Abstract

The development of bladder and bowel neuroprostheses may benefit from the use of sensory feedback. We evaluated the use of high-density penetrating microelectrode arrays in sacral dorsal root ganglia (DRG) for recording bladder and perineal afferent activity. Arrays were inserted in S1 and S2 DRG in three anesthetized cats. Neural signals were recorded while the bladder volume was modulated and mechanical stimuli were applied to the perineal region. In two experiments, 48 units were observed that tracked bladder pressure with their firing rates (79% from S2). At least 50 additional units in each of the three experiments (274 total; 60% from S2), had a significant change in their firing rates during one or more perineal stimulation trials. This study shows the feasibility of obtaining bladder-state information and other feedback signals from the pelvic region with a sacral DRG electrode interface located in a single level. This natural source of feedback would be valuable for providing closed-loop control of bladder or other pelvic neuroprostheses.

1. Introduction

Pelvic and pudendal nerves carry sensory signals to the lumbosacral spinal cord conveying information about the state of the bladder, urethra and perineal region [1,2]. These feedback signals may be useful for providing spinal cord injured patients information about the fullness of their bladder or in closed-loop bladder and bowel neuroprostheses [3], a feature that is currently not available.

Single unit activity from individual pelvic, pudendal and sacral root afferent fibers have been recorded in cats and show a high correlation to bladder pressure [4–7] as well as urethra, colon and rectal activity [4,8,9]. While these studies provided insight into the pathways involved with signal transduction in the pelvic region, their approach of using wire or hook electrodes to record from individually separated axons is not readily translatable to neuroprosthetic applications.

More recently, researchers have shown the ability to detect bladder contractions from cuffs placed around entire sacral roots [10] and the pudendal nerve [11] in cats. Intraoperative human evaluations with nerve cuffs on sacral roots have also suggested an ability to detect bladder contractions [12]. These results had low signal-to-noise ratios and were unable to clearly differentiate non-bladder activity or estimate the bladder volume. Other cuff electrode approaches have suggested an ability to track the bladder pressure [13,14], however they may also be susceptible to interference from non-bladder afferent activity.

An alternate approach for accessing these afferent signals is to implant microelectrodes in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) where sensory fibers are separated from motor fibers and converge en route to the spinal cord. The DRG contain the primary afferent neuronal somata, which are large (20 – 150 μm) [15], facilitating recording of large amplitude action potentials [16,17]. High density microelectrode arrays in the lumbar DRG have been shown to provide high quality recordings of single unit activity from large populations for hind limb afferents in both acute [18,19] and chronic [20] implant scenarios. These studies demonstrated the ability to accurately estimate the multi-dimensional state of the lower limb from the activity of a small population of afferent units [18–21]. A similar approach may be suitable for obtaining bladder and perineal sensory information.

The primary objective of this study was to identify and record neural activity from bladder afferents within sacral DRG using penetrating microelectrode arrays. The secondary goal was to identify and record from primary afferent units from other sources within the pelvic and perineal region. Both objectives were achieved as neural recordings were obtained from numerous units that responded to specific stimuli, demonstrating the feasibility of this approach.

2. Methods

2.1 Experimental Setup

Three intact, adult male cats were used in this study, with all procedures approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Each animal was initially sedated with ketamine (10–15 mg/kg) before continuous anesthesia with isoflurane (1.5–2.5%). Subsequent anesthesia maintenance varied between each experiment. In the first experiment, after completion of all surgical steps, the animal was transitioned to α-chloralose (70 mg/kg initial dose; 20 mg/kg maintenance doses) augmented with low levels of isoflurane (0.1–0.7%). The second animal was decerebrated by transecting the brainstem anterior to the superior colliculus at a 50 degree angle to the horizontal, and isoflurane remained on at 1–1.3% for the remainder of the experiment. The third experiment was transitioned completely to α-chloralose after completion of all surgical steps (70 mg/kg initial dose; 20 mg/kg maintenance doses, augmented with bupernex 0.01 mg/kg every 12 hr) without isoflurane. Variations in the anesthetic regimen are not expected to affect the sensitivity of the mechanoreceptive afferents examined in this study as they do not receive efferent inputs.

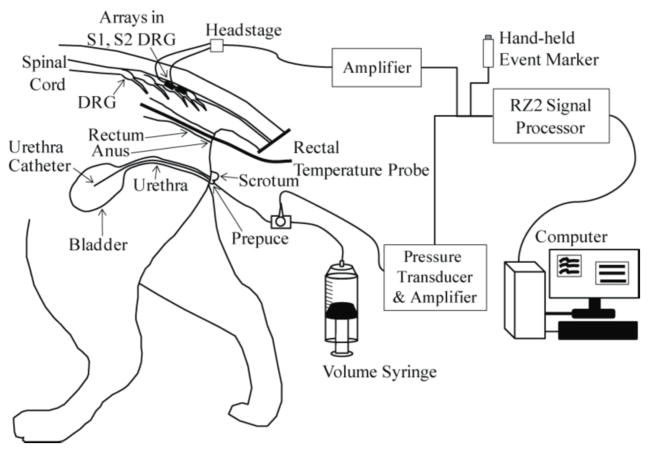

After induction of anesthesia, a tracheotomy was performed and the animal was connected to a ventilator. Vitals were monitored and maintained within normal physiological ranges. An intravenous line was inserted in one or both forelimbs for fluid infusion. A polypropylene catheter (3.5 Fr, Sovereign) was inserted intraurethrally to the bladder for controlling the bladder volume and measuring the bladder pressure (figure 1). A stop cock on the end of the urethra catheter was used to select pressure monitoring or volume control. A saline-filled tube for pressure monitoring was connected to a pressure transducer (DTXPlus DT-4812, Beckton Dickinson) and transducer amplifier (TA-100, CWE). Bladder volume control was performed with a refillable syringe connected to the other output of the stop cock. A laminectomy was performed to expose the S1–S2 sacral dorsal root ganglia. The cat was positioned in a custom-built frame with the torso and pelvis suspended. Penetrating microelectrode arrays (90 channels: 4×10 and 5×10 ICS-96 MultiPort split planar arrays, 1 mm shaft length, 0.4 mm interelectrode spacing, Blackrock Microsystems) were inserted in the S1 and S2 DRG of each cat with a pneumatic inserter (Blackrock). In the first and second cat, the electrode tips were coated with sputtered iridium oxide and had average impedances of 46.9 ± 5.3 kΩ. In the third cat the electrode tips were coated in platinum and had average impedances of 227.3 ± 91.2 kΩ. In the first cat, the 5×10 array was inserted in S1 and the 4×10 array was inserted in S2. In the second and third cats the arrays were switched. Neural data from the microelectrode arrays as well as the analog bladder pressure were recorded using a biopotential processor for data sampling and storage (RZ2, TDT). Neural signals were sampled at 25 kHz and bandpass filtered (300–3000 Hz) before online thresholding to generate spike snippets, which were stored for offline analysis. The bladder pressure signal was captured at 100 Hz.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup. A urethral catheter was inserted for access to the bladder for fluid infusion and pressure monitoring. A 90-channel microelectrode array (Blackrock ICS-96 MultiPort split array: 50 and 40 electrodes) was inserted in the S1 and S2 DRG on one side. Sensory stimuli were applied by changing the bladder volume, moving the urethra catheter, pinching the prepuce, brushing the scrotum, moving the rectal temperature probe and brushing around the anus. Neural signals from the microelectrodes and the bladder pressure were viewed and stored on a PC after processing with a TDT RZ2 system.

2.2 Experimental Protocol

In the second and third experiments, neural activity was recorded at incremental constant bladder volumes. First, the bladder was emptied via the urethral catheter. Next, one-minute long constant bladder volume trials were conducted starting at 0 mL, and continued at 5–10 mL increments until there was leakage of the infused saline around the urethra catheter,. Recording commenced in each trial after the bladder pressure had settled following an infusion of saline.

Several perineal mechanical stimulation trials were performed in all three experiments: 0.5–1.5 mm shifts in the position of the urethra catheter and rectal temperature probe, light brushing around the anus with a q-tip, and pinching of the prepuce. In the second and third experiments, light brushing of the scrotum with a q-tip was also performed. The time of application for each sensory stimulus was recorded with a hand-held trigger button that generated an event marker in the TDT system.

After completion of all experimental objectives, the animals were euthanized. The first two animals were given an intravenous dose of potassium chloride (10 mL of 2 mEq/mL) while deeply anesthetized. The third animal was deeply anesthetized with an intravenous dose of ketamine (15 mg/kg) before transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde towards histological analyses related to other experimental objectives.

2.3 Data Analysis

Offline analyses were performed to identify neural units that responded to each sensory stimulus. Spikes were sorted in OpenSorter (TDT) using a two stage process: a k-means algorithm was first used to generate initial spike clusters and then each channel was reviewed and manually sorted further, if necessary, to obtain only units that could be consistently differentiated across all trials run in an experiment.. In the two experiments with fixed bladder volume trials, the average number of spikes per second for each unit and the average bladder pressure was calculated in Matlab for each bladder volume trial. Units identified during the spike sorting process were designated as ‘bladder units’ using criteria established in previous studies of recordings from individual pelvic nerve and sacral root filaments. These criteria include units where spiking was absent when the bladder was empty and that had an approximately linear increase in firing rate at increasing bladder pressures. Bladder afferents have been shown to have maximum firing rates below 20 spikes per second for bladder pressures below 50 cm H2O [4,5,7]. A similar approach was followed in the third experiment, using several short 10–15 s periods of constant bladder pressure.

For the perineal stimulus methods, a different analysis approach was followed, since these stimuli were in one of two states (on, off). Spike counts in one-second bins were used to estimate the “stimulus on” spike rate per unit, for each trial. For non-continuous stimuli (urethra catheter and rectal probe movement), 0.5-seconds on either side of each event marker were used. For continuous stimuli (anus brushing, prepuce pinching, scrotum brushing), contiguous one-second intervals, starting one second after and ending one second before start/stop event markers were used. Spike counts during a corresponding number of one-second bins when no stimulus was being applied were also counted, to estimate the “stimulus off” spike rate. At least 20 bins were used for both “stimulus on” and “stimulus off” periods for each trial, with additional bins used when available from both periods. The stimulus on and off estimated spike rates for all units within a given trial were compared for significant difference using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The significance level (α < 0.05) was adjusted according to the Bonferroni correction, to account for multiple comparisons (i.e. multiple neurons were tested) within each trial. This typically resulted in significant p-values less than 0.0005 when identifying units that responded to each stimulus type. Values for a particular result are given as the average ± standard deviation.

3. Results

In all experiments, DRG units were identified that responded to one or more pelvic stimuli. Across the three experiments, 290 units (114 on S1; 176 on S2) were identified that responded to one or more stimuli, including many units that responded to multiple stimuli (71%). Table 1 provides a summary by experiment and trial type of the number of responding units. Also identified were 69 units (43 on S1; 26 on S2) that did not show a significant response to any applied stimuli. The results from each cat were obtained during an approximately two-hour period at the end of each experiment. No differences in the amplitudes or firing rates of individual units were observed in this time.

Table 1.

Number of electrode channels (in parentheses - number of units) responding to each stimulus trial, for each DRG and experiment. S1 had 50 electrodes in Cat 1 and 40 electrodes in Cats 2 and 3. S2 had 40 electrodes in Cat 1 and 50 electrodes in Cats 2 and 3.

| Trial | Cat 1 | Cat 2 | Cat 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | S1 | S2 | |

| Urethra Catheter | 9 (11) | 10 (21) | 8 (9) | 5 (8) | 9 (15) | 28 (52) |

| Prepuce Pinch | 24 (30) | 19 (62) | 15 (22) | 10 (16) | 18 (33) | 32 (78) |

| Scrotum Brush | Not Tested | 5 (6) | 6 (9) | 16 (27) | 32 (75) | |

| Rectal Probe | 7 (15) | 10 (13) | 7 (8) | 10 (21) | 13 (18) | 29 (61) |

| Anus Brush | 14 (25) | 19 (44) | 5 (6) | 9 (12) | 13 (20) | 32 (69) |

| Bladder Pressure | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 9 (12) | 6 (7) | 25 (26) |

3.1 Bladder Units

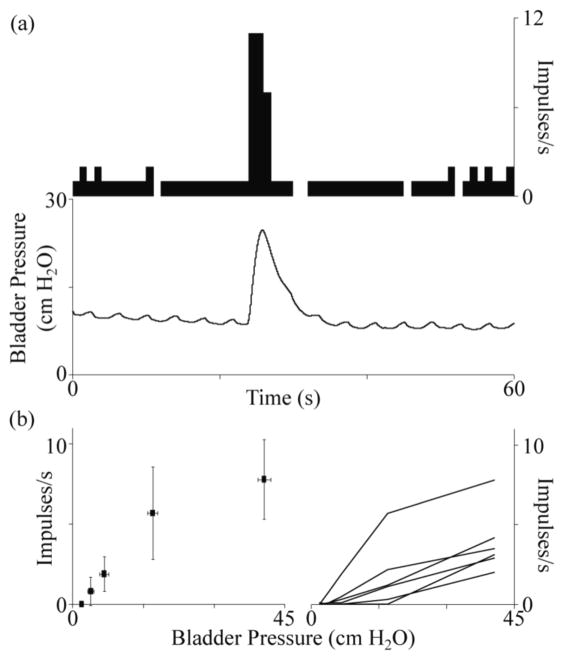

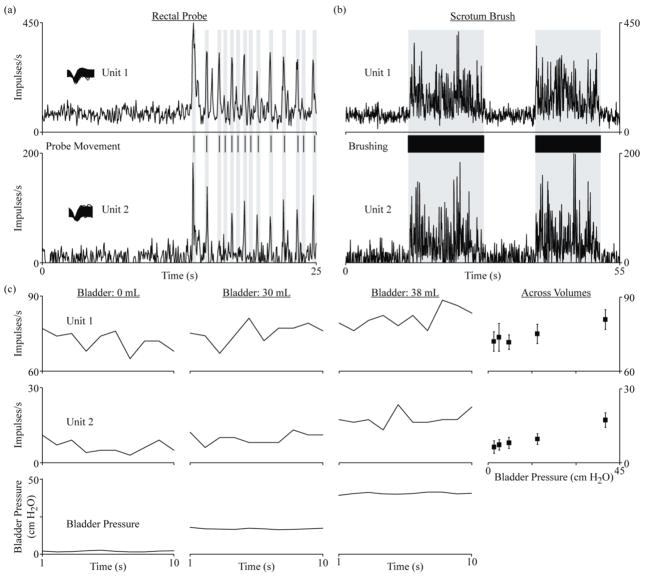

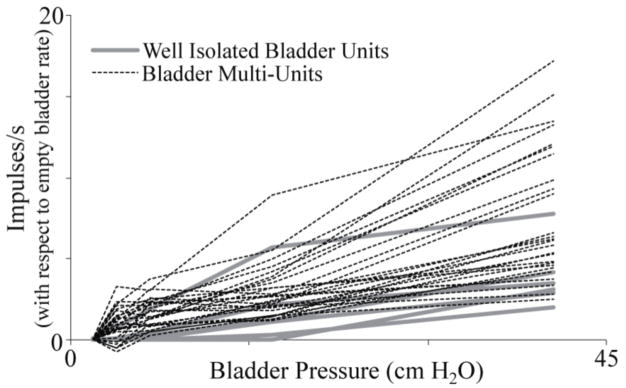

In the two experiments that included extensive tests of bladder volume, eleven (cat 2) and thirty-one (cat 3) channels had units that were linearly related to bladder pressure (table 1). Six units in each of these experiments (10 of 12 on S2) were well-isolated units that were quiet at low bladder pressures and fired more frequently at higher bladder pressures (figure 2). An additional thirty-six units (28 on S2) were identified that responded to bladder pressure changes but had non-zero firing rates at low bladder pressures (figure 3). Thirty-two of these “multi-units” also responded to one or more of the other applied stimuli and could not be separated into bladder-responding and non-bladder-responding units. When the firing rates of these multi-units at an empty bladder volume were subtracted from the firing rates at other volumes, they had similar response characteristics to the well-isolated units that responded to changes in bladder volume (figure 4). In the experiment that did not have fixed bladder volume tests (Cat 1), only one bladder multi-unit was identified. Other bladder units may have been present within the recordings but were not apparent due to the lack of extended constant bladder volume trials.

Figure 2.

Relationship between firing rate and bladder pressure for well-isolated bladder units. In (a), an example unit from Cat 2 is shown at a bladder volume of 20 mL, with a baseline firing rate of about 1 spike per second except for a burst of spikes during a distension evoked contraction. The small oscillations in the bladder pressure are due to movement of the abdomen as the diaphragm expanded with each breath. In (b) the average firing rate for a single bladder unit, at 5 bladder volumes (left), and all bladder units (n = 6) from the same experiment (Cat 3; right) are shown.

Figure 3.

Examples of multi-unit bladder afferent activity responsive to bladder pressure changes and perineal stimulation. Two S2 units from Cat 3 are shown for (a) movement of the rectal probe, (b) brushing of the scrotum and (c) different bladder volumes. In (a) and (b), the instantaneous firing rate was calculated at 50 ms intervals by filtering the spike impulses with a linear filter [20], to provide a greater temporal resolution of the maximum spike rates attained. In (c), spike counts and bladder pressures for one-second bins are given for three bladder volumes. At the right, average spikes per bin are shown at five different bladder pressures corresponding to 0, 10, 20, 30 and 38 mL.

Figure 4.

Changes in bladder unit firing rates against bladder pressure. The average firing rates for each multi-unit at an empty bladder volume were subtracted from the average rates at other volumes. The response characteristics of many of the bladder multi-units (dashed line) were similar to the firing rate changes exhibited by well-isolated bladder units (thick grey lines), with some multi-units having a wider dynamic range. These units are from Cat 3.

Across all bladder units, the minimum pressure at which the firing rate was observed to increase by at least one spike per second from the baseline pressure was 11.5 ± 8.6 cm H2O (range: 3.8–40.6). Ninety-two percent of the observed bladder units first increased their firing rates at pressures below 20 cm H2O.

3.2 Non-Bladder Units

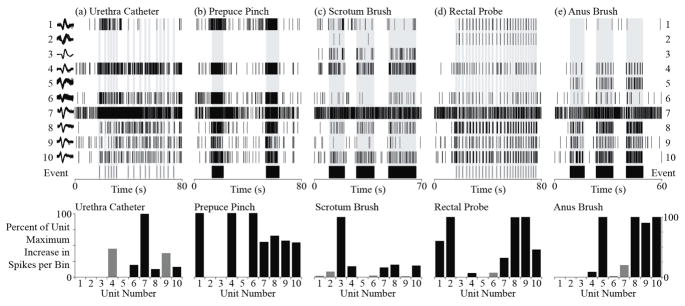

Across the three experiments, 274 DRG units had significant changes in their firing rates during one or more applied non-bladder stimuli (110 on S1, 164 on S2; figure 5). Seventy-one (24% of total unit count) of these units responded to a single non-bladder stimulus. See table 2 for a breakdown of these single-trial units by type.

Figure 5.

Examples of DRG units responsive to different perineal stimuli. At the top, raster plots for ten units (1–10, top to bottom) and the corresponding event markers are shown for (a) movements of the urethral catheter, (b) pinching of the prepuce, (c) brushing of the scrotum, (d) movement of the rectal probe and (e) brushing of the anus. Some units were clearly associated with more than one stimuli (units 1, 4, 6–10) while other units responded only to a single test (units 2, 3, 5). At the bottom, the increase in spike rate during each trial is normalized to the maximum value across trials for each unit. Black bars indicate units with significantly greater spike counts during the stimulus, according to a Wilcoxon rank-sum test with a Bonferroni correction (p < 0.0005), for each trial. Grey bars indicate units with non-significant increases in spike counts for that trial. Units 1–5 were from S2 while units 6–10 were from S1 in Cat 2.

Table 2.

Breakdown of seventy-one units across Cats 1, 2, and 3 that responded to a single non-bladder stimulus, by root.

| Trial | Root Count | Change in Firing Rate (sp/s) | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | Average | Range | ||

| Urethra Catheter | 3 | 2 | 7.7 ± 5.2 | 1.1 – 15.3 | |

| Prepuce Pinch | 28 | 15 | 7.6 ± 12.8 | −12.3 – 75.3 | |

| Scrotum Brush | 0 | 4 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 1.5 – 3.8 | figure 6 - unit 3 |

| Rectal Probe | 3 | 9 | 1.6 ± 3.6 | −8.1 – 6.3 | figure 6 - unit 2 |

| Anus Brush | 1 | 6 | 5.8 ± 4.3 | 1.1 – 12.4 | figure 6 - unit 5 |

The most frequently observed DRG units were non-specific and had significant changes in their firing rates during more than one stimulus. Fifty units (17%) responded to all non-bladder stimuli (33 on S2; figure 5 - units 8 & 10). Nineteen of the thirty-six bladder multi-units responded to bladder pressure and all non-bladder stimuli (17 on S2; figure 3). See table 3 for the average and range of firing rate increases for units that responded to all non-bladder stimuli. In addition to units that responded to all perineal stimuli, 105 units (36%) responded to two or more trials spanning the anal and genital regions (65 on S2; figure 5 - units 1, 4, 7, 9).

Table 3.

Firing rate responses per trial type for sixty-nine units across Cats 1, 2, and 3 that responded to all non-bladder stimuli. Average firing rates during Prepuce Pinch and Scrotum Brush were each significantly different (p < 0.05) from all other trials.

| Trial | Firing Rate Increase (sp/s) | |

|---|---|---|

| Average | Range | |

| Urethra Catheter | 16.3 ± 11.9 | 0.8 – 51.6 |

| Prepuce Pinch | 60.5 ± 54.4 | 4.2 – 238.0 |

| Scrotum Brush | 31.9 ± 24.7 | 1.5 – 111.8 |

| Rectal Probe | 16.3 ± 17.4 | 1.6 – 96.9 |

| Anus Brush | 23.4 ± 34.5 | 0.9 – 229.7 |

Some DRG units that responded to more than one trial had smaller receptive fields. Twenty-five units (13 on S1) responded to two or three of the trials involving urethral catheter movement, brushing of the scrotum and pinching of the prepuce (figure 5 - unit 6). Four units (3 on S2) responded to only movement of the rectal probe and brushing of the anus.

3.3 Non-Perineal Units

Sixty-nine DRG units were identified that did not have significantly different spike rates during any applied stimuli. Among these were eighteen units (12 on S1) that were likely perineal units, having at least one stimulus test with a p-value < 0.05, however their change in estimated spike rate was not significant after the Bonferroni correction. Among the remaining non-perineal units, three (2 on S1) were cutaneous or visceral afferent units that had cyclic firing rates, which directly tracked the respiratory rate of about 12 breaths per minute. Several more of these cyclic units also responded to one or more applied sensory stimuli and were included in those totals. Also observed were 25 units (21 on S1) which had fairly constant firing rates, ranging from ~1 spike every second up to ~50 spikes every second, that were not affected by any applied stimuli. These may have been cutaneous units with receptive fields in direct contact with the support frame or muscle spindle type II afferents. Twenty-three remaining non-perineal units (17 on S1) did not have any unique or identifying characteristics.

4. Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the feasibility of recording from sacral primary afferents with receptive fields in the pelvic region using a multielectrode array in the DRG. In three experiments, we observed 48 units that were correlated to bladder pressure and 274 units that responded to one or more applied perineal stimuli. In general, the majority of bladder units were found at the S2 level while slightly greater numbers of non-bladder units, responsive to all stimuli, were found on S2 than S1. As the pelvic organs have bilateral innervation, these results suggest that a single microelectrode array in a single DRG (S2 in cat) may be sufficient to record afferent activity from the bladder, genitalia and rectum.

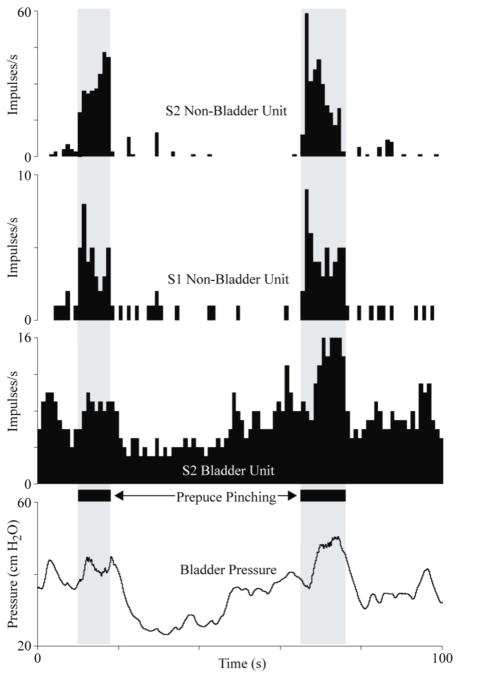

The responses in these experiments were similar to neural recordings from individual pelvic and sacral root axons under comparable test conditions [4–7]. Bladder afferents increased their firing rate from zero when the bladder was empty to 3–20 spikes per second at higher bladder pressures (figures 2, 4 and 6). The bladder pressure during these tests were comparable to normal physiological levels [5]. Bladder pressures leading to an increase of at least 1 spike per second varied between 4 and 41 cm H2O, with most of the units first responding below 20 cm H2O. This range is in agreement with studies reporting threshold ranges of 7–20 cm H2O when recording directly from pelvic nerves or sacral roots [4,5,7]. Bladder afferent firing rates tracked changes in bladder pressure (figures 2(a), 3(c) and 6) in a linear manner (figures 2(b) and 4), and could be used to differentiate between bladder and non-bladder activity (figure 6).

Figure 6.

An example showing how multielectrode array recordings from the sacral DRG can monitor complex pelvic activity such as this continence reflex, where reductions in bladder pressure were evoked by manual stimulation of genital nerves in the penis. The non-bladder DRG units responded only to the pinching of the prepuce while the bladder unit modulated its firing rate in response to bladder pressure fluctuations. Unit firing rates are given as spike counts per 1-second interval. These units are from Cat 2.

We observed bursts of action potentials for each type of perineal stimulation (figures 3, 5 and 6). These changes in firing rates were usually clear, as 93% of the 69 units responding to all perineal stimuli had a spike rate increase of at least 10 spikes per second in one or more trials and 30% increased at least 10 spikes per second in all trials (example in figure 3(a)). Similar changes in afferent firing rates have been reported when recording from individual pelvic [4] and pudendal [9] axons during the same types of stimuli. Some lumbosacral DRG afferents are dichotomizing afferents that innervate more than one pelvic organ [22–24]. In addition to recording from these multi-organ afferents, it is likely that DRG units responding to multiple stimuli included perineal cutaneous units that had large receptive fields that were activated in some manner during each of the different trials. Among these multi-responsive units, pinching the prepuce and brushing the scrotum led to significantly greater spike rate responses than other stimuli (table 3). The tip of the penis, squeezed during pinching of the prepuce, has a high concentration of afferent fibers [25], which may have contributed to the higher spike rates. Further studies evaluating conduction velocities and anatomical specificity would be useful in verifying the type and source(s) of each DRG unit.

As demonstrated here, DRG recordings provide an opportunity for probing the neurophysiology of the lower urinary tract and other pelvic functions. Microelectrode arrays inserted in DRG provide access to hundreds of units at a location where primary afferent fibers converge upon the spinal cord. Studies that looked at the responses of individual sacral afferents with cuff or hook electrodes were limited to recording from only a few units per experiment [4,5], a much lower efficiency that is possible with a DRG microelectrode approach. Recordings from the sacral DRG could be the central focus of studies to gain further understanding of pelvic diseases and neurophysiology, such as investigating changes in the properties of DRG afferents after spinal cord injury [26], studying the mechanisms of afferent convergence at the DRG [22], and evaluating neural connections in cases of neurogenic lesions [27]. Chronic recording studies performed with microelectrode arrays implanted in the sacral DRG of awake, behaving cats, as has been done in lumbar DRG [19], would provide further insights without the influence of anesthesia and allow for evaluations of the stability of sacral DRG recordings, which has yet to be demonstrated.

An application of this DRG microelectrode approach is the development of neural prostheses integrating sensory feedback. Recordings from DRG bladder units could be used to regulate conditional genital nerve stimulation to inhibit the bladder when the bladder pressure gets high or as soon as contractions occur [10]. The use of high-density recordings that simultaneously track bladder and non-bladder units may yield a more accurate estimation of bladder activity than non-specific recordings from entire nerve fibers [10–12] that indicate only gross activity such as bladder contractions or are susceptible to interference from non-bladder activity. Sacral DRG units can be sorted to differentiate bladder activity from perineal activity (figure 6), reducing the occurrence of incorrect bladder contraction detections. DRG recordings from non-bladder units may be useful for determining when the colon is full, flow through the urethra is occurring or when there is undesirable cutaneous pressure or friction in the pelvic region. Dichotomozing afferent signals could be used to provide general state information on the entire pelvic region while individual-organ responsive units would provide finer resolution. A sacral DRG interface that tracks some of these sensations may be instrumental in defecation neural prostheses, bladder voiding neural prostheses, sexual function neural prostheses or for detecting the onset of pressure ulcers.

Although these microelectrode arrays penetrate neural tissue, the potential exists for recording from the surface of the sacral DRG. An electrode interface that does not penetrate neural tissue may have fewer undesirable tissue responses and may be easier to evaluate in human subjects. Cell bodies within the DRG are packed closely below the epineurium [28], suggesting that recording electrodes may not need to penetrate the DRG to record neural activity. We have recently demonstrated the feasibility of this approach and have recorded lumbar afferent activity that correlates to limb position and movement [29]. A similar approach at the sacral level may lead to a minimally invasive sacral DRG neural interface.

Several factors within this experiment may have led to an under-representation of the number of primary afferents that can be recorded with a penetrating microelectrode array. These tests were conducted at the end of experiments that evaluated other objectives with the lumbar DRG and used the same electrode arrays. Repeated use of these electrodes led to at least 30 non-functioning electrodes on the S2 array in Cat 2 and an unknown number of failures on the other arrays. Thus in each experiment we were recording from many fewer than 90 total electrodes. Also, the effect of an extended period under anesthesia for each cat, by the time these tests were performed, may have had a negative impact on the bladder or neural tissue. Furthermore, significance tests for each non-bladder unit may not have been accurate representations of the actual physiology as stimulus event markers were human-generated and the time counts of spikes were for 1-second intervals, a much lower resolution than at which the units actually respond to stimuli. Nonetheless, as suggested by figures 2, 3, 5 and 6, simple visual review was sufficient to identify the majority of afferent units.

5. Conclusions

This work is the first demonstration of bladder and perineal primary afferent recordings using microelectrode arrays implanted in the DRG. This approach may be beneficial for probing the neurophysiology of the pelvic organs and perineal region or for obtaining sensory signals for use in closed-loop control of bladder and bowel neuroprostheses. Future experiments will study the underlying physiology further and evaluate signals from the surface of sacral DRG.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Rehabilitation Neural Engineering Lab for their assistance during the animal experiments (Ingrid Albrecht, Tyler Simpson) and with data analysis (Chris Ayers, Jim Hokanson, Joost Wagenaar). This work was supported in part by NIH grants 1R01-EB007749 and 1R21-NS-056136 and TATRC grant W81XWH-07-1-0716.

Contributor Information

Tim M Bruns, Email: tmb59@pitt.edu.

Robert A Gaunt, Email: rag53@pitt.edu.

Douglas J Weber, Email: djw50@pitt.edu.

References

- 1.de Groat WC. Integrative control of the lower urinary tract: preclinical perspective. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:25–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vodusek D. Anatomy and neurocontrol of the pelvic floor. Digestion. 2004;69:87–92. doi: 10.1159/000077874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haugland M, Sinkjaer T. Interfacing the body’s own sensing receptors into neural prosthesis devices. Technol Health Care. 1999;7:393–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahns E, Halsband U, Janig W. Responses of sacral visceral afferents from the lower urinary tract, colon and anus to mechanical stimulation. Pflug Arch Eur J Phy. 1987;410:296–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00580280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habler H, Janig W, Koltzenburg M. Myelinated primary afferents of the sacral spinal cord responding to slow filling and distension of the cat urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1993;463:449–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iggo A. Tension receptors in the stomach and the urinary bladder. J Physiol. 1955;128:593–607. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1955.sp005327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winter D. Receptor characteristics and conduction velocities in bladder afferents. J Psychiatr Res. 1971;8:225–35. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(71)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todd J. Afferent impulses in the pudendal nerves of the cat. Exp Physiol. 1964;49:258–67. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1964.sp001730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cueva-Rolon R, Munoz-Martinez E, Delgado-Lezama R, Raya J. The cat pudendal nerve: afferent fibers responding to mechanical stimulation of the perineal skin, the vagina or the uterine cervix. Brain Res. 1994;655:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jezernik S, Grill WM, Sinkjaer T. Detection and inhibition of hyperreflexia-like bladder contractions in the cat by sacral nerve root recording and electrical stimulation. Neurourol Urodynam. 2001;20:215–30. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2001)20:2<215::aid-nau23>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenzel BJ, Boggs JW, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM. Detecting the onset of hyper-reflexive bladder contractions from the electrical activity of the pudendal nerve. IEEE T Neur Sys Reh. 2005;13:428–35. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.848355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurstjens GAM, Borau A, Rodriguez A, Rijkhoff NJM, Sinkjaer T. Intraoperative recordings of electroneurographic signals from cuff electrodes on extradural sacral roots in spinal cord injured patients. J Urol. 2005;174:1482–1487. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000173005.70269.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saleh A, Sawan M, Elzayat EA, Corcos J, Elhilali MM. Detection of the bladder volume from the neural afferent activities in dogs: experimental results. Neurol Res. 2008;30:28–35. doi: 10.1179/016164108X268250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jezernik S, Wen JG, Rijkhoff NJM, Djurhuus JC, Sinkjaer T. Analysis of bladder related nerve cuff electrode recordings from preganglionic pelvic nerve and sacral roots in pigs. J Urol. 2000;163:1309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devor M. Unexplained peculiarities of the dorsal root ganglion. Pain. 1999;6:S27–35. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prochazka A, Westerman RA, Ziccone SP. Discharges of single hind limb afferents in the freely moving cat. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:1090–1104. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.5.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeb GE, Bak MJ, Duysens J. Long-term unit recording from somatosensory neurons in the spinal ganglia of the freely walking cat. Science. 1977;197:1192–1194. doi: 10.1126/science.897663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoyagi Y, Pearson KG, Stein RB, Branner A, Normann RA. Capabilities of a penetrating microelectrode array for recording single units in dorsal root ganglia of the cat. J Neurosci Meth. 2003;128:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(03)00143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein RB, Weber DJ, Aoyagi Y, Prochazka A, Wagenaar J, Shoham S, Normann RA. Coding of position by simultaneously recorded sensory neurones in the cat dorsal root ganglion. J Physiol. 2004;560:883–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber DJ, Stein RB, Everaert DG, Prochazka A. Limb-state feedback from ensembles of simultaneously recorded dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neural Eng. 2007;4:S168–80. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/3/S04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber DJ, Stein RB, Everaert DG, Prochazka A. Decoding sensory feedback from firing rates of afferent ensembles recorded in cat dorsal root ganglia in normal locomotion. IEEE T Neur Sys Reh. 2006;14:240–3. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.875575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malykhina AP, Qin C, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Foreman RD, Lupu F, Akbarali HI. Hyperexcitability of convergent colon and bladder dorsal root ganglion neurons after colonic inflammation: mechanism for pelvic organ cross-talk. Neurogastroent Motil. 2006;18:936–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christianson JA, Liang R, Ustinova EE, Davis BM, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA. Convergence of bladder and colon sensory innervation occurs at the primary afferent level. Pain. 2007;128:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaban V, Chriseensen A, Wakamatsu M, McDonald M, Rapkin A, McDonald J, Micevych P. The same dorsal root ganglion neurons innervate uterus and colon in the rat. Neuroreport. 2007;18:209–12. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32801231bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson RD, Halata Z. Topography and ultrastructure of sensory nerve endings in the glans penis of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;312:299–310. doi: 10.1002/cne.903120212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Groat WC, Yoshimura N. Changes in afferent activity after spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodynam. 2010;29:63–76. doi: 10.1002/nau.20761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyndaele J. Investigating afferent nerve activity from the lower urinary tract: highlighting some basic research techniques and clinical evaluation methods. Neurourol Urodynam. 2010;29:56–62. doi: 10.1002/nau.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spencer PS, Raine CS, Wisniewski H. Axon diameter and myelin thickness - unusual relationships in dorsal root ganglia. Anat Rec. 1973;176:225–43. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091760209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaunt RA, Bruns TM, Crammond D, Tomycz N, Moossy JJ, Weber DJ. Single- and multi-unit activity recorded from the surface of the dorsal root ganglia with non-penetrating electrode arrays. 33rd Annual Intl. Conf. IEEE EMBS; Boston, MA, USA. 2011. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]