Abstract

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) promotes osteoblast survival through a mechanism that depends on cAMP-mediated signaling downstream of the G protein-coupled receptor PTHR1. We present evidence herein that PTH-induced survival signaling is impaired in cells lacking connexin43 (Cx43). Thus, expression of functional Cx43 dominant negative proteins or Cx43 knock-down abolished the expression of cAMP-target genes and anti-apoptosis induced by PTH in osteoblastic cells. In contrast, cells lacking Cx43 were still responsive to the stable cAMP analog dibutyril-cAMP. PTH survival signaling was rescued by transfecting wild type Cx43 or a truncated dominant negative mutant of βarrestin, a PTHR1-interacting molecule that limits cAMP signaling. On the other hand, Cx43 mutants lacking the cytoplasmic domain (Cx43Δ245) or unable to be phosphorylated at serine 368 (Cx43S368A), a residue crucial for Cx43 trafficking and function, failed to restore the anti-apoptotic effect of PTH in Cx43-deficient cells. In addition, overexpression of wild type βarrestin abrogated PTH survival signaling in Cx43-expressing cells. Moreover, βarrestin physically associated in vivo to wild type Cx43 and to a lesser extent to Cx43S368A; and this association and the phosphorylation of Cx43 in serine 368 were reduced by PTH. Furthermore, induction of Cx43S368 phosphorylation or overexpression of wild type Cx43, but not Cx43Δ245 or Cx43S368A, reduced the interaction between βarrestin and the PTHR1. These studies demonstrate that βarrestin is a novel Cx43-interacting protein and suggest that, by sequestering βarrestin, Cx43 facilitates cAMP signaling, thereby exerting a permissive role on osteoblast survival induced by PTH.

Keywords: Cx43, βarrestin, PTH, osteoblast survival

Introduction

Repeated cycles of systemic elevation of parathyroid hormone (PTH)1 by daily injections leads to a potent bone anabolic effect (Hodsman et al., 2005;Jilka, 2007). Increased bone mass results from a marked elevation in bone formation rate and in the number of osteoblasts covering cancellous, endocortical, as well as periosteal bone surfaces. Moreover, constitutive activation of the PTH receptor 1 (PTHR1) in osteoblastic cells is sufficient to cause bone anabolism (Calvi et al., 2001;O’Brien et al., 2008). One potential mechanism for the anabolic effect of PTH is prolongation of the lifespan of mature osteoblasts. Thus, intermittent PTH decreases the prevalence of osteoblast apoptosis in murine cancellous bone (Jilka et al., 1999;Bellido et al., 2003); and conversely, mice with conditional deletion in osteoblastic cells of PTH-related protein (PTHrP), the other ligand of the PTHR1, exhibit increased osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis (Miao et al., 2005;Martin, 2005). In vitro studies demonstrated that PTH and PTHrP directly activate pro-survival signaling in murine and human osteoblastic cells, by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms downstream of cyclic AMP (cAMP)/protein kinase A (PKA) activation (Jilka et al., 1999;Bellido et al., 2003).

Recent evidence showed that PTH fails to induce full bone anabolism in mice lacking connexin43 (Cx43) (Chung et al., 2006), the most abundant member of the connexin family of proteins expressed in bone cells (Civitelli, 2008). Thus, the increase in bone mineral content and mineral apposition rate, a measure of the work of individual osteoblasts, induced by daily PTH injections are diminished in mice lacking Cx43 in osteoblastic cells. Earlier studies demonstrated that cultured osteoblastic cells in which Cx43 expression was reduced with anti-sense oligonucleotides displayed blunted cAMP production in response to PTH (Vander Molen et al., 1996). This evidence notwithstanding, the mechanistic basis for the requirement of Cx43 for the effective response of osteoblastic cells to PTH in vivo and in vitro remains unknown.

The effects mediated by connexins have been traditionally ascribed to gap junction channels consistent of two hemichannels, each of them formed by six connexin molecules and contributed by neighboring cells. However, more recent studies demonstrate that hemichannels expressed in unopposed cell membranes function independently of cell-to-cell communication and mediate the exchange of low molecular size molecules between cells and the extracellular milieu (Goodenough and Paul, 2003). In addition, Cx43 regulates intracellular signaling acting as a scaffold that fosters protein-protein interactions through domains located in its cytoplasmic C-terminus tail (Giepmans, 2004;Goodenough and Paul, 2003). We have previously demonstrated a novel function of the C-terminus of Cx43 in mediating the transduction of cell survival signals induced by the anti-osteoporosis drugs bisphosphonates in osteoblasts and osteocytes (Plotkin et al., 2002). Thus, bisphosphonates open Cx43 hemichannels and induce the interaction of Cx43 with the kinase Src, followed by activation of the ERK pathway and inhibition of osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis (Plotkin et al., 2002;Plotkin et al., 2005). This evidence raises the possibility that a similar scaffolding function of Cx43 could be required for the survival effect of PTH in osteoblastic cells.

Herein, we demonstrate that osteoblastic cells lacking Cx43 are refractory to the anti-apoptotic actions of PTH due to a deficient cAMP-mediated response. We show that the requirement of Cx43 for PTH action is due to the ability of Cx43 to interact with, thereby sequestering, βarrestin. βarrestin is an intracellular protein that is recruited to PTHR1 upon ligand binding, reduces the affinity of PTHR1 to Gsα, thus suppressing cAMP responses (Premont and Gainetdinov, 2007). In addition, βarrestin induces clathrin-dependent internalization of PTHR1, leading to its degradation or recycling (Ferrari et al., 1999). We found that Cx43/βarrestin interaction is mediated through the cytoplasmic C-terminus domain of Cx43 and requires phosphorylation of serine 368, thus identifying a new site responsible for Cx43-protein interactions. These studies provide the mechanistic basis for the requirement of Cx43 for PTH receptor signaling and define a previously unrecognized scaffolding function of Cx43 that modulates signal transduction in osteoblasts.

Materials & Methods

Materials

Etoposide, 18-α-glycyrrhetinic acid (AGA), glycyrrhizic acid (GA), and the cAMP analog dibutyril-cAMP (DBA) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO); bovine PTH (1–34) was purchased from Bachem (Torrance, CA). Dithiobis-(succinimidyl-propionate) (DSP) was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL).

Cell culture and generation of Cx43-deficient OB-6 cells

Wild type murine bone marrow-derived OB-6 osteoblastic cells were generated and cultured as previously described (Lecka-Czernik et al., 1999). Cells were maintained in α-MEM medium containing L-glutamine and 1 % v/v penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), 10 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), and 25 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO). The expression of Cx43 in OB-6 cells was silenced using MISSION short hairpin (sh)RNA Lentiviral Particles (Sigma), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The efficiency of deletion was determined by quantifying Cx43 protein and mRNA levels by Western blotting and by qPCR, respectively.

Real time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was obtained using Ultraspec RNA isolation reagent (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX). Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster city, CA, USA). Assay on Demand or Assay by Design primer probe pair sets were used and the PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μl using the Gene Expression Assay Mix and the TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster city, CA, USA), containing 80 ng of each cDNA template in triplicates, using an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR system. The fold change in expression was calculated using the Δ ΔCt comparative threshold cycle method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

DNA constructs and transient transfection

The plasmids encoding nuclear targeted green fluorescent protein (nGFP) and red fluorescent protein (nRFP) were previously described (Plotkin et al., 1999;Kousteni et al., 2001). Wild type rat Cx43 and chick Cx45 were provided by R. Civitelli (Washington University, Saint Louis, MO). The mutant Cx43Δ245 and Cx43 C-terminus tail were provided by B. Nicholson (The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX). Cx43 mutant lacking seven residues from the internal loop at positions 130–136 (Cx43Δ130) was provided V. A. Krutovskikh (International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France). Cx43cys-less was a gift from Dr. G. M. Kidder (The University of Western Ontario, Ontario, Canada). Cx43 serine 368 to alanine (Cx43S368A) mutant was provided by P. Lampe (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). Cx43-GFP was a gift from D.W. Laird (University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada) (Roscoe et al., 2005). The construct for βarrestin1-tdRFP was provided by L.M. Traub (University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA) (Keyel et al., 2008). Wild type βarrestin and βarrestin319–418 constructs were provided by K. DeFea (DeFea et al., 2000b). These constructs have been shown to be normally expressed at the protein and mRNA levels. Moreover, changes in the expression of osteoblast markers such as osteocalcin, cell-to-cell communication and hemichannel opening have been shown to occur upon overexpression of wild type Cx45 and Cx43 and Cx43 mutants in several cell types, including osteoblastic cells [wt Cx43 (Lecanda et al., 1998); Cx43Δ245 (Zhou et al., 1999); Cys-less Cx43 (Tong et al., 2007); Cx43Ser368 (Lampe et al., 2000); Cx43Δ130, (Krutovskikh et al., 1998)]. Specifically for apoptosis, we have shown that Cx45 and Cx43 and its mutants alter the response to anti-apoptotic agents using MLO-Y4 osteocytic and HeLa cells (Plotkin et al., 2002;Plotkin et al., 2005).

Cells were transiently transfected with a total amount of DNA of 0.1 μg/cm2 using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen) as previously described (Plotkin et al., 2002). The efficiency of transfection was ~60%.

Quantification of apoptotic cells

Apoptosis was induced in semi-confluent cultures (less than 75% confluence). Cells were treated with vehicle (acetic acid 0.1%) or 50 nM PTH for 1 h, followed by treatment with 50 μM etoposide for 6 h, as previously reported (Bellido et al., 2003). Apoptosis was assessed by Trypan blue uptake or by enumerating OB-6 cells expressing nGFP or nRFP exhibiting chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation under a fluorescence microscope. At least 250 cells from fields selected by systematic random sampling for each experimental condition were examined in all apoptosis assays.

Western Blot analysis and immunoprecipitation

Immunoblottings were performed using a rabbit anti-phosphorylated Cx43S368 antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA) or rabbit anti-Cx43 antibody that recognizes both the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated protein (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The intensity of the bands was quantified using the Fotodyne system (Hartland, WI). For immunoprecipitation experiments, Cx43-silenced cells were plated at a density of 4.4×104/cm2 and twenty-four h later cells were transfected with rat wild type Cx43 using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Forty-eight h later, cells were cross-linked using 0.1 mM DSP for 30 min at room temperature. Each plate was lysed with 0.1 ml of RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase inhibitors (sodium fluoride, sodium orthovanadate) and protease inhibitors (leupeptin, aprotinin). Immunoprecipitation was performed using 600 μg of extracts and 2 μg of anti-Cx43 (Sigma), overnight at 4°C. Complexes were collected with 50 μl of 25 % slurry of protein-G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Confocal microscopy

Cells were grown on microscope coverslips and transfected with Cx43-GFP and βarrestin1-tdRFP. Forty eight h after transfection, coverslips were mounted onto slides in Mowiol™ 4–88 supplemented with DABCO (1:5) as anti-fade reagent. Cells were visualized using a Leica TCS SP laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a 488 nm argon laser, a 543 nm HeNe laser and a 63× oil fluorescence objective.

PTHR1/βarrestin binding assay

The ability of Cx43 to interfere with the binding between PTHR1 and βarrestin2 was evaluated using a commercially available kit, PathHunter (DiscoverX, Fremont, CA). The provided CHO cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. For the experiments with the gap junction inhibitors, 48 h after plating, cells were treated with either 100 μM AGA or 100 μM GA for 30 min, followed by 50 nM PTH (1–34) for 90 min. Substrate addition and plate reading were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. For Cx43 overexpression, cells were transfected with 0.1 μg per well of the appropriate construct, using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). After 48 h, the assay was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed student t-test or by one-way analysis of variance, and the Student-Newman-Keuls method was used to estimate the level of significance of differences between means.

RESULTS

Cx43 is required for PTH-induced osteoblast survival and transcription of cAMP-target genes

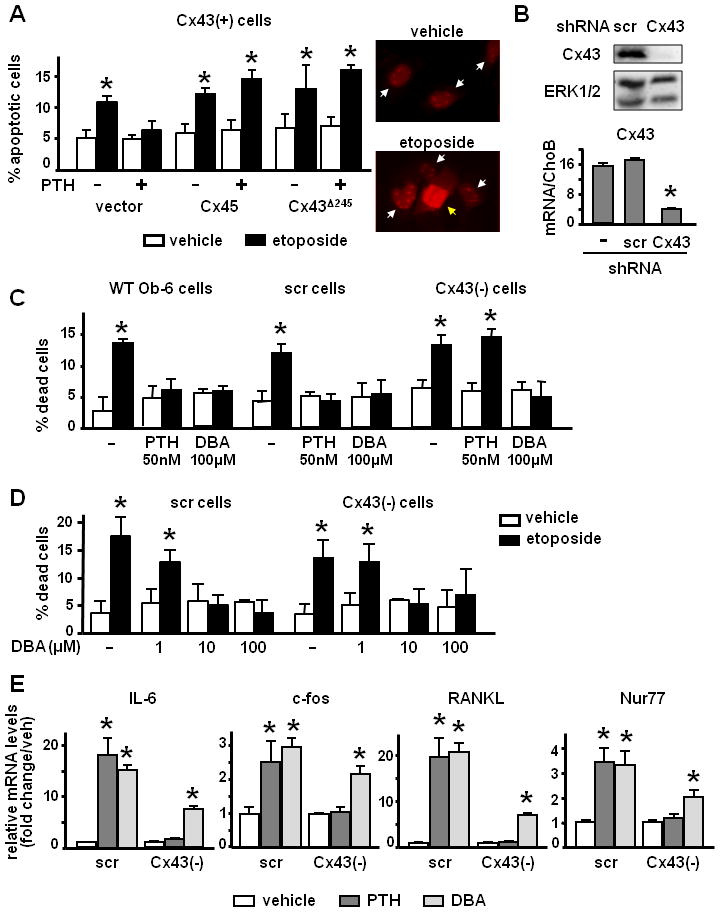

We investigated whether interfering with Cx43 function altered the response of osteoblasts to PTH. Consistent with previous findings (Bellido et al., 2003;Jilka et al., 1999), addition of 50 nM PTH 1 h before treatment with the pro-apoptotic agent etoposide prevented the increase in apoptosis in OB-6 osteoblastic cells. However, PTH did not prevent apoptosis in cells expressing Cx45, another member of the connexin family expressed in osteoblastic cells shown to interfere with Cx43-mediated responses (Plotkin et al., 2002;Lecanda et al., 1998;Steinberg et al., 1994). Cx45 is highly homologous to Cx43, but harbors a different C-terminus (Beyer et al., 1990), suggesting that the C-tail of Cx43 mediates the responsiveness to PTH. Indeed, PTH failed to inhibit apoptosis in cells expressing a truncated form of Cx43 lacking the cytoplasmic C-terminus domain (Cx43Δ245) that also acts as a dominant negative (Plotkin et al., 2002;Zhou et al., 1999) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Cx43 expression is required for PTH-mediated survival signals and transcription of cAMP-target genes in osteoblasts.

(A) OB-6 cells were transfected with vector or the indicated constructs and treated with 50 nM PTH or the corresponding vehicle for 1 h, followed by 50 μM etoposide for 6 h. Apoptosis was assessed by evaluating nuclear morphology of transfected (fluorescent) cells as detailed under Experimental Procedures. Representative images of vehicle- and etoposide-treated cultures show alive (white arrows) and apoptotic (yellow arrow) nuclei. (B) Cx43 protein and mRNA expression were assessed by Western blotting and qPCR, respectively, in wild type OB-6 cells or cells infected with scramble shRNA or Cx43-specific shRNA. Values were normalized against the housekeeping protein ERK1/2 or to CHOB mRNA levels. N=3, * p < 0.05 versus scr cells. (C) OB-6 that were not infected (−) or stably infected with scramble shRNA (scr cells) or Cx43-specific shRNA [(Cx43(−) cells] were treated with 50 nM PTH, 100 μM DBA or the corresponding vehicle for 1 h, followed by 50 μM etoposide for 6 h. Apoptosis was assessed by Trypan blue uptake. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cultures. (D) Scr and Cx43 (−) cells were treated with vehicle (−) or the indicated concentrations of DBA for 1 h, followed by 50 μM etoposide for 6 h. Apoptosis was assessed by Trypan blue uptake. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cultures. (E) Messenger RNA expression levels of the indicated genes in scr and Cx43-deficient cells treated with 100 nM PTH, 150 μM DBA or the corresponding vehicle for 4 h, followed by RNA extraction and qPCR as described in Experimental Procedures. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cultures.

We next studied the requirement of Cx43 for PTH anti-apoptotic effect using a stable cell line previously generated (Plotkin et al., 2008) in which the expression of the protein was silenced using short hairpin (sh) RNA. As shown previously (Plotkin et al., 2008), Cx43 protein and mRNA were decreased compared to scramble shRNA-infected cells as measured by Western blotting and qPCR, respectively, whereas Cx43 mRNA levels were similar in wild type and scramble-infected cells (Figure 1B). PTH prevented etoposide-induced apoptosis in non-infected cells or cells infected with scramble shRNA; however it failed to do so in Cx43 silenced cells, named Cx43(−) (Figure 1C). Similar lack of responsiveness to PTH was found in OB-6 cells silenced with a different Cx43 shRNA (not shown). In contrast, cells silenced for Cx43 were protected from etoposide-induced apoptosis by 100 μM concentration of DBA, the stable analog of cAMP which we have previously shown to mimic PTH induced anti-apoptosis in osteoblasts (Jilka et al., 1999;Bellido et al., 2003) (Figure 1C). Moreover, whereas 1 μM DBA had no effect, concentrations as low as 10 μM DBA prevented apoptosis in both scramble and Cx43 (−) cells (Figure 1D), validating that DBA is equally effective in preventing apoptosis of cells expressing or lacking Cx43. Furthermore, PTH and DBA used at higher concentrations (100 nM and 150 μM, respectively), in order to maximize the response in terms of gene transcription, induced the expression of IL-6, RANKL, c-fos and Nur77, recognized cAMP-target genes (Tetradis et al., 2001) in Cx43(+) cells. In contrast, only DBA had a significant effect in Cx43(−) cells, although to a lesser extent compared to its effect in Cx43(+) cells (Figure 1E).

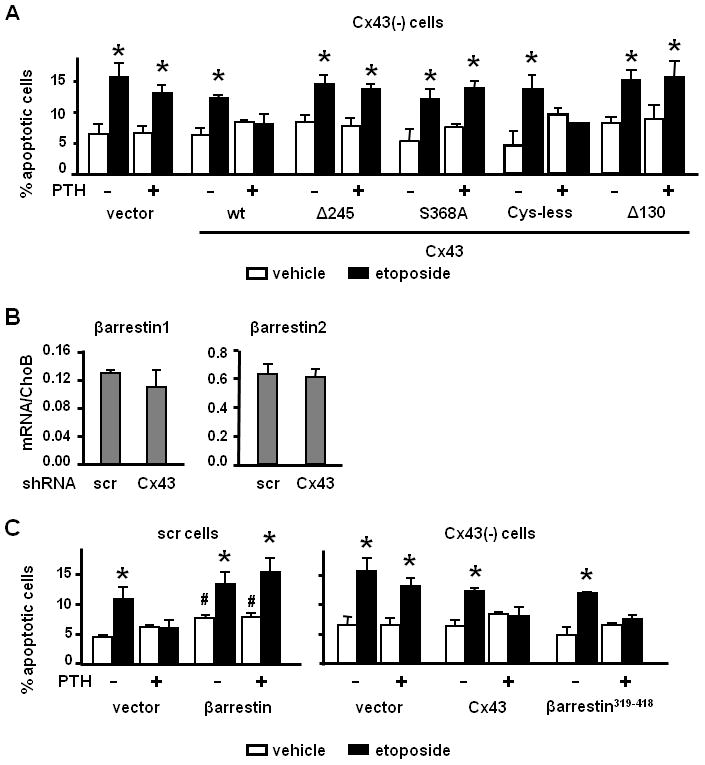

PTH-induced osteoblast survival requires phosphorylation of serine 368 within the cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 and it is abolished by overexpression of βarrestin

Expression of full length wild type Cx43 rescued responsiveness to PTH in Cx43(−) cells (Figure 2A). The cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 containing the C-terminus has been shown to have regulatory functions, to interact with structural and signaling molecules (Giepmans, 2004), and to be required for the anti-apoptotic effect of bisphosphonates on osteoblastic cells (Plotkin et al., 2002). We therefore investigated whether this domain was responsible for rescuing the anti-apoptotic effect of PTH. We found that the Cx43 mutant lacking the cytoplasmic C-terminus domain Cx43Δ245 was not able to confer responsiveness to PTH in Cx43(−) cells. Several residues have been described in the C-terminus of Cx43 that are important for Cx43-mediated functions. We focused our attention on serine 368, since the phosphorylation at this residue has been implicated in crucial events, such as Cx43 trafficking, plaque assembly, and regulation of channel activity. We found that elimination of the phosphorylation site at serine 368 (Cx43S368A), abolished the ability of Cx43 to rescue the responsiveness to PTH. This suggests that phosphorylation of serine 368 in the cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 is required for prevention of osteoblast apoptosis by PTH. We then investigated whether gap junction communication or hemichannels activity was required for PTH-mediated survival. A Cx43 mutant that lacks six cysteines in the extracellular domain responsible for the docking between juxtaposed channels (Cx43cys-less) able to form active hemichannels, but not gap junctions, restored PTH responsiveness in Cx43(−) cells (Figure 2A). On the other hand, cells expressing a Cx43 mutant with impaired channel permeability (Cx43Δ130) were not responsive to PTH-mediated survival signaling.

Figure 2. PTH-induced osteoblast survival requires phosphorylation of serine 368 within the cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 and it is abolished by overexpression of βarrestin.

(A) Cx43-deficient cells were transiently transfected with the indicated constructs. Forty hours after transfection, apoptosis was assayed as detailed under Experimental Procedures. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cultures. (B) mRNA expression levels of βarrestin1 and 2 in scr and Cx43-deficient cells. (C) Scr and Cx43(−) cells were transiently transfected with wild type βarrestin1 and wild type Cx43 or βarrestin1319–418, respectively, along with nGFP. Apoptosis was determined by evaluating nuclear morphology of transfected (fluorescent) cells as described in Experimental Procedures. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of triplicate determinations. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cultures; # p<0.05 versus vector-transfected, vehicle-treated scramble cells.

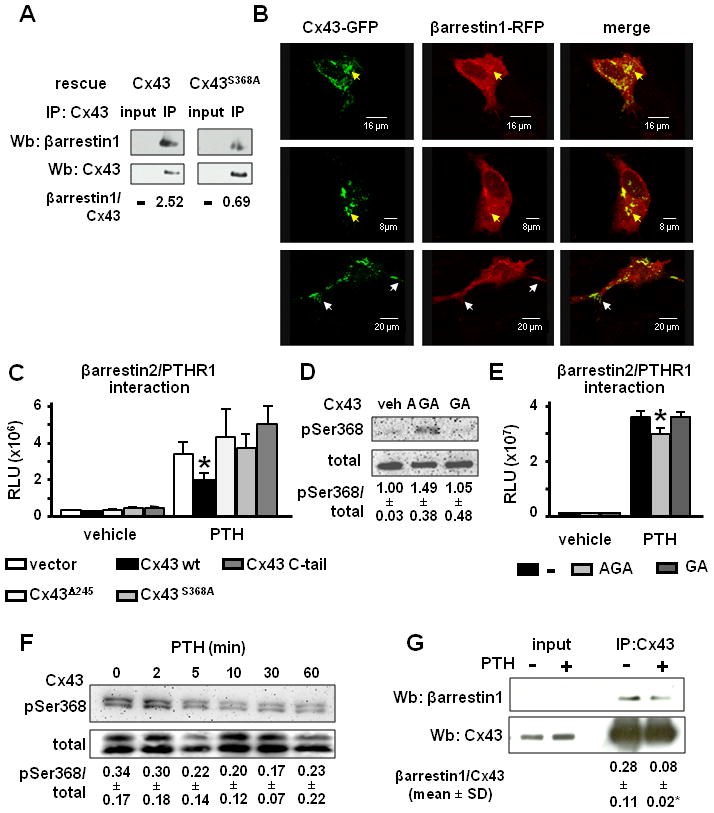

Cx43 physically associates with βarrestin through phosphorylated serine 368

Previous evidence indicates that βarrestins 1 and 2, highly homologous scaffolding proteins that bind G protein-coupled receptors, are responsible for suppressing PTH-induced cAMP production (Castro et al., 2002) and for inducing internalization of the PTHR1 (Ferrari et al., 2005;Ferrari and Bisello, 2001;Vilardaga et al., 2001). Based on this, and on evidence from our laboratory showing that Cx43 interacts with βarrestin1 in osteocytic cells (Plotkin et al., 2006), we explored the possibility that βarrestin association with Cx43 was responsible for the modulation of the anti-apoptotic effect of PTH by Cx43.

OB-6 osteoblastic cells express both isoforms of βarrestin, 1 and 2; and their expression was not significantly altered by silencing Cx43 (Figure 2B). Overexpression of βarrestin1 induced a small but significant increase in apoptosis in the absence of etoposide and independently of the presence of P T H (Figure 2C). Importantly, βarrestin1 overexpression abolished the survival effect of PTH in cells expressing Cx43. Moreover, in cells lacking Cx43, the response to PTH was recovered by a dominant negative form of βarrestin that consists solely of the clathrin binding domain (βarrestin319–418), which has been shown to block PTHR1 internalization (Sneddon and Friedman, 2007) and to interfere with the action of βarrestins (DeFea et al., 2000a;Ge et al., 2003;Sneddon and Friedman, 2007).

To determine whether Cx43 interacts with βarrestin, we immunoprecipitated Cx43 in total protein lysates from Cx43-deficient cells transfected with wild type Cx43. We found that the anti-Cx43 antibodies pulled down βarrestin1 (Figure 3A). In addition, when the Cx43S368A mutant was transfected instead of wild type Cx43, the ratio of immunoprecipitated βarrestin1/Cx43 was decreased from 2.52 to 0.69 (a 4-fold decrease). An additional experiment showed a similar decrease. The small amount of βarrestin immunoprecipitated in the presence of the mutant Cx43S368A might result from the presence of residual wild type Cx43 still expressed in Cx43(−) cells. These results indicate that Cx43 physically associates with βarrestin1 and that phosphorylation of Cx43 in serine 368 is important for the interaction between the two proteins. As a complementary approach to demonstrate physical association, we performed confocal microscopy of Cx43-deficient cells co-transfected with Cx43 fused to GFP and βarrestin1 fused to RFP. Overlay of the green and red images showed discrete areas in the cytoplasm displaying yellow color, indicating co-localization of Cx43-GFP and βarrestin1-RFP (Figure 3B and Supplementary figure 1). Interestingly, the two proteins also co-localize in areas at which membranes of adjacent cells are in contact (such as the one shown in Supplementary figure 1, lower panels), suggesting that βarrestin could also associate with the pool of Cx43 molecules involved in cell-to-cell communication through gap junctions.

Figure 3. βarrestin association with Cx43 or the PTHR1 is modulated by Cx43S368 phosphorylation.

(A) Cx43-deficient cells transfected with wild type Cx43 or Cx43S368A were lysed and total protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cx43 antibodies. Western blot was performed with anti-Cx43 and anti-βarrestin1 antibodies. Bands were analyzed by densitometry and the ratio between immunoprecipitated βarrestin1 and Cx43 was calculated. (B) Representative images showing the sub-cellular distribution of Cx43-GFP and βarrestin1-RFP analyzed by confocal microscopy in wild type OB-6 cells transiently transfected with the indicated constructs. Yellow and white arrows point at areas of co-localization of the two proteins in the cytoplasm and the plasma membrane, respectively. (C) CHO cells were transfected with the indicated constructs and βarrestin binding to the PTHR1 was assayed as detailed in the Experimental Procedures section. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of six wells independently transfected. * p < 0.05 versus vector-transfected cells. Similar results were reproduced in two additional independent experiments. (D) 100 μM AGA, GA or DMSO as vehicle were added for 30 min to OB-6 cells and the levels of phosphorylated Cx43S368 (pSer368) were evaluated by Western blotting. Bands were analyzed by densitometry and the ratio between pSer368 and total Cx43 was calculated. Values represent mean ± S.D. of three replicas. (E) CHO cells were treated with 100 μM AGA, GA or DMSO as vehicle 30 min prior to the addition of 50 nM PTH for 90 min. βarrestin binding to the PTH receptor was assayed as detailed in the Experimental Procedures section. Bars represent mean ± S.D. of six wells independently treated. * p < 0.05 versus vector-transfected cells. Similar results were reproduced in two additional independent experiments (F) 50 nM PTH was added for the indicated time points to wild type OB-6 cells and phosphorylation of Cx43S368 was evaluated by Western blotting on total protein extracts. Bands were analyzed by densitometry and the ratio between pSer368 and total Cx43 was calculated. Values correspond to mean ± S.D. of three replicas. (G) Cx43-deficient cells transfected with wild type Cx43 were treated with 50 nM PTH or vehicle for 5 min. Cells were lysed and total protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cx43 antibodies. Western blot was performed with anti-Cx43 and anti-βarrestin1 antibodies. Bands were analyzed by densitometry and the ratio between immunoprecipitated βarrestin1 and Cx43 was calculated. The mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. * p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated cells.

Cx43 expression and its phosphorylation in serine 368 interfere with the association of βarrestin with PTHR1

We next questioned whether association with Cx43 affected the recognized interaction of βarrestins with the PTHR1. Towards this end, we employed an assay in which CHO cells, which express Cx43 (not shown), are stably transfected with one fragment of the β-galactosidase enzyme fused to the PTHR1 and another fused to βarrestin2. PTH induced the expected interaction between PTHR1 and βarrestin2 in cells transfected with vector, as evidenced by a 5.8-fold increase in relative luminescence units resulting from the association of the two β-galactosidase fragments to form the active enzyme (Figure 3C). In cells transfected with wild type Cx43, PTH-induced β-galactosidase activity was reduced by 40%. Since only about 50% of CHO cells are transfected, the decreased enzymatic activity is consistent with a strong inhibition of the interaction in the transfected cells. On the other hand, PTH induced similar PTHR1/βarrestin2 interaction in cells expressing the mutated forms Cx43Δ245 or Cx43S368A compared to vector-transfected cells. Moreover, transfection of the C-terminus of Cx43 alone did not interfere with the interaction between PTHR1 and βarrestin2; suggesting that intact Cx43 is required to prevent PTHR1/βarrestin2 association. Similar results were reproduced in two additional independent experiments. These findings suggested that Cx43 decreases the interaction between PTHR1 and βarrestin by binding to βarrestin through phosphorylated serine 368.

To directly test this possibility, we examined the effect of phosphorylating Cx43 in serine 368 with glycyrrhetinic acid, AGA (Liang et al., 2008), on PTHR1/βarrestin2 interaction. We found that AGA increased the phosphorylation of Cx43 in serine 368 in OB-6 cells, whereas the inactive analog GA had no effect (Figure 3D). Moreover, AGA treatment resulted in a small, but significant reduction in PTH-induced PTHR1/βarrestin2 interaction, compared to cells treated with the inactive analog GA or to untreated cells (Figure 3E). The low solubility and high toxicity of AGA and GA precluded their use at higher concentrations that could have resulted in stronger effects. Nevertheless, the modest increase in Cx43 phosphorylation inversely correlated to the extent of inhibition of PTHR1/βarrestin interaction. Taken together, these results suggest that Cx43 sequesters βarrestins through phosphoserine 368 in its cytoplasmic C-terminal domain, reducing the pool of βarrestin available to associate with the PTHR1.

We next determined whether changes in the phosphorylation status of serine 368 of Cx43 contribute to binding of βarrestin to the PTHR1 induced by PTH. We found that PTH caused a time-dependent decrease in the levels of phosphorylated Cx43S368, reaching a minimum after 30 min of addition of the hormone to OB-6 cells (Figure 3F). In addition, and consistent with the requirement of phosphorylation of Cx43 in serine 368 for its binding to βarrestin, PTH also caused a significant reduction in the amount of βarrestin pulled down by anti-Cx43 antibodies (Figure 3G). Taken together, these findings suggest that PTH induces Cx43 dephosphorylation and the release of βarrestin from its interaction with Cx43, thereby increasing the pool of βarrestin available to bind to the PTHR1.

DISCUSSION

The studies reported herein demonstrate that Cx43 expression is indispensable for the survival effect of PTH on osteoblastic cells. Considering that bone anabolism induced by intermittent PTH administration is associated with inhibition of osteoblast apoptosis, our findings provide an explanation for why mice lacking Cx43 in osteoblasts and osteocytes exhibit reduced response to PTH (Chung et al., 2006). Nevertheless, future studies are required to establish whether indeed osteoblasts from Cx43-deficient mice are refractory to the survival effect of PTH.

Cx43 is required for the early steps of PTHR1 signaling leading to the transcription of cAMP-dependent genes, as evidenced by the ability of the stable cAMP analog DBA to circumvent the requirement of Cx43 for gene transcription and anti-apoptosis. The lower effect of DBA on cAMP-target gene expression observed in Cx43 deficient cells could be due to the fact that a full response to cAMP might require cooperation between cAMP signaling and other signaling pathways known to be activated downstream of the PTHR1, such as ERKs and Wnt signaling. The fact that DBA is able to fully mimic the response of PTH in Cx43 expressing cells but not in Cx43 deficient cells indicates that Cx43 (−) cells lack some of these additional factors required for a full response in gene expression. Remarkably, DBA faithfully mimics the response to PTH regarding anti-apoptosis even in Cx43 (−) cells, indicating that the cAMP pathway is sufficient to trigger survival signaling.

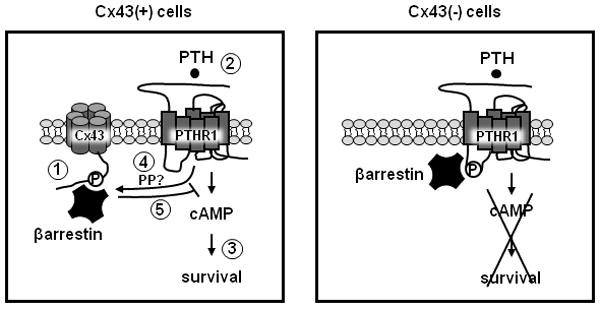

Based on our findings, we propose the sequence of events depicted in Figure 4. In Cx43-expressing osteoblasts, a pool of βarrestin is sequestered by its interaction with phosphorylated serine 368 within the cytoplasmic domain of Cx43, allowing PTH-dependent pro-survival signaling downstream of cAMP. PTH also induces the dephosphorylation of Cx43, likely by activating protein phosphatases. This leads to the release of βarrestin from Cx43, binding of βarrestin to the PTHR1, inhibition of cAMP production, and internalization of PTHR1. In Cx43-deficient osteoblasts, a larger pool of βarrestin is available to bind to PTHR1, thus blunting cAMP accumulation, transcription of cAMP target genes, and survival signaling induced by PTH. Similar to our findings with Cx43, it has been recently shown that sequestration of βarrestin by binding to the Na+/H+ exchange regulatory factor 1, NHERF1, interferes with PTHR1/βarrestin interaction (Wang et al., 2009).

Figure 4. Working model.

In Cx43-expressing osteoblasts [Cx43(+) cells], a pool of βarrestin is sequestered by its interaction with phosphorylated serine 368 within the cytoplasmic domain of Cx43 (1), allowing PTH-dependent pro-survival signaling downstream of cAMP (2 and 3). PTH also induces the dephosphorylation of Cx43, likely by activating a protein phosphatase (PP) (4). This leads to the release of βarrestin from Cx43, binding of βarrestin to the PTHR1, inhibition of cAMP production, and internalization of PTHR1 (5). In Cx43-deficient osteoblasts [Cx43(−) cells], a larger pool of βarrestin is available to bind to PTHR1, thus blunting cAMP accumulation, transcription of cAMP target genes, and survival signaling induced by PTH.

Previous studies have identified several proteins that bind to the C-terminus domain of Cx43 and regulate Cx43 cellular trafficking, its phosphorylation, and the formation and gating of gap junctions (Giepmans, 2004). In turn, through protein-protein interactions, Cx43 regulates intracellular signaling. By binding to zona occludens protein 1, ZO-1, and directly to microtubules, Cx43 controls cytoskeletal organization in several cell types, including glioma cells (Crespin et al., 2010) and breast cancer cells (Sin et al., 2009). Moreover, we have shown that in osteoblastic cells Cx43 interaction with the kinase Src results in activation of the ERK pathway and induction of cell survival (Plotkin et al., 2002). Our current studies reveal that βarrestin is another partner of Cx43 in osteoblastic cells through which Cx43 modulates cAMP signaling downstream of the PTH receptor.

The immunoprecipitation experiments and confocal imaging suggest that βarrestin1 and Cx43 co-localize not only at the cell membrane, but also in the cytoplasm. This evidence is consistent with previous studies that detected Cx43 in both cellular compartments (Lampe and Lau, 2000;Valiunas et al., 2001) and suggests that Cx43 physically associates with βarrestin during trafficking of the protein from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane. However, transfection of the C-terminus of Cx43 alone is not sufficient to interfere with PTHR1/βarrestin binding. This can be attributed to the inability of the C-terminus to localize in the plasma membrane unless is co-transfected with the transmembrane domain of Cx43 (Dang et al., 2003) and suggests that the membrane localization of the complex Cx43/βarrestin is required in order to allow PTHR1-mediated survival signaling.

The dominant negative βarrestin319–418 mutant was used as a tool to interfere with βarrestin function. The mechanism of action of this protein is not completely understood. Indeed, this βarrestin mutant might inhibit or not PTHR1 internalization depending on the cell context (Sneddon and Friedman, 2007;Syme et al., 2005). In addition, βarrestin319–418 blocks PTH-induced ERK activation (Syme et al., 2005). In OB-6 osteoblastic cells, we found that this dominant negative reverses the effect of endogenous βarrestin by conferring responsiveness to PTH in the absence of Cx43. Whether this action is due to inhibition of PTHR1 stabilization or to other functions of βarrestin potentially relevant for the survival effect of PTH will require future studies.

Two isoforms of βarrestin have been described, 1 and 2, that share 75% homology (Attramadal et al., 1992). Notably, although βarrestin1 is less efficient than βarrestin2 in promoting PTHR1 internalization (Sneddon and Friedman, 2007), both equally suppress cAMP production induced by PTH (Castro et al., 2002). Moreover, deletion of either βarrestin1 or 2 abolishes PTH-induced sustained ERK activation, suggesting a similar mechanism of action of both isoforms (Gesty-Palmer et al., 2006). Consistent with this evidence, the current study suggests that Cx43 regulates PTHR1 signaling associating with either βarrestin1 or 2.

We also demonstrate that serine 368 is the specific site in the C-terminus domain of Cx43 responsible for its interaction with βarrestin. Although phosphorylation of this amino acid has been previously shown to modulate Cx43 channel gating (Giepmans, 2004), to our knowledge our study is the first to propose its participation in the scaffolding function of Cx43. Moreover, Cx43S368 is phosphorylated by several stimuli that induce activation of protein kinase C, including phorbol esters (Lampe et al., 2000), agonists of the δ opiod receptor (Miura et al., 2007), and during wound healing (Richards et al., 2004), with the consequent closure of connexin channels. Although it has been proposed that PKA mediates the increase in phospho-Cx43S368 induced by the follicle-stimulating hormone (Yogo et al., 2002), a direct effect of the kinase in the phosphorylation of this residue has not been demonstrated. Our findings that PTH reduces the levels of phosphorylated Cx43S368 suggest that the hormone activates a serine phosphatase. Consistent with this, PTH enhances the activation of PPA2 in human colon Caco-2 cells (Calvo et al., 2010). Moreover, Cx43 co-localizes with protein phosphatases such as PP1 and PPA2 in ventricular myocytes (Duthe et al., 2001;Ai and Pogwizd, 2005), raising the possibility that PTH induces the activation of a Cx43-bound phosphatase resulting in the dephosphorylation of the connexin. In addition, phosphorylation of serine 365 in Cx43 induced by PKA inhibits protein kinase C phosphorylation in serine 368 (Solan and Lampe, 2009), suggesting another potential mechanism for the reduction of phosphorylated Cx43S368 induced by PTH in osteoblastic cells.

In earlier studies, PTH has been reported to stimulate cell coupling through gap junctions by a mechanism that does not require new protein synthesis (Civitelli et al., 1998). Although this phenomenon has been ascribed to a positive effect of PTH on the assembly of new plaques, we cannot rule out the possibility that the enhancement of cell-to-cell communication is due to channel opening via dephosphorylation of serine 368. Indeed, previous evidence indicates that hemichannel permeability is diminished by phosphorylation of Cx43S368, through a conformational change of the protein (Bao et al., 2004). The finding that Cx43 channel permeability is indeed required for PTH-induced survival further indicates that hemichannels opening may play a role in the interaction between Cx43 and βarrestin and in PTH survival signaling. This may also explain ability of Cx45 to abolish PTH-induced survival; thus, Cx45, harboring a different C-terminus, might not bind βarrestin as efficiently as Cx43, and might also reduce channel permeability. Whether indeed reduction in Cx43S368 phosphorylation by PTH results in Cx43 channel opening in osteoblastic cells will require future investigations.

In conclusion, our findings reveal a novel scaffolding function of the cytoplasmic C-terminus domain of Cx43, through which the connexin plays a permissive role on cAMP-mediated osteoblast survival induced by PTH. We propose that in the presence of Cx43, the pool of βarrestin bound to the PTHR1 is reduced, thereby allowing cAMP production and survival signaling (Figure 4). Subsequently, PTH induces the dephosphorylation of Cx43 and the release of βarrestin, which then binds to the PTHR1, turning off downstream signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health and the National Osteoporosis Foundation.

Contract grant number: R01-AR053643 to LIP and KO2-AR02127, R03 TW006919, and R01-DK076007 to TB and 2007 NOF Research Grants Program to LIP

The authors thank Kanan Vyas, Gianluca Frera, Racheal Lee, and Jeffrey Benson for technical assistance; and DiscoverX Corporation for providing the PathHunter eXpress βarrestin GPCR Kits and for technical support. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-AR053643 to LIP and KO2-AR02127, R03 TW006919, and R01-DK076007 to TB) and by the National Osteoporosis Foundation (2007 NOF Research Grants Program to LIP).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR1, PTH receptor 1; PTHrP, PTH-related protein; cAMP, cyclic AMP; PKA, protein kinase A; Cx43, connexin43; DBA, dibutyryl cAMP; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; AGA, α-glycyrrhetinic acid; GA, glycyrrhizic acid.

References

- Ai X, Pogwizd SM. Connexin 43 downregulation and dephosphorylation in nonischemic heart failure is associated with enhanced colocalized protein phosphatase type 2A. Circ Res. 2005;96:54–63. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000152325.07495.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attramadal H, Arriza JL, Aoki C, Dawson TM, Codina J, Kwatra MM, Snyder SH, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin2, a novel member of the arrestin/beta-arrestin gene family. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17882–17890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Reuss L, Altenberg GA. Regulation of purified and reconstituted connexin 43 hemichannels by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of Serine 368. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20058–20066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido T, Ali AA, Plotkin LI, Fu Q, Gubrij I, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, O’Brien CA, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Proteasomal degradation of Runx2 shortens parathyroid hormone-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in osteoblasts. A putative explanation for why intermittent administration is needed for bone anabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50259–50272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer EC, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Connexin family of gap junction proteins. J Membr Biol. 1990;116:187–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01868459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Sims NA, Hunzelman JL, Knight MC, Giovannetti A, Saxton JM, Kronenberg HM, Baron R, Schipani E. Activated parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor in osteoblastic cells differentially affects cortical and trabecular bone. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:277–286. doi: 10.1172/JCI11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo N, de Boland AR, Gentili C. PTH inactivates the AKT survival pathway in the colonic cell line Caco-2. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro M, Dicker F, Vilardaga JP, Krasel C, Bernhardt M, Lohse MJ. Dual Regulation of the Parathyroid Hormone (PTH)/PTH-Related Peptide Receptor Signaling by Protein Kinase C and βarrestins. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3854–3865. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D, Castro CH, Watkins M, Stains JP, Chung MY, Szejnfeld VL, Willecke K, Theis M, Civitelli R. Low peak bone mass and attenuated anabolic response to parathyroid hormone in mice with an osteoblast-specific deletion of connexin43. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4187–4198. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civitelli R. Cell-cell communication in the osteoblast/osteocyte lineage. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civitelli R, Ziambaras K, Warlow PM, Lecanda F, Nelson T, Harley J, Atal N, Beyer EC, Steinberg TH. Regulation of connexin43 expression and function by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and parathyroid hormone (PTH) in osteoblastic cells. J Cell Biochem. 1998;68:8–21. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19980101)68:1<8::aid-jcb2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespin S, Bechberger J, Mesnil M, Naus CC, Sin WC. The carboxy-terminal tail of connexin43 gap junction protein is sufficient to mediate cytoskeleton changes in human glioma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110:589–597. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang X, Doble BW, Kardami E. The carboxy-tail of connexin-43 localizes to the nucleus and inhibits cell growth. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;242:35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFea KA, Vaughn ZD, O’Bryan EM, Nishijima D, Dery O, Bunnett NW. The proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of substance P are facilitated by formation of a beta -arrestin-dependent scaffolding complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000a;97:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190276697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFea KA, Zalevsky J, Thoma MS, Dery O, Mullins RD, Bunnett NW. Beta-arrestin-dependent endocytosis of proteinase-activated receptor 2 is required for intracellular targeting of activated ERK1/2. J Cell Biol. 2000b;148:1267–1281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthe F, Plaisance I, Sarrouilhe D, Herve JC. Endogenous protein phosphatase 1 runs down gap junctional communication of rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1648–C1656. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.5.C1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari SL, Behar V, Chorev M, Rosenblatt M, Bisello A. Endocytosis of ligand-human parathyroid hormone receptor 1 complexes is protein kinase C-dependent and involves beta-arrestin2. Real-time monitoring by fluorescence microscopy. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29968–29975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari SL, Bisello A. Cellular distribution of constitutively active mutant parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related protein receptors and regulation of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate signaling by beta-arrestin2. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:149–163. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.1.0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari SL, Pierroz DD, Glatt V, Goddard DS, Bianchi EN, Lin FT, Manen D, Bouxsein ML. Bone response to intermittent parathyroid hormone is altered in mice null for beta-Arrestin2. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1854–1862. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge L, Ly Y, Hollenberg MD, DeFea K. A beta-arrestin-dependent scaffold is associated with prolonged MAPK activation in pseudopodia during protease-activated receptor-2 induced chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34418–34426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesty-Palmer D, Chen M, Reiter E, Ahn S, Nelson CD, Loomis CR, Spurney RF, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Distinct beta-arrestin and G protein dependent pathways for parathyroid hormone receptor stimulated ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10856–10864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giepmans BN. Gap junctions and connexin-interacting proteins. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Beyond the gap: functions of unpaired connexon channels. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:285–294. doi: 10.1038/nrm1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, Dian L, Hanley DA, Harris ST, Kendler DL, McClung MR, Miller PD, Olszynski WP, Orwoll E, Yuen CK. Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:688–703. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilka RL. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40:1434–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Bellido T, Roberson P, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC. Increased bone formation by prevention of osteoblast apoptosis with parathyroid hormone. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:439–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyel PA, Thieman JR, Roth R, Erkan E, Everett ET, Watkins SC, Heuser JE, Traub LM. The AP-2 adaptor beta2 appendage scaffolds alternate cargo endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5309–5326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousteni S, Bellido T, Plotkin LI, O’Brien CA, Bodenner DL, Han L, Han K, Di Gregorio GB, Katzenellenbogen JA, Katzenellenbogen BS, Roberson PK, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Manolagas SC. Nongenotropic, sex-nonspecific signaling through the estrogen or androgen receptors: dissociation from transcriptional activity. Cell. 2001;104:719–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutovskikh VA, Yamasaki H, Tsuda H, Asamoto M. Inhibition of intrinsic gap-junction intercellular communication and enhancement of tumorigenicity of the rat bladder carcinoma cell line BC31 by a dominant-negative connexin 43 mutant. Mol Carcinog. 1998;23:254–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe PD, Lau AF. Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:205–215. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe PD, TenBroek EM, Burt JM, Kurata WE, Johnson RG, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368 by protein kinase C regulates gap junctional communication. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1503–1512. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecanda F, Towler DA, Ziambaras K, Cheng SL, Koval M, Steinberg TH, Civitelli R. Gap junctional communication modulates gene expression in osteoblastic cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2249–2258. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecka-Czernik B, Gubrij I, Moerman EA, Kajkenova O, Lipschitz DA, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Inhibition of Osf2/Cbfa1 expression and terminal osteoblast differentiation by PPAR-gamma 2. J Cell Biochem. 1999;74:357–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang JY, Wang SM, Chung TH, Yang SH, Wu JC. Effects of 18-glycyrrhetinic acid on serine 368 phosphorylation of connexin43 in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. Cell Biol Int. 2008;32:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ. Osteoblast-derived PTHrP is a physiological regulator of bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2322–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI26239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao D, He B, Jiang Y, Kobayashi T, Soroceanu MA, Zhao J, Su H, Tong X, Amizuka N, Gupta A, Genant HK, Kronenberg HM, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Osteoblast-derived PTHrP is a potent endogenous bone anabolic agent that modifies the therapeutic efficacy of administered PTH 1–34. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2402–2411. doi: 10.1172/JCI24918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Yano T, Naitoh K, Nishihara M, Miki T, Tanno M, Shimamoto K. Delta-opioid receptor activation before ischemia reduces gap junction permeability in ischemic myocardium by PKC-epsilon-mediated phosphorylation of connexin 43. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1425–H1431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01115.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CA, Plotkin LI, Galli C, Goellner J, Gortazar AR, Allen MR, Robling AG, Bouxsein M, Schipani E, Turner CH, Jilka RL, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Control of bone mass and remodeling by PTH receptor signaling in osteocytes. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin LI, Aguirre JI, Kousteni S, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Bisphosphonates and estrogens inhibit osteocyte apoptosis via distinct molecular mechanisms downstream of ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7317–7325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin LI, Lezcano V, Thostenson J, Weinstein RS, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Connexin 43 is required for the anti-apoptotic effect of bisphosphonates on osteocytes and osteoblasts in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1712–1721. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin LI, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Transduction of cell survival signals by connexin-43 hemichannels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8648–8657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin LI, Vyas K, Gortazar AR, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. βarrestin complexes with connexin (Cx) 43 and anchors ERKs outside the nucleus: a requirement for the Cx43/ERK-mediated anti-apoptotic effect of bisphosphonates in osteocytes. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:S65. [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin LI, Weinstein RS, Parfitt AM, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC, Bellido T. Prevention of osteocyte and osteoblast apoptosis by bisphosphonates and calcitonin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1363–1374. doi: 10.1172/JCI6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premont RT, Gainetdinov RR. Physiological roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:511–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards TS, Dunn CA, Carter WG, Usui ML, Olerud JE, Lampe PD. Protein kinase C spatially and temporally regulates gap junctional communication during human wound repair via phosphorylation of connexin43 on serine368. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:555–562. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe W, Veitch GI, Gong XQ, Pellegrino E, Bai D, McLachlan E, Shao Q, Kidder GM, Laird DW. Oculodentodigital dysplasia-causing connexin43 mutants are non-functional and exhibit dominant effects on wild-type connexin43. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11458–11466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin WC, Tse M, Planque N, Perbal B, Lampe PD, Naus CC. Matricellular protein CCN3 (NOV) regulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29935–29944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.042630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon WB, Friedman PA. Beta-arrestin-dependent parathyroid hormone-stimulated extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor internalization. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4073–4079. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solan JL, Lampe PD. Connexin43 phosphorylation: structural changes and biological effects. Biochem J. 2009;419:261–272. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg TH, Civitelli R, Geist ST, Robertson AJ, Hick E, Veenstra RD, Wang HZ, Warlow PM, Westphale EM, Laing JG. Connexin43 and connexin45 form gap junctions with different molecular permeabilities in osteoblastic cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:744–750. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme CA, Friedman PA, Bisello A. Parathyroid hormone receptor trafficking contributes to the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases but is not required for regulation of cAMP signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11281–11288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetradis S, Bezouglaia O, Tsingotjidou A, Vila A. Regulation of the nuclear orphan receptor Nur77 in bone by parathyroid hormone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;281:913–916. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong D, Li TY, Naus KE, Bai D, Kidder GM. In vivo analysis of undocked connexin43 gap junction hemichannels in ovarian granulosa cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4016–4024. doi: 10.1242/jcs.011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiunas V, Gemel J, Brink PR, Beyer EC. Gap junction channels formed by coexpressed connexin40 and connexin43. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1675–H1689. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Molen MA, Rubin CT, McLeod KJ, McCauley LK, Donahue HJ. Gap junctional intercellular communication contributes to hormonal responsiveness in osteoblastic networks. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12165–12171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilardaga JP, Frank M, Krasel C, Dees C, Nissenson RA, Lohse MJ. Differential conformational requirements for activation of G proteins and the regulatory proteins arrestin and G protein-coupled receptor kinase in the G protein-coupled receptor for parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33435–33443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Yang Y, Abou-Samra AB, Friedman PA. NHERF1 regulates parathyroid hormone receptor desensitization: interference with beta-arrestin binding. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:1189–1197. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.054486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogo K, Ogawa T, Akiyama M, Ishida N, Takeya T. Identification and functional analysis of novel phosphorylation sites in Cx43 in rat primary granulosa cells. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:132–136. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Kasperek EM, Nicholson BJ. Dissection of the molecular basis of pp60(v-src) induced gating of connexin 43 gap junction channels. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:1033–1045. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.5.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.