Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a phosphorylation- and ATP-regulated anion channel. CFTR expression and activity is frequently associated with an anion exchanger (AE) such as AE2 coded by the Slc4a2 gene. Mice null for Cftr and mice null for Slc4a2 have enamel defects, and there are some case reports of enamel anomalies in patients with CF. In this study we demonstrate that both Cftr and AE2 expression increased significantly during the rat enamel maturation stage versus the earlier secretory stage (5.6- and 2.9-fold, respectively). These qPCR data im- ply that there is a greater demand for Cl– and bicarbonate (HCO3–) transport during the maturation stage of enamel formation, and that this is, at least in part, provided by changes in Cftr and AE2 expression. In addition, the enamel phenotypes of 2 porcine models of CF, CFTR-null, and CFTR-ΔF508 have been examined using backscattered electron microscopy in a scanning electron microscope. The enamel of newborn CFTR-null and CFTR-ΔF508 animals is hypomineralized. Together, these data provide a molecular basis for interpreting enamel disease associated with disruptions to CFTR and AE2 expression.

Key Words: Cystic fibrosis, Dental, Enamel, Hydroxyapatite

Introduction

Many diseases and multiple organ pathologies are directly related to abnormalities in pH regulation [Lacruz et al., 2010a]. These may result from mutations in genes encoding anion transporters and channels. Two examples of such diseases are proximal renal tubular acidosis caused by SLC4A4 mutations and cystic fibrosis (CF) caused by CFTR mutations [reviewed in Lacruz et al., 2010a]. SLC gene products that are expressed in ameloblasts include AE2 and NBCe1 encoded by SLC4A2 and SLC4A4, respectively [Lyaruu et al., 2008; Paine et al., 2008; Lacruz et al., 2010b]. AE2 and CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) are frequently coexpressed in cells where passive movement of Cl– into, and out of, cells is required [Shumaker et al., 1999; Banales et al., 2008]. AE2 is an anion exchanger (HCO3– and Cl–), and mice null for the Slc4a2 gene have abnormal enamel [Gawenis et al., 2004; Lyaruu et al., 2008]. Mutations to CFTR also result in dental and enamel anomalies. Data from the Cftr-null mouse [Snouwaert et al., 1992] suggest that disruptions to Cftr activity impacts on the enamel phenotype [Wright et al., 1996; Sui et al., 2003], and in a human population there are documented case reports that have identified such a relationship [Narang et al., 2003; Azevedo et al., 2006; Atar and Korperich, 2010].

One method to determine which ion transport genes are important in enamel development is to investigate the relative expression of these genes during the secretory and maturation stages of enamel. During the transition from secretion to maturation extracellular pH markedly decreases, increasing the requirements for maintaining an acid-base balance by ameloblast cells [Smith, 1998; Lacruz et al., 2010a]. Transgenic and knockout animal models of ion transport genes allow the classification of an enamel phenotype without confounding factors, such as antibiotic use. In this paper we investigate the expression of AE2 and CFTR in amelogenesis using a rat model. We then highlight the enamel phenotype of targeted CFTR-null and CFTR-ΔF508 mutations in a novel porcine animal model [Rogers et al., 2008; Stoltz et al., 2010].

Materials and Methods

Animals

All vertebrate animal manipulation complied with Institutional and Federal guidelines.

Rat Tissue Dissection

Adult male Wistar Hannover rats weighting 170–190 g were euthanized, and their mandibles were immediately dissected out; the surrounding soft tissues were removed, and the mandibles were then frozen in liquid nitrogen as previously described [Smith et al., 2006]. Mandibles were kept in liquid nitrogen overnight and the samples were then lyophilized for 24 h. The mandibular bone encasing the lower incisors was carefully removed to expose the entire labial surface. The enamel organ cells were then collected via gentle scraping from 3 different regions of the incisor. A molar reference line was used to isolate cells from secretory, early-mid maturation, and mid-late maturation stages following the method previously described by Smith and Nanci [1989] but adapted here for rats weighing 170–190 g.

Total RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted by homogenizing the freeze-dried enamel organ cells from each of the 3 zones using a Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit. Reverse transcription PCR was performed using an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR (qPCR) reactions were performed with iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) using the primer pairs shown in table 1. Primer pairs were designed to span intronic regions and are the rat equivalent to either human or mouse primer pairs identified in ‘PrimerBank’ as ideal for qPCR (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/index.html). The relative expression of mRNA was calculated using the delta-delta CT method [Livak and Schmittgen, 2001]. All values for the mRNA species were normalized to β-actin.

Table 1.

Rat-specific qPCR primers

| Protein/gene | GenBank reference | Forward primer | Sequence | Reverse primer | Sequence | Product size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actb (Actb) | NM_031144 | rActb.f | 5'AGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGTA | rActb.r | 5'GCCAGGGCAGTAATCTCCTTCT | 112 |

| Enam (Enam) | NM_017468 | rEnam.f | 5'TGCAGAAATACAGCTTCTCCT | rEnam.r | 5'CATTGGCATTGGCATGGCA | 105 |

| Odam (Odam) | NM_001044274 | rOdam.f | 5'ATCAATTTGGATTTGTACCACA | rOdam.r | 5'CGTCGGGTTTATTTCAGAAGTGA | 242 |

| AE2 (Slc4a2) | NM_017048 | rAE2.f | 5'AGCCCATCTCCCCCTACAC | rAE2.r | 5'AAGGTTGTAACTTCGATGTCCAG | 186 |

| Cftr (Cftr) | NM_031506 | rCftr.f | 5'CTGGACCACACCAATTTTGAGA | rCftr.r | 5'GCGTGGATAAGCTGGGGCT | 162 |

All primer pairs span intron sequences, and only single products were produced during qPCR.

Backscattered Electron Imaging of Porcine Incisors

The crowns of 4 lower left deciduous 3rd incisors (Di3) of newborn wild-type pigs, 4 of CFTR-ΔF508, and 4 of CFTR-null animals [Rogers et al., 2008; Stoltz et al., 2010] were embedded in polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) resin and cut with a diamond band saw at a point below the cusp tip to produce representative cross sections of the fully mature enamel. Each PMMA block was subsequently polished to a 1-μm surface finish and acid etched (37% phosphoric acid) for 3 s. Specimens were washed, air dried, and imaged at variable pressure (50 Pa) using a Zeiss EVO-50 in backscattered electron microscopy in a scanning electron microscope (BSE-SEM) imaging mode at 20 kV, 400 pA, and a 10-mm working distance without a conductive coating. The electron beam was confirmed stable after 30 min of operation and, when possible, BSE detection, contrast, and brightness were arbitrarily set to conditions that contained both specimens within a broad 0–255 grey dynamic range for semiquantitative comparison. When mineralization density differences were too large to be sensibly contained within the full dynamic range, representative images were acquired for illustrative purposes. Grey-level images were subject to an 8-bit color look-up table for visual comparison of differences in mineralization density between samples. Two sets of comparisons were performed using color-coded images; wild-type pig deciduous incisors were independently compared to CFTR-null and CFTR-ΔF508 animals.

Results

Confirmation of Dissection Accuracy by Defining Stages of Amelogenesis Using Enamel-Specific Gene Transcripts

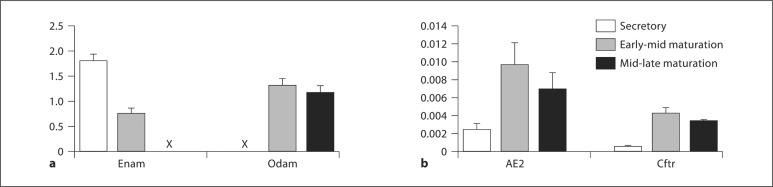

Total RNA was prepared from enamel organ epithelial cells (primarily ameloblasts and also associated papillary layer cells) from male Wistar Hannover rats. Two gene transcripts (Enam and Odam) shown in many studies to have expression patterns essentially limited to ameloblasts were chosen to assess the accuracy of the dissections by defining 3 distinct stages of amelogenesis, i.e. secretory, early-mid maturation, and mid-late maturation, in rodents. Enam is a product of secretory- and early-maturation stage ameloblasts, and its expression is low or not apparent during late-maturation stages of amelogenesis [Hu et al., 2000]. Odam is a product of maturation stage ameloblasts, and its expression is low or not apparent during secretory-stage amelogenesis [Moffatt et al., 2008]. All data were normalized to β-actin (Actb). Our initial results confirmed that we had accurately dissected these 3 stages of amelogenesis by confirming and characterizing expected Enam and Odam mRNA expression profiles (fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Transcript analysis for Enam and Odam (a) and AE2 and Cftr (b). a Levels of Enam during secretory-stage amelogenesis and Odam levels in maturation-stage amelogenesis are of the same order of magnitude as Actb. The X indicates that the measurements are present; however, the magnitude and standard error are bars not clearly apparent in the scale of this graph. b Note that the relative levels of AE2 and Cftr are of 2 orders of magnitude less than seen for Actb, Enam, and Odam. When comparing mid-late maturation stage amelogenesis to secretory-stage amelogenesis there was a significant upregulation of AE2 mRNA (2.9-fold) and Cftr mRNA (5.6-fold). All mRNA transcript levels were normalized to those of β-actin (represented on the y-axis).

Upregulation of AE2 and Cftr Is Clearly Apparent as Cells Transition from Their Secretory-Stage to Early-Mid Maturation Stage Amelogenesis, and Higher Levels Are Maintained during Enamel Maturation

AE2 and Cftr expression levels are shown for the 3 stages of amelogenesis (fig. 1b). When comparing mid-late maturation stage amelogenesis to secretory-stage amelogenesis there was significant upregulation of AE2 mRNA (2.9-fold) and Cftr mRNA (5.6-fold). Our results confirm previous findings that AE2 and Cftr are expressed in enamel organ cells during amelogenesis and are upregulated as enamel matures [Lyaruu et al., 2008; Bronckers et al., 2010]. The increased expression of AE2 and Cftr during enamel maturation highlights the greater requirement for ameloblast HCO3– and Cl– transport at this later stage of enamel development.

CFTR-Null and CFTR-ΔF508 Animals Have Hypomineralized Enamel

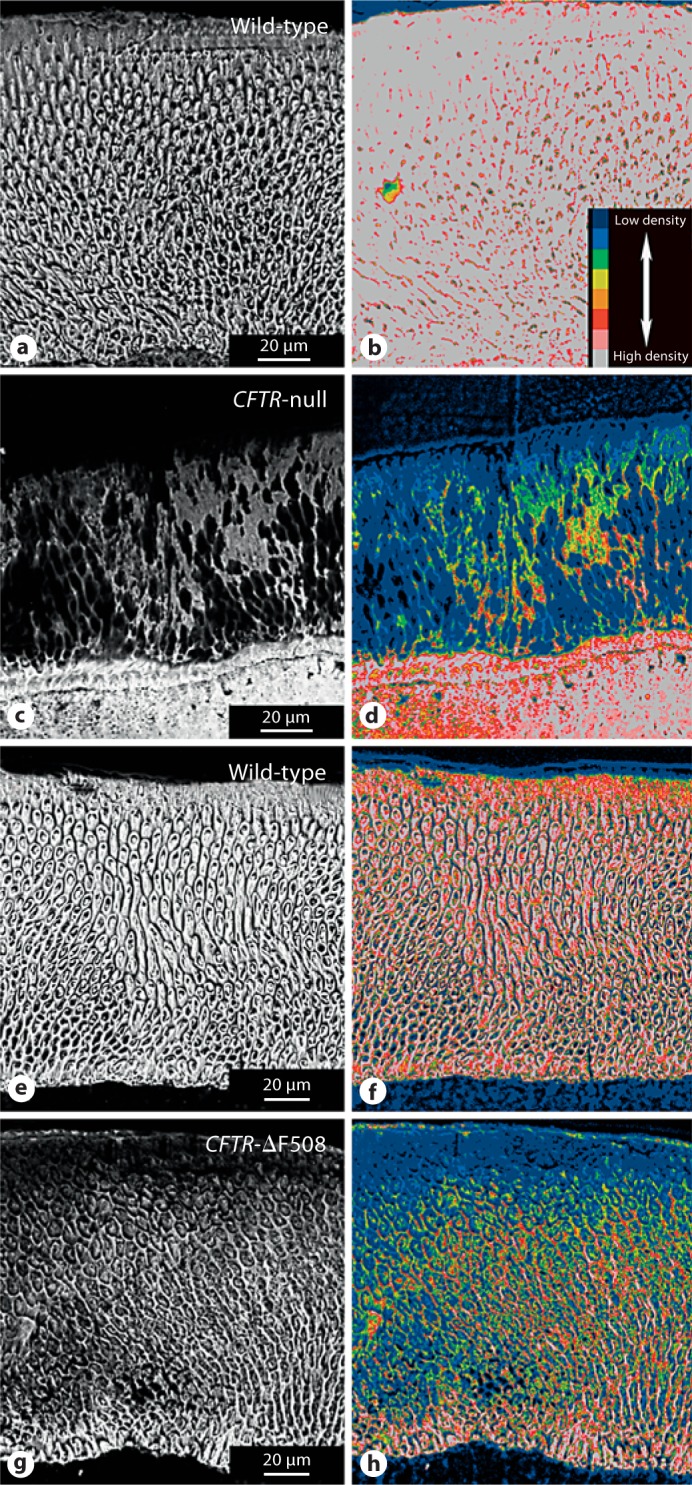

The analysis of pig mandibular Di3 by BSE-SEM imaging is shown in figure 2. BSE-SEM images (fig. 2a, c, e, g) show details of enamel microstructure and density signals, whereas the other images (fig. 2b, d, f, h) are the corresponding color-coded images used to assess differences in mineralization. Overall, both CFTR-ΔF508 and CFTR-null animals show hypomineralized enamel when compared to wild-type animals. Figure 2 shows differences in enamel microstructure and thickness between wild-type (fig. 2a) and CFTR-null (fig. 2c) animals. The original BSE-SEM images of wild-type animals obtained under the same conditions as those used to image the CFTR-null animals are not shown because of the extreme density (brightness) of the enamel in the former; the image brightness and contrast of the wild type (fig. 2a) were reduced relative to the CFTR-null animal (fig. 2c) to efficaciously illustrate details of the microstructure. CFTR-null animals (fig. 2c) revealed altered enamel microstructure and were hypomineralized; remarkably, their dentine was more electron dense than the enamel. Color-coded images (fig. 2b, d) of figure 2a, c, respectively, illustrating differences in mineralization. A comparison between wild-type and CFTR-ΔF508 animals, respectively, is shown (fig. 2e, g). Figure 2g reveals that CFTR-ΔF508 enamel is hypomineralized compared to the wild type. Corresponding color-coded images are shown in figure 2f (wild type) and figure 2h (CFTR-ΔF508) also illustrating density differences.

Fig. 2.

BSE imaging of enamel of porcine CFTR animals. Wild-type (a) and CFTR-null enamel (c) comparisons illustrate a severe morphological defect in the null animal. Signal intensity was reduced in the wild-type relative to the null animal to lower the image content out of white (255 grey level) into interpretable morphological details. Wild-type (e) and CFTR-ΔF508 (g) enamel comparisons; both images were acquired under identical signal intensity settings. Grey-level images (a, c, e, g) were subjected to an 8-bit color look-up table (b, d, f, h), respectively, for visual comparison to represent differences in mineralization density between samples; see color code inset (b), wherein cool colors denote a lower mineralization density and hot colors represent higher mineralization densities. For each figure, the dentine is at the bottom of the image.

The data presented (fig. 2) also suggests that a hypoplastic enamel phenotype results in the CFTR-null, but not the CFTR-ΔF508, pigs. While a larger sample size would be needed to confirm this, a possible explanation would be that some, although significantly compromised, CTFR activity is still apparent in these CFTR-ΔF508 pigs, while a total ablation of the CFTR protein was achieved in the CFTR-null pigs.

Discussion

The formation of dental enamel requires a tight control of extracellular pH and bicarbonate concentration [Sasaki et al., 1991; Smith, 1998; Lacruz et al., 2010a]. Crystal growth and proteinase activity in the enamel extracellular space are thought to be pH-dependent phenomena requiring dynamic cellular transport processes that constantly adjust their activity to maintain the extracellular pH at a near physiologic level [Smith, 1998; Takagi et al., 1998]. There is now growing evidence that gene regulation and protein expression of many ion transporters are required to maintain an enamel pH that permits normal enamel mineralization [Lyaruu et al., 2008; Lacruz et al., 2010a]. These ion transporters include the bicarbonate transporters and chloride channels [Lacruz et al., 2010a]. In enamel organ cells, the particular cellular location of each ion transporter examined is not yet fully appreciated [Josephsen et al., 2010], but based on our own immunolocalization data for AE2 [Paine et al., 2008], and data for Cftr [Bronckers et al., 2010], our working model has both AE2 and Cftr located at the apical membrane of polarized ameloblast cells thus providing a mechanism for ameloblast-directed traffic of HCO3– and Cl– between ameloblast cells and the enamel extracellular matrix [Lacruz et al., 2010a].

In this study, we used cells derived from rat enamel organ epithelium to examine the gene expression profiles of 2 enamel-specific control proteins, i.e. Enam and Odam, and the ion transporters AE2 and Cftr. The gene expression profiles of Enam and Odam were as predicted based on previously published data [Hu et al., 2000; Moffatt et al., 2008], indicating that our RNA samples were appropriate to study other gene transcripts involved with amelogenesis. Our data show that the mRNA levels of AE2 and Cftr are both upregulated during the maturation stage of amelogenesis. These data expand on previously published data using protein-specific antibodies that suggested higher AE2 [Lyaruu et al., 2008] and Cftr [Bronckers et al., 2010] protein levels during enamel maturation when compared to early stages of amelogenesis. This increase in the expression of ion transporters during enamel maturation seems intuitively correct as the intra- and extracellular movement of ions as enamel matures is more prevalent than during secretory-stage amelogenesis.

Mouse mutant models are available for both AE2 [Gawenis et al., 2004] and Cftr [Snouwaert et al., 1992], and both have clearly defined enamel anomalies [Arquitt et al., 2002; Lyaruu et al., 2008]. Here we report that a novel porcine CFTR-targeted animal model [Rogers et al., 2008; Stoltz et al., 2010] shows hypomineralized enamel and may also show abnormal enamel microstructure at birth. Pigs (Sus scrofa) have a set of primary and secondary teeth and are commonly born with erupted deciduous incisors and canines [Bivin and McClure, 1976]. This pattern of dental development allows us to investigate enamel phenotypes without confounding factors such as antibiotic use (e.g. tetracycline) or other possible systemic disturbances that may occur during postnatal life.

Conclusion

Stringent acid/base regulation during enamel biomineralization is essential for the development of healthy enamel; to achieve this, enamel epithelial cells express many pH-regulatory genes that modulate this process, and AE2 and CFTR are 2 examples. Being able to identify which of these proteins respond to a changing environment during amelogenesis will help to better define the complex acid/base transport processes involved in enamel biomineralization.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Charles E. Smith (McGill University, Canada) and Malcolm L. Snead (University of Southern California, USA) for valuable discussions on this topic and their support of this project. This work was supported by grants DE013404, DE019629, HL051670, and HL091842 from the National Institutes of Health and from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Glossary

Abbreviations used in this paper

| Actb | β-Actin |

| AE2 | anion exchanger 2 |

| BSE | backscattered electron microscopy |

| CF | cystic fibrosis |

| CFTR | cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

References

- Arquitt C.K., Boyd C., Wright J.T. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene (CFTR) is associated with abnormal enamel formation. J Dent Res. 2002;81:492–496. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atar M., Korperich E.J. Systemic disorders and their influence on the development of dental hard tissues: a literature review. J Dent. 2010;38:296–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo T.D., Feijo G.C., Bezerra A.C. Presence of developmental defects of enamel in cystic fibrosis patients. J Dent Child (Chic) 2006;73:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banales J.M., Masyuk T.V., Bogert P.S., Huang B.Q., Gradilone S.A., Lee S.O., Stroope A.J., Masyuk A.I., Medina J.F., LaRusso N.F. Hepatic cystogenesis is associated with abnormal expression and location of ion transporters and water channels in an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1637–1646. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivin W.S., McClure R.C. Deciduous tooth chronology in the mandible of the domestic pig. J Dent Res. 1976;55:591–597. doi: 10.1177/00220345760550040701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronckers A., Kalogeraki L., Jorna H.J., Wilke M., Bervoets T.J., Lyaruu D.M., Zandieh-Doulabi B., Denbesten P., de Jonge H. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is expressed in maturation stage ameloblasts, odontoblasts and bone cells. Bone. 2010;46:1188–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawenis L.R., Ledoussal C., Judd L.M., Prasad V., Alper S.L., Stuart-Tilley A., Woo A.L., Grisham C., Sanford L.P., Doetschman T., Miller M.L., Shull G.E. Mice with a targeted disruption of the AE2 Cl-/HCO3-exchanger are achlorhydric. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30531–30539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403779200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.C., Zhang C., Sun X., Yang Y., Cao X., Ryu O., Simmer J.P. Characterization of the mouse and human PRSS17 genes, their relationship to other serine proteases, and the expression of PRSS17 in developing mouse incisors. Gene. 2000;251:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephsen K., Takano Y., Frische S., Praetorius J., Nielsen S., Aoba T., Fejerskov O. Ion transporters in secretory and cyclically modulating ameloblasts: a new hypothesis for cellular control of preeruptive enamel maturation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1299–C1307. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00218.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz R.S., Nanci A., Kurtz I., Wright J.T., Paine M.L. Regulation of pH during amelogenesis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2010a;86:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacruz R.S., Nanci A., White S.N., Wen X., Wang H., Zalzal S.F., Luong V.Q., Schuetter V.L., Conti P.S., Kurtz I., Paine M.L. The sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (NBCe1) is essential for normal development of mouse dentition. J Biol Chem. 2010b;285:24432–24438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyaruu D.M., Bronckers A.L., Mulder L., Mardones P., Medina J.F., Kellokumpu S., Oude Elferink R.P., Everts V. The anion exchanger Ae2 is required for enamel maturation in mouse teeth. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt P., Smith C.E., St-Arnaud R., Nanci A. Characterization of Apin, a secreted protein highly expressed in tooth-associated epithelia. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:941–956. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narang A., Maguire A., Nunn J.H., Bush A. Oral health and related factors in cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:702–707. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.8.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine M.L., Snead M.L., Wang H.J., Abuladze N., Pushkin A., Liu W., Kao L.Y., Wall S.M., Kim Y.H., Kurtz I. Role of NBCe1 and AE2 in secretory ameloblasts. J Dent Res. 2008;87:391–395. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C.S., Stoltz D.A., Meyerholz D.K., Ostedgaard L.S., Rokhlina T., Taft P.J., Rogan M.P., Pezzulo A.A., Karp P.H., Itani O.A., Kabel A.C., Wohlford-Lenane C.L., Davis G.J., Hanfland R.A., Smith T.L., Samuel M., Wax D., Murphy C.N., Rieke A., Whitworth K., Uc A., Starner T.D., Brogden K.A., Shilyansky J., McCra P.B., Jr., Zabner J., Prather R.S., Welsh M.J. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science. 2008;321:1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.1163600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S., Takagi T., Suzuki M. Cyclical changes in pH in bovine developing enamel as sequential bands. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(91)90090-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker H., Amlal H., Frizzell R., Ulrich C.D., 2nd, Soleimani M. CFTR drives Na+-nHCO-3 cotransport in pancreatic duct cells: a basis for defective HCO-3 secretion in CF. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C16–C25. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.E. Cellular and chemical events during enamel maturation. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:128–161. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.E., Nanci A. A method for sampling the stages of amelogenesis on mandibular rat incisors using the molars as a reference for dissection. Anat Rec. 1989;225:257–266. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092250312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.E., Nanci A., Moffatt P. Evidence by signal peptide trap technology for the expression of carbonic anhydrase 6 in rat incisor enamel organs. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114(suppl 1):147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00273.x. discussion 164–145, 380–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snouwaert J.N., Brigman K.K., Latour A.M., Malouf N.N., Boucher R.C., Smithies O., Koller B.H. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science. 1992;257:1083–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz D.A., Meyerholz D.K., Pezzulo A.A., Ramachandran S., Rogan M.P., Davis G.J., Hanfland R.A., Wohlford-Lenane C., Dohrn C.L., Bartlett J.A., Nelson 4th G.A., Chang E.H., Taft P.J., Ludwig P.S., Estin M., Hornick E.E., Launspach J.L., Samuel M., Rokhlina T., Karp P.H., Ostedgaard L.S., Uc A., Starner T.D., Horswill A.R., Brogden K.A., Prather R.S., Richter S.S., Shilyansky J., McCray P.B., Jr., Zabner J., Welsh M.J. Cystic fibrosis pigs develop lung disease and exhibit defective bacterial eradication at birth. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:29ra31. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui W., Boyd C., Wright J.T. Altered pH regulation during enamel development in the cystic fibrosis mouse incisor. J Dent Res. 2003;82:388–392. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi T., Ogasawara T., Tagami J., Akao M., Kuboki Y., Nagai N., LeGeros R.Z. pH and carbonate levels in developing enamel. Connect Tissue Res. 1998;38:181–187. doi: 10.3109/03008209809017035. discussion 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J.T., Kiefer C.L., Hall K.I., Grubb B.R. Abnormal enamel development in a cystic fibrosis transgenic mouse model. J Dent Res. 1996;75:966–973. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750041101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]