Abstract

This Letter describes a chemical lead optimization campaign directed at VU0238429, the first M5-preferring positive allosteric modulator (PAM), discovered through analog work around VU0119498, a pan Gq mAChR M1, M3, M5 PAM. An iterative library synthesis approach delivered the first selective M5 PAM (no activity at M1–M4 @ 30 μM), and an important tool compound to study the role of M5 in the CNS.

The muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) are members of the family A G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and include five subtypes denoted M1–M5. M1, M3 and M5 couple to Gq and activate phospholipase C, whereas M2 and M4 couple to Gi/o and associated effector systems. All five of the mAChRs are known to play critical roles in multiple basic physiological processes.1–3 As such cholinergic agents that activate or inhibit one or more subtypes have found success both preclinically and clinically for a number of peripheral and CNS pathologies.3,4 Within the mAChRs, a major challenge has been a lack of subtype selective ligands to study the specific contribution of discrete mAChRs in various disease states. To address this limitation, we have focused on targeting allosteric sites on mAChRs as a means to develop subtype selective small molecules, both allosteric agonists and positive allosteric modulators (PAMs).5–11

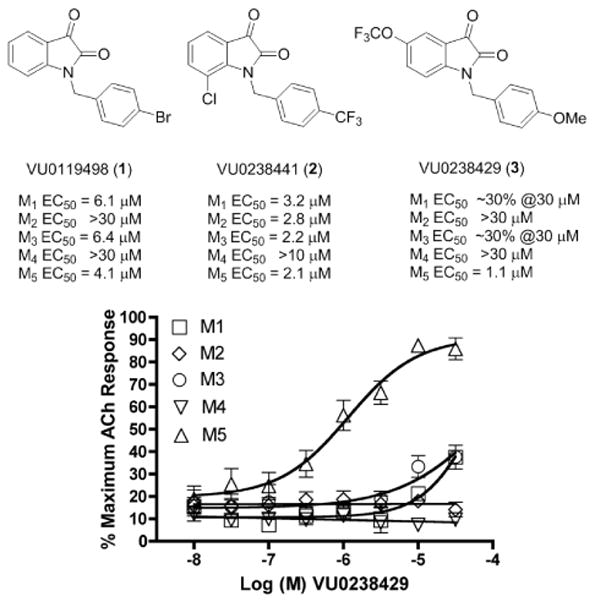

From a functional cell-based high-throughput screen (HTS) to identify M1 positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) we identified VU0119498, an M1, M3, M5 PAM (Fig. 1). This was a unique hit from the screen, as it was not selective for M1, but the first example of a pan-Gq mAChR PAM, devoid of activity at the Gi/o-coupled M2 and M4.

Figure 1.

HTS hit VU0119498, a pan Gq mAChR M1, M3, M5 PAM, VU0238441, a pan mAChR PAM and VU0238429, a highly M5-preferring PAM. Data represent means of at least three independent determinations with similar results using mobilization of intracellular calcium as a functional readout for receptor activation M1–M5 CHO cells (M2 and M4 cells co-transfected with Gqi5).

Relative to M1–M4, little is known about the precise role(s) of M5 in the CNS. However, localization data and studies using M5-knockout (KO) mice suggest that M5 activation is highly important to regulation of central dopaminergic pathways and to ACh-induced cerebrovasodilation. In light of these findings, drugs targeting M5 may have therapeutic potential for numerous CNS disorders, including cerebrovascular dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Schizophrenia2,4,12–14. Historically, lack of selective pharmacological tools available to confirm the putative role(s) of M5 has seriously hindered progress in this area.

Starting from a pan M1, M3, M5 PAM, VU0119498, we felt it may be possible to maintain M5 PAM activity and dial out M1 and M3 PAM activity through a chemical lead optimization campaign. In a recent Letter,15 we reported on the discovery and characterization of VU0238429, the first M5-preferring PAM. At 30 μM, VU0238429 displayed a 14-fold leftward shift of the ACh concentration-response-curve (CRC), increased ACh affinity for M5 by ~11-fold and did not displace [3H]-NMS from binding to M515. While this was a major advance in the field, we hoped to develop a truly M5 selective PAM to dissect the role of M5 in the CNS. In this Letter, we describe an iterative parallel synthesis approach16 for the further optimization of VU0238429, and the discovery of M5 PAMs with unprecedented mAChR selectivity (≫30 μM vs. M1–M4).

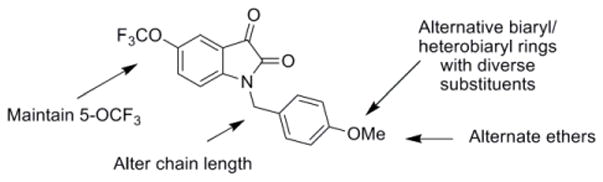

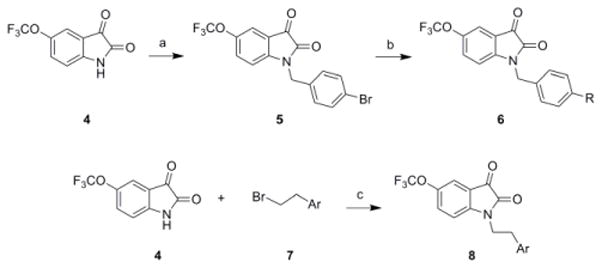

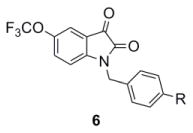

Our optimization strategy is outlined in Figure 2, and as SAR with allosteric ligands is often shallow,5,6,17 we employed an iterative parallel synthesis approach.16 From our earlier work, the 5-OCF3 group was essential for M5-preferring activity, so this moiety was maintained.15 Libraries were prepared according to Scheme 1, wherein commercial 5-(trifluoromethoxy)indoline-2,3-dione 4 was alkylated with p-bromobenzylbromide to deliver key intermediate 5. An 11-member Suzuki library was then prepared to explore the effect of introduction of biaryl and heterobiaryl motifs into VU0238429 providing analogs 6. In parallel, 4 was alkylated with functionalized phenethyl bromides 7 to probe the effect of chain homologation in analogs 8. Compound libraries were then triaged by a single point (10 μM) screen for their ability to potentiate an EC20 of ACh in M5-CHO cells (Fig. 3).15 Based on this screen, select compounds were assayed in 8-point CRCs based on their potentiation efficacy.

Figure 2.

Optimization strategy for VU0238429 (1), a highly M5-preferring PAM.

Scheme 1.

a) p-bromobenzylbromide, K2CO3, KI, ACN, rt, 16 h (99%); b) RB(OH)2, Pd(Pt-Bu3)2, Cs2CO3, THF:H2O, mw, 120 °C, 20 min (10–90%); c) K2CO3, KI, ACN, rt, 16 h (50–90%).

Figure 3.

ACh EC20 triage screen of libraries of analogs 6 and 8 at 10 μM in M5 CHO cells by intracellular calcium mobilization assay. Data represent means from at least three independent determinations with similar results.

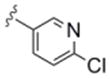

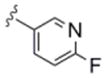

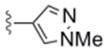

In general, chain homologation in analogs 8 proved unsuccessful as potency was compromised despite retention of PAM efficacy at higher concentrations. For example 8a, the direct phenethyl analog of VU0238429 possessed an M5 EC50 of 4.9 μM and 80% ACh maximum response (data not shown). Biaryl and heterobiaryl analogs 6 proved far more productive, affording a number of M5 PAMs with high selectivity versus M1 (>30 uM EC50s) and low micromolar M5 EC50s (Table 1). All other analogs 6 possessed M5 EC50s >10 μM. In general, both 5- (6b and 6e) and 6-membered heterocycles (6c and 6d) were tolerated as were simple phenyl (6a) and substituted phenyl (6f). Potency was virtually identical for all of these analogs (M5 EC50s 2.7 μM to 4.8 μM) with similar ACh Max values (70–85%). Shallow SAR was again noted with compounds either being active in this potency range or inactive as M5 PAMs.

Table 1.

Structures and activities of analogs 6.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | VU Number | R | hM5 EC50 (μM)a | % ACh Maxa |

| 6a | 0365114 |

|

2.7 | 85 |

| 6b | 0365117 |

|

2.8 | 85 |

| 6c | 0365118 |

|

4.8 | 85 |

| 6d | 0365121 |

|

3.6 | 80 |

| 6e | 0365123 |

|

3.3 | 85 |

| 6f | 0365116 |

|

3.9 | 70 |

Average of at least three independent determinations. All compounds M1 EC50 > 30 μM.

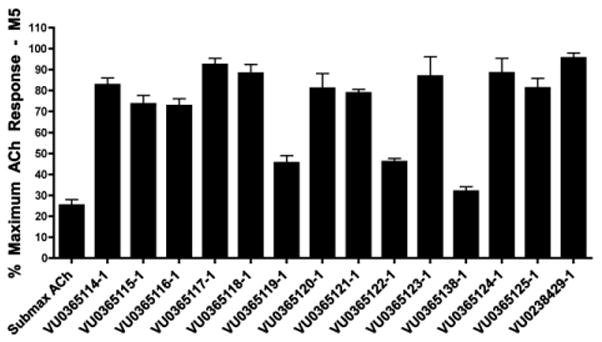

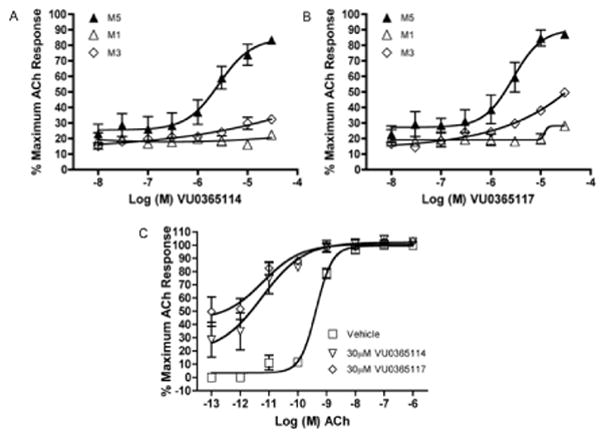

Analogs 6a (VU0365114) and 6b (VU0365117) were selected for additional follow-up. Figure 4 depicts Gq mAChR (M1, M3 and M5) CRCs for 6a and 6b. Note 6a possesses improved M5 selectivity versus VU0238429 (3), with only modest activation of M3 at 30 μM. Both analogs 6a and 6b elicit significant leftward shifts (>50-fold) of the ACh CRC, as compared to the 14-fold shift of VU0238429 (3). As seen with the M1 PAM BQCA18–20 and other ago-potentiators for class C GPCRs,21–23 figure 4C indicates moderate intrinsic allosteric agonism at 30 μM.

Figure 4.

A) CRCs for VU0365114 (6a) at M1, M3 and M5 CHO cells; B) CRCs for VU0365117 (6b) at M1, M3 and M5 CHO cells; C) M5 Fold-shift experiments of the ACh CRC with 30 μM of either 6a or 6b (both >50x) in M5 CHO cells. Data represent means from at least three independent determinations with similar results.

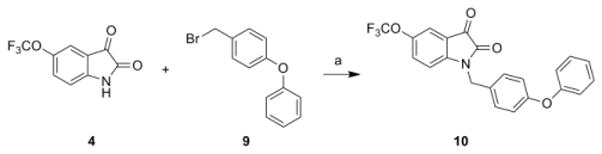

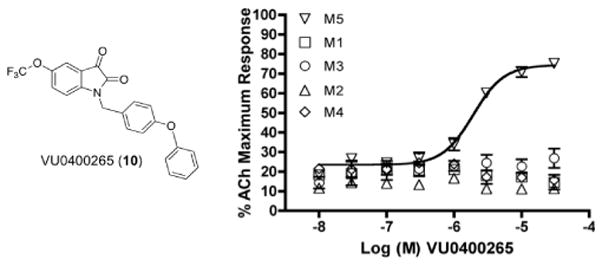

Encouraged by the potency and mAChR selectivity of VU0365114 (6a) and VU0238429 (3), we synthesized (Scheme 2) a hybrid analog possessing a biphenyl ether moiety, VU0400265 (10). VU0400265 possessed an M5 EC50 of 1.9 μM with a 75% ACh Max. Importantly, VU0400265 was completely selective versus M1–M4, affording no elevation of an ACh EC20 at M1–M4 at 30 μM (Fig. 5). Notably, VU0400265 (10) represents the most selective M5 PAM described to date; however, unlike 6a and 6b, analog 10 only afforded a ~5-fold shift of the ACh CRC at 30 μM.

Scheme 2.

a) K2CO3, KI, ACN, mw, 160°C, 10 min (68%).

Figure 5.

CRCs for VU0400265 (10) at M1, M2, M3, M4 and M5 CHO cells (EC50 = 1.9 μM) with a submaximal (~EC20) of ACh. VU0400265 (10) is the most selective M5 PAM reported to date. Data represent means from at least three independent determinations with similar results (M2 and M4 cells co-transfected with Gqi5).

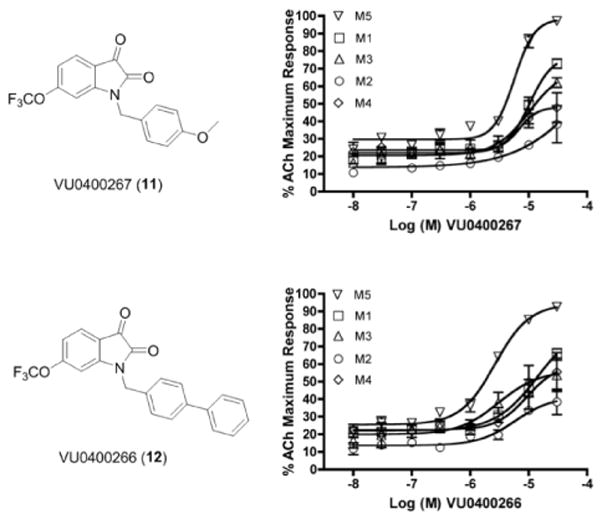

Efforts next centered on maintaining mAChR selectivity and M5 potency, while attempting to improve fold-shift. Subtle structural changes have been shown in this series to have dramatic effects on potency, selectivity and fold-shift. Therefore, we next explored the effect of moving the 5-OCF3 moiety to the 6-position of the isatin core. Following the route in Scheme 1, we quickly prepared the 6-OCF3 analogs 11 and 12 of our initial M5-preferring PAM VU0119498 (3) and the biphenyl congener VU0365114 (6a), respectively. Interestingly, M5 potency was relatively maintained (M5 EC50s of 5.7 μM and 2.7 μM, for 11 (VU0400267) and 12 (VU0400266), respectively); however, both afforded ~95% of ACh Max, suggesting the fold-shift might be improved with this modification. Quite unexpectedly, mAChR selectivity was lost (Fig. 6), once again highlighting the difficulty in developing SAR for allosteric ligands5,6,17. A 6-OCF3 congener of VU0400265 (10) provided similar erosion in mAChR selectivity. Due to the loss in M5 selectivity, ACh fold-shift experiments were not performed.

Figure 6.

CRCs for VU0400267 (11) and VU0400266 (12) at M1, M2, M3, M4 and M5 CHO Cells with a submaximal (EC20) of ACh. Data represent means from at least three independent determinations with similar results (M2 and M4 cells co-transfected with Gqi5).

All of these analogs displayed moderate to poor PK in rats with limited brain exposure (AUCBrain/AUCPlasma ~0.25), presumably due to the bis-carbonyl of the isatin moiety. However, these are important tools to study M5 function in cells, in electrophysiology and by icv injection. We did not examine the brain exposure when a DMSO-containing vehicle was employed, and this may improve brain levels.21–22

Thus, further optimization of an M5-preferring PAM VU0238249 (3), derived from a pan Gq mAChR PAM, provided two highly selective M5 PAMs - VU0365114 (6a) and VU0400265 (10). While VU0400265 (10) is the most selective M5 PAM reported to date, 6a is highly selective for M5 and displays a >50-fold shift of the ACh CRC. These selective tool compounds will finally allow researchers to dissect the role of M5 in the CNS, the one mAChR that has remained a mystery due to the lack of tool compounds. Since selective M5 PAMs could be obtained from a pan Gq PAM lead, we are currently optimizing VU0119498 to provide highly selective M1 PAMs as well as M3 PAMs. Efforts in this arena are in progress with exciting results, which will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NIMH (1RO1 MH082867), NIH, the MLPCN (1U54 MH084659) and the Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG-07-57131) for support of our Program in the development of subtype selective allosteric ligands of mAChRs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Bonner TI, Buckley NJ, Young AC, Brann MR. Science. 1987;237:527–532. doi: 10.1126/science.3037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner TI, Young AC, Brann MR, Buckley NJ. Neuron. 1988;1:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wess J. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:423–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langmead CJ, Watson J, Reavill C. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conn PJ, Jones C, Lindsley CW. Trends in Pharm Sci. 2009;30:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Nat Rev Durg Disc. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady A, Jones CK, Bridges TM, Kennedy PJ, Thompson AD, Breininger ML, Gentry PR, Yin H, Jadhav SB, Shirey J, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J Pharm & Exp Ther. 2008;327:941–952. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy JP, Bridges TM, Gentry PR, Brogan JT, Brady AE, Shirey JK, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Chem Med Chem. 2009;4:1600–1607. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Jones CK, Brady AE, Davis AA, Xiang Z, Bubser M, Tantawy MN, Kane A, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Bradley SR, Peterson T, Baldwin RM, Kessler R, Deutch A, Lah JL, Levey AI, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J Neurosci. 2008;28(41):10422–10433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bridges TM, Brady AE, Kennedy JP, Daniels NR, Miller NR, Kim K, Breininger ML, Gentry PR, Brogan JT, Jones JK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5439–5442. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Miller NR, Daniels NR, Bridges TM, Brady AE, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5443–5446. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Luo Q, Brady AE, Shirey JK, Rodriguez AL, Bridges TM, Williams R, Days E, Nalywajko NT, Austin C, Williams M, Xiang Y, Orton D, Brown HA, Kim K, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn PJ. Mol Pharm. 2009;75(3):577–588. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lebois EP, Bridges TM, Dawson ES, Kennedy Jp, Xiang Z, Jadhav SB, Yin H, Meiler J, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Weaver CD, Lindsley CW. ACS Chemical Neurosci. doi: 10.1021/cn900003h. ARTICLE ASAP, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada M, Lamping KG, Duttaroy A, Zhang W, Cui Y, Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC, Deng C, Faraci FM, Wess J. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:14096–14101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251542998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Araya R, Noguchi T, Yuhki M, Kitamura N, Higuchi M, Saido TC, Seki K, Itohara S, Kawano M, Tanemura K, Takashima A, Yamada K, Kondoh Y, Kanno I, Wess J, Yamada M. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:721–733. doi: 10.1038/nrd2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridges TM, Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Jones JK, Jadhav SB, Gentry PR, Weaver CD, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3445–3448. doi: 10.1021/jm900286j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy JP, Williams L, Bridges TM, Daniels RN, Weaver D, Lindsley CW. J Comb Chem. 2008;10:345–354. doi: 10.1021/cc700187t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conn PJ, Lindsley CW, Jones C. Trends in Pharm Sci. 2009;30:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma L, Seager M, Wittman M, Bickel N, Burno M, Jones K, Graufelds VK, Xu G, Pearson M, McCampbell A, Gaspar R, Shughrue P, Danzinger A, Regan C, Garson S, Doran S, Kreatsoulas C, Veng L, Lindsley CW, Shipe W, Kuduk S, Jacobson M, Sur C, Kinney G, Seabrook GR, Ray WJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15950–15955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900903106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady AE, Shirey JK, Jones PJ, Davis AA, Bridges TM, Jadhav SB, Menon U, Christain EP, Doherty JJ, Quirk MC, Snyder DH, Levey AI, Watson ML, Nicolle MM, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J Neurosci. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang FV, Shipe WD, Bunda JL, Nolt MB, Wisnoski DD, Zhao Z, Barrow JC, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittman M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Hartman GD, Lindsley CW. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.100. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindsley CW, Wisnoski DD, Leister WH, O’Brien JA, Lemiare W, Williams DL, Jr, Burno M, Sur C, Kinney GG, Pettibone DJ, iller PR, Smith S, Duggan ME, Hartman GD, Conn PJ, Huff JR. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5825–5828. doi: 10.1021/jm049400d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinney GG, O’Brien Lemaire W, Burno M’Bickel DJ, Clements MK, Wisnoski DD, Lindsley CW, Tiller PR, Smith S, Jacobson MA, Sur C, Duggan ME, Pettibone DJ, Williams DW., Jr J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2005;313(1):199–208. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engers DW, Rodriguez AL, Oluwatola O, Hammond AS, Venable DF, Williams R, Sulikowski GA, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. Chem Med Chem. 2009;4:505–511. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]