Abstract

Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), a transcription factor, plays a key role in the pluripotency of stem cells. We sought to determine the function of KLF4 in T-cell development and differentiation by using T-cell-specific Klf4-knockout (KO) mice. We found that KLF4 was highly expressed in thymocytes and mature T cells and was rapidly down-regulated in mature T cells after activation. In Klf4-KO mice, we observed a modest reduction of thymocytes (27%) due to the reduced proliferation of double-negative (DN) thymocytes. We demonstrated that a direct repression of Cdkn1b by KLF4 was a cause of decreased DN proliferation. During in vitro T-cell differentiation, we observed significant reduction of IL-17-expressing CD4+ T cells (Th17; 24%) but not in other types of Th differentiation. The reduction of Th17 cells resulted in a significant attenuation of the severity (35%) of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in vivo in Klf4-KO mice as compared with the Klf4 wild-type littermates. Finally, we demonstrated that KLF4 directly binds to the promoter of Il17a and positively regulates its expression. In summary, these findings identify KLF4 as a critical regulator in T-cell development and Th17 differentiation.—An, J., Golech, S., Klaewsongkram, J., Zhang, Y., Subedi, K., Huston, G. E., Wood, W. H., III, Wersto, R. P., Becker, K. G., Swain, S. L., Weng, N. Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) directly regulates proliferation in thymocyte development and IL-17 expression during Th17 differentiation.

Keywords: transcription factor, T-cell homeostasis, autoimmune disease

The development and differentiation of T cells are tightly controlled processes and play an essential role in T-cell function (1, 2). One of the key indicators of this regulation is the stable number of T cells in the body. The regulation of T-cell numbers occurs during development in the thymus and in the maintenance of T cells in the periphery. In both of these stages, transcriptional factors have been implicated as the master regulators of these processes. While much has been learned about T-cell development and differentiation, the molecular basis for the control of T-cell numbers during development and differentiation remains poorly understood.

Recent studies indicate that cellular proliferation and differentiation in the thymus play a critical role in determining T-cell numbers. The transcription factors T-cell factor-1 (TCF1), E26 avian leukemia oncogene 1 (ETS1), and early growth response gene 3 (EGR3) have been shown to positively regulate thymocyte numbers, as mice deficient in Tcf1, Ets1, or Egr3 have a significant reduction of thymocyte numbers, but the mature T cells appear to be generally normal (3–5). In contrast, EGR1, another member of the EGR protein family, negatively regulates thymocyte numbers (6). Despite the differences in their physiological functions, the deletion of these genes is often linked to decreased survival and/or increased apoptosis and dysregulation of proliferation among thymocytes.

Mature thymocytes migrating out of the thymus are naive T cells. When CD4+ naive T cells are stimulated by antigen, they undergo differentiation down several distinct pathways, including Th1, Th2, Treg, Th17, and others (7–10). The generation of each subset is controlled by the presence of cytokines early in the response and the master transcription factors that establish and maintain the specific cytokine expression in these differentiated T cells. Th1 cells secrete IFN-γ and are controlled by the master transcription factor TBX21 (TBET; ref. 11). Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and are controlled by transcription factor GATA-3 (7). Regulatory T (Treg) cells suppress T-cell response and are controlled by FOXP3 (8). Th17 cells secrete IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, and often IL-22 (12), require transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-6 for their differentiation, and appear to be controlled by the nuclear orphan receptor ROR-γt (9). Furthermore, Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1; through interaction with ROR-γt; ref. 13), ROR-α (14), AHR (15), BATF (16), and IRF4 (17) positively regulate Th17-cell differentiation, whereas ETS1 (18) and GFI1 (19) negatively regulate Th17-cell differentiation. There is >90% loss of Th17 cells in Rorγt-null mice, indicating that Rorγt is a crucial but not a sole regulator for Th17-cell differentiation. Th17 cells play key roles in immune response to a variety of pathogens and to autoimmune inflammation (9, 10). For example, the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) has been attributed to IL-17 and Th17 cells (12, 20), as mice lacking IL-17 are resistant to the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-induced EAE (21). Reduced pathogenic Th17 responses have been shown to correlate with improved clinical outcome, including improved EAE clinical score and reduced infiltration of leukocytes into the central nervous system (CNS; refs.22, 23).

Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), a member of the highly conserved zinc finger-containing Krüppel-like factor family, plays an essential role in maintaining pluripotency of stem cells (24, 25) and in cell growth and differentiation (26). KLF4 regulates expression of a large number of genes with GC-rich sequences (G/AG/AGGC/TGC/T and CACCC; refs. 27, 28). In lymphocytes, KLF4 regulates B-cell numbers and activation-induced B-cell proliferation (29). However, the precise role of KLF4 in T-cell development and differentiation has not been examined directly. To assess this, we generated mice deficient in Klf4 in T cells (Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+) and studied KLF4 function in thymocyte development and Th-cell differentiation. We found modest but significant reductions in the number of thymocytes (27% less) and of splenic T cells (20% less) in Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre+ mice as compared with the wild-type Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre− mice. We further demonstrated that KLF4 directly binds Cdkn1b promoter and inhibits its expression. In the absence of KLF4, Cdkn1b expression increased in DN cells and resulted in reduced proliferation of DN thymocytes. Furthermore, we demonstrated that KLF4 is a positive regulator of Th17 differentiation. In the absence of Klf4, naive CD4+ T cells stimulated in vitro under Th17-polarizing conditions generated 24% fewer IL-17-producing cells compared with wild-type cells and consequently reduced severity of EAE (35% less) in KLF4-deficient mice compared with the wild-type mice. Finally, we demonstrated that KLF4 bound to the promoter of the Il17a gene and enhanced its expression. Collectively, these findings suggest that KLF4 regulates both thymic cellularity and Th17-cell differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre mice

Klf4fl/fl mice (30) were crossed with CD4-Cre mice (31) to generate Klf4fl/flCD4Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4Cre− (control) mice. Mice used for experiments were between 6 and 10 wk old and were housed in the animal facility of the Biomedical Research Center, National Institute on Aging (National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, USA). Maintenance of and experiments with mice were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health policies for animal care and use. Mice containing Klf4fl/fl and CD4-Cre were confirmed by PCR (JumpStart RedTag DNA polymerase; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the specific deletion of Klf4 in T cells was further confirmed by genomic DNA PCR of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice, as described previously (30). Successful deletion of Klf4fl/fl resulted in a 425-bp band, while the Klf4fl/fl allele without deletion gave a 296-bp product.

Isolation and stimulation of T cells

Thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes were isolated from mice, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were enriched with a CD4 or a CD8 T-cell isolation kit either from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA, USA) or from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, BC, Canada). The purity of these isolated cells was >95%. Freshly isolated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were resuspended in RPMI1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and stimulated with anti-CD3 (clone 2C11, 10 μg/ml; gift from Richard Hodes, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) and anti-CD28 (10 μg/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) and were harvested at specified times for mRNA, protein, and other analyses.

Flow cytometry and antibodies

Cells isolated from thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes were stained with the appropriate antibodies for 30 min at 4°C. Data were collected by FACS Calibur and analyzed by the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The following antibodies were used: APC-conjugated CD4 (L3T4), FITC-conjugated CD44 (Pgp-1; eBioscience), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD8a (Ly-2; BD Bioscience), and FITC-conjugated CD19 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD62L (Invitrogen).

In vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling and apoptosis assay of thymocytes

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 180 μl of BrdU solution (10 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) and were killed 2 h later. Single-cell suspensions of thymus were prepared and stained in the following sequence: antibody against CD4 and CD8, fixed, permeabilized, and treated with DNase I (Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C, and then incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU (BD Bioscience) for 20 min at room temperature. For analysis of apoptosis, freshly isolated thymocytes were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8, then resuspended in annexin V binding buffer, and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-annexin V (BD Bioscience) for 20 min at room temperature. Cells were washed and immediately analyzed by FACS Calibur.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from thymocytes and from resting and stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Reverse transcriptase (SuperScript III; Invitrogen) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA from total RNA. cDNA was used for the real-time quantitative PCR analysis using the FG Power SYBR Green PCR master mix on the ABI7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Primers used were as follows: Klf4, 5′-TCACACAGGCGAGAAACCTT-3′ and 5′-GAGCGGGCGAATTTCCA-3′; β-actin, 5′-AGGTCATCACTATTGGCAACGA-3′ and 5′-AGGATTCCATACCCAAGAAGGAA-3′; Cdkn1b, 5′-GGCCAACAGAACAGAAGAAAATG-3′ and 5′-GGGCGTCTGCTCCACAGT-3′; Il17a, 5′-TCAATGCGGAGGGAAAGCT-3′ and 5′-GCTCTCAGGCTCCCTCTTCAG-3′.

Western blot

Cells were lysed in NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA), and 15 μg protein from each sample was used for Western blot. The dilution of anti-KLF4 was 1:500 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), the dilution of anti-fibrillarin was 1:1000 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and anti-CDKN1B (p27Kip1) was 1:1000 (BD Biosciences). Signals were detected using the ECL detection system and film (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The quantitation was carried out using FluorChem imaging system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA) with normalizing on the intensity of fibrillarin.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was extracted from freshly isolated DP+SP4 thymocytes using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The quality and quantity of total RNA were analyzed by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using RNA 6000 nanochips (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Mouse whole-genome chip (MouseRef-8 v2.0 Expression BeadChip Kits; Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used. Microarray data were analyzed, and expression changes for individual genes were considered significant if they met 3 criteria: Z ratio > 2.0 or < −2.0; P < 0.05; and mean background-corrected signal intensity > 0 (32).

CD4+ T-cell differentiation in vitro

Naive CD4+ T cells were enriched from isolated CD4+ T cells (described in preceding section) by anti-CD62L (L-selectin) microbeads using an autoMACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec). The in vitro differentiation conditions for Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg followed previously published procedures (11, 33, 34). Numbers of IFN-γ-, IL-4-, IL-17-, and FOXP3-producing CD4+ T cells were determined by intracellular staining with anti-IFN-γ (FITC), anti-IL-4 (PE), anti-IL-17 (PE), and anti-FOXP3 (FITC) (eBiosciences). Data were collected by FACS Calibur and analyzed by CellQuest (BD Biosciences) or FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA). Cytokine production in cell culture supernatants was measured by ELISA with mouse IFN-γ and IL-17A ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit with precoated plates (eBioscience).

Chromatin immunopreciptation (ChIP) assay

The procedure for the ChIP assay was described previously (35). The following formula was used for quantitation of ChIP results: input % = 2Ct input − Ct ChIP × 100. Primers were as follows: Cdkn1b_1, 5′-GACTTCTGGGGTCAGGCTAAGC-3′ and 5′-GGAAACCTTGGCTCAGGGC-3′; Cdkn1b_2, 5′-TTGTAGTTGGCGTCTGGACTCAG-3′ and 5′-TGGTTCCTAAGCACAGTGAAAGC-3′; Il17a_1, 5′-CCGTCATAAAGGGGTGGTTC-3′ and 5′-CGTCAAGAGTGGGTTGGGG-3′; Il17a_2, 5′-CAATGTTGTGGTATGTTTATTCCAG-3′ and 5′-CTTTCACCCTGTTTATCAGCAC-3′.

Promoter reporter construction and luciferase reporter assay

A 1-kb DNA fragment of Cdkn1b proximal promoter was cloned and ligated into pGl4.10 firefly luciferase vector with BglII and HindIII restriction enzyme sites. A 2-kb DNA fragment of Il17a proximal promoter in pGl4.10 firefly luciferase vector was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA, USA; ref. 13). Both the Cdkn1b and Il17a promoter constructs were verified by sequencing. Mouse Klf4 gene was purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD, USA) and verified by sequencing. Klf4- and control vector-expressing cells were established by transfecting stable Klf4-expressing vector and the control vector into Jurkat cells using a Nucleofector II (Lonza, Mapleton, IL, USA). In a typical study, 3 × 106 stable Klf4-expressing cells and control cells in 100 μl Amaxa solution V were transfected with 2 μg Cdkn1b and Il17a promoter luciferase reporter or respective control vector and 1 μg Renilla luciferase reporter. Transfected cells were incubated overnight and then lysed for measurement of luciferase activity by a dual luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

EAE induction, scoring, and evaluation

The procedure for inducing EAE in mice was previously described (19, 23). Briefly, each mouse was injected subcutaneously with 200 μg MOG33–35 peptide (AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA), 400 μg Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco, Surrey, UK), plus 400 ng pertussis toxin (Sigma) intraperitoneally on d 0. On d 2, the mice received another injection of 400 ng pertussis toxin. Experimental mice were labeled by a code, and the clinical symptoms were scored without knowing the genotype of these mice. Scores for the severity of symptoms were as follows: 0, no signs of disease; 1, tail paralysis; 2, hindlimb weakness; 3, hindlimb paralysis; 4, forelimb paralysis; 5, moribund or death. Gradations of 0.5 were utilized for mice exhibiting symptoms falling between two of the scores. For MOG recall assay, splenocytes were restimulated with MOG peptide for 3 d and then were activated with PMA (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μM) in the presence of monesin (2 μM) for 4 h. The intracellular cytokine was stained and analyzed by FACS. The procedure for isolation of infiltrated leukocytes from brains was as described previously (36); mice were perfused with 25 ml cold PBS to remove blood before brain dissection.

Statistical analysis

Student's t test was used to analyze the statistical differences between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice, and values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

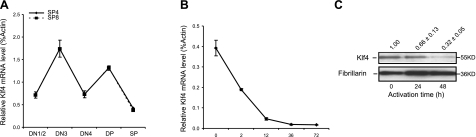

Expression of KLF4 during T-cell development and activation

To assess the expression of KLF4 during T-cell development and activation, thymocyte subsets and peripheral T cells were isolated from wild-type mice by cell sorting, followed by in vitro activation. In thymocytes, the Klf4 mRNA expression oscillated in the DN (CD4−CD8−), DP (CD4+CD8+), SP4 (CD4+CD8−), and SP8 (CD4−CD8+) subsets during T-cell development (Fig. 1A). Similar fluctuations of expression level also have been observed in two other Klf family members, Klf3 (37) and Klf13 (38). In the periphery, naive CD4+ T cells from spleen expressed amounts of Klf4 mRNA comparable to the levels expressed by thymocyte subsets (SP4 and SP8). After activation, Klf4 mRNA was rapidly decreased by 2 h and reached the lowest level at 36 h after stimulation with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 (Fig. 1B). In parallel with the mRNA level, KLF4 protein levels were decreased dramatically in CD4+ T cells after stimulation (Fig. 1C). Together, these findings showed that the expression of KLF4 is actively regulated in T-cell development and activation.

Figure 1.

KLF4 expression is actively regulated during thymocyte development and in peripheral CD4+ T-cell activation. A) Klf4 mRNA levels in thymocyte subsets. Thymocyte subsets (DN1/2, DN3, DN4, DP, SP4, and SP8) were isolated from thymus of wild-type Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice by sort. Klf4 mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR and normalized to β-actin. Data represent 3 individual experiments with 4 mice/experiment (n=4). B) Klf4 mRNA levels in peripheral naive CD4+ T cells before and after stimulation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 2, 12, 36, and 72 h in vitro. Naive CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleen of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice by sort. Data represent 2 independent experiments with 6 mice/experiment (n=6). C) Decreased KLF4 protein levels in CD4+ T cells after anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. Nuclear proteins were extracted from resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Western blot image is representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are relative mean intensity values. Error bars = means ± se.

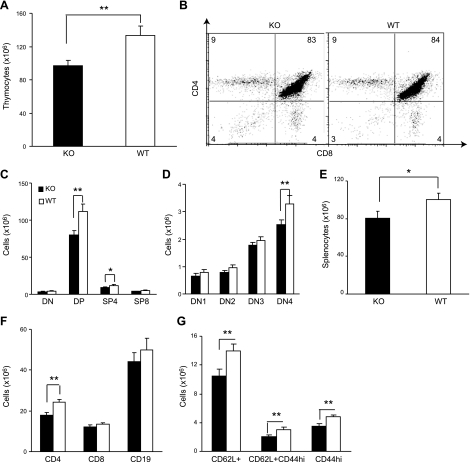

Reduction of thymocytes and peripheral T cells in Klf4 conditional-knockout mice

To analyze the role of KLF4 in T-cell development, we generated mice with Klf4 deletion specifically in T cells by crossing floxed Klf4 mice (39) with CD4-Cre transgenic mice (31). The resulting Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice were analyzed with wild-type Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− littermates as control. Deletion of the Klf4 gene in T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice was confirmed at the levels of genomic DNA, mRNA, and protein in T cells (Supplemental Fig. S1A–C). A 27% reduction in the number of total thymocytes was observed in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ as compared with Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre− mice (n=10; P<0.01; Fig. 2A). However, the percentages of thymocyte subsets were similar between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 2B and Supplemental Fig. S1D). As CD4-Cre-mediated deletion occurred at the late stage of DN thymocytes (40, 41), we found that the Klf4 deletion in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice occurred at the DN3 subpopulation (Supplemental Fig. S1E) and observed significant reductions in numbers of DN4, DP, and SP4 thymocytes between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 2C–D). Reduction of SP8 populations was observed, but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2C). There were no substantial changes in numbers and percentages of natural killer T (NKT), γδ T, and Treg cells in thymus between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Supplemental Fig. S1F, G).

Figure 2.

Reduction of thymocyte and peripheral CD4+ T-cell numbers in T-cell-specific Klf4 conditional-knockout mice. A) Decrease of total thymocyte number in Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre+ (KO) mice compared with control Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre− (WT) mice. Thymocytes were isolated from 6- to 10-wk-old KO and WT mice and were counted by trypan blue exclusion method (n=10). B) Similar percentages of thymocyte subsets (DN, DP, SP4, and SP8) between KO (left) and WT (right) mice. Thymocytes were stained with antibodies against CD4 and CD8; dot plot is representative. Numbers represent percentages of cells (n=10). C) Decrease of DP and SP4 thymocytes in KO mice compared with control WT mice. Thymocytes were stained with antibodies against CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD44. Thymocyte numbers of each subset were extrapolated from the percentage of each subset and the total number of thymocytes (n=10). D) Decrease of DN4 thymocyte subset in KO mice compared with control WT mice. Same experimental design as in C. E) Decrease of total splenocytes in KO mice compared with control WT mice (n=10). Splenocytes from individual mice were isolated and counted by the trypan blue exclusion method. F) Decrease of T cells (CD4+ significant and CD8+ to a lesser degree) but not B cells in spleen of KO compared with control WT mice (n=10). Splenocytes were stained with antibodies against CD4, CD8, CD19, CD62L, and CD44; cell numbers were extrapolated from the percentage of each subset and the total number of splenocytes. G) Decrease of subsets of CD4+ T cells in KO mice compared with control WT mice (n=10). All data are means ± se. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 2-tailed Student's t test.

To further determine whether the number of T cells in the periphery was also affected in the absence of KLF4, we analyzed lymphocytes from spleen and lymph nodes. The number of lymphocytes in spleen was also significantly decreased (20%) in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice as compared with Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 2E). Similar to the thymocytes, the reduction of CD4+ T cells (26%) was more profound than the reduction of CD8+ T cells (9%) in the Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice (Fig. 2F). Within the CD4+ T cells, both naive (CD62L+) and memory (CD44high) phenotypes were reduced significantly (Fig. 2G). In contrast, the number of B cells in the spleen was not significantly changed between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice.

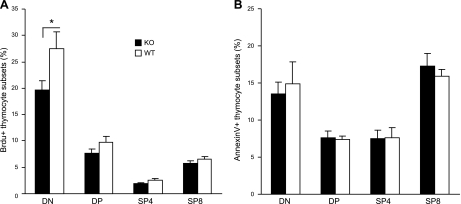

Reduced proliferation and increased CDKN1B expression in thymus of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice

To determine the mechanism underlying the reduction of thymocytes in the absence of KLF4, we analyzed thymocyte proliferation and apoptosis. Using a BrdU pulse method, we found significantly fewer BrdU-labeled proliferating thymocytes (DN) from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ than from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 3A). However, we did not observe significant differences in the percentage of apoptotic thymocyte subsets from Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice by the annexin V-staining method (Fig. 3B). Together, these results suggest that the reduction of thymocytes in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice may be due to reduced cell division of thymocytes at the late DN stage.

Figure 3.

Decreased proliferation but no increased apoptosis of thymocytes in the absence of KLF4. A) Decreased BrdU-labeled thymocytes at the DN stage of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+compared with the Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with BrdU and killed 2 h later. Thymocytes were isolated and stained with CD4 and CD8, fixed and permeabilized, and stained with anti-BrdU after treatment with DNase I (n=8). B) No increased apoptosis of thymocyte subsets. Freshly isolated thymocytes were stained with antibodies against CD4, CD8, and annexin V and gated on DN, DP, SP4, and SP8 cells, respectively (n=10). Data are means ± se. *P < 0.05.

To further ascertain the transcriptional changes that might be responsible for the decreased thymocyte proliferation, we carried out microarray experiments comparing gene expression profiles of thymocytes from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice. The overall gene expression changes in the absence of Klf4 were relatively small, as reflected in the number of genes that differed and in the degree of altered expression level (GEO Accession No. GSE24880). This is reminiscent of the gene expression changes observed in the absence of Klf13 (42), suggesting that the effect of an individual Klf member on overall gene expression is mild. Although we did not find significant alteration in the expression of other Klf members (Supplemental Fig. S2A), it is possible that there was some degree of functional compensation from other KLF family members in the absence of KLF4. For genes whose expression levels differed significantly between Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice, we further determined whether the KLF4 binding motif (G/AG/AGGC/TGC/T and/or CACCC; refs. 27, 28, 43) exists in their promoters as an indicator of potential direct regulation by KLF4.

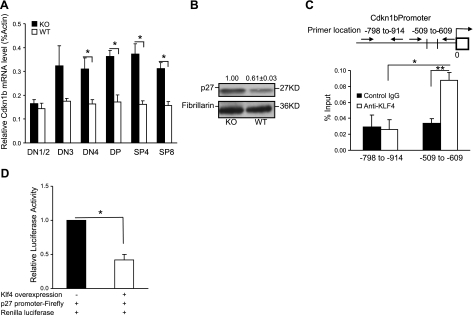

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1b (CDKN1B, p27Kip1) had 2 putative Klf4 binding sites at the proximal promoter and was significantly increased in thymocyte subsets (DN4, DP, SP4 and SP8) at mRNA and protein levels (DP+SP4) in the absence of KLF4 (Fig. 4A, B). Using ChIP assay, we demonstrated that KLF4 directly binds the promoter of Cdkn1b (Fig. 4C). To further determine whether the binding of KLF4 at the Cdkn1b promoter negatively regulates Cdkn1b expression, we established a KLF4-overexpressing cell line and tested with the Cdkn1b promoter reporter that contains a 1-kb sequence upstream of the transcription starting site (TSS) of Cdkn1b. We found a significant decrease of Cdkn1b reporter activity in the presence of KLF4 (Fig. 4D). This finding is in good agreement with a previous report that the levels of Cdkn1b determine the number of thymocytes in the Cdkn1b transgenic mouse model (44). Here we demonstrated that KLF4 is a negative regulator of CDKN1B in thymocytes, and the increased expression of CDKN1B in the absence of Klf4 is at least partially responsible for the reduction of thymocytes.

Figure 4.

Increased expression of CDKN1B in thymocytes in the absence of KLF4. A) Cdkn1b mRNA levels in different thymocyte subsets of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ (KO) and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− (WT) mice. Thymocyte subsets were isolated by sort, and the Cdkn1b mRNA level was determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (n=12). B) CDKN1B protein level in thymocytes of KO and WT mice. Total proteins were extracted from the DP (with some SP4) thymocyte subset, and CDKN1B protein was determined by Western blot. Representative image from 3 independent experiments, and relative mean intensity values of each band. C) KLF4 binds to the promoter of Cdkn1b gene. Diagram of the putative KLF4 binding sites at the promoter of the Cdkn1b gene is indicated by the cross lines. Arrows indicate the location of the specific and control primers used for ChIP assay. ChIP assay and quantitative PCR were conducted with an antibody against KLF4 and an isotype-matched IgG as control (n=6). D) KLF4 negatively regulates Cdkn1b expression. Dual luciferase reporter assay was used for testing the KLF4 effect on Cdkn1b promoter, as described in Materials and Methods (n=8). Data are means ± se. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Defects in Th17 differentiation in the absence of Klf4

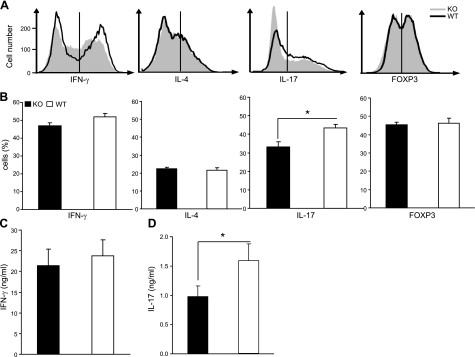

To determine whether KLF4 plays a role in regulating T-cell differentiation, we analyzed differentiation of naive CD4+ T (CD4+ CD62L+) cells from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice under Th1-, Th2-, Treg-, and Th17-polarizing conditions in vitro and used intracellular cytokine staining as indication of the differentiation process in polarized effector cells. Naive CD4+ T cells from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice yielded comparable numbers of Th1, Th2, and Treg effectors but fewer Th17 cells than from the Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 5A, B). Under Th17 differentiation conditions, ∼24% reduction of IL-17+ CD4+ T cells was observed from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice (33.2±2.6%) compared with the counterparts from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (43.4±2.0%; Fig. 5B) but there was no significant difference in IFN-γ production (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the reduction of IL-17+ cells from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice correlated with decreased IL-17 protein concentration in the supernatant of Th17 cells (Fig. 5D), indicating that KLF4 regulates Il17 expression.

Figure 5.

KLF4 regulates Th17- but not Th1-, Th2-, and Treg-cell differentiation. A) Histograms of Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ (KO) and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− (WT) mice. Numbers of Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells were determined by intracellular staining with anti-IFN-γ, anti-IL-4, anti-IL-17 and anti-FOXP3. Gates for each subset were set according to each isotype-matched control Ab staining. B) Mean percentages of positive cells for the indicated Th cytokines from KO and WT mice (n=8). C) No significant difference of IFN-γ concentration in the supernatant of 4 h PMA/ionomycin restimulated Th1-polarized cells from KO mice compared with cells from WT mice (n=8). D) Decreased IL-17 concentration in the supernatant of 4 h PMA/ionomycin restimulated Th17 polarized cells from KO mice compared with cells from WT mice. IFN-γ and IL-17 concentrations were measured by ELISA (n=8). Data are means ± se. *P < 0.05.

Reduced severity of EAE in KLF4 conditional-knockout mice

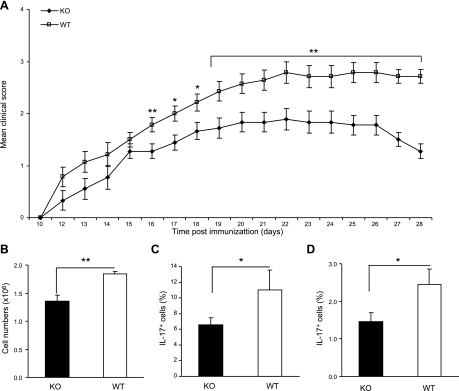

To determine the effect of the reduced Th17 differentiation in vivo, we used the EAE model by immunizing Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice with a peptide of MOG. Although the onset of the disease was similar, Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice displayed significantly less severity of disease (reduced by 35%) compared with Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice, as measured by the scores of the symptoms (Fig. 6A). At the peak of disease (from d 18 to 28 after induction), the average score of Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice was 1.7 ± 0.1, whereas that of control Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice was 2.6 ± 0.1. Furthermore, the infiltration of leukocytes into the brain, a sign of pathogenesis, was significantly reduced in Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre+ mice compared with Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 6B). To determine whether the reduction of Th17 cells in vivo in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice contributed to the reduced severity of EAE, we isolated brain-infiltrating cells and found a lower percentage of IL-17+ T cells in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice than in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 6C). We also isolated splenocytes from EAE mice to evaluate the generation of MOG-specific Th17 cells and found that IL-17+ T cells were significantly fewer in the splenocytes from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice than in Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Fig. 6D). To determine whether Th1 cells were also involved in the EAE pathogenesis, we examined IFN-γ+ T cells in CNS and IFN-γ concentration in supernatant of the infiltrating cell culture. We did not find significant differences in the percentage of IFN-γ+ T cells in CNS and the IFN-γ concentration in supernatant of infiltrating cells (Supplemental Fig. S3A, B).

Figure 6.

Klf4 deletion attenuates the severity of EAE. A) Improved clinical EAE score from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ (KO) compared with Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− (WT) mice. Data are means ± se of 3 individual experiments with 9 mice in each group (n=9). B) Reduced leukocyte infiltration in brain from KO compared with WT EAE mice. Total brain infiltrated mononuclear leukocytes were counted. Data represent 2 independent experiments (n=6). C) Fewer IL-17-producing T cells in brain-infiltrating cells from KO than WT EAE mice. Brain-infiltrated mononuclear leukocytes were stimulated in vitro with PMA plus ionomycin for 4 h and then stained with antibody against IL-17. Data are mean percentages of IL-17+ cells (n=6). D) Decreased IL-17 producing cells from the spleen of KO compared with that of WT EAE mice. MOG recall assay was performed using splenocytes derived from each group restimulated with MOG peptide for 3 d, and intracellular cytokine staining was assessed by FACS (n=9). Data are means ± se. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Direct regulation of Il17a expression by KLF4

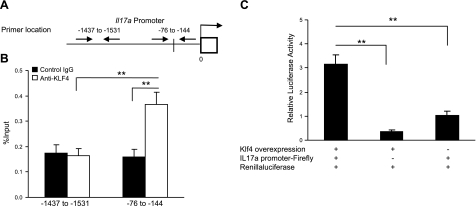

Several transcription factors have been implicated in the regulation of Th17 differentiation (9, 13–19). To delineate the role of KLF4 in Il17a expression directly or indirectly through regulation of other transcription factors, we analyzed the expression of Rorγt and other factors, including Runx1, Rorα, Batf, AhR, Irf4, Ets1, and Gfi1, and found that none was significantly changed in the absence of KLF4 (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Furthermore, we failed to demonstrate a direct binding of KLF4 to the putative sites on the promoter of Rorγt (Supplemental Fig. S2C, D), suggesting that KLF4 may regulate Th17 differentiation either downstream of these factors or directly at the Il17a gene.

To determine whether Klf4 directly regulates Il17a expression, we analyzed the Il17a promoter and identified a putative KLF4-binding sequence (CACCC) at −80 bp of the TSS of Il17a (Fig. 7A). Using the ChIP assay, we demonstrated a direct and specific binding of KLF4 to this putative site on the promoter of Il17a (Fig. 7B). To further determine whether the binding of KLF4 at the Il17a promoter induces its expression, we used the KLF4-overexpressing cell line and tested with the Il17a promoter reporter that contains a 2-kb sequence upstream of the TSS of Il17a. Indeed, a significant increase of Il17a reporter activity was observed in the presence of KLF4 (Fig. 7C). Together, these findings indicate that KLF4 directly enhances Il17a expression during CD4+ T-cell differentiation.

Figure 7.

KLF4 positively regulates Il17a expression by directly binding to the Il17a gene. A) Diagram of the putative KLF4 binding sites at the Il-17a gene promoter. Line crossing the promoter region indicates the putative KLF4-binding sites. Arrows indicate locations of specific and control primers used for ChIP assay. B) Specific binding of KLF4 to the promoter of Il17a gene in polarized Th17 cells. ChIP assay and quantitative PCR were conducted with an antibody against KLF4 and an isotype-matched IgG as control. One putative binding site and one nonputative binding site were examined for Il17a gene. C) KLF4 positively regulates Il17a expression. Dual luciferase reporter assay was performed as described. Data are means ± se (n=8). **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the function of transcription factor KLF4 in T-cell development and differentiation. We found that KLF4 expression is tightly regulated during T-cell development and is reduced dramatically on activation of mature peripheral T cells. T-cell-specific Klf4 conditional-knockout mice have decreased thymic cellularity and reduced T-cell numbers in spleen due partly to the reduced proliferation of DN thymocytes. We demonstrated that KLF4 directly binds the promoter of Cdkn1b and negatively regulates its expression. In the absence of KLF4, DN thymocytes significantly increased expression of Cdkn1b, which in turn reduced proliferation of DN thymocytes. Moreover, we found a significant decrease of Th17 cells during in vitro differentiation in the absence of Klf4. In agreement with the role of Th17 cells in autoimmune diseases, we observed a significant reduction of Th17 cells in vivo in EAE and in the severity of EAE in Klf4 conditional-knockout mice. Finally, we demonstrated that KLF4 directly bound the Il17a gene promoter and enhanced its expression during Th17-cell differentiation.

Reduction of the number of thymocytes has been observed in a number of gene-deficient mice. One of the common causes is a differentiation block of the transition of thymocytes from one stage to the next, such as transition from the DN to DP in Egr-3-null mice (5). Another commonly observed change is a decrease in survival or increased apoptosis of thymocytes, such as was found in Rorc-null mice (45, 46). The increase of apoptosis in thymocytes from Rorc−/− mice has been attributed to the reduced expression level of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-XL (46). It is known that KLF2, a close relative of KLF4, is involved in T-cell trafficking of thymocytes. Deficiency of KLF2 leads to the impaired expression of receptors such as sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor S1P1, cell adhesion molecules (SELL and ITGB7), CCR3, and CCR5, which are required for T-cell emigration and peripheral trafficking (47, 48). Here, we showed a modest reduction of thymocytes in the absence of KLF4 without an obvious development block and enhanced apoptosis. However, there was a significant decrease of proliferation of DN thymocytes, suggesting that KLF4 plays a different role from those previously reported factors.

Comparative analysis of the gene expression profile of thymocytes in the presence and absence of KLF4 revealed the alteration of genes involved in cell cycle regulation, such as Cdkn1b, Ccng1, and others of great interest. It has been reported that Cdkn1b transgenic mice have reduced numbers of DP, SP4, and SP8 as well as mature T cells and that the degree of reduction of thymocyte numbers is directly dependent on the level of CDKN1B expression (44). Thus, a modest increase of CDKN1B is likely a major cause for the modest reduction of thymocytes and mature T cells in the KLF4-deficient mice. Interestingly, in direct contrast to the negative regulation of CDKN1B expression by KLF4 in thymocytes demonstrated here, it had been reported that KLF4 positively regulates Cdkn1b expression in human pancreatic cancer cells (49). This difference is reminiscent of the context-dependent effect of KLF4 in the regulation of p53 (50). Further study will be needed to determine whether other altered expressed cell cycle regulators also contribute to thymocyte cell cycle and numbers in Klf4 conditional-knockout mice.

The differentiation process of Th17 cells has been extensively analyzed in recent years. In mice, Th17-cell differentiation is induced by the combined activity of IL-6 and low levels of TGFβ (9). These signals lead to the expression of ROR-γt, which in turn binds to the promoter and activates expression of Il17a. A recent study (13) also shows that RUNX1 interacts with ROR-γt for positive regulation of Th17-cell differentiation or interacts with FOXP3 for negative regulation of Th17-cell differentiation. In the absence of KLF4, we found that naive CD4+ T cells differentiated into effectors with fewer numbers of IL-17-secreting cells after in vitro induction but without affecting other Th subsets. Furthermore, this reduction of Th17 cells did not appear to be caused by decreased proliferation, as the number of total polarized cells and mRNA level of Cdkn1b in polarized cells were similar between Klf4fl/fl CD4-Cre+ and Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre− mice (Supplemental Fig. S4). Strikingly, even though the decrease of Th17-cell generation was mild under in vitro conditions, we observed a rather substantial effect on the severity of EAE symptoms and pathogenesis in vivo in the Klf4 conditional-knockout mice compared with the wild-type mice. The role of KLF4 in Th17-cell differentiation was further clarified by the demonstration that KLF4 directly binds to the promoter of the Il17a gene and enhances its expression. Recently, Lebson et al. (51) used the conventional KLF4-knockout mice with bone marrow chimeras and reported that IL-17 production required the presence of KLF4, which appeared to be independent of the ROR-γt pathway of regulating IL-17 expression. The reduction of IL-17-expressing cells in their chimeric mice was more severe than in the conditional KLF4-knockout mice observed here, which may be due to the incomplete deletion of KLF4 under CD4-cre conditions (92±1% deletion of KLF4 in naive CD4+ T cells from Klf4fl/flCD4-Cre+ mice; Supplemental Fig. S1E). Together, these findings suggest that the action of KLF4 in regulation of Th17 differentiation is either independent of or downstream from the ROR-γt or other tested factors. Our preliminary computational analysis suggested a putative ROR-γt binding site at the promoter of Klf4, but it remains to be determined whether this site is functional in regulation of KLF4 expression by RORγt.

In addition to ROR-γt and RUNX1, it has been reported that ETS1 (18) and GFI1 (19) negatively regulate Th17 differentiation and that RORα (14), AHR (15), BATF (16), and IRF4 (17) positively regulate Th17-cell differentiation. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the regulation of Il17a expression is complex, as several transcription factors are capable of positively or negatively regulating Il17a expression. However, the precise relationship of these transcription factors and their relative contribution to Th17 differentiation require further study. A better understanding of the role of KLF4 in the regulation of thymocyte numbers and Th17-cell differentiation will shed new insight into the mechanisms of thymocyte development, inflammatory response, and autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Richard Hodes and Joyti Sen for critical reading of the manuscript, Andrea Wurster and Qing Yu for help with Th2- and Th17-cell differentiation, Jun Ho Lee for help with the EAE mouse model, Cuong Nguyen and Tonya Wolf of the Flow Cytometry Unit for cell sorting, the staff of the National Institute on Aging animal facility for support and assistance, and Ana Lustig for proofreading the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. J.A and S.G. designed and performed experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. J.K., Y.Z., K.S., G.E.H., W.H.W., R.P.W., and K.G.B. contributed to some of the experiments and data analysis. S.L.S and N.W. directed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. N.W. conceived the research, designed the experiments, and funded the research. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Von Boehmer H. (1992) T cell development and selection in the thymus. Bone Marrow Transplant. 9(Suppl. 1), 46–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hayday A. C., Pennington D. J. (2007) Key factors in the organized chaos of early T cell development. Nat. Immunol. 8, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verbeek S., Izon D., Hofhuis F., Robanus-Maandag E., te Riele H., van de Wetering M., Oosterwegel M., Wilson A., MacDonald H. R., Clevers H. (1995) An HMG-box-containing T-cell factor required for thymocyte differentiation. Nature 374, 70–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zamisch M., Tian L., Grenningloh R., Xiong Y., Wildt K. F., Ehlers M., Ho I. C., Bosselut R. (2009) The transcription factor Ets1 is important for CD4 repression and Runx3 up-regulation during CD8 T cell differentiation in the thymus. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2685–2699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xi H., Kersh G. J. (2004) Early growth response gene 3 regulates thymocyte proliferation during the transition from CD4-CD8- to CD4+CD8+. J. Immunol. 172, 964–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thiel G., Cibelli G. (2002) Regulation of life and death by the zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. J. Cell. Physiol. 193, 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mosmann T. R., Cherwinski H., Bond M. W., Giedlin M. A., Coffman R. L. (2005) Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J. Immunol. 175, 5–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fontenot J. D., Gavin M. A., Rudensky A. Y. (2003) Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 4, 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ivanov I. I., McKenzie B. S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C. E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J. J., Cua D. J., Littman D. R. (2006) The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bettelli E., Oukka M., Kuchroo V. K. (2007) T(H)-17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nat. Immunol. 8, 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Szabo S. J., Kim S. T., Costa G. L., Zhang X., Fathman C. G., Glimcher L. H. (2000) A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell 100, 655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park H., Li Z., Yang X. O., Chang S. H., Nurieva R., Wang Y. H., Wang Y., Hood L., Zhu Z., Tian Q., Dong C. (2005) A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1133–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang F., Meng G., Strober W. (2008) Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1297–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang X. O., Pappu B. P., Nurieva R., Akimzhanov A., Kang H. S., Chung Y., Ma L., Shah B., Panopoulos A. D., Schluns K. S., Watowich S. S., Tian Q., Jetten A. M., Dong C. (2008) T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity 28, 29–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Westendorf A. M., Buer J., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C., Stockinger B. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453, 106–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schraml B. U., Hildner K., Ise W., Lee W. L., Smith W. A., Solomon B., Sahota G., Sim J., Mukasa R., Cemerski S., Hatton R. D., Stormo G. D., Weaver C. T., Russell J. H., Murphy T. L., Murphy K. M. (2009) The AP-1 transcription factor Batf controls T(H)17 differentiation. Nature 460, 405–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brustle A., Heink S., Huber M., Rosenplanter C., Stadelmann C., Yu P., Arpaia E., Mak T. W., Kamradt T., Lohoff M. (2007) The development of inflammatory T(H)-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat. Immunol. 8, 958–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moisan J., Grenningloh R., Bettelli E., Oukka M., Ho I. C. (2007) Ets-1 is a negative regulator of Th17 differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2825–2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhu J., Davidson T. S., Wei G., Jankovic D., Cui K., Schones D. E., Guo L., Zhao K., Shevach E. M., Paul W. E. (2009) Down-regulation of Gfi-1 expression by TGF-beta is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 206, 329–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Langrish C. L., Chen Y., Blumenschein W. M., Mattson J., Basham B., Sedgwick J. D., McClanahan T., Kastelein R. A., Cua D. J. (2005) IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 201, 233–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Komiyama Y., Nakae S., Matsuki T., Nambu A., Ishigame H., Kakuta S., Sudo K., Iwakura Y. (2006) IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 177, 566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martinez G. J., Zhang Z., Reynolds J. M., Tanaka S., Chung Y., Liu T., Robertson E., Lin X., Feng X. H., Dong C. (2010) SMAD2 positively regulates the generation of Th17 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 29039–29043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reynolds J. M., Pappu B. P., Peng J., Martinez G. J., Zhang Y., Chung Y., Ma L., Yang X. O., Nurieva R. I., Tian Q., Dong C. (2010) Toll-like receptor 2 signaling in CD4(+) T lymphocytes promotes T helper 17 responses and regulates the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Immunity 32, 692–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jiang J., Chan Y. S., Loh Y. H., Cai J., Tong G. Q., Lim C. A., Robson P., Zhong S., Ng H. H. (2008) A core Klf circuitry regulates self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McConnell B. B., Ghaleb A. M., Nandan M. O., Yang V. W. (2007) The diverse functions of Kruppel-like factors 4 and 5 in epithelial biology and pathobiology. Bioessays 29, 549–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garrett-Sinha L. A., Eberspaecher H., Seldin M. F., de Crombrugghe B. (1996) A gene for a novel zinc-finger protein expressed in differentiated epithelial cells and transiently in certain mesenchymal cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 31384–31390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen X., Xu H., Yuan P., Fang F., Huss M., Vega V. B., Wong E., Orlov Y. L., Zhang W., Jiang J., Loh Y. H., Yeo H. C., Yeo Z. X., Narang V., Govindarajan K. R., Leong B., Shahab A., Ruan Y., Bourque G., Sung W. K., Clarke N. D., Wei C. L., Ng H. H. (2008) Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell 133, 1106–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klaewsongkram J., Yang Y., Golech S., Katz J., Kaestner K. H., Weng N. P. (2007) Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates B cell number and activation-induced B cell proliferation. J. Immunol. 179, 4679–4684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Katz J. P., Perreault N., Goldstein B. G., Lee C. S., Labosky P. A., Yang V. W., Kaestner K. H. (2002) The zinc-finger transcription factor Klf4 is required for terminal differentiation of goblet cells in the colon. Development 129, 2619–2628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee P. P., Fitzpatrick D. R., Beard C., Jessup H. K., Lehar S., Makar K. W., Perez-Melgosa M., Sweetser M. T., Schlissel M. S., Nguyen S., Cherry S. R., Tsai J. H., Tucker S. M., Weaver W. M., Kelso A., Jaenisch R., Wilson C. B. (2001) A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity 15, 763–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheadle C., Vawter M. P., Freed W. J., Becker K. G. (2003) Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J. Mol. Diagn. 5, 73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Laurence A., Tato C. M., Davidson T. S., Kanno Y., Chen Z., Yao Z., Blank R. B., Meylan F., Siegel R., Hennighausen L., Shevach E. M., O'Shea J. J. (2007) Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity 26, 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou L., Lopes J. E., Chong M. M., Ivanov I. I., Min R., Victora G. D., Shen Y., Du J., Rubtsov Y. P., Rudensky A. Y., Ziegler S. F., Littman D. R. (2008) TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature 453, 236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Araki Y., Fann M., Wersto R., Weng N. P. (2008) Histone acetylation facilitates rapid and robust memory CD8 T cell response through differential expression of effector molecules (eomesodermin and its targets: perforin and granzyme B). J. Immunol. 180, 8102–8108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beeton C., Chandy K. G. (2007) Isolation of mononuclear cells from the central nervous system of rats with EAE. J. Vis. Exp. 10, 527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tabrizifard S., Olaru A., Plotkin J., Fallahi-Sichani M., Livak F., Petrie H. T. (2004) Analysis of transcription factor expression during discrete stages of postnatal thymocyte differentiation. J. Immunol. 173, 1094–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. David-Fung E. S., Butler R., Buzi G., Yui M. A., Diamond R. A., Anderson M. K., Rowen L., Rothenberg E. V. (2009) Transcription factor expression dynamics of early T-lymphocyte specification and commitment. Dev. Biol. 325, 444–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katz J. P., Perreault N., Goldstein B. G., Actman L., McNally S. R., Silberg D. G., Furth E. E., Kaestner K. H. (2005) Loss of Klf4 in mice causes altered proliferation and differentiation and precancerous changes in the adult stomach. Gastroenterology 128, 935–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laky K., Fowlkes B. J. (2007) Presenilins regulate alphabeta T cell development by modulating TCR signaling. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2115–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolfer A., Wilson A., Nemir M., MacDonald H. R., Radtke F. (2002) Inactivation of Notch1 impairs VDJbeta rearrangement and allows pre-TCR-independent survival of early alpha beta lineage thymocytes. Immunity 16, 869–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou M., McPherson L., Feng D., Song A., Dong C., Lyu S. C., Zhou L., Shi X., Ahn Y. T., Wang D., Clayberger C., Krensky A. M. (2007) Kruppel-like transcription factor 13 regulates T lymphocyte survival in vivo. J. Immunol. 178, 5496–5504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shields J. M., Yang V. W. (1998) Identification of the DNA sequence that interacts with the gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 796–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tsukiyama T., Ishida N., Shirane M., Minamishima Y. A., Hatakeyama S., Kitagawa M., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. (2001) Down-regulation of p27(Kip1) expression is required for development and function of T cells. J. Immunol. 166, 304–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sun Z., Unutmaz D., Zou Y. R., Sunshine M. J., Pierani A., Brenner-Morton S., Mebius R. E., Littman D. R. (2000) Requirement for RORgamma in thymocyte survival and lymphoid organ development. Science 288, 2369–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kurebayashi S., Ueda E., Sakaue M., Patel D. D., Medvedev A., Zhang F., Jetten A. M. (2000) Retinoid-related orphan receptor gamma (RORgamma) is essential for lymphoid organogenesis and controls apoptosis during thymopoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 10132–10137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carlson C. M., Endrizzi B. T., Wu J., Ding X., Weinreich M. A., Walsh E. R., Wani M. A., Lingrel J. B., Hogquist K. A., Jameson S. C. (2006) Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature 442, 299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sebzda E., Zou Z., Lee J. S., Wang T., Kahn M. L. (2008) Transcription factor KLF2 regulates the migration of naive T cells by restricting chemokine receptor expression patterns. Nat. Immunol. 9, 292–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wei D., Kanai M., Jia Z., Le X., Xie K. (2008) Kruppel-like factor 4 induces p27Kip1 expression in and suppresses the growth and metastasis of human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 4631–4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rowland B. D., Bernards R., Peeper D. S. (2005) The KLF4 tumour suppressor is a transcriptional repressor of p53 that acts as a context-dependent oncogene. Nat. Cell Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lebson L., Gocke A., Rosenzweig J., Alder J., Civin C., Calabresi P. A., Whartenby K. A. (2010) Cutting edge: The transcription factor Kruppel-like factor 4 regulates the differentiation of Th17 cells independently of RORgammat. J. Immunol. 185, 7161–7164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.