Abstract

OBJECTIVE

In mice, 4F, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide that restores HDL function, prevents diabetes-induced atherosclerosis. We sought to determine whether HDL function is impaired in type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients and whether 4F treatment improves HDL function in T2D patient plasma in vitro.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

HDL anti-inflammatory function was determined in 93 T2D patients and 31 control subjects as the ability of test HDLs to inhibit LDL-induced monocyte chemotactic activity in human aortic endothelial cell monolayers. The HDL antioxidant properties were measured using a cell-free assay that uses dichlorofluorescein diacetate. Oxidized fatty acids in HDLs were measured by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. In subgroups of patients and control subjects, the HDL inflammatory index was repeated after incubation with L-4F.

RESULTS

The HDL inflammatory index was 1.42 ± 0.29 in T2D patients and 0.70 ± 0.19 in control subjects (P < 0.001). The cell-free assay was impaired in T2D patients compared with control subjects (2.03 ± 1.35 vs. 1.60 ± 0.80, P < 0.05), and also HDL intrinsic oxidation (cell-free assay without LDL) was higher in T2D patients (1,708 ± 739 vs. 1,233 ± 601 relative fluorescence units, P < 0.001). All measured oxidized fatty acids were significantly higher in the HDLs of T2D patients. There was a significant correlation between the cell-free assay values and the content of oxidized fatty acids in HDL fractions. L-4F treatment restored the HDL inflammatory index in diabetic plasma samples (from 1.26 ± 0.17 to 0.71 ± 0.11, P < 0.001) and marginally affected it in healthy subjects (from 0.81 ± 0.16 to 0.66 ± 0.10, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with T2D, the content of oxidized fatty acids is increased and the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of HDLs are impaired.

Type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients remain at higher risk of vascular events compared with nondiabetic subjects, despite achieving recommended targets of serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and glycemia; therefore, other factors must be involved in this risk inherent in the diabetic condition (1). Recent evidence suggests that circulating lipoproteins might significantly differ in their biological activities in relation to vascular function (2–4). We hypothesized that qualitative, in addition to quantitative, differences in lipoproteins might be one of the factors responsible for the “unexplained” residual risk in diabetic patients, especially because lipoproteins are associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, which are considered to be important steps in atherosclerosis development.

VLDL and LDL particles isolated from patients with T2D or metabolic syndrome have an increased susceptibility to lipolysis, and this results in a higher concentration of nonesterified fatty acids and increased content of lysophosphatidylcholine in lipoproteins (5); both of these bioactive lipids may contribute to the proinflammatory state in these individuals. Oxidized LDL induces the release of endothelium-derived inflammatory mediators and the expression of adhesion molecules (3,6). HDL has been shown to protect LDL from oxidation (7–9), and in a coculture of human endothelial cells and human smooth muscle cells, HDL is able to inhibit the LDL-induced production of the potent monocyte chemoattractant, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, and the migration of monocytes (10). Van Lenten et al. (11) demonstrated that HDL could act as an anti-inflammatory molecule or a proinflammatory molecule, depending on the context and environment. These authors have shown that during an acute-phase response both in animals (rabbits) and in humans, HDL is converted from an anti-inflammatory to a proinflammatory (11). In subjects with T2D, increased levels of markers of chronic low-grade inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A (SAA), might be implicated in driving qualitative changes in HDLs (12). This modification in HDL composition and function would not only lower the capacity of HDLs to protect LDLs against oxidative modification but also their ability to protect the vessel from the negative effect of oxidized LDLs. We recently published that an apolipoprotein (apo) A-I mimetic peptide (D-4F) was able to bind oxidized lipids with much higher affinity than apoA-I (13), reduced atherosclerosis development, and prevented diabetes-induced oxidized lipid accumulation in a mouse model of diabetes (14).

In the present work, we demonstrate that HDL antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties are impaired in T2D patients compared with healthy control subjects. We additionally show that the apoA-I-mimetic peptide L-4F can alter the quality of HDLs in diabetic patients ex vivo.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Ninety-three patients with T2D attending the outpatient clinic of the Department of Internal Medicine (University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy) were recruited within a 12-month period. Exclusion criteria were as follows: any acute and chronic inflammatory disease, any recent (6 months) cardiovascular event, any previous diagnosis of cancer, moderate to severe chronic kidney or liver disease, and regular or frequent use of anti-inflammatory drugs or antioxidants. Thirty-one healthy control subjects (age- and sex-matched) were recruited from the relatives of the patients and from the personnel of the Department of Internal Medicine. After participants gave their written informed consent, a visit was scheduled within 7 days in fasting conditions for blood sampling (~80 mL), which was followed by a visit and an interview done by the same investigator to collect cardiovascular risk and health information.

Biochemical measurements.

Blood was collected in specific tubes for routine biochemistry (HbA1c, lipids, liver function tests, creatinine, and CRP) and in four 10-mL EDTA tubes (40 mL) that were immediately centrifuged to collect the plasma that was stored in 1-mL aliquots at −80C° for the subsequent analysis. All the assays were performed in a double-blinded manner.

SAA.

SAA levels were determined using a Human SAA ELISA kit (no. KHA0012; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

HDL inflammatory index.

HDL ability to interfere with LDL-induced monocyte migration was measured using the monocyte chemotactic activity (MCA) assay (10). In brief, human aortic endothelial cell cultures (HAECs) were obtained from the trimmings of a donor aorta during a heart transplant according to University of California Los Angeles Institutional Board guidelines. Standard LDL (sLDL) was isolated from the plasma of normal blood donors by density-gradient ultracentrifugation, and human peripheral blood monocytes were obtained from normal healthy donors. The HAECs were grown as monolayers in culture and were treated with sLDLs (100 µg/mL LDL cholesterol) in the absence or presence of test HDLs (50 mg/mL) overnight. Solutions of LDLs or HDLs, fractionated by fast-performance liquid chromatography (FPLC), were diluted with culture medium 199 containing 10% lipoprotein-deficient serum obtained from healthy volunteers and added to culture wells. After the incubation, the supernatants were collected from the cultures, diluted 20-fold, and assayed for MCA, as described previously (15). In brief, the supernatants were added to a standard NeuroProbe chamber (NeuroProbe, Cabin John, MD), with isolated human peripheral blood monocytes added to the top. The chamber was incubated for 60 min at 37°C. After the incubation, the chamber was disassembled, and the nonmigrated monocytes were removed. The membrane was then air-dried and fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet dye. The number of migrated monocytes was determined microscopically in six standardized high-power fields counted in triplicate wells. The values obtained with test HDLs were divided by the value obtained with LDLs alone. The addition of anti-inflammatory HDLs reduces LDL-induced MCA, and this results in a value <1.0. Proinflammatory HDL conversely results in a value >1.0.

LDL inflammatory index.

For determination of the LDL inflammatory index, the test LDL was added to the cells without added HDLs, and the resulting MCA was divided by the MCA obtained after addition of sLDLs without added HDLs, as previously described (15).

Plasma inflammatory index.

For determination of the plasma index, whole plasma from patients and healthy control subjects (diluted 1:2,000 using culture medium) was incubated with HAECs, and MCA assay was performed. The index, similar to the HDL inflammatory index, was calculated normalizing the migration values obtained with the test plasma by the value of a standard reference plasma sample obtained from healthy donors.

HDL antioxidant properties were measured by 1) the cell-free assay described previously (16) as the ratio of HDL + sLDL fluorescence to sLDL alone and 2) HDL intrinsic oxidation, which is measured by performing the cell-free assay on HDLs alone (i.e., without sLDLs). HDLs used for these experiments were isolated by the dextran sulfate method. In brief, 50 mL HDL Magnetic Bead Reagent (Polymedco, Cortland Manor, NY) were mixed with 250 μL of the subject’s plasma and first incubated for 5 min at room temperature then for an additional 5 min on a magnetic particle concentrator. HDL cholesterol in the supernatant was quantified using a standard assay (Thermo DMA, San Jose, CA) (11).

The cell-free assay was performed, as described previously (16), with slight modification. In brief, 25 μL of standard LDL solution containing 2.5 μg LDL cholesterol and HDLs from each patient at two different concentrations (2.5 and 5 μg HDL cholesterol in 125 μL PBS) were incubated in a 96-well plate for 30 min at 37°C. Then, 25 μL 2’,7’-dichlorfluorescein (DCFH) solution were added to each well, and after 60 min of incubation at 37°C, fluorescence intensity was measured. Values for the fluorescence intensity induced by test HDL + sLDL were divided by the values obtained with sLDLs alone to obtain an index value. Index values ≥1.0 indicate dysfunctional HDLs (pro-oxidant HDL), while values <1.0 indicates normal, antioxidant HDLs (16).

HDL intrinsic oxidation was measured by the fluorescence intensity resulting from the interaction DCFH with HDLs alone. HDLs from each patient at two different concentrations (2.5 and 5 μg HDL cholesterol in 150 µL PBS) were incubated with 25 μL DCFH solution (0.2 mg/mL) for 60 min of incubation at 37°C. The results are expressed as relative fluorescence units (rfu).

Determination of free fatty acids in HDL-containing fractions.

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) was performed using a quadruple mass spectrometer (4000 QTRAP; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Chromatography was performed using a Luna C-18 column (3-μm particle, 150 × 3.0 mm; Phenomenex, Inc., Torrance, CA) with a security-guard cartridge (C-18; Phenomenex, Inc.) at 40°C. Detection was accomplished by using the multiple-reaction–monitoring mode with negative ion detection.

Randomly chosen sets of samples from patients and control subjects were both thawed the day of the experiment and processed under identical conditions. HDLs (50 mg cholesterol) in 1.8 mL FPLC buffer were spiked with 1.8 mL of 20 μmol/L butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in ethanol and 100 mL internal standard mixture [15(S)-HETE-d8, 12(S)-HETE-d8, 5(S)-HETE-d8, and 13(S)-HODE-d4, 10 ng/mL each] in methanol. The sample was loaded onto a preconditioned Oasis HLB solid-phase extraction cartridge (1 mL, 10 mg) on a vacuum manifold (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The solid-phase extraction cartridge was equilibrated with 1 mL methanol followed by 1 mL water before the sample load. After the sample loading, the cartridge was washed with 1 mL 5% methanol in water, and free fatty acids were subsequently eluted with 1 mL methanol. The eluate was evaporated under argon and reconstituted with 60 μL methanol, vortexed, and transferred to an autosampler vial for LC/MS/MS analysis. LC/MS/MS analysis was performed as described previously (17). The transitions monitored were mass-to-charge ratio (m/z): 319.1→179.0 for 12-HETE; 319.1→219.0 for 15-HETE; 295.0→194.8 for 13-HODE; 319.1→115.0 for 5-HETE; 295.0→171.0 for 9-HODE; 327.1→226.1 for 15(S)-HETE-d8; 327.1→184.0 for 12(S)-HETE-d8; 299.0 →197.9 for 13(S)-HODE-d4; and 327.1→115.9 for 5(S)-HETE-d8. The following chemicals were used: (±)12-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE); (±) 15-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,11Z,13E-eicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE); (±)13-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE); (±)9-hydroxy-10E,12Z-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE); (±)5-hydroxy-6E,8Z,11Z,14Z-eicosatetraenoic acid (5-HETE); 12(S)-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,10E,14Z-eicosatetraenoic-5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-d8 acid (12(S)-HETE-d8); 15(S)-hydroxy-5Z,8Z,11Z,13E-eicosatetraenoic-5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-d8 acid (15(S)-HETE-d8); 5(S)-hydroxy-6E,8Z,11Z,14Z -eicosatetraenoic-5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-d8 acid (5(S)-HETE-d8); and 13(S)-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic-9,10,12,13-d4 acid (13(S)-HODE-d4) (purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI). High-performance liquid chromatography–grade methanol was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). High-performance liquid chromatography–grade acetonitrile was obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Oasis HLB was purchased from Waters Corporation.

Ex vivo treatment with L-4F.

Ten plasma samples from patients and 10 plasma samples from healthy control subjects were randomly chosen and treated with buffer or with L-4F at 0.5 μg peptide per milliliter of plasma. For determination of the plasma inflammatory index, plasma aliquots were incubated with L-4F for 15 min at 37°C with gentle rotation and then diluted with culture medium. For determination of the HDL inflammatory index and LDL inflammatory index, plasma aliquots were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with gentle rotation and then fractionated by FPLC to obtain LDL and HDL fractions. The diluted plasma, HDLs, or LDLs then were incubated with HAEC monolayers, and the HDL inflammatory index and LDL inflammatory index were determined as described above.

Data analysis.

Data were expressed as means ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. Differences between values for patients and healthy control subjects were determined by ANOVA with JMP software (JMP version 7.0).

RESULTS

The study population characteristics are described in Table 1. Patients were obese (BMI 34 ± 8 kg/m2), 80% had a diagnosis of arterial hypertension, and 13% had a previous major cardiac event. Biochemical characteristics are shown in Table 2. Patients were in suboptimal glycemic control (HbA1c 8 ± 2%), and lipid profiles were abnormal despite 58% of them being treated with either statins or fibrates. Diabetic patients also had elevated CRP levels. Healthy volunteers had a very low cardiovascular risk, with neither diabetes nor high blood pressure, and normal lipid profile. None of the healthy volunteers were on medications or vitamin supplementations.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Patients | Control subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 93 | 31 |

| Sex (male/female) | 44/49 | 14/17 |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 11 | 58 ± 2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34 ± 8 | 24 ± 4.2* |

| High blood pressure (yes/no) | 75/18 | 0/31* |

| Previous cardiac event (yes/no) | 12/81 | 0/31* |

Data are means ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. *P < 0.05 patients vs. control subjects.

TABLE 2.

Biochemical characteristics of the study population

| Patients | Control subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 8 ± 2 | ND |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.5 | ND |

| eGFR (MDRD) | 59 ± 15 | ND |

| AST (units/L) | 25 ± 11 | 23 ± 6 |

| ALT (units/L) | 28 ± 15 | 37 ± 15 |

| GGT (units/L) | 46 ± 74 | 40 ± 17 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 182 ± 42 | 201 ± 31 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 109 ± 36 | 128 ± 30 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 46 ± 13 | 50 ± 15 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 171 ± 136 | 109 ± 50 |

| ApoA-I (mg/dL) | 135 ± 36 | 148 ± 28 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 86 ± 28 | 117 ± 13 |

| Lipoprotein (a) (mg/dL) | 39 ± 38 | ND |

| CRP (mg/L) | 9 ± 12 | 1 ± 1 |

Data are means ± SD. ND, not determined. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate using the Modification of Diet Renal Disease (MDRD) formula. AST, aspartate aminotransferase. ALT, alanine aminotransferase. GGT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

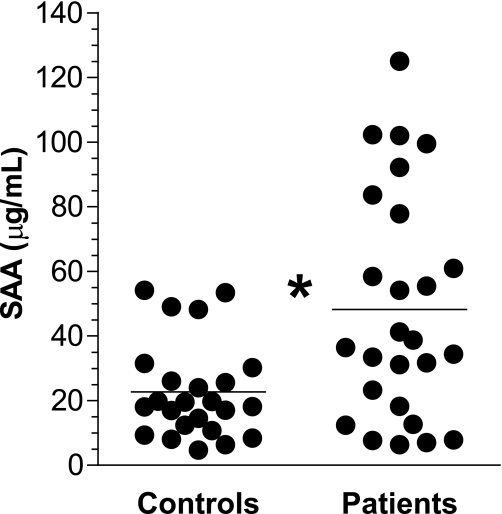

SAA.

Plasma SAA was measured in a subgroup of 26 diabetic patients and 24 healthy control subjects. SAA plasma concentrations were increased in diabetic patients compared with healthy control subjects (48.2 ± 35.1 μg/mL vs. 22.7 ± 1.5 μg/mL, P < 0.005) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Increased plasma SAA levels in diabetic patients compared with control subjects. The SAA plasma concentrations were measured (as described in research design and methods) in 26 diabetic patients and 24 healthy control subjects. *P < 0.05 patient vs. control subject.

HDL inflammatory index.

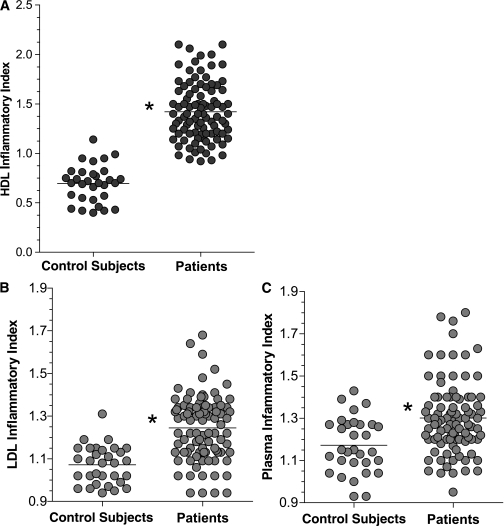

Compared with the HDLs of healthy volunteers, HDLs from diabetic patients were less able to inhibit the migration of monocytes induced by LDLs (Fig. 2A). The mean HDL inflammatory index value in patients with diabetes was significantly >1.0 (1.42 ± 0.29), indicating not only the loss of anti-inflammatory property but also an increase in proinflammatory HDLs.

FIG. 2.

The HDL inflammatory index (A), LDL inflammatory index (B), and plasma inflammatory index (C) were significantly higher in diabetic patients compared with control subjects. The HDL, LDL, and plasma inflammatory indices were determined using a monocyte chemotactic assay in the whole population of the study (93 diabetic subjects and 31 healthy control subjects) (as described in research design and methods). *P < 0.05 patients vs. control subjects.

LDL inflammatory index.

LDLs from patients with T2D induced a greater MCA compared with healthy control subjects. The LDL inflammatory index was 1.24 ± 0.15 in patients with diabetes and 1.07 ± 0.09 in control subjects (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Plasma inflammatory index.

The plasma of patients with diabetes, as a whole, exerted a proinflammatory activity (Fig. 2C); the plasma inflammatory index was not only significantly higher than in healthy volunteers (1.30 ± 0.17 vs. 1.17 ± 0.13, P < 0.001) but also was significantly >1, implying a nonneutral activity.

HDL antioxidant properties.

The HDL antioxidant properties were examined in 73 diabetic and 31 control subjects. The index obtained from the cell-free assay (as the ratio of sLDL + HDL fluorescence to sLDLs alone) was significantly higher in the diabetic patients compared with healthy volunteers, both when HDL cholesterol was added at low (2.5 μg/125 μL) and high (5.0 μg/125 μL) concentrations (2.03 ± 1.35 vs. 1.60 ± 0.80, P < 0.05, and 1.50 ± 0.99 vs. 1.11 ± 0.44, P < 0.01, respectively). Moreover, HDLs from diabetic subjects incubated with DCFH directly (without LDL) showed increased fluorescence values compared with healthy volunteers (1,708 ± 739 rfu vs. 1,233 ± 601 rfu, P < 0.001; 2.5 μg HDL cholesterol was used for this assay), indicating an increased intrinsic HDL oxidation.

Oxidized fatty acids in HDL-containing fractions.

As shown in Table 3, fatty acids resulting from oxidation of arachidonic acid (12-HETE, 15-HETE, and 5-HETE) and linoleic acid (9-HODE and 13-HODE) were significantly elevated in HDLs isolated from 11 diabetic patients compared with HDLs from 8 randomly selected control subjects. Despite the small numbers in the subset of subjects for which the content of oxidized fatty acids was determined, there was a significant correlation between the cell-free assay values and the content of oxidized fatty acids in HDL fractions (12-HETE [r2 = 0.28, P = 0.01]; 5-HETE [r2 = 0.56, P = 0.0002]; 15-HETE [r2 = 0.45, P = 0.002]; 9-HODE [r2 = 0.66, P < 0.0001]; and 13-HODE [r2 = 0.70, P < 0.0001]).

TABLE 3.

Oxidized fatty acids on HDL fractions

| Patients | Control subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 11 | 8 |

| 12-HETE (ng/50 μg HDL) | 12.9 ± 8.5 | 0.30 ± 0.17* |

| 5-HETE (ng/50 μg HDL) | 87.80 ± 20.91 | 1.38 ± 0.53* |

| 15-HETE (ng/50 μg HDL) | 4.86 ± 2.18 | 0.26 ± 0.15* |

| 9-HODE (ng/50 μg HDL) | 22.52 ± 6.32 | 1.02 ± 0.57* |

| 13-HODE (ng/50 μg HDL) | 29.56 ± 10.03 | 1.11 ± 0.68* |

Data are means ± SD. *P < 0.01 patients vs. control subjects.

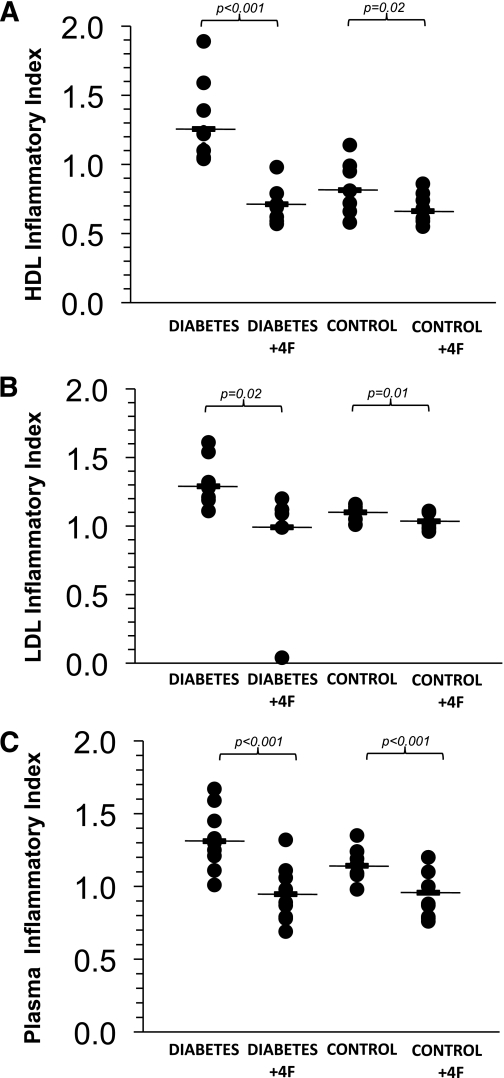

Ex vivo treatment with L-4F.

Plasma samples from 10 diabetic subjects and 10 control subjects were treated with L-4F ex vivo. Incubation with L-4F induced a significant improvement in the HDL inflammatory index in diabetic patients (buffer: 1.26 ± 0.17; L-4F: 0.71 ± 0.11; P < 0.001) and also in healthy volunteers (buffer: 0.81 ± 0.16; L-4F: 0.66 ± 0.10; P = 0.02) (Fig. 3A). In addition, L-4F treatment reduced the LDL inflammatory index in patients (buffer: 1.29 ± 0.17; L-4F: 0.99 ± 0.34; P = 0.02) and in healthy volunteers (buffer: 1.10 ± 0.04; L-4F: 1.04 ± 0.06; P = 0.01) (Fig. 3B). L-4F also was able to reduce the plasma inflammatory index in both diabetic subjects (buffer: 1.31 ± 0.20; L-4F: 0.95 ± 0.18; P = 0.0006) and control subjects (buffer: 1.14 ± 0.11; L-4F: 0.96 ± 0.16; P = 0.009) (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Ex vivo treatment with L-4F rescued HDL function and normalized the LDL inflammatory index and plasma inflammatory index in diabetic patient samples and control subjects. A: The effect of L-4F treatment on the HDL inflammatory index. B: LDL inflammatory index. C: Plasma inflammatory index. n = 10 per group (diabetic patients and healthy control subjects).

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that patients with T2D have a chronic inflammatory condition that is characterized not only by increased levels of acute-phase proteins (CRP and SAA) but also by enhanced LDL proinflammatory properties linked with the loss of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect of their HDLs. Moreover, in our data, a statistically significant correlation was found between HDL inflammatory index values and SAA plasma concentrations (r2 = 0.09, P = 0.02). It has been shown that there is a strong relationship between LDL and HDL inflammatory properties and atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits (15). In humans, the HDL inflammatory index also is significantly correlated with intima media thickening and atherosclerotic plaque size in patients with systemic lupus erythematous (18).

The cell-free assay data suggest that oxidative stress is important in mediating these changes in diabetic lipoproteins. The presence of oxidized lipids in HDLs has been proposed to be responsible for functional changes in HDLs (10). Excess generation of reactive oxygen species by hyperglycemia (19) might be involved in the enhanced production of oxidized lipids from arachidonic and linoleic acid in diabetic lipoproteins. The results in Table 3 provide some of the first evidence of increased oxidized fatty acids in human diabetic HDLs. Although the size of the subset of subjects analyzed for oxidized fatty acids was small, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between the HDL antioxidant index measured by the cell-free assay and the content of oxidized fatty acids in HDL fractions. Of interest, neither hyperglycemia nor glycated hemoglobin nor other classical risk factors were correlated with HDL dysfunction in this study (data not shown).

Results from the ex vivo treatment with L-4F are consistent with the hypothesis that oxidized lipids in HDLs and LDLs are responsible for the results reported here, because the effect of this apoA-I mimetic is related to its ability to avidly bind oxidized lipids (13).

Low-grade inflammation, as indicated by elevated plasma SAA and CRP, is likely to enhance lipid oxidation in patients with diabetes. Acute-phase proteins like SAA and the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex have been found on HDL, and their presence has been shown to favor lipid oxidation and HDL dysfunction (20). The clinical relevance of these mechanisms is indirectly supported by the recent analysis of the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) study, showing that, in T2D patients, treatment with vitamin E decreased cardiovascular death by 50% in those with the haptoglobin genotype 2-2 (20), whereas no effect was observed in haptoglobin genotype 1-1.

A limitation of this study is that we only compared diabetic patients to healthy volunteers. Thus, we cannot determine whether the lipoprotein abnormalities identified are simply markers of the disease or are causal in their clinical consequences. The number of diabetic subjects studied did not allow us to compare the HDL inflammatory index in diabetic subjects matched for arterial hypertension, BMI, or antecedent cardiovascular events. Another limitation of this study was that the antioxidant, BHT, was added after the collection of plasma and before analysis. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that there was oxidation during storage. Unterwurzacher et al. (21) added BHT to plasma and determined the content of free oxidized fatty acids in patients with diabetes per milliliter of plasma and found that the plasma content of 9-HODE and 15-HETE were elevated in diabetic plasma. Our data were determined as nanograms per 50 µg/HDL cholesterol, making direct comparisons of exact values between the two studies difficult. However, the patient and control samples in our study were treated exactly the same and analyzed on the same day so that the relative differences would be valid. Moreover, our finding that diabetic subjects had higher values is consistent with the findings of Unterwurzacher et al. (21).

HDL was isolated by FPLC in our studies, and, thus, we cannot determine how much of the oxidized fatty acids were associated with albumin, which is known to be part of the HDL proteome and which was not different in HDL from coronary heart disease (CHD) patients and control subjects in the studies of Vaisar et al. (22). Because the patient and control samples were treated identically in our studies, the differences remain significant, but the exact distribution of the oxidized fatty acids within the HDL proteome will need to be determined in future studies. In addition, these studies did not differentiate between the HDLs of different sizes. Future studies will need to determine whether HDL size correlates with the defects in HDL function described here.

Bloedon et al. (23) reported that oral doses of the 4F peptide of 4.3 and 7.14 mg/kg significantly improved the HDL inflammatory index in patients with CHD or equivalents such as diabetes compared with placebo. However, Bloedon et al. (23) did not see any significant improvement in the HDL inflammatory index of these patients compared with placebo when doses of 0.43 or 1.43 mg/kg were administered. Watson et al. (24) targeted preset plasma peptide levels and administered 0.43 mg/kg of the 4F peptide intravenously or subcutaneously. Although Watson et al. (24) achieved these preset plasma peptide levels, which greatly exceeded those achieved at the high doses administered by Bloedon et al. (23), there was no significant improvement in the HDL inflammatory index compared with placebo. Subsequently, Navab et al. (25) demonstrated that in vivo efficacy of the 4F peptide is determined by the dose administered and not by the plasma level achieved. Moreover, Navab et al. (25) found evidence that in vivo the intestine may be an important site of action for the peptide whether it is administered orally or by injection.

The HDL inflammatory index has been shown to be significantly increased (i.e., >1.0) in patients with CHD or equivalents, compared with healthy control subjects in three separate studies (23,24,26). In previous studies, we have shown that the HDL inflammatory index is inversely correlated with the ability of HDL to mediate cellular cholesterol efflux (27). Vaisar et al. (22) demonstrated that the HDL proteome is abnormal in such patients and is consistent with an inflammatory phenotype. Shao and Heinecke (28) have demonstrated that HDL oxidation by the myeloperoxidase system impairs the ability of apoA-I to mediate sterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway, and Undurti et al. (29) reported that modification of HDL by myeloperoxidase generates a proinflammatory particle. Thus, there is increasing evidence that the HDL proteome and HDL function are impaired in CHD.

In conclusion, the finding in our studies that the HDL inflammatory index in patients with diabetes is, on average, >1 indicates that, in these patients, HDL dysfunction is such that HDLs not only have lost their anti-inflammatory activity but they exert a proinflammatory activity. Whether these changes also have an impact on other functions of HDL, such as reverse cholesterol transport, endothelial function, and platelet aggregation in patients with diabetes, remains to be determined.

Because monocyte migration is only one of the many steps involved in the complex process of atherosclerosis, the effect of an intervention aimed at restoring HDL anti-inflammatory function in patients with diabetes is difficult to predict. However, because monocyte migration is one of the earliest steps in the generation of atherosclerotic lesions and because such interventions would likely also restore HDL antioxidant activity, such a therapeutic strategy, particularly if applied early in the natural course of the disease, might well be beneficial.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Public Health Service Grants HL-30568 and HL-082823; the Laubisch, Castera, and M.K. Grey Funds at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA); a network grant from Fondation Leducq; and an Internal Medicine School of Specialty Fellowship (to C.M.) from the University of Pisa.

M.N., A.M.F., and S.T.R. are principal investigators at Bruin Pharma, and A.M.F. is an officer at Bruin Pharma. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

C.M. recruited patients, researched data, contributed to the discussion, and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. A.N. researched data, contributed to the discussion, and reviewed the manuscript. B.B. recruited patients. S.I. researched data. M.N. researched data and reviewed the manuscript. A.M.F. and E.F. reviewed the manuscript. S.T.R. contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript.

Parts of this study were presented in oral form at the 71st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Diego, California, 24–28 June 2011.

The authors thank Yen Yin Lee, Department of Medicine (UCLA), for expert technical assistance and Marion Benquet, Department of Medicine (UCLA), for the help in experiments execution.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Regional patterns of disability-free life expectancy and disability-adjusted life expectancy: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1347–1352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spieker LE, Sudano I, Hürlimann D, et al. High-density lipoprotein restores endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic men. Circulation 2002;105:1399–1402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lubrano V, Baldi S, Ferrannini E, L’Abbate A, Natali A. Role of thromboxane A2 receptor on the effects of oxidized LDL on microvascular endothelium nitric oxide, endothelin-1, and IL-6 production. Microcirculation 2008;15:543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norata GD, Raselli S, Grigore L, et al. Small dense LDL and VLDL predict common carotid artery IMT and elicit an inflammatory response in peripheral blood mononuclear and endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2009;206:556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersson C, Fogelstrand L, Rosengren B, et al. Increased lipolysis by secretory phospholipase A(2) group V of lipoproteins in diabetic dyslipidaemia. J Intern Med 2008;264:155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Hinsbergh VW, Scheffer M, Havekes L, Kempen HJ. Role of endothelial cells and their products in the modification of low-density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1986;878:49–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldi S, Frascerra S, Ferrannini E, Natali A. LDL resistance to oxidation: effects of lipid phenotype, autologous HDL and alanine. Clin Chim Acta 2007;379:95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parthasarathy S, Barnett J, Fong LG. High-density lipoprotein inhibits the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1990;1044:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Functionally defective high-density lipoprotein: a new therapeutic target at the crossroads of dyslipidemia, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Rev 2006;58:342–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navab M, Imes SS, Hama SY, et al. Monocyte transmigration induced by modification of low density lipoprotein in cocultures of human aortic wall cells is due to induction of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 synthesis and is abolished by high density lipoprotein. J Clin Invest 1991;88:2039–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Lenten BJ, Hama SY, de Beer FC, et al. Anti-inflammatory HDL becomes pro-inflammatory during the acute phase response: loss of protective effect of HDL against LDL oxidation in aortic wall cell cocultures. J Clin Invest 1995;96:2758–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chait A, Han CY, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis: lipoprotein-associated inflammatory proteins: markers or mediators of cardiovascular disease? J Lipid Res 2005;46:389–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Jung CL, et al. Anti-inflammatory apoA-I-mimetic peptides bind oxidized lipids with much higher affinity than human apoA-I. J Lipid Res 2008;49:2302–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgantini C, Imaizumi S, Grijalva V, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Reddy ST. ApoA-I mimetic peptides prevent atherosclerosis development and reduce plaque inflammation in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetes 2010;59:3223–3228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Navab M, et al. Lipoprotein inflammatory properties and serum amyloid A levels but not cholesterol levels predict lesion area in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Lipid Res 2007;48:2344–2353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Navab M, Hama SY, Hough GP, Subbanagounder G, Reddy ST, Fogelman AM. A cell-free assay for detecting HDL that is dysfunctional in preventing the formation of or inactivating oxidized phospholipids. J Lipid Res 2001;42:1308–1317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imaizumi S, Grijalva V, Navab M, et al. L-4F differentially alters plasma levels of oxidized fatty acids resulting in more anti-inflammatory HDL in mice. Drug Metab Lett 2010;4:139–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMahon M, Grossman J, Skaggs B, et al. Dysfunctional proinflammatory high-density lipoproteins confer increased risk of atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2428–2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srinivasan S, Hatley ME, Bolick DT, et al. Hyperglycaemia-induced superoxide production decreases eNOS expression via AP-1 activation in aortic endothelial cells. Diabetologia 2004;47:1727–1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asleh R, Miller-Lotan R, Aviram M, et al. Haptoglobin genotype is a regulator of reverse cholesterol transport in diabetes in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res 2006;99:1419–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unterwurzacher I, Koal T, Bonn GK, Weinberger KM, Ramsay SL. Rapid sample preparation and simultaneous quantitation of prostaglandins and lipoxygenase derived fatty acid metabolites by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry from small sample volumes. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:1589–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaisar T, Pennathur S, Green PS, et al. Shotgun proteomics implicates protease inhibition and complement activation in the antiinflammatory properties of HDL. J Clin Invest 2007;117:746–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bloedon LT, Dunbar R, Duffy D, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of oral apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F in high-risk cardiovascular patients. J Lipid Res 2008;49:1344–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson CE, Weissbach N, Kjems L, et al. Treatment of patients with cardiovascular disease with L-4F, an apo-A1 mimetic, did not improve select biomarkers of HDL function. J Lipid Res 2011;52:361–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navab M, Reddy ST, Anantharamaiah GM, et al. Intestine may be a major site of action for the apoA-I mimetic peptide 4F whether administered subcutaneously or orally. J Lipid Res 2011;52:1200–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansell BJ, Navab M, Hama S, et al. Inflammatory/antiinflammatory properties of high-density lipoprotein distinguish patients from control subjects better than high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and are favorably affected by simvastatin treatment. Circulation 2003;108:2751–2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navab M, Ananthramaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. The double jeopardy of HDL. Ann Med 2005;37:173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao B, Heinecke JW. Impact of HDL oxidation by the myeloperoxidase system on sterol efflux by the ABCA1 pathway. J Proteomics 2011; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Undurti A, Huang Y, Lupica JA, Smith JD, DiDonato JA, Hazen SL. Modification of high density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase generates a pro-inflammatory particle. J Biol Chem 2009;284:30825–30835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]