Summary

Maintenance of single layered endothelium, squamous endothelial cell shape, and formation of a patent vascular lumen all require defined endothelial cell polarity. Loss of β1 integrin (Itgb1) in nascent endothelium leads to disruption of arterial endothelial cell polarity and lumen formation. The loss of polarity is manifested as cuboidal shaped endothelial cells, dysregulated levels and mis-localization of normally polarized cell-cell adhesion molecules, as well as decreased expression of the polarity gene Par3 (pard3). β1 integrin and Par3 are both localized to the endothelial layer, with preferential expression of Par3 in arterial endothelium. Luminal occlusion is also exclusively noted in arteries, and is partially rescued by replacement of Par3 protein in β1 deficient vessels. Combined, our findings demonstrate that β1 integrin functions upstream of Par3 as part of a molecular cascade required for endothelial cell polarity and lumen formation.

Keywords: β1 integrin, Itgb1, endothelium, VE-cadherin, vasculature, lumen formation, polarity, Par3, pard3, Cre, lox

Introduction

Essential to vascular morphogenesis, the molecular events that regulate endothelial lumen formation have been difficult to dissect. The information currently available has been gathered from elegant in vitro studies in 3-D culture systems that recapitulate the initial steps in the angiogenic cascade. These in vitro studies have indicated that, at least in capillary vessels, lumens result from the coalescence of vacuoles (Davis et al., 2007; Downs, 2003; Folkman and Haudenschild, 1980). A similar process has also been observed in vivo, as zebrafish intersomitic vessel sprouts demonstrate a required alignment of vacuoles from preceding cells (Kamei et al., 2006). The events are thought to be initiated downstream of integrin-extracellular matrix signaling, and require the activation of Cdc42, Rac1, pak2/4, Raf kinases, and the Par3/6/atypical PKC complex (Koh et al., 2008; Koh et al., 2009). Further confirmation of these regulatory mechanisms in vivo has been more difficult to obtain as these molecules are likely essential for multiple functions, and studies using loss- or gain-of function would require both temporal and cellular control. A more recent study has demonstrated that in the early murine aorta, a two cell cord-like structure polarizes prior to downstream activation of aPKC and Rho associated proteins to form a lumen, in lieu of vacuole accumulation (Strilic et al., 2009). Thus the mechanisms of lumen formation may be as varied and specialized as the vascular beds in which they occur.

The integrin family of heterodimeric transmembrane proteins function in cell surface binding to extracellular matrix (ECM) and simultaneous association with internal actin cytoskeletal components (Hynes, 2002). These receptors are formed by pairs of alpha (α) and beta (β) subunits, and have been associated with processes ranging from cell structure and adhesion to cell differentiation and survival (Giancotti and Ruoslahti, 1999; Hynes, 2002). Of the 22 currently recognized integrin heterodimers, at least seven (αvβ3, αvβ5, αvβ1, α1β1, α2β1, α3β1 and α5β1) are expressed by endothelial cells and have been implicated in vascular morphogenesis (Hynes and Bader, 1997; Rupp and Little, 2001; Stupack and Cheresh, 2002). However, it has been challenging to ascertain their specific contributions during blood vessel formation and homeostasis due to complex phenotypes, functional overlap, and in some cases early embryonic lethality. Because the β subunits associate with multiple α receptors, genetic inactivation of specific β subunits are fruitful, as they result in lack of expression of multiple α-β pairs.

Three recent reports using a Tie-2 Cre to ablate β1 integrin in endothelial cells showed early lethality (E9.5 - E10.5) with defects in vessel patterning typified by reduction in vascular branching from main vessels, and sac-like structures instead of uniform lumens (Carlson et al., 2008; Lei et al., 2008; Tanjore et al., 2008). As the severity of the phenotype precludes investigating roles of β1 integrin in later angiogenic events, we studied the function of β1 integrin in endothelial cells by genetic inactivation using a VE-cadherin Cre (Alva et al., 2006). The VE-cadherin Cre line initiates deletion as early as the Tie-2 Cre (E6.5), but full penetration is noted only by E14.5 (Alva et al., 2006). The slower expression kinetics results in hypomorphic phenotypes, and the possibility of investigating genetic contributions at later stages of vascular maturation. Indeed, deletion of β1 integrin using the VE-cadherin Cre results in later lethality, and has uncovered novel roles for this molecule in endothelial cell polarity and subsequent downstream events with far reaching implications for lumen formation.

Results

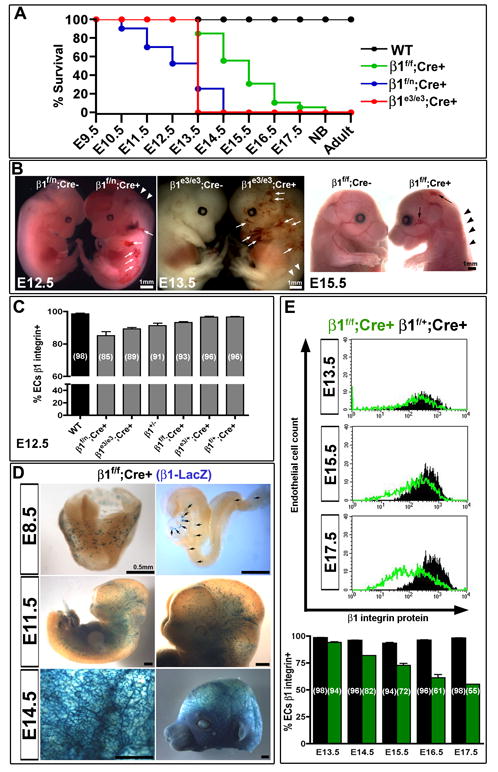

β1 integrin loss results in dose-dependent lethality

Cell-specific deletion of the Itgb1 gene (herein called β1 integrin) with homozygous floxed alleles by VE-cadherin Cre recombinase (β1f/f; Cre+) results in lethality that spans from E13.5 to E17.5 (Fig. 1A, green). When a floxed allele is replaced by a “null” allele (β1f/n; Cre+), an earlier lethality is noted ranging from E10.5 to E14.5 (Fig. 1A, blue). When inactivation of the β1 integrin gene is confined to exon 3 (β1e3/e3; Cre+), a rather sharp lethality at E13.5 is noted (Fig. 1A, red). All deletions result in embryonic death, and exhibit vascular rupture and hemorrhage (Fig. 1B). While the impact of β1 integrin ablation is similar, the timing of VE-cadherin Cre expression combined with efficiency of recombination between floxed alleles of various sizes and number, results in a gene-dosage dependent phenotype (Fig. 1C). Evaluation of β1 integrin protein expression within endothelial cell (EC) populations at E12.5 of each mouse line shows that 85% of β1f/n; Cre+ ECs express β1 integrin, as compared to 89% of β1e3/e3 (Fig. 1C, S1F).

Figure 1.

Loss of β1 integrin in the endothelium results in gene-dose dependant lethality. (A) VE-cadherin Cre deletion of β1 integrin gene in a heterozygous null background (β1f/n; Cre+, blue) results in mid-gestational lethality, as compared to late fetal lethality in homozygous floxed β1 integrin (β1f/f; Cre+, green). In contrast, VE-cadherin Cre mediated recombination of exon 3 floxed alleles leads to a sharp lethality at E13.5 (β1e3/e3; Cre+, red). (B) All deletions result in hemorrhaging (arrows) and edema (arrowheads) as evidenced in whole mount embryos. (C) Various β1 integrin deletion lines were evaluated at E12.5 for percentage of endothelial cells (ECs) that expressed β1 integrin via FACS analysis. Percentages are depicted in parenthesis. Note the mouse lines with earlier lethality have a greater reduction in β1, and the heterozygous β1 null (β1+/-) has a background level of 91%. (D) Genetic deletion of the β1f/f; Cre+ line, as demonstrated by β1 promoter driven LacZ expression, shows increasing endothelial deletion with advancing gestational age. (E) Endothelial cell β1 integrin protein expression, as measured by FACS, depicts a lag in protein loss as compared to genetic loss in D. Bottom graph depicts % of endothelial population with β1 integrin protein expression by FACS (β1f/f; Cre+ in green, β1f/+; Cre+ in black). (A-E) All graphical data shown as mean +/- SEM with a minimum of n=3 per data set, exception in (E) as data sets of n=2 do not depict error bars (E14.5 and E17.5). See also Figure S1.

Cre mediated inactivation can be traced when using the larger floxed allele (β1f) by β-galactosidase (β-gal) staining, as a LacZ reporter becomes in frame upon gene excision (Figure 1D and Fig. S1A, D). Thus, β-gal indicates both the activity of the β1 integrin promoter and the efficiency of recombination. It is clear that by E14.5 a large majority endothelial cells have at least one allele recombined (Figure 1D, Fig. S1A, D). However, evaluation of protein expression shows that β1 ablated endothelial populations comprise a small fraction of the total at E15.5. In fact, even by E17.5 only 45% of the endothelium shows complete loss of β1 integrin protein (Figure 1E, S1F). Therefore, genetic deletion may not result in protein loss for quite some time, which in this case provides a unique opportunity to evaluate β1 integrin ablation in the context of late vascular development. The multiple models of cell specific deletion also allow for assessment of the β1 integrin protein requirement in ECs. Significant lethality by E12.5 does not occur until the β1 integrin protein expression within EC populations drop below 89% (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the developing endothelium is exquisitely sensitive to β1 integrin dosage. Evaluation of β3 integrin protein expression revealed a proportional correlation between absence of β1 integrin and increase of β3, indicating a potential compensatory mechanism (Fig. S1C, F).

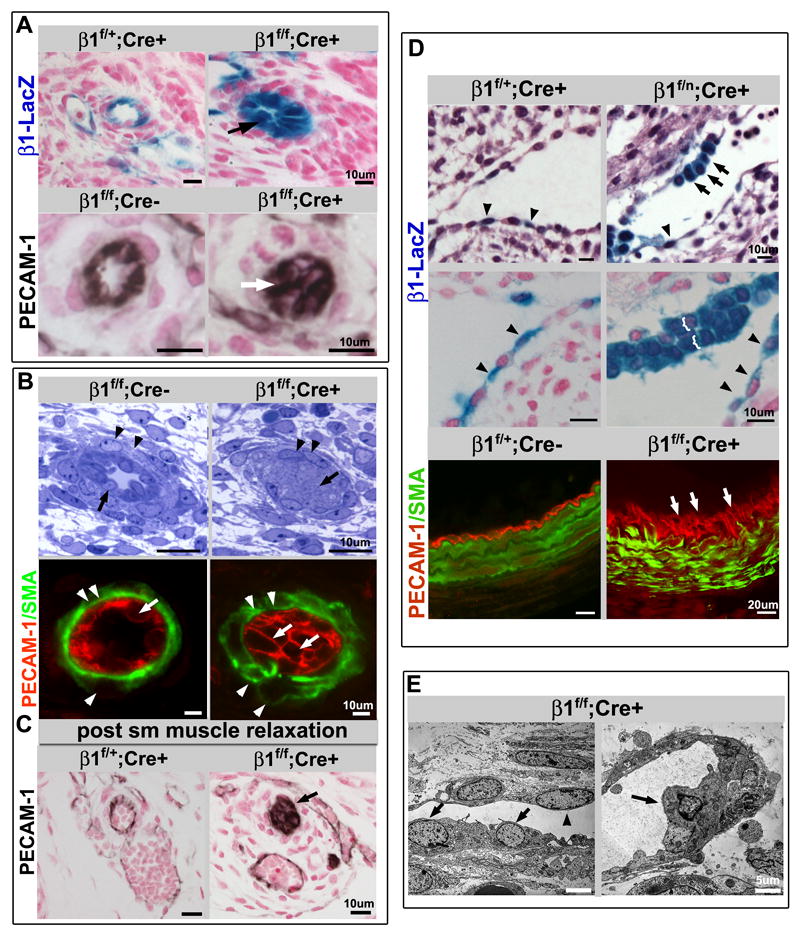

β1 integrin is critical for lumen formation

Detailed histological examination of viable endothelial specific β1f/f; Cre+ mutants revealed frequent occlusion of mid-sized vascular lumens (Fig. 2, S2A). By E14.5, the cells occluding the lumen have undergone Cre mediated β1 integrin deletion, as evidenced by LacZ expression (Fig. 2A), and strongly express the endothelial adhesion protein PECAM-1 by E15.5 (Fig. 2A-B, S2B). The observation of the phenotype in medium sized vessels and not larger arteries may be attributed to the timing of complete deletion. The aorta, other large caliber arteries, and the endocardium display multi-layered endothelium, as well as cuboidal shaped endothelial cells (Fig. 2D-E). The abnormal endothelial cell shape is also noted in mouse lines with earlier lethality β1f/n; Cre+ (Fig. 2D), and β1e3/e3; Cre+ (Fig. S1E), but at earlier time points (E12.5). The effect is exclusive to cells that have total loss of β1 integrin, as indicated by the β-gal staining in β1f/n; Cre+ embryos (Fig. 2D, arrows) and by β1 integrin immunostaining (IHC) in β1f/f; Cre+ (Fig. S3A, arrows). However the full occlusion phenotype is most prominent at later developmental stages (Fig. S3C). Luminal occlusion and cuboidal endothelial cell shape also occur after postnatal β1 integrin deletion with an inducible system (Fig. S2F). The data indicates that β1 integrin is required for maintenance of endothelial cell shape, single layered morphology, and luminal patency of mid-sized arteries after formation of the major vessels.

Figure 2.

β1 integrin endothelial deletion results in luminal occlusion, cuboidal cell shape, and stratification of the endothelial layer. (A) β-gal staining identifies β1 deleted endothelial cells (top panel) surrounding a nearly occluded lumen (arrow) in the E14.5 homozygous floxed (β1f/f; Cre+) animal. PECAM-1 (bottom, in black) also demonstrates an occluded endothelial lumen (arrow) at E15.5. Note that vessels appear occluded by endothelial cells (PECAM-1+), as also demonstrated in B (arrows). Panels are histological sections of skin with either β-gal (blue) or PECAM-1 (black), and nuclear stain in red. (B) Occlusion of the lumen was demonstrated in semithin sections of E15.5 β1f/f;Cre+ mice (arrows, top panel), and again with PECAM-1 expression (arrows, PECAM-1 in red). Endothelial deletion of β1 integrin also leads to abnormalities of smooth muscle cell (SMC) organization. While SMC morphology appears near normal in the semithin sections (arrowheads), α smooth muscle actin staining (SMA, green) depicts disorganization within SMC layers (arrowheads). (C) To ensure the occluded lumens were not a function of vascular constriction, muscle relaxants were administered to pregnant dams prior to sacrifice, and sections demonstrate no change in the occlusion phenotype (arrow). PECAM-1 in black, nuclear stain in red. (D) β1 integrin loss is associated with atypical cuboidal shape (black arrows) and stratification (brackets, and white arrows) in contrast to the normally flattened appearance of other adjacent endothelial cells (arrowheads). Top panels: E12.5 β1f/n;Cre+ endocardial cells exhibit β1-LacZ expression (β-gal staining in blue) after Cre mediated excision (counter stain in red or hemotoxylin-eosin staining in purple). β1 integrin ablated embryos also exhibit single layered squamous shaped endothelial cells (arrowheads) within the same section of cuboidal ECs or stratification, suggesting that full deletion does not occur within the entire endothelial population simultaneously. Lower panel: Stratification is also seen in E16.5 β1f/f;Cre+ (arrows) large vessel endothelium (PECAM-1 in red, SMA in green). (E) Altered cell shape at the ultrastructural level (arrows) is seen at E15.5 (β1f/f;Cre+), alongside normally shaped endothelial cells comprising the vessel wall (arrowheads). (A-E) Scale bars as labeled for each row. See also Figure S2.

To examine whether the luminal occlusion was due to cell autonomous defects in the endothelium, we evaluated smooth muscle cell morphology and function, extracellular matrix (ECM) organization, and thrombus formation. Smooth muscle cells are recruited to β1 ablated vessels, but exhibit abnormal morphology and smooth muscle actin organization (SMA) (Fig. 2B, arrowheads). Extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition was noted to be disorganized (Fig. S2C). These findings are likely due to aberrant patterning originating from the primary endothelial defect, as deletion of β1 integrin within the SMC compartment does not result in luminal occlusion (Fig. S2E). Luminal occlusion is also not a result of thrombus formation as exhibited by the presence of nucleated cells (ECs as per PECAM-1 expression) within the lumen of mutant mice (Fig. 3B, S3A-C), and lack of fibrinogen staining (Fig. S2D). To examine whether abnormal vascular smooth muscle tone could result in the observed endothelial phenotype, animals were perfused with muscle relaxants. The resultant effect was persistence of luminal occlusion and circumferential distribution of PECAM-1 (Fig. 2C).

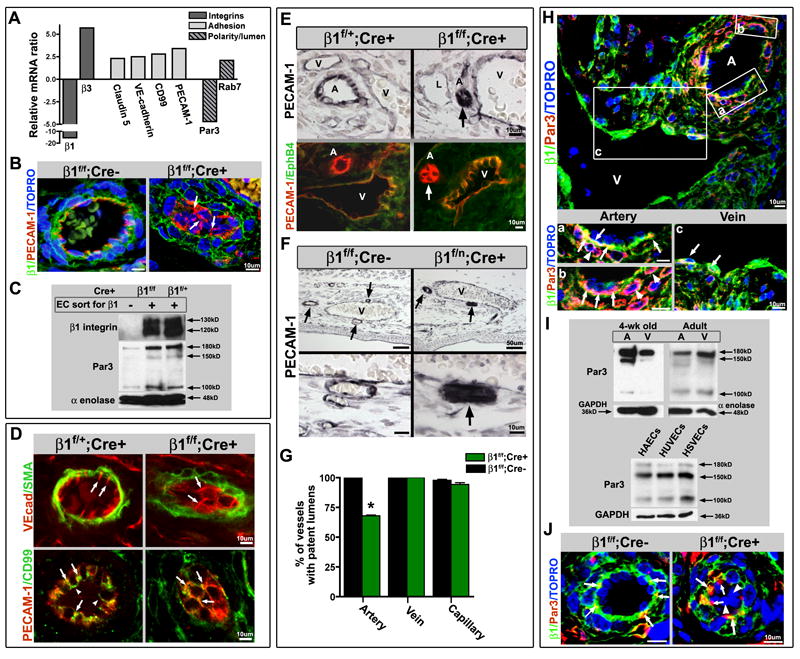

Figure 3.

Luminal occlusion and loss of polarity is an arterial phenomenon. (A) Microarray analysis of endothelial cells (ECs), sorted based on β1 integrin protein expression (from E16.5 β1f/f;Cre+ embryos), exhibited increased levels of adhesion related genes, and a decrease in the polarity gene Par3. (B) Loss of β1 integrin protein (green) results in mis-localization of PECAM-1 (red) from laterally placed cell-cell contacts to global cell surface expression (arrows). TOPRO-3 nuclear stain in blue. (C) To confirm loss of β1 integrin and Par3 on a protein level, ECs sorted in the same manner were evaluated by Western blot. Sorted β1+ and β1- endothelial cells from β1f/f;Cre+ mice, and β1+ ECs from β1f/+;Cre+ mice were loaded equally by cell number, and demonstrated loss of β1 and Par3 protein (α-enolase loading control). (D) Normally polarized expression of VE-cadherin (top panel in red, SMA in green) at lateral cell-cell contacts (arrows) is dispersed and circumferentially expressed in cells occluding the lumen within β1f/f; Cre+ vessels (arrows). CD99 (bottom panels, green) demonstrates a polarized apical expression (arrowheads), and lateral co-localization with PECAM-1 (yellow, arrows), that after β1 integrin ablation redistributes to surround the cell at E15.5 (arrows), much like PECAM-1 (in red). (E) Luminal occlusion is distinctly noted in arteries (arrows), as delineated by PECAM-1 (top panels in black, bottom panels in red) and lack of EphB4 (bottom panels, green) expression. “A” denotes arteries, “V” veins, and “L” lymphatics. (F) The extent of occlusion can vary in mid-sized arteries (arrows) at E15.5 after endothelial β1 integrin deletion, but as compared to nearby veins is a distinctly arterial phenomenon. Lower panels are high magnification of vessels in upper panels. PECAM-1 in black. (G) Vessels were evaluated at E15.5, quantified for luminal patency, and confirmed that the phenotype is exclusively arterial (n=5 each, *p< .001). (H) Par3 protein expression is preferentially expressed in embryonic arteries, as evidenced in β1f/f;Cre- at E15.5 (Par3 in red, β1 integrin in green, TOPRO-3 nuclear stain in blue). Panels (a) – (c) are higher magnification of A – V pair above. (H-a,b) Par3 co-localizes with β1 integrin (yellow) in the basal aspect of the arterial endothelial layer (arrows), but is also prominent in the surrounding smooth muscle cell layer (in red, arrowheads). (H-c) Veins also express Par3 in conjunction with β1 (yellow, arrows), but to a lesser extent than arterial vessels. (I) To evaluate Par3 expression in vessel subtypes, dorsal aortas (A) and inferior vena cavas (V) of 4 week old and adult animals were flushed with Laemmli buffer and evaluated by Western blot. Primary human endothelial cells were evaluated for Par3 expression among vessel subtypes (human aortic endothelial cells – HAECs, human umbilical vein ECs - HUVECs, and human saphenous vein ECs – HSVECs). GAPDH and α-enolase loading controls. (J) Normal basal expression of Par3 (red) with co-expression of β1 integrin (in green, co-localization in yellow) in β1f/f; Cre- vessels (arrows) is aggregated and mis-localized in β1f/f; Cre+ vessels (arrows), with complete absence in β1 deleted cells within the vessel lumen (arrowheads). TOPRO-3 nuclear stain in blue. (B, D-F, H, J) Scale bars as labeled for each row. See also Figure S3.

Loss of β1 integrin affects arterial endothelial cell polarity through Par3

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed phenotype, we performed microarray analysis and compared endothelial cells lacking β1 integrin (β1f/f; Cre+) with ECs from the same mice that still expressed β1 integrin (Figure S1G) at E16.5. A clear pattern emerged in which cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion proteins were increased, and in accordance with the FACS data, β1 integrin transcripts were decreased while β3 transcripts were increased (Fig. 3A). These findings were reproduced by qRT-PCR (Fig. S3D). β1 integrin protein loss was also confirmed in ablated vessels by IHC (Fig. 3B, S3A-C), and within the FACS sorted population by Western blotting (Fig. 3C).

An unexpected consequence of β1 integrin deletion was a reduction in transcripts coding for the polarity protein Par3 (Fig. 3A). Par3 is a well known polarity regulator that functions in a complex with aPKC and Par6 in epithelial cells (Suzuki and Ohno, 2006). Interestingly enough, other members of the complex were not transcriptionally affected by β1 integrin deletion as per our microarray and qRT-PCR analyses (Fig. S3D, legend). However, Par6 and aPKC have been shown to interact independently of Par3 (Yamanaka et al., 2003). We also confirmed that the transcriptional decrease in Par3 translated to loss of protein in β1 integrin ablated EC populations by Western blot (Fig. 3C).

Further investigation of specific cell-cell adhesion proteins in mutant mice demonstrated abnormalities in localization (Fig. 3D). VE-cadherin, which is restricted to lateral cell-cell borders of luminized vessels (Fig. 3D, arrows), was broadly redistributed in the absence of β1 integrin and present around the entire cell perimeter (Fig. 3D, arrows). Another polarized protein CD99, noted to be localized to cell junctions and have distal expression to PECAM-1 (Schenkel et al., 2002), was also mis-localized (Fig. 3D, arrowheads). In the absence of β1 integrin, CD99 was found all around the cell and was co-localized with PECAM-1 at these sites (Fig. 3D, arrows). PECAM-1 was also notably increased and relocated to circumscribe the entire cell perimeter (Figure 3B, D, arrows). Podocalyxin, an apical marker of endothelium (Meder et al., 2005), was also noted to lose its specialized luminal localization in the absence of β1 integrin (Fig. S3B). β1 integrin was predominantly found on the basal aspect of the arterial endothelial cell membrane, and absent in the β1f/f; Cre+ animal (Fig. 3B, J and Fig. S3A-C). In hybrid vessels composed of β1 positive and β1 negative ECs, the mis-localizaton of PECAM-1 was confined to β1 negative cells (Fig. S3A). The data indicates a strict regulatory relationship between cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesion molecules. In addition to luminal occlusion, stratification, and mis-orientation of polarized adhesion molecules, loss of β1 integrin also demonstrated endothelial cyst-like structures in larger vessels (Fig. S4G).

While luminal occlusion was found in medium and small sized arteries, it was not evident in veins, capillaries, or lymphatics; even though β1 integrin is expressed in all vessel types (Fig. 3E-F, S4F). When luminal patency was quantified according to vessel type, it became readily apparent that the occlusion phenotype was strictly arterial (Fig. 3G). When Par3 localization was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC), it also exhibited a preferential arterial expression (Figure 3H). Par3 was predominantly found in the basal aspect of arterial endothelial cells and there it co-localizes with β1 integrin (Fig. 3Ha-b, arrows). However, it is also expressed within the SMC layer and to some extent in veins (Fig. 3Ha-b, arrowheads, 3Hc, arrows). To verify whether there was increased Par3 expression within the arterial compartment, aortas and vena cavas from wild-type mice were flushed with laemmli buffer to enrich for endothelial protein, and evaluated for Par3 protein by Western blot (Fig. 3I). Increased expression of all Par3 isoforms was noted within the arterial compartment, but especially the 150kD isoform. These differences were only found in young (4 week old) animals (Fig. 3I). Par3 protein expression was also examined across cell lysates from primary human endothelial cell lines of arterial (HAECs), umbilical vein (HUVECs), and saphenous vein (HSVECs) origin (Fig. 3I). There were no differences between endothelial cell types in culture, but the human EC lines did demonstrate a distinct Par3 isoform pattern as compared to mouse vessels. In β1 integrin ablated vessels Par3 was no longer basally localized, but instead aggregated at cell borders (Fig. 3J, arrows). In addition, recombined cells occluding the lumen no longer expressed either β1 integrin or Par3 (Fig. 3J, arrowheads). This was noted to a larger extent in older embryos (Fig. S3C), suggesting that Par3 is mis-localized prior to its decrease in expression.

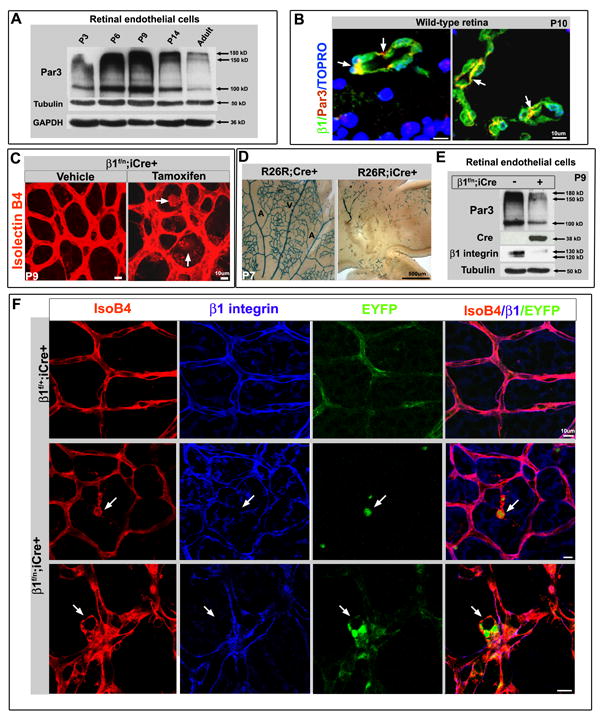

Postnatal β1 integrin ablation results in reduction of Par3 in the retinal vasculature

By using a tamoxifen inducible VE-cadherin Cre line we were able to impose Cre mediated ablation of β1 integrin in the postnatal retinal vasculature. Recombination was assessed by either β-gal staining or EYFP expression from the ROSA26 locus (R26R) Cre reporter (Soriano, 1999). Western blots for Par3 of wild-type whole retinal lysates showed an early peak between postnatal day 3 (P3) and P6 (Fig. S4A). However, as there exist multiple cell types in the retina that likely express Par3, endothelial cells were isolated and further analyzed (Fig. S4B, E). Interestingly, the retinal endothelial cells demonstrate a different developmental expression pattern for Par3, with a peak at P9, which coincides with a period of intense retinal vascular remodeling (Fig. 4A). In retinal sections, Par3 is clearly expressed in the endothelium (Fig.4B).

Figure 4.

Postnatal retinal β1 integrin deletion results in Par3 loss and abnormal endothelial cell polarity. (A) Wild-type (WT) retinal endothelial cell protein evaluated by Western blot demonstrates Par3 levels peak at P6-P9. (B) Par3 (red) is expressed in WT retinal vessels (P10) with β1 integrin (green, arrows). TOPRO-3 nuclear stain in blue. (C) Postnatal β1 integrin ablation induced by tamoxifen injection (from P2 to P7) in the β1f/n; iCre+ retina, results in large cyst-like outgrowths from the vasculature at P9 (arrows in right panel). Isolectin B4 (IsoB4) in red. (D) Postnatal tamoxifen induction when traced using a LacZ R26R Cre reporter line (R26R; iCre+) labels a small subset of retinal endothelia at P7, as compared to constitutive expression (R26R; Cre+). Arteries (A) and veins (V) labeled respectively. (E) After postnatal induction retinal endothelial cells were isolated (at P9) and evaluated by Western blot. β1 integrin protein is notably decreased in β1f/n; iCre+, as is Par3 protein levels (right column). (F) When β1f/n; iCre+ crossed to a EYFP R26R reporter undergoes β1 ablation, the β1 deleted retinal ECs (EYFP+ in green, arrows) become abnormally located in the vasculature in cyst-like structures (labeled by IsoB4 in red) and demonstrate loss of β1 protein (blue). (B-D, F) Scale bars as included for each row. See also Figure S4.

Postnatal β1 ablation resulted in discrete hemorrhagic sites in the retina (Fig. S4C), endothelial cell clumping, and cyst-like outgrowths (Fig. 4C, F, S4D); phenotypes that resemble those found in the embryo (Fig. S4G). On cross section, luminal occlusion was also observed in the retina as a result of β1 ablation (Fig. 6C, F). However, the inducible system was notably less robust when compared to the constitutive VE-cadherin Cre, as evidenced by LacZ activity from the R26R locus (Fig. 4D). Nonetheless, when Par3 protein was evaluated in β1 integrin ablated retinal endothelial cells, a decrease in Par3 protein was detected in lysates that also demonstrated Cre expression and loss of β1 integrin (Fig. 4E). To ensure that the abnormalities were due to β1 integrin loss, we further evaluated β1 IHC in conjunction with an EYFP R26R line, thus labeling cells that underwent Cre recombination. As noted in Figure 4F, cells that undergo deletion (EYFP+, green), are abnormally situated in the vasculature (isolectinB4, labeled in red), and lack β1 integrin expression (blue). Therefore, the postnatal retinal model recapitulates the findings of embryonic β1 integrin deletion in the embryo.

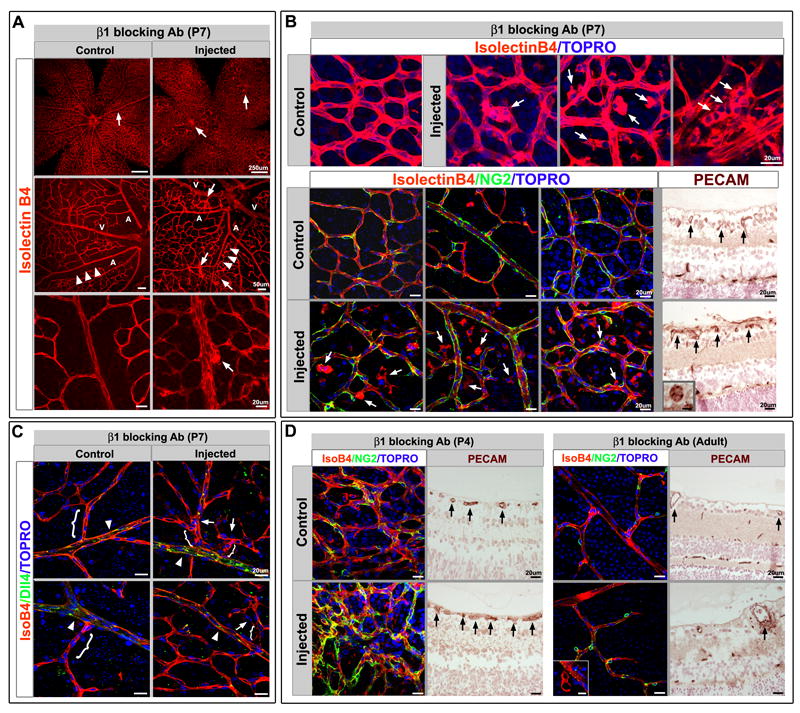

Pharmacological blockade of β1 integrin in the retina

To further confirm the role of β1 integrin in vascular morphogenesis, we induced global β1 integrin pharmacological blockade in postnatal (P4, P7 and adult) retinas, and evaluated the vasculature 72 hours later. The blockade at P7 mimics the inducible β1 integrin ablation with abnormal cell aggregation and luminal occlusion (Figure 5A, B), but also demonstrates more severe effects with excess branching (Fig. 5A). To evaluate whether pericyte coverage was affected, we investigated NG2 expression (Fig. 5B, green) and noted that while there was a lack of coverage in abnormally located ECs (Fig. 5B, arrows), the majority of vessels had NG2+ pericyte coverage equivalent to controls.

Figure 5.

β1 integrin antibody blockade recapitulates the genetic deletion phenotype. (A) β1 integrin pharmacological blockade at P7 and evaluation at P10 demonstrates increased endothelial cell (EC) aggregation and cysts (arrows) with increased branching and decreased borders between arteries (A) and veins (V). Note the normally avascular area surrounding the retinal arteries is restricted after β1 antibody blockade (arrowheads). Isolectin B4 (IsoB4) in red. (B) Top panel: The cysts are comprised of endothelial cells as demonstrated by IsoB4 and TOPRO-3 (blue) nuclear staining (arrows). Bottom panels: When retinas are evaluated for pericyte coverage (NG2, green), there is no observed effect after β1 blockade, however ECs that are abnormally positioned with respect to the vasculature, or in cysts, are not covered by pericytes (arrows). PECAM-1 staining (brown) of histological sections demonstrates abnormal vessel morphology (arrows), and luminal occlusion (inset). (C) Dll4, an arterial marker (in green) was examined to evaluate whether arterial identity was affected as a result of β1 antibody blockade. While Dll4 expression was preserved (arrowheads), increased branching with closer proximity to the main arterial vessel is apparent (arrows, brackets). (D) To evaluate the effects of β1 blockade at different ages, retinas were injected either at P4, or in the adult, and evaluated 72hrs later. Left: The P4 blockade results in abnormal vascular patterning (IsoB4 in red) with excessive pericyte coverage (NG2 in green), and luminal occlusion (PECAM-1 in brown, arrows). Right: In the adult, very few abnormalities were encountered. Rarely small cysts could be seen (IsoB4 in red, inset), as well as modest thickening of the endothelial layer (PECAM-1 in brown, arrow), while pericyte coverage was normal. TOPRO-3 nuclear stain in blue. (A-D) Scale bars as shown for each row. See also Figure S5.

We also investigated whether arterial identity was affected, as the increased branching and loss of arterial-venous (A-V) borders may suggest. Dll4, a Notch ligand known to be specific for arterial identity (Shutter et al., 2000) was evaluated. Even though the arteries exhibited increased branching and loss of the avascular zone surrounding the main arterial vessel, the expression of Dll4 was intact in arteries (Fig. 5C). To understand the requirement of β1 integrin earlier in angiogenesis, and in quiescent vessels, pharmacological β1 integrin blockade was conducted at P4, a very early stage of retinal angiogenesis, and in the adult. Earlier blockade appeared to also demonstrate branching abnormalities and EC aggregates with luminal occlusion (Fig. 5D), but there were also pericyte abnormalities in which NG2+ pericytes appeared to be increased in number (Figure 5D). As the P4 time point precedes the peak of retinal angiogenesis, it is likely the blockade also affects other populations that participate in vascular retinal patterning. In contrast, adult retinal inactivation of β1 integrin leads to very few consequential effects. Rarely, an endothelial cell would be mis-localized (Fig 5D). But for the majority of adult vessels, both morphology and pericyte coverage were undisturbed, suggesting that vascular β1 integrin may be most critical in the angiogenic stages following the primitive plexus, but prior to vessel quiescence.

As we observed an increase of β3 integrin in the absence of β1 integrin (Fig. S1C, F), the retinal model allowed us to investigate whether this upregulation had a protective or detrimental effect on vascular development. When β3 integrin blockade was induced in the postnatal retina, the retinas exhibited defects in vessel patterning with an inability to progress past the primitive plexus stage, and defects in pericyte coverage (Fig. S5). If β3 and β1 integrin were both pharmacologically blocked, the phenotype resulted in a combination of the individual phenotypes observed: EC aggregates, persistence of a primitive vascular pattern, and loss of pericyte coverage (Fig. S5).

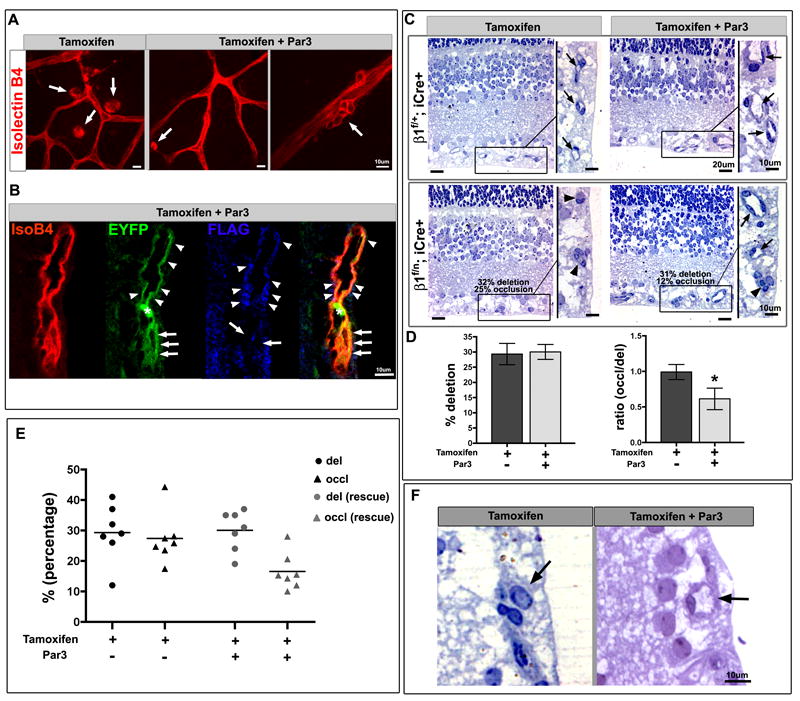

Viral-mediated Par3 delivery partially rescues luminal defects imposed by β1 integrin deletion

When retinal endothelial cells undergo β1 integrin deletion, the phenotype of luminal occlusion and cell aggregates was partially rescued by delivery of Par3 (Figure 6). Ocular lentiviral delivery of Par3 driven by a CMV promoter (Sfakianos et al., 2007) rescued the occlusion phenotype by almost 40% (p value = .025) when retinal vessels were evaluated for patency in the context of the deletion background (Fig. 6C, D). The extent of deletion was normalized after β-gal staining of endothelial cells within separate vascular beds, and was noted to be comparable between lentiviral empty vector control and Par3 rescue (Fig. 6D-E). To ensure that the normalization of vessel morphology was specifically due to viral rescue, we developed a TRI-FLAG tagged Par3 lentivirus under the control of a VE-cadherin promoter (Fig. S6), and rescued postnatal animals crossed to the EYFP R26R Cre reporter. Using this strategy, we were able to track virally rescued β1 integrin ablated ECs within the retinal vasculature (Fig 6B). Deleted ECs that were not rescued retained their abnormal shape and morphology, while rescued ECs were reverted back to a normal phenotype (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Par3 partially rescues lumen occlusion and cyst formation in endothelial β1 integrin ablation. (A-F) Postnatal animals (β1f/n; iCre+) were induced with tamoxifen (P2-P7) and retinal vasculature evaluated from P9-12. A subset was then rescued with Par3 lentiviral ocular delivery 48hrs prior to evaluation. (A) The large cysts observed with postnatal β1 integrin ablation were resolved significantly with lentiviral Par3 replacement, but a few endothelial cells (ECs) still displayed smaller atypical aggregates (arrows). Isolectin B4 (IsoB4) in red. (B) When β1f/n; iCre+ crossed to EYFP R26R (in green) retinas were rescued with FLAG-tagged Par3 lentivirus (blue), a rescued vessel demonstrates a patent lumen (arrowheads). In contrast, ECs that underwent β1 deletion (green) but were not rescued remain abnormally shaped with an occluded lumen (arrows). Asterisk denotes EYFP+ red blood cell. (C) On analysis of retinal semithin sections, β1 ablation resulted in vessel occlusion (arrowheads) that was partially rescued with Par3 protein (arrows). Boxed areas are magnified on right. (D) Retinal vessels were quantified for percentage of deletion (left) by assessing β-gal positive endothelial cells within the abdominal muscle - tamoxifen group (dark grey), tamoxifen + Par3 rescue group (light grey). The number of occluded vessels was quantified and compared to percent deletion in a ratio (right). The β1f/n; iCre+ tamoxifen group (dark grey) demonstrates that the occlusion phenotype is in direct proportion to the amount of deletion. There is a significant (*) decrease in the ratio of occluded vessels (%) to percent deletion with Par3 rescue (light grey). Data shown as mean +/- SEM, n=7 each group, p value = 0.025. (E) On a per animal basis, the percentage of deletion varies (circles), but averages at approximately 30% for both groups; while the percentage of occlusion (triangles) is dramatically reduced from 27% in the non-rescue to 16% in the rescued group. (F) Higher magnification depicting the vessel occlusion (or patency in the rescue) that was quantified in the retina (arrow). (A-C, F) Scale bars as labeled for each row. See also Figure S6.

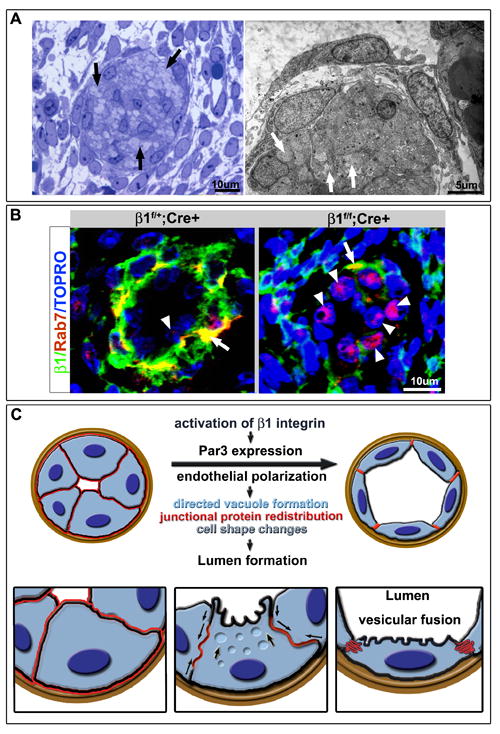

Lumen formation is halted with accumulation of intracellular vacuoles

A final aspect of the vascular occlusion phenotype is that the ECs occluding the lumen exhibited an over-accumulation of vacuoles within their cytoplasm (Figure 7A). This accumulation is not likely due to cell death as there were no observed changes in cleaved caspase-3 activity (data not shown), and the cells did not exhibit hallmarks of apoptosis by EM. However, the increase in vacuole number may be the cause or consequence of increased Rab7 transcripts found upon β1 genetic ablation (Fig. 3A). As Rab7 is noted in late stage vacuole formation (Stenmark, 2009), the data may suggest that vacuole maturation is not arrested, but vacuole fusion may be. When Rab7 protein is evaluated at late embryonic stages of β1 integrin deletion (E17.5), there is definitive increases of Rab7 in non-polarized ECs that have lost β1 integrin (Fig. 7B). As directed vacuole formation and fusion is one method of lumen formation (Iruela-Arispe and Davis, 2009), it may be that arrest of lumen formation due to β1 integrin deletion, and subsequent loss of polarity, results in abnormal vacuole accumulation. In addition, loss of β1 integrin also demonstrated endothelial cyst-like structures in larger vessels and the retina (Figs. S4G, 4C, F and 5B). The cysts may also be a result of intracellular vacuole accumulation, and possibly associated with the observed increase of Rab7 (Fig. 3A).

Figure 7.

Arrest of lumen formation and excess of cytosolic vacuoles in β1 deleted endothelial cells (ECs). (A) Semithin (left) and EM (right) analysis of luminal occlusion in E15.5 β1f/f;Cre+ animals demonstrates accumulation of multiple vesicles/vacuoles within the cell cytoplasm (arrows). (B) Evaluation of Rab7 (red) in context of β1 integrin (green) demonstrates Rab7 in the basal aspect of the endothelium and at the smooth muscle cell (SMC)/ EC junction with β1 integrin (yellow), but minimal expression within the endothelial layer (arrowhead). Upon β1 deletion, a dramatic increase of Rab7 expression in β1 ablated ECs was noted (right panel, arrowheads) with some maintenance of co-expression with β1 integrin in the SMC layer (arrow). (C) Schema depicts a working model of the cascade of events that drive lumen formation. Activation of β1 integrin instructs Par3 expression which then allows for polarization of the endothelium. Vesicular fusion to the apical cell membrane results in redistribution of junctional and adhesion proteins (in red, arrows), change in cell shape from cuboidal to squamous, and acquisition of a vascular lumen.

Discussion

Our investigation defines an overarching sequence of events that begins initially with a loss of endothelial cell polarity as a result of β1 integrin ablation. Once cell polarity is lost, the mechanisms that maintain a single endothelial layer, as well as the formation of a patent lumen, are also lost. Arrest of lumen formation can also be seen with β1 integrin pharmacological blockade, both in the avian embryo (Drake et al., 1992) and the postnatal retina (Fig. 5). Endothelial deletion of β1 integrin results in substantial increases and ubiquitous localization of cell-cell adhesion proteins: Claudin-5, PECAM-1, VE-cadherin and CD99 (Fig. 3). This resembles patterns of abnormal lumen formation in Drosophila heart tubes, where gain of function E-cadherin mutants display increased cell adhesion and subsequent loss of luminization (Santiago-Martinez et al., 2008). The data presented here suggests that at least within the endothelium, VE-cadherin, and other cell-cell adhesion molecules operate downstream of cell-matrix cues and internal cell polarity cues (Par3) to set up ordered polarized cell-cell contacts.

In models of in vitro endothelial lumen formation, events are initiated downstream of integrin-extracellular matrix signaling, but also require the activation of Cdc42, Rac1, Pak2/4 and the Par3/6/aPKC complex (Koh et al., 2008). While we did not examine Cdc42 or other Rho family GTPases, the genetic deletion of β1 integrin may affect its ability to activate Cdc42. Yet, our data also suggests a genetic link between β1 integrin and Par3, as ablation of β1 integrin results in loss of Par3. Another contrast to the in vitro data is that while lumen formation of mid-sized arteries was blocked upon β1 integrin endothelial ablation, lumens of single cell capillaries were unaffected. An initial conclusion is that much like epithelial cells (Lubarsky and Krasnow, 2003), lumen formation in vessels of distinct type and caliber is likely to employ alternative processes/molecules.

Recent data in epithelial tube formation suggests that there are Cdc42 independent mechanisms in forming a patent lumen, and that separate and distinct polarity complexes can function as polarity regulators: the association of Cdc42 with polarity complex members Par6 and aPKC being one complex and separately Par3 localized to tight junctions being another (Jaffe et al., 2008; Martin-Belmonte et al., 2007). Par6 and aPKC have been shown to interact independently of Par3 (Yamanaka et al., 2003). This divergent set of events fits nicely with our data, as we did not observe any transcriptional changes in other polarity complex members, Par6 and aPKC included (Figure S3D and data not shown). Specific to endothelium, Par3 can associate with VE-cadherin in absence of aPKC, and prior to the association of Par6 (Iden et al., 2006). Thus, it may be that cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts operate separately in maintaining cell polarity through convergent pathways, where both cadherins and integrins are capable of activating Cdc42 pathways (Desai et al., 2009; Koh et al., 2008) or alternatively regulating polarity proteins. In our study, cell-matrix cues (via β1 integrin) appear to exert initial and critical control of cell-cell adhesion protein distribution and the polarity protein Par3.

In epithelial cells, successful lumen formation requires directed centripetal vacuole movement towards the future lumen, and eventual coalescence with the plasma membrane. When β1 integrin is deleted, endothelial cells are no longer polarized, and thus may become incapable of directed vacuole movement and fusion leading to the retention of vacuoles. This is a likely cause or consequence of the increase in Rab7, a Rab GTPase that may prove critical to endothelial vacuole trafficking; analagous to other Rabs during epithelial lumen formation (Desclozeaux et al., 2008). While the downstream mechanisms of lumen formation (vacuole formation and fusion) are employed in β1 integrin ablated vessels, the phenotype is restricted to arterial endothelial cells. It is well known that sub-specification within endothelial lineages include identity markers for each endothelial subtype. Our study demonstrates that in addition to canonical arterial markers such as Dll4, Par3 (especially isoform 150kD) is preferentially expressed in nascent arterial vessels. However, the Par3 protein increase and isoform pattern in arteries is fleeting, and eventually becomes non-existent in the adult. The significance of specific Par3 isoform expression is unclear, but differences in isoform binding abilities have been previously shown (Sfakianos et al., 2007). It is likely that arteries activate a specific and exclusive set of events for lumen formation that are then silenced after successful patency.

The downstream consequence of vascular β1 integrin ablation, as dissected in this study, lends mechanistic insight into the process of polarity maintenance and lumen formation in arterial endothelium. The first and main cause of these subsequent events appears to be loss of Par3 and thus cell polarity, which includes abnormal distribution of cell-cell adhesion molecules. As a result, the endothelial cells adopt atypical cell shapes and increase their adhesive properties. While intracellular vacuoles appear capable of forming in lieu of β1 integrin, they are no longer capable of directed migration and coalescence to form a lumen. However, lumen formation is restored with the addition of Par3 protein, suggesting that the adhesion changes and lumen defects are downstream of polarity cues, which are regulated by cell-matrix interactions via β1 integrin (Figure 7C).

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Mouse lines (and their respective genotyping) VE-cadherin Cre (Alva et al., 2006), inducible VE-Cadherin Cre (Monvoisin et al., 2006), floxed β1integrin exons 2-7 (Potocnik et al., 2000), floxed β1integrin exon 3 (Raghavan et al., 2000), β1integrin null (Stephens et al., 1995), R26R LacZ (Soriano, 1999) and R26R EYFP (Srinivas et al., 2001), as described, were maintained in the Animal Research Facility at University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Care and experimental procedures performed in accordance with University guidelines. Pregnancies dated by presence of a vaginal plug (day 0.5 of gestation). For survival data, 673 embryos were evaluated for the β1f/f deletion, 104 embryos for the β1e3/e3 deletion and 234 embryos for the β1f/n deletion.

Immunohistochemistry

Littermate controls were used throughout the study. Immunostaining and β-galactosidase protocols as previously described (Alva et al., 2006; Monvoisin et al., 2006). Electron microscopy as previously described (Lee et al., 2007).

Tissue sections underwent immunostaining with the following antibodies: PECAM-1 1:100 (BD Pharmingen), Fibrinogen 1:100 (Abcam), incubation with biotinylated secondary antibodies, Vectastain ABC kit, DAB substrate and nuclear fast red counterstain (all from Vector Laboratories). Separately, tissue sections also underwent Tyramide Signal Amplification System with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) per manufacturer’s instructions with β1 integrin 1:500 (Chemicon), PECAM-1 1:500 (raised in rabbit, a generous gift from Josephine Enciso and Joseph Madri, Yale University, CT), Par3 1:300 (Upstate Biotechnology), Rab7 1:500 (Cell Signalling), and TOPRO-3 (Invitrogen) nuclear stain. Retina whole mount staining was done using Alexa Fluor conjugated- Isolectin IB4 1:100 (invitrogen) and NG2 1:100 (Chemicon) as described (Hellstrom et al., 2007), and anti-FLAG M2 1:100 (Sigma) using M.O.M. kit (Vector), with Alexa Fluor conjugated secondaries (Invitrogen).

Alternatively, for vibratome sections (250 μm) primary antibodies: PECAM-1 1:500 (BD Pharmingen); paxillin 1:100 (BD Pharmingen); laminin 1:200 (Sigma); α-smooth muscle actin FITC-labeled 1:500 (Sigma Laboratories); CD99 1:100 (from Gabriele Bixel, Max Planck Institute, Germany); Texas-Red X Phalloidin 3.5:100 (Molecular Probes); β1 integrin 1:100 (Chemicon); Claudin-5 1:100 (Zymed); EphB4 1:100 (R&D sytems); VE-cadherin 1:150 (BV 13/4, generous gift of ImClone Systems, Inc.). Primary antibodies were revealed with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with either FITC or Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). All fluorescent IHC was analyzed using a BIORAD confocal MRC1024 or a Zeiss LSM multiphoton microscope.

FACS analysis and antibodies

Embryos (or retinas) were mechanically dissociated by enzymatic digestion -collagenase (Sigma), followed by red cell lysis, and filtered (70μm and 40μm). Cells were incubated with PE-conjugated PECAM-1, FITC-conjugated β1 integrin, biotin-conjugated β3 integrin with streptavidin-Tricolor, and APC-conjugated CD45 antibodies and analyzed on a FACSCaliber with the appropriate isotype controls. Antibodies and isotype controls were purchased from BD Pharmingen; streptavidin-Tricolor from Caltag/Invitrogen.

Cell sorting and Microarray

FACSAria sorted endothelial cells from β1f/f; Cre+ whole embryos at E16.5 were gated for PECAM+/CD45- and further sorted on β1 integrin protein expression. Approximately 2-4μg of purified RNA was converted into double-stranded cDNA (Superscript, Invitrogen). 400ng of biotin-labeled cRNA was synthesized from cDNA using an IVT labeling kit (Affimetrix). Affymetrix GeneChip Fluidics Station 400 hybridized fragmented biotinylated cRNA to the Affymetrix Mouse Expression Set 430 ChipA GeneChip array, (over 14,000 full-length annotated mouse genes and nearly 4,000 ESTs). Arrays were stained and scanned using a Hewlett-Packard GeneArray Scanner. Comparisons were performed between β1f/f; Cre+ ECs that were β1+ and β1- using a total of six Affymetrix GeneChips. Data generated following probe hybridization was analyzed with Microarray Suite 5.0 (Affymetrix). Array images were visually examined for array or probe hybridization abnormalities.

Smooth muscle relaxation

Pregnant dams were anesthetized and perfused at 120mmHg with 10mg/ml adenosine (Sigma), 4mg/ml papaverine (Sigma), and 10U heparin/ml in 1X PBS to produce maximum smooth muscle relaxation. A perfusion of 2% PFA followed, the embryos removed and processed as described above.

Occlusion counts

Littermates at E15.5 were genotyped and stained with PECAM-1. Skin sections 5μm thick from embryos were evaluated 100μm apart for presence of lumen. EphB4 IHC was conducted on a subset of sequential slides to confirm venous versus arterial identity. A total of 250 arteries and veins and 620 capillaries were counted from five independent littermate pairs of β1f/f; Cre+ and β1f/f; Cre- embryos.

β integrin antibody blockade

Mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (Abott Laboratories, Inc.). For pups, eyelids were first pierced under sterile conditions with an insulin syringe (B-D), followed by intravitreal injection of 1-2μl of blocking antibody or isotype control with the aid of pulled glass micropipets and a micromanipulator; contralateral eye served as a non-injected control (3-4μl used for adults). Low endotoxin blocking antibodies for β1 and β3 integrins and isotypes (BD Pharmingen) used at 1mg/ml dilution.

Par3 lentivirus

The entire 1333nt open reading frame of mouse Par3 isoform 3 [NP_296369] (see nomenclature in supplemental materials), was fused to a triple flag tag (MADYKDHDGDYKDHDIDYKDDDDKGTSLYKKAG) to generate 3xFlag_mPar3 (plasmids fully sequenced in both orientations) and then cloned into the multiple cloning site of the lentiviral entry plasmid pRRL-sin VECADivs NLS GFP-cPPT. Replication deficient lentivirus directing expression of pRRL-sin VECADivs_3xFlag_mPar3-cPPT was then generated by the UCLA Vector core facility.

Postnatal induction of β1 integrin deletion and retina manipulations

Mice were fed or injected (intragastric) with 0.1-0.2mg (10-20μl) tamoxifen (MP Biomedicals) prepared as described (Monvoisin et al., 2006) every other day from P2-P7. Controls included Cre negative mice also fed with tamoxifen, and β1 ablated mice fed/injected with vehicle (sunflower oil). The amount of deletion was quantified by counting β-gal positive cells (nuclei of positive cells as compared to total nuclei) in the abdominal muscles of the respective mice. Purification of retinal endothelial cells was accomplished by immunobeads (see supplemental methods for full protocol).

Delivery of lentiviral proteins was accomplished by intravitreal injection of 0.5-1.0μl of 109 viral particles (see antibody blockade above), and evaluation 48hrs later. Injection of the Par3 or empty virus did not provoke any major infections or macroscopic alterations during that time period. The mice appeared to respond to light and visual cues one day after the procedure.

Western blotting

Isolated mouse tissues or cells were placed in lysis buffer, loaded onto 8% acrylamide gels, and probed with Par3 (Upstate Biotechnology), Tubulin (Sigma), GAPDH (Chemicon) Cre-recombinase (Abcam), β1 integrin (Chemicon). See supplemental methods for full protocol and antibody dilutions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Steven Smale and the members of his laboratory for use of their FACSCalibur flow cytometer, as well as the Jonsson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core and Vector Core Facilities, and the DNA microarray core at UCLA for cell sorting, lentiviral generation, and microarray. We thank Liman Zhao for assistance with animal husbandry. We also thank the contribution of the Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory Shared Resource at UCLA. This work was supported by NICHD K12-HD00850 Pediatric Scientist & CIRM Fellowships (AZ); and National Institutes of Health (CA126935 and HL085618).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alva JA, Zovein AC, Monvoisin A, Murphy T, Salazar A, Harvey NL, Carmeliet P, Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:759–767. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson TR, Hu H, Braren R, Kim YH, Wang RA. Cell-autonomous requirement for beta1 integrin in endothelial cell adhesion, migration and survival during angiogenesis in mice. Development (Cambridge, England) 2008;135:2193–2202. doi: 10.1242/dev.016378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Koh W, Stratman AN. Mechanisms controlling human endothelial lumen formation and tube assembly in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2007;81:270–285. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Gao L, Raghavan S, Liu WF, Chen CS. Cell polarity triggered by cell-cell adhesion via E-cadherin. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:905–911. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desclozeaux M, Venturato J, Wylie FG, Kay JG, Joseph SR, Le HT, Stow JL. Active Rab11 and functional recycling endosome are required for E-cadherin trafficking and lumen formation during epithelial morphogenesis. American journal of physiology. 2008;295:C545–556. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs KM. Florence Sabin and the mechanism of blood vessel lumenization during vasculogenesis. Microcirculation. 2003;10:5–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CJ, Davis LA, Little CD. Antibodies to beta 1-integrins cause alterations of aortic vasculogenesis, in vivo. Dev Dyn. 1992;193:83–91. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001930111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J, Haudenschild C. Angiogenesis in vitro. Nature. 1980;288:551–556. doi: 10.1038/288551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science (New York, NY) 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom M, Phng LK, Hofmann JJ, Wallgard E, Coultas L, Lindblom P, Alva J, Nilsson AK, Karlsson L, Gaiano N, et al. Dll4 signalling through Notch1 regulates formation of tip cells during angiogenesis. Nature. 2007;445:776–780. doi: 10.1038/nature05571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes RO, Bader BL. Targeted mutations in integrins and their ligands: their implications for vascular biology. Thrombosis and haemostasis. 1997;78:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iden S, Rehder D, August B, Suzuki A, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Wolburg H, Ohno S, Behrens J, Vestweber D, Ebnet K. A distinct PAR complex associates physically with VE-cadherin in vertebrate endothelial cells. EMBO reports. 2006;7:1239–1246. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruela-Arispe ML, Davis GE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of vascular lumen formation. Developmental cell. 2009;16:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AB, Kaji N, Durgan J, Hall A. Cdc42 controls spindle orientation to position the apical surface during epithelial morphogenesis. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;183:625–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei M, Saunders WB, Bayless KJ, Dye L, Davis GE, Weinstein BM. Endothelial tubes assemble from intracellular vacuoles in vivo. Nature. 2006;442:453–456. doi: 10.1038/nature04923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Mahan RD, Davis GE. Cdc42- and Rac1-mediated endothelial lumen formation requires Pak2, Pak4 and Par3, and PKC-dependent signaling. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:989–1001. doi: 10.1242/jcs.020693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh W, Sachidanandam K, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A, Mayo AM, Murphy EA, Cheresh DA, Davis GE. Formation of endothelial lumens requires a coordinated PKCepsilon-, Src-, Pak- and Raf-kinase-dependent signaling cascade downstream of Cdc42 activation. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:1812–1822. doi: 10.1242/jcs.045799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Chen TT, Barber CL, Jordan MC, Murdock J, Desai S, Ferrara N, Nagy A, Roos KP, Iruela-Arispe ML. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell. 2007;130:691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Liu D, Huang Y, Jovin I, Shai SY, Kyriakides T, Ross RS, Giordano FJ. Endothelial expression of beta1 integrin is required for embryonic vascular patterning and postnatal vascular remodeling. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:794–802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00443-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubarsky B, Krasnow MA. Tube morphogenesis: making and shaping biological tubes. Cell. 2003;112:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01283-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Belmonte F, Gassama A, Datta A, Yu W, Rescher U, Gerke V, Mostov K. PTEN-mediated apical segregation of phosphoinositides controls epithelial morphogenesis through Cdc42. Cell. 2007;128:383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meder D, Shevchenko A, Simons K, Fullekrug J. Gp135/podocalyxin and NHERF-2 participate in the formation of a preapical domain during polarization of MDCK cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;168:303–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monvoisin A, Alva JA, Hofmann JJ, Zovein AC, Lane TF, Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-cadherin-CreERT2 transgenic mouse: a model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3413–3422. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potocnik AJ, Brakebusch C, Fassler R. Fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells require beta1 integrin function for colonizing fetal liver, spleen, and bone marrow. Immunity. 2000;12:653–663. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan S, Bauer C, Mundschau G, Li Q, Fuchs E. Conditional ablation of beta1 integrin in skin. Severe defects in epidermal proliferation, basement membrane formation, and hair follicle invagination. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;150:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp PA, Little CD. Integrins in vascular development. Circulation research. 2001;89:566–572. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.097747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Martinez E, Soplop NH, Patel R, Kramer SG. Repulsion by Slit and Roundabout prevents Shotgun/E-cadherin-mediated cell adhesion during Drosophila heart tube lumen formation. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;182:241–248. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel AR, Mamdouh Z, Chen X, Liebman RM, Muller WA. CD99 plays a major role in the migration of monocytes through endothelial junctions. Nature immunology. 2002;3:143–150. doi: 10.1038/ni749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfakianos J, Togawa A, Maday S, Hull M, Pypaert M, Cantley L, Toomre D, Mellman I. Par3 functions in the biogenesis of the primary cilium in polarized epithelial cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;179:1133–1140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutter JR, Scully S, Fan W, Richards WG, Kitajewski J, Deblandre GA, Kintner CR, Stark KL. Dll4, a novel Notch ligand expressed in arterial endothelium. Genes & development. 2000;14:1313–1318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nature genetics. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC developmental biology. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nature reviews. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens LE, Sutherland AE, Klimanskaya IV, Andrieux A, Meneses J, Pedersen RA, Damsky CH. Deletion of beta 1 integrins in mice results in inner cell mass failure and peri-implantation lethality. Genes & development. 1995;9:1883–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strilic B, Kucera T, Eglinger J, Hughes MR, McNagny KM, Tsukita S, Dejana E, Ferrara N, Lammert E. The molecular basis of vascular lumen formation in the developing mouse aorta. Developmental cell. 2009;17:505–515. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack DG, Cheresh DA. ECM remodeling regulates angiogenesis: endothelial integrins look for new ligands. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:PE7. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, Ohno S. The PAR-aPKC system: lessons in polarity. Journal of cell science. 2006;119:979–987. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjore H, Zeisberg EM, Gerami-Naini B, Kalluri R. Beta1 integrin expression on endothelial cells is required for angiogenesis but not for vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:75–82. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka T, Horikoshi Y, Sugiyama Y, Ishiyama C, Suzuki A, Hirose T, Iwamatsu A, Shinohara A, Ohno S. Mammalian Lgl forms a protein complex with PAR-6 and aPKC independently of PAR-3 to regulate epithelial cell polarity. Curr Biol. 2003;13:734–743. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.