be responsible for the conflicting data regarding the relationship between the SUA level and cardiovascular disease. ❑

SUA AND HYPERTENSION

The association between arterial hypertension (HT) and hyperuricemia is very common. It has been reported that 25-40% of patients with untreated HT and more than 80% of patients with malignant HT have high SUA levels (12). Hyperuricemia is more common in primary HT, especially in patients with HT of recent onset and in preHT associated with microalbuminuria (13). Many mechanisms are involved in high SUA level in HT. The reabsorbtion of the urate in the proximal tubule is increased as a consequence to the reduced renal blood flow. The microvascular renal disease leads to tissue ischemia and to the up-regulation of XO with increased the SUA production. The reduction of the SUA secretion in the proximal tubule and the use of diuretics may increase the SUA level.

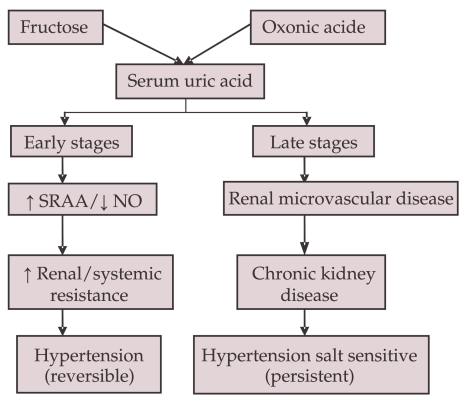

Several experimental studies have indicated that hyperuricemia per se can induce HT. In rats the high SUA level induced HT after several weeks (14). The HT was reversed after the normalization of SUA with allopurinol or with an uricozuric drug. Two main mechanisms are involved in the hyperuricemia-induced HT (FIGURE 2). In early stage the high SUA level induces renal vasoconstriction by the activation of the renal RAAS and by the endothelial dysfunction with decreased nitric oxide level at the macula densa. In this stage, HT is salt-resistant and it is reversed by lowering the SUA level. In later stage chronic hyperuricemia induces vascular muscle cell proliferation and local activation of RAA system with the activation of the mediators of inflammation. Progressive microvascular renal disease is associated with afferent arteriolosclerosis and with interstitial fibrosis (15, 16). The renal histopathologic changes in chronic hyperuricemia are similar to those induced by HT. HT becomes salt-driven and renal-dependent and it is not normalized by lowering SUA.

Figure 2.

Relationship between oxonic acid and fructose induced hyperuricemia, hypertension and chronic kidney disease (57)

Several clinical studies demonstrated that hyperuricemia precedes and it is associated with the development of HT. In the Framingham Heart Study, each increase in SUA by 1.3 mg/dl was associated to the development of HT with an odd ratio of 1.17 (17). In the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention (MRFIT) study, in normotensive men with the SUA level greater than 7 mg/dl there was an 80% increased risk for the development of HT (18). The association between hyperuricemia and HT was more common in young people. The high SUA was observed in nearly 90% of adolescents with primary HT and the SUA level correlates with both systolic and diastolic HT (19, 20). In a study including adolescents with HT of recent onset and hyperuricemia, the reduction in SUA to less than 5 mg/dl with allopurinol was associated to the reversal of HT in 86% of the patients (21). ❑

SUA AND METABOLIC SYNDROME, INSULIN RESISTANCE AND DIABETES

Epidemiological and clinical studies have establish a close link between the high SUA level and the increasing prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and all its individual components (glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, abdominal obesity, atherogenic dyslipidemia and HT) (22,23). In the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the metabolic syndrome was prevalent in persons with normal body mass index at different SUA levels (24). The prevalences of the metabolic syndrome was 18.9% for the SUA levels less than 6 mg/dL and 70.7% for the SUA levels of 10 mg/dL or greater. Moreover, hyperuricemia might independently predict the development of different components of the metabolic syndrome – obesity, hyperinsulinemia and diabetes (25-27).

The elevated SUA level observed in the metabolic syndrome has been attributed to hyperinsulinemia, since insulin reduces renal excretion of uric acid. In animal studies, hyperuricemia might induce metabolic syndrome by two mechanism. Firstly, hyperuricemia may have a causal role in the pathogenesis of insulin-resistance. High level of SUA inhibit endothelial NO bioavailability and insulin requires endothelial NO to stimulate skeletal muscle glucose up-take. Secondly, hyperuricemia induces oxidative and inflammatory changes in adipocytes, inducing metabolic syndrome in obese mice (28). ❑

SUA AND ATHEROSCLEROSIS

The pathophysiological link between the elevated SUA and atherosclerosis are endothelial dysfunction and inflammation. ROS production by XO can induce endothelial dysfunction by reducing bioavailability of nitric oxide (33). SUA, by its antioxidant properties, could counteract ROS generation. There are also evidences in animal experiments that the high SUA impairs endothelial dependent vasodilatation (34). An independent association between the SUA level and C-reactive protein and other inflammatory markers (blood neutrophils, interleukin, TNF-alfa) has also been described (35,36). So far there is evidence that the increased SUA level is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis.

The relationship between SUA and the development of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease was investigated in many studies. In NHANES I, ARIC and Rotterdam studies the high SUA level was associated with an increased risk of stroke ((7, 10, 29). In NHANES I study there was a 48% increase in the risk of ischemic stroke in women for every 1.01 mg/dl increase in SUA. In ARIC study there was an independent and positive relationship between the incidence of the ischemic stroke and SUA (10).

SUA as a risk factor for the developing CAD remains controversial. In MRFIT study, the hyperuricemia and gout had an independent relationship with the risk of myocardial infarction, after adjustments for other risk factors (9). In AMORIS study a moderate increase in the SUA level was associated with increased incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke and heart failure in middle-aged subjects without prior cardiovascular disease (31). Other studies (ARIC study, Framingham study or an Austrian study) did not found an independent association between the SUA levels and the increased risk of CAD (10, 11, 32).

The role of SUA as a causal factor for cardiovascular events in these conditions remains to be determined. ❑

SUA AND HEART FAILURE

Hyperuricemia is a common condition in chronic heart failure (CHF). It's prevalence increases as the disease progresses (37). In a cross sectional study, 51% of patients hospitalized from chronic heart failure had hyperuricemia (30). The SUA level is higher in patients with end-stage CHF and in cachectic patients (38). It is inversely associated with functional NYHA class and maximal oxygen consumption and it is significant correlated with the severity of diastolic dysfunction (38-42).

Hyperuricemia is also an independent prognostic marker in chronic and in acute heart failure (AHF) (43, 44). In a validation study, SUA was the most powerful predictor of survival for patients with severe CHF (NYHA class III or IV): in patients with high levels of SUA (> 9.5 mg/dl), the relative risk of death was 7.4 (44). In a study with AHF and systolic dysfunction the high SUA level was associated with higher risk of death and new heart failure readmission (45). Hyperuricemia was also an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in an unselected consecutive patients admitted with AHF (46).

Recently, hyperuricemia was associated to incident heart failure in community adults (47, 48). In the Cardiovascular Health Study the incident heart failure occurred in 21 % participants with hyperuricemia and in 18% participants without hyperuricemia. Each 1 mg/dl increase in SUA was associated to 12 % increase in incident heart failure (47). In the Framingham Offspring cohort, the incidence rates of heart failure were 6-fold higher among those at the highest quartile of SUA (>6.3 mg/dL) compared to those at the lowest quartile (<3.4 mg/dL) (48). Hyperuricemia appears as a novel, independent risk factor for heart failure in a group of young general community dwellers.

There are several mechanisms involved in hyperuricemia- induced heart failure. The increased SUA production may be due to increased XO substrate (ATP breakdown to adenosine and hypoxanthine) and to the up-regulation and increase in XO activity. SUA released from necrotic tissue can produce additional adverse effects on cardiovascular system and can mediate the immune response. (49). In heart failure hyperuricemia is a marker of XO activation (44).

Several studies have shown that the reduction in the SUA levels may be associated with the reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, the attenuation of the SUA levels by losartan was associated with 29% reduction in the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction and fatal or nonfatal stroke (50). Some of the cardiovascular benefits of atorvastatin reported in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary-Heart-Disease Evaluation (GREACE) study have also been attributed to the ability of statins to lower the SUA levels (51). Allopurinol and oxypurinol are XO inhibitors which has been used to treat hyperuricemia. The reducing the SUA level in HT with XO inhibitors lowers blood pressure in young with HT of recent onset (52). Other studies outline the potential benefits of XO inhibition in heart failure. In CHF allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction, peripheral vasodilatator capacity and myocardial energy by reducing markers of oxidative stress (52). In OPT-CHF Study oxypurinol increased left ventricular ejection fraction and improved clinical outcome in CHF patients presenting with high SUA levels (53). ❑

URIC ACID PARADOX

The uric acid has several biological properties which can be either beneficial or detrimental. SUA is a powerful antioxidant and it protects against free radical damage. Along with ascorbate, SUA accounts for up to 60% of the serum free radical scavenging capacity. SUA reacts with a variety of oxidants and it prevents the formation of peroxynitrite and the inactivation of the nitric oxid by superoxide anions. In individuals with hyperuricemia, the plasma total antioxidant capacity is elevated, which suggests that hyperuricemia may be a compensatory mechanism to counteract the oxidative stress damage related to atherosclerosis (54).

The SUA paradox consists in the fact that high SUA, which has antioxidant properties, is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. It has been proposed the theory of the antioxidant, pro-oxidant redox shuttle: SUA, which under normal circumstances is an antioxidant, becomes pro-oxidant in the atherosclerotic medium with ROS generation (55). The excess of SUA has deleterious effects: endothelial dysfunction, proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells, increases platelet adhesiveness, oxidation of LDL- cholesterol and lipid peroxidation. All these pathological processes might contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. ❑

CONCLUSION

Clinical and epidemiological evidences have shown that the SUA level is associated to cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease. Elevated SUA level has been recently recognized as a risk factor for the development of the arterial hypertension, subclinical atherosclerosis, stroke and heart failure. The role of the uric acid as an independent risk factor for the cardiovascular disease is controversial, since hyperuricemia is associated to other traditional risk factors. Elevated SUA level also represents a strong prognostic marker for cardiovascular events, particularly in patients at high cardiovascular risk or with established cardiovascular disease.

When associated with increase oxidative stress, hyperuricemia may be a marker of the increased XO activity. If SUA has a protective role as an antioxidant or a causative and deleterious role is still debatable. More prospective randomized trials lowering SUA are needed in order to clarify the role of the uric acid in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease and to establish if reducing SUA level will translate into a better cardiovascular outcome. Hyperuricemia will become then a meaningful target for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. ❑

References

- 1.Niskanen LK, Laaksonen DE, Nyyssönen K, et al. Uric acid level as a risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in middle-aged men: a prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1546–1551. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feig DI, Rang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamopoulos D, Vlassopoulos C, Seitanides B, et al. The relationship of sex steroids to uric acid levels in plasma and urine. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1977;85:198–208. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0850198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iseki K, Oshiro S, Tozawa M, et al. Significance of hyperuricemia on the early detection of renal failure in a cohort of screened subjects. Hypertens Res. 2001;24:691–697. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang J, Alderman, MH The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study, 1971-1992. JAMA. 2000;283:2404–2410. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liese AD, Hense HW, Lowel H, et al. Association of serum uric acid with all-cause and cardiovascular disease and incident myocardial infarction in the MONICA Augsburg cohort. World Health Organization monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular diseases. Epidemiology. 1999;10:391–397. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehto S, Niskanen L, Ronnemaa T, et al. Serum uric acid is a strong predictor of stroke in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Stroke. 1998;29:635–639. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoieggen A, Alderman MH, Kjeldsen SE, et al. The impact of serum uric acid on cardiovascular outcomes in the LIFE study. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan E, Baker JF, Furst DE, et al. Gout and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2688–2696. doi: 10.1002/art.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hozawa A, Folsom AR, Ibrahim H, et al. Serum uric acid and risk of ischemic stroke: the ARIC study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, et al. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RG. Uric acid and Cardiovascular Risk, N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JE, Kim YG, Choi YO, et al. Serum uric acid Is Associated With Microalbuminuria in Prehypertension. Hypertension. 2006 May;47:962–967. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000210550.97398.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001;38:1101–1106. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.092839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzali M, John Kanellis, Lin Han, et al. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002 Jun;282:991–997. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00283.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe S, Kang DH, Feng L, et al. Uric acid, hominoid evolution and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002;40:355–360. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000028589.66335.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundström J, Sullivan L, D'Agostino RB, et al. Relations of serum uric acid to longitudinal blood pressure tracking and hypertension incidence in the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005;45:28–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150784.92944.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eswar Krishnan, C Kent Kwoh, H Ralph Schumacher, et al. Hyperuricemia and Incidence of Hypertension Among Men Without Metabolic Syndrome. Hypertension. 2007 Feb;49:298–303. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000254480.64564.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feig DI, Johnson RJ. Hyperuricemia in childhood essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:247–252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000085858.66548.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold B, Alper Jr, Wei Chen, et al. Childhood Uric Acid Predicts Adult Blood Pressure: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Hypertension. 2005 Jan;45:34–38. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150783.79172.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.I Feig, B Soletsky, RJ Johnson. Effect of Allopurinol on Blood Pressure of Adolescents With Newly Diagnosed Essential Hypertension: A Randomized Trial. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler JG, Juzwishin KD, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Serum uric acid and coronary heart disease in 9,458 incident cases and 155,084 controls: prospective study and meta-analysis. PloS Med. 2005;2(3):e76–e76. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JW, Ford ES, Gao X, et al. Sugar-sweetened soft drinks, diet soft drinks, and serum uric acid level: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:109–116. doi: 10.1002/art.23245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi HK, Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with hyperuricemia. Am J Med. 2007;120:442–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuo K, Kawaguchi H, Mikami H, et al. Serum uric acid and plasma norepinephrine concentrations predict subsequent weight gain and blood pressure elevation. Hypertension. 2003;42:474–480. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000091371.53502.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carnethon MR, Fortmann SP, Palaniappan L, et al. Risk factors for progression to incident hyperinsulinemia: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, 1987-1998. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:1058–1067. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehghan A, van Hoek M, Sijbrands EJ, et al. High serum uric acid as a novel risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:361–362. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sautin YY, Nakagawa T, Zharikov S, et al. Adverse effects of the classical antioxidant uric acid in adipocytes: NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidative/nitrosative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C584–C596. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00600.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, et al. Uric Acid is a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:1503–1507. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221716.55088.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campeanu A, Iliesiu A, Nistorescu D, et al. Serum concentration of uric acid in patients hospitalized with chronic heart failure. Heart Failure Congress; 2010; Poster Session Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holme I, Aastveit AH, Hammar N, et al. Uric Acid and risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and congestive heart failure in 417 734 men and women in the Apolipoprotein MOrtality RISk study (AMORIS). Journal of Internal Medicine. 2009;226:558–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strasak A, Ruttmann E, Brant L, et al. Serum Uric Acid and risk of cardiovascular mortality: a prospective long-term study of 83 683 Austrian men. Clin Chem. 2008;54:273–284. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.094425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, Lutty GA. Measurement of endothelial cell free radical generation: evidence for a central mechanism of free radical injury in postischemic tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4046–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khosla UM, Zharikov S, Finch JL, et al. Hyperuricemia induces endothelial dysfunction and vasoconstriction. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1739–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Ble A, et al. Uric acid and inflammatory markers. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1174–1181. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Miller E, et al. Usefulness of uric acid to predict changes in C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in 3-year period in Italians aged 21 to 98 years. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoeper MM, Hohlfeld JM, Fabel H. Hyperuricaemia in patients with right or left heart failure. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:682–685. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13368299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lainscak M, von Haehling S, Anker SD. Natriuretic peptides and other biomarkers in chronic heart failure: From BNP, NT-proBNP, and MR-proANP to routine biochemical markers. International Journal of Cardiology. 2009;3:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leyva F, Anker SD, Swan JW, et al. Serum uric acid as an index of impaired oxidative metabolism in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:858–865. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Florea VG, et al. Uric acid in cachectic and noncachectic patients with chronic heart failure: relationship to leg vascular resistance. Am Heart J. 2001;141:792–799. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurata A, Shigematsu Y, Higaki J. Sex-related differences in relations of uric acid to left ventricular hypertrophy and remodeling in Japanese hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:133–139. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Rossi A, et al. Elevated serum uric acid levels are associated with diastolic dysfunction in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, American Heart Journal. 2002;143:1107–1111. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.122122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stefan D Anker, Andrew JS Coats. Metabolic, functional, and hemodynamic staging for CHF? The Lancet. 1996;348:1530–1530. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, et al. Uric acid and Survival in Chronic Heart Failure: Validation and Application in Metabolic, Functional, and Hemodynamic Staging. Circulation. 2003;107:1991–1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065637.10517.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pascual-Figal DA, Hurtado-Martinez JA, Redondo B, et al. Hyperuricaemia and long-term outcome after hospital discharge in acute heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alimonda AL, Núñez J, Núñez E, et al. Hyperuricemia in acute heart failure. More than a simple spectator? European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2009;20:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ekundayo OJ, Dell'Italia LJ, Sanders PJ, et al. Association between hyperuricemia and incident heart failure among older adults: A propensity-matched study. International Journal of Cardiology. 2010;142:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eswar Krishnan. Hyperuricemia and Incident Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:556–562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.108.797662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lippi G, Mantagna M, Franchini M, et al. The paradoxical relationship between serum acid uric and cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2008;392:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hrieggen A, Alderman MH, Kjeldsen SE, et al. The impact of serum uric acid on cardiovascular outcomes in the LIFE study. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1041–1049. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Athyros VG, Elisaf M, Papageorgiou AA, et al. Effect of statins versus untreated dyslipidemia on serum uric acid levels in patients with coronary heart disease: a subgroup analysis of the GREek Atorvastatin and Coronary-heart-disease Evaluation (GREACE) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:589–599. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Farquharson CA, Butler R, Hill A, et al. Allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106:221–226. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022140.61460.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hare JM, Mangal B, Brown J, et al. Impact of oxypurinol in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2301–2309. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lippi G, Mantagna M, Franchini M, et al. The paradoxical relationship between serum acid uric and cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2008;392:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nieto FJ, Iribarren C, Gross MD, et al. UA and serum antioxidant capacity: a reaction to atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson RJ, Kang DH, Feig D, et al. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension. 2003;416:1183–1190. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000069700.62727.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berbari AE. The role of uric acid in hypertension, cardiovascular events and chronic kidney disease. European Society of Hypertension. Scientific Newsletter: Update on. Hypertension Management. 2010;11:No49–No49. [Google Scholar]