Abstract

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has a significant genetic contribution that is incompletely characterized. To complement genome-wide association (GWA) studies, we conducted a large and systematic candidate gene study of CAD susceptibility, including analysis of many uncommon and functional variants. We examined 49,094 genetic variants in ∼2,100 genes of cardiovascular relevance, using a customised gene array in 15,596 CAD cases and 34,992 controls (11,202 cases and 30,733 controls of European descent; 4,394 cases and 4,259 controls of South Asian origin). We attempted to replicate putative novel associations in an additional 17,121 CAD cases and 40,473 controls. Potential mechanisms through which the novel variants could affect CAD risk were explored through association tests with vascular risk factors and gene expression. We confirmed associations of several previously known CAD susceptibility loci (eg, 9p21.3:p<10−33; LPA:p<10−19; 1p13.3:p<10−17) as well as three recently discovered loci (COL4A1/COL4A2, ZC3HC1, CYP17A1:p<5×10−7). However, we found essentially null results for most previously suggested CAD candidate genes. In our replication study of 24 promising common variants, we identified novel associations of variants in or near LIPA, IL5, TRIB1, and ABCG5/ABCG8, with per-allele odds ratios for CAD risk with each of the novel variants ranging from 1.06–1.09. Associations with variants at LIPA, TRIB1, and ABCG5/ABCG8 were supported by gene expression data or effects on lipid levels. Apart from the previously reported variants in LPA, none of the other ∼4,500 low frequency and functional variants showed a strong effect. Associations in South Asians did not differ appreciably from those in Europeans, except for 9p21.3 (per-allele odds ratio: 1.14 versus 1.27 respectively; P for heterogeneity = 0.003). This large-scale gene-centric analysis has identified several novel genes for CAD that relate to diverse biochemical and cellular functions and clarified the literature with regard to many previously suggested genes.

Author Summary

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has a strong genetic basis that remains poorly characterised. Using a custom-designed array, we tested the association with CAD of almost 50,000 common and low frequency variants in ∼2,000 genes of known or suspected cardiovascular relevance. We genotyped the array in 15,596 CAD cases and 34,992 controls (11,202 cases and 30,733 controls of European descent; 4,394 cases and 4,259 controls of South Asian origin) and attempted to replicate putative novel associations in an additional 17,121 CAD cases and 40,473 controls. We report the novel association of variants in or near four genes with CAD and in additional studies identify potential mechanisms by which some of these novel variants affect CAD risk. Interestingly, we found that these variants, as well as the majority of previously reported CAD variants, have similar associations in Europeans and South Asians. Contrary to prior expectations, many previously suggested candidate genes did not show evidence of any effect on CAD risk, and neither did we identify any novel low frequency alleles with strong effects amongst the genes tested. Discovery of novel genes associated with heart disease may help to further understand the aetiology of cardiovascular disease and identify new targets for therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has a substantial genetic component which is incompletely characterised. Genomewide association (GWA) studies have recently identified several novel susceptibility loci for CAD [1]–[9]. Because GWA studies involve assumption-free surveys of common genetic variation across the genome, they can identify genetic regions responsible for previously unsuspected or unknown disease mechanisms. However, despite the success of the GWA approach, it has potential limitations. Because CAD loci identified through GWA studies have predominantly been found in regions of uncertain biological relevance, further work is required to determine their precise contribution to disease aetiology. Furthermore, in contrast with their high coverage of common genetic variation, GWA studies tend to provide limited coverage of genes with well-characterised biological relevance (“candidate genes”) [2], particularly in relation to lower frequency genetic variants (such as those with minor allele frequencies of 1–5%). Such variants are also often difficult to impute from GWA data. Although candidate gene studies should provide more comprehensive coverage of lower frequency and functional variants than GWA studies, most have been inadequately powered.

To complement GWA studies, we undertook a large-scale gene-centric analysis of CAD using a customised gene array enriched with common and low frequency variants in ∼2,100 candidate cardiovascular genes reflecting a wide variety of biological pathways [10]. The array's potential to identify disease-associated lower frequency variants has been demonstrated by previous identification of strong independent associations with 2 variants in the LPA gene - rs3798220 (minor allele frequency 2%), and rs10455872 (7%) - and CAD risk [11]. We have now investigated this gene array in a further 13 studies comprising a total of 15,596 CAD cases and 34,992 controls. To enable interethnic comparisons, participants included 4,394 cases and 4,259 controls of South Asian descent, an ethnic group with high susceptibility to CAD. For further evaluation of putative novel associations, we attempted to replicate them in an additional 17,121 cases and 40,473 controls.

Results

The experimental strategy used is shown in Figure 1. In the discovery phase we genotyped participants from 12 association studies of CAD/myocardial infarction (MI), including a total of 11,202 cases and 30,733 controls of European descent (10 studies), plus 4,394 South Asian cases and 4,259 South Asian controls (2 studies) (Table 1, Table S1, with further details of the studies given in Text S1).

Figure 1. Design of the study.

Table 1. Summary details of discovery and replication stage studies.

| Stage | Study | Cases / Controls | Male (%) | Mean age (SD) of cases at diagnosis | Number of cases with MI (%) | Version of IBC array** |

| European discovery | ARIC | 424 / 8447 | 46.4 | -° | 368 (82.7) | V2 |

| BHF-FHS | 2101 / 2426 | 63.3 | 49.8 (7.7) | 1538 (73.2) | V1 | |

| BLOODOMICS - Dutch | 1462 / 1222 | 72.6 | 48.8 (12.0) | 1462 (100) | V2 | |

| BLOODOMICS - German | 1910 / 1932 | 63.3 | 59.2 (10.9) | 1181 (61.8) | V2 | |

| CARDIA | 87 / 1343 | 46.8 | -° | 86 (100) | V2 | |

| CHS | 737 / 3155 | 43.9 | -° | 381 (50.5) | V2 | |

| FOS | 59 / 6976 | 45.1 | -° | 13 (22.0) | V2 | |

| MONICA-KORA | 275 / 1413 | 57.5 | 52.9 (9.4) | >50%* | V1 | |

| PennCATH | 1027 / 489 | 66.0 | 54.2 (8.8) | 439 (40.6) | V1 | |

| PROCARDIS | 3120 / 3330 | 59.2 | 61.0 (8.7) | 2136 (68.5) | V2 | |

| Total | 11,202 / 30,733 | |||||

| South Asian discovery | PROMIS | 1856 / 1905 | 82.5 | 53.3 (10.7) | 1856 (100) | V1 |

| LOLIPOP | 2538 / 2354 | 83.7 | - | 1125 (44.4) | V2 | |

| Total | 4394 / 4259 | |||||

| Replication | CARDIoGRAM† | 15,949 / 38,823 | 57.0 | 53.5 (9.8) | 10,890 (68.3) | N/A |

| EPIC-NL | 1172 / 1650 | 30.6 | 51.9 (10.6) | 341 (30.3) | V3 | |

| Total | 17,121 / 40,473 |

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities; BHF-FHS = British Heart Foundation Family Heart Study; CARDIA = Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults; CHS = Cardiovascular Health Study; FOS = Framingham Offspring Study; LOLIPOP = London Life Sciences Prospective Population Cohort; PROCARDIS = Precocious Coronary Artery Disease; PROMIS = Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study; EPIC-NL = European Prospective Investigation into Cancer & Nutrition (Netherlands) cohort.

*All MONICA-KORA cases are either MI or sudden cardiac death.

**V2 contains an additional 132 genes (3,857 SNPs) compared to V1. SNPs on V2 were only analysed in studies that used the V2 array.

†: Details of studies in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium are presented in Table S6.

°: The 4 studies in the CARe Consortium contributed data only on prevalent CAD cases at baseline for whom ages were not available.

Associations with known CAD loci

36,799 SNPs passed QC and frequency checks and were included in the meta-analysis (reasons for exclusion of variants in each study are given in Table S2). The distribution of association P values in the discovery stage analyses are shown in Figure 2. We found significant associations with CAD for several previous GWA-identified loci contained on the array including 9p21.3 (rs1333042, combined European and South Asian P = 1.1×10−37) and 1p13.3 (rs646776, 3.1×10−17; Table S3). We also confirmed associations of other genes with strong prior evidence including the first association of a variant at the apolipoprotein E locus at genomewide significance (APOE/TOMM40, rs2075650, P = 3.2×10−8), as well as associations at apolipoprotein (a) (LPA, rs10455872, P = 1.2×10−20), and low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR, rs6511720, P = 1.1×10−8; Table S3). However, we found no persuasive evidence of association of several prominently-studied genes and variants for which the previous epidemiological evidence has been inconclusive, even though the majority of these loci were well-tagged (Table S4) and the current study was well-powered to detect associations of modest effect (Figure S1). Notable variants that did not show significant association included the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) insertion/deletion polymorphism, the cholesteryl-ester transfer protein (CETP) Taq1B polymorphism and the paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Q192R polymorphism (Table S4). Perhaps contrary to expectation, apart from the LPA variant rs3798220, we did not observe any other strong association (odds ratio >1.5) among the ∼4,500 low frequency (1–5%) variants and/or variants with suspected or known functional impact on protein structure/function or gene expression specifically selected for the inclusion on the array (Table S3).

Figure 2. Manhattan plots for discovery stage meta-analyses.

Y-axis shows unadjusted −log10(P values) from fixed-effect meta-analysis of discovery stage studies. NB: European and Combined plots are truncated at P = 10−20. Blue horizontal line at P = 10−4 indicates threshold for replication; Red horizontal line at P = 3×10−6 indicates array-wide significance level.

Novel CAD loci

Based on simulations conducted prior to the analysis (Figure S2), loci were eligible for replication if unadjusted P-values for CAD were <1×10−4 in either the primary (each ethnic group analysed separately) or secondary (combined) analyses and the loci had not been previously established with CAD. This identified 27 loci in total: 15 in the European only analysis, 3 in the South Asian only analysis, and 9 in the combined analysis (Table S5). A recent GWA meta-analysis from the CARDIoGRAM Consortium with some overlapping cohorts to those in our study, reports discovery of three of these loci [12]: COL4A1/COL4A2, ZC3HC1, CYP17A1. The P values observed for the lead variants at these loci in the current study were: COL4A1/COL4A2: rs4773144, P = 3.5×10−8; ZC3HC1: rs11556924, P = 3.1×10−7; CYP17A1: rs3824755, P = 1.2×10−7, providing further strong evidence for the association of these loci with CAD. Hence, only the lead SNPs at the 24 remaining loci were taken forward for replication. This was done in silico in 17,121 CAD cases and 40,473 controls, all of whom were of white European ancestry and derived from non-overlapping cohorts from CARDIoGRAM and EPIC-NL (Text S1, Table S6). The power of our replication sample to confirm significant associations is shown in Figure S1. Of the 24 variants taken forward, four were independently replicated (1-tailed Bonferroni-corrected P<0.05 is P<1.9×10−3; Figure 3, Table S5), comprising variants in or adjacent to: LIPA, IL5, TRIB1 and ABCG5/ABCG8 (Figure 4). For the variant at the LIPA locus, the combined P-value was 4.3×10−9, exceeding conventional thresholds for GWA studies. For each of the IL5, TRIB1 and ABCG5/ABCG8 variants, the P-value was <3×10−6, exceeding array-wide levels of significance (Figure 3). CAD associations in the individual component studies are shown in Figure S3. The CAD associations for these loci did not vary materially by age, sex or when restricted to the MI subphenotype (Figure S4).

Figure 3. Novel loci identified in the current study.

Loci ordered by chromosomal position. SNP = SNP showing strongest evidence of association in discovery stage studies; Frequency = pooled frequency of risk allele across controls; European discovery = per-allele odds ratio, confidence interval and 2-tailed P value from fixed-effect meta-analysis of European discovery stage studies; South Asian discovery = per-allele odds ratio, confidence interval and 2-tailed P value from fixed-effect meta-analysis of South Asian discovery stage studies; Combined discovery = per-allele odds ratio, confidence interval and 2-tailed P value from fixed-effect meta-analysis of all European and South Asian discovery stage studies combined; Replication = per-allele odds ratio, confidence interval and 1-tailed P value from fixed-effect meta-analysis of replication stage studies comprising non-overlapping participants from CARDIoGRAM plus all participants from EPIC-NL; Overall = P value from relevant discovery stage studies combined with the replication stage P value using Fisher's method.

Figure 4. Regional association plots for novel loci identified.

All SNPs included in meta-analysis of the European discovery stage studies are represented by diamonds, with the lead SNP (lowest P value) at each locus represented by a large red diamond. Genes are represented as horizontal arrows, with the direction of the arrow reflecting the direction of transcription. Recombination rates are represented as vertical blue peaks based on the Hapmap 2 CEU population. P values are from fixed-effect meta-analysis. LD, represented as r2, is estimated using the controls from the BHF-FHS study, or Hapmap 2 CEU population where data were not available in BHF-FHS. Vertical dashed lines represent the extent of LD with the lead SNP, based on an r2 threshold of 0.5 in the Hapmap 2 CEU population. The genes between these lines represent the most likely candidate genes for each association signal.

Potential mechanisms

To investigate whether the 4 newly identified loci associate with cardiovascular risk traits, we interrogated available data from previous GWA meta-analyses of diabetes mellitus (n = 10,128 individuals) [13], systolic blood pressure (n = 25,870) [14], and low-density (LDL) and high-density (HDL) lipoprotein-cholesterol and triglycerides (n = 99,900) [15]. This showed that the risk allele at the TRIB1 locus was associated with higher triglyceride (P = 3.2×10−53), higher LDL-C (P = 6.7×10−29) and lower HDL-C (P = 9.9×10−17) and that the ABCG5/ABCG8 risk allele was associated with higher LDL-C (P = 1.7×10−47; Figure 5). We also examined the association of the novel risk variants with gene expression in full transcriptomic profiles of circulating monocytes derived from 363 patients with premature myocardial infarction and 395 healthy blood donors from the Cardiogenics study (Text S1). We found a highly significant association (P = 1.0×10−124) of the risk allele at the LIPA locus with LIPA mRNA levels in these cells explaining ∼50% of the variance in the expression of the gene (Figure 6).There were no other highly significant associations between CAD risk alleles and gene expression at the novel loci (Table S7a and S7b).

Figure 5. Effects of novel CAD loci on known cardiovascular risk factors.

HDL-c = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-c = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Beta/odds ratio = combined effect from meta-analysis of SNP versus blood pressure/lipids/T2D. Results for lipids from meta-analysis of 46 GWA studies containing up to 99,900 individuals [15]. Results for blood pressure from the Global BPGen Consortium: a meta-analysis of 17 GWA studies containing 25,870 individuals [14]. Results for diabetes from the DIAGRAM Consortium: a meta-analysis of 3 GWA studies containing 4,549 T2DM cases and 5,579 controls [13]. * No results available due to poor quality of SNP imputation.

Figure 6. Evidence for an eQTL association in the LIPA gene.

Expression levels of LIPA in monocytes taken from 758 individuals assembled by the Cardiogenics Consortium partitioned by genotype of SNP rs2246833. Boxes indicate interquartile ranges with a white horizontal line indicating the median. Error bars represent absolute minimum and maximum levels with dots showing those levels considered to be outliers. rs2246833 is in strong linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 0.93; D′ = 1) with the CAD-associated variant at the LIPA locus (rs2246942). The T allele, which is associated with increased LIPA expression, is inherited with the G allele of rs2246942, which is associated with increased risk of coronary disease.

Ethnic-specific analyses

We explored whether associations of loci with CAD differed between individuals of white European ancestry and South Asian ancestry. For most loci, frequency of risk alleles and pattern of risk associations did not differ qualitatively by ethnicity, although the evidence of association was often weaker in South Asians, perhaps due to lower power (Figure 3, Tables S3 and S5). For the 9p21.3 locus, despite similar risk allele frequencies (Table S3), odds ratios were higher in Europeans than South Asians (rs1333042: 1.27 v 1.14; P = 0.003 for difference), though common haplotype frequencies did not vary by ethnicity (Table S8). The three variants at the TUB, LCT and MICB loci selected for replication on the basis of South Asian-specific results did not show evidence of association in Europeans (Table S5).

Discussion

Our in-depth study of ∼2,100 candidate genes has yielded several novel and potentially important findings, adding to the emerging knowledge on the genetic determination of CAD. First, we have identified several novel genes for CAD. These genes relate to diverse biochemical and cellular functions: LIPA for the locus on 10q23.3; IL5 (5q31.1); ABCG5/ABCG8 (2p21); TRIB1 (8q24.13); COL4A1/COL4A2 (13q34); Z3HC1 (7q32.3); and CYP17A1 (10q24.3). We have furnished evidence directly implicating the candidacy of these genes, either because the locations of the signals discovered are within a narrow window of linkage disequilibrium or because there is evidence of a mechanistic effect, or both. Second, we have provided large-scale refutation of the relevance of many prominent candidate gene hypotheses in CAD, thereby clarifying the literature. Third, contrary to expectation, we did not observe highly significant novel associations between low frequency variants and CAD risk, despite study of >4,500 such variants. Fourth, we have confirmed the relevance of several previously established CAD genes to both Europeans and South Asians, without finding qualitative differences in results by ethnicity.

LIPA (lipase A) encodes a lysosomal acid lipase involved in the breakdown of cholesteryl esters and triglycerides. Mutations in LIPA cause Wolman's disease [16], a rare disorder characterized by accumulation of these lipids in multiple organs. However, despite evidence that the risk allele was associated with higher LIPA gene expression (suggesting that both under- and over-activity of LIPA increase CAD risk), it was not significantly associated with altered lipid levels. This finding suggests that the impact on CAD risk is either through an alternative pathway, or that the mechanism is more complex than reflected through conventionally measured plasma lipid levels. Two recent studies have also found associations of variants in the LIPA gene with CAD using a GWA approach, strengthening the evidence for this association [17], [18].

Our identification of the association of variants near interleukin 5 (IL5), an interleukin produced by T helper-2 cells, is interesting given the evidence that both acute and chronic inflammation may play important roles in the development and progression of CAD [19]. Most previous human association studies of inflammatory genes and CAD have focused on other cytokines and acute-phase reactants. Nevertheless, some experimental data predict that IL-5 has an atheroprotective effect and this has been supported by association between higher circulating IL-5 levels and lower carotid intimal-medial thickness [20]–[22]. Our findings now highlight the potential importance of IL-5 in CAD, especially as the IL-5 receptor is already a viable therapeutic target in allergic diseases, although we can not rule out the possibility that another gene at this locus may be mediating the association with CAD risk.

The ATP-binding cassette sub-family G proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 are hemi-transporters that limit intestinal absorption and promote biliary excretion of sterols. Mutations in either gene are associated with sitosterolaemia, accumulation of dietary cholesterol and premature atherosclerosis [23]. Recently, common variants in ABCG8 have also been shown to be associated with circulating LDL-C and altered serum phytosterol levels with concordant changes in risk of CAD [15], [24]. Our findings confirm that this locus affects CAD risk either directly through its effect on plasma phytosterol levels or through primary/secondary changes in LDL-cholesterol.

The association signal on 8q24.13 maps near the TRIB1 gene which encodes the Tribbles homolog 1 protein. Tribbles are a family of phosphoproteins implicated in regulation of cell function, although their precise roles are unclear [25]. However, SNPs in or near TRIB1 - including the lead SNP in our study (rs17321515) - have recently been shown to have highly significant associations with levels of several major lipids [15], providing a possible mechanism for their association with CAD. Our findings confirm the previous suggestion that this variant is also associated with CAD risk [15], [26]. Hepatic over-expression of TRIB1 in mice has been shown to lower circulating triglycerides; conversely, targeted deletion of the TRIB1 gene in mice led to higher circulating triglycerides [27]. The location of the CAD-associated variant downstream of TRIB1 suggests that its effect may be mediated by regulation of TRIB1 expression leading to adverse lipid profiles, although we did not find an eQTL at this locus in monocytes.

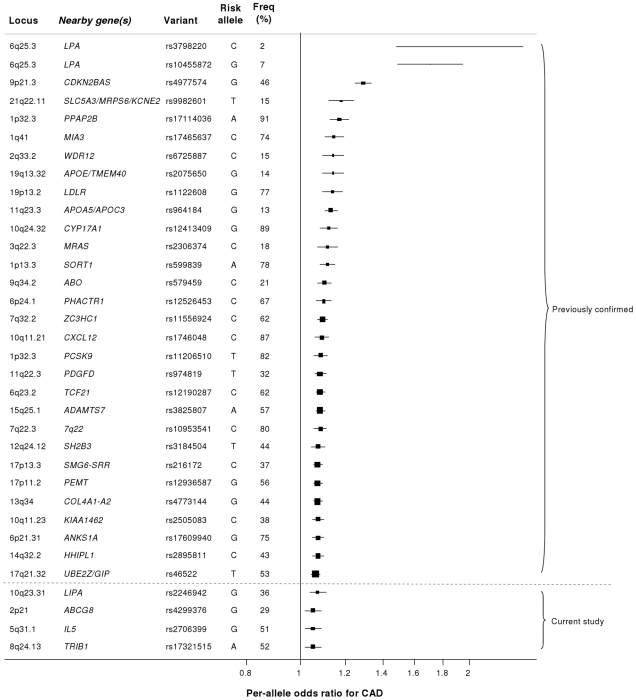

Our study brings to 33 the number of confirmed loci with common variants affecting risk of CAD (Figure 7). We estimate that in aggregate these variants explain about 9% of the heritability of CAD which is consistent with the recent analysis by CARDIoGRAM [12]. Interestingly, the odds ratios that we observed for the novel loci were generally lower than those of previously identified loci. This suggests that most of the common variants with moderate effects have been identified and that increasingly larger sample sizes will be required to detect further common variants that affect risk of CAD. However, the modest odds ratios associated with such variants do not necessarily imply that they are not of potential clinical or therapeutic relevance. For example, there are only modest effects of common variants in the LDLR gene on CAD risk (Figure 7); yet this pathway has become a major target for the prevention and treatment of CAD with the development of statins.

Figure 7. Novel loci identified in this study placed in the context of previously confirmed CAD loci.

Previously reported variants listed are those from the NHGRI GWA studies catalogue [32] reported as having P<5×10−8 with CAD. Per-allele odds ratios and percentage risk allele frequencies (‘Freq’) are those listed in the catalogue. Frequencies and per-allele odds ratios for the novel variants reported in this study (appearing below the dashed line) are from the CARDIoGRAM replication stage.

Despite the success of the GWA approach in identifying several common variants that affect risk of CAD, such loci explain only a small proportion of the heritability of CAD [5]. It has been hypothesized that some of the unexplained heritability resides in lower frequency (1–5%) variants which are not adequately represented on current genomewide arrays and/or are difficult to impute from GWA data. Because the gene array used in the current study included ∼4500 lower frequency variants as well as known functional variants for the majority of the genes on the array, we were able to examine this issue for CAD, at least in relation to candidate cardiovascular genes. Although we confirmed the previously reported associations of lower frequency variants in LPA and PCSK9 with CAD risk, we did not detect any other strongly associated variants in the 1–5% range or an enrichment of low frequency variants amongst SNPs that showed nominal association with CAD. However, it is important to note that rare variants in the genome (minor allele frequency <1%) were not addressed in this study.

CAD is more common in South Asians and tends to occur at an earlier age than in Europeans, perhaps partly due to genetic factors [28]. Our study provides the first systematic exploration of this issue. We observed a weaker effect size for the 9p21.3 locus in South Asians compared with Europeans, although this did not appear to be related to any obvious differences in haplotype structure at the locus, confirming recent findings in Pakistanis [29]. This difference in effect size between ethnic groups will require further evaluation and replication as other differences between the European and South Asian studies (eg, different sex distributions) could explain this finding. Most of the other disease-associated variants we found had slightly weaker effects in South Asians, although, because power to detect heterogeneity of effect between the ethnicities was low and there were only 2 South Asian studies, this finding will require further evaluation. We observed variants at 3 loci (TUB, LCT and MICB, Table S5) which showed modest (P<10−4) associations in South Asians but were convincingly null in Europeans and will therefore require replication in additional South Asian samples. Overall, we did not find clear evidence of major variation in genetic risk factors for CAD between Europeans and South Asians.

In summary, using a large-scale gene-centric approach we have identified novel associations of several genes for CAD that relate to diverse biochemical and cellular functions, including inflammation and novel lipid pathways, as well as genes of less certain function. Together, these findings indicate that previously unsuspected biological mechanisms operate in CAD, raising prospects for novel approaches to intervention.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Characteristics of the discovery phase studies are summarised in Table 1, Table S1 and the replication studies in Table S6. Further details of all the studies are given in Text S1. All individuals provided informed consent and all studies were approved by local ethics committees.

Genotyping in discovery cohorts

Using the HumanCVD BeadChip array (Illumina), which is also known as the “ITMAT-Broad-CARe” (IBC) 50K array, we genotyped 49,094 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ∼2,100 candidate genes identified in previous studies of cardiovascular disease, pathway-based approaches (including genes related to metabolism, lipids, thrombosis, circulation and inflammation), early access to GWA datasets for CAD, type 2 diabetes, lipids and hypertension, as well as human and mouse gene expression data [10]. Variants in genes suspected to be associated with sleep, lung and blood disease phenotypes were also included, along with SNPs that were related in GWA datasets to rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and type 1 diabetes. Human and mouse gene expression data was also used to select variants. Genes were then prioritised by investigators, with ‘high priority genes’ densely tagged (all SNPs with MAF>2% tagged at r2>0.8), ‘intermediate priority genes’ moderately covered (all SNPs with MAF>5% tagged at r2>0.5), and ‘low priority genes’ tagged using only non-synonymous SNPs and known functional variants with MAF>1%.

A “cosmopolitan tagging” approach was used to select SNPs providing high coverage of selected genes in 4 HapMap populations (CEPH Caucasians, Han Chinese, Japanese, Yorubans). For all genes, non-synonymous SNPs and known functional variants were prioritised on the array. Genotypes were called using standard algorithms (eg, GenCall Software and Illuminus) and standard quality control methods were applied to filter out poorly performing or rare (<1% minor allele frequency) SNPs (Text S1). After exclusion of low frequency variants (average 8,354 in each study), non-autosomal variants (average 1,224) and variants that failed quality control (average 842 – predominantly due to high missingness or failure of HWE), the number of SNPs taken forward for analysis in each study ranged from 30,550–39,027 (Table S2).

Statistical analysis

In each study, unadjusted logistic regression tests using a case-control design assuming an additive genetic model were conducted, with most studies using PLINK [30]. All studies made attempts to reduce over-dispersion. The genomic inflation factor for each study after adjustment was <1.10 with one exception (Table S2). The primary analysis was a fixed-effect inverse-variance-weighted meta-analysis performed separately for each ethnic group using STATA v11. A chi-squared test for between-ethnicity heterogeneity was performed. A secondary analysis combined European and South Asian studies to identify additional variants common to both ethnicities (Text S1).

Replication

Based on a simulation study conducted prior to the analysis (Figure S2), variants were selected for the replication stage if they had an unadjusted P<1×10−4 in either the primary analysis or the combined ethnicity analysis. Only the most significant (“lead”) SNP from each locus was taken forward for replication. SNPs at known coronary disease risk loci (eg, 9p21.3, LPA, APOE) were excluded from the replication stage, leaving 27 SNPs to take forward. In silico replication was conducted using non-overlapping participants from the CARDIoGRAM GWA meta-analysis [12] of CAD plus an additional study, EPIC-NL [31] (details in Table S6). In total, the replication stage comprised up to 17,121 coronary disease cases and 40,473 controls. The threshold for independent replication was a 1-tailed Bonferroni-corrected P<0.05 (P<1.9×10−3) from a Cochran-Armitage trend test. P values from the replication and discovery stages were combined using Fisher's method with a chip-wide value of P<3×10−6 considered to be statistically significant based on the simulation study (Figure S2). Adjusted P values accounting for both over-dispersion and heterogeneity in the discovery stage studies were also estimated through correction for study- and meta-analysis-specific inflation factors.

Additional analyses

To check for consistency of effect of variants that replicated, subgroup analyses were performed in the discovery stage studies for MI cases only, CAD cases aged less than 50, males only and females only. Replicating SNPs were tested for association with known cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure, lipids levels and type 2 diabetes mellitus using existing large-scale GWA meta-analyses data of these traits [13]–[15]. We also assessed the association of these variants with gene expression in circulating monocytes taken from 363 patients with premature myocardial infarction and 395 healthy blood donors (Text S1). To put novel findings from this study in the context of existing knowledge, we summarised associations of common variants established in CAD (P<5×10−8) using available information from the NHGRI's GWA studies catalogue [32].

Supporting Information

Power to detect associated variants in discovery and replication stages. Power to detect an association with alpha = 10−4 (two-sided) assuming a per-allele effect and a discovery stage study size of 11,202 coronary disease cases and 30,733 controls (equivalent to the European studies in the discovery stage) across a range of minor allele frequencies (1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, 5%, 10%). These power calculations assume that there is no between-study heterogeneity. Power to detect an association with alpha = 1.9×10−3 (one-sided) assuming a per-allele effect and a replication stage study size of 17,121 coronary disease cases and 40,473 controls (equivalent to the whole replication stage) range of minor allele frequencies (5%, 10%, 25%, 50%). These power calculations assume that there is no between-study heterogeneity.

(PDF)

Simulated distribution of P values from discovery stage meta-analyses. The distribution of the number of SNPs with a P value<10−4 under the null hypothesis of no associated SNPs is based on 50,000 simulations using the controls from the BHF-FHS study. The median is 2 significant SNPs (mean 2.5), suggesting that using this threshold for taking SNPs to the replication stage is likely to result in few false positives. The comparable numbers for a threshold of P<10−3 are median = 27 (mean 27), whilst the mean was 0.25 for P<10−5. The distribution of lowest P value in each simulation across the Human CVD Beadchip array is based on 50,000 simulations using the controls from the BHF-FHS study. The vertical line at P = 3×10−6 represents the 5th percentile, which was selected to denote chip-wide significance.

(PDF)

Forest plots for novel SNPs in discovery stage studies. Forest plots denote study-specific per-allele estimates of risk of CAD, with the centre of each box representing the odds ratio, the area of the box proportional to the weight (the inverse of the variance), and the horizontal line indicating the 95% confidence interval. Log odds ratios and standard errors were pooled using a fixed-effect meta-analysis. Open diamonds represent pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals. European and South Asian subgroup analyses did not differ significantly from each other for any of the SNPs displayed.

(PDF)

Subgroup analyses for novel loci in European discovery stage studies. Allele = Allele associated with increased risk of CAD; Freq = frequency of risk allele in control populations. MI = MI cases only vs all controls; Young = CAD cases diagnosed aged less than 50 years.

(PDF)

Details of studies included in the discovery stage. - denotes ‘not applicable’ or ‘not available’. All values are means (±SD) unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not be of all available individuals due to missing data. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities; BHF-FHS = British Heart Foundation Family Heart Study; CARDIA = Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults; CHS = Cardiovascular Health Study; FHS = Framingham Heart Study; LOLIPOP = London Life Sciences Prospective Population Cohort; PROCARDIS = Precocious Coronary Artery Disease; PROMIS = Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study. * age at baseline. 4 studies (BHF-FHS, MONICA-KORA, PennCATH and PROMIS) used version 1 (V1) of the array, whilst the other 8 used version 2 (V2). V2 contains an additional 132 genes (3,857 SNPs) hence SNPs on V2 were only analysed in studies that used the V2 array. Participants in the Framingham Heart Study were drawn from the Offspring and Third Generation cohorts.

(PDF)

Quality control information for SNPs in discovery stage studies. Inflation factor = ratio of median observed chi2 value to that expected under the null hypothesis; MAF = minor allele frequency; No result = no odds ratio obtained from model, generally due to low MAF; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P value estimated for controls only).

(PDF)

Results for all loci meeting P<10−3 in discovery stage meta-analyses. SNPs are ordered by ascending P value in the combined meta-analysis. Only the lead SNP (with the lowest P value) from each locus is shown unless different SNPs met the threshold in Europeans/South Asians. Data shown are per-allele odds ratios from unadjusted fixed-effect inverse-variance meta-analysis of 10 European studies, 2 South Asians studies and 12 studies combined. Loci highlighted in grey are those previously identified by GWA studies; loci highlighted in yellow are additional loci considered to be known CAD risk loci.

(PDF)

Associations with previously studied candidate variants. Variants ordered by biological pathway, then gene. Per-allele odds ratios are presented for the effect allele, which is the minor allele in European populations. r2 with best imputed proxy was estimated using ∼2.5 M directly genotyped or HapMap-imputed SNPs in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium. Tagging levels are 1 (r2>0.8 with all HapMap/Seattle SNPs of MAF≥0.02), 2 (r2>0.5 with all HapMap/Seattle SNPs of MAF≥0.05), 3 (only non-synonymous and known functional variants of MAF>0.01) and GWAS (specific SNPs previously identified in recent GWAS). a rs4343 has r2 = 1 with the insertion/deletion polymorphism in the ACE gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. b rs17443251 has r2 = 0.75 with the more commonly studied R144C variant (rs1799853) in the CYP2C9 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. c rs9526246 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied T102C variant (rs6313) in the HTR2A gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. d rs1062535 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied C807T variant (rs1126643) in the ITGA2 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. e rs1805096 has r2 = 0.89 with the more commonly studied rs6700896 variant in the LEPR gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. f rs1049897 has r2 = 1 with the more commonly studied A102T variant (rs4236) in the MGP gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. g rs4968624 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied L125V variant (rs668) in the PECAM1 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. h rs12944077 has r2 = 1 with the more commonly studied S563N variant (rs12953) in the PECAM1 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population.

(PDF)

27 loci meeting P<1×10−4 threshold in discovery stage meta-analyses. Lead SNP = SNP with lowest P-value at this locus; risk allele = allele associated with increased CAD risk according to forward strand; freq = frequency of risk allele pooled across controls; OR = per-allele odds ratio for risk allele; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval around odds ratio; P = P value from fixed-effect meta-analysis; Combined = 10 European studies and 2 South Asian studies combined in a single fixed-effect meta-analysis; Overall = P values from discovery stage and replication stage combined; P_adj = P value adjusted for both study-specific and meta-analysis inflation factors in the discovery stage; SNPs ordered by ascending P value. * For 3 loci (ZC3HC1, CYP17A1, COL4A1/COL4A2), replication data are not presented here, however genome-wide significant associations at these loci are reported in the paper by the CARDIoGRAM Consortium.

(PDF)

Details of studies included in the replication stage. All values are means (±SD) unless otherwise stated.

(PDF)

Expression QTL (eQTL) analysis for novel CAD loci. a. eQTL analysis for novel CAD loci. †Key (Proportion of all Probes). 1 = Weak (0%–20%). 2 = Medium (20%–80%). 3 = Strong (80%–100%). b. Conditional analysis of expression QTL (eQTL) loci. Conditional analysis of the lead LIPA SNP on a secondary SNP at the same locus that is also associated with gene expression shows that the lead SNP at the LIPA locus has a strong independent effect on LIPA expression levels. Conditional analysis of the lead IL5 SNP on a second nearby SNP that is also associated with RAD50 gene expression shows that the observed eQTL association with the IL5 SNP is probably due to LD with the RAD50 SNP.

(PDF)

Comparison of haplotype frequencies for novel loci in European and South Asian controls. Haplotypes are displayed in decreasing frequency, with the same haplotype order in both ethnicities. * = haplotype frequencies in bold are those containing the CAD risk-associated allele of the lead SNP. SNPs were selected for inclusion in the haplotype if they had r2≥0.5 in either the European or the South Asian controls. The 3330 PROCARDIS controls were used to represent the European populations, whilst the PROMIS controls were used to represent the South Asian population. Only haplotypes that were common (frequency>5%) in at least one population are displayed.

(PDF)

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References, Supplementary Acknowledgements.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the DIAGRAM Consortium, the Global Lipids Consortium, and the GlobalBPGen Consortium for providing information on associations of SNPs with cardiovascular risk factors. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the research institutions, study investigators, field staff, and participants in each of the contributing studies.

Dr. Butterworth and Professors Samani, Danesh, and Watkins had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analyses.

Contributors List

Adam S Butterworth1 , Peter S Braund2,3

, Peter S Braund2,3 , Martin Farrall4

, Martin Farrall4 , Robert J Hardwick2,3,5, Danish Saleheen1,6, John F Peden4, Nicole Soranzo7, John C Chambers8, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam9, Marcus E Kleber10, Brendan Keating11, Atif Qasim12, Norman Klopp13, Jeanette Erdmann14, Themistocles L Assimes15, Stephen G Ball16, Anthony J Balmforth17, Timothy A Barnes2,3, Hanneke Basart9, Jens Baumert13, Connie R Bezzina18, Eric Boerwinkle19, Bernhard O Boehm20, Jessy Brocheton21, Peter Bugert22, Francois Cambien21, Robert Clarke23, Veryan Codd2,3, Rory Collins23, David Couper24, L Adrienne Cupples25,26, Jonas S de Jong18, Patrick Diemert14, Kenechi Ejebe27, Clara C Elbers28,29, Paul Elliott30, Myriam Fornage31, Maria-Grazia Franzosi32, Philippe Frossard6, Stephen Garner33,34, Anuj Goel4, Alison H Goodall2,3, Christian Hengstenberg35, Sarah E Hunt7, John JP Kastelein9, Olaf H Klungel36, Harald Klüter22, Kerstin Koch33,34, Inke R König37, Angad S Kooner38, Reijo Laaksonen39, Mark Lathrop40,41, Mingyao Li42, Kiang Liu43, Ruth McPherson44, Muntaser D Musameh2,3, Solomon Musani45, Christopher P Nelson2,3, Christopher J O'Donnell26,46,47, Halit Ongen4, George Papanicolaou48, Annette Peters13, Bas JM Peters36, Simon Potter7, Bruce M Psaty49,50, Liming Qu42, Daniel J Rader12,51, Asif Rasheed6, Catherine Rice7, James Scott38, Udo Seedorf52, Joban S Sehmi38, Nona Sotoodehnia53,54, Klaus Stark35, Jonathan Stephens33,34, C Ellen van der Schoot55, Yvonne T van der Schouw28, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir56, Maciej Tomaszewski2,3, Pim van der Harst2,3, Ramachandran S Vasan57,58,59, Arthur AM Wilde18, Christina Willenborg14, Bernhard R Winkelmann60, Moazzam Zaidi6, Weihua Zhang8, Andreas Ziegler37, Paul IW de Bakker28,29,61,62, Wolfgang Koenig63, Winfried März64,65,66, Mieke D Trip9,18, Muredach P Reilly12,48, Sekar Kathiresan27,61, Heribert Schunkert14, Anders Hamsten67, Alistair S Hall68, Jaspal S Kooner38, Simon G Thompson1,69, John R Thompson70, Panos Deloukas7, Willem H Ouwehand7,33,34‡, Hugh Watkins4‡, John Danesh1‡, Nilesh J Samani2,3‡.

, Robert J Hardwick2,3,5, Danish Saleheen1,6, John F Peden4, Nicole Soranzo7, John C Chambers8, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam9, Marcus E Kleber10, Brendan Keating11, Atif Qasim12, Norman Klopp13, Jeanette Erdmann14, Themistocles L Assimes15, Stephen G Ball16, Anthony J Balmforth17, Timothy A Barnes2,3, Hanneke Basart9, Jens Baumert13, Connie R Bezzina18, Eric Boerwinkle19, Bernhard O Boehm20, Jessy Brocheton21, Peter Bugert22, Francois Cambien21, Robert Clarke23, Veryan Codd2,3, Rory Collins23, David Couper24, L Adrienne Cupples25,26, Jonas S de Jong18, Patrick Diemert14, Kenechi Ejebe27, Clara C Elbers28,29, Paul Elliott30, Myriam Fornage31, Maria-Grazia Franzosi32, Philippe Frossard6, Stephen Garner33,34, Anuj Goel4, Alison H Goodall2,3, Christian Hengstenberg35, Sarah E Hunt7, John JP Kastelein9, Olaf H Klungel36, Harald Klüter22, Kerstin Koch33,34, Inke R König37, Angad S Kooner38, Reijo Laaksonen39, Mark Lathrop40,41, Mingyao Li42, Kiang Liu43, Ruth McPherson44, Muntaser D Musameh2,3, Solomon Musani45, Christopher P Nelson2,3, Christopher J O'Donnell26,46,47, Halit Ongen4, George Papanicolaou48, Annette Peters13, Bas JM Peters36, Simon Potter7, Bruce M Psaty49,50, Liming Qu42, Daniel J Rader12,51, Asif Rasheed6, Catherine Rice7, James Scott38, Udo Seedorf52, Joban S Sehmi38, Nona Sotoodehnia53,54, Klaus Stark35, Jonathan Stephens33,34, C Ellen van der Schoot55, Yvonne T van der Schouw28, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir56, Maciej Tomaszewski2,3, Pim van der Harst2,3, Ramachandran S Vasan57,58,59, Arthur AM Wilde18, Christina Willenborg14, Bernhard R Winkelmann60, Moazzam Zaidi6, Weihua Zhang8, Andreas Ziegler37, Paul IW de Bakker28,29,61,62, Wolfgang Koenig63, Winfried März64,65,66, Mieke D Trip9,18, Muredach P Reilly12,48, Sekar Kathiresan27,61, Heribert Schunkert14, Anders Hamsten67, Alistair S Hall68, Jaspal S Kooner38, Simon G Thompson1,69, John R Thompson70, Panos Deloukas7, Willem H Ouwehand7,33,34‡, Hugh Watkins4‡, John Danesh1‡, Nilesh J Samani2,3‡.

1) Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

2) Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK

3) Leicester National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK

4) Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

5) Department of Genetics, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

6) Center for Non-Communicable Diseases, Karachi, Pakistan

7) Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, UK

8) Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Imperial College London, St Mary's Campus, Norfolk Place, London, UK

9) Department of Vascular Medicine, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

10) LURIC non profit LLC, Freiburg, Germany

11) Center for Applied Genomics, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

12) Cardiovascular Institute, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

13) Institute of Epidemiology II, Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany

14) Universität zu Lübeck, Medizinische Klinik II, Lübeck, Germany

15) Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

16) LIGHT Research Institute, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

17) Division of Cardiovascular and Diabetes Research, Multidisciplinary Cardiovascular Research Centre, Leeds Institute of Genetics, Health and Therapeutics, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

18) Heart Failure Research Centre, Department of Clinical and Experimental Cardiology, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

19) Human Genetics Center and Institute of Molecular Medicine, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA

20) Division of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Centre of excellence “Metabolic Diseases”, Baden-Wuerttemberg, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany

21) INSERM UMRS 937, Pierre and Marie Curie University (UPMC, Paris 6) and Medical School, Paris, France

22) Institute of Transfusion Medicine and Immunology, Medical Faculty Mannheim, Heidelberg University, Germany Red Cross Blood Service of Baden-Württemberg - Hessen gGmbH, Mannheim, Germany

23) Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

24) Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

25) Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

26) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute's Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA

27) Cardiovascular Research Center and Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

28) Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

29) Department of Medical Genetics, Division of Biomedical Genetics, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

30) MRC-HPA Centre for Environment and Health, Imperial College London, London, UK

31) Institute of Molecular Medicine, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA

32) Department of Cardiovascular Research, Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri, Milan, Italy

33) Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

34) NHS Blood and Transplant, Cambridge, UK

35) Klinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin II, Universität Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

36) Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht, the Netherlands

37) Institut für Medizinische Biometrie und Statistik, Universität zu Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

38) Hammersmith Hospital, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK

39) Science Center, Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland

40) Commissariat à l'énergie atomique – Institut de Génomique - Centre National de Genotypage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP 5721, 91057, Evry Cedex, France

41) Fondation Jean Dausset – CEPH, 27 rue Juliette Dodu, 75010, Paris, France

42) Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

43) Department of Preventive Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

44) The John & Jennifer Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

45) University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA

46) Cardiology Division, Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

47) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA

48) Division of Prevention and Population Sciences, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

49) Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, Departments of Medicine, Epidemiology, and Health Services, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

50) Group Health Research Institute, Group Health Cooperative, Seattle, WA, USA

51) Institute of Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA, USA

52) Leibniz-Institut für Arterioskleroseforschung an der Universität Münster, Münster, Germany

53) Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

54) Division of Cardiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

55) Department of Experimental Immunohematology, Sanquin Research, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

56) deCODE Genetics, 101 Reykjavik, Iceland

57) Echocardiography/Vascular Laboratory, Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA

58) Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

59) Section of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology, Dept of Medicine, Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA

60) Cardiology Group Frankfurt-Sachsenhausen, Frankfurt and ClinPhenomics GmbH, Dannstadt, Frankfurt, Germany

61) Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA

62) Division of Genetics, Department of Medicine, Brigham's and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

63) Department of Internal Medicine II-Cardiology, University of Ulm Medical Center, Ulm, Germany

64) Synlab Services GmbH, Mannheim, Germany

65) Clinical Institute of Medical and Chemical Laboratory Diagnostics, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria

66) Institute of Public Heath, Social Medicine and Epidemiology, Medical Faculty Mannheim, University of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Germany

67) Atherosclerosis Research Unit, Department of Medicine Solna, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

68) Division of Cardiovascular and Neuronal Remodelling, Multidisciplinary Cardiovascular Research Centre, Leeds Institute of Genetics, Health and Therapeutics, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

69) Medical Research Council Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK

69) Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK

These authors contributed equally to this work.

These authors contributed equally to this work.

‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Study Collaborators (by study ordered alphabetically)

Discovery stage studies

BHF-FHS: Timothy Barnes, Suzanne Rafelt, Veryan Codd, Maciej Tomaszewski, Willem H Ouwehand

BLOODOMICS-Dutch: AGNES - Nienke Bruinsma, Lukas R Dekker, José P Henriques, Karel T Koch, Robbert J de Winter, Marco Alings, Cor F Allaart, Anton P Gorgels, Freek W Verheugt

LOLIPOP: Leicester: Peter S Braund, John R Thompson, Nilesh J Samani

MONICA-KORA: Martina Mueller, Christa Meisinger

PennCATH: Stephanie DerOhannessian, Nehal N Mehta, Jane Ferguson, Hakon Hakonarson, William Matthai, Robert Wilensky

PROCARDIS: JC Hopewell, S Parish, P Linksted, J Notman, H Gonzalez, A Young, T Ostley, A Munday, N Goodwin,V Verdon, S Shah, L Cobb, C Edwards, C Mathews, R Gunter, J Benham, C Davies, M Cobb, L Cobb, J Crowther, A Richards, M Silver, S Tochlin, S Mozley, S Clark, M Radley, K Kourellias, Angela Silveira, Birgitta Söderholm, Per Olsson, Simona Barlera, Gianni Tognoni, Stephan Rust, Gerd Assmann, Simon Heath, Diana Zelenika, Ivo Gut, Fiona Green, Martin Farrall, John Peden, Anuj Goel, Halit Ongen, Maria-Grazia Franzosi, Mark Lathrop, Udo Seedorf, Robert Clarke, Rory Collins, Anders Hamsten, Hugh Watkins.

PROCARDIS: Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm - Anette Aly, Karolina Anner, Karin Björklund, Gun Blomgren, Barbro Cederschiöld, Karin Danell-Toverud, Per Eriksson, Ulla Grundstedt, Anders Hamsten, Merja Heinonen, Mai-Lis Hellénius, Ferdinand van't Hooft, Karin Husman, Jacob Lagercrantz, Anita Larsson, Malin Larsson, Magnus Mossfeldt, Anders Mälarstig, Gunnar Olsson, Maria Sabater-Lleal, Bengt Sennblad, Angela Silveira, Rona Strawbridge, Birgitta Söderholm, John Öhrvik

PROMIS: Khan Shah Zaman, Nadeem Hayat Mallick, Muhammad Azhar, Abdus Samad, Mohammad Ishaq, Nabi Shah, Maria Samuel

Replication studies+gene expression analyses

CARDIoGRAM: Heribert Schunkert, Inke R König, Sekar Kathiresan, Muredach Reilly, Themistocles L Assimes, Hilma Holm, Michael Preuss, Alexandre FR Stewart, Maja Barbalic, Christian Gieger, Devin Absher, Zouhair Aherrahrou, Hooman Allayee, David Altshuler, Sonia Anand, Karl Andersen, Jeffrey L Anderson, Diego Ardissino, Stephen G Ball, Anthony J Balmforth, Timothy A Barnes, Lewis C Becker, Diane M Becker, Klaus Berger, Joshua C Bis, S Matthijs Boekholdt, Eric Boerwinkle, Peter S Braund, Morris J Brown, Mary Susan Burnett, Ian Buysschaert, John F Carlquist, Li Chen, Veryan Codd, Robert W Davies, George Dedoussis, Abbas Dehghan, Serkalem Demissie, Joseph Devaney, Ron Do, Angela Doering, Nour Eddine El Mokhtari, Stephen G Ellis, Roberto Elosua, James C Engert, Stephen Epstein, Ulf de Faire, Marcus Fischer, Aaron R Folsom, Jennifer Freyer, Bruna Gigante, Domenico Girelli, Solveig Gretarsdottir, Vilmundur Gudnason, Jeffrey R Gulcher, Stephanie Tennstedt, Eran Halperin, Naomi Hammond, Stanley L Hazen, Albert Hofman, Benjamin D Horne, Thomas Illig, Carlos Iribarren, Gregory T Jones, J Wouter Jukema, Michael A Kaiser, Lee M Kaplan, John JP Kastelein, Kay-Tee Khaw, Joshua W Knowles, Genovefa Kolovou, Augustine Kong, Reijo Laaksonen, Diether Lambrechts, Karin Leander, Mingyao Li, Wolfgang Lieb, Patrick Diemert, Guillaume Lettre, Christina Loley, Andrew J Lotery, Pier M Mannucci, Seraya Maouche, Nicola Martinelli, Pascal P McKeown, Christa Meisinger, Thomas Meitinger, Olle Melander, Pier Angelica Merlini, Vincent Mooser, Thomas Morgan, Thomas W Mühleisen, Joseph B Muhlestein, Kiran Musunuru, Janja Nahrstaedt, Christopher P Nelson, Markus M Nöthen, Oliviero Olivieri, Flora Peyvandi, Riyaz S Patel, Chris C Patterson, Annette Peters, Liming Qu, Arshed A Quyyumi, Daniel J Rader, Loukianos S Rallidis, Catherine Rice, Frits R Roosendaal, Diana Rubin, Veikko Salomaa, M Lourdes Sampietro, Manj S Sandhu, Eric Schadt, Arne Schäfer, Arne Schillert, Stefan Schreiber, Jürgen Schrezenmeir, Stephen M Schwartz, David S Siscovick, Mohan Sivananthan, Suthesh Sivapalaratnam, Albert V Smith, Tamara B Smith, Jaapjan D Snoep, Nicole Soranzo, John A Spertus, Klaus Stark, Kari Stefansson, Kathy Stirrups, Monika Stoll, WH Wilson Tang, Gudmundur Thorgeirsson, Gudmar Thorleifsson, Maciej Tomaszewski, Andre G Uitterlinden, Andre M van Rij, Benjamin F Voight, Nick J Wareham, George A Wells, H-Erich Wichmann, Christina Willenborg, Jaqueline CM Witteman, Benjamin J Wright, Shu Ye, Andreas Ziegler, Francois Cambien, Alison H Goodall, L Adrienne Cupples, Thomas Quertermous, Winfried März, Christian Hengstenberg, Stefan Blankenberg, Willem H Ouwehand, Alistair S Hall, Panos Deloukas, Unnur Thorsteinsdottir, Robert Roberts, John R Thompson, Christopher J O'Donnell, Ruth McPherson, Jeanette Erdmann, Nilesh J Samani.

EPIC-NL: N Charlotte Onland-Moret, Jessica van Setten, Paul IW de Bakker, WM Monique Verschuren, Jolanda MA Boer, Cisca Wijmenga, Marten H Hofker

UCP: Anke-Hilse Maitland-van der Zee, Anthonius de Boer, Diederick E Grobbee

Cardiogenics: Tony Attwood, Stephanie Belz, Peter Braund, François Cambien, Jason Cooper, Abi Crisp-Hihn, Patrick Diemert, Panos Deloukas, Nicola Foad, Jeanette Erdmann, Alison H Goodall, Jay Gracey, Emma Gray, Rhian Gwilliams, Susanne Heimerl, Christian Hengstenberg, Jennifer Jolley, Unni Krishnan, Heather Lloyd-Jones, Ingrid Lugauer, Per Lundmark, Seraya Maouche, Jasbir S Moore, David Muir, Elizabeth Murray, Chris P Nelson, Jessica Neudert, David Niblett, Karen O'Leary, Willem H Ouwehand, Helen Pollard, Angela Rankin, Catherine M Rice, Hendrik Sager, Nilesh J Samani, Jennifer Sambrook, Gerd Schmitz, Michael Scholz, Laura Schroeder, Heribert Schunkert, Ann-Christine Syvannen, Stephanie Tennstedt, Chris Wallace

Footnotes

Muredach P Reilly and Daniel J Rader have a research grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Clinical Pharmacology employing Bas Peters, Olaf Klungel, Anthonius de Boer, and Anke-Hilse Maitland-van der Zee has received unrestricted funding for pharmacoepidemiological research from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, the private-public funded Top Institute Pharma (www.tipharma.nl, includes co-funding from universities, government, and industry), the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board, and the Dutch Ministry of Health. Arthur AM Wilde is a consultant for Transgenomics (Familion test) and Sorin. No other disclosures were reported.

BHF-FHS: Recruitment of CAD cases for the BHF-FHS study was supported by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) and the UK Medical Research Council. Controls were provided by the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genotyping of the IBC 50K array for the BHF-FHS study was funded by the BHF. NJS and SGB hold personal chairs supported by the BHF. The work described in this paper forms part of the portfolio of translational research supported by the Leicester NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease. BLOODOMICS: The Bloodomics partners from AMC (The Netherlands), LURIC (Germany), the University of Cambridge (UK), and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (UK) received funding through the 6th Framework funded Integrated Project Bloodomics (grant LSHM-CT-2004-503485). The University of Cambridge group in the Department of Haematology also received programme grant funding from the British Heart Foundation (RG/09/12/28096) and the National Institute for Health Research (RP-PG-0310-1002). BLOODOMICS-Dutch: This study was supported by research grants from The Netherlands Heart Foundation (grants 2001D019, 2003T302 and 2007B202), the Leducq Foundation (grant 05-CVD), the Center for Translational Molecular Medicine (CTMM COHFAR), and the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of The Netherlands (project 27). BLOODOMICS-German: LURIC has received funding through the 6th Framework Program (integrated project Bloodomics, grant LSHM-CT-2004-503485) and 7th Framework Program (integrated project Atheroremo, Grant Agreement number 201668) of the European Union. CARe Consortium: CARe was performed with the support of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and acknowledges the contributions of the research institutions, study investigators, and field staff in creating this resource for biomedical research. Full details of the studies in the CARe Consortium can be found in Text S1. LOLIPOP: Genotyping of the IBC 50K array for the LOLIPOP Study was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Paul Elliott is a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator. MONICA-KORA: The MONICA/KORA Augsburg studies were financed by the Helmholtz Zentrum München, German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany, and supported by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). Part of this work was financed by the German National Genome Research Network (NGFNPlus, project number 01GS0834) and through additional funds from the University of Ulm. Furthermore, the research was supported within the Munich Center of Health Sciences (MC Health) as part of LMU innovative. PennCATH: Muredach P Reilly and Daniel J Rader have been supported by the Penn Cardiovascular Institute and GlaxoSmithKline. PROCARDIS: The PROCARDIS study has been supported by the British Heart Foundation, the European Community Sixth Framework Program (LSHM-CT-2007-037273), AstraZeneca, the Wellcome Trust, the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, the Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation, the Swedish Medical Research Council, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg Foundation, the Strategic Cardiovascular Program of Karolinska Institutet and Stockholm County Council, the Foundation for Strategic Research and the Stockholm County Council (560283). PROMIS: Epidemiological field work in PROMIS was supported by unrestricted grants to investigators at the University of Cambridge and in Pakistan. Genotyping for this study was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the EU Framework 6–funded Bloodomics Integrated Project (LSHM-CT-2004-503485). The British Heart Foundation has supported some biochemical assays. The Yousef Jameel Foundation supported D Saleheen. The cardiovascular disease epidemiology group of J Danesh is underpinned by programme grants from the British Heart Foundation and the UK Medical Research Council. EPIC-NL: The EPIC-NL study was funded by “Europe against Cancer” Programme of the European Commission (SANCO); the Dutch Ministry of Health; the Dutch Cancer Society; ZonMW the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development; World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF). We thank the institute PHARMO for follow-up data on diabetes. Genotyping was funded by IOP Genomics grant IGE 05012 from NL Agency. UCP: The project was funded by Veni grant Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), Grant no. 2001.064 Netherlands Heart Foundation (NHS), and TI Pharma Grant T6-101 Mondriaan. Cardiogenics: Cardiogenics was funded through the 6th Framework Programme (integrated project Cardiogenics, grant LSHM-CT-2006-037593) of the European Union. None of the sponsors had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium. Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, Hengstenberg C, Mangino M, et al. Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:443–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Gretarsdottir S, Blondal T, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science. 2007;316:1491–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.1142842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, Stewart A, Roberts R, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science. 2007;316:1488–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1142447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdmann J, Grosshennig A, Braund PS, König IR, Hengstenberg C, et al. New susceptibility locus for coronary artery disease on chromosome 3q22.3. Nat Genet. 2009;41:280–282. doi: 10.1038/ng.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tregouet DA, König IR, Erdmann J, Munteanu A, Braund PS, et al. Genome-wide haplotype association study identifies the SLC22A3-LPAL2-LPA gene cluster as a risk locus for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:283–285. doi: 10.1038/ng.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdmann J, Willenborg C, Nahrstaedt J, Preuss M, König IR, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a new locus for coronary artery disease on chromosome 10p11.23. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:158–168. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly MP, Li M, He J, Ferguson JF, Stylianou IM, et al. Identification of ADAMTS7 as a novel locus for coronary atherosclerosis and association of ABO with myocardial infarction in the presence of coronary atherosclerosis: two genome-wide association studies. Lancet. 2011;377:383–392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keating BJ, Tischfield S, Murray SS, Bhangale T, Price TS, et al. Concept, design and implementation of a cardiovascular gene-centric 50 k SNP array for large-scale genomic association studies. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schunkert H, König IR, Kathiresan S, Reilly MP, Assimes TL, et al. Large-scale association analyses identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:333–338. doi: 10.1038/ng.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, Tobin MD, Bochud M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:666–676. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pisciotta L, Fresa R, Bellocchio A, Pino E, Guido V, et al. Cholesteryl Ester Storage Disease (CESD) due to novel mutations in the LIPA gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2009;97:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Coronary Artery Disease (C4D) Genetics Consortium. A genome-wide association study in Europeans and South Asians reveals five novel loci for coronary disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:339–344. doi: 10.1038/ng.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wild PS, Zeller T, Schillert A, Szymczak S, Sinning CR, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies LIPA as a susceptibility gene for coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958728. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binder CJ, Hartvigsen K, Chang MK, Miller M, Broide D, et al. IL-5 links adaptive and natural immunity specific for epitopes of oxidized LDL and protects from atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:427–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI20479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sampi M, Ukkola O, Paivansalo M, Kesaniemi YA, Binder CJ, Horkko S. Plasma interleukin-5 levels are related to antibodies binding to oxidized low-density lipoprotein and to decreased subclinical atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1370–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taleb S, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Adaptive T cell immune responses and atherogenesis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, et al. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teupser D, Baber R, Ceglarek U, Scholz M, Illig T, et al. Genetic regulation of serum phytosterol levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:331–339. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.907873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hegedus Z, Czibula A, Kiss-Toth E. Tribbles: a family of kinase-like proteins with potent signalling regulatory function. Cell Signal. 2007;19:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterworth DM, Ricketts SL, Song K, Chen L, Zhao JH, et al. Genetic variants influencing circulating lipid levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2264–2276. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burkhardt R, Toh S-A, Lagor WR, Birkeland A, Levin M, et al. Trib1 is a lipid- and myocardial infarction-associated gene that regulates hepatic lipogenesis and VLDL production in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4410–4414. doi: 10.1172/JCI44213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhopal R. What is the risk of coronary heart disease in South Asians? A review of UK research. J Public Health Med. 2000;22:375–385. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleheen D, Alexander M, Rasheed A, Wormser D, Soranzo N, et al. Association of the 9p21.3 locus with risk of first-ever myocardial infarction in Pakistanis: case-control study in South Asia and updated meta-analysis of Europeans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1467–1473. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.197210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beulens JW, Monninkhof EM, Verschuren WM, van der Schouw YT, Smit J, et al. Cohort Profile: The EPIC-NL study. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:1170–1178. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, Ramos EM, Mehta JP, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9362–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Power to detect associated variants in discovery and replication stages. Power to detect an association with alpha = 10−4 (two-sided) assuming a per-allele effect and a discovery stage study size of 11,202 coronary disease cases and 30,733 controls (equivalent to the European studies in the discovery stage) across a range of minor allele frequencies (1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, 5%, 10%). These power calculations assume that there is no between-study heterogeneity. Power to detect an association with alpha = 1.9×10−3 (one-sided) assuming a per-allele effect and a replication stage study size of 17,121 coronary disease cases and 40,473 controls (equivalent to the whole replication stage) range of minor allele frequencies (5%, 10%, 25%, 50%). These power calculations assume that there is no between-study heterogeneity.

(PDF)

Simulated distribution of P values from discovery stage meta-analyses. The distribution of the number of SNPs with a P value<10−4 under the null hypothesis of no associated SNPs is based on 50,000 simulations using the controls from the BHF-FHS study. The median is 2 significant SNPs (mean 2.5), suggesting that using this threshold for taking SNPs to the replication stage is likely to result in few false positives. The comparable numbers for a threshold of P<10−3 are median = 27 (mean 27), whilst the mean was 0.25 for P<10−5. The distribution of lowest P value in each simulation across the Human CVD Beadchip array is based on 50,000 simulations using the controls from the BHF-FHS study. The vertical line at P = 3×10−6 represents the 5th percentile, which was selected to denote chip-wide significance.

(PDF)

Forest plots for novel SNPs in discovery stage studies. Forest plots denote study-specific per-allele estimates of risk of CAD, with the centre of each box representing the odds ratio, the area of the box proportional to the weight (the inverse of the variance), and the horizontal line indicating the 95% confidence interval. Log odds ratios and standard errors were pooled using a fixed-effect meta-analysis. Open diamonds represent pooled estimates and 95% confidence intervals. European and South Asian subgroup analyses did not differ significantly from each other for any of the SNPs displayed.

(PDF)

Subgroup analyses for novel loci in European discovery stage studies. Allele = Allele associated with increased risk of CAD; Freq = frequency of risk allele in control populations. MI = MI cases only vs all controls; Young = CAD cases diagnosed aged less than 50 years.

(PDF)

Details of studies included in the discovery stage. - denotes ‘not applicable’ or ‘not available’. All values are means (±SD) unless otherwise stated. Percentages may not be of all available individuals due to missing data. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities; BHF-FHS = British Heart Foundation Family Heart Study; CARDIA = Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults; CHS = Cardiovascular Health Study; FHS = Framingham Heart Study; LOLIPOP = London Life Sciences Prospective Population Cohort; PROCARDIS = Precocious Coronary Artery Disease; PROMIS = Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction Study. * age at baseline. 4 studies (BHF-FHS, MONICA-KORA, PennCATH and PROMIS) used version 1 (V1) of the array, whilst the other 8 used version 2 (V2). V2 contains an additional 132 genes (3,857 SNPs) hence SNPs on V2 were only analysed in studies that used the V2 array. Participants in the Framingham Heart Study were drawn from the Offspring and Third Generation cohorts.

(PDF)

Quality control information for SNPs in discovery stage studies. Inflation factor = ratio of median observed chi2 value to that expected under the null hypothesis; MAF = minor allele frequency; No result = no odds ratio obtained from model, generally due to low MAF; HWE = Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P value estimated for controls only).

(PDF)

Results for all loci meeting P<10−3 in discovery stage meta-analyses. SNPs are ordered by ascending P value in the combined meta-analysis. Only the lead SNP (with the lowest P value) from each locus is shown unless different SNPs met the threshold in Europeans/South Asians. Data shown are per-allele odds ratios from unadjusted fixed-effect inverse-variance meta-analysis of 10 European studies, 2 South Asians studies and 12 studies combined. Loci highlighted in grey are those previously identified by GWA studies; loci highlighted in yellow are additional loci considered to be known CAD risk loci.

(PDF)

Associations with previously studied candidate variants. Variants ordered by biological pathway, then gene. Per-allele odds ratios are presented for the effect allele, which is the minor allele in European populations. r2 with best imputed proxy was estimated using ∼2.5 M directly genotyped or HapMap-imputed SNPs in the CARDIoGRAM Consortium. Tagging levels are 1 (r2>0.8 with all HapMap/Seattle SNPs of MAF≥0.02), 2 (r2>0.5 with all HapMap/Seattle SNPs of MAF≥0.05), 3 (only non-synonymous and known functional variants of MAF>0.01) and GWAS (specific SNPs previously identified in recent GWAS). a rs4343 has r2 = 1 with the insertion/deletion polymorphism in the ACE gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. b rs17443251 has r2 = 0.75 with the more commonly studied R144C variant (rs1799853) in the CYP2C9 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. c rs9526246 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied T102C variant (rs6313) in the HTR2A gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. d rs1062535 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied C807T variant (rs1126643) in the ITGA2 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. e rs1805096 has r2 = 0.89 with the more commonly studied rs6700896 variant in the LEPR gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. f rs1049897 has r2 = 1 with the more commonly studied A102T variant (rs4236) in the MGP gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. g rs4968624 has r2 = 0.97 with the more commonly studied L125V variant (rs668) in the PECAM1 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population. h rs12944077 has r2 = 1 with the more commonly studied S563N variant (rs12953) in the PECAM1 gene in CEU HapMap 2 population.

(PDF)