Abstract

Consumption of tomato products has been associated with decreased risks of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, and therefore the biological functions of tomato carotenoids like lycopene, phytoene and phytofluene are being investigated. In order to study the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of these carotenoids, a bioengineered Escherichia coli model was evaluated for laboratory-scale production of stable isotope-labeled carotenoids. Carotenoid biosynthetic genes from Enterobacter agglomerans were introduced into the BL21Star(DE3) strain to yield lycopene. Over 96% of accumulated lycopene was in the all-trans form, and the molecules were highly enriched with 13C by 13C-glucose dosing. In addition, error-prone PCR of phytoene desaturase (crtI) was used to create a phytoene-accumulating strain, which maintained the transcription of phytoene synthase (crtB), whereas crtI does not encode a functional phytoene desaturase because of introduced mutations. Phytoene molecules were also highly enriched with 13C when the 13C-glucose was the only carbon source. The development of this production model will provide carotenoid researchers a source of labeled tracer materials to further investigate the metabolism and biological functions of these carotenoids.

Keywords: Tomato, Lycopene, Phytoene, 13C, E. coli

Introduction

Tomato consumption has been correlated with decreased risks of chronic diseases including prostate cancer and cardiovascular disease 1. Among many nutrients and phytochemicals in fresh tomatoes and tomato products, carotenoids are thought to be the bioactive components responsible for disease prevention. Many epidemiological studies, clinical trials, animal studies, and in vitro studies have focused on the most abundant tomato carotenoid, lycopene 2. However, the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of phytoene and phytofluene, the precursors of lycopene and the 2nd- and the 3rd-most abundant tomato carotenoids, have not been fully studied.

As it is difficult to completely deplete the fat-soluble carotenoids from humans, stable isotope-labeled carotenoid tracers allow a single carotenoid dose to be followed within pre-existing, endogenous pools. Previously, labeled lutein, β-carotene or vitamin have been utilized to provide information regarding 1) the fraction of the ingested amount that is absorbed (bioavailability), 2) the fraction of that which is converted to vitamin A in the body (bioconversion), 3) the estimated body stores of vitamin A, and 4) the interaction between retinal and rhodopsin 3–8. To date, no tracer studies utilizing isotope-labeled phytoene or phytofluene have been conducted, either in animals or humans, and therefore very little is known regarding the ADME. Producing labeled phytoene and phytofluene has been a challenge to answer these important biomedical questions.

Currently, most of the commercially pure carotenoids are produced by chemical synthesis, whereas a few biotechnological production systems including microalgae, fungi, tomato cell culture and E. coli culture are being developed and optimized. Several concepts for the phototrophic mass culture of algae have been proposed and compared 9–11. Among many fungal strains, Blakeslea trispora has been employed for the production of natural lycopene, commercialized by Vitatene. In addition, cell suspension cultures of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. VFNT cherry) have also been developed for laboratory scale production of phytoene, phytofluene and lycopene in our laboratory 12. This system was further optimized by treating cells with two bleaching herbicides, 2-(4-chlorophenyl-thio)triethylamine (CPTA) and norflurazon and utilization of high carotenoid producing cell lines 13,14.

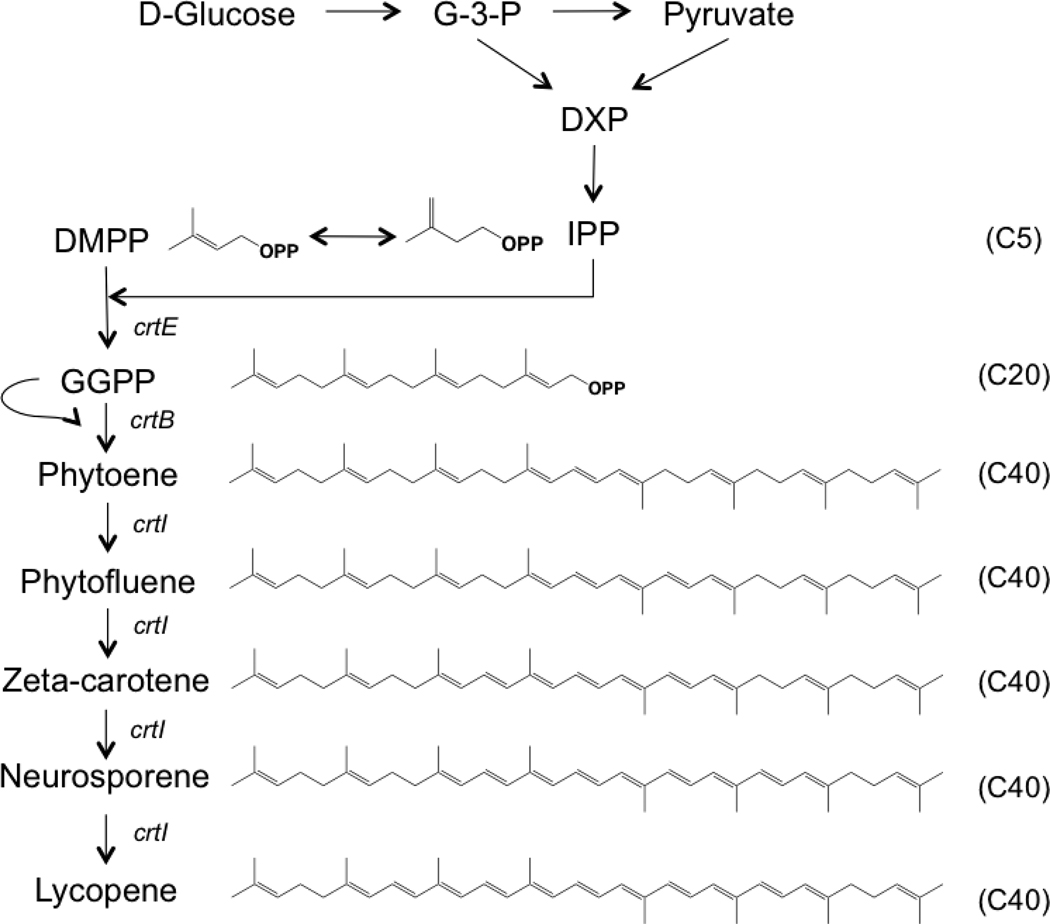

It has been well known that Escherichia coli harboring carotenogenic genes from a Gram-negative, non-photosynthetic bacterium, Enterobacter agglomerans (or Pantoea agglomerans, formally Erwinia herbicola), can accumulate carotenoids (Figure 1). This carotenogenic gene cluster was first cloned from E. agglomerans in 1986 15, and the DNA sequence was reported in 1990 16. Since then, novel carotenoids were produced in E. coli by combining different carotenoid biosynthetic genes from E. agglomerans and other species 17–20. Additionally, carotenoid production was tremendously improved by introducing the mevalonate pathway 21, increasing precursor supply 22 or by knocking out unnecessary genes in E. coli 23–25. Since E. coli can utilize glucose as the sole carbon source, and 13C-glucose is a readily available labeled source material, this system could be used to produce isotopically-labeled carotenoids. Therefore, the goal of this research was to utilize carotenoid-producing E. coli for producing stable isotope-labeled tomato carotenoids, lycopene and phytofluene, for future biomedical research.

Figure 1.

Carotenoid synthesis pathway in E. coli harboring pAC-LYC, which contains GGPP synthase (crtE), phytoene synthase (crtB) and phytoene desaturase (crtI).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

All bacterial strains and culture media were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and primers for PCR were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralsville, IA). All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswitch, MA), and molecular biology kits were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). All chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and all organic solvents were of HPLC grade and purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburg, PA).

Construction of truncated plasmid pAC-PTE-TR

The plasmid pAC-LYC (Cunningham et al. 26), which contains GGPP synthase (crtE), phytoene synthase (crtB) and phytoene desaturase (crtI) from E. agglomerans, was digested by restriction enzymes Sbf I and Bgl II (NEB), and the digested products were separated on a semi-preparative 0.8% agarose gel. The larger DNA fragment, containing the pACYC-184 backbone, was retrieved with a Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit, blunted by a NEB Quick Blunting Kit and ligated by a NEB Quick Ligation Kit. This truncated pAC-LYC, named pAC-PTE-TR hereafter, was amplified by E. coli strain DH5α and confirmed with electrophoresis and DNA sequencing by an ABI 3730XL capillary sequencer at the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Construction of mutated plasmid pAC-PTE-MT

GeneMorph II Random Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to create the mutant library. The gene crtI was amplified by sense primer 5’-TGACATATGAAAAAAACCGTTGTGATTGGCGCAGGC -3’ and anti-sense primer 5’- ATTCTCGAGTTATCAGGCTGGCGGTGGCTTTCG -3’ per the manufacturer’s instructions for high-error-rate PCR. The PCR products were then purified by a Qiagen PCR Purification Kit and mixed with pAC-LYC. The mixture was digested by restriction enzymes SbfI and BglII, purified by Qiagen PCR Purification Kit, ligated by NEB Quick Ligation Kit, and transformed into E. coli strain DH5α. The transformants were grown on LB agar plates with the antibiotic, chloramphenicol (34 µg/mL), and white colonies were amplified and screened by HPLC for phytoene production. Plasmid pAC-PTE-MT was isolated by a Qiagen Miniprep Kit and the selected mutated-crtI was sequenced.

Bacterial culture in LB broth

Escherichia coli strain BL21Star(DE3) and the transformants were grown and maintained in LB broth supplemented with 34 µg/mL of chloramphenicol at 31°C, 200 rpm. Overnight cultures were used to inoculate 5 mL cultures with a ratio of 1:100, and the cells were grown at 31°C, 200 rpm for 12, 18, 24 and 48 h. Cells were harvested by 3,220 × g centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min, washed with 1X cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), weighed and frozen at −80°C until further analysis.

Bacterial culture in 2XM9 minimal salts media

For carotenoid accumulation and labeling experiments, BL21Star(DE3) and the transformants were grown in 2XM9 media, which contained 5 g/L unlabeled or [U]-13C-glucose, 34 µg/mL of chloramphenicol and doubled amount of salts in 1X M9 media, except for CaCl2 and MgSO4. Overnight cultures from LB were used to inoculate 5 mL cultures with a ratio of 1:100, and the cells were grown at 31°C, 200 rpm for 12, 18, 24 and 48 h. LB broth was removed by centrifugation before cells were inoculated in 2XM9. Cells were harvested by 3,220 × g centrifugation at 4°C for 10 min, washed with 1X cold PBS, weighed and frozen at −80 °C until further analysis.

Analysis of glucose and acetate by HPLC

Glucose and acetate concentrations of culture media were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent Technologies 1200 Series) equipped with a refractive index detector using a Rezex ROA-Organic Acid H+ (8%) column (Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA) kept at 50°C. The mobile phase was 0.005 N of H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The culture media was injected into the system without further purification and the quantification of glucose was calculated based on a standard curve.

Carotenoid extraction

Bacterial cell pellets were thawed on ice, suspended in 50 µL of deionized water and briefly vortexed to achieve homogeneous suspensions. Acetone (500 µL) was then added and followed immediately by a 10-s vortex period and 5-min water-bath sonication. A total of 200 ng of all-trans beta-carotene (DSM, Basel, Switzerland) was added as an internal standard, since the system did not contain any of this cyclic carotenoid. The liquid and solid phases were then separated by 4 °C centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes. The acetone/water phase was transferred to clean centrifuge tubes, evaporated by argon and partitioned by 500 µL of hexanes:methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (1:1, v/v) two times. The extracts were combined and dried down under argon. The samples were stored at −20°C for no more than 24 hours before HPLC analysis, with the entire extraction process performed under yellow light.

Analysis of carotenoids by HPLC

The HPLC system is composed of two pumps (Model SD-200, Rainin Dynamax, Walnut Creek, CA), a YMC Carotenoid C30 column (4.6×250 mm, 3 µm) with a guard column, an 18°C column cooler and a photodiode array detector (Model 2996, Waters, Milford, MA). The mobile phases A (methanol: 15% ammonium acetate aqueous solution= 98:2, v/v) and B (methanol: MTBE: 15% ammonium acetate aqueous solution= 8:90:2, v/v) were used, with the following gradient profile: 0 min, 0% B; 30 min, 100% B; 40 min, 100% B; 45 min, 0% B; 50 min, 0% B. Samples were reconstituted in MTBE for injection and phytoene was measured at 286 nm. Phytoene standards (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany) were prepared in petroleum ether using extinction coefficient A1%, 1 cm 1250 at 286 nm. Lycopene standards (DSM, Basel, Switzerland) were prepared in hexane using extinction coefficient A1%, 1 cm 3450 at 472 nm, and all-trans beta-carotene standards (DSM, Basel, Switzerland) were prepared in n-hexane using extinction coefficient A1%, 1 cm 2592 at 452 nm.

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry was performed by the Mass Spectrometry Center in the School of Chemical Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Unlabeled and labeled samples were purified by HPLC separation and completely dried before sample submission. The lycopene samples were dissolved in acetone and analyzed by Micromass Q-ToF Ultra (Waters, Milford, MA) with electrospray ionization positive mode (ESI+) and high-resolution scanning. The phytoene samples were dissolved in anisole 27 and analyzed by ThermoFinnigan LCQ Deca XP (Thermo Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL) with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization positive mode (APCI+) and low-resolution scanning.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR of crtE and crtB

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). mRNA expression of selected genes was measured via real-time PCR using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Reactions were monitored by an ABI Prism 7900HT. Primer pairs were designed to measure GGDP synthase (crtE) (sense: 5’-GTCAGCCCACTACCCACAAAA-3’; anti-sense: 5’-GCGGCGATCAGACCAAAG-3’), phytoene synthase (crtB) (sense: 5’-GATGAGGGGGTGGTGGAT-3’; anti-sense: 5’-CAATAGCCGCATCGTCAATAATAT-3’), and 16s (rrsB) (sense: 5’-GCATAACGTCGCAAGACCAA-3’; anti-sense: 5’-GCCGTTACCCCACCTACTAGCT-3’). A validation experiment was performed on each set of primers to confirm efficiency and product specificity. A serial dilution was used to create a standard curve for quantification, and 16s was used as a housekeeping gene.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011 was used to perform Student’s t-test. Figures were produced by SigmaPlot 2001 (Systat Software Inc., St. Jose, CA).

Results and Discussion

Lycopene accumulation in BL21Star(DE3) harboring pAC-LYC

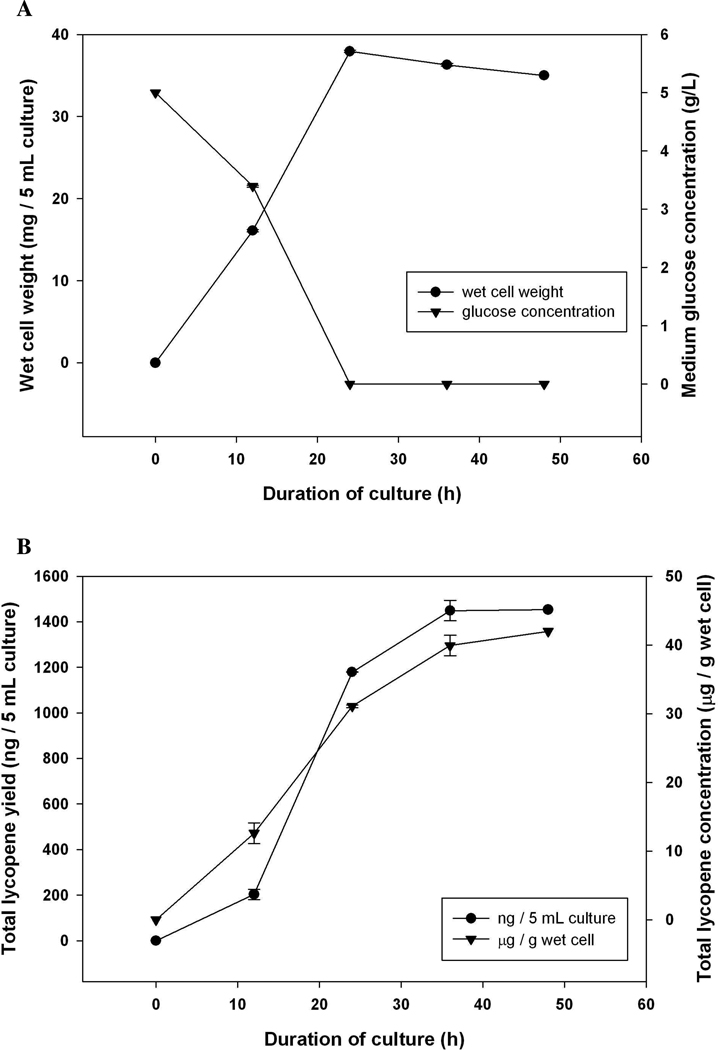

The E. coli strain BL21Star(DE3) harboring the plasmid pAC-LYC, created by Cunningham et al. 26, was used for lycopene production. Prior to the labeling run, E. coli was maintained in LB agar or LB broth. For the labeling run, 2X modified M9 minimal medium was used, which contained doubled nitrogen, and [U]-13C-glucose as the only carbon source to maintain growth characteristics of E. coli that were similar to the culture in LB broth. Initially, 12C-glucose was provided in the 2X M9 minimal medium at the 5 g/L concentration to observe lycopene accumulation; glucose was completely depleted by 24 h (Figure 2A). Over 60% of glucose was used between 12 h and 24 h, which suggested that the cells were in the logarithmic growth phase, which was further confirmed by measuring the OD600 (data not shown) and the wet cell weight (Figure 2A). Wet cell weight reached its maximum at 24 h, and a trace amount of acetate accumulated in the media at 24 h and depleted by 48 h.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of E. coli BL21Star(DE3) harboring pAC-LYC (A) cell growth and the corresponding glucose concentration in 2XM9 media (B) accumulation of total lycopene. Data were presented as mean ± SE with n = 3.

Lycopene concentration was also measured during the 48 h culturing period (Figure 2B). From a 5 mL culture, a total of 1.4 µg lycopene was obtained, 14%, 71% and 15% of which was produced during 0–12 h, 12–24 h and 24–36 h, respectively. Compared with the glucose concentration in the medium, E. coli seemed to continue producing lycopene even though the glucose had been depleted. The metabolic intermediates, acetate or pyruvate, which supported the lycopene production, would potentially be utilized by E. coli during 24–36 h. Interestingly, during the course of culture, the percentage of all-trans lycopene increased over time, and reached over 96% by 24 h (data not shown), which is representative of its level of abundance in tomatoes. Less than 4% of total lycopene was 9-cis and 13-cis, and no other lycopene isomers were detected. Trace amounts of phytoene were observable only from the 12 h samples, indicating that the phytoene desaturase from E. agglomerans was highly efficient in catalyzing the desaturation reaction, which led to the accumulation of the major product, lycopene.

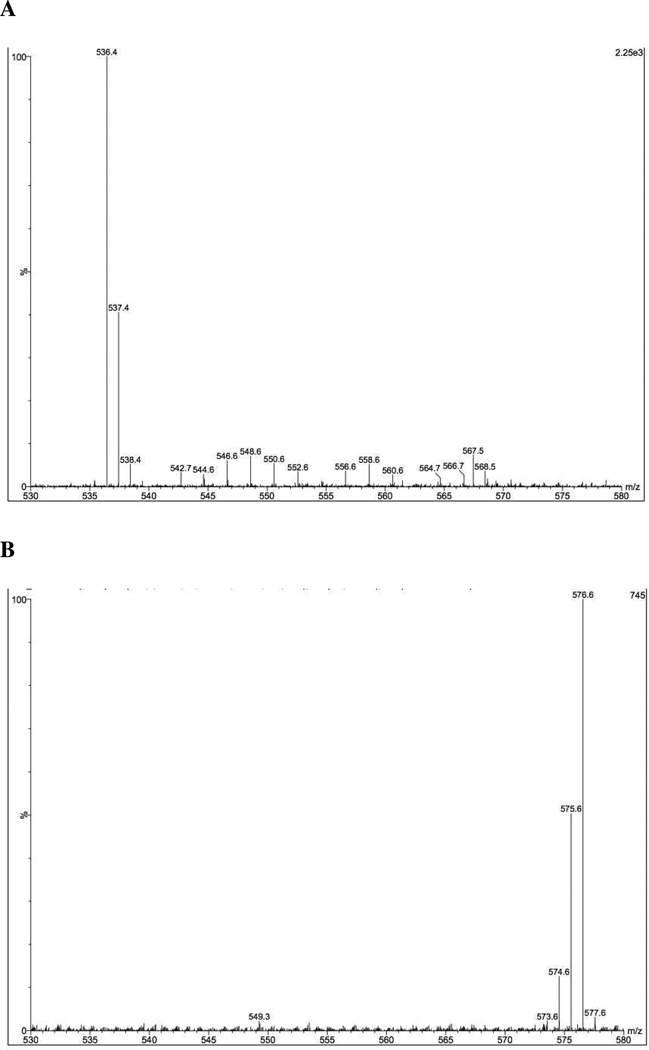

Isotopomer distribution of 13C-labeled lycopene

High-resolution mass spectrometry was used to observe the isotopomer distributions of unlabeled and labeled lycopene (Figure 3). HPLC-purified material was ionized by electrospray ionization and analyzed by a quadrupole mass sector and a time-of-flight mass sector. Under the positive mode of ionization, it was clear that the ion m/z 536.4 [M.] was the majority of the unlabeled lycopene, followed by the ions m/z 537.4, 538.4 and a few other ions ranging between m/z 546.6 and m/z 568.5. Since the natural abundance of 13C is 1.109%, it is expected that a few lycopene molecules would naturally contain some 13C, which resulted in the observation of ions with a higher m/z ratio. Comparing the mass spectra of labeled lycopene with unlabeled lycopene, interestingly, the majority of ions are m/z 576.6 [M+40.], followed by the ions m/z 575.6 [M+39.], and 574.6 [M+38.], which indicates that the biosynthesized lycopene was mostly built from the [U]-13C-glucose and is highly enriched with 13C (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Isotopomer distribution of (A) 12C-all-trans lycopene (12C40H56, MW=536.4) and (B) 13C-labeled all-trans lycopene (13C40H56, MW=576.4). Measured by ESI positive mode in a Q-ToF mass spectrometer.

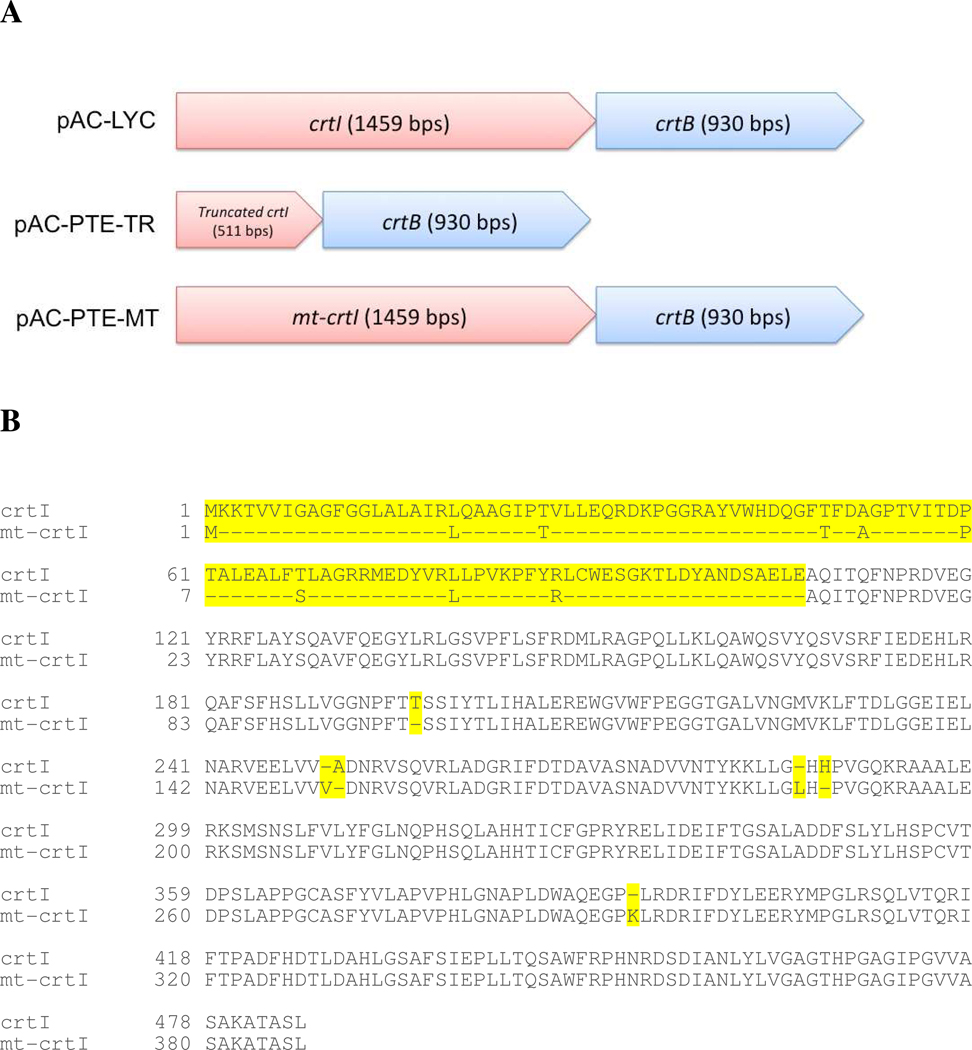

Error-prone PCR rescued phytoene production by maintaining crtB transcription

In the E. agglomerans carotenogenic gene cluster, there are two promoter regions reported by To et al. 28. One of the promoters was located within the gene crtE, and another was located within the gene crtI. Therefore, deletion of crtI could result in the disruption of crtB transcription derived by the promoter within crtI. Therefore, two strategies were applied to create phytoene-accumulating strains: enzymatic digestion and error-prone PCR. Both methodologies were applied to knockout the gene crtI on pAC-LYC and to dysfunction phytoene desaturase, resulting in two plasmids, pAC-PTE-TR (representing “truncated”) and pAC-PTE-MT (representing “mutated”), respectively (Figure 4A). A total of 948 base pairs of crtI open reading frame (ORF) (65% of crtI) were removed from pAC-LYC to create pAC-PTE-TR, whereas the pAC-PTE-MT maintained the same length of ORF as pAC-LYC, but had mutations in crtI. The mutated crtI ORF in the pAC-PTE-MT was sequenced, and the result showed that 101 amino acids were deleted from the protein, and 3 amino acids were inserted to the protein by mutations (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Comparison of plasmid constructs used in this study (A) phytoene desaturase crtI) operons were modified by truncation or mutation (B) alignment of protein sequences of wild-type crtI and mutated crtI.

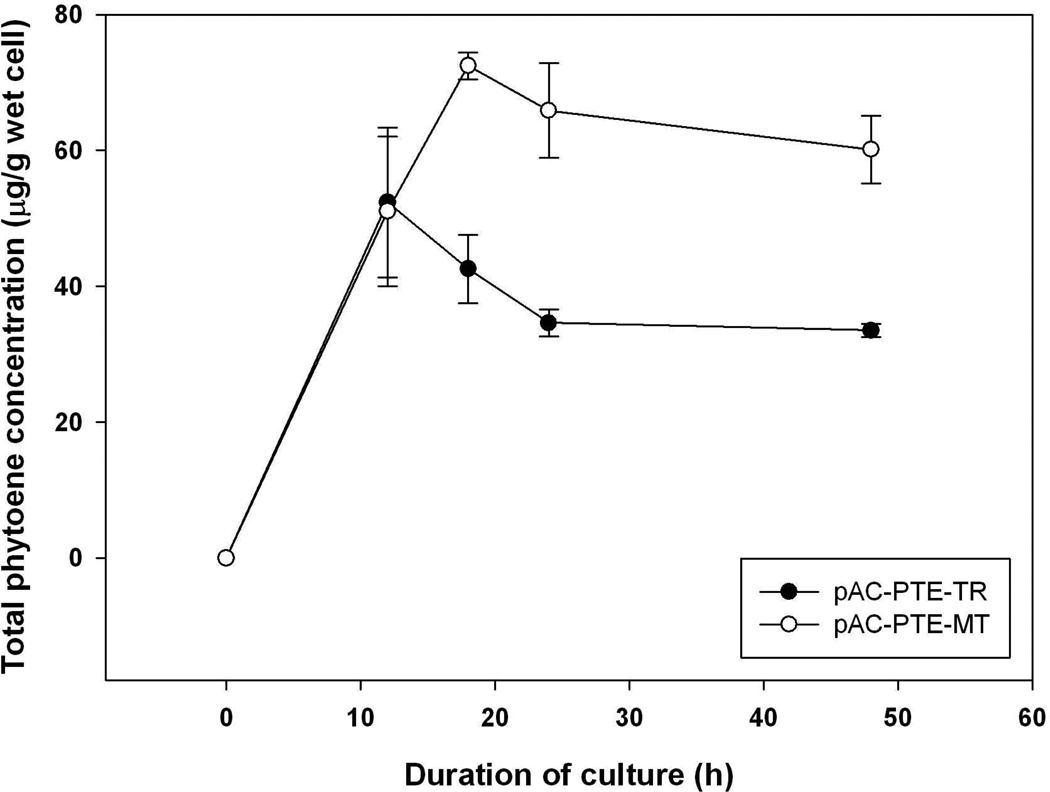

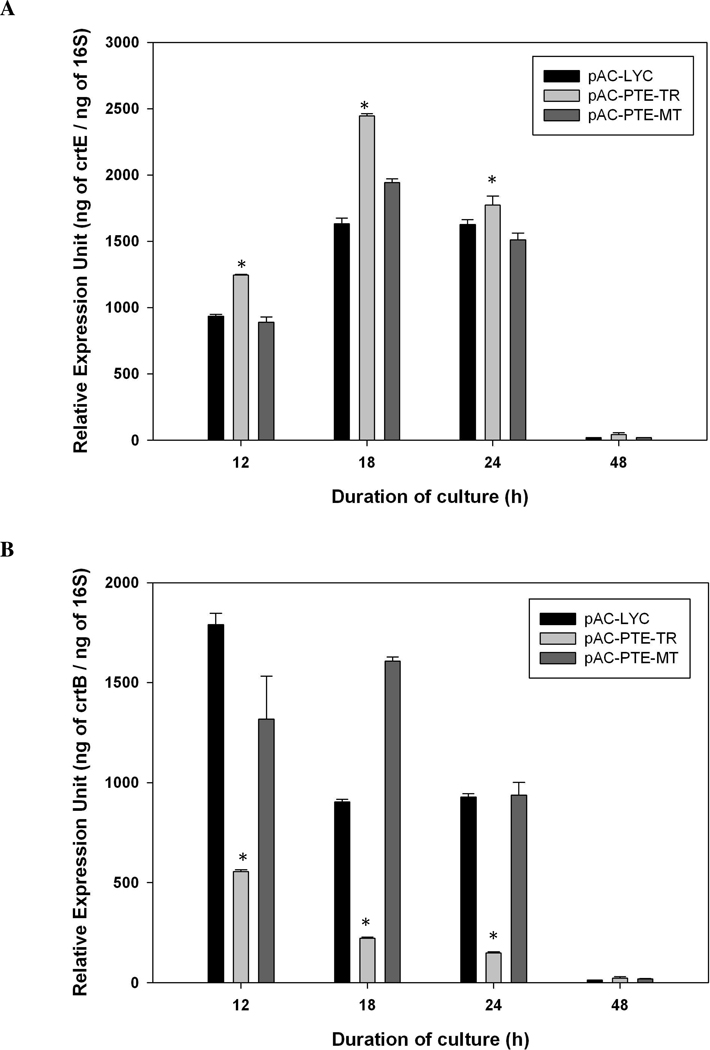

Both plasmids were introduced into BL21Star(DE3) and the phytoene accumulation patterns were evaluated. Both plasmids resulted in phytoene accumulation, and both strains, which were cultured in LB broth, accumulated higher concentrations of carotenoids than in minimal medium. Interestingly, E. coli harboring pAC-PTE-MT accumulated more phytoene than the one harboring pAC-PTE-TR (Figure 5). The transcription of either GGDP synthase (crtE) or phytoene synthase (crtB) was potentially affected by the enzyme digestion of crtI, and therefore the real-time PCR was used to evaluate total RNA level of crtE or crtB among tested strains. The RNA expression of crtE was slightly higher in pAC-PTE-TR compared with pAC-LYC or pAC-PTE-MT (Figure 6A), but the expression of crtB was significantly decreased (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Phytoene accumulation in E. coli BL21Star(DE3) harboring pAC-PTE-TR and pAC-PTE-MT, cultured in LB broth. Data were presented as mean ± SD with n = 2.

Figure 6.

RNA expression patterns of E. coli harboring pAC-LYC, pAC-PTE-TR, and pAC-PTE-MT in LB broth (A) GGPP synthase (crtE) (B) phytoene synthase (crtB). Data were presented as mean ± SE with n = 3. *p<0.05

In this study, the deletion of crtI ORF reduced the mRNA transcription of crtB and further resulted in decreased phytoene accumulation, suggesting that the promoter within the crtI ORF is involved in the transcription of crtB. Using error-prone PCR methodology, a mutated crtI that potentially maintained the promoter region within crtI was generated; this promoter maintained the transcription of crtB and resulted in a higher phytoene accumulation compared with truncated crtI. In addition, there may be a polar effect between crtI and crtB in which the mRNA is more stable if the two genes are transcribed together. Therefore, error-prone PCR rescued phytoene production by maintaining crtB transcription, and the E. coli harboring pAC-PTE-MT was selected as the model for further 13C-labeling.

In addition, hundreds of mutant colonies harboring mutated crtI as well as functional crtB and crtE were screened by UV lamp to locate a phytofluene-accumulating colony, but none of the colonies was identified to accumulate phytofluene. All screened mutants accumulated phytoene. Many studies have characterized diverse products by combining crtI-type phytoene desaturases from different species in E. coli 29. Although the active site of phytoene desaturase from E. agglomerans has not been thoroughly studied, based on our error-prone PCR results, we suspect that once the active site is disabled, the enzyme entirely loses its function and is unable to catalyze any desaturation reaction. Error-prone PCR could not generate a mutated phytoene desaturase that only catalyzes 1, 2 or 3 steps of the desaturation cascade.

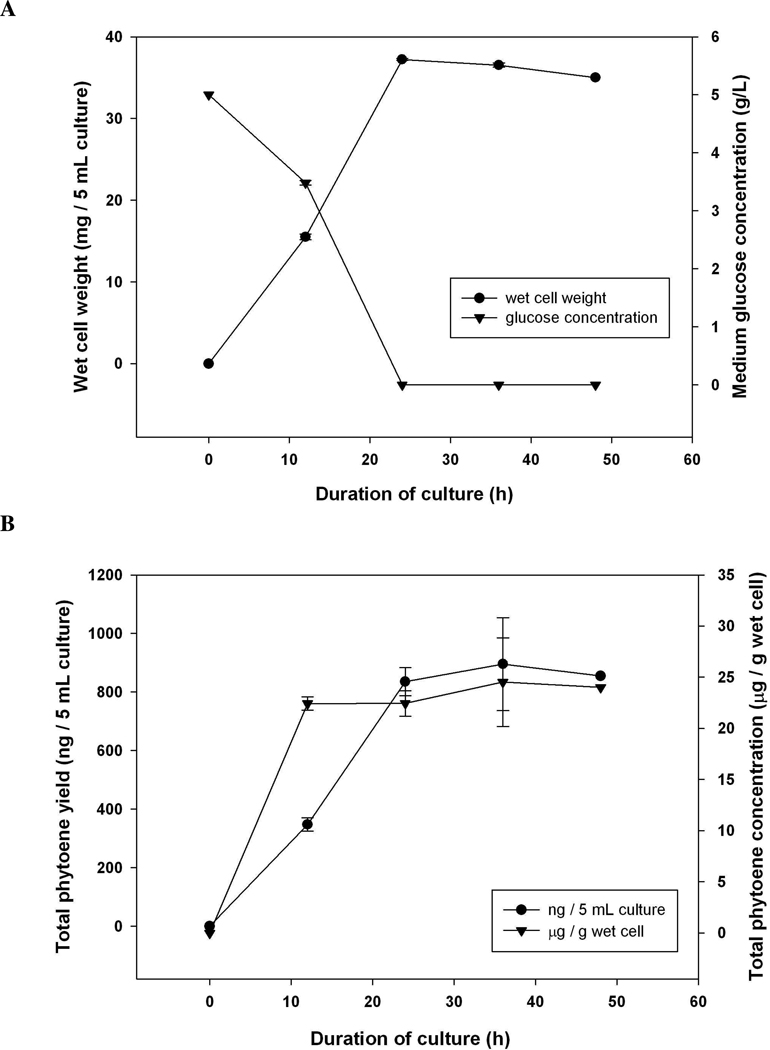

Phytoene accumulation in BL21Star(DE3)

The E. coli strain BL21Star(DE3) harboring pAC-PTE-MT was grown in 2XM9 minimal medium containing 5 g/L 12C-glucose, and its growth characteristics were similar to the strain harboring pAC-LYC (Figure 7A). Over 60% of glucose was used between 12 h and 24 h, and the wet cell weight reached its maximum at 24 h. The total phytoene accumulation per 5-mL-culture reached 836 ng by 24 h and further reached to 896 ng by 36 h (Figure 7B). Accumulated phytoene were mainly 15-cis and all-trans phytoene, and no other phytoene isomers were detected. Interestingly, the phytoene accumulation per gram of wet cells reached its steady state at 12 h and maintained at a similar level, indicating that phytoene accumulation was taking place while E. coli was growing. After E. coli reached its maximum cell mass, the synthesis of phytoene stopped, which is different from the pattern observed with lycopene accumulation. A trace amount of acetate was also accumulated in the media at 24 h and depleted by 48 h.

Figure 7.

Characteristics of E. coli BL21Star(DE3) harboring pAC-PTE-MT (A) cell growth and corresponding glucose concentration of 2XM9 media (B) accumulation of total phytoene. Data were presented as mean ± SE with n = 3.

Phytoene synthase catalyzes a condensation reaction and yields phytoene, whereas phytoene desaturase catalyzes desaturation reactions and yields lycopene. In general, a desaturation reaction is not spontaneous but requires an energizing component. Unlike fatty acid desaturation, which yields an isolated double bond by NADH-dependent hydroxylation and water abstraction, desaturation of phytoene and other carotenes is thermodynamically favored due to the resulting extension of the conjugated double bond system, which is an exergonic reaction 29. Therefore, the desaturation reaction might be continued even though the glucose was depleted in the media, whereas the condensation reaction was stopped.

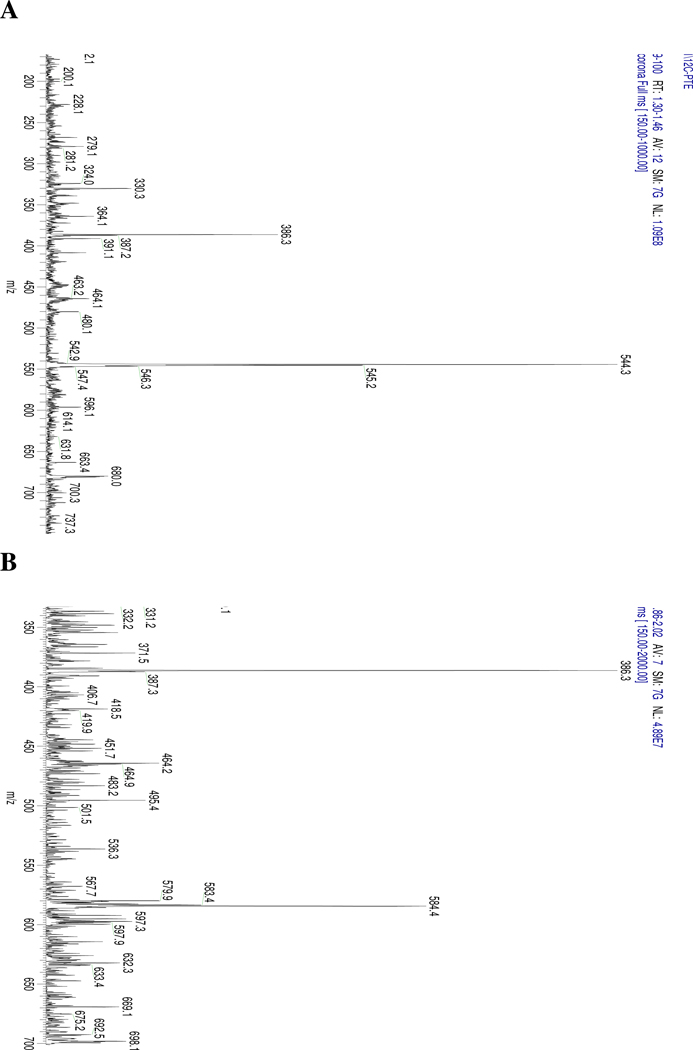

Isotopomer distribution of 13C-labeled phytoene

Mass spectrometry showed that the ion m/z 544.3 was the major ion for the unlabeled phytoene, followed by m/z 545.2 and m/z 546.3 (Figure 8), which was similar to what we observed with unlabeled lycopene sample. Comparing mass spectra of labeled phytoene with unlabeled phytoene, we observed the majority of ions shifted to m/z 584.4 [M+40.], followed by the ions m/z 583.4 [M+39.], which indicates that the biosynthesized phytoene is enriched with 13C. Mass spectrometry of phytoene was performed using APCI under positive mode, which led to a detectable signal, while ESI did not. A similar finding was reported by Rivera et al. 27.

Figure 8.

Isotopomer distribution of (A) 12C- phytoene (12C40H64, MW=544.3) (B) 13C-labeled phytoene (13C40H64, MW=584.4). Measured by ThermoFinnigan LCQ Deca XP with APCI+ interface.

Advantages and disadvantages of using E. coli to produce isotopically labeled carotenoids

Bioengineered E. coli have the potential to generate a wide variety of carotenoids by combining different carotenogenic genes from different bacteria. For example, combining phytoene synthase from E. agglomerans and phytoene desaturase from a Rhodobacter species that catalyzes only 3 steps of desaturation would generate molecules like beta-zeacarotene and hydroxyneurosporene, instead of lycopene 30. Furthermore, molecular breeding or in vitro evolution techniques have also been applied to create novel carotenoids in E. coli. Schmidt-Dannert et al. expressed a shuffled phytoene desaturase in E. coli and created a fully conjugated carotenoid, 3, 4, 3’, 4’-tetradehydrolycopene 19. The C30 pathway was also tested and a novel cyclic carotenoid, C30-diapotorulene, was produced 31. Therefore, by utilizing an E. coli system, labeled carotenoids with novel or rare structures may be easily biosynthesized. In addition, since [U]-13C-glucose is the only carbon source in the minimal medium, 12C carry-over could be low, resulting in highly-uniformly labeled products.

E. coli is relatively easy to maintain and culture for a biosafety level-2 laboratory and the operation can be managed by an entry-level scientist. In addition, laboratory-scale production can be performed on site, which can provide freshly biosynthesized carotenoids to avoid oxidized or degraded contaminants. In contrast, chemical synthesis of carotenoids is lengthy and it requires experienced organic chemists and a sophisticated organic chemistry laboratory. For mass spectrometry internal standard purposes, E. coli produces customized labeled carotenoids in 36 h, and the purification process is relatively simple compared with the extractions from other biotechnological production systems, such as tomato cell culture 32 or microalgae 33.

However, like every biotechnological production system, by-products can be produced and extracted during the process, requiring further purification with liquid chromatography. Also, unlike chemical synthesis, it is challenging to label specific atoms in the biosynthesized molecules, since special labeled precursors could be costly. For this model system, one 5 mL culture produced 1.4 µg of 13C-labeled lycopene, which costs an estimated $1.25. Although this model system may not be cost-effective, research has been devoted to improve carotenoid production. For examples, the supply of carotenoid synthesis precursor IPP had been improved by Kim et al. 34, which doubled the lycopene production. Introducing the mevalonate pathway resulted in a 10-fold increase in lycopene production 35. Gene knockout strategies have also been applied to improve lycopene production, resulting in a strain that can accumulate 16 mg of lycopene /g dry cell mass 23–25. These metabolic-engineered strains could potentially make the E. coli system cost-effective for labeled carotenoid production.

Summary

This research demonstrated that bioengineered E. coli could utilize [U]-13C-glucose to produce highly 13C-enriched tomato carotenoids, lycopene and phytoene, and that error-prone PCR maintained phytoene production by maintaining the transcription of phytoene synthase. This production system could be further optimized and provide sufficient labeled carotenoids for future absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion studies of carotenoids.

Acknowledgement

This research is supported in part by NIH R21-AT005166-02

Literature Cited

- 1.Canene-Adams K, Campbell JK, Zaripheh S, Jeffery EH, Erdman JW., Jr The Tomato as a Functional Food. J Nutr. 2005;135:1226–1230. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.5.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breemen RB van, Pajkovic N. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by lycopene. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker RS, Swanson JE, Marmor B, Goodman KJ, Spielman AB, Brenna JT, Viereck SM, Canfield WK. Study of beta-carotene metabolism in humans using 13C-beta-carotene and high precision isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Ann NY Aacd Sci. 1993;691:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao L, Liang Y, Trahanovsky WS, Serfass RE, White WS. Use of a 13C tracer to quantify the plasma appearance of a physiological dose of lutein in humans. Lipids. 2000;35:339–348. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novotny JA, Dueker SR, Zech LA, Clifford AJ. Compartmental analysis of the dynamics of beta-carotene metabolism in an adult volunteer. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:1825–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang G, Qin J, Dolnikowski GG, Russell RM. Vitamin A equivalence of beta-carotene in a woman as determined by a stable isotope reference method. Eur J Nutr. 2000;39:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s003940050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdegem PJ, Bovee-Geurts PH, Grip WJ de, Lugtenburg J, Groot HJ de. Retinylidene ligand structure in bovine rhodopsin, metarhodopsin-I, and 10-methylrhodopsin from internuclear distance measurements using 13C-labeling and 1-D rotational resonance MAS NMR. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11316–11324. doi: 10.1021/bi983014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lienau A, Glaser T, Tang G, Dolnikowski GG, Grusak MA, Albert K. Bioavailability of lutein in humans from intrinsically labeled vegetables determined by LC-APCI-MS. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borowitzka M. Commercial production of microalgae: ponds, tanks, tubes and fermenters. J Biotechnol. 1999;70:313–321. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carvalho AP, Meireles LA, Malcata FX. Microalgal reactors: a review of enclosed system designs and performances. Biotechnol Progr. 2006;22:1490–1506. doi: 10.1021/bp060065r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campo JA, García-González M, Guerrero MG. Outdoor cultivation of microalgae for carotenoid production: current state and perspectives. Appl Microbiol and Biot. 2007;74:1163–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell JK, Rogers RB, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Biosynthesis of 14C-phytoene from tomato cell suspension cultures (Lycopersicon esculentum) for utilization in prostate cancer cell culture studies. J Agr Food Chem. 2006;54:747–755. doi: 10.1021/jf0581269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelmann NJ, Rogers RB, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Herbicide treatments alter carotenoid profiles for 14C tracer production from tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. VFNT cherry) cell cultures. J Agr Food Chem. 2009;57:4614–4619. doi: 10.1021/jf803905d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelmann NJ, Campbell JK, Rogers RB, Rupassara SI, Garlick PJ, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Screening and selection of high carotenoid producing in vitro tomato cell culture lines for [13C]-carotenoid production. J Agr Food Chem. 2010;58:9979–9987. doi: 10.1021/jf101942x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry KL, Simonitch TA, Harrison-Lavoie KJ, Liu ST. Cloning and regulation of Erwinia herbicola pigment genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:607–612. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.607-612.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong GA, Alberti M, Hearst JE. Conserved enzymes mediate the early reactions of carotenoid biosynthesis in nonphotosynthetic and photosynthetic prokaryotes. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9975–9979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harada H, Misawa N. Novel approaches and achievements in biosynthesis of functional isoprenoids in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol and Biot. 2009;84:1021–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandmann G. Combinatorial biosynthesis of carotenoids in a heterologous host: a powerful approach for the biosynthesis of novel structures. Chembiochem. 2002;3:629–635. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<629::AID-CBIC629>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt-Dannert C, Umeno D, Arnold FH. Molecular breeding of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:750–753. doi: 10.1038/77319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umeno D, Tobias AV, Arnold FH. Diversifying carotenoid biosynthetic pathways by directed evolution. Microbiol Mol Biol R. 2005;69:51–78. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.51-78.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon S-H, Lee S-H, Das A, Ryu H-K, Jang H-J, Kim J-Y, Oh D-K, Keasling JD, Kim S-W. Combinatorial expression of bacterial whole mevalonate pathway for the production of beta-carotene in E. coli. J Biotechnol. 2009;140:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albrecht M, Misawa N, Sandmann G. Metabolic engineering of the terpenoid biosynthetic pathway of Escherichia coli for production of the carotenoids β-carotene and zeaxanthin. Biotechnol Lett. 1999;21:791–795. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alper H, Jin Y-S, Moxley JF, Stephanopoulos G. Identifying gene targets for the metabolic engineering of lycopene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2005;7:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin Y-S, Stephanopoulos G. Multi-dimensional gene target search for improving lycopene biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng. 2007;9:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alper H, Stephanopoulos G. Uncovering the gene knockout landscape for improved lycopene production in E. coli. Appl Microbiol and Biot. 2008;78:801–810. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham FX, Sun Z, Chamovitz D, Hirschberg J, Gantt E. Molecular structure and enzymatic function of lycopene cyclase from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp strain PCC7942. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1107–1121. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.8.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivera S, Vilaró F, Canela R. Determination of carotenoids by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry: effect of several dopants. Anal and Bioanal Chem. 2011;400:1339–1346. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-4825-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.To KY, Lai EM, Lee LY, Lin TP, Hung CH, Chen CL, Chang YY, Liu ST. Analysis of the gene cluster encoding carotenoid biosynthesis in Erwinia herbicola Eho13. Microbiology. 1994;140:331–339. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandmann G. Evolution of carotene desaturation: the complication of a simple pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandmann G, Albrecht M, Schnurr G, Knörzer O, Böger P. The biotechnological potential and design of novel carotenoids by gene combination in Escherichia coli. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:233–237. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(99)01307-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee PC, Momen AZR, Mijts BN, Schmidt-Dannert C. Biosynthesis of structurally novel carotenoids in Escherichia coli. Chem Biol. 2003;10:453–462. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu C-H, Engelmann NJ, Lila MA, Erdman JW., Jr Optimization of lycopene extraction from tomato cell suspension culture by response surface methodology. J Agr Food Chem. 2008;56:7710–7714. doi: 10.1021/jf801029k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson PDG, Hilton MG, Waspe CR, Steer DC, Wilson DR. Production of C-13-labelled beta-carotene from Dunaliella salina. Biotechnol Lett. 1997;19:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SW, Keasling JD. Metabolic engineering of the nonmevalonate isopentenyl diphosphate synthesis pathway in Escherichia coli enhances lycopene production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2001;72:408–415. doi: 10.1002/1097-0290(20000220)72:4<408::aid-bit1003>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodríguez-Villalón A, Pérez-Gil J, Rodríguez-Concepción M. Carotenoid accumulation in bacteria with enhanced supply of isoprenoid precursors by upregulation of exogenous or endogenous pathways. J Biotechnol. 2008;135:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]