Abstract

Lipid A (a hexaacylated 1,4’ bis-phosphate) is a potent immune stimulant for TLR4/MD-2. Upon lipid A ligation, the TLR4/MD-2 complex dimerizes and initiates signal transduction. Historically, studies also suggested the existence of TLR4/MD-2-independent LPS signaling. Here we define the role of TLR4 and MD-2 in LPS signaling by using genome wide expression profiling in TLR4- and MD-2-deficient macrophages after stimulations with peptidoglycan-free LPS and synthetic E. coli lipid A. Of the 1,396 genes found significantly induced or repressed by any one of the treatments in the wildtype macrophages, none was present in the TLR4-or MD-2-deficient macrophages, confirming that the TLR4/MD-2 complex is the only receptor for endotoxin, and are both absolutely required for responses to LPS. Using a molecular genetics approach, we investigated the mechanism of TLR4/MD-2 activation by combining the known crystal structure of TLR4/MD-2 with computer modeling. The two phosphates on lipid A were predicted to interact extensively with the two positively charged patches on mouse TLR4 according to our murine TLR4/MD-2 activation model. When either positive patch was abolished by mutagenesis into Ala, the responses to LPS and lipid A were almost abrogated. However, the MyD88-dependent and –independent pathways were impaired to the same extent, indicating that the adjuvant activity of monophosphorylated lipid A most likely arises from its decreased potential to induce an active receptor complex, and not more downstream signaling events. Hence, we conclude that ionic interactions between lipid A and TLR4 are essential for optimal LPS receptor activation.

Introduction

Innate immunity provides immediate protection against microbial infections (reviewed in 1). It also provides the second, yet essential, signal for the induction of the adaptive immune response. The innate immune response has the potential to cause serious complications resulting from microbial invasion, such as the sepsis syndrome. Indeed, about half of all cases of septic shock result from Gram-negative bacterial infections, with an approximate mortality of 25% (2). Numerous attempts to design biological modifying drugs to alleviate the sepsis syndrome have had only limited success (3–7). A detailed understanding of Gram-negative bacterial recognition can provide new insights into how we might better modify the outcome of Gram-negative sepsis.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also known as endotoxin, is the pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) on Gram-negative bacteria that activates the innate immune response. A large body of evidence has established that Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is the signaling receptor for LPS (8–10). Unlike most Toll-like receptors that bind their ligands directly, LPS binds a co-receptor MD-2 (11, 12), before interacting with TLR4. LPS binds to a hydrophobic pocket on MD-2, and initiates the dimerization of a TLR4/MD-2 dimer:dimer complex to initiate two distinct intracellular pathways: the MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways. The adaptor proteins, MyD88 and Mal, are subsequently recruited to TLR4, and have the primary role of activating the transcription factor NF-κB, which plays a critical role in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL6 (13–15). The MyD88-independent signaling pathway is activated by the recruitment of the adapters Trif and Tram, resulting in activation of interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and IRF7, which are critical for the expression of type I interferons (IFNs), including IFNβ (16, 17). It has been suggested that the subcellular localization of TLR4 plays a discriminatory role in activating the two signaling pathways (18, 19). Recognition of LPS on the cell surface activates the MyD88-dependent pathway (20), whereas recognition of LPS in the endosomes activates the MyD88-independent pathway (18).

Extensive interactions have been observed at the dimerization interface in the human TLR4/MD-2/LPS co-crystal structure (11), among which are hydrogen bonds as well as hydrophobic and ionic interactions (11). The role of hydrophobic interactions in receptor activation has been well documented by several mutagenesis studies (21, 22). Although we showed that ionic interactions and hydrogen bonds at the dimerization interface are essential for the species-specific activation of lipid IVa (23), the role of these interactions have not been unambiguously demonstrated for activation by lipid A. What is established is that both phosphates are required for the full-agonist activity of lipid A (24–26). Interestingly, monophosphoryl lipid A has been proposed to selectively favor the activation of the MyD88-independent (TRIF) pathway, and hence mediate the adjuvant activity of lipid A with minimal toxicity (27).

While the role of TLR4/MD-2 as an LPS receptor has been unequivocally established, alternative LPS receptors have been suggested to exist. Prior to the discovery of TLRs, numerous “LPS receptors” had been reported to exist (28–34). Indeed, although no functional evidence was reported, close examination of one of these “pre Toll receptor” papers suggests that the discovery of MD-2 as an LPS-binding protein might have pre dated the reports of Miyake et al (30). More recently, Haziot et. al reported that the lipid A component of E. coli LPS activated some proinflammatory responses in CD14- or TLR4-deficient mice that resulted in augmented bacterial clearance (35). Similarly, Miyake and coworkers demonstrated that LPS-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of CD19 was RP105-dependent but TLR4-independent (36). Furthermore, Schwartz and co workers reported that TLR4-independent signaling was activated when a TLR4-deficient murine macrophage cell line was incubated with B. fragilis LPS (37). It has also been reported that Neisseria meningitidis LPS is recognized independently from TLR4, MD-2 or CD14 in human meningeal cells (38).

To clarify the discrepancy and unambiguously identify any potential alternative LPS receptors, we carried out genome-wide microarray profiling of LPS responses in wild type, TLR4- and MD-2-deficient mouse macrophages. Synthetic lipid A was used for cell stimulations to exclude contaminants that could compromise data analysis. In addition, we used an LPS preparation that we had previously prepared that we knew to be free of lipoproteins and peptidoglycan (39). Under these conditions, we failed to unveil the existence of an alternative LPS receptor. With the knowledge that TLR4/MD-2 represent the only means that phagocytes have to respond to LPS, we re-focused our approach to characterizing TLR4. In order to determine the functional relevance of the intermolecular ionic interactions on lipid A activation, we assessed five positively charged residues on mouse TLR4: R264, K341, and K362 (Positive Patch 1), K367 and R434 (Positive Patch 2). We chose these residues because our computer model predicted that the two negatively charged phosphates on lipid IVa would coordinate with these residues in the active TLR4/MD-2/lipid IVa dimer:dimer (23). We found that when either positive patch was abolished by mutagenesis into Ala, the responses to lipid A or LPS were almost completely abrogated. However, the MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways were impaired to the same extent, indicating that decreased receptor activation, rather than selective pathway activation is likely to account for the adjuvant activity of monophosphorylated lipid A. Hence, we conclude that TLR4 and MD2 are absolutely required for the proinflammatory responses to E. coli LPS in mouse macrophages, and the optimal activation of the TLR4/MD-2 complex depends on the formation of intermolecular ionic interactions between TLR4, MD-2 and LPS.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Synthetic lipid IVa and lipid A were gifts of Dr. Shoichi Kusumoto (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). LPS from E. coli strain O111:B4 (Sigma) was re-purified by a repeat phenol-chloroform extraction (40). Pam2CSK4 (Pam2) were obtained from EMC Microcollection (Tubingen, Germany). C57BL/6 WT mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). TLR4-deficient and MD-2-deficient mice were gifts from S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) and K. Miyake (the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) respectively, and were subsequently backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background for over 6 generations.

Cell culture and stimulation

Bone marrows were harvested from the femurs and tibias of 6- to 8-week-old mice. Bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages were differentiated from bone marrow cells cultured in DMEM medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 20% L929-conditioned media and 10 µg/ml ciprofloxacin (Bayer, West Haven, CT). Ex vivo cultured macrophages were collected at day 8. Cell purity was analyzed by flow cytometry using CD11b-PerCPCy5.5 and F4/80-PE, and showed over 95% of double positive cells. The next day, cells were treated with 10 ng/ml lipoprotein- and peptidoglycan-free LPS, 100 ng/ml synthetic Lipid A or 10 nM Pam2CSK4 for 2 hours before RNA isolation.

RNA isolation and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed on RNA samples using SuperScript III-Two-Step qRT-PCR Kit with SYBR Green (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on the DNA engine opticon 2 cycler (MJ Research, Boston, MA). Gene expression data were normalized to b-actin expression and are presented as a ratio of gene copy number per 100 copies of b-actin. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for RT-PCR

| Forward (5’-3’) | Reverse (5’-3’) | |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TTGAACATGGCATTGTTACCAA | TGGCATAGAGGTCTTTACGGA |

| TNF-α | CAGTTCTATGGCCCAGACCCT | CGGACTCCGCAAAGTCTAAG |

| RANTES | GCCCACGTCAAGGAGTATTTCTA | ACACACTTGGCGGTTCCTTC |

| Abca2 | CCCGTCATGCAGTCGCTTT | CACTGGGTCGAACAAATTGCC |

| Adh5 | TGGTGAAGGGGTCACGAAG | ATGTGCTAGTCCCCATGAAGT |

TLR4−/− expression profile

Bone marrow cells from four C57BL/6 wide type, TLR4-deficient mice were pooled and cultured as described above. Total RNA was isolated from cells stimulated for 2 hours. RNA integrity was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). RNA was then labeled and hybridized to four individual arrays, swapping the Cy3 and Cy5 dyes as subsequently detailed. Eight mg RNA of both test and reference samples were reverse transcribed and differentially labeled with monoreactive Cy3 and Cy5 Dyes (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) using the Atlas Powerscript Fluorescent Labeling Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Labeled samples were purified with Cyscribe GFX Purification Kit (Amersham) and hybridized overnight using Genomic Solutions GeneTAC Hybridization Station (Perkin-Elmer, Boston, MA) to the PGA mouse v1.1 oligonucleotide array (Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Cambridge, MA). These arrays, including 19,549 reporters, were printed at the microarray core (MGH) using an Omnigrid printer (Genemachines Inc., San Carlos, CA) from 384-well polystyrene V-bottom plates (Genetix, Charlestown, MA) to Surmodics slides. Fluorescent images from the arrays were acquired using a microarray scanner and its accompanying software (GenePix 4000B microarray scanner; Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The gene expression profiles were compared with that of PBS-treated cells incubated for the same time. A comparison between wild type and TLR4-deficient PBS-treated cells was used to control for gene expression differences due to the genotype. The experiment was repeated once in its entirety, and yielded nearly identical results.

MD-2−/− expression profile

Bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 wild type or MD-2-deficient mice were cultured and treated as described above. Total RNA isolated from the cells was reverse transcribed, labeled and hybridized to 2 individual microarrays, swapping the Cy3 and Cy5 dyes. Cells from 2 individual mice of each genotype were used, and each mouse served as its own PBS-treated control. Control comparisons between wild type and MD-2-deficient PBS-treated cells were also performed. RNA quality was assessed as described above. Microarrays were produced at the Swegene DNA Microarray Resource Center, Department of Oncology, Lund University, Sweden (http://swegene.onk.lu.se). Mouse array-ready oligonucleotide libraries Version 4.0, comprising 35,852 unique probes, were obtained from Operon (Operon Biotechnologies, Germany). Probes were printed on aminosilane coated glass slides (UltraGAPS, Corning) using a MicroGrid2 robot (BioRobotics, Cambridgeshire, UK) equipped with MicroSpot 10K pins (BioRobotics). Fluorescence-labeled cRNA target was prepared from 500 ng total RNA using Agilent Low Linear amplification kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Pretreatment of arrays, hybridization, and post-hybridization washes was carried out according to manufacturers’ instructions (Corning ChipShot™ labeling system). Hybridized microarrays were imaged using an Agilent G2565AA microarray scanner (Agilent Technologies). Fluorescence intensities were extracted using Gene Pix Pro 4.0 software (Axon Instruments Inc., Foster City, CA).

Microarray analysis

All microarray data were stored, filtered and normalized in the BioArray Software Environment (BASE; http://base.thep.lu.se/) (41). T test statistics with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing were calculated in the R software environment for statistical computing (http://www.r-project.org/). Hierarchical and K-means clustering analysis was performed using the MultiExperiment Viewer software (http://www.tm4.org/) (42). Self-organizing map clustering was performed with Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector v.2.1 (GEDI; http://web1.tch.harvard.edu/research/ingber/GEDI/gedihome.htm) (43). Gene ontology analysis was preformed with the Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer v2.0 software (EASE; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/ease/ease.jsp) (44). Microarray data have been deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus with the SuperSeries accession number GSE31078 for both TLR4 and MD-2 deficient expression profiles (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

ELISA

BM-derived macrophages (day 7) were plated and cultured in 96-well plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as 5×104 per well for 1 day prior to the treatment. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 16h after the stimulation and analyzed for the presence of TNF-a and RANTES by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Mutagenesis

All mutants were created by site-directed mutagenesis according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QuikChange). The two mutants, R264A_K341A_K362A and R264A_K341A_K362A_E369K_Q436R were created from wild type human TLR4 construct on a PCDNA3 vector (23). The two other mutants, K263A_R337A_K360A and K263A_R337A_K360A_K367A_R434A were created from wild type mouse TLR4 construct on a PCDNA3 vector. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing (Genewiz, Inc., South Plainfield, NJ).

Luciferase assay

The effects of these mutations on LPS, lipid A and lipid IVa signaling were tested in HEK293 cells by transient transfection using the transfection reagent GeneJuice (Invitrogen). HEK293 cells were plated in 96 well plates at a density of 20,000 cells/well. The next day, cells were transfected with: 1) one of the TLR4 constructs (1 ng/well), 2) wild type hMD-2 or mMD-2 construct (100 ng/well), 3) an NF-κB-luciferase or interferon (IFN) β-luciferase plasmid (40 ng/well) (45), and 4) the renilla-luciferase plasmid (40 ng/well). After 8–10 h of transfection, cells were stimulated with indicated concentrations of lipid A/LPS/lipid IVa. Luciferase activities were determined in cell lysates 10–12 h later. Renilla-luciferase was used to normalize for NF-κB-luciferase or IFNβ-luciferase.

Immunoprecipitation and immuno blotting analysis

HEK293T cells were plated on 6 well plates at a density of 500,000 cells/well. The next day, cells were transfected with 1 µg of TLR4 mutant and 1 µg of MD-2 wild type constructs per well using GeneJuice. After two days, supernatants were removed, and cells were lysed with 350 µl lysis buffer (1% trition X-100 in PBS). Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C on a tabletop centrifuge. Clear cell lysates were either subject to SDS-PAGE for direct immune blotting (IB)/western blotting (WB) analysis, or immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by IB/WB analysis.

4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels were used for IB. Prestained rainbow marker (GE) and Kaleidoscope marker (Bio-rad) were loaded onto the same gel as the samples for molecular weight estimation. After electrophoresis, the gels were transferred to Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences) and blocked in blocking buffer (10% milk in PBS) for 1 h. The blots were then separated into three pieces at the approximate molecular weights of 80 KD and 38 KD according to the prestained molecular weight markers. The top blots (MW≥80 KD) were blotted against anti-GFP monoclonal Ab (mAb) (Invitrogen) for detection of YFP-tagged TLR4 proteins, the middle blots (38 KD≤MW≤80 KD) were blotted against anti-β-actin mAb (Sigma) for detection of β-actin, and the bottom blots (MW≤38 KD) were blotted against penta-his mAb (Qiagen) for detection of His6-tagged MD-2 proteins. Anti-mouse secondary Ab (Bio-rad) and standard developing procedures were used for detections of perspective proteins.

For immunoprecipitation (IP) with Ni-NTA agarose beads, 700 µl clear cell lysates (for each mutant) pooled from 2 wells on 6 well plates were incubated with 40 µl of Ni-NTA agarose beads at 4°C overnight with constant shaking. Supernatants were then removed, and beads were washed three times with Ni-NTA wash buffer (20 mM Imidazole, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM KCl, 10% Glycerol). Twenty ul of elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 100 mM KCl, 100 mM Imidazole, 10 % Glycerol) were added to the beads to elute His-tagged proteins. The eluates were then subject to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis. After blocking with 10% milk solution, the membranes were cut into two pieces at the molecular weight of ~ 60 kD according to prestained molecular weight marker. The upper blots were blotted against anti-GFP monoclonal Ab (mAb) for detection of YFP-tagged TLR4 proteins, and the lower blots were blotted against penta-his mAb for detection of His6-tagged MD-2 proteins.

For IP with anti-GFP pAb, 700 µl clear cell lysates from each mutant were incubated with 2 µg of anti-GFP polyclonal Ab (Invitrogen) and 20 ml of protein A activated sepharose beads (Thermo Scientific) overnight at 4 °C. Supernatants were then removed, pellets were washed three times with PBST buffer (0.05% Tween in PBS), and subject to SDS-PAGE and IB analysis. After blocking in 10% milk solution, the nitrocellulose membranes were cut into two pieces at the molecular weight of ~ 60 kD. The upper blots were blotted against anti-GFP mAb for detection of YFP-tagged TLR4 proteins, and the lower blots were blotted against penta-his mAb for detection of His6-tagged MD-2 proteins.

Two wells of clear cell lysates (350 µl/well) from each mutant were pooled, and incubated with 3 µg of biotinylated LPS (Invivogen) and 20 µl of streptadvidin agarose resin (Thermo Scientific) at 4 °C with constant shaking for the affinity precipitation experiments using biotinylated LPS. The next day, supernatants were removed, the pellets were washed three times with PBST buffer (0.05% Tween in PBS), and then subject to SDS-PAGE and western blotting analysis. Prestained rainbow marker (GE) and Kaleidoscope marker (Bio-rad) were loaded into the same gel for molecular weight estimation. After blocked with blocking buffer for 1 h, the nitrocellulose membranes were cut into two pieces at the molecular weight of ~ 60 kD. The upper blots were blotted against anti-GFP mAb for detection of YFP-tagged TLR4 proteins, and the lower blots were blotted against penta-his mAb for detection of His6-tagged MD-2 proteins.

Results

Microarray analysis of the role of TLR4 in LPS signaling

We first assessed the absolute requirement of TLR4 in LPS signaling by using TLR4-deficient BM-derived macrophages (BMDM). Synthetic lipid A or ultrapure LPS went through a second phenol-chlorform extraction, peptidoglycan digestion with mutanolysin and gel filtration chromatography were used as the stimulants to avoid stimulatory effects from potential contaminants. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type C57Bl/6 and the TLR2 ligand, Pam2, were used as controls. TNFa and RANTES productions, which respectively represent the activations of MyD88-dependent and –independent pathways, were assayed at the protein level by ELISA, or at the RNA level by quantitative PCR.

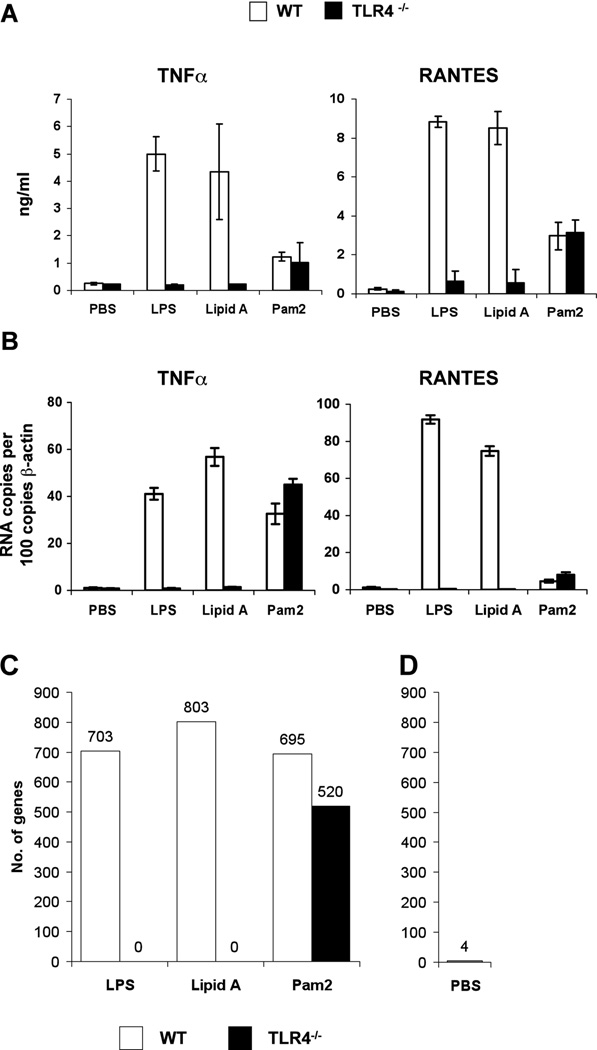

Compared to wild type (WT) BMDM, TLR4-deficient BMDM did not respond to LPS or lipid A stimulation, whether judged by TNFa production, as an example of a gene product that is dependent on the MyD88-dependent signaling pathway, or RANTES production as an example of the MyD88-independent signaling pathway (Fig. 1A). This suggested that TLR4 is required for the canonical LPS response. The fact that the TLR4-deficient BMDM responded normally to PAM2 stimulation indicates that the defect in TLR4, accounted for the lack of inflammatory responses to LPS or synthetic lipid A.

Figure 1. The induction of LPS-responsive genes is dependent on TLR4 signaling.

BMDMs from wild type or TLR4−/− mice were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS, 100 ng/ml Lipid A, 10 mM Pam2 or PBS control. TNFa and RANTES protein level was measured in the supernatant by ELISA after 16h of stimulation (A). TNFa and RANTES RNA level was measured in the cells by qPCR after 2h of stimulation (B). Data shown in (A, B) are one representative figure for 3 repeating experiments. The number of genes that are significantly induced or repressed by LPS, lipid A and Pam2 in wild type or TLR4−/− macrophages is shown in (C), and the number of genes with altered basal expression between wild type and TLR4−/− macrophages is shown in (D).

To examine the existence of any “non-canonical” LPS signaling pathway, we did microarray RNA profiling in WT and TLR4-deficient BMDMs. We chose 2 h of stimulations for RNA profiling because, at this time point, the mRNA expression of TNFa and RANTES were consistent with the ELISA results (Fig. 1B). RNA was extracted after 2 h treatment with 10 ng/ml LPS, 100 ng/ml lipid A, 10 nM PAM2, or PBS. A response was defined as any gene that was induced or repressed more than 1.6 fold over PBS control with a statistical significant difference (fold change > 1.6 and P < 0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing). With this approach, a set of 1,396 genes was selected and analyzed in more detail. About equal numbers of genes (~700–800 genes) were responsive to each ligand in the WT macrophages (Fig. 1C). In contrast, not a single gene was found responsive to lipid A or LPS in the TLR4-deficient BMDM, whereas the PAM2 response was largely preserved in these cells (Fig. 1C). The lack of genes induced by either LPS or lipid A in TLR4-deficient macrophages in this genome wide expression analysis show that TLR4 is absolutely required for the initiation of an LPS response.

A comparison of the PBS-treated WT and TLR4-deficient macrophages revealed that only four genes had significantly different basal levels of expression (Fig. 1D). These genes were CD274 antigen (PD-L1), occludin/ELL domain containing 1, proteasome 26S subunit non-ATPase 4, and RIKEN cDNA 9130017C17 of unknown function. However, at the chosen significance level (p<0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg correction), about 70 genes would still be expected to be false positives, even after multiple testing corrections (at p<0.05, 5% of 1,396 genes may still be false positives). In fact, we subsequently tested LPS-induced gene expression of these four genes by RT-PCR and failed to induce message, confirming that these were, in fact, false positives.

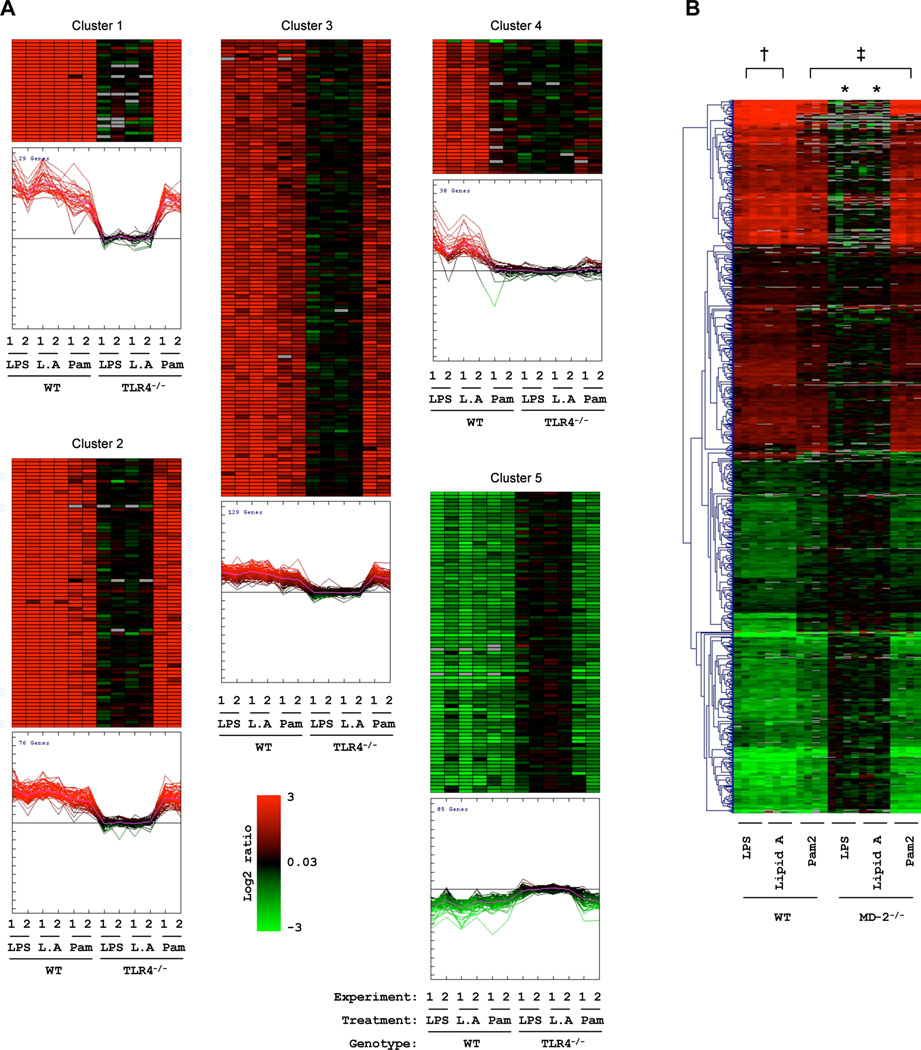

We next set out to group the set of 1,396 responsive genes based on their expression profile. Five main gene clusters containing the most induced and repressed genes emerged by hierarchical and K-means clustering analysis (Fig. 2A). In Cluster 1, 29 genes were highly induced by all treatments in WT cells with expression increasing more than 30 fold upon LPS or Lipid A treatment. Cluster 2 includes moderately LPS induced genes (about 8–30 fold) and Cluster 3 includes slightly LPS induced genes (about 2–8 fold). The expression profile of Cluster 1–3 was similar and group association was dictated by the level of induction. In contrast, Cluster 4 displayed a different profile and contained genes induced by LPS and lipid A treatment but not Pam2 stimulation. Cluster 5 includes LPS-repressed genes.

Figure 2. Cluster analysis of TLR4 and MD-2 dependency.

Five clusters of TLR4-dependent genes were sorted out by hierarchical and K-means cluster analysis based on the gene expression profile in response to LPS, lipid A or Pam2 (A). Cluster 1–3 contains genes induced by all three treatments in WT cells to different degrees. Cluster 4 contains genes induced by LPS and lipid A, but not by Pam2. The genes repressed by LPS stimulation were grouped together in Cluster 5. Gene expression in response to LPS, lipid A or Pam2 stimulation in WT and MD-2−/− macrophages was visualized by hierarchical clustering analysis in (B). The symbol * indicates that no genes were significantly induced or repressed in MD-2−/− macrophages after stimulation with LPS or lipid A. The symbol † indicates that no genes were significantly different between LPS- and Lipid A-stimulated WT cells. The symbol ‡ indicates that no genes were significantly different between WT and MD-2−/− cells after Pam2 stimulation.

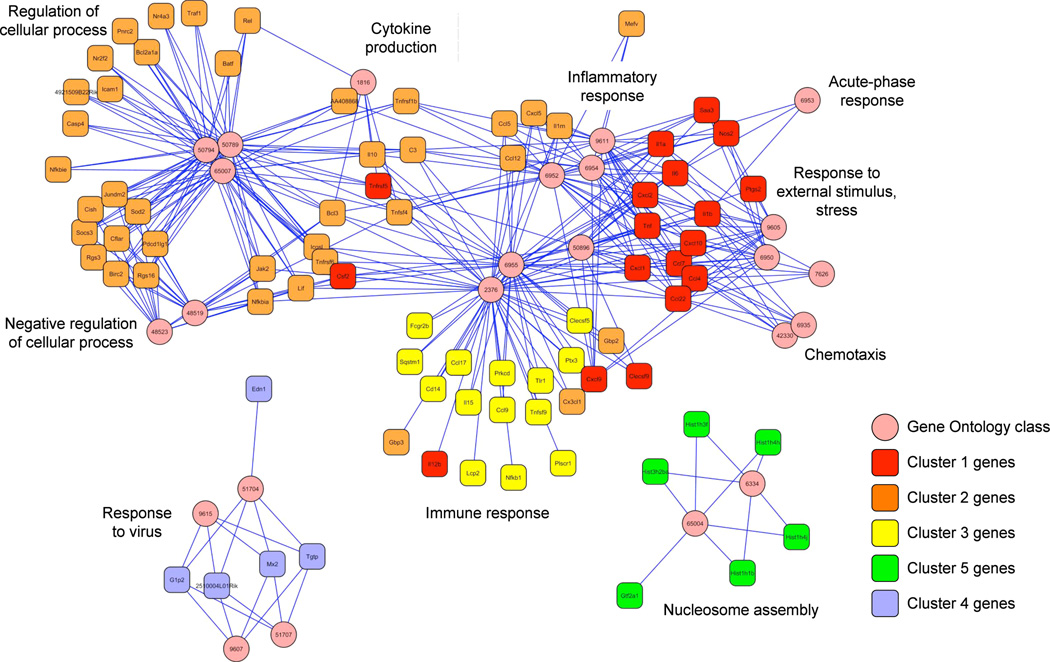

To investigate if the grouping of genes into five main clusters also reflected differences in function between these groups, we analyzed the gene ontology (GO) definitions assigned to these genes. Statistically over represented GO definitions (in comparison to a random selection) were identified with the EASE software (Table 2). To visualize how genes mapped to different GO definitions, we created a network with the Cytoscape software (Fig. 3). Interestingly, genes from Cluster 1–3 mapped to a continuous network, whereas Cluster 4 and 5 were segregated to separate networks. Thus, Cluster 1–3 with similar expression profiles also contains genes with similar functions, whereas Cluster 4 and 5 may contain genes with separate biological function. Interestingly, Cluster 4 contains many interferon-regulated genes with a significant over representation of genes with the GO definition “response to virus”. This may indicate that the gene programs in response to LPS but not Pam2 are also important for viral host defenses, consistent with the presence of many interferon regulated genes. The genes down regulated by LPS found in Cluster 5 are associated with protein-DNA complex assembly genes such as histones. Perhaps down regulation of these genes is required to allow the massive inflammatory gene program to be mobilized in response to a pathogen insult. Even if the Cluster 1–3 maps to a continuous functional network in Figure 3, some preferences exist. Cluster 1 includes classical inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1β etc. In contrast, Cluster 2 includes immune response genes with attributed functions in regulation of biological processes. Cluster 3 includes many well known immune response genes, but no further clues that a common function could be obtained from the over representation of gene ontology definitions.

Table 2.

Gene ontology analysis of LPS-responsive macrophage gene clusters.

| Accession | Definition | No. of genes† |

Corrected P value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly LPS induced genes (Cluster 1, 29 genes) | |||

| Including Tnf, Il1a, Il1b, Nos2, Ptgs2, Il6, Saa3, Cxcl10, Cxcl2, Ccl4, Ccl7 | |||

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 14 of 184 | 1.52E-14 |

| GO:0006955 | Immune response | 15 of 335 | 9.98E-13 |

| GO:0006935 | Chemotaxis | 6 of 93 | 0.00094 |

| GO:0006953 | Acute-phase response | 4 of 26 | 0.012 |

| GO:0005125 | Cytokine activity | 13 of 187 | 1.23E-13 |

| GO:0008009 | Chemokine activity | 7 of 34 | 8.6E-09 |

| GO:0042379 | Chemokine receptor binding | 7 of 34 | 8.6E-09 |

| GO:0008083 | Growth factor activity | 5 of 137 | 0.024 |

| Moderately LPS induced genes (Cluster 2, 76 genes) | |||

| Including Icam1, Nfkbie, Traf1, Rel, Icosl, Jak2, Nfkbia, Il10, Socs3, Jundm2 | |||

| GO:0006955 | Immune response | 17 of 335 | 8.89E-09 |

| GO:0050794 | Regulation of cellular process | 33 of 2457 | 0.000057 |

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 10 of 184 | 0.00034 |

| GO:0048523 | Negative regulation of cellular process | 15 of 704 | 0.010 |

| GO:0001816 | Cytokine production | 6 of 82 | 0.046 |

| GO:0005125 | Cytokine activity | 10 of 187 | 0.000075 |

| GO:0008009 | Chemokine activity | 5 of 34 | 0.0040 |

| GO:0042379 | Chemokine receptor binding | 5 of 34 | 0.0040 |

| Slightly LPS induced genes (Cluster 3, 115 genes) | |||

| Including Tlr1, Cd14, Fcgr2b, Ccl9, Ccl17, Il15 | |||

| GO:0006955 | Immune response | 13 of 335 | 0.012 |

| LPS, but not Pam2, induced genes (Cluster 4, 24 genes) | |||

| Including Mx2, G1p2,Tgtp | |||

| GO:0009615 | Response to virus | 5 of 37 | 0.000081 |

| GO:0017111 | Nucleoside-triphosphatase activity | 7 of 386 | 0.0024 |

| GO:0003924 | GTPase activity | 5 of 118 | 0.0034 |

| LPS repressed genes (Cluster 5, 125 genes) | |||

| Including Hist1h1b, Hist1h4h, Hist3h2ba | |||

| GO:0065004 | Protein-DNA complex assembly | 7 of 71 | 0.024 |

| GO:0006334 | Nucleosome assembly | 6 of 48 | 0.041 |

Number of genes found in the cluster out of the total number of genes with this annotation.

P value for over-representation of GO accession in the cluster compared to randomly selecting an equal number of genes. Bonferroni corrected for multiple testing.

Figure 3. A functional network of the LPS response.

The statistical over-representation of GO definitions in cluster 1–5 from Figure 2A was analyzed by the EASE software (see Table 2). Genes (boxes) were mapped to GO definitions (circles) and visualized with the Cytoscape software.

Microarray analysis of the role of MD-2 in LPS signaling

The canonical LPS signaling pathway through TLR4 depends on the co-receptor MD-2 (11, 12, 46). In order to test if MD-2 is absolutely required for any LPS response in analogy with TLR4, we determined the gene expression profile of wild-type and MD-2-deficient BMDMs after 2 h of stimulations with 10 ng/ml LPS, 100 ng/ml lipid A, 10̣ nM Pam2, or PBS control. Basal gene expression was compared between PBS-stimulated WT and MD-2-deficient BMDMs. No genes were found to be significantly different in the PBS-treated WT vs. MD-2-deficient macrophages.

In WT BMDMs, 912 genes were significantly induced or repressed (fold change ≠ 1; P < 0.05) after stimulations with LPS, lipid A or Pam2 (Fig. 2B). However, in the MD-2-deficient BMDMs, not a single gene was found to be significantly stimulated by LPS or lipid A, showing that MD-2 expression is absolutely necessary for the induction of a LPS response. In comparison, the gene expression profile for Pam2 stimulation remained the same for WT and MD-2-deficient BMDMs, confirming that MD-2 is indeed required for LPS signaling. Noticeably, similar genes were activated by LPS and lipid A in WT BMDM, indicating that indeed, lipid A is the active component in LPS in triggering the proinflammatory responses.

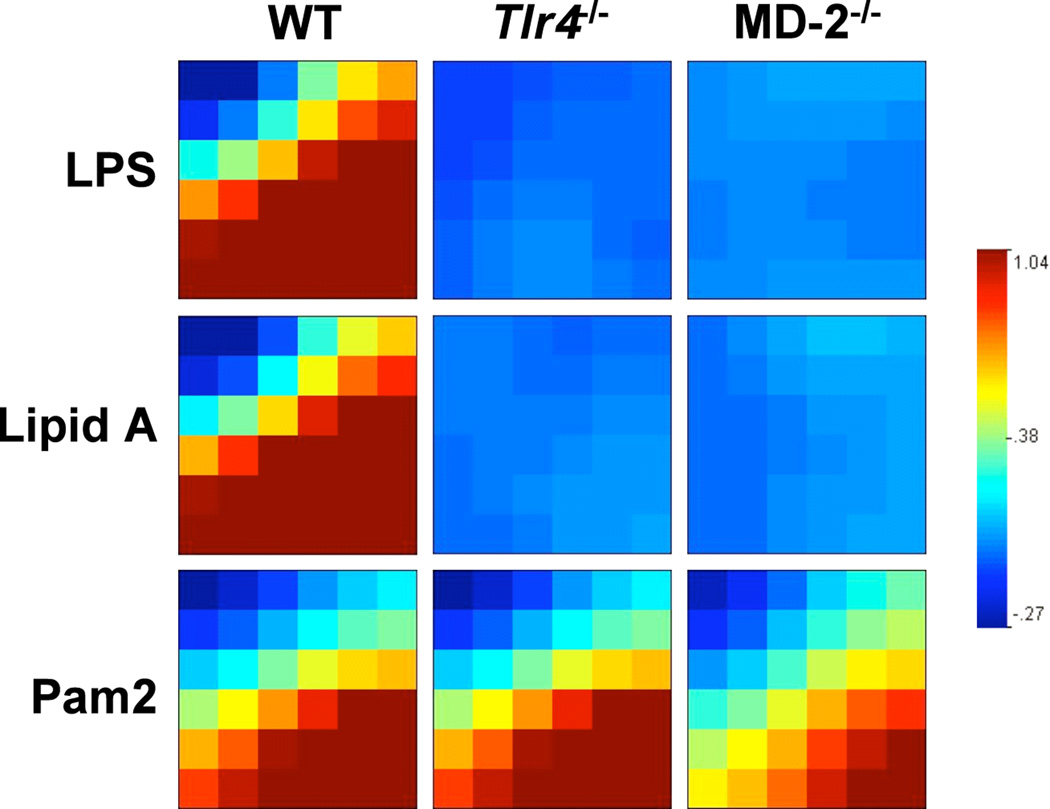

To compare the microarray experiments done in TLR4- and MD-2-deficient BMDMs, we first identified genes present on both microarray platforms (6013genes) by ensuring the reporter sequences aligned to the same target sequence using the BLAST algorithm. We found 361 genes to be induced or repressed >1.3 fold by LPS in the WT BMDMs of each experiment. A mosaic map was generated for each stimulant of each genotype by the GEDI software that clusters genes with a self-organizing map (SOM) algorithm (Fig. 4). This analysis shows that the global expression profile induced by LPS and lipid A is very similar and absolutely dependent on both TLR4 and MD-2, whereas the global expression profile induced by Pam2 is largely unaltered by the absence of TLR4 and MD-2.

Figure 4. The gene responses to LPS, lipid A or Pam2 are very similar in TLR4−/− and MD-2−/− BMDM in the two microarray experiments.

A GEDI graphical mosaic of the global expression profile of 361 LPS-responsive genes (induced or repressed > 1.3 fold in the WT mice of each experiment) illustrates the absolute requirement of TLR4 and MD-2 in the LPS response and the similarity of gene responses in the two microarray experiments performed on different microarray platforms.

The two phosphates on lipid IVa are in close proximity with two positively charged patches on mTLR4 in an mTLR4/mMD-2/ lipid IVa model

In view of the absolute need to engage TLR4/MD-2 in responding to LPS, we set out to determine the mechanistic details of receptor activation. Our analysis was designed to take into account both of these essential receptor components and was consistent with the hypothesis, first enunciated by our group in 1990, that by defining the details of the receptor that engages and responds to the lipid A precursor known as lipid IVa, we would simultaneously define how LPS functions.

Our previous studies have suggested that ionic inter-molecular actions between positively charged residues on TLR4/MD-2 and lipid IVa are likely to be critical elements in the activation of TLR4/MD-2. Thus, we more closely examined the role of ionic interactions in TLR4 activation. We had previously shown that ionic interactions at the dimerization interface are essential for the species-specific activation of lipid IVa (23, 47). In our current analysis, we set out to define the role of ionic interactions in lipid A/LPS activation.

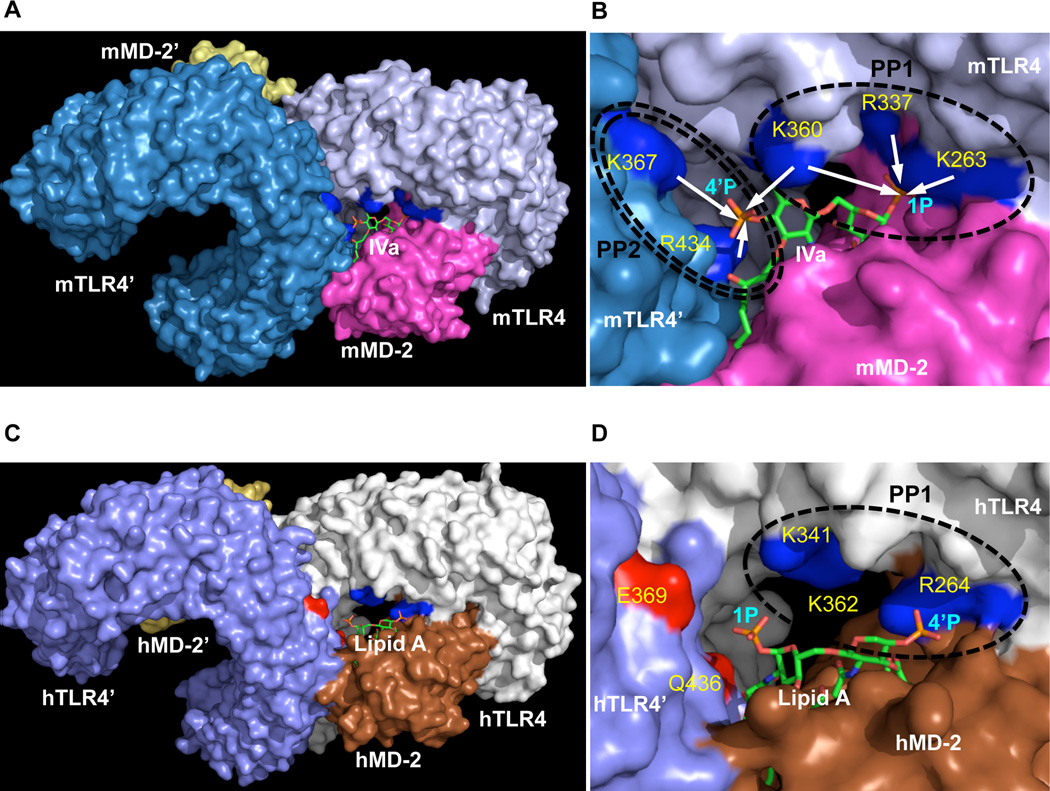

Two sets of ionic interactions were observed between the two phosphates of lipid IVa and two patches of positive charges on mouse TLR4 (mTLR4) in our dimeric mTLR4/mMD-2/lipid IVa model (Fig. 5 A–B). One is between the 1-PO3 and K263, R337, K360 (Positive Patch 1) on mouse TLR4 within the same TLR4-MD-2-LPS complex, and the other is between the 4’-PO3 and K367 and R434 (Positive Patch 2) at the dimerization interface. To examine the functional relevance of these ionic interactions on the general lipid A/LPS response, we mutated these positively charged residues to alanine, and examined their effects by reporter-driven luciferase assay and co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP).

Figure 5. Ionic interactions at the two patches in the dimeric TLR4/MD-2/lipid IVa(A) complex.

A dimeric mTLR4/mMD-2/lipid IVa model (23) is shown in A & B, and a dimeric hTLR4/hMD-2/lipid A crystal structure (11) is shown in C & D. Zoomed-in views of the two positive patches are shown in B & D. TLR4 and MD-2 are shown in surface view, and lipid IVa and lipid A are shown in stick view. Blue stands for the Positive Patches on both human and mouse TLR4, and red stands for the two negatively charged surface on human TLR4. Positive Patch 1 (PP1) and Positive Patch 2 (PP2) are labeled by single and double circles respectively in B & D. The symbol ’ indicates TLR4 and MD-2 molecules from the second complex. White arrows in B indicate predicted ionic interactions between the positively charged residues on mTLR4 and the two negatively charged phosphates on lipid IVa. Molecules as colored and labeled in the Figure. The graphics were created in PyMol (Delano Scientific).

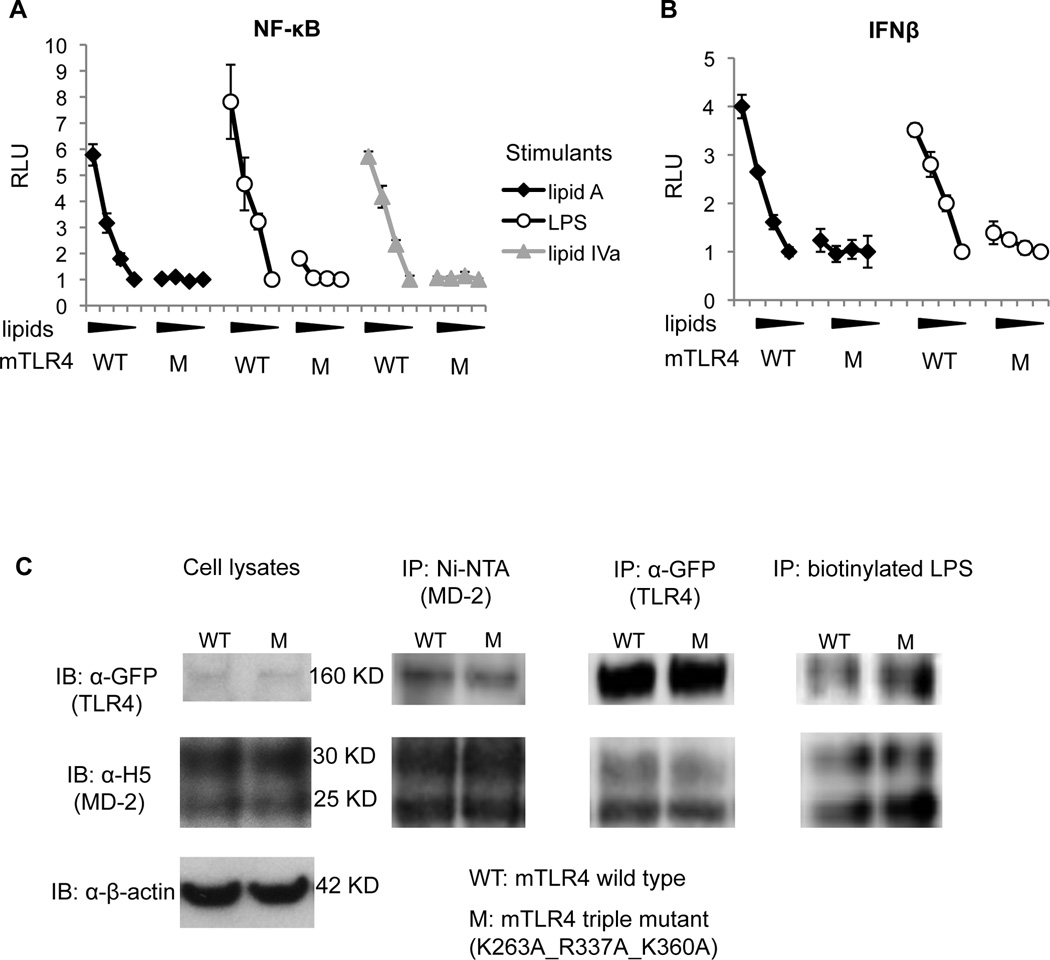

A mouse TLR4 triple mutant in which K263, R337, and K360 were replaced with alanine, is strikingly impaired in the lipid A responsiveness

We first examined the triple mutations of K263A, R337A and K360A on lipid A/LPS responsiveness. As shown in Fig. 6A, when these three positively charged residues were mutated to alanine simultaneously, NF-κB activations by lipid A, LPS, or lipid IVa were significantly impaired, indicating that ionic interactions between K263, R337, and K360 and the phosphates on lipid A are essential for the activation of the MyD88-dependent pathway by these ligands. Similarly, IFNβ activations by lipid A and LPS were almost abrogated after these mutations (Fig. 6B), indicating that ionic interactions with these residues are also required for the MyD88-independent pathway. As shown in Fig. 6C, protein expression (Cell lysates) and mouse MD-2 (mMD-2) binding activity (IP: Ni-NTA, IP: α-GFP) were not affected by these mutations. In addition, the LPS binding activity of the mTLR4/mMD-2 complex was not affected by these mutations (IP: biotinylated LPS). Thus, the loss of function after the triple mutations results from impaired function, but not from disrupted protein expression or folding that would impair LPS binding.

Figure 6. Ionic interactions between K263, R337, and K360 on mTLR4 and the two phosphates on lipid A/LPS are essential for LPS signaling.

HEK293T cells were transfected with mMD-2, WT or the mutant K263A_R337A_K360A (M) mTLR4 constructs, and reporter constructs. After overnight transfection, cells were stimulated with 1000, 100, 10, 0 ng/ml of lipid A, LPS, or lipid IVa. The next day, supernatants were removed, and NF-κB-luciferase (A) or IFNβ-luciferase (B) activities were measured in cell lysates. Relative luciferase unit (RLU) has been normalized by renilla-luciferase. For western blots in (C), HEK293T cells were transfected with WT/M mTLR4 (1 µg/well) and wild type mMD-2 construct (1 µg/well). After 48 hs of transfection, clear cell lysates were subject to SDS-PAGE for direct IB (Cell lysates in C) with anti-GFP monoclonal Ab to detect hTLR4, Penta-his Ab to detect hMD-2, anti-β-actin Ab to detect β-actin. Clear cell lysates were also subject to IP with Ni-NTA agarose and IB (IP: Ni-NTA in C), IP with anti-GFP/protein A sepharose and IB (IP: α-GFP in C), and IP with biotynylated LPS/streptadvin sepharose and IB (IP: biotinylated LPS in C). Polyclonal α-GFP Ab was used for IP, and monoclonal α-GFP Ab was used for IB. Data shown are one representative figure of four repeating experiments.

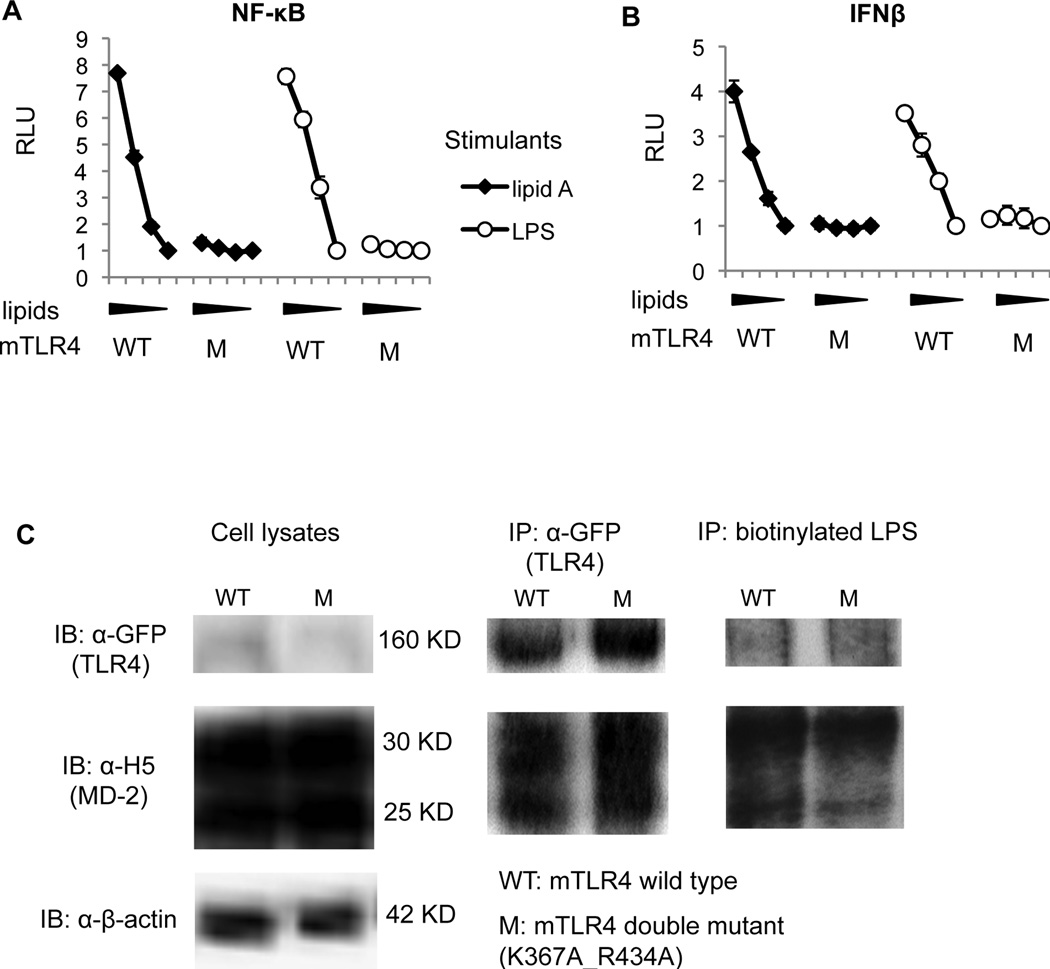

Positively charged K367 and R434 at the dimerization interface are also required for mouse TLR4 activation

Using charge reversal mutagenesis, we have previously shown that ionic interactions between K367 and R434 on mTLR4 and the phosphate on lipid IVa at the dimerization interface are essential for the species-specific activation of lipid IVa (23, 47). To assess the role of this set of ionic interactions on the general lipid A response, we mutated K367 and R434 into alanine, and examined the effect by inducible luciferase assay and co-IP.

As shown in Fig. 7A, NF-κB activations were greatly reduced by lipid A and LPS after the K367A and R434A mutations; similarly, IFNβ activations were significantly impaired after the combined mutations (Fig. 7B). Meanwhile, protein expressions and MD-2/LPS binding ability were not affected by these mutations (Fig. 7C). Thus, the loss of function after the charge abolishment at Positive Patch 2 arises from impaired activation rather than impaired protein folding or MD-2/LPS binding.

Figure 7. Ionic interactions between K367 and R434 on mTLR4 and the two phosphates on lipid A/LPS are essential for LPS signaling.

Luciferase assay (A&B) and western blots (C) were performed as described above except that mTLR4 WT/the K367A_R434A mutant (M) were transfected. NF-κB-luciferase activity is shown in (A), and IFNβ-luciferase activity is shown in (B). The luciferase shown (RLU) has been normalized by renilla-luciferase. Data are one representative figure of four repeating experiments.

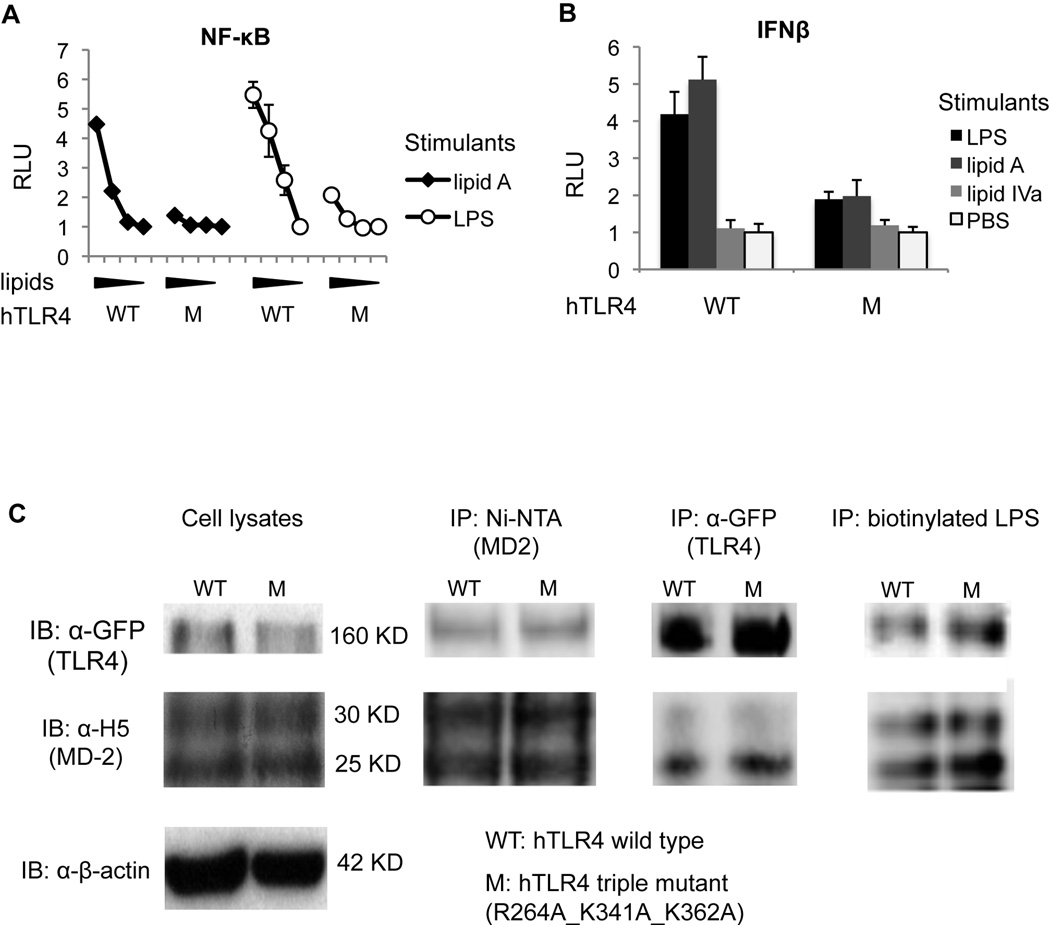

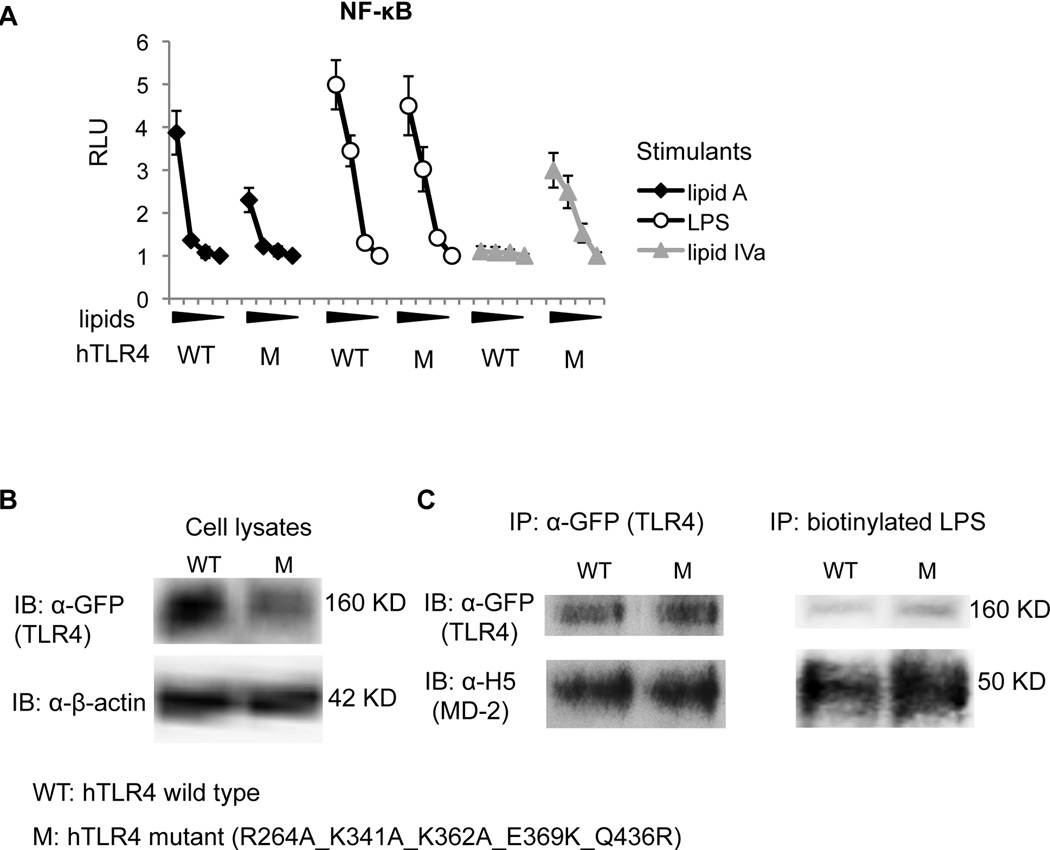

Human TLR4 loses its LPS response when the three positively charged residues, R264, K341, and K362, are simultaneously changed to Ala

A similarly positively charged patch was observed when we reviewed the crystal structure of human TLR4 (21). Human TLR4 interacts extensively with the negatively charged phosphates on the lipid A portion of LPS in the co-crystal structure (Fig. 5 C–D). To address the physiological role of these positively charged residues in the activation of the human TLR4/MD-2 receptor, we generated the triple mutant, R264A_K341A_K362A, and assessed its effect by inducible luciferase activity and co-IP.

As shown in Fig. 8A, NF-κB activation was significantly impaired in TLR4 that had the combined mutations of R264A, K341A, and K362A. Similarly, the IFNβ-inducible activity was greatly reduced after these mutations (Fig. 8B). This diminished response was not due to diminished receptor expression due to the triple mutations (Fig. 8C). These results suggest that ionic interactions between the positively charged residues on TLR4 in Positive Patch 1 and the two phosphates on lipid A/LPS are essential for both MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways of TLR4 activation.

Figure 8. Ionic interactions between R264, K341, and K362 on hTLR4 and the two phosphates on lipid A/LPS are essential for LPS signaling.

HEK293T cells were transfected with hMD-2, hTLR4 WT or the mutant R264A_K341A_K362A (M) construct, and reporter constructs. NF-κB-luciferase was measured after stimulations with 1000, 100, 10, 0 ng/ml of lipid A, or LPS in (A). IFNβ-luciferase was measured after stimulations with 1000 ng/ml of LPS, lipid A, or lipid IVa in (B). Relative luciferase unit (RLU) has been normalized by renilla-luciferase. Western blotting (C) was performed similarly as in Fig. 6 except that hMD-2 WT and hTLR4 WT or the R264A_K341A_K362A mutant were transfected. Data are one representative figure of four repeating experiments.

Charge reversal at the dimerization interface conferred LPS responses to the human TLR4 R264A_K341A_K362A mutant

Unlike mouse TLR4, with its two positively charged residues at the dimerization interface (K367 and R434; Fig. 5B), human TLR4 has two negatively charged residues at these locations (E369 and Q436; Fig. 5D). We have shown that the charge differences here are responsible for the role of TLR4 in the species-specific activation of lipid IVa (23, 47). We thus examined the effect of charge reversal at the dimerization interface on human TLR4 activation in the presence of the R264A_K341A_K362A mutations. Purified monomeric mouse MD-2 protein was used to complement transfected human TLR4 because mouse MD-2 and human TLR4 will not form a functional receptor when co-transfected in HEK293 cells due to the extremely poor expression of mouse MD-2 under these circumstances.

Interestingly, the quintuple mutant retained a partial lipid A response, retained complete responses to LPS, and acquired a response to lipid IVa (Fig. 9A). Again, protein expression (Fig. 9B) and MD-2/LPS binding (Fig. 9C) were not affected by these mutations. This indicates that gain of ionic interactions at Positive Patch 2 outweighs the loss of ionic interactions at Positive Patch 1 for the hTLR4/mMD-2 combination in regard to LPS responsiveness, whereas ionic interactions at positive patch 1 are required for a full response to lipid A.

Figure 9. Human TLR4 gained lipid IVa responsiveness after combined mutagenesis of charge reversal at the dimerization interface and charge removal at Positive Patch 1.

HEK293 cells were transfected with hTLR4 WT or the mutant R264A_K341A_K362A_E369K_Q436R (M) construct and reporter constructs. The next day, 200 ng/ml of monomeric mMD-2 were added to the culture. Cells were then stimulated with 1000 ng/ml, 100 ng/ml, 10 ng/ml, or 0 ng/ml of lipid A, LPS, or lipid IVa for luciferase assay (A) the next day. For western blot analysis, HEK293 cells were transfected with hTLR4 WT or the mutant (R263A_K341A_K362A_E369K_Q436R) construct only. Clear cell lysates were subject to SDS-PAGE for direct WB analysis (B), or incubated with soluble monomeric mMD-2 proteins (2 µg/well) for co-IP with anti-GFP polyclonal Ab and IB), or co-IP with biotynylated LPS/streptadvin sepharose beads and IB (C). Data are one representative figure of four repeating experiments.

Discussions

The initiation of host defenses against Gram-negative bacterial invasion are primarily dependent upon LPS recognition by TLR4/MD-2. However, the presence of an alternative LPS receptor was suggested by different studies from different groups (31–33, 35, 37, 38, 48, 49), and it remained an unanswered question whether alternative means of recognizing LPS existed, especially for so-called non-cannonical responses. To examine this possibility, with the hopes of identifying “the alternative LPS receptor”, we carried out an unbiased genome-wide screen of the mRNA transcription profile in mouse macrophages after 2 h of LPS stimulation (48). Under these conditions, we found that the TLR4/MD-2 receptor complex was absolutely required for E. coli LPS signaling. While we cannot exclude the possibility that LPS-induced TLR4/MD-2 independent signaling might be detectable beyond the 2 h time point, or in another cell type, or at higher LPS doses, it appears likely that mammals lack any additional receptor systems to respond to LPS.

These experiments also help in determining the role of MD-2 in the response to bacterial lipoprotein, an important alternative means of Gram-negative recognition after the LPS response, and an important means the innate immune system utilizes for detecting Gram-positive bacteria. MD-2 has been reported to play a role in TLR2-mediated responses of lipoproteins (50). However, in our screen, the control Pam2 stimulation failed to initiate a differential expression profile in WT and MD-2-deficient macrophages. As such, our screen suggests that Pam2-initiated TLR2 signaling is completely independent of MD-2.

Upon ligand recognition, TLR4 activates both the MyD88-dependent and –independent pathways, whereas TLR2 activates only the MyD88-dependent pathway. In accordance with this observation, we found that 38 genes were activated by LPS but not by Pam2 (Cluster 4, Fig. 2A). At least 10 genes in this cluster are IFN-related genes. Moreover, several Pam2-induced genes, e.g., Irg1, Icos1, Traf1 and Mlp, were MyD88-independent when LPS was used as the stimulating ligand (48). This suggests that the adaptor functions of MyD88/MAL are not identical for TLR2 vs. TLR4 signaling.

LPS isolated from different bacterial species have different biological effects. Even the highly conserved lipid A component of LPS differs slightly between different bacterial species (51, 52). For example, E. coli lipid A usually has 6–8 acyl chains, whereas Yersinia Pestis produces 4 or 6 acyl chains depending on the growth conditions (53). The tetra-acylated LPS from Yersinia Pestis is less virulent, and is thought to be involved in the immune evasion of Yersinia Pestis and the propagation of plague (52). The characteristic structural features of E. coli lipid A, especially its two phosphates, are required to trigger full TLR4/MD-2 activation in human cells (25). We propose that the reason why different acylation variants of lipid A have different biological activities is not primarily because they induce different degrees of MD-2 conformational changes, but because they influence the position of the phosphates in lipid A as it sits upon the hydrophobic groove of MD-2.

Lipid IVa and monophosphorylated lipid A are two lipid A variants that have interesting biological activities. Monophosphorylated lipid A has reduced proinflammatory activity (24), and is being increasingly used as a vaccine adjuvant (54–56). Furthermore, monophosphorylated lipid A has been shown to bias the MyD88-independent pathway (27). To understand the underlying mechanisms, we created series of mutants that abolished interactions with either phosphate of lipid A, and examined the stimulatory activity of lipid A. We found that the removal of charge interactions with either phosphate on lipid A, when present, substantially decreased the stimulatory activity of lipid A. However, the MyD88-dependent and -independent pathways were impaired to the same extent. In other words, the MyD88-independent signaling was not spared from mutagenesis that abolished ionic interactions with either phosphate, contrary to what would be predicted from the findings that monophosphorylated lipid A is a TRIF-biased agonist (27).

Lipid IVa is an LPS agonist in mouse cells but an antagonist in human cells (57). We have previously shown that in the presence of functional mouse MD-2 proteins, human TLR4 gained lipid IVa responsiveness after charge reversal mutagenesis at the dimerization interface, i.e., after the E369K_Q436R mutations (23). Here, we show that in the presence of functional mouse MD-2 proteins, human TLR4 retained lipid IVa responsiveness after the combined mutations of E369K_Q436R at the dimerization interface and R264A_K341A_K362A at Positive Patch 1. Therefore, the loss of ionic interactions at Positive Patch 1 did not impair the ability of the mutant hTLR4/mMD-2 complex to respond to lipid IVa. The importance of these observations is that we can now state with some degree of confidence that ionic interactions at the dimerization interface are the ultimate driving force for the species-specific activation of lipid IVa.

Acknowledgment

Microarrays and protocols were obtained either from the Massachusetts General Hospital Microarray Core in Cambridge, MA, USA or from the Swegene DNA Microarray Resource Center at Lund University, Lund, Sweden (supported by the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation through the Swegene consortium). We thank Brian G. Monks, Najib El Messadi, Alicia Krieger, Danny Park, Johan Staaf and Jeanette Valcich for their expert technical assistance. We also thank Drs. Takashi Kaneko, Charles R. Sweet and Neal Silverman for providing the PGN-free LPS.

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM54060 to D.T.G and U19 AI084048 to J.M. and D.T.G.

Reference

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rangel-Frausto MS. Sepsis: still going strong. Arch Med Res. 2005;36:672–681. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Natanson C, Hoffman WD, Suffredini AF, Eichacker PQ, Danner RL. Selected treatment strategies for septic shock based on proposed mechanisms of pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:771–783. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J, Glauser MP. Septic shock: treatment. Lancet. 1991;338:736–739. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spek CA, Verbon A, Aberson H, Pribble JP, McElgunn CJ, Turner T, Axtelle T, Schouten J, Van Der Poll T, Reitsma PH. Treatment with an anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody delays and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced gene expression in humans in vivo. J Clin Immunol. 2003;23:132–140. doi: 10.1023/a:1022528912387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards G, Levy H, Laterre PF, Feldman C, Woodward B, Bates BM, Qualy RL. CURB-65, PSI, and APACHE II to assess mortality risk in patients with severe sepsis and community acquired pneumonia in PROWESS. J Intensive Care Med. 26:34–40. doi: 10.1177/0885066610383949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poltorak A, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Citterio S, Beutler B. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2163–2167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040565397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randow F, Seed B. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone gp96 is required for innate immunity but not cell viability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:891–896. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lien E, Means TK, Heine H, Yoshimura A, Kusumoto S, Fukase K, Fenton MJ, Oikawa M, Qureshi N, Monks B, Finberg RW, Ingalls RR, Golenbock DT. Toll-like receptor 4 imparts ligand-specific recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;105:497–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr The Toll receptor family and microbial recognition. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:452–456. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01845-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immunity. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:338–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moynagh PN. TLR signalling and activation of IRFs: revisiting old friends from the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagan JC, Su T, Horng T, Chow A, Akira S, Medzhitov R. TRAM couples endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to the induction of interferon-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:361–368. doi: 10.1038/ni1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGettrick AF, O'Neill LA. Localisation and trafficking of Toll-like receptors: an important mode of regulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 22:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HM, Park BS, Kim JI, Kim SE, Lee J, Oh SC, Enkhbayar P, Matsushima N, Lee H, Yoo OJ, Lee JO. Crystal structure of the TLR4-MD-2 complex with bound endotoxin antagonist Eritoran. Cell. 2007;130:906–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resman N, Vasl J, Oblak A, Pristovsek P, Gioannini TL, Weiss JP, Jerala R. Essential roles of hydrophobic residues in both MD-2 and toll-like receptor 4 in activation by endotoxin. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15052–15060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901429200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng J, Lien E, Golenbock DT. MD-2-mediated ionic interactions between lipid A and TLR4 are essential for receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8695–8702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qureshi N, Takayama K, Ribi E. Purification and structural determination of nontoxic lipid A obtained from the lipopolysaccharide of Salmonella typhimurium. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11808–11815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zahringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, et al. Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J. 1994;8:217–225. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Ulmer AJ, Holst O, Brade H, Schmidt G, Mamat U, Grimmecke HD, Kusumoto S, et al. The chemical structure of bacterial endotoxin in relation to bioactivity. Immunobiology. 1993;187:169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mata-Haro V, Cekic C, Martin M, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science. 2007;316:1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen TY, Bright SW, Pace JL, Russell SW, Morrison DC. Induction of macrophage-mediated tumor cytotoxicity by a hamster monoclonal antibody with specificity for lipopolysaccharide receptor. J Immunol. 1990;145:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Couturier C, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Caroff M, Kazatchkine MD. Binding sites for endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) on human monocytes. J Immunol. 1991;147:1899–1904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirkland TN, Virca GD, Kuus-Reichel T, Multer FK, Kim SY, Ulevitch RJ, Tobias PS. Identification of lipopolysaccharide-binding proteins in 70Z/3 cells by photoaffinity cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:9520–9525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golenbock DT, Hampton RY, Raetz CR, Wright SD. Human phagocytes have multiple lipid A-binding sites. Infect Immun. 1990;58:4069–4075. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.12.4069-4075.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright SD, Jong MT. Adhesion-promoting receptors on human macrophages recognize Escherichia coli by binding to lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1986;164:1876–1888. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.6.1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright SD, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ, Ramos RA. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding protein opsonizes LPS-bearing particles for recognition by a novel receptor on macrophages. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1231–1241. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingalls RR, Golenbock DT. CD11c/CD18, a transmembrane signaling receptor for lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1473–1479. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haziot A, Hijiya N, Gangloff SC, Silver J, Goyert SM. Induction of a novel mechanism of accelerated bacterial clearance by lipopolysaccharide in CD14-deficient and Toll-like receptor 4-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:1075–1078. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagai Y, Shimazu R, Ogata H, Akashi S, Sudo K, Yamasaki H, Hayashi S, Iwakura Y, Kimoto M, Miyake K. Requirement for MD-1 in cell surface expression of RP105/CD180 and B-cell responsiveness to lipopolysaccharide. Blood. 2002;99:1699–1705. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorenz E, Patel DD, Hartung T, Schwartz DA. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient murine macrophage cell line as an in vitro assay system to show TLR4-independent signaling of Bacteroides fragilis lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4892–4896. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4892-4896.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humphries HE, Triantafilou M, Makepeace BL, Heckels JE, Triantafilou K, Christodoulides M. Activation of human meningeal cells is modulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and non-LPS components of Neisseria meningitidis and is independent of Toll-like receptor (TLR)4 and TLR2 signalling. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:415–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaneko T, Goldman WE, Mellroth P, Steiner H, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Harley W, Fox A, Golenbock D, Silverman N. Monomeric and polymeric gram-negative peptidoglycan but not purified LPS stimulate the Drosophila IMD pathway. Immunity. 2004;20:637–649. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 2000;165:618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saal LH, Troein C, Vallon-Christersson J, Gruvberger S, Borg A, Peterson C. BioArray Software Environment (BASE): a platform for comprehensive management and analysis of microarray data. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-8-software0003. SOFTWARE0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, Sturn A, Snuffin M, Rezantsev A, Popov D, Ryltsov A, Kostukovich E, Borisovsky I, Liu Z, Vinsavich A, Trush V, Quackenbush J. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eichler GS, Huang S, Ingber DE. Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI): for integrative analysis of expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2321–2322. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hosack DA, Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R70. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-10-r70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fitzgerald KA, Palsson-McDermott EM, Bowie AG, Jefferies CA, Mansell AS, Brady G, Brint E, Dunne A, Gray P, Harte MT, McMurray D, Smith DE, Sims JE, Bird TA, O'Neill LA. Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature. 2001;413:78–83. doi: 10.1038/35092578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schromm AB, Lien E, Henneke P, Chow JC, Yoshimura A, Heine H, Latz E, Monks BG, Schwartz DA, Miyake K, Golenbock DT. Molecular genetic analysis of an endotoxin nonresponder mutant cell line: a point mutation in a conserved region of MD-2 abolishes endotoxin-induced signaling. J Exp Med. 2001;194:79–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meng J, Drolet JR, Monks BG, Golenbock DT. MD-2 residues tyrosine 42, arginine 69, aspartic acid 122, and leucine 125 provide species specificity for lipid IVA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27935–27943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bjorkbacka H, Fitzgerald KA, Huet F, Li X, Gregory JA, Lee MA, Ordija CM, Dowley NE, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. The induction of macrophage gene expression by LPS predominantly utilizes Myd88-independent signaling cascades. Physiol Genomics. 2004;19:319–330. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00128.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagai Y, Akashi S, Nagafuku M, Ogata M, Iwakura Y, Akira S, Kitamura T, Kosugi A, Kimoto M, Miyake K. Essential role of MD-2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:667–672. doi: 10.1038/ni809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dziarski R, Gupta D. Role of MD-2 in TLR2- and TLR4-mediated recognition of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and activation of chemokine genes. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6:401–405. doi: 10.1179/096805100101532243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dixon DR, Darveau RP. Lipopolysaccharide heterogeneity: innate host responses to bacterial modification of lipid a structure. J Dent Res. 2005;84:584–595. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montminy SW, Khan N, McGrath S, Walkowicz MJ, Sharp F, Conlon JE, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Sweet C, Miyake K, Akira S, Cotter RJ, Goguen JD, Lien E. Virulence factors of Yersinia pestis are overcome by a strong lipopolysaccharide response. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1066–1073. doi: 10.1038/ni1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raman VS, Bhatia A, Picone A, Whittle J, Bailor HR, O'Donnell J, Pattabhi S, Guderian JA, Mohamath R, Duthie MS, Reed SG. Applying TLR Synergy in Immunotherapy: Implications in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J Immunol. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fox CB, Friede M, Reed SG, Ireton GC. Synthetic and Natural TLR4 Agonists as Safe and Effective Vaccine Adjuvants. Subcell Biochem. 53:303–321. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9078-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fusco WG, Afonina G, Nepluev I, Cholon DM, Choudhary N, Routh PA, Almond GW, Orndorff PE, Staats H, Hobbs MM, Leduc I, Elkins C. Immunization with the Haemophilus ducreyi Hemoglobin Receptor HgbA with Adjuvant Monophosphoryl Lipid A Protects Swine from a Homologous but not a Heterologous Challenge. Infect Immun. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00217-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Golenbock DT, Hampton RY, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Raetz CR. Lipid A-like molecules that antagonize the effects of endotoxins on human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19490–19498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]