Abstract

Throughout Amazonia, overfishing has decimated populations of fruit-eating fishes, especially the large-bodied characid, Colossoma macropomum. During lengthy annual floods, frugivorous fishes enter vast Amazonian floodplains, consume massive quantities of fallen fruits and egest viable seeds. Many tree and liana species are clearly specialized for icthyochory, and seed dispersal by fish may be crucial for the maintenance of Amazonian wetland forests. Unlike frugivorous mammals and birds, little is known about seed dispersal effectiveness of fishes. Extensive mobility of frugivorous fish could result in extremely effective, multi-directional, long-distance seed dispersal. Over three annual flood seasons, we tracked fine-scale movement patterns and habitat use of wild Colossoma, and seed retention in the digestive tracts of captive individuals. Our mechanistic model predicts that Colossoma disperses seeds extremely long distances to favourable habitats. Modelled mean dispersal distances of 337–552 m and maximum of 5495 m are among the longest ever reported. At least 5 per cent of seeds are predicted to disperse 1700–2110 m, farther than dispersal by almost all other frugivores reported in the literature. Additionally, seed dispersal distances increased with fish size, but overfishing has biased Colossoma populations to smaller individuals. Thus, overexploitation probably disrupts an ancient coevolutionary relationship between Colossoma and Amazonian plants.

Keywords: dispersal kernel, Colossoma macropomum, frugivorous fish, movement ecology, radiotelemetry, seed dispersal

1. Introduction

Long-distance seed dispersal enhances regional population persistence and gene flow between distant plant populations, enables range expansion and colonization of remote patches, and may facilitate species coexistence [1–5]. It is, however, difficult to quantify this critical process as long-distance dispersal events are thought to be rare [1]. Nevertheless, if fruit consumption coincides with periods of high mobility, frugivores may routinely disperse seeds long distances. Unlike frugivorous birds and mammals [1,6–8], we know little about the role of fruit-eating fishes as vectors of long-distance seed dispersal [9,10].

During annual floods that can exceed half a year in duration, frugivorous fishes consume fruits that fall into the water in Amazonian floodplain habitats, which occupy an area of more than 250 000 km2 [9,11–16]. Fruiting generally coincides with flooding and seeds are highly adapted to dispersal by water and/or fishes [9,17–21]. Massive quantities of viable seeds have been encountered in the digestive tracts of fruit-eating fishes and fish-mediated seed dispersal may be crucial for plant regeneration in flooded habitats [9–11,17,22,23]. Despite the extensive mobility of fruit-eating fish [10], no study to date has assessed whether fish provide long-distance seed dispersal to habitats suitable for seedling recruitment.

Animals have complex movement patterns in heterogeneous landscapes, and frugivores clearly disperse seeds to habitats that differ in quality from the perspective of the seed [6,24–28]. Nevertheless, models of seed dispersal distances do not account for the loss of seeds to inappropriate habitats, despite the often stringent conditions necessary for germination and recruitment to later life-history stages [24,29,30]. In wetlands, effective dispersers (sensu [26]) must deposit seeds in seasonally flooded habitats to prevent their demise in permanent bodies of water, such as rivers and lakes.

Colossoma macropomum Cuvier (Characidae; hereafter: Colossoma) is widely distributed throughout tropical South America and is an extremely commercially important fish [9,13,31,32]: in the 1970s, 36–40 per cent of the fish for sale at the major Manaus (Brazil) fish market were individuals of this one species [31,32]. Overfishing has reduced population sizes by 90 per cent in some areas over the past several decades, decreased individual fish size and altered the age structure of populations [31,33,34]. Colossoma individuals consume enormous numbers of seeds of a diverse array of plant species across the range of the species [9]. For example, we discovered nearly 700 000 intact seeds from 22 tree and liana species in the digestive contents of 230 Colossoma individuals, representing up to 21 per cent of the flora fruiting during the flooded season at our field site in Peru [11].

Our objective in the present study was to test the hypothesis that Colossoma is an effective vector of long-distance seed dispersal; this study is timely owing to the declining populations of this and other formerly abundant species of frugivorous fishes. We integrate data on the movement patterns, habitat preferences and gut retention times of Colossoma individuals over three flood seasons to generate a spatially explicit mechanistic model of seed dispersal for five species of trees and lianas. We compare seed dispersal curves generated by Colossoma with those produced by 11 other animal dispersers, based on a review of the literature. Finally, we investigate how seed dispersal distance by Colossma varies with fish size and we make inferences on how seed dispersal effectiveness is likely to be influenced by overfishing in the Amazon.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study site and focal species

We conducted this study during three flood seasons (2004–2006) in Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve (5°21′ S; 74°30′ W), a 21 924 km2 area in northeastern Peru [11,35]. Approximately 90 per cent of this reserve consists of floodplain forests, other wetlands, rivers and lakes; flooding occurs annually from January to June and floodwaters can reach up to 6 m deep [11,35]. Colossoma is among the largest species of fishes in tropical South America, and can weigh 20–30 kg and measure more than 1 m in length [31,33]. Colossoma is common at our field site primarily because fishing pressure is low within the reserve.

(b). Radiotelemetry

To study fine-scale spatial movement patterns, we inserted radio transmitters in the opercula of 24 wild sub-adult and adult Colossoma over three flood seasons (2004: n = 5; 2005: n = 7; 2006: n = 12) and released fish at the point of capture. In 2005 and 2006, individuals were weighed and standard length was measured prior to insertion of the radio transmitter; measuring the fish and inserting the transmitter took less than 3–4 min, during which time, we gently moved water over the gills to minimize stress to the fish. The flat transmitter (15.5 × 50 mm, Advanced Telemetry Systems) was attached with monofilament line to the outer operculum to diminish interference with the gills [10] and to avoid bacterial infection that could arise from surgical implantation. The transmitters weighed less than 1 per cent of the average body mass of Colossoma individuals included in this study (transmitter weight in air = 17 g; Colossoma weight in air: average ± s.d.: 1790.8 ± 815.4 g; range 750–2900 g; see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1 for individual weights), and should therefore not have interfered with fish movement [36]. Low-frequency (40 mHz) coded transmitters were equipped with a 30 day battery [37,38]. We followed radiotagged individuals in canoes to reduce behavioural disruption that could have occurred from boats with outboard motors.

Every 30 min from 07.00 to 17.00, we located fish by triangulating radio signals from two to four positions (i.e. bearings), recorded their coordinates with a hand-held global positioning system (GPS) unit [37] and noted the habitat from which the radio signal originated. To calculate error around bearings, we took three to four bearings at three or more locations during each follow. We estimated the errors for all other bearings for each individual fish using standard deviations calculated for these locations in the program Locate III (Pacer Computing, Tatamagouche, NS, Canada; http://www.locateiii.com/), and incorporated error into our simulation models (see below). Triangulation was not used during the pilot 2004 season when we were perfecting the technique for following fish in dense flooded forests; instead, locations were determined by approaching the signal until it was strong enough that the fish was likely to be within 15 m and then recording a GPS location. Telemetry accuracy was also tested by attaching a radiotransmitter to fishing line, and hiding it in the water up to 500 m from the telemetry crew. In all cases (n = 5), the exact location of the transmitter was determined, and the device was retrieved.

When we could not locate a fish, we searched extensively for 2 days before capturing a new individual for telemetry. Radiotagged individuals were followed an average of 8.5 ± 6.5 days (mean ± s.d.; range: 2 h–29.5 days; see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1) before being lost. To date, no published study presents data on the fine-scale movements of fruit-eating fish [10].

(c). Gut retention times

To gather data on gut-passage rates, we fed known quantities of five species of seeds to captive Colossoma individuals housed in individual tanks at the Instituto para la Investigación de la Amazonia Peruana in 2005 and 2006 (IIAP, Institute for the Study of the Peruvian Amazon; n = 5 in 2005, n = 3–5 adults and 4–5 juveniles, see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S2 for more detailed information): Duroia duckei (Rubiaceae; tree), Cecropia latiloba (Urticaceae; pioneer tree), Cayaponia cruegeri (2005 only; liana) and Cayaponia tubulosa (2006 only; Cucurbitaceae; liana), and Annona muricata (2006 only; Annonaceae; tree) [11]. Seeds of these five species are a major component of the diet of Colossoma, and germinate rapidly after defecation [11].

Hourly, we recorded the number of seeds defecated by each fish, and removed all defecated seeds. Gut retention times were longer than expected (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix figure S1); in 2005, we only monitored captive Colossoma during the day, but in 2006 we monitored them by day and night. From the 2005 data, we cannot accurately determine the time that fish defecated seeds at night, so we assumed conservatively that all seeds found in the tank each morning were defecated at a constant rate the previous night. We fed each fish 4–200 seeds from each seed species (depending on the size of the seed), replicated each feeding trial two to three times per fish, and calculated the proportion of seeds defecated during each hour interval (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S2 for sample sizes, duration of experiment and number of intact seeds defecated). Fish were fed only one species of seed during each feeding trial. Fish were monitored until they no longer defecated intact seeds, which ranged from 2 to 12 days depending on the species of seed; fish ingested intact 92.4 per cent of the seeds they were fed (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S2). During these trials, fish were supplemented with an extruded diet, consisting of 25 per cent protein, designed to meet their dietary needs [11]. Further details about these feeding trials are presented elsewhere, along with results of experiments in which we compared the germination rates of seeds defecated by fish in these trials with seeds in several control treatments [11].

(d). Simulation model

We developed a spatially explicit, individual-based simulation model in C (Microsoft Visual Studio 2005; code available in the electronic supplementary material) that integrates data on movement patterns and habitat affinities of wild fish, and the gut retention times of captive fish. We generated dispersal kernels for the five tree and liana species whose seeds we fed to Colossoma: D. duckei, Cecropia latiloba, Cayaponia cruegeri and C. tubulosa, and A. muricata [11]. The input data for the model are telemetry locations from fish and gut retention times for the different species of seeds. Telemetry locations include a time stamp and a habitat classification. The distributions of seed dispersal distances (i.e. the dispersal kernels) were modelled separately for each species.

The distance a seed disperses is a function of time in the digestive tract and distance the fish moves over that interval from the point of origin. From a random forest or savannah starting location from the fish telemetry data with time stamp t, the model selects a random deviate T from the cumulative distribution of gut retention times to follow the fish. The model then tracks the fish until time stamp t + T in the telemetry data is reached. If the end of the fish's telemetry data is reached before elapsed time T is reached, the model starts over with a new fish and starting location. Telemetry measurement error associated with each telemetry location is added to locations at time t and t + T and the distance between these two points is calculated to determine the dispersal distance of the seed. The model flagged dispersal to permanent bodies of water. For each of the five seed species, the model was run for 100 000 iterations to characterize the dispersal shadow for that species. We determined median and 95th percentile dispersal distances for each seed species.

(e). Individual-level variation in movement patterns

Individual fish vary in their movement patterns, with some fish moving great distances and some apparently moving only locally. To quantify effect of individual variability in movements, we ran the model for 100 000 iterations separately for each of 15 fish that accumulated at least 100 h of observation with at least 100 individual locations. Gut retention times were from the full Cecropia dataset. The effect of individual variation in movements was quantified as the standard error of the median and 95th percentile dispersal distances. We tested the hypothesis that dispersal distances increase with fish size (Proc GLM, SAS v. 9.2).

(f). Comparison with other dispersers

We compiled data from studies that quantify movement patterns and gut retention times to compare seed dispersal by Colossoma with dispersal by other frugivores. We used data from seven studies of large-bodied frugivores [7,8,39–43], one classic study of two passerine and one piciform bird species [44], and one study of European jays that accounted for habitat [28] (for additional details on data from these studies, see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S3). We have included dispersal data from the longest distance seed dispersers studied to date: African hornbills [7] and Asian elephants [8]. We gathered data on the proportion of seeds dispersed to different distance classes using the program Engauge Digitizer (v. 4.1; http://digitizer.sourceforge.net). Data for spider monkeys [39] were supplied by S. Russo. When dispersal curves were given for more than one seed species, or congeneric species of frugivores (e.g. two species of hornbills [7]), we calculated average dispersal distances. We include average dispersal curves from this study and curves from seeds with the minimum (Cayaponia cruegeri) and maximum (Cayaponia tubulosa) gut retention times.

3. Results

(a). Radiotelemetry

We followed 24 radiotagged Colossoma individuals for an average of 8.5 days (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1), which resulted in 1751 h of continuous fine-scale movement data. These highly mobile fish moved at a rate of 50.7 ± 26.7 m h–1 (average ± s.d.; summary telemetry data in the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S1). These fish moved up to 5.9 km away from the location at the beginning of the telemetry follow, suggesting that they could be vectors of long-distance seed dispersal.

(b). Gut retention

Colossoma individuals retained seeds in their digestive tracts for long periods of time, up to 212 h (electronic supplementary material, figure S1 and appendix table S4). Gut retention differed significantly by seed species (Cox Proportional Hazards Model; χ2 = 404.7, d.f. = 4; p < 0.0001). Average gut retention time ranged from 34.7 h (±0.97 h s.e.) for seeds of Cayaponia cruegeri to 147.3 h (±10.3 h s.e.) for seeds of Cayaponia tubulosa; across species of seeds, gut retention time averaged 74.0 h (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S4).

(c). Simulation model

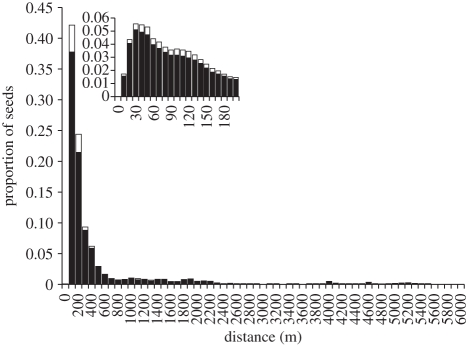

Our seed dispersal models were multimodal and had fat tails, i.e. dispersal distances did not drop sharply to zero as would be expected based on short-distance movements. These models predict long-distance seed dispersal for all species of seeds (figure 1 and the electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Dispersal to floodplain forests and savannahs (suitable habitat) was substantially greater than dispersal to permanent bodies of water (unsuitable habitat). Only 7.8–9.2% of the seeds in our simulation models were deposited in rivers or lakes (table 1).

Figure 1.

Dispersal of Cecropia latiloba seeds by Colossoma to sites suitable for germination (solid bars) and unsuitable due to permanent standing water (open bars). Dispersal of the other four species of seeds produced similar patterns (electronic supplementary material, appendix figure S2). The inset panel indicates dispersal within 200 m.

Table 1.

Predicted seed dispersal distances for the five Amazonian tree and liana species modelled in this study. These values apply only to seeds dispersed into suitable habitats (flooded forests and savannahs). The final column indicates seed loss to permanent bodies of water.

| species of seed | mean dispersal distance (m) | median dispersal distance (m) | 95th percentile (m) | maximum dispersal distance (m) | seeds deposited in inhospitable habitat (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. muricata | 422.3 | 146.8 | 1826.9 | 5412.7 | 8.5 |

| Cayaponia cruegeri | 337.3 | 107.4 | 1714.7 | 5363.9 | 9.2 |

| Cayaponia tubulosa | 552.5 | 205.3 | 2114.4 | 5486.2 | 7.8 |

| Cecropia latiloba | 380.7 | 125.6 | 1800.4 | 5436.0 | 9.2 |

| D. duckei | 341.4 | 114.6 | 1707.5 | 5494.8 | 9.0 |

Excluding seeds lost to sink habitats, our models predicted that Colossoma dispersed seeds a mean distance of 337–552 m and 5 per cent of seeds were predicted to disperse more than 1707–2114 m, depending on plant species (table 1). All dispersal curves exhibited one peak representative of local seed dispersal within approximately 600 m of the origin (i.e. the maternal plant), and additional peaks representative of interpatch movement: from approximately 600 to 2700 m, and from approximately 4000 to 5500 m.

(d). Individual variation in gut retention times and movement patterns

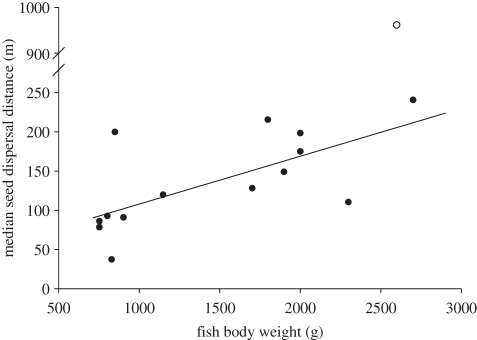

We found substantial variation in estimated seed dispersal distances due to individual differences in movement patterns (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix table S5), indicating that seed dispersal distances may vary with inherent properties of the individual, such as size and age. Larger fish had significantly greater median seed dispersal distances (excluding the potential outlier: β = 0.06 ± 0.02; F1,12 = 9.87, p = 0.0085, R2 = 45.1%; figure 2). Similarly, we detected a suggestive trend that long-distance dispersal (95th% percentile dispersal) may also increase with fish weight (F1,13 = 3.47, p = 0.085, R2 = 21%).

Figure 2.

Median seed dispersal distances increased as a function of fish body weight. Note the break in the y-axis to accommodate the outlier (fish number 994; open circle). The predicted relationship displayed is based on the slope of the regression without the possible outlier (slope: 0.06 ± 0.02 m g–1, F1,12 = 9.87, p = 0.0085, R2 = 45.1%).

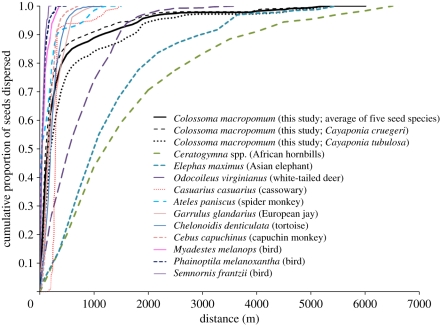

(e). Comparison with other frugivores

As with other well-known large frugivores, Colossoma dispersed the majority of seeds within 200 m of the maternal plant (figure 3). However, the long gut retention times, in concert with high mobility, resulted in a fat tail, and estimated maximum dispersal distances were similar to those produced by African hornbills [7] and Asian elephants [8], and exceeded those of white-tailed deer [40] (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative seed dispersal curves generated by Colossoma macropomum (this study) and 11 other seed dispersers (see the electronic supplementary material, table S3 for information about these studies). We present Colossoma dispersal curves averaged over all seed species, as well as the maximum (Cayaponia tubulosa) and minimum (Cayaponia cruegeri) curves.

4. Discussion

Enhanced germination following defecation [11] in conjunction with long-distance movements, affinity for habitats favourable for germination and long gut retention times translated into very effective long-distance seed dispersal by Colossoma (figure 1). Modelled dispersal distances greatly exceeded 100 m, which has been defined as ‘long distance’, [5] (table 1). Indeed, seed dispersal by Colossoma surpassed the extent of dispersal provided by most abiotic and biotic vectors and rivaled the maximum dispersal distances produced by the longest distance seed dispersers studied to date: African hornbills [7] and Asian elephants [8] (figures 1 and 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S2 and table S3).

Colossoma achieved long-distance seed dispersal via a combination of long gut retention times and long-distance movements between patches of flooded habitats. Whereas gut retention times in birds tend to be short (from minutes to hours) [44,45], Colossoma had very long retention times for seeds, on par with the 152–157 h retention of Cecropia seeds by a Doradidae catfish [46]. Gut retention time varied significantly as a function of plant species (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) and strongly influenced seed dispersal distance. For example, Cayaponia cruegeri seeds had the shortest gut retention time, and Cayaponia tubulosa seeds had the longest gut retention time. This difference resulted in estimated median dispersal distances of Cayaponia tubulosa (the slow species) being twice as far as Cayaponia cruegeri (the fast species; table 1). In contrast, African hornbills [7] achieved long-distance dispersal of seeds via frequent long-distance movements but short gut retention times; hence, interspecific variation in gut retention times of seeds is probably less important for species being dispersed by birds than by fish or mammals, which typically have longer gut retention times (references in the electronic supplementary material, table S3).

Our models predict minimal seed loss to permanent bodies of water as Colossoma individuals spent the majority of their time in flooded forests and savannahs during the flooded season. This activity pattern is congruent with Saint-Paul et al. [47] who captured more Colossoma in floodplain habitats than rivers, despite greater sampling effort in rivers. In heterogeneous landscapes, mechanistic models of seed dispersal need to account for the loss of seeds to habitats that are unsuitable for germination and seedling growth. Abiotic vectors, such as wind, disperse seeds indiscriminately across the landscape, which results in large numbers of seeds landing in inappropriate sites [3]. In contrast, frugivores have complex behavioural patterns and often exhibit strong habitat affinities [6,25], which may increase the probability of seedling establishment. The preference of Colossoma for floodplain forests and savannahs during peak fruit production (flooded season) resulted in more than 90 per cent of seeds being dispersed to appropriate habitats (table 1 and figure 1).

Many species of Amazonian fruits have morphological structures that enhance buoyancy, which can result in long-distance seed displacement (e.g. [17]). However, for species adapted to fish-mediated dispersal, secondary dispersal by water following defecation is likely to be minimal because seeds generally sink once fruit pulp is removed [9–11,17]. It is likely, therefore, that after defecation by fish, seeds are only locally re-distributed within floodplain habitats, e.g. seeds could aggregate around obstacles like fallen logs as flood waters recede. Furthermore, Colossoma and other frugivorous fishes can disperse viable seeds upstream, downstream and between tributaries within the floodplain to hospitable habitats, replenishing seed banks of plant populations whose seeds are moved unidirectionally downstream by rivers [10].

The dispersal curves of our five Amazonian plant species are multimodal, which has a behavioural explanation: Colossoma disperses most seeds while foraging within a patch of floodplain forest or savannah (figure 1). However, most fish moved to at least one other patch, and a few fish moved to very distant patches, resulting in intermediate and extremely long-distance seed dispersal (figure 1). Frugivorous fishes have been observed to congregate beneath fruiting trees [9,10,15] and could therefore rapidly deplete the local patch of fruit, compelling interpatch movements. Moreover, multimodality may be a common pattern for seeds dispersed by vertebrates. For example, spider monkeys disperse seeds long distances during the day, and shorter distances at night when they are in the same sleep tree for extended periods of time, resulting in a bimodal dispersal pattern [39]. Multimodal dispersal results from more than one process operating on the seed population [48]. For example, Nathan et al. [49] describe a bimodal dispersal pattern for wind-dispersed seeds that results from a combination of relatively local dispersal under canopy-level winds combined with rare, long-distance dispersal due to updrafts. In the present study, there were at least three modes in the dispersal distribution, regardless of plant species: one clearly produced by local movements by all fish, one clearly produced by intermediate-scale movements of some fish, and one clearly produced by large-scale movements of a few fish. The shape of seed dispersal kernels may become more predictable when complex animal behaviour is considered (e.g. [39]).

Impressive as these dispersal distances are, our seed dispersal curves are conservative for several reasons. First, the dense vegetation within floodplain forests decreased the range of the radiotelemetry devices, thus underestimating the time that fish spent in this habitat. Second, three individuals were lost early during our telemetry work and were not rediscovered. Fishing pressure within the reserve was low during the flood season; it is therefore likely that these fish rapidly travelled outside the 5 km range of our 2 day long searches. Third, overexploitation throughout Colossoma's range has reduced average fish size: individuals we followed were substantially smaller (average weight = 1.7 kg) than the 20–30 kg maximum reported size [31,33]. In our study, larger individuals had significantly greater median seed dispersal distances (figure 2). Bigger fish also very likely have longer gut retention times owing to longer digestive tracts. Thus, older and larger individuals should disperse seeds noticeably farther than we present here.

5. Conclusions

Colossoma macropomum fossils have been discovered in Miocene formations [50], suggesting that this species has been dispersing seeds for at least 15 million years. Owing to their extensive mobility and long gut retention times, fruit-eating fishes like Colossoma macropomum probably contribute considerably to seed-mediated long-distance gene flow, the spatial genetic structure, and colonization of distant patches in Amazonian wetland plants. Overexploitation of fruit-eating fish has caused massive declines in population sizes since the 1970s [31,33,34]. Simulation models suggest that dispersal distances depend, in part, on the density of frugivores: when frugivores are more abundant, dispersal kernels exhibit longer tails because food patches are more rapidly exhausted and frugivores must travel farther to find food [51]. Hence, reduced density of Colossoma could decrease the need to travel long distances and, therefore, diminish seed dispersal distances. Furthermore, overfishing has shifted natural Colossoma populations to younger, smaller fish [31,33,34], which are less effective seed dispersers than their older and larger counterparts [11,17,22] (figure 2). Overharvesting of frugivorous fish has myriad effects on seed dispersal effectiveness (sensu [26]) in Amazonian floodplain forests, including a reduction in the quantity of seeds dispersed [22], the viability of consumed seeds [11,17] and the spatial extent of dispersal (figure 2). Thus, overfishing probably compromises long-distance seed dispersal in Amazonian forests.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Geber, P. Marks, P. McIntyre, M. Vellend, K. Flinn and R. Harris for valuable discussions and S. Russo for data. M. Goulding, E. Schupp, A. Manzaneda, M. Horn and S. Russo critiqued previous drafts. We thank associate editor J. Hastings and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism of a previous draft. C. del Busto Rojas, J. Barrera Macedo, J. Vásquez, R. Rosales, S. Vázquez, S. Pérez, L. Ramírez, E. Yumbato, A. Sima, O. Yumbato and V. Saldaña assisted with field and laboratory work. All protocols were approved by Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We are indebted to the Instituto Nacional de Recursos Naturales and the Ministerio de la Producción (Perú) for permits and the Instituto para la Investigación de la Amazonia Peruana for logistical support. Funding was provided by the Wildlife Conservation Society, the National Geographic Society (grant no. 7979-06), and Cornell University's Center for the Environment.

J.T.A. and A.S.F. acquired funding for the study. J.T.A., T.H.P., J.S.S.R. and A.S.F. designed experiments. J.T.A., T.H.P. and J.S.S.R. conducted fieldwork. T.N. designed, implemented, and wrote the methods for the simulation model. T.N. and J.T.A. analysed results. J.T.A. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was edited by T.N., T.H.P. and A.S.F.

References

- 1.Nathan R. 2006. Long-distance dispersal of plants. Science 313, 786–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidler T., Plotkin J. B. 2006. Seed dispersal and spatial pattern in tropical trees. Public Libr. Sci. Biol. 4, e344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohrer G., Nathan R., Volis S. 2005. Effects of long-distance dispersal for metapopulation survival and genetic structure at ecological time and spatial scales. J. Ecol. 93, 1029–1040 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01048.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01048.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins S. I., Cain M. 2002. Spatially realistic plant metapopulation models and the colonization-competition trade-off. J. Ecol. 90, 616–626 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00694.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.00694.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cain M., Milligan B., Strand A. 2000. Long-distance seed dispersal in plant populations. Am. J. Bot. 87, 1217–1227 10.2307/2656714 (doi:10.2307/2656714) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordano P., Garcia C., Godoy J. A., Garcia-Castaño J. L. 2007. Differential contribution of frugivores to complex seed dispersal patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 3278–3282 10.1073/pnas.0606793104 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0606793104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holbrook K. M., Smith T. B. 2000. Seed dispersal and movement patterns in two species of Ceratogymma hornbills in a West African tropical lowland forest. Oecologia 125, 249–257 10.1007/s004420000445 (doi:10.1007/s004420000445) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campos-Arceiz A., Larrinaga A. R., Weerasinghe U. R., Takatsuki S., Pastorini J., Leimgruber P., Fernando P., Santamaria L. 2008. Behavior rather than diet mediates seasonal differences in seed dispersal by Asian elephants. Ecology 89, 2684–2691 10.1890/07-1573.1 (doi:10.1890/07-1573.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulding M. 1980. The fishes and the forest: explorations in Amazonian natural history. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn M. H. 1997. Evidence for dispersal of fig seeds by the fruit-eating characid fish Brycon guatemalensis Regan in a Costa Rican tropical rain forest. Oecologia 109, 259–264 10.1007/s004420050081 (doi:10.1007/s004420050081) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson J. T., Saldaña Rojas J., Flecker A. S. 2009. High-quality seed dispersal by fruit-eating fishes in Amazonian floodplain habitats. Oecologia 161, 279–290 10.1007/s00442-009-1371-4 (doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1371-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araujo-Lima C., Goulding M. 1997. So fruitful a fish: conservation and aquaculture of the Amazon's Tambaqui. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junk W., Soares M., Saint-Paul U. 1997. The fish. In The Central Amazon floodplain: ecology of a pulsing system (ed. Junk W.), pp. 385–408 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe-McConnell R. H. 1987. Ecological studies in tropical fish communities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reys P., Sabino J., Galetti M. 2009. Frugivory by the fish Brycon hilarii (Characidae) in western Brazil. Acta Oecol. Int. J. Ecol. 35, 136–141 10.1016/j.actao.2008.09.007 (doi:10.1016/j.actao.2008.09.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eva H. D., Belward A. S., De Miranda E. E., Di Bella C. M., Gond V., Huber O., Jones S., Sgrenzaroli M., Fritz S. 2004. A land cover map of South America. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 731–744 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2003.00774.x (doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2003.00774.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubitzki K., Ziburski A. 1994. Seed dispersal in flood plain forests of Amazonia. Biotropica 26, 30–43 10.2307/2389108 (doi:10.2307/2389108) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schongart J., Piedade M. T. F., Ludwigshausen S., Horna V., Worbes M. 2002. Phenology and stem-growth periodicity of tree species in Amazonian floodplain forests. J. Trop. Ecol. 18, 581–597 10.1017/S0266467402002389 (doi:10.1017/S0266467402002389) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosales J., Petts G., Salo J. 1999. Riparian flooded forests of the Orinoco and Amazon basins: a comparative review. Biodivers. Conser. 8, 551–586 10.1023/A:1008846531941 (doi:10.1023/A:1008846531941) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Souza-Stevaux M. C., Negrelle R. R. B., Citadini-Zanette V. 1994. Seed dispersal by the fish Pterodoras granulosus in the Parana River Basin, Brazil. J. Trop. Ecol. 10, 621–626 10.1017/S0266467400008294 (doi:10.1017/S0266467400008294) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottsberger G. 1978. Seed dispersal by fish in the inundated regions of Humaita, Amazonia. Biotropica 10, 170–183 10.2307/2387903 (doi:10.2307/2387903) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galetti M., Donatti C. I., Aurelio Pizo M., Giacomini H. 2008. Big fish are the best: seed dispersal of Bactris glaucescens by the Pacu fish (Piaractus mesopotamicus) in the Pantanal, Brazil. Biotropica 40, 386–389 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00378.x (doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00378.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Correa S., Winemiller K., López-Fernández H., Galetti M. 2007. Evolutionary perspectives on seed consumption and dispersal by fishes. Bioscience 57, 748–756 10.1641/B570907 (doi:10.1641/B570907) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenny D. G. 2000. Seed dispersal, seed predation, and seedling recruitment of a neotropical montane tree. Ecol. Monogr. 70, 331–351 10.1890/0012-9615(2000)070[0331:SDSPAS]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9615(2000)070[0331:SDSPAS]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenny D. G., Levey D. J. 1998. Directed seed dispersal by bellbirds in a tropical cloud forest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 6204–6207 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6204 (doi:10.1073/pnas.95.11.6204) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schupp E. W., Jordano P., Gómez J. M. 2010. Seed dispersal effectiveness revisited: a conceptual review. New Phytol. 188, 333–353 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03402.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03402.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordano P., Schupp E. W. 2000. Seed disperser effectiveness: the quality component and patterns of seed rain for Prunus mahaleb. Ecol. Monogr. 70, 591–615 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gómez J. M. 2003. Spatial patterns in long-distance dispersal of Quercus ilex acorns by jays in a heterogeneous landscape. Ecography 26, 573–584 10.1034/j.1600-0587.2003.03586.x (doi:10.1034/j.1600-0587.2003.03586.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers J. C., MacMahon J. A. 1994. A day in the life of a seed: movements and fates of seeds and their implications for natural and managed systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 25, 263–292 10.1146/annurev.es.25.110194.001403 (doi:10.1146/annurev.es.25.110194.001403) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-Aparicio L., Gómez J. M., Zamora R. 2005. Microhabitats shift rank in suitability for seedling establishment depending on habitat type and climate. J. Ecol. 93, 1194–1202 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01047.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01047.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Isaac V. J., Ruffino M. L. 1996. Population dynamics of Tambaqui, Colossoma macropomum Cuvier, in the Lower Amazon, Brazil. Fisheries Manage. Ecol. 3, 315–333 10.1046/j.1365-2400.1996.d01-154.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2400.1996.d01-154.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayley P., Petrere M. 1989. Amazon fisheries: assessment methods, current status and management options. In Proc. of the Int. Large River Symp. (ed. Dodge D. P.), pp. 385–398 Ottowa: Canadian special publication of fisheries and aquatic sciences [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinert T. R., Winter K. A. 2002. Sustainability of harvested pacú (Colossoma macropomum) populations in the northeastern Bolivian Amazon. Conser. Biol. 16, 1344–1351 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01078.x (doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.01078.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santos M. C. F., Ruffino M. L., Farias I. P. 2007. High levels of genetic variability and panmixia of the tambaqui Colossoma macropomum (Cuvier, 1816) in the main channel of the Amazon River. J. Fish Biol. 71, 33–44 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01514.x (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01514.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobler M., Honorio E., Janovec J., Reynel C. 2007. Implications of collection patterns of botanical specimens on their usefulness for conservation planning: an example of two neotropical plant families (Moraceae and Myristicaceae) in Peru. Biodivers. Conserv. 16, 659–677 10.1007/s10531-005-3373-9 (doi:10.1007/s10531-005-3373-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucas M. C., Baras E. 2000. Methods for studying spatial behaviour of freshwater fishes in the natural environment. Fish Fisheries 1, 283–316 10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00028.x (doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00028.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lucas M., Baras E. 2001. Migration of freshwater fishes. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freund J. G., Hartman K. J. 2002. Influence of depth on detection distance of low-frequency radio transmitters in the Ohio River. North Am. J. Fisheries Manage. 22, 1301–1305 (doi:10.1577/1548-8675(2002)022<1301:IODODD>2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russo S. E., Portnoy S., Augspurger C. 2006. Incorporating animal behavior into seed dispersal models: implications for seed shadows. Ecology 87, 3160–3174 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[3160:IABISD]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[3160:IABISD]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vellend M., Myers J., Gardescu S., Marks P. L. 2003. Dispersal of Trillium seeds by deer: implications for long-distance migration of forest herbs. Ecology 84, 1067–1072 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1067:DOTSBD]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1067:DOTSBD]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wehncke E. V., Hubbell S., Foster R. B., Dalling J. W. 2003. Seed dispersal patterns produced by white-faced monkeys: implications for the dispersal limitation of neotropical tree species. J. Ecol. 91, 677–685 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00798.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00798.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westcott D. A., Bentrupperbäumer J., Bradford M. G., McKeown A. 2005. Incorporating patterns of disperser behaviour into models of seed dispersal and its effects on estimated dispersal curves. Oecologia 146, 57–67 10.1007/s00442-005-0178-1 (doi:10.1007/s00442-005-0178-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jerozolimski A., Ribeiro M. B. N., Martins M. 2009. Are tortoises important seed dispersers in Amazonian forests? Oecologia 161, 517–528 10.1007/s00442-009-1396-8 (doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1396-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray K. G. 1988. Avian seed dispersal of three neotropical gap-dependent plants. Ecol. Monogr. 58, 271–298 10.2307/1942541 (doi:10.2307/1942541) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiegel O., Nathan R. 2007. Incorporating dispersal distance into the disperser effectiveness framework: frugivorous birds provide complementary dispersal to plants in a patchy environment. Ecol. Lett. 10, 718–728 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01062.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01062.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilati R., Adrian I. D., Carneiro J. W. P. 1999. Performance of seed germination of Cecropia pachystachya Trec. (Cecropiaceae) from the digestive tract of Ptedoras granulosus (Valenciennes, 1833) of the floodplain of the Upper Parana River. Interciencia 24, 381–388 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saint-Paul U., Zuanon J., Correa M. A. V., Garcia M., Fabre N. N., Berger U., Junk W. J. 2000. Fish communities in central Amazonian white- and blackwater floodplains. Environ. Biol. Fishes 57, 235–250 10.1023/A:1007699130333 (doi:10.1023/A:1007699130333) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higgins S. I., Nathan R., Cain M. 2003. Are long-distance dispersal events in plants usually caused by non-standard means of dispersal? Ecology 84, 1945–1956 10.1890/01-0616 (doi:10.1890/01-0616) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nathan R., Katul G. G., Horn H. S., Thomas S. M., Oren R., Avissar R., Pacala S., Levin S. A. 2002. Mechanisms of long-distance dispersal of seeds by wind. Nature 418, 409–413 10.1038/nature00844 (doi:10.1038/nature00844) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundberg J. G., Machado-Allison A., Kay R. F. 1986. Miocene characid fishes from Colombia: evolutionary stasis and extirpation. Science 234, 208–209 10.1126/science.234.4773.208 (doi:10.1126/science.234.4773.208) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morales J. M., Carlo T. A. 2006. The effects of plant distribution and frugivore density on the scale and shape of dispersal kernels. Ecology 87, 1489–1496 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1489:TEOPDA]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1489:TEOPDA]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]