Abstract

Protein phosphorylation is a well characterized regulatory mechanism in the cytosol, but remains poorly defined in the mitochondrion. In this study, we characterized the use of 32P-labeling to monitor the turnover of protein phosphorylation in the heart and liver mitochondria matrix. The 32P labeling technique was compared and contrasted to Phos-tag protein phosphorylation fluorescent stain and 2D isoelectric focusing. Of the 64 proteins identified by MS spectroscopy in the Phos-Tag gels, over 20 proteins were correlated with 32P labeling. The high sensitivity of 32P incorporation detected proteins well below the mass spectrometry and even 2D gel protein detection limits. Phosphate-chase experiments revealed both turnover and phosphate associated protein pool size alterations dependent on initial incubation conditions. Extensive weak phosphate/phosphate metabolite interactions were observed using non-disruptive native gels, providing a novel approach to screen for potential allosteric interactions of phosphate metabolites with matrix proteins. We confirmed the phosphate associations in Complexes V and I due to their critical role in oxidative phosphorylation and to validate the 2D methods. These complexes were isolated by immunocapture, after 32P labeling in the intact mitochondria, and revealed 32P-incorporation for the α, β, γ, OSCP, and d subunits in Complex V and the 75kDa, 51kDa, 42kDa, 23kDa, and 13a kDa subunits in Complex I. These results demonstrate that a dynamic and extensive mitochondrial matrix phosphoproteome exists in heart and liver.

Keywords: 32P, mitochondria, protein phosphorylation, phosphate-metabolite association, 2D gel electrophoresis, Complex I, Complex V

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation is a major post-translational modification used to acutely regulate the activity and distribution of proteins within the cytosol1. However, in mitochondria the role of protein phosphorylation has been less studied, with the exception of the classical studies on pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)2,3. Several other enzyme systems have been shown to be potentially regulated by phosphorylation, including steps associated with mitochondrial induced apoptosis4, Mn-SOD5 and cytochrome oxidase5–9. Recent screening studies have revealed that the mitochondrial matrix phosphoproteome is much more extensive and complex than previously appreciated; these studies include γ–32P-ATP in isolated potato mitochondria membranes10 and mammalian mitochondria membranes9, Pro-Q diamond staining of mitochondria extracts5,11, isoelectric focusing shift analysis in 2D polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)12, MS/MS screening of phosphorylated peptides in yeast13 and mouse liver14 and 32P inorganic phosphate labeling in intact mitochondria5. Each of these approaches has distinct advantages and disadvantages in screening for protein phosphorylation. While all of these methods have revealed a large number of phosphorylation sites in the mitochondria matrix, the functional significance of the vast majority of these sites remains unknown. 32P labeling has the advantage of monitoring the phosphorylation sites that are turning over and may be more important in acute regulation of metabolism as well as very high sensitivity using the radioisotope readout. Thus, using 32P to establish the dynamics of phosphorylation may provide key insight into the phosphorylation sites that are actively being exchanged or created. The limitation of 32P labeling is related to its high sensitivity; 32P studies can detect metabolite associations as well as very minor phosphorylation/association events that might have minimal biochemical consequences. We report here on studies designed to optimize the in situ detection of matrix protein phosphorylation in the intact mitochondria and compare the labeling patterns in heart and liver mitochondria. The 32P labeling methods were also compared and contrasted to isoelectric focusing and fluorescent dye screening approaches. We then expanded this approach by isolating Complex V and Complex I after the in situ 32P labeling to evaluate the 32P incorporation into these important protein complexes in more detail.

Experimental Procedures

Mitochondrial Isolation and Incubation Conditions

All procedures performed were in accordance with the guidelines described in the Animal Care and Welfare Act (7 U.S.C. 2142 § 13) and approved by the NHLBI ACUC. Pig heart mitochondria were isolated from tissue that was cold-perfused in situ to remove blood and extracellular Ca2+ as well as prevent any warm ischemia as previously described15. One notable modification was that 1 mM K2PO4 was added to buffer A (0.28M sucrose, 10mM HEPES, 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA pH 7.1) for the first re-suspension of the mitochondrial pellets to assure that matrix phosphate depletion was not occurring in the isolation process. Mitochondria were then washed two times with buffer A alone, and finally in buffer B (137mM KCl, 10mM HEPES, 2.5mM MgCl2, 0.5mM K2EDTA). Since minimal exogenous inorganic phosphate (Pi) was used in the labeling experiments, this exposure to 1mM K2PO4 was found necessary to maintain the matrix Pi concentration at levels required to support ATP production (see below). It is important to point out that the trypsin digestion procedure used in this isolation resulted in a mixed population of mitochondria from both sub-sarcolemmal and interfibrillar pools as previously described 5,16.

Pig liver mitochondria were isolated from the same animals as the heart mitochondria following a similar protocol. After euthanasia the liver was removed immediately and flushed through available vessels with 1L of cold buffer A to remove blood. Approximately 250 grams of visually blanched tissue was used for the isolation. After removing fat and connective tissue, liver was finely chopped in 500mL cold buffer A, homogenized two times with a loose fitting tissue grinder, and centrifuged at 600g for 10min at 4°C. The pellet was re-suspended in buffer A and homogenized five times with a tight fitting tissue grinder. This puree was centrifuged at 600g for 10min at 4°C, and the supernatant was immediately centrifuged at 8000g for 10min at 4°C to yield a pellet of mitochondria. Mitochondria were re-suspended in buffer A containing 1mM Pi, washed two times with buffer A in the absence of Pi, and finally washed and re-suspended in buffer B.

Mitochondria preparations were tested for viability by measuring the respiratory control ratio (RCR) by taking the ratio of the rate of oxygen consumption in the presence and absence of ADP (1mM) at 37°C using the following incubation medium: buffer B* (137mM KCl, 10mM HEPES and 2.5mM MgCl2) containing 5mM potassium-Glutamate, 5mM potassium-Malate and 1mM Pi. In addition, the ability to maintain matrix ATP content in the absence of exogenous Pi during warming was evaluated (see below). To accept a mitochondrial preparation, the RCR had to exceed 8 in heart and 5 in liver at 37°C to assure a well coupled system.

Cytochrome a (cyto a) was assayed spectrophotometrically as previously described17. In general experiments were performed with mitochondria protein concentrations of 1 to 2 nmol cyto a/ml in buffer C (125 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5mM potassium-glutamate, 5mM potassium-malate at pH 7.1) at 37°C. Incubations over 5 minutes were supported by passing 100% O2 gas over the incubation medium to assure adequate O2 for oxidative phosphorylation. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay (USB Quant kit, Cleveland, OH).

ATP Assay

ATP assays were conducted after different incubation conditions by taking 1 ml of the suspension and placing it into 2ml of 6% perchloric acid (PCA) on ice. After 10 minutes on ice, the PCA was precipitated using 4M potassium carbonate (~300μL) to titrate to neutral pH. An alkaline overshoot during titration was avoided by adding a universal pH indicator (20μL) directly into the extract and monitoring the pH during the neutralization process. After neutralization the sample was centrifuged and the supernatant collected for ATP analysis. The supernatant was stored at −80°C and analyzed within 48 hours. Total ATP content was determined using a luminescence assay with luciferin–luciferase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), against a standard curve of ATP. Since both the incubation medium and mitochondria were sampled, this assay totaled both matrix and any ATP in the medium.

32P Labeling Experiments

As previously described5 32P was added to energized mitochondria to generate matrix γ-32P-ATP. Briefly, mitochondria (1nmol cyto a/ml) were incubated with 32P in 5 ml of oxygenated buffer C (125 mM KCl, 15 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5mM potassium-glutamate, 5mM potassium-malate at pH 7.1) at 37°C. Incubation was performed in a 50 ml chamber with 100% O2 passed over the top while rocking in a water bath at 37°C. Unless otherwise specified, 250μCi 32P per nmol cyto a was used.

Our initial studies demonstrated that the extent of 32P protein labeling was highly variable. We hypothesized that the level of matrix ATP being generated under conditions of low exogenous phosphate, as used in our 32P labeling protocol, was responsible for the variability. We hypothesized that this variability resulted from inter-preparation differences in the ability of mitochondria to generate matrix ATP. In other words, since our 32P labeling protocol involved low exogenous phosphate, the matrix [ATP] prior to incubation may have been responsible for the variability. To test this hypothesis, matrix [ATP] was measured immediately after isolation and during the 37°C incubation, with glutamate and malate as substrates. We found that the matrix [ATP] was consistently very low after isolation, in agreement with previous studies 18,19, whereas the matrix [ATP] was variable during incubation, in a preparation-dependent manner. In preparations that did not demonstrate robust 32P protein incorporation, the level of ATP did not increase, and sometimes decreased, when incubated at 37°C. In contrast, those preparations where matrix [ATP] increased upon warming a high level of 32P incorporation were generally revealed. Interestingly, the level of matrix ATP recovery was not found to be related to the RCR. In preparations that did not recover [ATP] upon warming, the addition of 1mM inorganic phosphate (Pi) was found to immediately increase ATP content. This result implied that our variability in both matrix [ATP] recovery and 32P labeling resulted from matrix [Pi]. In order to correct for this variability, we briefly incubated mitochondria with 1mM Pi during the isolation process, as outlined in the methods section. The importance of pre-loading with Pi to maintain Kreb’s cycle flux was first acknowledged by Siess et al 20. Using this approach the pattern of 32P incorporation was consistent between preparations. These results emphasize the importance of the mitochondrial energetic state when using this type of 32P labeling protocol.

2D Gel Electrophoresis and Gel Staining

For time course experiments, mitochondrial incubations were stopped immediately by adding an equal sample volume of 10% trichloro-acetic acid (TCA) solution and placing the samples on ice overnight for protein precipitation. The precipitated proteins were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30min at 4°C, and the supernatant was aspirated. The pellet was washed twice with cold 100% acetone, broken apart using a pipette tip and vortexing, and then centrifuged for 15 min in-between wash steps. The pellet was dried and re-suspended in 200μL of lysis buffer containing 15 mM Tris-HCl, 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, and 4% CHAPS (w/v). Protein concentration was determined as described above.

To screen for phosphate-associations, 300μg of cleaned mitochondrial lysate (10ug/ul concentration) was mixed with rehydration solution [7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS (w/v), 13mM DTT, 1% (pH 3-10 NL) Pharmalyte (v/v)] to a final volume of 450uL and placed on ice for 5 min. For difference gel electrophoresis (DIGE), samples were labeled with CyDyes, as previously described12, and then mixed with rehydration solution. Five μL of Destreak reagent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was added to the sample/rehydration solution, vortexed and placed on ice for another 5 min before loading onto a 24 cm Immobiline DryStrip gels (pH 3-10NL) (GE Healthcare). Isoelectric focusing was achieved by active rehydration for 12hr at 30V followed by stepwise application of 250V (1hr), 500V (1hr), 1000V (1hr), gradient to 8000V (1hr) and final step at 8000V (8hr) for a total of ~72,000Vhr (Ettan IPG Phor2, GE).

Immobiline DryStrip gels were equilibrated in 10ml of SDS equilibration solution [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, and 2% SDS] for 10 min, first containing 100 milligrams of DTT and then with 250 milligrams of iodoacetemide. Gel strips were applied to 10–15% SDS-PAGE gels (Jule, Inc., Milford, CT and Nextgen Sciences, Ann Arbor, MI) and sealed with 0.5% agarose containing bromophenol blue. Electrophoresis was performed in an Ettan DALT-12 tank (GE Healthcare) in 20°C electrophoresis buffer consisting of 25mM Tris (pH 8.3), 192mM glycine, and 0.2% SDS until the dye front advanced completely (~2000 Vhr).

In preparation for drying radio-labeled gels, each gel was fixed for 30 min in a 1L solution of 50% methanol and 3% phosphoric acid. Gels were briefly rehydrated with deionized water and placed on filter paper (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) that had been sprayed with deionized water. Gels were then sprayed with deionized water and covered with plastic wrap before placing in a large format dryer (Bio-Rad) for 2h at 70°C under a vacuum. Dried gels were taped in a screen development cassette (GE Healthcare), and exposed to a phosphor-screen (GE Healthcare) for 72 hours.

After electrophoresis, bound 2-D gels were stained with Phos-Tag 540 and destained according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA). Phos-Tag stain is a new phosphoprotein dye that selectively binds to the phosphomonoester residues of phosphoserine, phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine via a charge-based coordination of chelated Zn2+ cations. Following image acquisition (see below), gels were placed in Sypro Ruby protein gel stain (Invitrogen) for overnight staining. The degree of Phos-Tag labeling and background interference was variable between lots, sometimes labeling a majority of subsequently stained Sypro Ruby proteins. To date we have found that NextGen pre-cast Tris-HCl 10–15% gradient gels have the lowest background signal.

Image Acquisition and Analysis

The phosphor-screens were scanned on a Typhoon 9410 variable mode imager (GE Healthcare) at a resolution of 100μm. The scanner was set in phosphor mode with the selection of maximum sensitivity. For Phos-Tag 540 and Sypro Ruby analysis, gels were scanned at a resolution of 100 μm. The excitation was at 532 nm with emission filters of 610BP30 for Sypro Ruby and 560LP for Phos-tag 540.

The 2D images from Ruby, 32P and Phos-tag procedures were aligned using Progenesis SameSpot software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle upon Tyne, U.K.). The Phos-Tag images were generally used to guide picking for protein identification by MS/MS, and these assignments were applied to the 32P gels. Identifications for 32P labeled proteins were confirmed by direct Coomassie G-250 staining of the 32P gels with spatial reference markers containing a mixture of 32P and Cy3 stained protein. In instances when Phos-Tag stained proteins were of low intensity, overlay images from the 32P and Coomassie Blue gels served as a guide for identifying proteins using MS/MS. Ratio intensity analysis was performed with Progenesis PG240 (Nonlinear Dynamics).

Blue- and Ghost-Native Gel Electrophoresis

Native electrophoresis was used to maintain mitochondrial protein complexes in their intact form 21. Standard Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and the colorless Ghost Native PAGE (GN-PAGE) were performed following the methods recently outlined by Blinova et al 22.

Purified Complexes I and V

After incubating intact mitochondria with cold Pi or 32P, as described above, Complexes I and V were isolated using an immunocapture kit (Mitosciences, Eugene, OR), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation, mitochondria were pelleted and solubilized to a final concentration of 5mg/ml in 1x PBS with 1% lauryl maltoside detergent. Mitochondria were then mixed with a pipette and placed on ice for 30min, before spinning down at 10,000 rpm for 30min at 4°C. One ml aliquots of solubilized mitochondrial supernatant were transferred to fresh epindorf tubes containing the following mixture: 5mM potassium-fluoride, 10μl of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 50μl of antibody loaded G-agarose beads. This mixture was allowed to mix overnight at 4°C using a tube rotator. Beads were then washed 3-times in 1x PBS with 0.05% lauryl maltoside, and Complexes I and V were eluted by re-suspending in two volumes of 4M urea, pH 7.5. Purified Complexes I and V were then analyzed by 2D gel electrophoresis as described above or by mass spectrometry as described below.

Protein Identification

For all protein identifications from 2D gels, non-radio-labeled mitochondria were picked using the Ettan Spot Handling Workstation (GE Healthcare)23. Protein identification was carried out using a MALDI-TOF/TOF instrument (4700 Proteomics Analyzer, Applied Biosystems) in positive ion mode with a reflector. For MS analysis, 800–4000m/z mass range was used with 1500 shots per spectrum. Result dependant analysis (RDA) was used for MS/MS selection. A maximum of 6 precursors per protein were selected with a confidence interval (CI) percentage of 50 or higher with a minimum signal/noise ratio of 50. In addition, a low confidence investigation (peptides not matched to top proteins) was used to allow a maximum of 5 precursors per spot with minimum signal/noise ratio of 50 was also selected for data-dependent MS/MS analysis. A 1-kV collision energy was used for collision-induced dissociation (CID), and 1500 acquisitions were accumulated for each MS/MS spectrum. For both MS and MS/MS analysis, the default calibration was calibrated with 4700 mass standard peptide mix (Applied Biosystems) achieving a mass accuracy within 50 ppm. Internal calibration was used for all MS runs using trypsin autolysis peaks 842.51m/z, 1045.56m/z and 2211.11m/z. When one or more of the trypsin peaks were not found within the mass tolerance of 0.1 Da then default processing was used.

The peak-list generating software used was GPS Explorer software, set to default parameters (version 3.0, Applied Biosystems). Mascot search engine was used (version 2.2, Matrix Science, Boston, MA) for peptide and protein identifications. The data searches were performed with the following search parameters: enzyme specificity was set to trypsin, one missed cleavage allowed, fixed modifications for cysteine carbamidomethylation and variable modifications set for methionine oxidation and a mass tolerance of 100 ppm and 0.5 Da was used for precursor ions and fragment ions, respectively. National Center for Biotechnology Information non-redundant database (NCBInr 2008.01.08; 676,132 sequences) was searched against and MS peak filtering was set for all trypsin autolysis peaks. The taxonomy selected was Mammalia (mammals) because the complete pig genome sequence has not been translated and added to NCBI nr database. The number of protein entries searched in the mammalian database is 676,132 out of 5,892,147 total protein entries. The acceptance criteria for individual MS/MS spectra had a significance threshold set to p < 0.05 with expectation values < 0.05 (number of different peptides with scores equivalent to or better than the result reported that are expected to occur in the database search by chance). The p value was chosen to reflect a 95% probability that the protein identification is correct. To eliminate the redundancy of proteins that appeared in the database under different names and accession numbers, the single-protein member belonging to the species Sus scrofa or with the highest protein score (top rank) was singled out from the multi-protein family. Single-peptide-based protein identifications were confirmed by manually inspecting their spectra. In addition, an NCBI BLAST searched was performed for other sequences that may have the same precursor mass. The identifications to single peptides had to meet the following criteria: protein characterized as a mitochondrial protein, E-value less than 0.5, molecular weight and isoelectric point had to match the position where the spot was picked on the 2D gel. The identifications in the Phos-Tag gels were performed on a minimum of 5 animal studies for heart and 3 determinations in liver. Sequence coverage and spectra are presented in the supplemental section.

Results

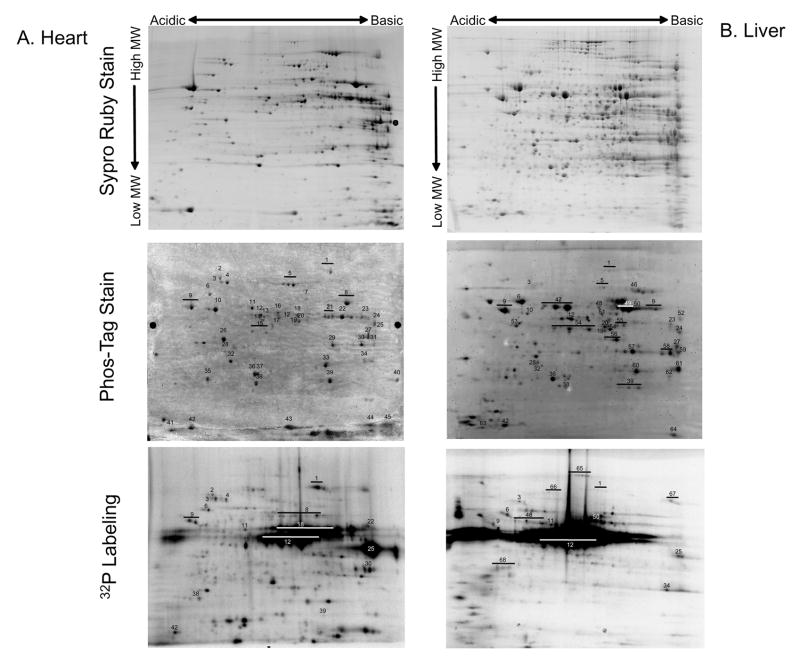

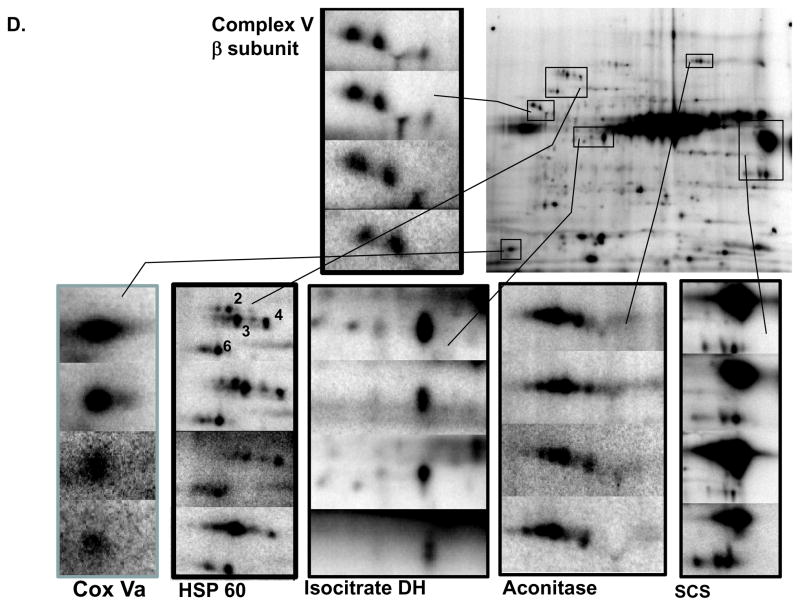

A major focus of the current study was to optimize our 32P labeling protocol for intact mitochondria to further characterize the extent and dynamics of the mitochondrial matrix phosphoproteome. Representative 2D gels of porcine heart and liver mitochondria labeled with Sypro Ruby, Phos-Tag, and 32P are shown in Figure 1. Phosphoprotein identifications were typically obtained directly from the Phos-Tag stained gels using mass spectrometry. In some instances protein identifications were obtained from Coomassie blue stained gels, paired with 32P-labeled gels. Table 1 shows the numbering system legend, which is the same for all figures in this manuscript, unless otherwise specified. A large number of phosphorylated proteins were detected for heart and liver mitochondria using both Phos-Tag and 32P-labeling, with differences in both the relative magnitude of labeling and the labeling pattern. In addition to these phosphoproteomic differences, the DIGE image in Figure 1C showed significant disparity in protein content between heart and liver, consistent with the functionality of mitochondria from different tissues24. The phosphorylation screen identified 68 heart and liver mitochondrial matrix phosphoproteins, from several functional categories, many of which were previously described in heart mitochondria using Pro-Q Diamond staining5,11. Some notable examples include the PDH complex, aconitase, VDAC, Mn-SOD, and several subunits of Complexes I and V (Table 1). Additionally, Phos-Tag staining revealed several novel phosphoproteins, such as thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase in both tissues, isocitrate dehydrogenase in the heart, and ornithine carbamyltransferase and several fatty acid oxidation proteins in the liver.

Figure 1.

The Mitochondrial Phosphoproteome of Porcine Heart and Liver. Representative two-dimensional gels are presented to give total protein (Sypro Ruby), total phosphoproteins (Phos-Tag), and 32P labeling occurring in intact heart (A) and liver (B) mitochondria. Numbers refer to the Phos-Tag stained phosphoprotein identifications presented in Table 1. Not all Phos-Tag stained proteins were identified due to the detection limits of mass spectrometry. Four 32P labeled liver proteins were identified from paired Coomassie blue gels because no Phos-Tag signal was detected. Panel C shows a 2D DIGE gel comparing heart (labeled red, Cy3) and liver (labeled green, Cy5) mitochondria. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150- to 10 kDa. Panel D shows another 2D 32P autoradiogram of heart mitochondria collected in an identical manner as in Figure 1A. Individual panels show replicates from 4 different animals in different regions of the gel to assess reproducibility. Each panel is labeled for the dominate 32P labeled protein in the zoom area. SCS represents Succinyl CoA Synthetase, the numbered regions in the HSP 60 panel as the same as in Figure 1A.

Table 1.

Phosphoprotein identifications for heart and liver mitochondria, corresponding to Figure 1.

Sixty-eight phosphoproteins were identified, and the following columns were used to list the methods of detection: 1) Phos-Tag stained 2D gel - Heart, 2) Phos-Tag stained 2D gel - Liver, 3) 32P labeled 2D gel - Heart, and 4) 32P labeled 2D gel - Liver. The identifications for the 32P labeled gels, were based on corresponding Coomassie images, as mass spectrometry was not conducted on the radioactive gels. From the heart and liver 2D Phos-tag stained gels, 25 phosphoproteins were detected only in the heart, 19 only in the liver gel, and 20 in both gels. Sixteen phosphoproteins were qualitatively detected in the 32P labeled heart gel and 13 in the 32P labeled liver gel, with 5 32P labeled proteins shared between tissues.

| Functional Category | Spot # | Protein Name | NCBI Accession Number | Phos-Tag 2D gel - Heart | Phos-Tag 2D gel - Liver | 32P Labeled 2D gel - Heart | 32P Labeled 2D gel - Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION | |||||||

| Complex I | 2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 1 (75kDa) | 51858651 | * | * | ||

| 13 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 2 (49kDa) | 116242673 | * | ||||

| 17 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1α subcomplex 10 (42kDa) | 464254 | * | ||||

| 32 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 3 (30kDa) | 6166589 | * | * | |||

| 37 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial precursor (24kD) | 128865 | * | ||||

| 35 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 8 (23kDa) | 62287022 | * | ||||

| 44 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) iron-sulfur protein 5 (15kDa) | 3914138 | * | ||||

| Complex II | 5 | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial precusor | 75070503 | * | * | ||

| 61 | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur subunit, mitochondrial precursor | 20455488 | * | ||||

| Complex III | 10 | Ubiquinol-cytochcrome c reductase complex core protein I, mitochondrial precursor | 10720406 | * | * | ||

| 33 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, Rieske iron-sulfur protein precursor | 52001457 | * | ||||

| 45 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex, 14 kDa protein | 136717 | * | ||||

| 41 | Cytochrome b-c1 Complex, subunit 6 | 109940045 | * | ||||

| Complex IV | 42 | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide Va, mitochondrial precursor | 117099 | * | * | * | |

| 43 | Cytochrome c oxidase polypeptide Vb, mitochondrial precursor | 75042739 | * | ||||

| Complex V (FoF1-ATPase) | 8 | ATP synthase, mitochondrial F1 complex, α subunit | 15030240 | * | * | * | |

| 9 | ATP synthase, mitochondrial F1 complex, β subunit | 32189394 | * | * | * | * | |

| 38 | ATP synthase d-chain, mitochondrial precursor | 114686 | * | * | * | ||

| 31 | ATP synthase γ-chain, mitochondrial precusor | 543874 | * | ||||

| 40 | ATP synthase, oligomysin sensitivity-conferring protein | 143811365 | * | ||||

| INTERMEDIARY METABOLISM | |||||||

| Krebs Cycle | 1 | Aconitase hydratase, mitochondrial precursor | 113159 | * | * | * | * |

| 21 | Citrate synthase, mitochondrial precursor | 116470 | * | ||||

| 12 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, E1α subunit | 448580 | * | * | * | ||

| 26 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, E1β subunit | 116242689 | * | ||||

| 4 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, E2 subunit | 3915777 | * | * | |||

| 46 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP), mitochondrial precursor | 52783203 | * | ||||

| 23 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase (NADP-dependent) | 462384 | * | * | |||

| 15 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase (NAD) subunit alpha, mitochondrial precursor | 68565369 | * | * | |||

| 27 | Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | 2506849 | * | * | |||

| 16 | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase E1 component αchain | 129030 | * | ||||

| 25 | Succinyl-CoA ligase (GDP-forming) alpha-chain, mitochondrial precursor | 8134728 | * | * | * | ||

| 53 | Succinyl-CoA ligase (GDP-forming) beta-chain, mitochondrial precursor | 21264506 | * | ||||

| 14 | Succinyl-CoA ligase (ADP-forming) beta-chain, mitochondrial precursor | 21263966 | * | ||||

| 11 | Dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex | 18203301 | * | * | * | ||

| Cysteine Metabolism | 24 | Aspartate aminotransferase, mitochondrial precursor | 112985 | * | * | ||

| 57 | Thiosulfate sulfurtransferase, mitochondrial precursor | 1174694 | * | ||||

| Fatty Acid Oxidation | 52 | Trifunctional enzyme subunit beta, mitochondrial precursor | 6015048 | * | |||

| 67 | Trifunctional enzyme subunit alpha, mitochondrial precursor | 7387634 | * | ||||

| 54 | Short-branched chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SBCAD) | 75060971 | * | ||||

| 20 | Long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD) | 2829676 | * | * | |||

| 55 | Medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) | 148872486 | * | ||||

| 19 | Short-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (SCAD) | 13878316 | * | * | |||

| 60 | Short chain enoyl-CoA hydratase | 119119 | * | ||||

| 59 | 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase, mitochondrial precursor | 3913456 | * | ||||

| 62 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase type-2 | 3183024 | * | ||||

| 58 | D-beta-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | 25108876 | * | ||||

| Urea Cycle | 56 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase, mitochondrial precursor | 3183093 | * | |||

| 65 | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase I, mitochondrial precursor | 117492 | * | ||||

| Amino Acid Metabolism | 34 | Electron transfer flavoprotein, β subunit | 75053043 | * | * | ||

| 49 | Glutamate dehydrogenase 1, mitochondrial precursor | 118541 | * | * | |||

| 68 | 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | 122135732 | * | ||||

| ANTIOXIDANT | |||||||

| 39 | Mn superoxide dismutase | 134677 | * | * | * | ||

| 36 | Thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase, mitochondrial precursor | 2507170 | * | * | |||

| TRANSPORT | |||||||

| 30 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 1 | 10720225 | * | * | |||

| 29 | Voltage-dependent anion channel 2 | 75050405 | * | ||||

| 63 | Mitochondrial import inner membrane translocase, subunit Tim8A | 90101777 | * | ||||

| OTHER | 6 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial precursor | 51702252 | * | * | * | * |

| 3 | 70kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial precursor | 14917005 | * | * | * | * | |

| 64 | 10 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | 47606335 | * | ||||

| 22 | Creatine kinase, sarcomeric mitochondrial precursor | 68052065 | * | * | |||

| 51 | Glycine amidinotransferase | 1730202 | * | ||||

| 28 | Prohibitin | 464371 | * | * | |||

| 47 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase class 2, mitochondrial precursor | 118502 | * | * | |||

| 48 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 7, member A1 | 109940193 | * | ||||

| 50 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase, mitochondrial precursor | 6226865 | * | ||||

| 18 | Elongation factor Tu, mitochondrial precursor | 1352352 | * | * | |||

| 7 | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | 118675 | * | ||||

| 66 | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase alpha chain, mitochondrial precursor | 6174892 | * | ||||

In Figure 1D, the reproducibility of the 32P labeling in the heart mitochondria is demonstrated. In this figure another 2D gel from a separate animal is presented along with representative examples from the beta subunit of Complex V, the HSP 70 region, Aconitase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and VDAC region. These are from different sectors of the gel, with each image representing a study from a different animal. The variability was highest in proteins with isoelectric variants consistent with some differential labeling rates, however, the relative labeling positions were very consistent between experiments.

Given the extreme sensitivity and dynamic nature of 32P, the potential for large variability in these types of studies is significant. In order to optimize our 32P labeling protocol for extent and consistency, the most favorable experimental conditions had to be established, including: 1) 32P dosing and 2) time-course of labeling. Dosing studies at 1, 25, 50, and 250μCi 32P per nmol cyto a revealed dose-dependent labeling (results not shown). Since the 250μCi dose revealed the greatest number of phosphoproteins, with the highest resolution, this dose was used for most studies. This dose often resulted in saturation of those proteins that labeled intensely, such as PDH E1α and succinyl CoA synthetase, α-subunit. If studies were conducted to specifically study these proteins, then the 50μCi dose was used.

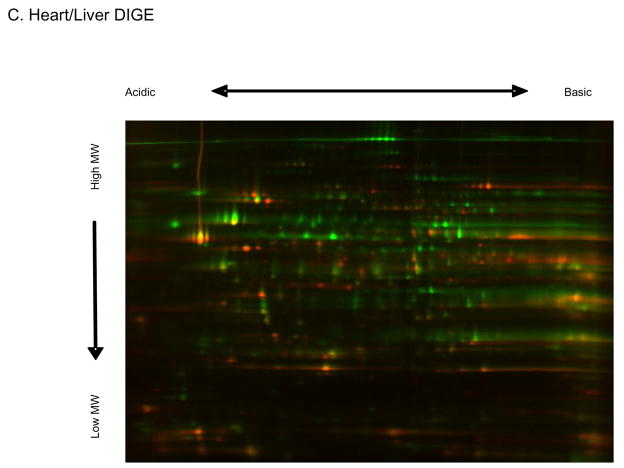

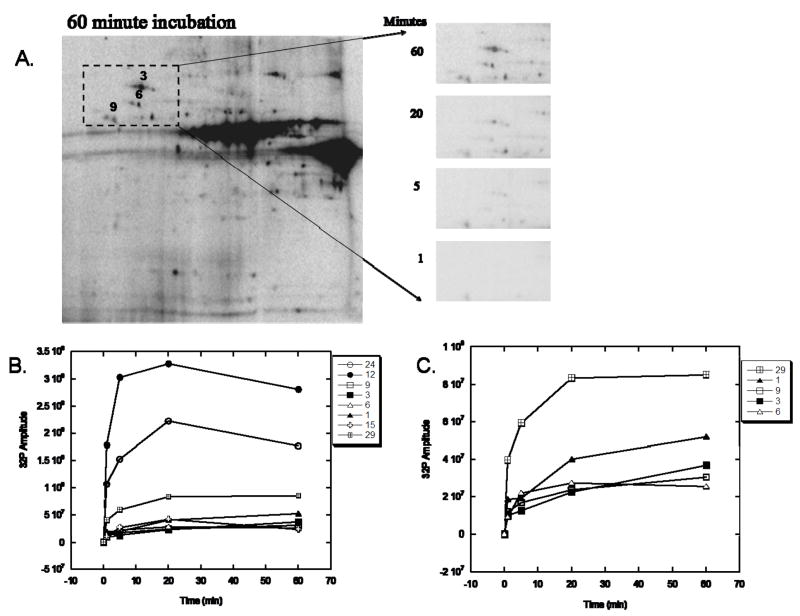

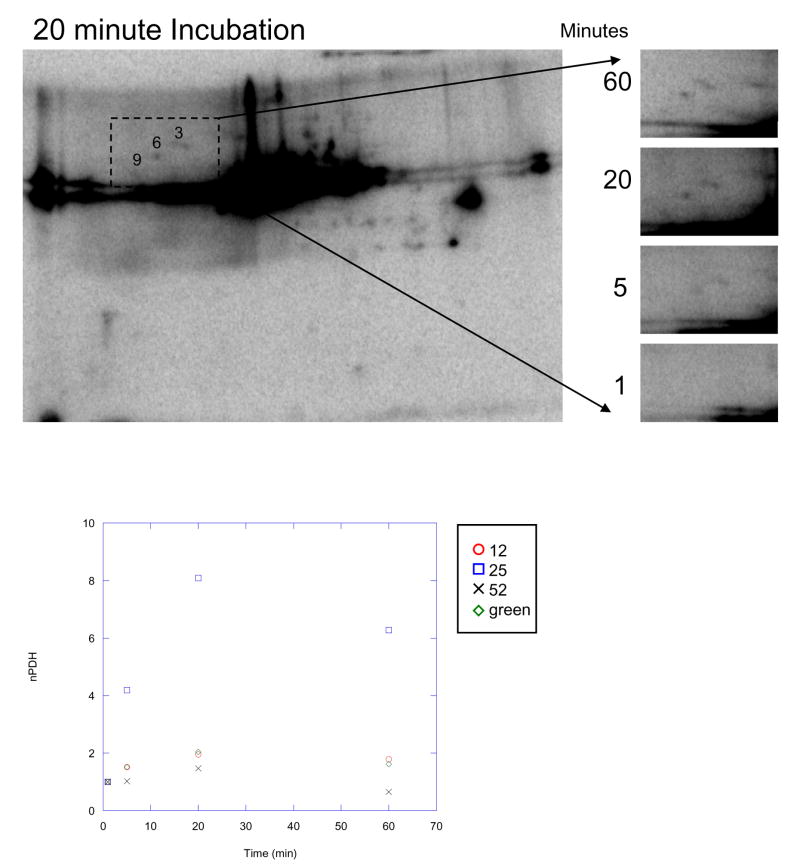

A major benefit of direct 32P labeling is the ability to track the kinetics of phosphorylation, i.e., the rapid turnover rate of 32P incorporation into proteins. In order to optimize our labeling protocol, the kinetics of 32P incorporation were studied by adding 32P to intact heart (Figure 2) and liver (Figure 3) mitochondria and taking TCA-quenched samples at 1, 5, 20, and 60 min. These time-course studies revealed that a majority of proteins rapidly increased 32P incorporation until about 20min, and then slightly increased, decreased or plateau. Figures 2A and 3 qualitatively demonstrate the kinetics of 32P incorporation into mitochondrial proteins using 2D gel electrophoresis, whereas Figures 2B–C provide a quantitative analysis of the relative 32P incorporation into select heart proteins at each time-point. Based on these data, our experiments were conducted at the 20 min time point, where optimal 32P incorporation occurred for most proteins. Notably, the extent of 32P-incorporation into a majority of liver mitochondrial proteins is considerably less than that of heart proteins. PDHE1α is an exception, apparently labeling much more intensely with 32P in liver than in heart, despite slightly higher protein content in heart 25.

Figure 2.

Time-Course Experiments of 32P Labeling in Heart Mitochondria. A) Time course of 32P labeling in heart mitochondrial proteins using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Expansion of the selected region at 1, 5, 20, and 60 minutes demonstrates enhanced labeling of Complex V, β-subunit (protein 9), heat shock protein 60 (protein 6), and heat shock protein 70 (protein 3) with time. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa. Panel B shows the relative amplitude of 32P labeling, as a function of time, for several identified proteins. Proteins with lower, relative 32P labeling are expanded in Panel C. The protein numbers correspond to those presented in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Time-Course Experiments of 32P Labeling in Liver Mitochondria using Two-Dimensional Gel Electrophoresis. Expansion of the selected region at 1, 5, 20, and 60 minutes demonstrates enhanced labeling of Complex V, β-subunit (protein 9), heat shock protein 60 (protein 6), and heat shock protein 70 (protein 3) with time. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa. The protein numbers correspond to those presented in Table 1.

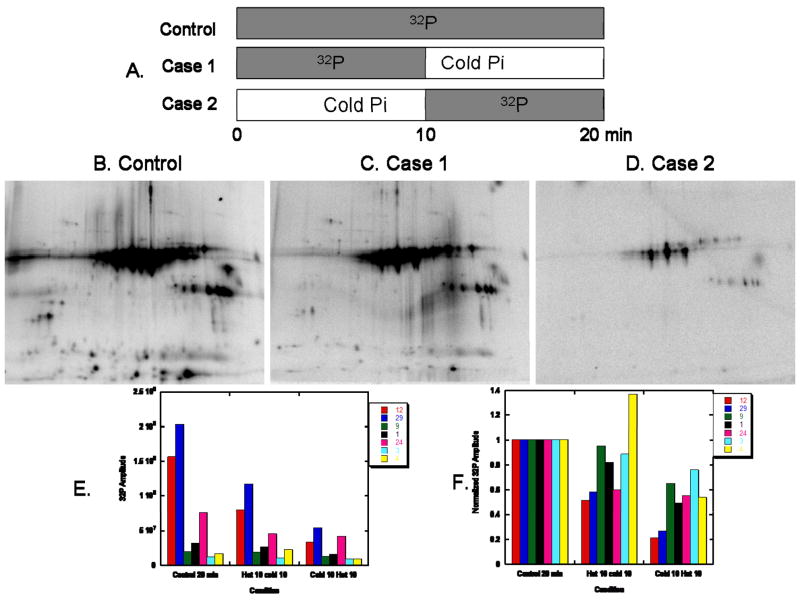

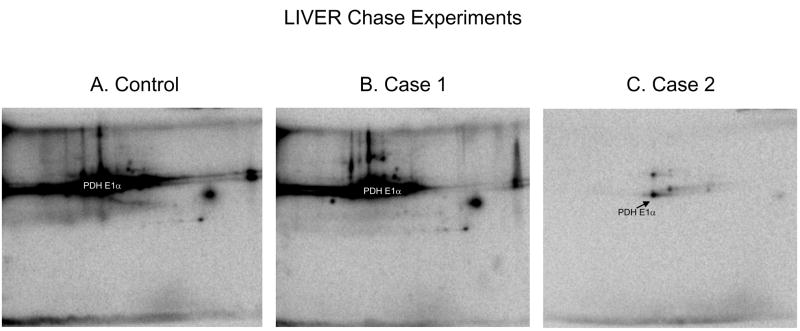

Although 32P labeling of a protein is often attributed to rapid phosphate exchange, several proteins, namely PDHE1α 18,26, demonstrated strong 32P incorporation as a means of rebuilding the phosphate pool size upon warming and re-energizing the mitochondria. In other words, strong 32P labeling may result from the restoration of a protein’s native, steady-state phosphorylation status following mitochondrial isolation, and not phosphorylation site turnover alone. In attempt to resolve the contribution of turnover rate and phosphate pool size alterations to the overall 32P labeling pattern, we designed a series of chase experiments, as outlined in Figure 4A. In Case 1 the initial 32P label was added for 10min and then chased with excess Pi (2mM) for an additional 10min to determine what degree of 32P incorporation resulted from phosphate pool re-building. In Case 2 excess Pi was added for 10min and then chased with 32P for an additional 10min to establish what extent of 32P incorporation was reversible, and therefore the result of a rapid turnover rate. The control phosphor-images for heart and liver mitochondria, consisting of 32P labeling for 20min, are shown in Figures 4B and 5A, respectively. As seen in the phosphor-images for Case 1 (Figures 4C and 5B), a majority of the 32P labeling was not reversed by the addition of excess Pi. Of further interest are the select Case 1 proteins in both tissues that increased 32P labeling, relative to the control experiment, after the addition of cold Pi. The reason that these proteins increase 32P incorporation is currently unknown, but may be related to the changes in ATP content or energization state that occurs with the addition of Pi 27. The phosphor-images for Case 2 (Figures 4D and 5C) demonstrated that an initial incubation with 2mM Pi substantially decreased the 32P labeling pattern. These results revealed that for both tissues a majority of phosphate incorporation occurred early in the re-energization process, most likely to restore the native phosphorylation status for those proteins de-phosphorylated during the isolation process. Notably, PDH E1α demonstrated strong phosphate-pool rebuilding, especially in the liver. The intense pool rebuilding for liver PDHE1α was often a complication, since it resulted in saturation before the exposure of other 32P-labeled liver proteins could be visualized. A quantitative summary of the chase experiments for heart mitochondria is presented in Figures 4E–F.

Figure 4.

32P Chase Experiments in Heart Mitochondria. A) Schematic Diagram of the 3 conditions used. Panels B, C, and D show the two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of heart proteins at the end of each of the three cases. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa. The incubation conditions are outlined in the Methods section. The lower panels illustrate the raw (E) and normalized (F) 32P labeling amplitude of several indentified proteins after each incubation case. The protein numbers correspond to those presented in Table 1.

Figure 5.

32P Chase Experiments in Liver Mitochondria. Panels A, B and C show the two-dimensional gel electrophoresis of liver proteins at the end of each of the three cases, outlined in Figure 4A. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa.

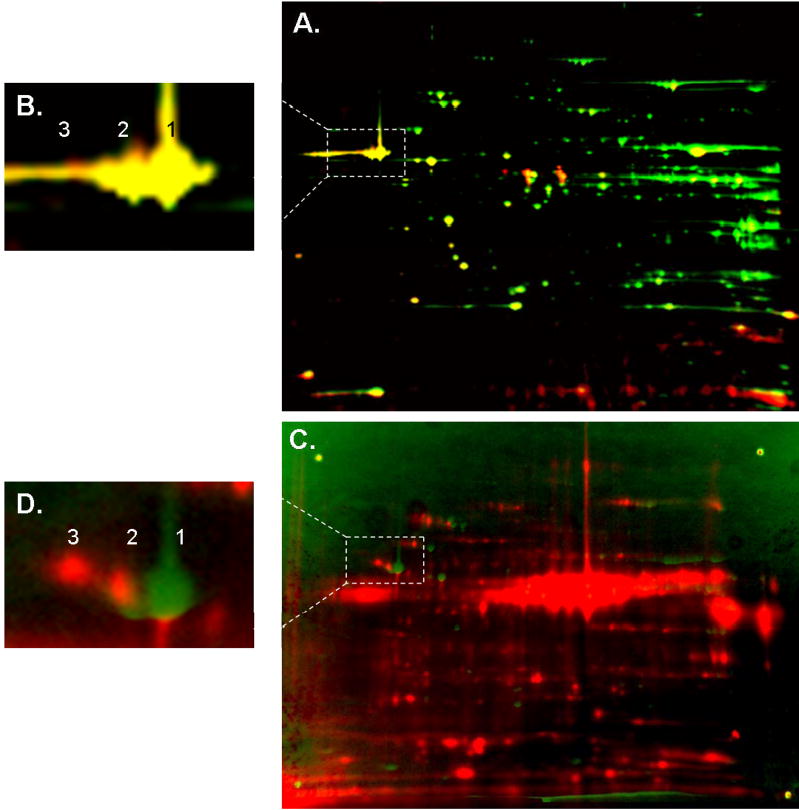

It is generally assumed that the different isoelectric focused elements of a given protein, isoelectric-variant (IEV), are due to post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, glycosylation, ADP ribosylation, oxidation, etc. To better understand the nature of both Phos-Tag and 32P incorporation into the different IEVs of heart and liver mitochondria, warped overlays of the 32P labeled images with the Coomassie stained images as well as Phos-Tag with Sypro Ruby were performed using spatial reference markers (Figures 6 and 7). All overlays were performed on the same gel. The overlays of Phos-Tag and Sypro Ruby (Figures 6A and 7A) generally revealed a good correlation between Phos-Tag labeling and a protein’s IEVs. Some examples include Complex V α and β subunits, aconitase, succinate dehydrogenase, and Mn-SOD. A majority of proteins revealed high Phos-Tag binding in the most alkaline IEV (i.e. parent protein), suggesting that all forms of the protein were phosphorylated. In both heart and liver mitochondria, Phos-Tag staining of PDHE1α was very intense, revealing an abundant, steady-state phosphorylated component for this protein. In the 32P-Coomassie overlays (Figures 6C and 7B–C), a large number of phosphorylated proteins were revealed. Although good correlation between 32P and Coomassie staining was revealed for several acidic heart and liver proteins (i.e., Complex V, β-subunit and heat shock proteins 60 and 70), many 32P incorporation sites did not overlay with any Coomassie stained proteins. This result underlines the fact that 32P is much more sensitive in detecting phosphoproteins than conventional protein stains. Due to a lack of sufficient protein, we were unable to directly identify most of these sites using mass spectrometry. In addition, several proteins revealed 32P labeling that did not coincide with their Coomassie stained IEVs. A notable pattern involved an increasing molecular weight shift of a protein’s 32P labeled component, with little or no direct labeling of its IEVs. Such an upward shift is clearly demonstrated for the β subunit of Complex V (Figure 6D). The amount of protein in these molecular weight shifted 32P labeled components was below detection in the Coomassie stained gels and subsequent MS identification. However, purified protein studies revealed the same labeling pattern, supporting the identification of these 32P sites as the β subunit (see below). This labeling pattern implied that a significant increase in molecular weight was associated with the 32P label, suggesting that either ATP or ADP binding could be involved with Complex V’s β subunit. Notably, this increasing molecular weight shift was not observed in the Phos-Tag stained gel (Figure 6B). The overlays of 32P and Coomassie staining generally revealed that 32P incorporated into the far acid-shifted IEVs of the protein. Aconitase in the heart and carbomyl-phosphate synthase in the liver provide good examples of this behavior.

Figure 6.

Overlay of Heart Mitochondria Protein Content with 32P labeling and Phos-Tag staining. A) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis overlay of Sypro Ruby stained (green) and Phos-Tag labeled (red) porcine heart mitochondria. B) The expansion of Complex V, β-subunit from Panel A. C) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis overlay of Coomassie stained (green) and 32P labeled (red) porcine heart mitochondria, based on 4 spatial reference markers. Although several 32P-labeled proteins correspond to Coomassie stained spots, many proteins detected with 32P were not detected with Coomassie, resulting in a predominance of pure red spots. Such proteins lack in total protein content, and therefore identification by mass spectrometry analysis failed to yield results. D) The β-subunit of Complex V reveals an increasing molecular weight shift of the protein’s 32P labeled component relative to its Coomassie stained IEVs. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa. The relative amplitude for each image was arbitrarily set.

Figure 7.

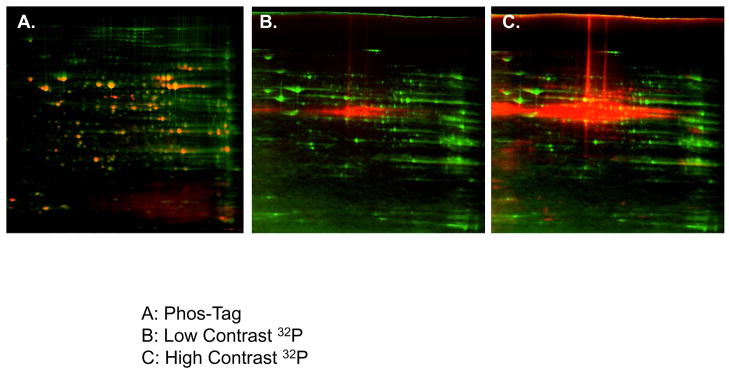

Overlay of Liver Mitochondria Protein Content with 32P labeling and Phos-Tag staining. A) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis overlay of Sypro Ruby stained (green) and Phos-Tag labeled (red) porcine liver mitochondria. B) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis overlay of Coomassie stained (green) and low-contrast 32P labeled (red) porcine liver mitochondria, based on 4 spatial reference markers. C) Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis overlay of Coomassie stained (green) and high-contrast 32P labeled (red) porcine liver mitochondria, based on 4 spatial reference markers. The intense 32P labeling of PDHE1α results in saturation before a majority of the other 32P labeled liver proteins can be visualized. Proteins are separated in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa. The relative amplitude for each image was arbitrarily set.

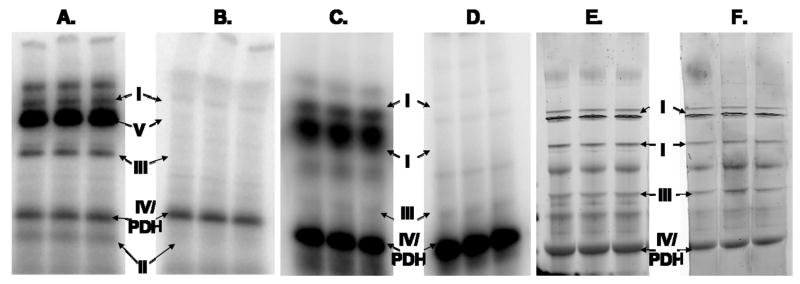

Another approach to mitochondrial protein isolation is blue/ghost native gel electrophoresis, where the major complexes of oxidative phosphorylation can be observed in nearly intact form 21. Both Phos-Tag and 32P labeled heart mitochondrial protein samples were evaluated using these approaches. A 1D blue native gel of 32P labeled mitochondria, demonstrated 32P-association for all five complexes of oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 8A). Protein assignments were again obtained by MS of samples taken from paired gels. Interestingly, when a paired 32P labeled gel was exposed to denaturing conditions (i.e., washed with an acid solution of 50% methanol, 10% acetic acid), 32P labeling was significantly decreased for all five complexes, most notably Complex V (Figure 8B). Removal of the 32P label implied a weak association of phosphate/phosphate metabolites (ATP, ADP, etc.) to the protein complexes in their native state. Phos-Tag analysis was not attempted in 1D blue native gels due to the optical interference from the blue native dye. Instead, Phos-Tag staining of ghost native gels was used to evaluate steady-state phosphate associations for mitochondrial proteins in their native form. Ghost native gel electrophoresis does not capture Complex II or Complex V as distinct bands, but does detect Complexes I, III and IV. Phos-Tag stained ghost native gels were not sensitive to washing with acid (Figures 8E–F); however, as observed in the blue native gels, 32P-association for the protein complexes in ghost-native gels was sensitive to acid washing (Figures 8C–D). Together, these native gel results implied that the complexes of oxidative phosphorylation have abundant, but weak phosphate/phosphate-metabolite associations (Figures 8A–D) as well as substantial steady-state phosphorylations (Figures 8E–F).

Figure 8.

One-dimensional Native PAGE of 32P and Phos-Tag Labeled Proteins from Porcine Heart Mitochondria. Blue Native PAGE of 32P labeled mitochondrial proteins with (B) and without (A) acid washing. Ghost-Native PAGE of 32P labeled mitochondrial proteins with (D) and without (C) acid washing. Ghost-Native PAGE of Phos-Tag stained mitochondrial proteins with (F) and without (E) acid washing. Ghost-Native PAGE was used to avoid the interference of the intense blue color of the Coomassie dye used in Blue Native Gels.

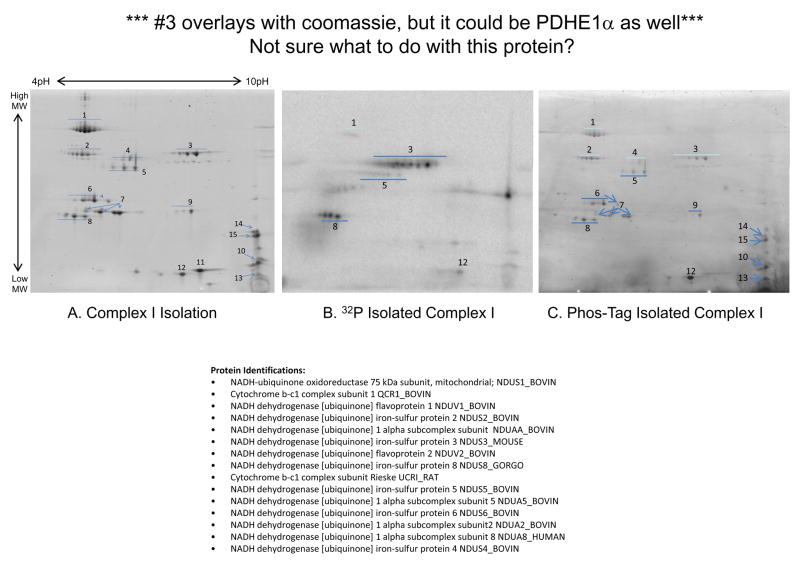

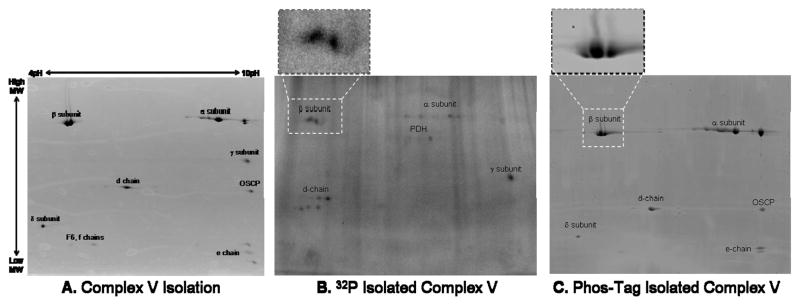

Given the overall importance of Complexes V and I as regulators of oxidative phosphorylation and the potential implications of their phosphorylation status, the remainder of this manuscript focused on characterizing the dynamics of phosphorylation for these enzyme complexes. Isolating Complex V (Figure 9A–C) and Complex I (Figure 9D–F) provided confirmation for their various 32P labeled subunits in the more complex gels, and provided a better understanding of the contribution of phosphate and other phosphate-metabolites to their overall labeling patterns. For example, the overlay image in Figure 6 revealed that the 32P labeled components of Complex V’s β-subunit increased in molecular weight relative to their Coomassie stained protein elements. To investigate this finding further, we isolated Complex V with high purity (Figure 9A) from intact porcine heart mitochondria labeled with 32P (Figure 9B). This result confirmed the identity of these upward-shifted 32P labeled proteins as the β-subunit. In addition this Complex V isolation demonstrated 32P labeling of the α–, γ–, and d-chain subunits. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report phosphorylation for the d-chain subunit. Even though the Coomassie image and an LC-MS/MS analysis revealed no PDHE1α contamination, the 32P labeled image contained some PDHE1α, which was not surprising given the extreme sensitivity of 32P and the intense PDHE1α labeling in these intact mitochondria studies. Phos-Tag staining of isolated Complex V showed labeling of the α–, β–, δ–, d-chain, OSCP, and e-chain subunits (Figure 6C). Unlike the 32P image, the Phos-Tag stained image revealed no molecular weight shift for the β-subunit, suggesting abundant, steady-state phosphorylation.

Figure 9.

Phosphate Labeling of Purified Complex V and Complex I from Porcine Heart Mitochondria. Panel A shows the two-dimensional gel profile of Complex V stained with Sypro Ruby, with subunit identifications obtained by mass spectrometry. Panels B and C show 32P labeled and Phos-Tag stained Complex V, respectively, with expansion of the β-subunit. Panel D shows the two-dimensional gel profile of Complex I stained with Sypro Ruby, with subunit identifications obtained by mass spectrometry. Panels E and F show 32P labeled and Phos-Tag stained Complex I, respectively. Complex I protein identifications are provided in Table 2. Proteins were separated by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, first in the horizontal direction by isoelectric focusing point (pI), from pH ~4 to 10, and then vertically by molecular weight, from ~150 to 10 kDa.

Complex I is the largest enzyme in the respiratory chain, with an estimated 45–46 subunits28–32, several of which have recently been shown to be phosphorylated 8,33–41. Isolating Complex I from porcine heart mitochondria resolved 13 subunits (Figure 9D). A substantial number of the Complex I subunits are of low molecular weight (i.e., below 10kDa), which is below the level of detection on this 2D gel. Isolating Complex I from intact porcine heart mitochondria labeled with 32P (Figure 9E) revealed 32P incorporation for the 75kDa, 51kDa, 42kDa, 23kDa, and 13a kDa subunits. Strong 32P labeling was also observed for a basic protein, with a molecular weight between 30 and 40kDa; however, due to a lack of sufficient protein, we were unable to identify this protein with mass spectrometry. Phos-Tag staining of purified Complex I (Figure 9F) also revealed labeling for several subunits, including the 75kDa, 51kDa, 49kDa, 42kDa, 30kDa, 24kDa, 23kDa, 19kDa, 18kDa, 15kDa, 13a kDa, and 8B subunits. To the best of our knowledge, several of these subunits represent potential novel phosphorylation site (Table 2). Notably, the 51kDa and 13a kDa subunits, which label strongly with 32P and Phos-Tag, have not been described as phosphoproteins.

Table 2.

Purified Complex I identifications, corresponding to Figure 9.

Thirteen Complex I subunits were identified by mass spectrometry from Sypro Ruby stained gels. Twelve of these subunits labeled with Phos-Tag and 5 labeled with 32P. Seven of these Complex I phosphoproteins have not been previously reported. References for the subunits that have been shown to be phosphorylated are listed below the table.

| Spot # | Protein Name | NCBI Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| CI-75kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75kDa subunit [4] | 128825 |

| CIII-1 | Cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 | 10720406 |

| CI-51kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 51kDa subunit | 548387 |

| CI-49kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 49kDa subunit [7] | 116242673 |

| CI-42kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 42kDa subunit [5,6,8] | 464254 |

| CI-30kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 30kDa subunit [3] | 146345462 |

| CI-24kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 24kDa subunit | 128865 |

| CI-23kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 23kDa subunit [1] | 115502490 |

| CIII-IX | Cytochrome b-c1 complex Rieske | 52001457 |

| CI-19kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 19kDa subunit | 1171870 |

| CI-18kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 18kDa subunit [2,9] | 400578 |

| CI-15kD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 15kDa subunit | 400587 |

| CI-13akD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 13kDa, a subunit | 1709407 |

| CI-13bkD | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 13kDa, b subunit | 400650 |

| CI-B8 | NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase B8 subunit | 400515 |

Dai J, Jin WH, Sheng QH, Shieh CH, Wu JR, Zeng R. Protein phosphorylation and expression profiling by Yin-yang multidimensional liquid chromatography (Yin-yang MDLC) mass spectrometry. 6. 2007;J Proteome Res:250. doi: 10.1021/pr0604155.

De RD, Panelli D, Sardanelli AM, Papa S. cAMP-dependent protein kinase regulates the mitochondrial import of the nuclear encoded NDUFS4 subunit of complex I. Cell Signal. 2008;20:989. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.01.017.

Huang SY, Tsai ML, Chen GY, Wu CJ, Chen SH. A systematic MS-based approach for identifying in vitro substrates of PKA and PKG in rat uteri. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2674. doi: 10.1021/pr070134c.

Kim SC, Chen Y, Mirza S, Xu Y, Lee J, Liu P, Zhao Y. A clean, more efficient method for in-solution digestion of protein mixtures without detergent or urea. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3446. doi: 10.1021/pr0603396.

Palmisano G, Sardanelli AM, Signorile A, Papa S, Larsen MR. The phosphorylation pattern of bovine heart complex I subunits. Proteomics. 2007;7:1575. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600801.

Pocsfalvi G, Cuccurullo M, Schlosser G, Scacco S, Papa S, Malorni A. Phosphorylation of B14.5a subunit from bovine heart complex I identified by titanium dioxide selective enrichment and shotgun proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:231. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600268-MCP200.

Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y, Hu Y, Tan Z, Stokes M, Sullivan L, Mitchell J, Wetzel R, Macneill J, Ren JM, Yuan J, Bakalarski CE, Villen J, Kornhauser JM, Smith B, Li D, Zhou X, Gygi SP, Gu TL, Polakiewicz RD, Rush J, Comb MJ. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025.

Schilling B, Aggeler R, Schulenberg B, Murray J, Row RH, Capaldi RA, Gibson BW. Mass spectrometric identification of a novel phosphorylation site in subunit NDUFA10 of bovine mitochondrial complex I. FEBS Lett. 2005. p. 2485.

Tao WA, Wollscheid B, O'Brien R, Eng JK, Li XJ, Bodenmiller B, Watts JD, Hood L, Aebersold R. Quantitative phosphoproteome analysis using a dendrimer conjugation chemistry and tandem mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2005;2:591. doi: 10.1038/nmeth776.

Discussion

This study used Phos-Tag staining and 32P labeling of porcine heart and liver mitochondria to further characterize the extensive network of mitochondrial phosphoproteins established in previous gel-based screening studies5,6,10,11. Figure 1 showed that a large number of mitochondrial phosphoproteins were detected with both Phos-Tag and 32P labeling. Since Phos-Tag stains the steady-state phosphate incorporation into proteins, whereas highly sensitive 32P labeling is dependent on phosphate turnover rate and pool building, different labeling patterns were observed for these techniques in both heart and liver mitochondria. The inconsistencies revealed from comparing these two techniques have provided insight into the feasibility of using each methodology as well as the inherent characteristics of the heart and liver mitochondrial phosphoproteomes.

The number of reported mitochondrial phosphoproteins has grown extensively. Mass spectrometry studies13,14 have revealed that most phosphoproteins contain multiple phosphorylations, resulting in hundreds of new phosphorylations sites. Importantly, there is good correlation between these mass spectrometry results and phosphoproteins identified from 2D gels labeled with 32P or phospho-specific dyes5,6,10,11. With these hundreds of phosphorylation sites, we suggest that determining the turnover of these sites using 32P will identify the dynamic phosphorylation sites that may represent acute regulatory sites that warrant further attention. Thus, a major focus of this study was to optimize the 32P labeling methodology in intact mitochondria to better characterize the biochemistry associated with 32P-protein associations.

In order to achieve reproducible 32P labeling patterns, the importance of maintaining matrix [ATP] was determined. Independent of whether the mitochondria held a membrane potential, exhibited a strong RCR or showed an appropriate net state 3 rate, the matrix [ATP] upon warming and re-energization was found to be critical for reproducible 32P labeling patterns. The major variable in this process was matrix [Pi], which was depleted in our isolation procedures, but was replenished adequately by a brief Pi incubation during the isolation process.

The dynamic nature of 32P incorporation is an advantage, but also a complication, as outlined in the time-course and chase experiments. If 32P association resulted solely from rapid turnover, then the extent of labeling would be relatively independent of the order of additional 32P and cold phosphate. However, the majority of 32P labeling was not exchanged out by a cold Pi chase. A good example of this was PDHE1α, which remained heavily phosphorylated after the cold Pi chase in both heart and liver mitochondria. This data are consistent with the de-phosphorylation of PDH during the mitochondrial isolation process, followed by a re-phosphorylation with warming and de-energization, as demonstrated in earlier functional studies from Randle’s lab18. Several other phosphoproteins revealed this pattern of non-exchanging pools, including VDAC1 and elongation factor, tau in the heart and electron transfer flavoprotein, β-subunit and serine hydroxymethyl-transferase in the liver. In the heart experiments, Succinyl-CoA Synthetase, α-subunit and the 23kDa subunit of Complex I were exceptions; these proteins did significantly exchange out 32P implying a rapid exchange of phosphate. These chase experiments demonstrated that 32P incorporation into proteins was not merely the result of rapid phosphate exchange, but also due to the recovery of phosphorylated protein pools upon re-energization.

Using both Phos-Tag staining and 32P labeling provided specific information on the nature of the phosphate-protein association. Good correlation of 32P and Phos-Tag provided evidence that the degree of phosphorylation was significant with a significant turnover, or pool expansion. Examples of strong labeling with both 32P and Phos-Tag in heart and liver mitochondria include PDHE1α, heat shock proteins 60 and 70, aconitase, and Complex V, β-subunit PDH E2, VDAC1, Complex I 23kDa subunit, aconitase and Complex IV Va subunit (Figures 1, 6 and 7).

Several proteins exhibited high 32P labeling with low Phos-Tag staining, suggesting a rapid turnover into a fraction of the phosphorylation sites or simply a low total abundance of the protein (Figures 1, 6 and 7). These two conditions can be differentiated using the total protein stains. For example, succinyl-CoA synthetase, α-subunit, γ subunit of Complex V, and aconitase in the heart and carbamoyl-phosphate synthase and 3-hydroxy-isobutyrate dehydrogenase in the liver all exhibited strong 32P labeling and relatively weak Phos-Tag staining. However, the total protein levels suggested that the lack of Phos-Tag labeling in succinyl-CoA synthetase and 3-hydroxy-isobutryate dehydrogenase was consistent with low protein content. In contrast, the significant amount of aconitase and carbamoyl-phosphate synthase protein suggested a low overall percentage of steady-state phosphorylation, with a relatively high turnover. Another explanation for high 32P incorporation and low Phos-Tag labeling may also be ascribed to proteins undergoing 32P metabolite associations, and not protein phosphorylation (discussed below). Such 32P associations include enzyme catalytic sites that retain high affinity, even in the presence of denaturing SDS.

Another labeling pattern involved strong Phos-Tag staining, but weak 32P incorporation (Figures 1, 6 and 7). This result suggested that a protein was abundantly phosphorylated in steady-state, but that its phosphate turnover rate was relatively slow in the 20min time-course of these experiments. This behavior was demonstrated in both heart and liver mitochondria by Mn-SOD, Complex I 30kDa subunit, succinate dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit, and thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase. Interestingly, the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex E1α (BCKDH) labeled strongly with Phos-Tag in heart, but was not detected with 32P staining, as has been previously demonstrated42,43. Given the proximity of BCKDH to the strongly 32P labeled elongation factor, Tu and PDH E1α, it is likely that BCKDH’s 32P labeling may be masked in our 2D gel studies.

Additionally, many proteins showed strong 32P labeling in regions where no Phos-Tag or total protein stain was observed. This pattern suggested a very high specific activity and turnover rate for these low abundant proteins. In general, these proteins were not identified in this study due to their low concentration and the limits of our mass spectroscopy identification. The unidentified 32P labeled proteins deserve further investigation, since they may represent signaling molecules that are in low concentration in order to permit rapid changes in phosphorylated protein levels during signaling processes.

There were also some interesting discrepancies between 32P incorporation, Phos-Tag and IEV elements within given proteins. For many proteins, 32P preferentially incorporated into the far acid shifted IEVs, while Phos-Tag stained all IEV elements, including the most alkaline, parent IEV (Figures 6 and 7). 32P labeling of the most acidic IEV species implied that the turnover rate of the acid shifted IEVs were much higher than the alkaline IEVs species. Examples of this behavior are observed in heart and liver mitochondria for heat shock protein 70 and aconitase, and in the purified protein studies for the α- and d-chain subunits of Complex V and the 51kDa subunit of Complex I (Figure 9). The reason for high phosphate turnover in the acidic IEV species is unknown and not predicted by conventional interpretation of the IEV phenomenon being simple summing of individual post-translational modifications.

Another discrepancy between 32P labeling and Phos-Tag within a protein involved an increased molecular weight shift of a protein’s 32P labeled component, relative to its Phos-Tag or total protein stain. An example of this was Complex V’s β-subunit, which showed 32P labeling well above its Coomassie stained IEVs (Figure 6D), but Phos-Tag staining on all components, including the parent protein IEV (Figure 6B). Comparing the Phos-Tag and 32P labeling patterns of Complex V suggested that a large fraction of the β-subunit had steady-state phosphorylation, while a small component of the protein experienced very rapid phosphate exchange with slightly higher molecular weight incorporation, consistent with metabolite-binding such as ATP or ADP. Since sites of phosphorylation have been identified for Complex V’s β-subunit using mass spectrometry44, these sites most likely represent the abundant, steady-state phosphorylations depicted using Phos-Tag. The increasing molecular weight shift of the 32P labeled components of Complex V’s β-subunit was evaluated further in an isolated protein study, which is discussed below.

Comparing the phosphoproteomes of heart and liver mitochondria (Figure 1) revealed that 32P labeling is generally weaker in liver mitochondria relative to heart, with the exception of PDHE1α. The DIGE image presented in Figure 1C demonstrates that there are differences in protein content between tissues, consistent with the notion that mitochondria are fine tuned to the functionality of a given tissue24. However, these differences in protein content cannot alone explain the radical differences in 32P incorporation between heart and liver mitochondria. Interestingly, proteins associated with energy-metabolism (i.e., aconitase, Complex IV, Va subunit, and Complex V, α- and β-subunits) are labeled much more intensely with 32P in the heart, whereas proteins involved in biosynthetic processes (i.e., carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, aldehyde dehydrogenase and 3-hydroxy-isobutyrate dehydrogenase) incorporate 32P intensely in the liver. Whether phosphorylation is regulated in a tissue-specific manner to meet the different metabolic demands of heart and liver mitochondria is relatively unknown and requires further investigation.

Utilizing minimally disruptive native gel electrophoresis, we observed that a large fraction of the 32P association was removed upon denaturing with heat or acid (Figure 8). For example, Complex V had the most intense 32P labeling in the native gels. However, upon denaturing, the 32P labeling of this band was dramatically reduced to a level consistent with that observed in our 2D gel studies, which denature proteins with SDS. This pattern held true for all five complexes of oxidative phosphorylation, and suggested that many mitochondrial protein complexes have a high degree of weak, phosphate-metabolite interactions in their native form. These weak associations may be related to active enzyme sites or allosteric binding sites on individual proteins or within protein complexes. Furthermore, these associations potentially provide a mechanism for phosphate/phosphate-metabolites to modulate oxidative phosphorylation at several levels, as has been suggested in previous studies for Complex IV45,46 and, naturally, Complex V which uses these metabolites in its catalytic activity (discussed in more detail below). Thus, the native gel system may provide an extremely useful tool in screening for weak, phosphate-metabolite interactions that may regulate enzyme activities. It is important to note that Phos-Tag labeling in ghost native gels was considerably less sensitive to washing with acid (Figure 8E–F), implying that this approach primarily detected abundant, steady-state phosphoproteins and not the weak interactions observed with 32P labeling.

Although this study aimed to screen for mitochondrial protein phosphorylation, the native gel studies (discussed above) and the purified protein studies (discussed below) clearly demonstrate that phosphate-metabolites are formed and likely contribute to the overall 32P labeling pattern observed in our 2D gel studies. The binding of phosphate-metabolites may be responsible for the 32P labeled components that increase in molecular weight above a given protein’s Coomassie stained IEVs. In addition to the formation of radioactive ATP and ADP upon the incubation of intact mitochondria with 32P, several other metabolites may form in the 20min time-course of our experiments and result in additional covalent protein modifications, such as ADP-ribosylation. Interestingly, the biosynthesis of NAD in mitochondria is on the order of minutes47. Furthermore, nicotinamide monoculceotide adenylyltransferase-3 (NMNAT3), a central enzyme of NAD biosynthesis, is localized to the mitochondria48. Thus, while the majority of 32P labeling observed in our 2D gel studies is likely due to phosphorylation, the contribution of phosphate-metabolites is possible and will require further study.

We focused on Complexes V and I to confirm identifications of their 32P-labeled subunits in the more complex gels and to better characterize the nature of these Complex’s phosphate-associations. Phos-Tag staining of purified Complex V revealed labeling of the α, β, δ, d, OSCP, and e-chain subunits (Figure 9C). Good correlation between Phos-Tag labeling and total protein IEVs with modest, implied that these proteins are abundantly phosphorylated. 32P association was found in α, β, γ, and d-chain subunits (Figure 9B) suggesting these elements have rapidly exchanging protein phosphorylation sites. Since the purified 32P labeled components of the β-subunit are shifted in molecular weight above its IEVs (as observed in the total protein study; Figure 6D), this supports the notion that the 32P labeled protein originates from Complex V, and is most likely an ATP or ADP association. Our observation that the β-subunit labels in intact mitochondria in the presence of oligomycin (results not shown) suggests that this labeling may primarily result from ADP incorporation. The minute fraction of the β-subunit involved in this binding may represent the active catalytic sites or other metabolite association sites. Purified Complex V was also used to confirm identification of the far acid-shifted 32P components of the α- and d-chain subunits in the more complex 2D gel studies. As observed for several matrix proteins, this acid-shifted 32P incorporation pattern indicates that a tiny fraction of the α- and d-chain subunits exchange phosphate rapidly, whereas Phos-Tag labeling on the most alkaline components of these proteins suggests that a large steady state fraction is phosphorylation. Thus far the role that phosphorylation may play in the regulation of Complex V’s activity has yet to be resolved. However, these studies imply that phosphorylation of the γ-subunit may be the most interesting with regards to the extent of its 32P label and its reported sensitivity to dephosphorylation with calcium5.

Purifying Complex I from porcine heart mitochondria resulted in the identification of 13 subunits (Figure 9D). Although Complex I 45–46 subunits29,49–52, previous studies in bovine heart have demonstrated that 26 of these subunits migrate on SDS gels in the molecular weight range of 10–20kDa29,53,54, which is below the level of detection in our system. Phos-Tag staining of purified Complex I (Figure 9F) revealed labeling for the 75kDa, 51kDa, 49kDa, 42kDa, 30kDa, 24kDa, 23kDa, 19kDa, 18kDa, 15kDa, 13a kDa, and 8B subunits. As observed in the total protein study, this purified Complex I study revealed good correlation between the Phos-Tag staining and the total protein IEVs, implying abundant steady-state phosphorylation. To the best of our knowledge, 7 of these Phos-Tag labeled subunits are novel phosphorylations, including the 51kDa, 24kDa, 19kDa, 15kDa, 13a kDa, 13b kDa, and B8 subunits. Although the nature of phosphorylation for Complex I’s 18kDa subunit is still a matter of debate11,55–63, our purified study demonstrates good resolution and strong Phos-Tag labeling for the 18kDa subunit, consistent with it being phosphorylated in steady-state. 32P incorporation was observed in the 75kDa, 51kDa, 42kDa, 23kDa, and 13a kDa subunits. 32P incorporation into 51kDa and 42kDa subunits was partially masked by the proximity of PDHE1α. However, 32P incorporation was observed for the far acid-shifted IEVs of the 51kDa protein, suggesting that a relatively small fraction of the protein is turning over rapidly. Although the exact role that phosphorylation may play in regulating Complex I remains largely elusive, studies have demonstrated that mutations disrupting phosphorylation sites in specific Complex I subunits (i.e., 18kDa64,65) can result in lethal phenotypes. To this effect, phosphorylation of the 51kDa may be the most interesting because it labels intensely with 32P, carries the NADH-binding site66, has a high degree of conservation—underlining its functional importance67, and its mutation has specifically been implicated in several clinical ailments68.

Conclusion

This study builds on previous studies5,6,10–12 to further define the extent and nature of the mitochondrial phosphoproteome. Using Phos-Tag staining and 32P labeling revealed that protein phosphorylation was found in all of the metabolic and functional pathways of porcine heart and liver mitochondria. Comparing Phos-Tag staining and direct 32P labeling revealed numerous advantages and limitations of these approaches in screening the phosphoproteome. In general, 32P incorporation was extremely useful for monitoring the dynamics of protein-phosphate association in the mitochondria. Purified protein studies on the 32P labeled subunits of Complexes I and V confirmed the identification of these subunits in the total protein gel studies and revealed several novel phosphorylated subunits, which may have regulatory implications. However, the high sensitivity of 32P labeling resulted in detection of potentially minor phosphorylation events as well as residual phosphate metabolite association that may have questionable biochemical importance. Related to this was the demonstration of abundant, but weak phosphate metabolite associations in several complexes of oxidative phosphorylation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilsa Rovira for providing guidance and oversight of the radioisotope studies and Dr. Toren Finkel for the laboratory space. These studies were funded by the Division of Intramural Research.

Abbreviations

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- AMP

Adenosine monophosphate

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BN-PAGE

Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- Cyto a

Cytochrome a

- GN-PAGE

Ghost native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- IEV

Isoelectric variant

- KCl

Potassium chloride

- MgCl2

Magnesium chloride

- MnCl2

Manganese chloride

- Mn-SOD

Manganese superoxide dismutase

- NaCl

Sodium chloride

- OSCP

Oligomycin sensitivity conferring protein

- PCA

Perchloric acid

- PDH

Pyruvate dehydrogenase

- Pi

Inorganic phosphate

- RCR

Respiratory control ratio

- TLC

Thin layer chromatography

- TGS

Tris-Glycine-SDS

- Tris-HCl

Trishydroxymethylaminomethane-hydrochloric acid

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Division of the NHLBI and NIH grant DK47844 (RH)

Reference List

- 1.Cohen P. The origins of protein phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(5):E127–E130. doi: 10.1038/ncb0502-e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linn TC, Pettit FH, Reed LJ. Alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. X. Regulation of the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from beef kidney mitochondria by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;62(1):234–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linn TC, Pettit FH, Hucho F, Reed LJ. Alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. XI. Comparative studies of regulatory properties of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes from kidney, heart, and liver mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;64(1):227–234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L) Cell. 1996;87(4):619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopper RK, Carroll S, Aponte AM, Johnson DT, French S, Shen RF, Witzmann FA, Harris RA, Balaban RS. Mitochondrial matrix phosphoproteome: effect of extra mitochondrial calcium. Biochemistry. 2006;45(8):2524–2536. doi: 10.1021/bi052475e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bykova NV, Egsgaard H, Moller IM. Identification of 14 new phosphoproteins involved in important plant mitochondrial processes. FEBS Lett. 2003 ;540(1–3):141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang JK, Prabu SK, Sepuri NB, Raza H, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Galati D, Spear J, Avadhani NG. Site specific phosphorylation of cytochrome c oxidase subunits I, IVi1 and Vb in rabbit hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(7):1302–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sardanelli AM, Technikova-Dobrova Z, Scacco SC, Speranza F, Papa S. Characterization of proteins phosphorylated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase of bovine heart mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1995;377(3):470–474. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steenaart NA, Shore GC. Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV is phosphorylated by an endogenous kinase. FEBS Lett. 1997;415(3):294–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Struglics A, Fredlund KM, Konstantinov YM, Allen JF, Moller IM. Protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in the inner membrane of potato tuber mitochondria. FEBS Letters. 2000;475(3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01680-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulenberg B, Aggeler R, Beechem JM, Capaldi RA, Patton WF. Analysis of steady-state protein phosphorylation in mitochondria using a novel fluorescent phosphosensor dye. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(29):27251–27255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schieke SM, Phillips D, McCoy JP, Jr, Aponte AM, Shen RF, Balaban RS, Finkel T. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(37):27643–27652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinders J, Wagner K, Zahedi RP, Stojanovski D, Eyrich B, van der LM, Rehling P, Sickmann A, Pfanner N, Meisinger C. Profiling phosphoproteins of yeast mitochondria reveals a role of phosphorylation in assembly of the ATP synthase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(11):1896–1906. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700098-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(5):1488–1493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609836104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.French SA, Territo PR, Balaban RS. Correction for inner filter effects in turbid samples: fluorescence assays of mitochondrial NADH. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(3 Pt 1):C900–C909. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.3.C900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lesnefsky EJ, Moghaddas S, Tandler B, Kerner J, Hoppel CL. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac disease: ischemia--reperfusion, aging, and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33(6):1065–1089. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balaban RS, Mootha VK, Arai AE. Cytochrome oxidase determination in the presence of myoglobin or hemoglobin contamination. Analytical Biochemistry. 1996 doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerbey AL, Randle PJ, Cooper RH, Whitehouse S, Pask HT, Denton RM. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase in rat heart. Mechanism of regulation of proportions of dephosphorylated and phosphorylated enzyme by oxidation of fatty acids and ketone bodies and of effects of diabetes: role of coenzyme A, acetyl-coenzyme A and reduced and oxidized nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide. Biochem J. 1976;154(2):327–348. doi: 10.1042/bj1540327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitehouse S, Cooper RH, Randle PJ. Mechanism of activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase by dichloroacetate and other halogenated carboxylic acids. Biochem J. 1974;141(3):761–774. doi: 10.1042/bj1410761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siess EA, Kientsch-Engel RI, Fahimi FM, Wieland OH. Possible role of Pi supply in mitochondrial actions of glucagon. Eur J Biochem. 1984;141(3):543–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]