Abstract

Background

Hip osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disabling disease, which has a much higher prevalence in Caucasians than Asians. The reasons for this ethnic difference in prevalence are unknown. Hip OA often is thought to be secondary to morphologic abnormalities. If particular abnormalities predisposing to hip OA occur more frequently in Caucasians, these differences in hip shape could account for prevalence differences.

Methods

A morphometric study was performed using 400 non-osteoarthritic hips of 200 women participants from 2 studies: the Beijing OA study and the SOF study from the U.S. We focused on measures of hip dysplasia and impingement (Lateral Center Edge Angle, Impingement Angle, Acetabular Slope, Femoral Head Neck Ratio and the Cross Over Sign) and compared data from Chinese and Caucasian hips.

Results

Compared with their Chinese counterparts, Caucasian women had a lower mean impingement angle (83.6° vs. 87.0°’ p=.03) and were more likely to have center edge angles suggestive of impingement (for center edge angle >35°, 11% of Chinese vs. 23% of Caucasian hips, p = .008). On the other hand, low center edge angles suggesting dysplasia were found more often in Chinese women (for <20°, 22% of Chinese vs. 7% of Caucasian hips, p = .005).

Conclusions

In a study of elderly women without signs of OA, the morphometry of impingement and asphericity were more common in Caucasian than Chinese hips. Our findings suggest that Caucasians may be at higher risk of hip OA than Chinese because of morphologic findings that predispose them to femoro-acetabular impingement.

Introduction

Symptomatic disabling hip osteoarthritis (OA) occurs in approximately 3% of persons age 30 years and older in the U.S. (1). Among factors responsible for the development of OA are genetic factors, obesity, overuse, and traumatic injury (2–6). Overt forms of deformity caused by developmental problems such as developmental dysplasia (DDH), Perthes disease and slipped capital femoral epiphysis cause hip OA in early adulthood (7–9). Murray (9), Stulberg (10) and Harris (7) recognized that in addition to these major deformities, milder forms of these or other deformities may be responsible for much adult onset hip OA. To date, only mild hip dysplasia has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for incident hip OA among Caucasian elderly females (11).

Among mild developmental abnormalities suggested to cause hip OA are a non-spherical “pistol grip deformity” of the femoral head and neck which can predispose to femoroacetabular impingement. The latter entity occurs when, during hip motion, the femoral head or neck impinges against the acetabulum, causing damage to structures inside the hip joint. Such impingement could occur because of femoral head/neck deformities (so-called cam impingement) or because of acetabular deformities such as over-coverage or retroversion (so-called pincer impingement) (12;13). Recently Ganz and others demonstrated that pistol grip bony deformity cause significant damage in hips even before radiographic evidence of OA (14;15).

Currently, it is thought that for long lasting pain free functioning of a hip joint an optimum femoral head coverage by the acetabulum is required (7;14;16). Lack of coverage, such as occurs in acetabular dysplasia, can lead to instability and overloading of the articular cartilage, which may then lead to joint degeneration. Conversely, over-coverage such as occurs in acetabular protrusion or acetabular retroversion may also cause symptoms of pain in the hip due to the pincer-type internal impingement between the femoral head-neck junction and the acetabulum. Even with optimal acetabular coverage, a femoral head-neck junction that is too broad or aspherical may cause symptoms of pain due to a cam-type impingement. These subtle anatomic abnormalities often occur in combination.

Hip OA has a heterogeneous geographical distribution perhaps accounted for by racial and ethnic disparities in occurrence (17;18). Large scale population based studies assessing hip pain and obtaining x-rays of participants have shown that hip OA prevalence in Chinese populations is approximately one tenth the prevalence of hip OA in Caucasian groups of the same age and gender (5;19). Even the rate of total hip replacements is much higher in Caucasians than Asians as shown in a mixed ethnic population from Hawaii (20;21). Caucasians in San Francisco have an incidence of total hip replacement for OA that was 1520 times the rate for Asians there (17). Hip OA is most common in Western countries like the US and northern Europe. The hip OA difference is not mirrored by similar prevalence differences in other joints, suggesting that there is not a similar difference in generalized OA. Knee OA is actually more prevalent in Chinese compared to Caucasians (22), and there is a similar prevalence of hand OA (19).

The ethnic differences in hip OA prevalence could be explained by subtle morphologic differences in the hip joint with morphologies that are likely to predispose to hip OA being more common in Caucasian populations. The aim of this study was to compare morphometric differences in non-osteoarthritic hip joints between Chinese and Caucasian cohorts using x-rays obtained in population-based surveys of elderly women from Beijing, China and Caucasians from the United States. We hypothesized that subtle differences in acetabular coverage and orientation and femoral head sphericity could be detected on radiographs and may be responsible for the high prevalence of hip OA seen in Caucasian populations relative to Asians. We focused on hips without OA because of the boney remodeling that occurs with disease development, remodeling which may mimic some of the morphologic changes of interest. We limited our study to women because we had used identical protocols to acquire hip x-rays in studies of Caucasian women and Chinese women, making it likely that any differences we saw in morphology were unlikely to be due to different radiographic techniques.

Materials and Methods

Study Cohorts: Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) – This is a multicenter cohort study of risk factors for fractures in 9,704 white women ages ≥65 years recruited from Sept. 1986 to Oct. 1988. Details of this study have been described (23;24). Standard supine AP Pelvis radiographs with feet fixed at 15–30 degrees of internal rotation and centered on the symphysis pubis were performed on all subjects at the baseline SOF examination (25;26).

The Beijing OA (BOA) study including door to door recruitment of all persons ≥60 years old from randomly selected neighborhoods in Beijing was carried out to investigate the prevalence of osteoarthritis in hands, knees and hips among elders in Beijing. As part of the study, standard supine AP pelvis radiographs of all subjects were obtained. The sampling frame and recruitment approach has been described (22). Pelvis radiographs were obtained at Peking Union Medical College Hospital using the SOF protocol (see above).

In these studies, hip radiographs were read using a standard approach for OA (27). Beijing Study and SOF films were read by the same panel of readers using the same approach (7;24). To identify hips without OA, we selected hip films where, for both hips, there were no features of OA (for both cohorts, none of the following features could be present: osteophyte >=2 (0–3 scale) joint space narrowing scores were >=2 (0–3 scale), minimal joint space <2.5mm or any combination of 2 or more individual radiographic features (sclerosis, cysts, osteophytes, narrowing scored semiquantitatively) (28).

We measured morphometric parameters on one hundred such pelvic radiographs that were randomly selected from persons without radiographic OA in either hip (a total of 200 radiographs containing 400 hip joints) from each of the above study cohorts. The Chinese female cohort was obtained from the Beijing OA Study, while the Caucasian females were obtained from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Films from the two studies were mixed together to limit the effect of drift in measurement on comparative results.

Hip Morphological Assessment: Femoral head coverage by the acetabulum was assessed by the Center-edge angle of Wiberg (29) and the acetabular slope of Tönnis (also called Tönnis angle and HTE) (30) (Fig.1). Acetabular retroversion was assessed by the cross over sign (31) (Fig.2). Femoral head asphericity was assessed using the impingement angle (32) (Fig.3) and the femoral head ratio of Murray (9) (Fig.4). Details regarding the radiographic measurement technique are provided in the figure legend. We did not include figures for Center-edge angle and cross over signs as they are widely used. Center edge angle is the angle between a vertical line extending up from the femoral head center and another line also originating at the femoral head center which passes to the edge of the acetabulum. A positive cross over sign (33–38) exists when the anterior and posterior walls of the acetabulum cross over the femoral head. (A hip with a normal pelvic inclination should have the anterior and posterior lips join at the edge of the acetabulum). A positive cross-over sign may indicate acetabular retroversion or anterior overcoverage.

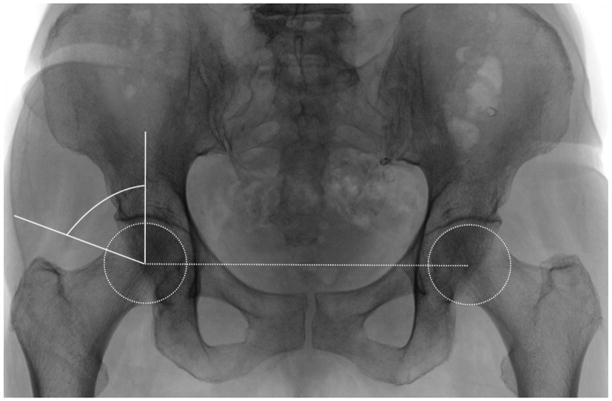

Figure 1.

Acetabular slope of Tönnis (16;30;55;56). A horizontal line is drawn connecting the femoral head centers. The angle formed by the horizontal line and the line connecting the edges of the acetabular sourcil is the acetabular slope of Tönnis.

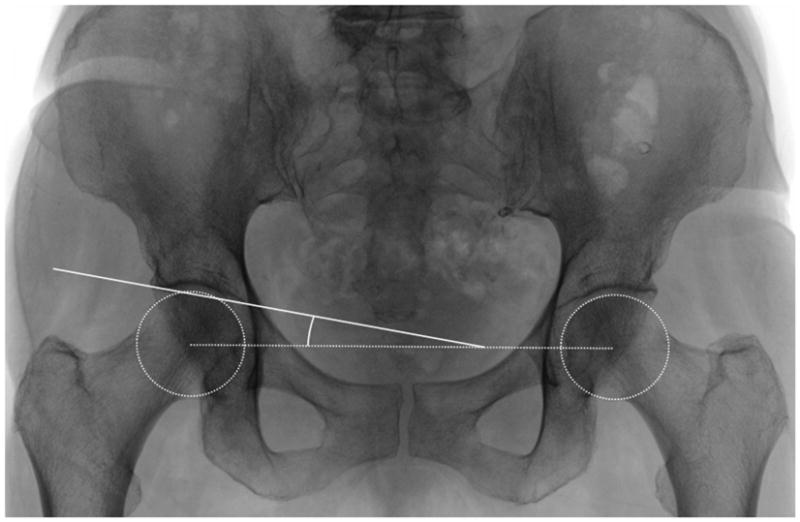

Figure 2.

Impingement Angle (32;37). A perfect circle is drawn that encompasses the inferior and superior portion of the femoral head. A line passing through the center of the both femoral heads is found and used as a reference line. An angle is formed by drawing a perpendicular line to the horizontal reference line and a line connecting the center of the femoral head to the first part of the lateral femoral head, which is outside the perfect circle. An angle < 70° is defined as pathologic, assuming a neck shaft angle in adults is on average 130°.

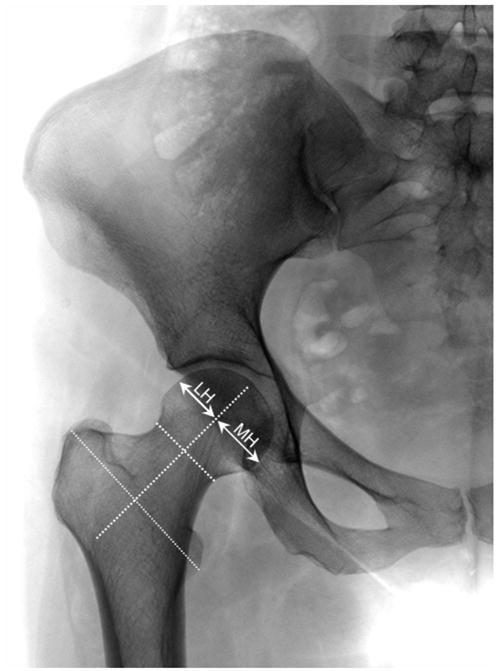

Figure 3.

Femoral head ratio of Murray (9). Ratio of the femoral head width lying on each side of a line drawn through the middle of the femoral neck and middle of the line connecting the greater and lesser trochanters. A larger ratio implies a more “pistol grip” shape of the femoral head. In females, FHR has a mean of 0.92 with range of 0.66 to 1.36 and for males FHR a mean of 1.17 with range of 0.62 to 1.92.

The radiographs were mixed and read independently by two orthopaedic surgeons (MD, YJK). Prior to reading the readers were trained and retrained on the measurement protocol. Both the inter-and intra-reader reliabilities were high, with intra-and interobserver intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 0.97.

In addition to the measures of dysplasia and impingement above, we used accepted cutpoints of continuously measured angles to determine whether Chinese hips differed from Caucasian hips in terms of either measures of dysplasia or impingement. We used the following criteria for thresholds that constituted abnormal hip morphology dividing these into measures of hip dysplasia (acetabular undercoverage) vs. impingement: Measures of hip dysplasia:

center-edge angle less than 20 degrees (29) or 16 degrees (31)

acetabular slope greater than 10 degrees or greater than 15 degrees (16;30)

Measures of impingement/overcoverage:

center-edge angle greater than 35° or 40° (suggests pincer type impingement) (16).

Acetabular slope of Tonnis: where less than 0 degrees is considered to be acetabular over-coverage (16) (suggests pincer type impingement).

Impingement angle thresholds are based on the thresholds used for the alpha angle of Notzli and normal neck shaft angle (39). Impingement angle less than 70° was considered to be a hip with a cam type impingement. Impingement angle is related but different from the alpha angle of Notzli. The impingement angle also takes into account proximal femoral varus and valgus angulation and is decreased in varus neck angulation, which, for the same proximal femoral deformity with the same alpha angle accentuates impingement.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated mean values of center-edge angle, acetabular slope, and femoral head ratio for Chinese and Caucasians. We carried out a linear regression to evaluate whether continuously defined center-edge angle, acetabular slope, and femoral head ratio were different between Chinese and Caucasians.

We also calculated the proportion of measures of impingement (CE angle (>35 degrees), impingement of acetabular slope (<0 degrees), and femoral head ratio (>1.35)) for each sex among Chinese and Caucasians and compared the difference of proportion of each measure between Chinese and Caucasians using a logistic regression model (dependent variable was the morphometric measure; independent variable was ethnic group). Since each subject provided data from both left and right hips, we used generalized estimating equations with robust standard errors to account for the correlation between two sides within a subject.

Results

Those selected for our study were similar in age, educational attainment and BMI to the larger cohorts from which they were drawn (see table 1). One of the Beijing subject’s hip films were not clear enough for the hips to be measured, leaving 99 subjects from Beijing. All selected subjects in SOF (and almost all subjects in the parent study) were Caucasian ethnicity. The mean age in Caucasian women in our studied sample was 71.0 years vs. 70.7 years in Chinese (p = .66 using t test). Mean BMI was 26.5 in Caucasian women vs. 25.5 in Chinese (p <.001). Subjects were selected so as not to have radiographic hip OA in either hip. Of the SOF and BOA hips, all had Croft scores of 0 or 1. Croft grade 1’s represent possible osteophytes or possible narrowing. These particular hips had either medial narrowing scores or acetabular osteophyte scores of 1 neither of which is typically indicative of osteoarthritis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) and in the Beijing Osteoarthritis (BOA ) Study

| Variable | SOF (n=9704) | SOF subjects in this study (n=100) | BOA (n=1505) | BOA subjects in this study (n=99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 71.7 ± 5.3 | 71.0 ± 4.8 | 67.5 ± 6.1 | 70.7 ± 5.2 |

| Education, >=12 years, % | 7461 (76.9%) | 82 (82%) | 168 (11.2%) | N.A. |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 4.7 | 26.8 ± 4.2 | 25.5 ± 4.2 | 22.5 ± 4.2 |

| Hip pain, % (for at least a month in past 12 month), person-based | 30.4% | 31% | 12.7% | 7.2% |

As shown in Table 2, the mean center-edge angle of Wiberg for Caucasian women (mean =30.3°, SD= 7.7) was significantly greater than that for Chinese (mean=25.7°, SD=7.3) (p<0.001). Similarly, Chinese women had a higher acetabular slope of Tönnis than Caucasian women suggesting that the Chinese hips were less covered than the Caucasian hips.

Table 2.

Morphological differences between Chinese and Caucasian female hips

| Radiographic measurements | Caucasian | Chinese | Adjusted P-value* from comparing means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impingement angle, mean (SD) | 83.6 (13.4) | 87.0 (8.4) | 0.009 |

| Femoral Head Ratio, mean (SD) | 0.88 (0.25) | 0.90 (0.22) | 0.63 |

| Acetabular Slope, mean (SD) | 3.8 (5.1) | 6.7 (5.1) | <.0001 |

| Center Edge Angle, mean (SD) | 30.3 (7.7) | 25.7 (7.3) | <.0001 |

| Femoral Head Ratio >1.35 (%) | 4.0 | 3.1 | 0.62 |

p values represent least squares means for ethnicity in linear regression in which radiographic measure was the dependent variable and independent variables were age, height, BMI and ethnicity.

No difference was observed in the femoral head ratio of Murray between two ethnic groups. However, the average impingement angle was 83.6° (SD=13.4) for the Caucasian women and 87° (8.4) for Chinese women (p=0.009), suggesting that the Caucasian hips were more aspherical. The cross over sign (acetabular retroversion) was slightly more prevalent in Chinese than in Caucasians, but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Using the threshold values for center edge angle, acetabular slope of Tönnis, Impingement angle, and Femoral head ratio to define the percentage of hips that were thought to be normal vs. abnormal, Table 3 shows the differences found. Using the center edge angle >35, Acetabular slope <0, and Impingement angle <70, hips that would be predisposed to impingement were more commonly seen in the Caucasian hips. Of these high center edge angle and low acetabular slopes point to pincer type impingement, and the low impingement angle is compatible with cam type impingement. In the female Chinese hips, center edge angle <20, acetabular slope >10, factors suggesting undercoverage, were more prevalent. However, when the more strict criteria LCE <16 and acetabular slope >15 for undercoverage were used, Chinese hips had no significant increase in the number.

Table 3.

Comparing hip anatomic features between Caucasians and Chinese women: Testing the frequency of impingement and instability and other abnormalities using accepted cutpoints

| Chinese (99 subjects) vs. American (100 subjects) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N of hip | N with feature (%) | Chinese vs. Whites Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| CE Angle | |||||

| >35° Impingement | Whites | 200 | 46 (23.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 22 (11.11) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.01 | |

| <40° Impingement | Whites | 200 | 18 (9.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 8 (4.04) | 0.4 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.13 | |

| <20° Instability | Whites | 200 | 14 (7.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 43 (21.72) | 3.1 (1.6, 6.1) | 0.001 | |

| <16° Instability | Whites | 200 | 5 (2.50) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 13 (6.57) | 2.6 (0.8, 8.7) | 0.11 | |

| Acetabular Slope | |||||

| <0° Impingement | Whites | 200 | 26 (13.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 6 (3.03) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.004 | |

| >10° Instability | Whites | 200 | 15 (7.50) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 37 (18.69) | 2.5 (1.2, 5.1) | 0.01 | |

| >15° Instability | Whites | 200 | 2 (1.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 9 (4.55) | 4.5 (0.5, 37.7) | ||

| Impingement Angle | |||||

| <70° Impingement | Whites | 199 | 24 (12.06) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 7 (3.54) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.009 | |

| Femoral Head Ratio of Murray | |||||

| >1.35 | Whites | 199 | 8 (3.02) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 196 | 6 (3.06) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.2) | 0.62 | |

| Acetabular Retroversion = N | Whites | 200 | 162 (81.00) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| Chinese | 198 | 172 (86.87) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) | 0.19 | |

Prevalence ratios derived from logistic regression in which the dependent variable was the morphologic abnormality dichotomized and the independent variables were ethnicity, age, height and BMI.

Discussion

The prevalence of hip OA has been found to be much higher in Caucasian than in Asian hips in several studies (5;12;13;40); however, the reasons for these differences are unclear. What puts Caucasian hips at risk? This study demonstrated that female Caucasian hips are more often overcovered and less spherical than hips from Chinese women, suggesting that Caucasian hips are more susceptible to femoroacetabular impingement. Of note, mild dysplasia was not more common in Caucasian hips. If anything, it was more prevalent among the Chinese.

Recent studies suggest that structural abnormalities in terms of acetabular undercoverage, acetabular overcoverage, and femoral head asphericities are an important factor in the development of hip OA. In particular, femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI) is increasingly recognized as factor in the development and progression of hip OA (14;15;41). Although non-spherical head shape has been suggested as a risk factor for hip OA in one cross-sectional study (42), it remains unclear as to whether morphological variants thought to lead to impingement predispose to hip OA. Our data showing a higher prevalence of the morphology related to FAI in Caucasians who, in turn, have higher rates of hip OA, provides circumstantial evidence that these morphologic changes can also be implicated as causes of hip OA.

Acetabular dysplasia can lead to premature OA (11;43), but the importance of milder forms of this anatomic abnormality as a major cause of OA has been debated. Some studies suggest that as much as 40% of hip OA can be due to hip dysplasia (7;9;44). However, large prospective studies have shown hip dysplasia to be a minor risk factor for hip OA in women (11). Others report that in Chinese the prevalence was as high as in Caucasian hips, so that the low rate of OA of the hip is likely not caused by a rarity of hip dysplasia in Chinese population (45). As in our study of Chinese, in the Japanese population it was shown that there is a higher prevalence of dysplasia but a low prevalence of hip OA (13).

A possible explanation for the protection of Asian hips against OA is that because of a more shallow acetabulum in Chinese, there is more space for motion of the hip, and our results show that additionally in Chinese women the impingement angle is significantly greater, so the femoral head is more spherical than in Caucasian women. The shallow acetabulum and the more spherical femoral head may protect against impingement syndrome and in turn, against OA. Biomechanical modeling of hips with various amounts of coverage and femoral asphericity suggests that less acetabulular coverage protects a hip with aspherical femoral head from impinging (46).

Femoroacetabular impingement has two overlapping subtypes, cam and pincer deformities and of these, pincer may be more prevalent among women (47). Our measures of pincer deformity include those for overcoverage (large center edge angles and acetabular slope impingement) show higher prevalence of overcoverage in Caucasians. Interestingly, even though cam impingement is not necessarily as common in women as men, even our morphometric measure of this, the impingement angle measure, showed that cam deformities were more prevalent in Causcian than Chinese women.

What else could account for the marked difference in hip OA prevalence among these ethnic groups? Ethnic differences in BMI may explain the variations (48). An increased BMI increases the risk of OA in hips, but the association of obesity with hip OA is weaker than in knees (49), with at most a 2 fold increase in risk among those who are obese (compared with the 10 fold higher risk of hip OA in Caucasians) (50). The modest effect of obesity on hip OA risk could not be expected to account for this marked ethnic difference (19).

Genetic factors may also explain ethnic differences in the occurrence of hip OA. Hip OA has a heritability approaching 60% in some studies (28;51–54). In fact, the heritability of hip OA is likely to be accounted for by anatomic/morphological factors. For example, hip OA runs in families separately from OA in other joints (53). One compelling explanation for such heritability would be the inheritance of a morphological variant that would predispose some members of a family to hip OA. Such a variant could also account for some of the ethnic difference in hip OA (21;53).

In this study we found significant differences for acetabular slope, center edge angle and impingement angle but not for the femoral head ratio of Murray, another measure which would point to femoroacetabular impingement. The femoral head neck ratio may not be measured accurately enough on an AP hip film to distinguish between morphological differences in Chinese and Caucasian hips.

There were important limitations to our study. For one, it was not longitudinal. Ideally an investigation of hip OA causes implicating the morphologic findings we discussed should track these findings longitudinally and document that they cause OA. We did not do that, although numerous studies now point to femoro-acetabular impingement and its measures as probable causes of hip OA and clear-cut causes of disease progression. A prospective study of morphometric causes of hip OA in Chinese is probably not feasible given the rarity of disease. In our large scale survey (1800 older subjects with pelvis films), we could not find enough cases of hip OA to carry out risk factor studies and any retrospective study would be limited since the boney remodeling that occurs as a consequence of hip OA would make pre-morbid hip anatomy impossible to assess in cases with extant OA. Given the rarity of hip OA in Chinese and the lack of validity of retrospective approaches, our approach of examining unaffected persons to evaluate predisposing hip morphology may be among the best possible approaches to get insight into the reasons for this ethnic difference. Studies using new imaging modalities more sensitive to mild changes of OA may be an alternative approach. Our study is also potentially limited in studying only elderly women. We only had comparable x-ray techniques only in women from cohorts in the U.S. and China. We note that the prevalence of hip OA is low in both sexes in China and much higher in both sexes in the Western world and that impingement is not a gender specific finding. Also, similar pelvic radiographic views were taken for women subjects. Studies in men need to be carried out. Also, to the extent that morphometric abnormalities would have been expected to exert their influence on disease development at an earlier age than women in our study, we might have missed important effects.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Caucasian women have more over-coverage and less sphericity of their hips than Chinese women. This may put them at higher risk of hip OA than Chinese. These findings suggest more frequent femoro-acetabular impingement in Caucasian hips. It is possible that this impingement may cause hip OA and account for the high rate of OA in Caucasian hips.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH AR47785

References

- 1.Felson DT, Zhang Y. An update on the epidemiology of knee and hip osteoarthritis with a view to prevention. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(8):1343–55. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199808)41:8<1343::AID-ART3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mototani H, Mabuchi A, Saito S, Fujioka M, Iida A, Takatori Y, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in the core promoter region of CALM1 is associated with hip osteoarthritis in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(8):1009–17. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loughlin J. Polymorphism in signal transduction is a major route through which osteoarthritis susceptibility is acting. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(5):629–33. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000176687.85198.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loughlin J. The genetic epidemiology of human primary osteoarthritis: current status. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7(9):1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nevitt MC, Xu L, Zhang Y, Lui LY, Yu W, Lane NE, et al. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing, China, compared with whites in the United States: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(7):1773–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nevitt MC. Obesity outcomes in disease management: clinical outcomes for osteoarthritis. Obes Res. 2002;10 (Suppl 1):33S–7S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris WH. Etiology of Osteoarthritis of the Hip. Clin Orthop. 1986;(213):20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HARRIS LE, LIPSCOMB PR, HODGSON JR. Early diagnosis of congenital dysplasia and congenital dislocation of the hip. Value of the abduction test. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;173:229–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020210009003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38(455):810–24. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stulberg SD, Cordell LD, Harris WH, Ramsey PL, MacEwen GD. Unrecognized childhood hip disease: A major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip. Proceedings of the Third Open Scientific Meeting of the Hip Society; 1975. pp. 212–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane NE, Lin P, Christiansen L, Gore LR, Williams EN, Hochberg MC, et al. Association of mild acetabular dysplasia with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in elderly white women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):400–4. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<400::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau EM, Lin F, Lam D, Silman A, Croft P. Hip osteoarthritis and dysplasia in Chinese men. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(12):965–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.12.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshimura N, Campbell L, Hashimoto T, Kinoshita H, Okayasu T, Wilman C, et al. Acetabular dysplasia and hip osteoarthritis in Britain and Japan. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(11):1193–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.11.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(417):112–20. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(7):1012–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tonnis D. Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of X-rays in children and adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;(119):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoaglund FT, Oishi CS, Gialamas GG. Extreme variations in racial rates of total hip arthroplasty for primary coxarthrosis: a population-based study in San Francisco. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(2):107–10. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoaglund FT, Shiba R, Newberg AH, Leung KY. Diseases of the hip. A comparative study of Japanese Oriental and American white patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(9):1376–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoaglund FT, Yau AC, Wong WL. Osteoarthritis of the hip and other joints in southern Chinese in Hong Kong. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(3):545–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oishi CS, Hoaglund FT, Gordon L, Ross PD. Total hip replacement rates are higher among Caucasians than Asians in Hawaii. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(353):166–74. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199808000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lohmander LS, Engesaeter LB, Herberts P, Ingvarsson T, Lucht U, Puolakka TJ. Standardized incidence rates of total hip replacement for primary hip osteoarthritis in the 5 Nordic countries: similarities and differences. Acta Orthop. 2006;77(5):733–40. doi: 10.1080/17453670610012917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Xu L, Nevitt MC, Aliabadi P, Yu W, Qin M, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis between the elderly Chinese population in Beijing and whites in the United States: The Beijing Osteoarthritis Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(9):2065–71. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<2065::AID-ART356>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nevitt MC, Lane NE, Scott JC, Hochberg MC, Pressman AR, Genant HK, et al. Radiographic osteoarthritis of the hip and bone mineral density. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(7):907–16. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(12):767–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ensrud KE, Blackwell T, Mangione CM, Bowman PJ, Bauer DC, Schwartz A, et al. Central nervous system active medications and risk for fractures in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(8):949–57. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siguier T, Siguier M, Brumpt B. Mini-incision anterior approach does not increase dislocation rate: a study of 1037 total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(426):164–73. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000136651.21191.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croft P, Cooper C, Wickham C, Coggon D. Defining osteoarthritis of the hip for epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(3):514–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanyon P, Muir K, Doherty S, Doherty M. Assessment of a genetic contribution to osteoarthritis of the hip: sibling study. BMJ. 2000;321(7270):1179–83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7270.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint, with special references to the complications of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand. 1939;58:5–135. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tonnis D. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. Springer; NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharp IK. Aceabular dysplasia. The acetabular angle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1961;43B:268–72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(2):281–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siebenrock KA, Schoeniger R, Ganz R. Anterior femoro-acetabular impingement due to acetabular retroversion. Treatment with periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):278–86. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200302000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siebenrock KA, Kalbermatten DF, Ganz R. Effect of pelvic tilt on acetabular retroversion: a study of pelves from cadavers. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(407):241–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200302000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1747–70. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199912000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Decreased acetabular anteversion and femur neck antetorsion cause pain and arthrosis. 2: Etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1999;137(2):160–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonnis D, Heinecke A. Decreased acetabular anteversion and femur neck antetorsion cause pain and arthrosis. 1: Statistics and clinical sequelae. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1999;137(2):153–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Notzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(4):556–60. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.84b4.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lau EM, Symmons DP, Croft P. The epidemiology of hip osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis in the Orient. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(323):81–90. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck M, Leunig M, Parvizi J, Boutier V, Wyss D, Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement: part II. Midterm results of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(418):67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doherty M, Courtney P, Doherty S, Jenkins W, Maciewicz RA, Muir K, et al. Nonspherical femoral head shape (pistol grip deformity), neck shaft angle, and risk of hip osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(10):3172–82. doi: 10.1002/art.23939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Cooper C, Pressman A, Gore R, Hochberg M. Acetabular dysplasia and osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56(10):627–30. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.10.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon L. Patterns of osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58(2):176–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.58B2.932079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau E, Symmons D, Bankhead C, MacGregor A, Donnan S, Silman A. Low prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in the urbanized Chinese of Hong Kong. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(7):1133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chegini S, Beck M, Ferguson SJ. The effects of impingement and dysplasia on stress distributions in the hip joint during sitting and walking: a finite element analysis. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(2):195–201. doi: 10.1002/jor.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfirrmann CW, Mengiardi B, Dora C, Kalberer F, Zanetti M, Hodler J. Cam and pincer femoroacetabular impingement: characteristic MR arthrographic findings in 50 patients. Radiology. 2006;240(3):778–85. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403050767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clark AG, Jordan JM, Vilim V, Renner JB, Dragomir AD, Luta G, et al. Serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein reflects osteoarthritis presence and severity: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(11):2356–64. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199911)42:11<2356::AID-ANR14>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, Hirsch R, Helmick CG, Jordan JM, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):635–46. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, McAlindon T, Dieppe PA, Minor MA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 2: treatment approaches. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(9):726–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-9-200011070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ingvarsson T, Stefansson SE, Hallgrimsdottir IB, Frigge ML, Jonsson H, Jr, Gulcher J, et al. The inheritance of hip osteoarthritis in Iceland. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(12):2785–92. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2785::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ingvarsson T, Lohmander S. Icelandic genealogical registry sheds light on the significance of heredity in osteoarthritis. Lakartidningen. 2002;99(47):4724–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spector TD, Cicuttini F, Baker J, Loughlin J, Hart D. Genetic influences on osteoarthritis in women: a twin study. BMJ. 1996;312(7036):940–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spector TD, MacGregor AJ. Risk factors for osteoarthritis: genetics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12 (Suppl A):S39–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tonnis D. The prearthrotic deformity as origin of coxarthrosis. Radiographic measurements and their value in the prognosis. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1978;116(4):444–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tonnis D, Letz A. Behavior of acetabular roof angle and femoral neck angle following intertrochanteric derotating varisation osteotomy; indication for acetabuloplasty. Arch Orthop Unfallchir. 1969;66(3):171–91. doi: 10.1007/BF00416048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]