Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT) on survival time and outcome when applied after resection of low-grade glioma (LGG) of World Health Organization grade II. From January 1982 through December 2006 we treated 1024 patients who had glioma with stereotactic implantation of iodine-125 seeds and SBT in accordance with a prospective protocol. For the present analysis, we selected 95 of 277 patients with LGG, in whom SBT was applied to treat progressive (43 patients) or recurrent (52 patients) tumor after resection. At 24 months after seed implantation, the tumor response rate was 35.9%, and the tumor control rate was 97.3%. The median progression-free-survival (PFS) duration after SBT was 52.7 ± 7.1 months. Five-year and 10-year PFS probabilities were 43.4% and 10.7%, respectively. Malignant tumor transformation, the diagnosis “astrocytoma,” and tumor volume >20 mL were significantly associated with reduced PFS. Tumor progression or relapse after SBT (53 of 95 patients) was treated with tumor resection, a second SBT, chemotherapy, and/or radiotherapy. The median overall survival duration (from the first diagnosis of LGG until the patient's last contact) was 245.0 ± 4.9 months. Patients still under observation after seed implantation had a median follow-up time of 156.4 ± 55.7 months. Perioperative transient morbidity was 1.1%, and the frequency of permanent morbidity caused by SBT was 3.3%. In conclusion, SBT of recurrent or progressive LGG after resection located in functionally critical brain areas has high local efficacy and comparably low morbidity. Referred to individually adopted glioma treatment concepts SBT provides a reasonably long PFS, thus improving overall survival. In selected patients, SBT can lead to delays in the application of chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy.

Keywords: 125-Iodine seeds, brachytherapy, low grade glioma, resection, stereotaxy

The management of low-grade glioma (LGG; ie, diffuse astrocytoma [LAA], oligodendroglioma [LOG], and mixed oligoastrocytoma [LOA] of World Health Organization [WHO] grade II) has been controversial. Therapeutic options include stereotactic biopsy and subsequent radiological monitoring, resection, radiation therapy (RT), and chemotherapy.1,2 In most cases, infiltrative growth of these tumors and/or their location in functionally critical brain areas hinder curative surgery. The median duration of survival for patients with LGG is 7–8 years.3 Among other factors, one factor complicating the therapeutic management of these patients is malignant tumor progression, which occurs in the majority of patients within 3–6 years after diagnosis.4

Stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT) with 125iodine (125I) seeds enables long, protracted, focused irradiation at low doses. It has been shown in a small number of institutional case series to be a valuable tool for first-line treatment of small and circumscribed LGGs that are well delineated (according to computed tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] criteria) but not accessible for tumor resection due to their location.5,6 WHO grade II glioma is preferentially diagnosed in younger patients and can be perceived as a chronic disease.7 Thus, postponing chemotherapy or RT, for which repeated application is hindered by severe side effects, by combining SBT with tumor resection may be a promising therapeutic concept.8,9

In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed data for 95 patients who were treated with SBT according to a prospective treatment protocol for recurrent or progressive tumor after surgical resection of LGG. The primary objective of this analysis was to assess the impact of SBT on progression-free-survival (PFS) and survival after SBT, as well as overall survival (ie, time from first diagnosis of a glioma to the last follow-up visit). In addition, we recorded the clinical outcome and analyzed covariates with regard to their impact on PFS after SBT.

Patients and Methods

Patients

From January 1989 through December 2006, a total of 977 patients were treated at the Department of Stereotaxy and Functional Neurosurgery, University Hospital, Cologne, Germany, with 125I-seeds and SBT for a cerebral glioma. Another 47 patients were treated with the same methodology by one of us (V.S.) during the years 1982–1989 at the German Cancer Research Centre in Heidelberg. All patients, who had given informed consent in writing, were selected for SBT on the basis of the same inclusion criteria: Karnofsky performance score (KPS) ≥60, well-defined tumor borders on CTs or MRIs, tumor diameters ≤50 mm (prior to year 1995) or ≤40 mm (since year 1995), tumor location in functionally critical brain areas, and tumor progression. In most cases, SBT was applied as first-line treatment. For the present analysis, we considered data only for patients who underwent SBT for recurrent or progressive residual WHO II glioma after neurosurgical tumor resection (98 of 271 patients with LGG). Three of 98 patients were excluded because of incomplete follow-up documentation.

Patient Evaluation

The follow-up protocol prescribed regular neurological and radiological examinations in 3-month intervals during the first year after seed implantation and in 6-month intervals thereafter. For the present update, missing data were obtained from patient records or by telephone interviews. In patients with neurologic sequelae caused by SBT, we rated the degree of permanent or transient impairment on the basis of a modified Rankin scale.10–12 Radiological follow-up was mainly CT based in 43 patients and completely MRI based in 52 patients. Maximum tumor diameters were measured on at least 2 different reconstruction planes of follow-up CTs or /MRIs. The maximum diameter (d) was used to calculate tumor volumes (V) according to the formula V = π/6d3. To classify the response to therapy, we considered the smallest tumor volume documented within 24 months after seed implantation. We used diameters instead of true volumetric analysis because this method was applied for radiological analysis prior to the year 1996. McDonald criteria were modified in such a way that not only contrast enhancement but also other signal changes on CTs (reduced intensity) or T2-weighed MRIs (increased intensity) suspicious for tumor were considered when tumor response was evaluated.13

In addition, we co-registered follow-up CTs or MRIs with treatment planning data to colocalize image changes with tumor extension prior to SBT and dose distribution. The biological significance of radiological findings indicative of active tumor (ie, new contrast enhancement and/or edema beyond the therapeutic isodose) was determined by resection or biopsy or noninvasively by PET imaging.14 We classified new contrast enhancement inside a tissue volume enclosed by the therapeutic isodose as blood-brain-barrier (BBB) breakdown caused by SBT if these tumors did not progress within 6 months after this finding.

Stereotactic Brachytherapy Methods

In general anesthesia, a modified Riechert-Mundinger stereotactic frame was fixed on the patient's head, and an intraoperative stereotactic CT examination was performed. Prior to January 1996, tumor borders were defined on CTs only. After that date, CT data were combined with images from preoperative MRIs. For image processing and CT-based/MRI-based 3D treatment planning, we used dedicated software (STP; Stryker-Howmedica).5

Activities (median activity per patient, 12 ± 6.7 mCi) and numbers of the seeds (median number per patient, 4 ± 3; GE Healthcare Buchler), as well as entrance and target points for seed implantation, were chosen according to the 3D tumor outline, which had to be encompassed by the therapeutic radiation dose. For SBT, 125I-seeds were loaded into double-layered Teflon catheters (Best Medical International). After stereotactically guided implantation, each seed-catheter was fixed with a titanium clip and methylacrylate (Palacos; Biomet) in the 8-mm trephination borehole. Stereotactic x-rays taken in the operating room documented the seed position.15 A cumulative therapeutic tumor surface dose ranging from 50 to 65 Gy was delivered within 9 months (initial dose rate, 0.7 Gy/day).

Statistical Methods

The date of the last follow-up was 31 March 2010. The reference point of the current study was the date of seed implantation. End points for survival analysis were date of tumor progression after SBT and patient death, irrespective of its cause.9,16 Data were analyzed with SPSS for Windows statistical software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc). The independence of variables was examined using the χ2 test procedure (significance level, P < .05). With use of the Kaplan-Maier method, we calculated overall survival (ie, time from first diagnosis until death or last follow-up), survival after seed implantation (ie, time from surgery until death or last follow-up), and PFS after seed implantation (ie, time from surgery until treatment and/or diagnosis of tumor relapse or progression).17 In addition, we performed univariate analysis (by log-rank test; significance level, P< .05) and multivariate analysis (by Cox proportional hazards model, likelihood-ratio statistic, and forward selection) to determine possible covariates with impact on PFS.18,19 Data other than survival times are listed as median values together with standard deviations. Survival times are given as median values together with standard error and 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 list the characteristics of 95 patients with WHO grade II glioma analyzed in the present study. The variables age, tumor volume, and KPS at seed implantation were not significantly different among patients with LAA (69 patients), LOA (14 patients), or LOG (12 patients) (Table 3). In 52 of 95 cases, we treated a recurrent tumor after macroscopically complete tumor resection (median time from first surgery to 125I-seed implantation, 17 months; range, 3–171 months); radicality of resection was classified by neurosurgeons and/or radiologists admitting the patient for SBT. In these patients, we performed stereotactic biopsy together with seed implantation, which confirmed the first histological diagnosis in all cases. Forty-three of 95 patients underwent SBT for progressive residual tumor after incomplete tumor removal (median time from surgery to 125I-seed implantation, 4 months; range, 1–8 months). Three patients with LGA had already been treated with external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) (radiation dose, 56 Gy).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 52 patients treated with stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT) for recurrence of low-grade glioma after tumor resection

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 |

| Female | 17 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median ± SD | 35.4 ± 11.2 |

| Range | 8.4–61.7 |

| Karnofsky performance score (%) | |

| Median ± SD | 90 ± 10.2 |

| Range | 60–100 |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |

| Median ± SD | 17.8 ± 16.8 |

| Range | 0.6–65.0 |

| Histological tumor classification | |

| Astrocytoma | 38 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 7 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 7 |

| Tumor location | |

| Frontal | 29 |

| Parietal | 4 |

| Occipital | 2 |

| Temporal | 13 |

| Basal ganglia/diencephalon | 1 |

| Ventricle-septal area | – |

| Brainstem | 1 |

| Posterior fossa | 2 |

Note: Data are no. of patients unless otherwise indicated. SD indicates standard deviation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 43 patients treated with stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT) for low-grade glioma progressive tumor after partial tumor resection

| Sex | |

| Male | 28 |

| Female | 15 |

| Age (years) | |

| Median ± SD | 37.1 ± 12.8 |

| Range | 13.5–68.4 |

| Karnofsky performance score (%) | |

| Median ± SD | 90 ± 9.1 |

| Range | 60–100 |

| Tumor volume (mL) | |

| Median ± SD | 26.0 ± 15.4 |

| Range | 2.5–57.0 |

| Histological tumor classification | |

| Astrocytoma | 31 |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 7 |

| Oligodendroglioma | 5 |

| Tumor location | |

| Frontal | 15 |

| Parietal | 4 |

| Occipital | 2 |

| Temporal | 19 |

| Basal ganglia/diencephalon | 1 |

| Ventricle-septal area | 1 |

| Brainstem | 1 |

| Posterior fossa | – |

Note: Data are no. of patients unless otherwise indicated. SD indicates standard deviation.

Table 3.

Distribution of values for age, tumor volume, and Karnofsky performance score at the time of 125iodine seed implantation among patients with diffuse astrocytoma (69 patients), mixed oligoastrocytoma (14 patients), or oligodendroglioma (12 patients) and numbers of patients with malignant tumor transformation

| Characteristic | Astrocytoma | Oligoastrocytoma | Oligodendroglioma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 35.7 ± 10.5 | 37.1 ± 15.6 | 42.9 ± 14.2 |

| Tumor volume, mL | 23.1 ± 14.3 | 21.1 ± 16.2 | 30.0 ± 14.7 |

| Karnofsky performance score | 90 ± 9.3 | 95 ± 11.2 | 95 ± 10.9 |

| Malignant tumor transformation, (no. of patients | 22 | 4 | 1 |

Note: Data are median±standard deviation, unless otherwise indicated.

Tumors were located in functionally critical hemispheric brain territories in 92.6% of patients, in midline structures of the brain in 5.3% of patients (diencephalon/basal ganglia, 2.1%; brainstem, 2.1%; and ventricle/septal area, 1.1%), and in the posterior fossa in 2.1% of patients. Seventeen (17.9%) of 95 patients underwent SBT for a tumor extending into a second brain area adjacent to the main tumor location.

Perioperative Mortality and Morbidity

There were no surgery-related fatal events (perioperative mortality rate, 0%). The rate of perioperative transient morbidity was 1.1% (1 patient had cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula and spontaneous occlusion after temporary lumbar CSF drainage).

Survival and Salvage Therapy after SBT

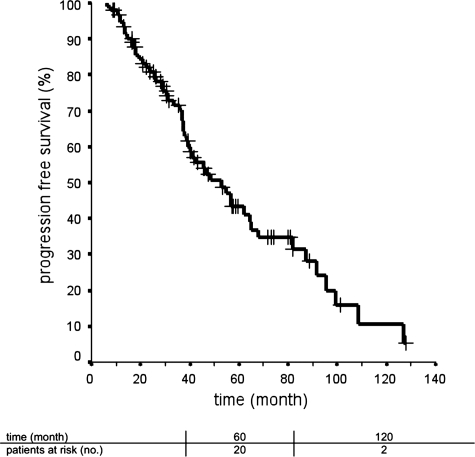

The median cumulative PFS after SBT was 52.7 ± 7.1 months (95% CI, 38.8–66.6 months) (Fig. 1). Fifty-three (55.8%) of 95 patients presented with tumor recurrence or progression after SBT. Twenty-three of these 53 patients were initially assigned SBT for progressive tumor, and 30 of 53 patients received SBT for a tumor relapse after glioma surgery. The median PFS for patients with progressive tumor (56.5 ± 7.3 months; 95% CI, 42.2–70.8 months) tended to be longer than the PFS for patients treated with SBT for tumor recurrence (42.0 ± 5.8 months; 95% CI, 30.6–53.4 months). This difference, however, was statistically not significant (P= .18).

Fig. 1.

Progression free survival after implantation of 125iodine seeds. Ninety-five patients were treated with stereotactic brachytherapy for low-grade glioma after tumor resection.

The 5-year PFS probability was 43.4%, and the 10-year PFS probability was 10.7%. For patients with progressive tumor, 5-year and 10-year PFS estimates were 48.0% and 0%, respectively; for patients with a tumor relapse, the values were 38.7% and 9.7%, respectively. When stratified for tumor type, the median PFS was 42.0 ± 5.8 months for LAA, 68.0 ± 15.7 months for LOG, and 62.1 ± 18.8 months for LOA. The median follow-up time for 42 patients without tumor relapse or progression after SBT was 138.7 ± 60.0 months (range, 51.7–275.1 months).

Forty-four of 53 patients with tumor relapse after SBT were treated with either tumor resection, RT, a second round of SBT, chemotherapy, or combinations of these treatment modalities. In 3 of 12 patients, salvage therapy was not performed because of bihemispheric tumor extension (2 patients) or spinal tumor dissemination (1 patient). Two of these 12 patients decided against salvage therapy (one patient had hemiplegia after first tumor resection, and the other patient made this decision for personal reasons). In 4 patients, clinical follow-up after the diagnosis of tumor relapse was incomplete. Table 4 lists different salvage therapies with respect to tumor location, and Table 5 presents the number of patients treated with different salvage therapy regimens.

Table 4.

Salvage therapy for tumor relapse or progression after stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT) subject to tumor localization

| Tumor localization | Salvage therapy for tumor relapse or progression after SBT, no. of patients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resection | Radiation therapy | Chemotherapy | Second SBT | |

| Frontal | 24 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Parietal | 4 | 3 | – | 2 |

| Temporal | 10 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Occipital | 2 | 1 | – | – |

| Midline | – | – | 1 | – |

| Posterior fossa | – | – | – | 1 |

| Total | 40 | 19 | 13 | 19 |

Table 5.

Salvage therapy regimens for tumor relapse or progression after stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT)

| Salvage therapy for tumor relapse or progression after SBT | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Resection | 15 |

| Radiation therapy | 2 |

| SBT | 3 |

| Resection + radiation | 4 |

| Resection + SBT | 3 |

| Resection + chemotherapy | 3 |

| Resection + radiation + SBT | 5 |

| Resection + radiation + chemotherapy | 1 |

| Resection + SBT + radiatio-/chemotherapy | 2 |

| Resection + SBT + radiation + salvage chemotherapy | 3 |

| Radiation + SBT | 1 |

| Radiation + salvage chemotherapy | 1 |

| SBT + chemotherapy | 1 |

| Total | 44 |

Malignant tumor transformation was verified by resection or biopsy in 27 (50.9%) of 53 patients who had glioma relapse or progression after SBT (WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytoma, 22 patients; WHO grade III anaplastic oligoastrocytoma, 4 patients; and WHO grade III anaplastic oligodendroglioma, 1 patient). The proportion of patients with malignant transformation was almost equally distributed between those who received SBT for recurrent tumor (16 of 27 patients) and those treated for a tumor progression (11 of 27 patients).

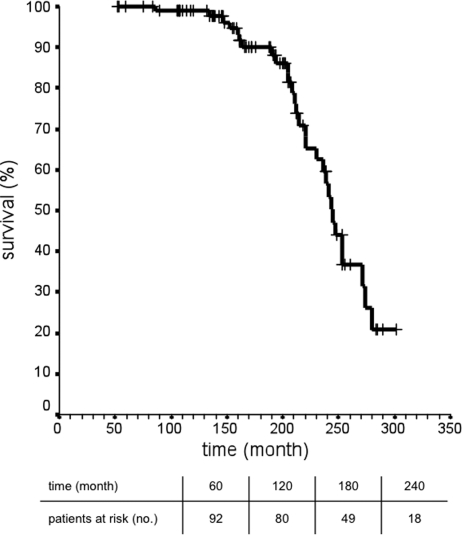

The median survival time after seed implantation was 237.6 ± 12.6 months (95% CI, 216.8–258.3). Patients still under observation had a median follow-up time after seed implantation of 156.4 ± 55.7 months (range, 52.4–275.1 months). The median cumulative overall survival time was 245.0 ± 4.9 months (95% CI, 235.3–254.7 months) (Fig. 2). Median overall survival was 246.6 ± 21.6 months (95% CI, 204.2–289.0 months) for patients treated with SBT for a tumor rest and 244.0 ± 5.0 months (95% CI, 234.1–253.8 months) for patients treated with SBT for recurrent tumor. This difference was statistically not significant (P= .615).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (ie, time from first diagnosis until last patients’ contact) after implantation of 125iodine seeds and stereotactic brachytherapy for low-grade glioma after tumor resection (in 95 patients).

All deaths occurred 86–274 months after seed implantation. Twenty (21.1%) of 95 patients died of brain tumor, 3 of whom died of a new brain tumor remote from primary tumor location, and 2 (2.1%) of 95 patients died of causes unrelated to brain tumor. In 7 (7.4%) of 95 patients, we could not determine the cause of death. Fifteen of 29 events occurred in the group treated with SBT for progressive tumor, and 14 of 29 events occurred in the group treated for a tumor relapse.

Prognostic Factors

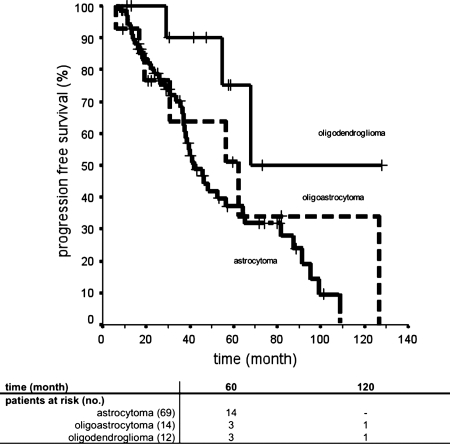

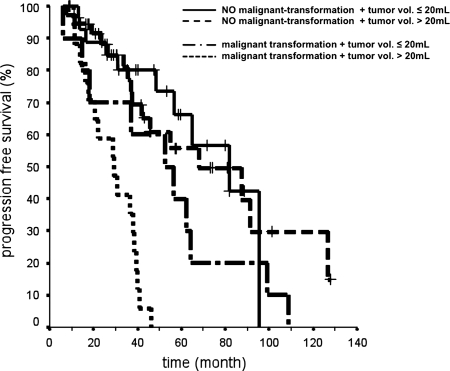

Univariate analysis of covariates showed that neither sex, age, KPS, treatment volume, treatment date (treatment planning was CT based prior to January 1996 or MRI based since January 1996), tumor status, nor tumor extension did prove to be of significance for PFS (Table 6). The PFS of patients with LAA was significantly shorter (37.2% at 5 years) versus that for patients with LOG (75.0% at 5 years; P= .027) (Fig. 3). Differences in survival times did not reach statistical significance when patients with LOA (5-year PFS, 51.1%) were compared with patients with LAA (P= .42) or LOG (P= .1448). The variable malignant tumor progression was statistically significant associated with reduced PFS (P < .001). Median PFS after SBT was 36.8 ± 7.0 months (95% CI, 23.1–50.5 months) in patients with malignant tumor transformation and 81.6 ± 12.6 months (95% CI, 56.9–10.4 months) in patients without a malignant tumor phenotype (Fig. 4).

Table 6.

Covariates considered for univariate and multivariate analysis of their impact on progression-free survival (PFS)

| Covariate | No. of patients | 5-year PFS, % | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | .339 | ||

| Female | 32 | 53.5 | |

| Male | 63 | 38.1 | |

| Histology | .027 | ||

| (a) Astrocytoma | 69 | 37.2 | .027 for (a) vs (c) |

| (b) Oligoastrocytoma | 14 | 51.1 | .42 for (a) vs (b) |

| (c) Oligodendroglioma | 12 | 75.0 | .1448 for (b) vs (c) |

| Age, years | .167 | ||

| ≤45 | 75 | 40.2 | |

| >45 | 20 | 55.1 | |

| Karnofsky performance score | .673 | ||

| <90 | 21 | 46.5 | |

| ≥90 | 74 | 42.4 | |

| Treatment volume, mL | .242 | ||

| ≤20 | 41 | 57.1 | |

| >20 | 54 | 34.0 | |

| Treatment date | .398 | ||

| Before January 1996 | 40 | 38.3 | |

| After January 1996 | 55 | 48.6 | |

| Tumor extension | .791 | ||

| One region | 78 | 42.6 | |

| Two regions | 17 | 53.1 | |

| Tumor status | .177 | ||

| Rest | 43 | 48.0 | |

| Relapse | 52 | 38.7 | |

| Malignant tumor transformation | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 27 | 14.8 | |

| No | 68 | 66.0 |

Note: Data are P values after univariate analysis and 5-year PFS-rates for subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Progression-free survival after implantation of 125iodine seeds and stereotactic brachytherapy for World Health Organization (WHO) grade II astrocytoma (69 patients), WHO grade II oligoastrocytoma (14 patients), and WHO grade II oligodendroglioma (12 patients). The diagnosis of astrocytoma had a significant negative impact on survival, compared with the diagnosis of oligodendroglioma (P= .027, by log-rank test).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves depicting the influence of malignant tumor transformation and tumor size on progression-free survival (PFS) after implantation of 125iodine seeds and stereotactic brachytherapy in patients with low-grade glioma. Median PFS times (±standard deviation) for different groups are as follows: (1) no malignant transformation plus tumor volume ≤20 mL, 81.6 ± 18.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 45.6–117.7); (2) no malignant transformation plus tumor volume >20 mL, 68.0 ± 21.4 months (95% CI, 26.1–110.0); (3) malignant transformation plus tumor volume ≤20 mL, 52.7 ± 15.2 months (95% CI, 22.8–82.6); and (4) malignant transformation plus tumor volume >20 mL, 29.1 ± 5.7 months (95% CI, 19.9–40.4)

After multivariate analysis using the same covariates as for univariate analysis factors associated with reduced PFS were malignant tumor transformation and tumor volume >20cc (Table 7 and Fig. 4).

Table 7.

Probability values for variables being significantly associated with reduced progression-free survival after stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT)in a Cox proportional hazards model18

| Covariate | P | Relative risk | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malignant tumor transformation | .0001 | 3.8 | (2.1–6.7) |

| Tumor volume >20 mL | .044 | 0.5 | (0.3–0.9) |

Clinical and Radiological Course

Radiological follow-up after SBT was complete for 92 of 95 patients. Within the first 24 months after seed implantation, 11 (12.0%) of 92 patients responded with complete tumor remission, and 22 patients (23.9%) responded with partial remission (tumor response rate, 35.9%). SBT had stabilized the tumor growth in 57 cases (62.0%). The local tumor control rate was 97.9%. Two patients (2.1%) presented with tumor progression ≤6 months after seed implantation. In 15 patients (16.3%), we registered an early tumor relapse 11–24 months after seed implantation.

CTs or MRIs displayed new contrast enhancement inside the irradiated target volume in 67 (72.8%) of 92 patients. Eight of these tumors progressed within 6 months after documentation of new tissue staining. In the remaining 59 patients (64.1%), contrast enhancement was supposed to be caused by SBT. When follow-up images were coregistered with treatment planning images, radiogenic BBB breakdown projected onto isodose lines (radiation dose after SBT) ranging from 150 to 200 Gy. The median time from seed implantation to first documentation of radiogenic BBB breakdown was 9.1 ± 11.4 months.

In 90 patients, radiological findings could be correlated with the clinical course. Progressive radiogenic BBB (ie, contrast enhancement plus perilesional edema with mass effect) occured in 8 of 90 patients in association with deterioration of their neurological status. The deterioration was transient in 5 of 90 patients (transient morbidity rate, 5.6%) and permanent in 3 of 90 patients (permanent morbidity rate, 3.3%) (Table 8). In 3 of 8 patients with symptomatic radiogenic BBB breakdown, tumor volumes treated with SBT were ≤20 mL and in 5 of 8 patients >20 mL.

Table 8.

Patients with deterioration of the clinical status after stereotactic brachytherapy (SBT)

| ID | Tumor localization | Status before SBT | Status after SBT | Duration of impairment | Modified Rankin scale (new impairment and/or worsening of symptoms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR | Temporal plus basal ganglia | No neurological deficit | Hemiparesis | Permanent | 4 |

| RJ | Parietal | No neurological deficit, seizures | Hemiparesis, preference of legs, some improvement within one year | Permanent | 2 |

| MD | Temporal (dominant hemisphere) | Seizures | Increased seizure frequency | 8 months | 1 |

| PS | Temporal | Seizures | Increased seizure frequency | 5 months | 1 |

| DK | Frontal (dominant hemisphere) | Brachiofacial motor weakness, incomplete aphasia | Worsening of preexisting symptoms | ∼2 years (difficult to distinguish from tumor progression) | 2 |

| RU | Temporal | Seizures | Increased seizure frequency | 6 months | 1 |

| LP | Frontal (tumor infiltration of precentral gyrus) | No neurological deficit, seizures | Spastic leg paresis (foot elevation, some improvement after 6 months) | Permanent | 2 |

| GM | Parietal | No neurological deficit, seizures | Ataxia left leg, complete improvement after dexamethason | Several weeks | 1 |

Note: The degree of permanent or transient impairment is rated according to a modified Rankin scale. Modified Rankin scale is as follows: 0 = no symptoms at all; 1 = no significant disability despite symptoms, able to carry out all usual duties and activities; 2 = slight disability, unable to carry out all previous activities, but able to look after own affairs without assistance; 3 = moderate disability, requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance; 4 = moderately severe disability, unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance; 5 = severe disability, bedridden, incontinent, and requiring constant nursing care and attention; 6 = dead. ID, patient identification.

Twenty (21.0%) of 92 patients developed cysts in immediate vicinity to the tissue volume treated with SBT. In 7 patients with cysts, we registered rapid progression of solid tumor parts. Another 10 patients (10.9%) with stable cyst volume received no specific therapy for the cysts. Three of 92 patients with progressive, space-occupying cysts were treated with stereotactic cyst aspiration. Evacuated cysts did not relapse.

Discussion

Survival after SBT

We retrospectively analyzed 95 patients who received SBT to treat recurrent or progressive residual LGG after tumor resection located in functionally critical hemispheric or subcortical brain areas. Schnell et al.20 first investigated, in a prospective pilot study, the efficacy of combined microsurgery and SBT as first-line treatment for LGG with diameters exceeding 4 cm and complex tumor location. The primary aim of tumor resection performed in 18 of 31 patients (the de novo group) was reduction of larger tumor volumes to a size suitable for SBT. Patients in the de novo group were compared with 13 patients who underwent immediate SBT for small (diameter, <4 cm) recurrent LGG (control group). The 5-year PFS after SBT was 72% in the de novo group and 62% in the control group.20

Given that patients in the de novo group were roughly comparable to those patients treated in the here-presented series with SBT for progressive tumor, and given that patients in the control group were comparable to those with recurrent tumors, then the actual PFS rates at 5 years are substantially lower (48.0% and 38.7%, respectively). One plausible explanation for this discrepancy may be the different treatment volumes in the 2 series. Although, in the study by Schnell et al.,20 the median tumor volume treated with SBT was ∼9 mL, patients of the here-analyzed cohort had median tumor volumes of 26.0 mL (tumor relapse) or 17.8 mL (progressive tumor). Kreth et al.7 reported that the variable tumor volume was a significant predictor for survival after de novo SBT of a LGG in the long-term run. Patients with tumor volumes exceeding 20 mL had a 5-year PFS probability of 41%, which is roughly comparable to the results presented here. However, if only patients in the present study who have smaller tumors (volume of ≤20 mL) are considered, then the 5-year survival rates of 68% are very close to the survival data published by Schnell et al.20

Another comparison group for patients of the present analysis is patients treated with EBRT for supratentorial LGG after surgery. In a phase III study performed by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG), the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG), and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), the median PFS was 5–5.5 years and the 5-year PFS was 47%–55%, which is roughly comparable to the data presented here (4.4 years and 48% after SBT, respectively).9 The median survival time after SBT, however, was 19.8 years, which is much longer than after EBRT (6–9.8 years).9 Moreover, the corresponding Kaplan-Meier curve (Fig. 2) exhibits a pattern that, due to a hyperbolic course in its first part, is atypical for long-term analysis of LGG.3,7 Furthermore, survival data reported in the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) study for LGG after tumor resection and percutaneous RT are much shorter than in the present analysis. Even after stratification for prognostic factors, the median survival duration for patients belonging to groups with a very low risk (score, 0 or 1) was comparably lower (∼108 months).21 One possible explanation for these differences may be that our data reflect the effect of various salvage therapies (ie, SBT, resection, EBRT, and chemotherapy) individually adopted to the patients over many years rather than the effect of a prospectively applied, fixed treatment schedule. In the present study, deaths did not occur until 86–273 months after 125I-seed implantation, which may in part explain both the unusual long survival time and the atypical Kaplan-Meier survival curve. However, if this observation is an effect of individually adopted glioma therapy integrating STB as treatment modality, or of a not yet determined selection factor biasing the outcome, needs further clarification in the future.

Factor Analysis

According to one of the most comprehensive analyses in this field, which used data for 621 patients with LGG from 2 EORTC studies, age >40 years, astrocytoma, tumor diameter >6 cm, tumor crossing the midline, and presence of neurologic deficits before surgery were unfavorable prognostic factors for survival.21 In the NCCTG/ECOG/RTOG phase III trials of EBRT, significantly better survival was associated with oligodendroglioma or oligo-dominant mixed tumor histology, small tumors (<5 cm), and/or young age (age, <40 years).9 In a “BEST” model of survival and PFS after de novo SBT in LGG (A “BEST” model contains only variables that were significantly associated with the chosen endpoints after adjustment for effects of other variables in the model), Kreth et al.7 identified the variables age >50 years, KPS <90, tumor volume >20 mL, and contrast staining on CTs as negative predictors.

In the present study, univariate analysis of covariates revealed that 2 variables had significant influence on survival. First, patients with astrocytomas had significantly shorter PFS rates (estimated 5-year PFS rate, 37.2%) than did patients with oligodendrogliomas (estimated 5-year PFS rate, 75.0%). This result resembles the findings from the EORTC study analysis and the NCCTG/ECOG/RTOG phase III trials of EBRT.9,21 Second, patients presenting with malignant tumor transformation after SBT had a shorter PFS after SBT (median PFS duration, 36.8 ± 7.0 months), compared with patients who did not have a malignant tumor phenotype (median PFS duration, 81.6 ± 12.6 months) at this time point. This result recalls findings from the long-term analysis of patients with LGG performed by Kreth and colleagues, who demonstrated a disadvantageous effect of malignant transformation on survival after SBT. With regard to the time period between tumor progression after SBT and death or last follow-up (called “post recurrence survival”), the reported median survival rate was 12% with malignant transformation and 31% without malignant transformation (P< .001).7

Adverse Effects of Seed Implantation and of SBT

Most tumors treated with SBT were located in functionally critical brain regions. Thus cero morbidity and only minor transient mortality represent a comparably low complication rate. Because we did not routinely perform postoperative CTs or MRIs, we cannot exclude the possibility that silent hemorrhages occurred. Image-guided and computer-assisted 3D treatment planning enabling the surgeon to avoid structures at risk, such as blood vessels and/or larger fiber bundles (eg, internal capsule and pyramidal tract) may have contributed to this good outcome. In addition, Schnell et al.,20 who used MRI-based treatment planning for seed implantation in 31 patients, reported only minor complications for 2 cases (seed dislocation and minor headache). When stereotactic biopsy and seed implantation were performed on the basis of CT in 499 patients, perioperative mortality and morbidity rates were 0.9% and 1.8%, respectively. In 4 cases from that study, adverse events were clearly related to the biopsy.6

The aim of SBT is the circumscribed destruction of tumor tissue through application of a necrotizing radiation dose. Exposure of a particular tumor volume to doses >200 Gy causes specific tissue changes, such as necrosis and BBB breakdown inside the treated tumor, which in turn can lead to characteristic image changes on follow-up CTs and/or MRIs.22,23 In the present study, the frequency of radiogenic image changes was 64.1% for a margin prescription dose of 50–65 Gy. Image changes developed in 5.6% of the patients concurrently with transient and in 3.3% concurrently with permanent deterioration of their clinical status. In all symptomatic patients, radiogenic BBB breakdown was associated with perilesional white matter edema exerting mass effect on surrounding brain tissue. Kreth and colleagues determined the risk of SBT using data from 515 patients with LGG. Depending on the margin prescription dose (60 Gy for temporary implants vs 100 Gy for permanent implants), the rates of transient radiogenic complications were 5.6% and 5.3%, respectively; for progressive clinical deterioration, the rates were 0.8% and 3.6%, respectively. Clinical symptoms occurred coincidently with progressive radiogenic image changes. According to univariate analysis, larger values for treatment volume, volume of tissue encompassed by 200 Gy, volume of the 60 Gy isodose outside the target volume, reference dose, and the number of implanted sources were statistically significant associated with higher toxicity.6 Interestingly, data on toxicity after SBT are also consistent with those derived from EBRT studies. The NCCTG/ECOG/RTOG phase III trials of EBRT report a 2-year actuarial incidence of grade 3–5 radiation necrosis of 2.5% for 50.4 Gy and of 5.0% for 64.8 Gy.9

Limitations of the study and summary

To our knowledge, the present study includes the largest reported group of patients (n= 95) treated with SBT after resection of LGG to date. A weak point of this study is the retrospective data analysis, which is balanced only to a certain degree by the prospectively applied patient selection and treatment protocol. In addition, the comparably high KPSs in the patients and the fact that gliomas treated with SBT had well-defined tumor borders on CTs/MRIs may have positively biased the presented results. Moreover, the 24-year treatment interval can be considered a bias, because early CT-based treatment planning versus more recent MRI-based treatment planning and assessment of treatment effects and technical improvement of EBRT and/or microsurgery over time can create “different” patients in the same cohort. On the other hand, a long observation interval is necessary for a realistic display of the long-term courses for these patients.

Despite these objections, we emphasize the following points. Both tumor resection and SBT are able to destroy viable tumor tissue effectively. The maximum degree of resection, however, is determined by the infiltrative growth pattern of LGG and/or by tumor location. When, in large case studies, the radicality of surgery was quantified by volumetric analysis, gross total tumor resection of an LGG was possible in <50% of patients (range, 15%–47%; mean, 29%).16,24–27 On the other hand, the main factor limiting the application of SBT is tumor size.7 Thus, the combination of SBT with resection as first-line therapy seems logical.20 Low-grade astrocytomas have a tendency to undergo malignant progression to WHO grade III or grade IV glioma.28 The risk increases with survival time.7 Because tumor tissue or cells left in situ are the main source of malignant tumor recurrence, then high local therapeutic radicality, which can theoretically be increased when resection and SBT are combined, may minimize this particular risk.29

Another argument in favor of integration of SBT into a treatment concept for LGG is the fact that it postpones the use of RT and/or chemotherapy, preserving these measures for recurrent tumors. As shown by the present analysis, individually adopted and repeated application of different treatment options may substantially increase the overall survival rate among patients with LGG.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Funding

No funding for the research.

Acknowledgments

Results were presented as preliminary data at the 59th Annual Meeting of the German Society of Neurological Surgeons (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurochirurgie), Würzburg, 1–4 June 2008.

References

- 1.Norden AD, Wen PY. Glioma therapy in adults. Neurologist. 2006;12(6):279–292. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000250928.26044.47. doi:10.1097/01.nrl.0000250928.26044.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reardon DA, Wen PY. Therapeutic advances in the treatment of glioblastoma: rationale and potential role of targeted agents. Oncologist. 2006;11(2):152–164. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-152. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Bent MJ, Afra D, de Witte O, et al. Long-term efficacy of early versus delayed radiotherapy for low-grade astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma in adults: the EORTC 22845 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9490):985–990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67070-5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watanabe K, Sato K, Biernat W, et al. Incidence and timing of p53 mutations during astrocytoma progression in patients with multiple biopsies. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3(4):523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voges J, Treuer H, Schlegel W, Pastyr O, Sturm V. Interstitial irradiation of cerebral gliomas with stereotactically implanted iodine-125 seeds. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1993;58:108–111. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9297-9_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreth FW, Faist M, Warnke PC, Rossner R, Volk B, Ostertag CB. Interstitial radiosurgery of low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82(3):418–429. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.3.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreth FW, Faist M, Grau S, Ostertag CB. Interstitial 125I radiosurgery of supratentorial de novo WHO Grade 2 astrocytoma and oligoastrocytoma in adults: long-term results and prognostic factors. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1372–1381. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21750. doi:10.1002/cncr.21750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiebert GM, Curran D, Aaronson NK, et al. Quality of life after radiation therapy of cerebral low-grade gliomas of the adult: results of a randomised phase III trial on dose response (EORTC trial 22844). EORTC Radiotherapy Co-operative Group. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(12):1902–1909. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00268-8. doi:10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw E, Arusell R, Scheithauer B, et al. Prospective randomized trial of low- versus high-dose radiation therapy in adults with supratentorial low-grade glioma: initial report of a North Central Cancer Treatment Group/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(9):2267–2276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.126. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.09.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonita R, Beaglehole R. Recovery of motor function after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(12):1497–1500. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.12.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II. Prognosis. Scott Med J. 1957;2(5):200–215. doi: 10.1177/003693305700200504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988;19(5):604–607. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(7):1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wurker M, Herholz K, Voges J, et al. Glucose consumption and methionine uptake in low-grade gliomas after iodine-125 brachytherapy. Eur J Nucl Med. 1996;23(5):583–586. doi: 10.1007/BF00833397. doi:10.1007/BF00833397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treuer H, Kocher M, Hoevels M, et al. Impact of target point deviations on control and complication probabilities in stereotactic radiosurgery of AVMs and metastases. Radiother Oncol. 2006;81(1):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.022. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karim AB, Maat B, Hatlevoll R, et al. A randomized trial on dose-response in radiation therapy of low-grade cerebral glioma: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Study 22844. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;36(3):549–556. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)00352-5. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. doi:10.2307/2281868. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox DR. Regression model and life-tables. J Roy Stat Soc Ser B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawless JF, Singhal K. Efficient screening of non-normal regression models. Biometrics. 1978;34:318–327. doi:10.2307/2530022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schnell O, Scholler K, Ruge M, Siefert A, Tonn JC, Kreth FW. Surgical resection plus stereotactic 125I brachytherapy in adult patients with eloquently located supratentorial WHO grade II glioma - feasibility and outcome of a combined local treatment concept. J Neurol. 2008;255(10):1495–1502. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0948-x. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0948-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pignatti F, van den Bent M, Curran D, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in adult patients with cerebral low-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2076–2084. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.121. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostertag CB, Weigel K, Warnke P, Lombeck G, Kleihues P. Sequential morphological changes in the dog brain after interstitial iodine-125 irradiation. Neurosurgery. 1983;13(5):523–528. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198311000-00007. doi:10.1227/00006123-198311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groothuis DR, Wright DC, Ostertag CB. The effect of 125I interstitial radiotherapy on blood-brain barrier function in normal canine brain. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(6):895–902. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.6.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Veelen ML, Avezaat CJ, Kros JM, van Putten W, Vecht C. Supratentorial low grade astrocytoma: prognostic factors, dedifferentiation, and the issue of early versus late surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64(5):581–587. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.64.5.581. doi:10.1136/jnnp.64.5.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith JS, Chang EF, Lamborn KR, et al. Role of extent of resection in the long-term outcome of low-grade hemispheric gliomas. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1338–1345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9337. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claus EB, Horlacher A, Hsu L, et al. Survival rates in patients with low-grade glioma after intraoperative magnetic resonance image guidance. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1227–1233. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20867. doi:10.1002/cncr.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanai N, Polley MY, Berger MS. Insular glioma resection: assessment of patient morbidity, survival, and tumor progression. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(1):1–9. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohgaki H. Genetic pathways to glioblastomas. Neuropathology. 2005;25(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00600.x. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2004.00600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanai N, Berger MS. Glioma extent of resection and its impact on patient outcome. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(4):753–764. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000318159.21731.cf. discussion 264–756 doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000318159.21731.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]