Abstract

Circular domains in phase separated lipid vesicles with symmetric leaflet composition commonly exhibit three stable morphologies: flat, dimpled, and budded. However, stable dimples (i.e., partially budded domains) present a puzzle since simple elastic theories of domain shape predict that only flat and spherical budded domains are mechanically stable in the absence of spontaneous curvature. We argue that this inconsistency arises from the failure of the constant surface tension ensemble to properly account for the effect of entropic bending fluctuations. Formulating membrane elasticity within an entropic tension ensemble wherein tension represents the free energy cost of extracting membrane area from thermal bending undulations of the membrane, we calculate a morphological phase diagram that contains regions of mechanical stability for each of the flat, dimpled, and budded domain morphologies.

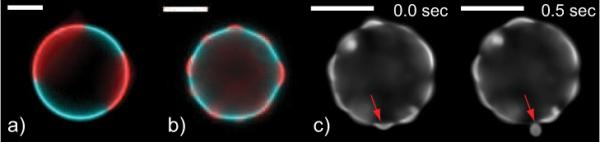

The importance of choosing an appropriate thermodynamic ensemble to account for different constraints imposed during a given experiment has been well recognized since the work of Gibbs [1]. For instance, in protein unfolding kinetics, recent single molecule studies underscore the differences between force-controlled and displacement-controlled ensembles [2]. Here we examine the effect of loading ensemble on the stability of domain morphologies in phase separated lipid membranes. In several ternary mixtures of lipids and cholesterol, two fluid phases coexist below a transition temperature [3], such that lipid domains form and can be observed with fluorescence microscopy [4–6]. These domains typically display one of three distinct morphologies with occasional transitions: flat, dimpled (partially budded), or fully budded. Equatorial views of phase separated giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) are shown in Fig. 1, as examples of the flat, dimpled, and fully budded domains that are routinely observed [7].

FIG. 1.

Domain morphologies on vesicles. (a) A phase-separated GUV showing domains (red) that are flat with respect to the vesicle (blue). (b) Dimpled domains on a GUV. (c) A dimple-to-full bud transition indicated by the red arrows. Scale bars are 10 μm. [7]

A simple elastic model accounts for the free energy differences responsible for transitions between flat and spherically budded domains [8–10]. The bending energy of the membrane competes with an interfacial free energy per unit length (line tension) at the domain phase boundary, tending to drive the domain toward curved shapes that decrease the boundary length while preserving domain area. This model predicts that above a critical size (or line tension) an initially flat domain deforms spontaneously into a completely spherical bud with an infinitesimal domain boundary, and that partially budded (dimpled) domains are mechanically stable only with non-zero spontaneous curvature. This latter prediction is inconsistent with experimental observations of dimpled domains in GUVs with no apparent spontaneous curvature [11]. Stable dimpled domains are crucial to the mechanical interactions between domains that arrest coalescence and spatially organize domains in a phase separated membrane [11].

In the absence of spontaneous curvature, we hypothesize lateral membrane tension as a plausible candidate mechanism for stabilization of dimpled domains. This surface tension is often introduced as a Lagrange multiplier conserving the total area of the (nearly incompressible) membrane [e.g., 11–13], and is determined by an interplay between membrane bending and convserved vesicle volume. Accordingly, observing that a nonspherical vesicle has an “excess” area greater than a spherical vesicle of the same volume, Yanagisawa, et al. [6] argue that domain budding could be halted once the domain deformations exhaust all excess area. For what appear optically to be spherical vesicles, this qualitative explanation does not identify the source of the extra area, nor how membrane area plays a role in the membrane energetics that govern morphology. Recent work by Semrau, et al. [13] showed that linear elastic stretching of the membrane provides a form of mathematical regularization that stabilizes dimpled domains. However, membrane stretching becomes significant only at tensions larger than ~ 10−2kBT/nm2 [14], which is roughly two orders of magnitude larger than tension estimates in experiments that observe dimpled domains [4, 7, 11, 16]. This lower tension regime is dominated by the entropy of microscopic undulations that store excess membrane area [14]. Accordingly, we refer to this as the entropic tension regime. For large GUVs, the entropic tension is often assumed to be constant [3], consistent with the idea that small deformations extract only minimal area from a large (effectively infinite) reservoir of thermal fluctuations. However, as implied by previous studies [3], and as we show explicitly here, prescribing a fixed lateral tension does not produce stable dimples, but rather only adjusts the relative stability of the flat and budded domain morphologies.

This array of clues suggests the need for some form of mathematical regularization other than constant tension to halt the budding of domains. While the linear elastic tension-area term added by Semrau, et al. [13] is mathematically sufficient, it is physically inappropriate for vesicles at low tension. Here we resolve this puzzle of the stability of partially budded domains by a more careful treatment of the effect of thermal fluctuations on tension. Specifically, in place a membrane at constant tension, we consider the more realistic choice of a finite reservoir of thermal fluctuations. Incorporating the corresponding tension-area equation of state into the free energy of the simple elastic model, we calculate the phase diagram as a function of domain size and excess (thermal) membrane area, showing that the entropic tension ensemble renders all three domain morphologies stable in parameter ranges consistent with experiments.

Our model system is an initially flat circular domain embedded in a membrane matrix of a different phase, subject to a (for now, constant) far-field tension τ. We assume the domain is much smaller than the average radius of the vesicle, such that the `background curvature' of the vesicle is negligible. The boundary of the domain experiences a line tension γ due to the unfavorable interaction at the interface of the two phases. The free energy of the domain-matrix system as it deforms is the sum of the bending energy of the membrane, the interface energy from the line tension γ, and the work done by the membrane against tension as the domain deforms [8, 9, 15], and is given by

| (1) |

where κ is the bending modulus, H is the mean curvature, is the domain and matrix membrane, r is the interface radius of the deformed domain, and rd is the initial radius of the flat domain. is the area required to deform the domain and surrounding matrix membrane from an initially flat state. For simplicity, we assume κ is the same for the two phases, and we neglect the effects of Gaussian curvature, noting however that it can become important when the Gaussian moduli of the two phases differ significantly as compared to κ [16]. Equation (1) can be written in closed analytic form by assuming that the domain deforms spherically while the matrix membrane remains flat [8, 9], which, after normalizing the deformation energy by the bending energy of a sphere, 8πκ, and the lengths by the so-called invagination length, ξ = κ/γ, takes the non-dimensional form

| (2) |

where ρd = rd/ρ and ρ = r/ξ are the normalized initial and deformed interfacial radii, and σ = τξ2/κ is the normalized membrane tension. The model predicts that stable conformations occur only for the two limits: ρ = ρd (flat) and ρ = 0 (spherical). Note that larger values of the dimensionless domain size ρd stabilize the spherical domain relative to the flat domain, while increasing the dimensionless membrane tension σ has the opposite effect.

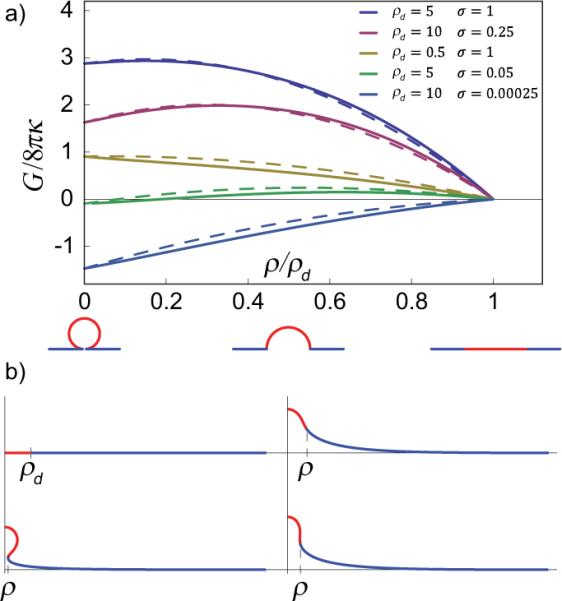

To confirm that instability of partial buds (0 < ρ/ρd < 1) is not simply an artifact of the assumptions on the deformed membrane geometry [21], we also performed numerical minimization of the shape free energy of eqn. (1) by discretizing the domain and matrix with axisymmetric finite elements [17], and holding fixed the areas of the domain and matrix using the augmented Lagrange method [18]. Figure 2(a) shows the numerical minimum free energy as a function of deformed domain radius for systems with select values of domain size ρd and membrane tension σ. Figure 2(b) shows meridional curves of the finite element model obtained by quasi-Newton numerical minimization of the free energy at several prescribed values of the deformed domain radius with σ = 0.25. For typical lipid membranes with κ = 25 kBT and ξ = 50 nm, the values of ρd and σ used in the calculations correspond to domain sizes 25 nm ≤ rd ≤ 500 nm and membrane tensions 2.5 × 10−6kBT/nm2 ≤ τ ≤ 10−2kBT/nm2, as compared to experimental values of ~ 10−5kBT/nm2 [4]. For comparison, the results of the simplified analytical model, eqn. (2), are plotted as dashed lines, demonstrating that the errors of the simplified analytical model are small, and more importantly, that the instability of the partially budded domains is not an artifact of the geometric assumptions.

FIG. 2.

Energies and shapes of deformation. (a) Normalized free energy of a budding membrane as a function of normalized domain radius ρ relative to the flat radius ρd, in the constant membrane tension ensemble, for a few values of domain size ρd and normalized surface tension σ. The solid lines are the numerical results; the dashed lines correspond to the simplified analytical model. Sketches at ρ/ρd = 0, 0.5, and 1 show corresponding analytical shapes. (b) Meridional curves from axisymmetric finite element numerical minimization of free energy for σ = 0.25. The domain is in red, and the matrix is in blue. Clockwise from upper left: equilibrium deformed configurations for .

Note that the closed analytical form of eqn. (2) clarifies the scaling of the energy sources, where the quadratic term represents the combined energy of bending and surface tension, while the linear term represents the line energy of the domain boundary. Since the quadratic term enters with a negative sign, it is clear that to find a stable dimple the energy requires additional terms with higher-order dependence on ρ, so as to produce a local energy minimum at some intermediate radius (0 < ρ/ρd < 1). The failure, in this regard, of the constant surface tension ensemble foreshadows the need to consider mechanisms that alter surface tension as a function of membrane deformation.

At finite temperature, a finite amount of excess area is stored in the thermal undulations of the membrane. This excess area can be accessed by the deforming membrane at exponentially increasing membrane tension. For a membrane with actual area , the thermal undulations are superimposed on the projected, or measurable area, , so that .

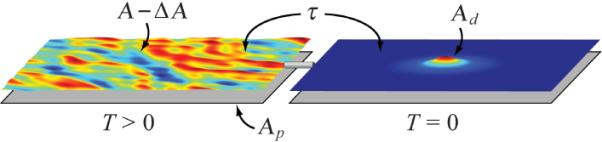

Experimentally, for vesicles near the surface area to volume ratio of a sphere, changes in vesicle volume with fixed area control , whereas changes in vesicle area with fixed volume control . To model the coupling between entropic tension and membrane deformation, imagine the domain and matrix membrane are at zero temperature and initially flat, but are coupled to a “thermal reservoir” at temperature T > 0 that has a projected area and total area , as shown in the schematic of Fig. 3. A straightforward but tedious calculation gives the entropic equation of state for the surface tension of the thermal reservoir as [19]

| (3) |

where a0 ≈ 0.7 nm2 is the area per lipid molecule for a typical lipid bilayer [20]. As the zero-temperature domain-matrix system deforms at constant projected area, it pulls in an area from the thermal reservoir. The projected area of the thermal reservoir, , remains unchanged, but its actual area decreases from to . Integrating eqn. (3), we obtain free energy of the reservoir as

| (4) |

which collapses to the constant tension ensemble for .

FIG. 3.

Schematic of the entropic tension ensemble. The thermal reservoir (left) at a finite temperature T has an actual area and a projected area , while the deformed domain-matrix system (right) is at T = 0. The small pipe represents a perfect thermal insulator that permits the flow of lipid from one region to the other, where the total amount of lipid in the ensemble is conserved, resulting in equal tension in both regions.

The contributions from membrane bending and phase boundary line tension remain unchanged from eqn. (2), and the normalized total free energy of membrane deformation in the entropic ensemble is

| (5) |

where is the system size (~the number of lipids), is the excess area fraction stored in the membrane undulations, and is the domain area fraction.

The free energy of eqn. (5) is then a function of three independent variables: the system size N, the domain area fraction α, and the relative excess membrane area ε, noting that when the reservoir is at zero tension ε achieves a maximum value proportional to ln(N). The entropic reservoir supplies the higher-order dependence on ρ necessary to overcome the bending energy's negative ρ2 dependence to yield stable dimples. Accordingly, the set of equilibrium shapes includes various combinations of flat, dimpled, and budded domains depending on location within the three-dimensional (N,α,ε) phase-space.

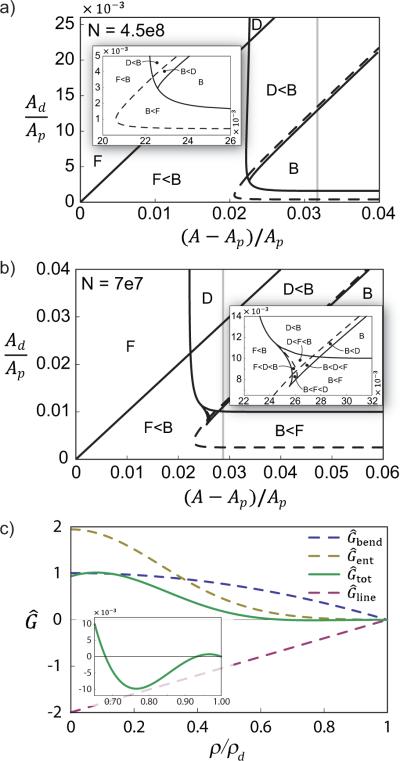

To illustrate, we plot in Fig. 4 two 2D slices through the 3D phase diagram for system sizes N = 4.5 × 108 and N = 7 × 107, corresponding to larger, , and smaller, , vesicles, respectively. Both of these 2D phase diagrams show regions where each of the flat, dimpled, and fully budded morphologies are stable. In addition, regions of metastable morphologies appear where transitions between two or even three (for N = 7 × 107) conformations may occur.

FIG. 4.

Morphological phase diagrams for (a) N = 4.5×108 and (b) N = 7×107. The letters `F', `D', and `B' represent the flat, dimpled, and fully budded domains. Regions with more than one letter indicate metastability, with the letters ordered in increasing free energy. Solid lines are “hard” phase boundaries, across which morphologies appear or disappear. Dashed lines are “preference” boundaries, indicating changes in the energetic ranking of metastable morphologies. The vertical grey lines are the excess area fraction in the reservoir at zero tension. (c) The free energy G/8πκ as a function of ρ/ρd for N = 7 × 107, , and ε = 0.026. The (lowest-energy) equilibrium state at ρ/ρd ≃ is a dimple (close-up view in inset), while flat and full buds are metastable.

Figure 4(a) shows a slice through this three parameter (N,α,ε) phase diagram containing one and two phase regions, while Fig. 4(b) contains all phases except the flat-dimple coexistence regime. As an illustration of the energy landscape in the tri-stable region of Fig. 4(b), we plot the normalized free energy along with the individual contributions from bending, line tension, and entropic surface tension in Fig. 4(c) for N = 7 × 107, α = 0.01, and ε = 0.026. In this region the dimple state is the global energy minimum, while the flat and budded morphologies are local minima. Figure 4(c) shows how the Gaussian form of offsets the negative curvature of to yield a local energy minimum at an intermediate value of ρ/ρd in . For this case, the energy barrier between the dimpled and flat states is ≈ 6.6 kBT, while the barrier between the dimpled and fully budded states is ≈ 640 kBT.

For the phase diagrams shown in Fig. 4, the range of 0.01 < ε < 0.03 translates to a range of lateral tensions 0.66 kBT/nm2 > τ > 2×10−6 kBT/nm2, with experimental values on the order of ~ 10−5 kBT/nm2 (the nominal rupture tension of a membrane is ~ 5 kBT/nm2).

The existence of stable regions for each of the morphologies over this range is consistent with the fact that all three morphologies are observed in experimental systems. It is noteworthy that both α and ε are control parameters that can be manipulated in experiments. For instance, ε can be adjusted either by micropipette aspiration [14] or by controlled thermal expansion of the membrane. On the other hand, increases in α occur passively as pairs of domains spontaneously coalesce into a single larger domain. As complete phase-separation into two simply connected domains is the thermodynamic ground state, it is expected in experiment to observe generally an “upward” flow through the phase diagrams in Fig. 4, although trajectories are not entirely vertical due to the conserved vesicle volume. As an example of a possible trajectory, one can imagine an initially small, flat domain coalescing with a flat domain, crossing the horizontal preference line in the phase diagram to yield a budded domain. That domain might coalesce with another causing traversal into the dimpled region of the phase diagram. Indeed, such sequences of coalescence that link to domain morphology have been observed experimentally [7].

We close by acknowledging that the static model of domain mechanical stability and corresponding morphological phase diagrams are an initial step toward an understanding of domain dynamics in vesicles in vitro and cell membranes in vivo. A more complete picture will require an accounting of the effects of the coupled 2D lipid hydrodynamics and 3D solvent hydrodynamics, the chemical kinetics of phase coalescence, and the potential roles of proteins in lipid organization.

References

- [1].Gibbs JW. The Collected Works of J. Williard Gibbs. Vol. 1. Yale Univ. Press; New Haven: 1957. On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schlierf M, Li H, Fernandez JM. PNAS. 2004;101:7299–7304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400033101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lipowsky R, Dimova R. J Phys Condens Matter. 2003;15:S31–S45. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baumgart T, Hess ST, Webb WW. Nature. 2003;425:821–824. doi: 10.1038/nature02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Veatch SL, Keller SL. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:268101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.268101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yanagisawa M, Imai M, Masui T, Komura S, Ohta T. Biophys J. 2007;92:115–125. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.087494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ursell TS. Bilayer elasticity in protein and lipid organization. VDM Verlag; Berlin: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lipowsky R. J. Phys II France. 1992;2:1825–1840. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lipowsky R. Biophys J. 1993;64:1133–1138. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81479-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jülicher F, Lipowsky R. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;70:2964–2967. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.70.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ursell T, Klug W, Phillips R. PNAS. 2009;106:13301–13306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903825106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jülicher F, Lipowsky R. Phys Rev E. 1996;53:2670–2683. doi: 10.1103/physreve.53.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Semrau S, Idema T, Schmidt T, Storm C. Biophys J. 2009;96:4906–4915. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Evans E, Rawicz W. Phys Rev Lett. 1990;64:2094–2097. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.64.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sens P, Turner MS. Phys Rev E. 2006;73 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.031918. 031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Baumgart T, Das S, Webb WW, Jenkins JT. Biophys J. 2005;89:1067–1080. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zienkiewicz OC, Taylor RL. The finite element method for solid and structural mechanics. 6th ed. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nocedal J, Wright SJ. Numerical optimization. Springer; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Helfrich W, Servuss RM. Nuovo Cimento. 1984;3:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Petrache HI, Dodd SW, Brown MF. Biophys J. 2000;79:3172–3192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].In particular, continuity of the membrane slope across the interface (i.e., the absence of kinks) that is observed in real systems (e.g., see [4]) was disregarded, and the bending energy of the membrane surrounding the domain was neglected.