Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease and one of the main causes of mortality in developing countries. The main objective of treating all chronic diseases, of course, is to improve well-being and attain a satisfactory quality of life (QOL). The major goal of this study is comparison of attitude toward QOL in insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus and healthy subjects.

Methods

In this study, insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus and healthy subjects were gathered via convenience sampling. The subjects were asked to complete the Hanestad & Albrektsen Attitude to Quality of Life Questionnaire. The questionnaire evaluates five quality of life dimensions-physical, social, mental-emotional, behavioral-activity, and economic-using a scoring system similar to the Likert scale. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare scores between the two groups.

Results

The mean total score on attitude toward QOL in the healthy control group was 53.8, and it in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group was 35.9. The mean total score of attitude toward QOL in the physical dimension, mental-emotional and feelings of well-being dimension, and behavioral-activity dimension were significantly higher in the healthy population than they were in diabetes mellitus groups. Such a difference was not seen in the social and economic dimensions.

Conclusion

Since the attitudes of insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus toward QOL are used as an index of individual and societal health levels, it appears that this group may benefit from education and professional counseling to improve their QOLs.

Keywords: Attitude, Diabetes mellitus, Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is one of the highest prevalence chronic diseases with an increasing incidence in the world. According to reports by World Health Organization (WHO), more than 170 million people worldwide are affected by this disease, and this figure is increasing due to increased life expectancy and reduced physical activity [1]. With its acute and chronic effects, this disease is one of the main causes of mortality in developing countries [2]. Treatment statistics from 2002 indicate that 56.8% of males and 68.5% of females are treated with oral medication, and 4% of males and 5.3% of females are using insulin to treat their diabetes mellitus [3]. According to the latest epidemiological studies on diabetes mellitus in Iran, 8.7% of people over 25 years are affected by diabetes mellitus. People who take insulin may suffer consequences of the disease that can cause individual performance disorders, as well as interruptions in their personal and social lives [4].

Although identifying the concerns of people with diabetes mellitus and the barriers to using insulin can help determine some dimensions of quality of life (QOL) in these subjects, various factors may be influential [5]. Since QOL might be influenced by clinical changes resulting from the disease, obtaining information in this field can have advantages for identifying those at high-risk [6].

There is a reciprocal relationship between disease severity and QOL. Due to a relatively high prevalence of insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus in society today, the short and long-term effects of the disease and the high costs imposed on health care systems, the evaluation of QOL in diabetes mellitus subjects would be useful for assessing potential treatment options [7].

QOL is an important indicator of the effectiveness of health care delivery and safety levels and can be used to help anticipate mortality events and hospitalization rates [8,9]. The main objective of treating all chronic diseases, of course, is to improve well-being and attain a satisfactory QOL [10]. This objective might not be achievable without studying the attitudes of subjects toward QOL [11]. In addition, assessing attitudes toward QOL can foster the relationships between patients and health care providers, which may result in increased patient awareness of their disease [12].

In this study, we compared the attitudes of insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus toward QOL with those of a healthy population.

METHODS

Study design and measurement tools

This was a cross-sectional study comparing the attitudes of insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus with those of healthy people (a control group) toward QOL. Attitude toward QOL was the main study variable. Using Hanestad & Albrektsen's Attitude to Quality of Life Questionnaire, we evaluated the subjects' reactions to five dimensions of life quality: the physical, mental-emotional Psycho affect and well-being dimension and Mental and well-being dimension). becuase I mean mental-emotional is psycho affect and well-being dimension and Mental and well-being dimension. The questionnaire required less than 20 minutes to complete and included 47 questions that were answered using the Likert scale. For the physical dimension questions, the possible scores were as follows: very good, +3; good, +2; average, +1; neutral, 0; slightly bad, -1; bad, -2; very bad, -3. Eight questions were related to the social dimension, with scores of increased, 1; unchanged, 0; reduced, -1. Twenty-three questions were related to feelings of well-being, with ratings of very good, 3; good, 2; not bad, 1; bad, 0; not present, -1. Seven questions were related to the behavioral-activity dimension (increased, 1; unchanged, 0; reduced, -1) and five questions focused on the economic or financial dimension (increased, 1; unchanged, 0; reduced, -1). For each of the questions, a negative score indicates an unpleasant result. The scores were also summed for a total score, with a possible range between -55 and +101.

A checklist was used to collect subject demographic data, including age, sex, education, current occupation, and monthly income, as well as to gather information on social habits and any recent stressful events.

Study population

The study population comprised insulin-treated subjects with diabetes mellitus who are between 20 and 60 years of age currently treated with insulin, for more than one year, and had medical records at the Diabetes Research, Education and Treatment Center of Isfahan. The appropriate sample size to achieve a 90% confidence level was 102 cases for each group. The study population was chosen among qualified individuals using a convenience sampling method that took place over two month duration. The control group subjects were matched to insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group using the characteristics of age, sex, occupation, economic status, and type of social life.

Exclusion criterion consisted of the presence of a physical or mental disability. Ten expert members of our faculty studied and verified the validity of each tool and the overall content validity of the questionnaire after it had been translated from English to Persian, and the results were translated back into English. The reliability of the questionnaire was calculated using a test-retest method asking ten people in the study population to complete the questionnaire a second time, four days after the initial trial. The results of both tests were then compared and, because they differed by only 10%, the questionnaire was verified to be reliable and was used to analyze the objectives and hypothesis of the study. It must be mentioned that reliability of the questionnaire was calculated using Hanestad and Albrektsen [12] and Alpha Cronbach methods that resulted in a coefficient of reliability of 0.9.

Ethical issues

We began the study after obtaining permission from the Morality Committee of the Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery of Isfahan. The study commenced at the Diabetes Research, Education and Treatment Center in Isfahan, and the samples were collected after fully explaining the nature of the study and obtaining written consent from all participants. Control group participants were from the city of Isfahan and were chosen from healthy people with no chronic disease or disability and that were of similar age and economic and social status to the experimental group.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive indices such as frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation (SD) were used to express the data. The Wilcoxon test was applied to determine the presence of any significant difference in scores obtained in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus and control groups. All analyses were performed using SPSS software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

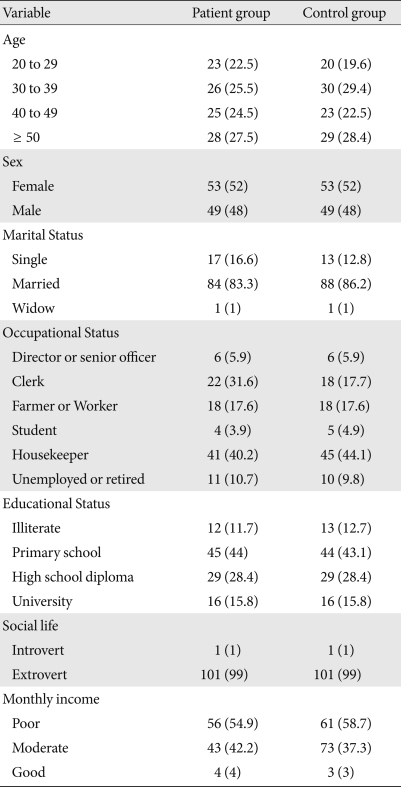

The mean participant age in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group was 50.5±11.7 years, while that in the control group was 40.7±11.6 years. Fifty-two percent of the total responders were female. Most people in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group (83.3%) and in the control group (86.2%) were married. Most people in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group (40.2%) and most people in the control group (44.1%) were homemakers. Overall, 23.5% of the responders had a high school diploma. Most of the participants in both groups (99%) were living with other people, such as their father, mother, spouse, children, sisters, brothers, or other extended family. The reported income level was average in 24.5% of the patients and 28.4% of the control group. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the insulin-dependent with diabetes mellitus subjects and the healthy control group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of insulin-dependent subjects and healthy responders

Data are presented as number (%).

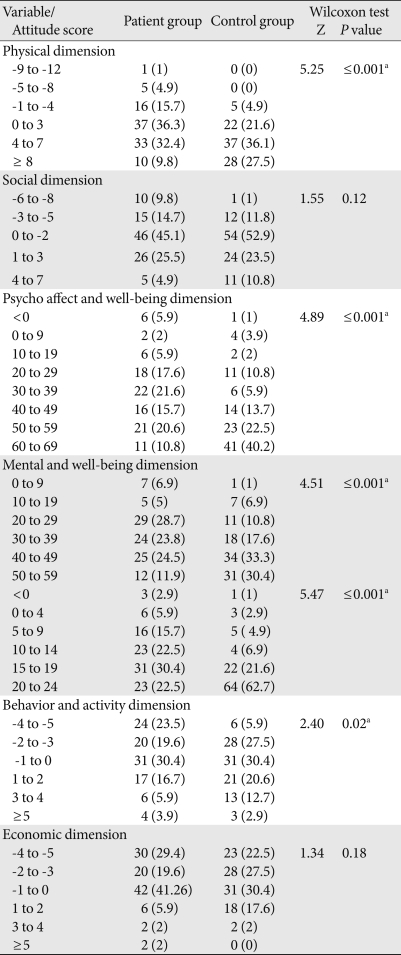

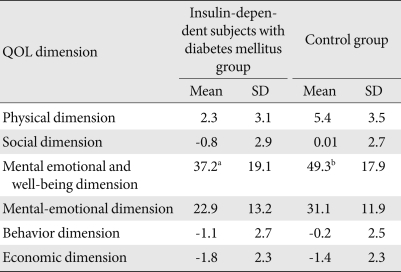

The mean total score for attitude toward QOL was 53.8 in the control group and 35.9 in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group. Using the Wilcoxon test with a 95% confidence interval revealed a significant difference in the attitude toward QOL scores between the two groups (Z=5.37, P≤0.001). The Wilcoxon test also revealed that there were significant differences between the two groups regarding the physical dimension (P≤0.001), the mental-emotional and feelings of well-being dimension (P≤0.001), and the behavioral-activity dimension (P≤0.02). However, no significant differences were observed with respect to the social and economic dimensions (P=0.18) (Table 2). A review of the total scores showed that the highest total score was reported for the mental-emotional and feelings of well-being dimension in both groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

A comparison of attitude scores between the case and control groups

Data are presented as number (%).

aSignificant relationship.

Table 3.

Comparison of attitude toward quality of life (QOL) score between the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus and control groups

SD, standard deviation.

aThe highest total score in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group was for the mental-emotional and well-being dimension, bThe highest total score in the control group was for the mental-emotional and well-being dimension.

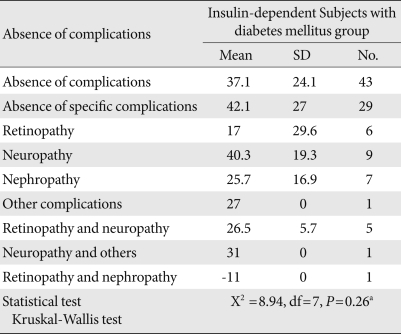

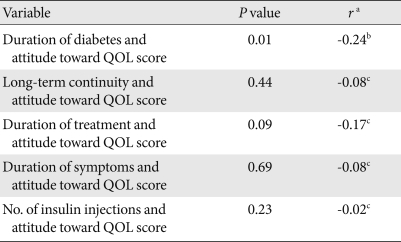

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed no correlation between insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus complications and mean score of attitude toward QOL (χ2=8.94, df=7, P=0.26) (Table 4). The Spearman test revealed that there was a significant difference only between the duration of diabetes and the total score of attitude toward QOL in the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus (r=0.24, P<0.01) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus complications and mean attitude toward quality of life (QOL) score

SD, standard deviation.

aNo significant difference.

Table 5.

Correlations between attitude toward quality of life (QOL) score and variables

aSpearman correlation, bSignificant inverse relationship, cNo significant relationship.

DISCUSSION

We found that the mean total scores of attitudes toward all dimensions of QOL were higher in the control group (healthy people) than in the insulin-dependent Subjects with diabetes mellitus group. These findings are similar to the results reported by Dehghanzadeh [13], Dahkordi et al. [14], and Redkop et al. [15] in their QOL studies, as well as those of Davis et al. [16], who studied QOL in Insulin-dependent Subjects with diabetes mellitus subjects. Previous researchers have mentioned that total QOL scores in healthy people are greater than those affected by type 1 diabetes mellitus. Davis et al. [16] noted that insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus can affect attitude toward QOL and result in a decreased attitude assessment score.

The mean scores for attitude toward the physical dimension of QOL were significantly different between the two groups, with the control group scoring higher than the insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus group. This finding is similar to that of a study by Dehghanzadeh [13]. Since insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus subjects suffer from various disease-related physical problems and limitations, these effects can influence attitudes toward physical abilities [17]. Rubin and Peyrot [18] and Wexler et al. [19] have also reported that insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus tend to have poor attitudes toward QOL than do healthy people, particularly regarding physical performance. It is believed that negative attitudes toward physical ability and QOL in people with insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus may be related to their feelings and concerns regarding disease prognosis.

Mean scores for the mental-emotional and feelings of well-being dimension were also significantly different between the two groups. This finding is similar to that of a study by Lindovist and Sjoden [20]. Hart et al. [21] also stated that attitudes toward QOL in insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus are lower in the mental-emotional dimension than are those of healthy subjects. Stress due to chronic disease, a continuous demand for self-care, and the possibility of developing additional conditions resulting from the disease can all result in mood disorders, such as anxiety and depression, in patients affected by insulin-dependent subjects with diabetes mellitus [22]. The behavioral-activity dimension scores were also significantly different between the two groups (P≤0.016). This result is similar to those of Lindqvist and Sjoden [20] and Dehghanzadeh [13]. Deyo [23] stated that the pain resulting from disease can cause changes in the behavior, activity-related disorders, and insomnia.

No significant differences between the groups were noted in the social or economic dimensions, which is contrary to findings reported by Axelsson et al. [24], who reported that positive attitudes toward occupational life may increase QOL score.

We found a significant relationship between duration of diabetes and the total attitude toward QOL score. This result is similar to that of a study by Martinez et al. [25]. In addition, Martinez et al. [25] found that attitude toward quality of life decreases as duration of diabetes increases.

Our results demonstrate that mean total scores for attitude toward QOL and some of its dimensions (physical, mental, emotional and feelings of well-being, and behavioral-activity) were higher in healthy control group than they were in insulin-dependent people with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Since attitude toward QOL is an index of individual and social health, it seems that the latter group needs education and psychological counseling, particularly in the areas of mental-emotional health and feelings of well-being, as well as those of activity, exercise, and employment. We recommend that health care teams take the necessary actions to establish encouraging relationships with these subjects, provide health education that uses state of the art technology, form support groups that include family members, and help patients find financial support opportunities through government assistance. We also recommend further study on how members of a health care team can best help improve the attitude toward QOL in insulin-dependent subjects with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all personnel at the Diabetes Research, Education and Treatment Center of Isfahan, as well as the study participants, for their great assistance. Also, we would like to thank the Farzan Institute for Research and Technology for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Epidemiology of diabetes. [cited 2009 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/en/

- 2.Ekoe JM, Rewers M, Williams R, Zimmet P. The epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. 2nd ed. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. Chapter 17, The epidemiology of diabetes in pacific island populations; pp. 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization: Health situation and trend. [cited 2009 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/countries/2008/sma/health_situation.htm.

- 4.Department of Health, Treatment, and Medical Education. Reports of diabetes and epidemiological. Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; 1995. pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis TM, Clifford RM, Davis WA Fremantle Diabetes Study. Effect of insulin therapy on quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;52:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes AA, Bragg-Gresham JL, Satayathum S, McCullough K, Pifer T, Goodkin DA, Mapes DL, Young EW, Wolfe RA, Held PJ, Port FK Worldwide Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Committee. Health-related quality of life and associated outcomes among hemodialysis patients of different ethnicities in the United States: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:605–615. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanbari A, Yekta P, Atrkar Roushan Z. Determine of the pattern of effective factors on quality of life in diabetic patients. J Guilan Univ Med Sci. 2001;10:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SC, Kuo PW, Wang JD, Lin MI, Su S. Quality of life and its determinants of hemodialysis patients in Taiwan measured with WHOQOL-BREF (TW) Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:635–641. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Eisele G, Burrows-Hudson S, Messana JM, Levin N, Rajagopalan S, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Saran R. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:658–666. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanestad BR, Albrektsen G. Quality of life, perceived difficulties in adherence to a diabetes regimen, and blood glucose control. Diabet Med. 1991;8:759–764. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1991.tb01696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurz X, Scuvee-Moreau J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Dresse A. Cognitive impairment, dementia and quality of life in patients and caregivers. Acta Neurol Belg. 2003;103:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanestad BR, Albrektsen G. Self-reported impact of insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in daily life and quality of life experience. Scand J Caring Sci. 1992;6:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dehghanzadeh SH. Comparison of quality of life in congestive heart failure patients and normal individuals; Paper presented at: 14th Congress of Iranian Heart Association in collaboration with British Cardiac Society; 2004 Nov 23-6; Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dehkordi A, Heydarnejad MS, Fatehi D. Quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Oman Med J. 2009;24:204–207. doi: 10.5001/omj.2009.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redekop WK, Koopmanschap MA, Stolk RP, Rutten GE, Wolffenbuttel BH, Niessen LW. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Dutch patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:458–463. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis WK, Hess GE, Harrison RV, Hiss RG. Psychosocial adjustment to and control of diabetes mellitus: differences by disease type and treatment. Health Psychol. 1987;6:1–14. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.6.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanestad BR, Albrektsen G. The stability of quality of life experience in people with type 1 diabetes over a period of a year. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:777–784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 1999;15:205–218. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-7560(199905/06)15:3<205::aid-dmrr29>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wexler DJ, Grant RW, Wittenberg E, Bosch JL, Cagliero E, Delahanty L, Blais MA, Meigs JB. Correlates of health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1489–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindqvist R, Sjoden PO. Coping strategies and quality of life among patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:312–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart HE, Redekop WK, Assink JH, Meyboom-de Jong B, Bilo HJ. Health-related quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1319–1320. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayry M. Measuring the quality of life: why, how and what? Theor Med. 1991;12:97–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00489791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA. The quality of life, research, and care. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:695–697. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-8-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Axelsson L, Andersson I, Hakansson A, Ejlertsson G. Work ethics and general work attitudes in adolescents are related to quality of life, sense of coherence and subjective health-a Swedish questionnaire study. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez YV, Prado-Aguilar CA, Rascon-Pacheco RA, Valdivia-Martinez JJ. Quality of life associated with treatment adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:164. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]