Abstract

The adaptor protein ASC contributes to innate immunity through the assembly of caspase-1-activating inflammasome complexes. We demonstrate that ASC plays an inflammasome-independent cell-intrinsic role in adaptive immune cells. Asc−/− mice displayed defective antigen presentation by dendritic cells and lymphocyte migration due to impaired Rac-mediated actin polymerization. Genome-wide analysis showed that ASC, but not Nlrp3 or caspase-1, controls mRNA stability and expression of DOCK2, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that mediates Rac-dependent signaling in immune cells. DOCK2-deficient dendritic cells showed similar defective antigen uptake as Asc−/− cells. Ectopic expression of DOCK2 in ASC-deficient cells restored Rac-mediated actin polymerization, antigen uptake and chemotaxis. Thus, ASC shapes adaptive immunity independently of inflammasomes by modulating DOCK2-dependent Rac activation and F-actin polymerization in dendritic cells and lymphocytes.

Keywords: ASC, caspase-1, inflammasome, NLR, TLR, DOCK2, antigen uptake

Introduction

Inflammasomes are intracellular multi-protein complexes that are emerging as key regulators of the innate immune response. Deregulated inflammasome activity has been linked to autoimmune diseases including inflammatory bowel diseases1-5, vitiligo6, gouty arthritis7, type I and type II diabetes8, 9, and less common autoinflammatory disorders that are collectively referred to as cryopyrinopathies10, 11. Distinct inflammasome complexes are assembled around members of the NOD-like receptor (NLR) or HIN-200 families in a pathogen-specific manner12-14. The NLR protein Nlrc4 assembles an inflammasome in macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens such as Salmonella typhimurium, Legionella pneumophila, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Shigella flexneri15-22. In contrast, Bacillus anthracis Lethal Toxin (LT) triggers activation of the Nlrp1b inflammasome in mouse macrophages and mutations in the Nlrp1b gene were identified as the key susceptibility locus for anthrax LT-induced macrophage death23. The NLR protein Nlrp3 mediates caspase-1 activation in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-primed macrophages that are exposed to microbial components with diverse molecular structures such as viral RNA and DNA, microbial toxins such as the ionophore nigericin17, 24-27. In addition, the endogenous danger-associated molecules monosodium urate (MSU) and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate (CPPD) crystals also activate the Nlrp3 inflammasome, suggesting a role for this inflammasome in the etiology of gouty arthritis and pseudogout7. The Nlrp3 inflammasome contributes to host defense against Salmonella infection in vivo28. Moreover, previous reports characterized the critical role of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in protection against colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis2, 3, 5. Finally, DNA viruses such as vaccinia and cytomegalovirus and the bacterial pathogens Francisella tularensis and Listeria monocytogenes induce caspase-1 activation through the recently identified HIN-200 family member AIM2 (refs. 29-34). Once activated, caspase-1 cleaves and allows secretion of bioactive interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. In addition, caspase-1 mediates a specialized form of cell death in infected macrophages and dendritic cells, a process that contributes significantly to the pathophysiology of several infectious diseases12, 35.

Until recently, the adaptor molecule apoptosis-associated speck like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC, also known as Pycard) was believed to exert its effects on immune signaling primarily by bridging the interaction between NLRs and HIN-200 proteins and caspase-1 in inflammasome complexes36, 37. However, evidence is emerging that point to important inflammasome-independent roles of ASC in controlling immune responses. For instance, adjuvanticity of the oil-in-water emulsion MF59 was recently shown to require ASC, whereas the inflammasome components Nlrp3 and caspase-1 were dispensable38. Consequently, the induction of antigen-specific gamma immunoglobulins (IgGs) against MF59-adjuvanted influenza vaccines was impaired in mice lacking ASC, but not in Nlrp3−/− or caspase-1−/− mice38. Moreover, granuloma formation and host defense in chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection depended on ASC, but not on Nlrp3 or caspase-1 (ref. 39). Finally, Asc−/− mice, but not Nlrp3−/− or caspase-1−/− mice, were significantly protected against disease progression in experimental models of rheumatoid arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), respectively40-42. The latter studies pointed to the existence of cell-intrinsic roles of ASC in dendritic cell and lymphocyte populations. However, the molecular effector mechanism by which ASC regulates adaptive immune responses independently of inflammasomes has remained enigmatic.

Here we show that ASC plays a critical cell-intrinsic role in regulating immune cell functions in lymphocytes and dendritic cells in an inflammasome-independent manner. Chemotaxis of Asc−/− lymphocytes, but not those lacking Nlrp3 or caspase-1, was significantly impaired despite normal chemokine receptor expression and downstream MAPK signaling. Instead, ASC-deficient lymphocytes failed to migrate due to defective Rac-induced actin polymerization at the leading edge of leukocytes. Consequently, total lymphocyte and dendritic cell populations in secondary lymphoid organs were significantly reduced in Asc−/−, but not in Nlrp3−/− or caspase-1−/− mice. Rac activation and actin polymerization plays a critical role in other cell type functions as well, including the uptake of antigens by dendritic cells43. Accordingly, ASC-deficient dendritic cells were impaired in their ability to take up antigens and to drive T cell proliferation. Again, inflammasome signaling was dispensable for ASC-mediated antigen presentation and T cell activation. Instead, transcriptome analysis revealed ASC to specifically regulate transcript abundance of Dedicator of cytokinesis 2 (DOCK2), an immune cell-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor that mediates Rac-dependent actin polymerization and migration of T and B cells44. As in Asc−/− cells, we identified a critical role for DOCK2 in antigen uptake by dendritic cells. Moreover, ectopic expression of DOCK2 in Asc−/− lymphocytes and dendritic cells restored ASC-dependent immune functions, confirming that DOCK2 is the main effector driving the inflammasome-independent functions of ASC in immune cells. Thus, ASC regulates adaptive immune responses by controlling DOCK2 expression in dendritic cells and lymphocytes. These results uncover a novel mechanism regulating adaptive immune cell functions and provide a mechanistic explanation for the critical inflammasome-independent role of ASC in driving T cell and humoral responses during vaccination and in autoimmune diseases.

Results

ASC is required for antigen uptake and presentation

The presentation of antigenic peptides coupled to major histocompatibilty complex II (MHC II) receptors of professional phagocytes represents a critical step in the activation of adaptive immune responses that is dependent on actin polymerization43. The critical role of ASC in antigen presentation by MHC II receptors was confirmed by the observation that Asc−/− dendritic cells (DCs) were severely impaired in inducing proliferation of bovine serum albumin (BSA)-specific T ells (Fig. 1a). Moreover, wild-type T cells coincubated with Asc−/− DCs in the presence of BSA produced significantly less cytokines for TH1 (interferon- γ, IFN-γ) (Fig. 1b), TH2 (IL-6 and IL-10) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1), and TH17 (IL-17) (Fig. 1d) cytokines, further establishing the critical role of ASC in priming T cells. Unlike Asc−/− DCs, those lacking the inflammasome components Nlrp3 or caspase-1 elicited a T cell proliferative response that was comparable to that induced by wild-type DCs (data not shown), underlining the role of ASC in antigen presentation by dendritic cells independently of its role in inflammasome activation.

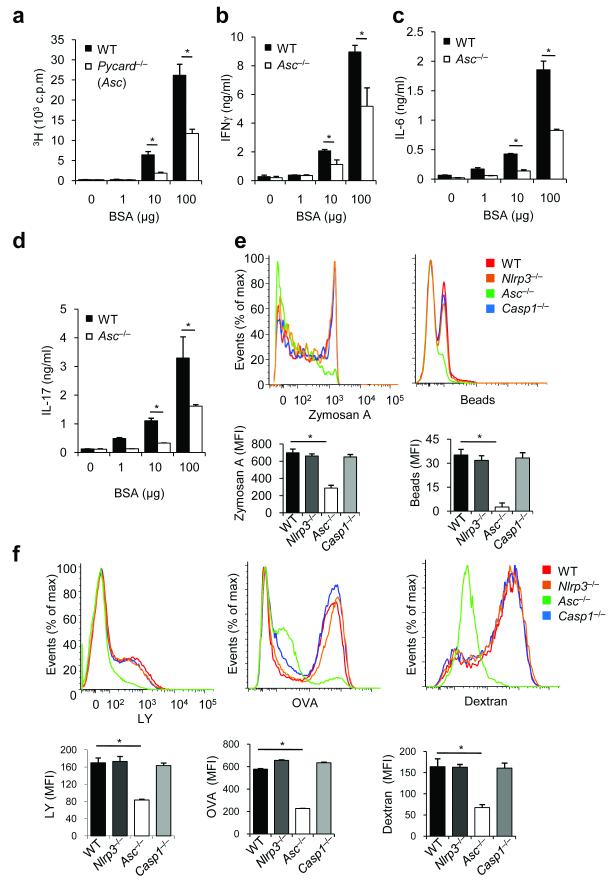

Figure 1. ASC controls antigen uptake and presentation independently of inflammasomes.

a-d, Dendritic cells from naïve wild-type (WT) and Asc−/− mice (n = 4–6 mice per group) were co-cultured with WT CD4+ T cells for 72 hours in the presence of the indicated concentrations of BSA. Dose-dependent antigen-specific proliferation of lymphocytes was assessed by measuring uptake of [3H]-thymidine (a), and by analyzing the levels of the cytokines IFNγ (b), IL-6 (c) and IL-17 (d). *P < 0.01 (two-tailed Student’s t-test). Data are a representative of three independent experiments (mean ± s.d in a–d) (e) WT, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and Casp1−/− bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were incubated for 3 h at 37° C with fluorescein-labeled zymosan A or polystyrene beads. Phagocytosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.0005. (f) WT, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and Casp1−/− BMDCs were incubated for 3 h at 37° C with fluorescein-labeled ovalbumin (OVA), dextran or luciferase yellow (LY). Macropinocytosis was anlayzed by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.005.

Antigen recognition and uptake by professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) represents one of the first steps in presenting peptides onto MHC class II receptors43. To explore the possibility that ASC is required for antigen uptake by professional phagocytes, wild-type, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were incubated with FITC-labeled zymosan A or polystyrene beads for 3 h and phagocytosis was measured by flow cytometry. Internalization of both zymosan A and polystyrene beads by Asc-deficient BMDCs was severely impaired, whereas phagocytosis by Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs was similar to wild-type cells (Fig. 1e). This result confirms that Asc−/− BMDCs are defective in phagocytosis of particulate antigens. To determine whether uptake of small soluble antigens, which proceeds through fluid endocytosis (macropinosis), was also affected by ASC deficiency, wild-type, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs were incubated with FITC-labeled dextran, FITC-labeled ovalbumin (OVA) or lucifer yellow (LY) for 3 h before cells were washed and macropinosis of these substances by cells of the respective genotypes was determined by flow cytometry. Dendritic cells lacking ASC were defective in internalizing dextran, OVA and LY (Fig. 1f). In contrast, macropinosis of dextran, OVA and LY by Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs was not affected. Together, these results indicate that ASC controls uptake and presentation of antigens in professional antigen-presenting cells independently of inflammasomes.

ASC is critical for lymphocyte chemotaxis and migration

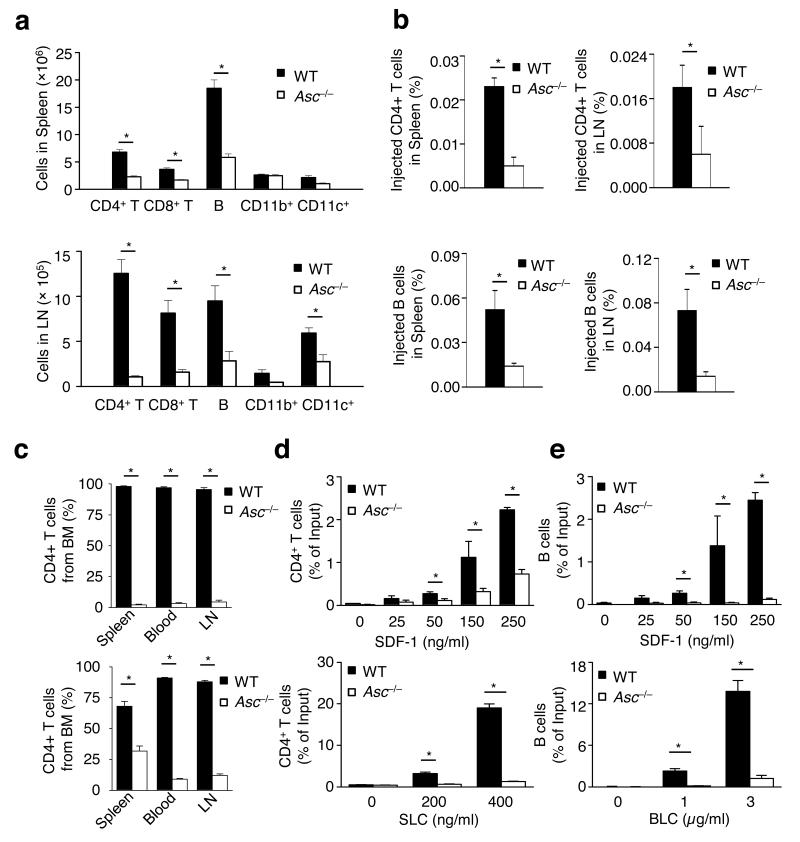

In addition to its role in regulating antigen uptake by professional phagocytes, ASC was proposed to exert cell-intrinsic functions in lymphocytes41, 42. In agreement, the total number of spleen and lymph node cells found in Asc−/− mice was about half of those in wild-type mice, with counts of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells and CD11c+ cells all being markedly reduced in Asc−/− spleens and lymph nodes (Fig. 2a). Nlrp3−/− and caspase1−/− mice had numbers comparable to those of wild-type mice in both the spleen and lymph nodes for each cell population (Supplementary Fig. 2). To determine whether ASC plays an important role during lymphocyte migration and T cell development, we analyzed the migration of congenically marked wild-type and Asc−/− lymphocytes to peripheral lymph nodes and spleens of wild-type mice. The intrinsic migratory capacity of Asc−/− T and B cells was severely impaired as illustrated by the significantly reduced numbers of both cell types retrieved in the spleen (Fig. 2b, left) and lymph nodes (Fig. 2b, right) of wild-type hosts. To confirm the intrinsic migratory defect of Asc−/− lymphocytes, we created mixed chimeras by injecting an equal ratio of wild-type and Asc−/− bone marrow into lethally irradiated wild-type mice. Six weeks after reconstitution, ~98% of the CD4+ T cells found in blood and secondary lymphoid organs were derived from wild-type bone marrow (Fig. 2c, top). Similarly, a large majority of circulating B cells were wild-type cells (Fig. 2c, bottom). In addition to intrinsic defects in migration, the markedly high ratio of WT/Asc−/− lymphocytes in mixed chimeras could also be due to differences in lymphocyte development and cell survival. Although leukocyte populations in Asc-deficient mice (Supplementary Fig. 3) and Asc chimeras (Supplementary Fig. 4) indeed contained slightly decreased numbers of single-positive thymocytes and modestly more double-negative T cells, these differences in thymocyte development were only minor. Nevertheless, to further confirm the migratory phenotype of Asc−/− T and B cells, we studied the in vitro migration of these cells towards chemokines. In agreement with a critical role for ASC in lymphocyte chemotaxis, splenic CD4+ T cells from Asc-deficient mice were nearly incapable of migrating towards the chemokines stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine (SLC) (Fig. 2d). Similarly, B cells from Asc−/− mice were severely defective in their migration towards both SDF-1 and lymphocyte chemokine (BLC) (Fig. 2e). In contrast, splenic T and B lymphocytes of Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− mice migrated towards these chemokines to a similar degree as wild-type lymphocytes (Supplementary Fig. S5). Thus, ASC is required for lymphocyte migration in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 2. ASC is required for lymphocyte migration in vitro and in vivo.

(a) Spleen and lymph node cells of WT and Asc−/− mice were collected and stained for CD4, CD8, CD19, CD11b and CD11c. Data are expressed as the percentage of the total lymphocyte population in the spleen (upper panel) and axillary lymph nodes (lower panel) belonging to each category in WT (filled bars) and Asc−/− mice (open bars). (b) Naïve WT mice were injected with an equal ratio of congenically marked CD4+ T cells or B cells from WT and Asc−/− mice. 48 h after later, the spleen and axillary lymph nodes were collected to determine the levels of congenically marked WT and Asc−/− CD4+ T and B cells that migrated into these tissues. Results are expressed as the percentage of injected cells detected in the spleen or lymph nodes. (c) Mice were lethally irradiated and injected with an equal ratio of congenically marked WT and Asc−/− bone marrow. Blood, spleen and axillary lymph nodes were analyzed 6 weeks later for congenically marked CD4+ T cells and B cells derived from WT or Asc−/− bone marrow. Results are expressed as the percentage of the total bone marrow-derived lymphocytes. (d), (e) Migration of splenocytes of wild-type (WT) and Asc−/− mice was analyzed in vitro using a transwell chemotaxis assay. Data are expressed as the percentage of the total CD4+ T lymphocyte (d) and B cell (e) population migrating across the transwell. *P < 0.005. (n = 3–4 mice per group). Results represent means ± S.E. of triplicates of three independent experiments (a–e).

ASC controls Rac activation and actin polymerization

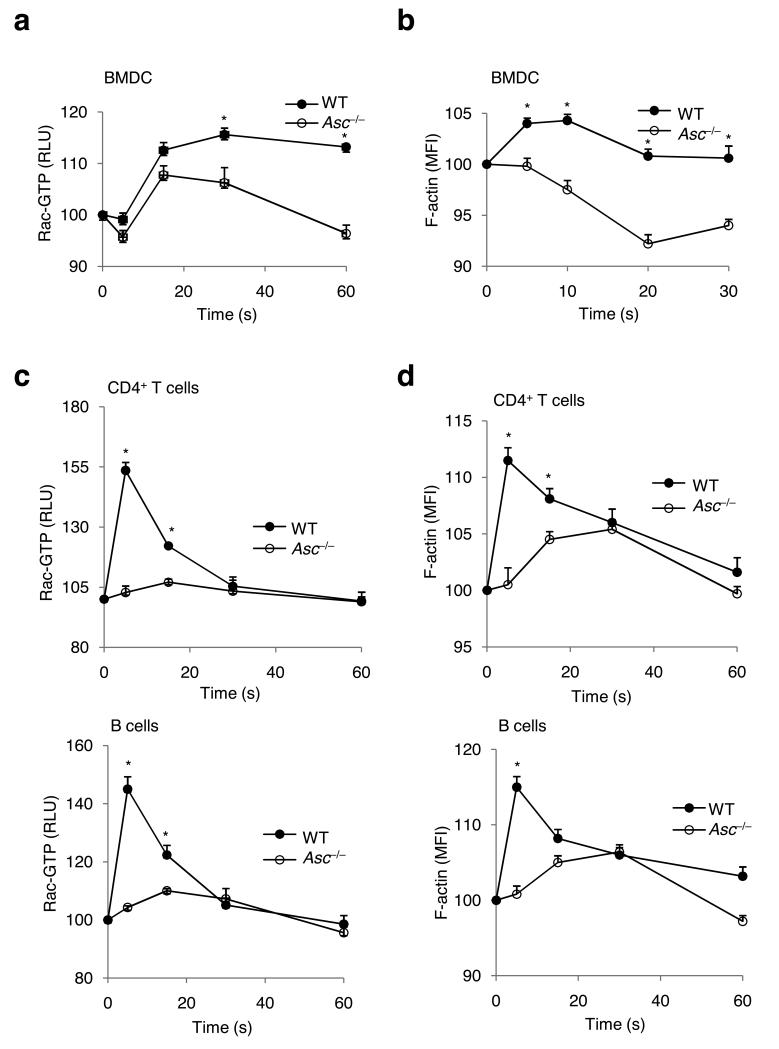

Both efficient endocytosis of antigens, and the migration of lymphocytes towards a chemokine gradient requires activation of small GTPases such as Cdc42 and Rac to induce F-actin polymerization and cytoskeletal reorganizations43. However, expression and activation of the Rho GTPase Cdc42 were not affected in ASC-deficient BMDCs and lymphocytes, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, ASC-deficient BMDCs were impaired in Rac activation (Fig. 3a) and F-actin polymerization (Fig. 3b) when incubated with OVA. Because lymphocyte migration relies on chemokine receptor-induced Rac activation and actin polymerization, we examined the extent of Rac activation following chemokine stimulation. While wild-type CD4+ T cells and B cells activated the GTPase Rac (Fig. 3c) and induced F-actin polymerization (Fig. 3d) when incubated with 500 ng/ml SDF-1, these responses were markedly reduced in Asc−/− T and B cells (Fig. 3c,d). The role of ASC in chemokine-induced Rac activation and F-actin polymerization in lymphocytes was specific because SDF-1-induced activation of the MAP kinase ERK was not affected in Asc−/− T and B lymphocytes (Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, defective antigen uptake by ASC-deficient dendritic cells and chemotaxis of Asc−/− lymphocytes is linked to impaired Rac activation and F-actin polymerization in these cells.

Figure 3. ASC is essential for antigen- and chemokine-induced Rac activation and actin polymerization in dendritic cells and lymphocytes, respectively.

(a), (b) wild-type (WT) and Asc−/− BMDCs were treated with OVA for the indicated durations before Rac GTPase activity (a) and actin polymerization (b) were determined by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. Baseline levels were arbitrarily assigned a value = 100. (c) CD4+ T cells and B cells isolated from spleens of WT and Asc−/− mice were treated in vitro with SDF-1 (500ng/mL) for the indicated durations before lysates were prepared and analyzed for Rac activation using a Rac1 G-LISA activation assay. (d) Isolated T and B cells from WT and Asc−/− mice were treated in vitro with SDF-1 (500ng/mL) for the indicated durations before actin polymerization was analyzed by flow cytometry. P-values <0.05 were considered significant (two-tailed Student’s t-test) (n = 1–3 per group) (a–d) Results represent means ± s.d. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments.

ASC regulates Dock2 expression independently of inflammasomes

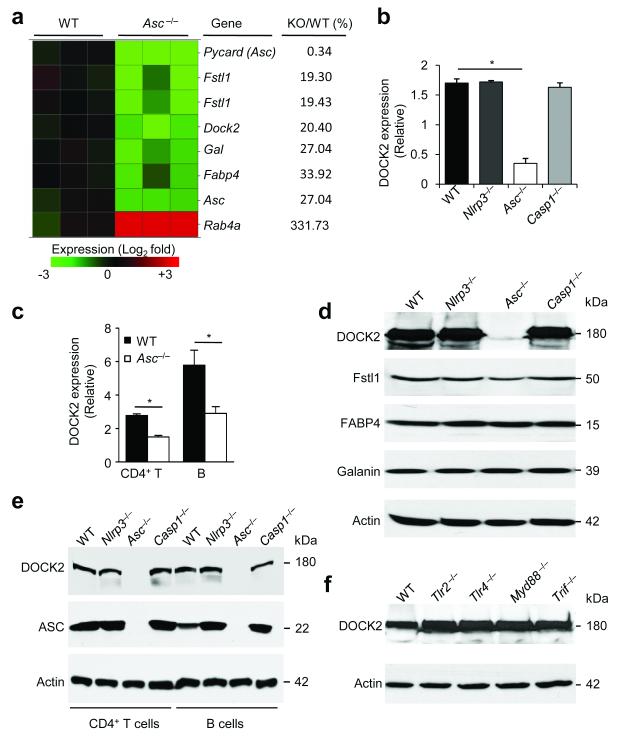

Our results showed that ASC regulates antigen uptake in dendritic cells and migration of lymphocytes independently of inflammasomes through modulation of Rac activation and F-actin polymerization. To characterize the molecular mechanism involved, we performed microarray experiments to identify genes that are dysregulated in ASC-deficient BMDCs, while being normally expressed in cells isolated from mice lacking the inflammasome proteins caspase-1 and Nlrp3. Notably, out of the over 39,000 transcripts represented on the microarray, the transcripts of only five genes were downregulated at least three-fold in ASC-deficient BMDCs relative to their expression in wild-type BMDCs (Fig. 4a). Apart from ASC, this included dedicator of cytokinesis 2 (Dock2; 5-fold), follistatin-like 1 (Fslt1; 5-fold), galanin (Gal, 3.7-fold) and fatty acid binding protein 4 (Fabp4, 3-fold). qPCR analysis confirmed the reduced mRNA expression of Dock2 in Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 4b), but the expression of Fslt1, Gal and Fabp4 were found to be unaltered in Asc−/− BMDCs when measured by qPCR (data not shown). Unlike in Asc−/− BMDCs, Dock2 mRNA abundance was normal in BMDCs from Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− mice (Fig. 4b), confirming that Dock2 transcript abundance is regulated by ASC in an inflammasome-independent manner. A similar decrease in Dock2 transcript abundance in the absence of ASC was observed in CD4+ T cells and isolated B cells (Fig. 4c). In contrast, Dock2 mRNA expression in Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− CD4+ T cells and B cells were comparable to those of wild-type cells (data not shown).

Figure 4. ASC regulates DOCK2 expression independently of inflammasomes and TLRs.

(a) RNA from naïve wild-type (WT) and Asc−/− BMDCs was analyzed for gene expression using a HT MG-430 PM array plate. All genes that of which the transcript levels in WT and Asc−/− BMDCs differed three-fold or more are listed. (b) The mRNA expression levels of Dock2 in naïve WT, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs were quantified by qPCR and normalized against GAPDH. (c) DOCK2 expression levels in purified CD4+ T cells and B cells from WT and Asc−/− mice were determined by qPCR and normalized against GAPDH. (d) Western blot analysis of DOCK2, Fstl1, Fabp4, Galanin and Actin expression in naïve WT, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs. (e) CD4+ T cells and B cells from WT, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− mice were purified and analyzed for protein expression of DOCK2 and ASC. (f) Lysates of naïve WT, Tlr2−/−, Tlr4−/−, MyD88−/− and Trif−/− BMDCs were analyzed for DOCK2 protein levels by Western blotting. Actin served as a loading control. Results are a representative of at least three independent experiments.

We next prepared lysates of wild-type, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs to analyze the protein expression of DOCK2, Fstl1, Gal and Fabp4 by immunoblotting. Interestingly, DOCK2 expression was nearly abolished in Asc−/− BMDCs, but not affected in Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs (Fig. 4d). Notably, the protein expression of Fstl1, Gal and Fabp4 were not affected in Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 4d), confirming the qPCR results. Additionally, Nlrp3 inflammasome activation by stimulation with LPS and ATP did not upregulate DOCK2 expression in Asc−/− BMDCs or macrophages (Supplementary Fig. 8). Moreover, DOCK2 expression remained stable in Nlrp3−/− and caspase-1−/− BMDCs treated with these stimuli (Supplementary Fig S8). ASC-dependent DOCK2 expression was confirmed in BMDMs and BMDCs from an independently generated line of Asc-deficient mice45 (Supplementary Fig. 9). The near complete absence of DOCK2 protein was also observed in Asc−/− T cells and B cells (Fig. 4e). These results indicate that ASC specifically regulates DOCK2 expression in an inflammasome-independent manner in myeloid cells and lymphocytes. We also explored whether ASC regulates DOCK2 expression in a Toll-like receptor (TLR)-dependent fashion, but DOCK2 expression was normal in BMDCs isolated from mice deficient for TLR2 or TLR4, as well as in cells lacking the common TLR adaptors MyD88 and TRIF (Fig. 4f). Thus, ASC specifically regulates DOCK2 expression in myeloid cells and lymphocytes in a TLR- and inflammasome-independent fashion.

ASC regulates Dock2 mRNA stability

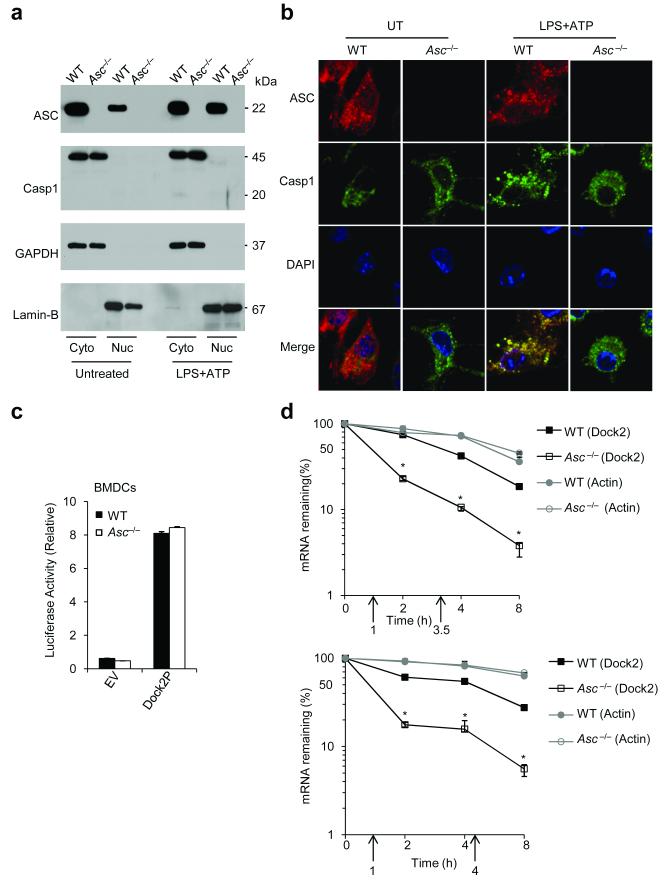

To characterize the mechanism by which ASC regulates Dock2 mRNA abundance, we first analyzed the subcellular localization of ASC in BMDCs by subcellular fractionation. Interestingly, ASC expression was detected in both the cytosol and the nucleus of naïve BMDCs (Fig. 5a). Notably, the subcellular localization of ASC to these compartments remained largely stable upon LPS+ATP-stimulation (Fig. 5a). As expected, the ASC antibody failed to detect immunoreactive bands in lysates of Asc−/− BMDCs, thus confirming its specificity. Unlike ASC, caspase-1 was exclusively located in the cytosol of naïve and LPS+ATP-stimulated BMDCs, suggesting that the nuclear pool of ASC is not recruited to inflammasome complexes (Fig. 5a). In agreement, analysis of confocal micrographs indicated that ASC and caspase-1 colocalized in the cytosol of LPS+ATP-stimulated, but not untreated, BMDCs (Fig. 5b). In contrast, ASC that is located in the nuclear compartment failed to colocalize with caspase-1 under these conditions (Fig. 5b), suggesting that nuclear ASC may be responsible for regulating Dock2 mRNA abundance in an inflammasome-independent manner.

Figure 5. ASC localizes to the nucleus and controls Dock2 mRNA stability.

(a) Wild-type (WT) and Asc−/− bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were left untreated or primed with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 h, of which the final 15 minutes in the presence of ATP (5 mM). The cytosolic (Cyto) and nuclear (Nuc) compartments were separated and normalized for protein concentrations. Lysates were probed for expression of ASC and caspase-1 by Western blotting. GAPDH and Lamin B served as compartment-specific markers for the cytosolic and nuclear compartments, respectively. (b) WT and Asc−/− BMDCs were left untreated or primed with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 4 h, of which the final 15 minutes in the presence of ATP (5 mM). Cells were subsequently washed in PBS, fixed, permeabilized and stained for ASC and caspase-1 as described in Materials and Methods. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. (c) WT and Asc−/− BMDCs were nucleofected with the pGL3 empty reporter vector (EV) or a pGL3 plasmid containing the Dock2 promoter (Dock2P). Luciferase activity was measured by scintillation counting. (d) WT and Asc−/− BMDCs were treated with 50μM DRB or 5μg/ml actinomycin-D before total RNA was prepared and expression levels of Dock2 and β-actin mRNA were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized against GAPDH. Baseline levels were arbitrarily assigned a value = 100. The t1/2 of mRNA stability was calculated as the time required for decay of 50% of baseline mRNA levels. *P < 0.005 (Student’s t-test) (d). Data presented represent means ± s.d. from one out of three (d) or four (e) independent experiments.

We next assessed whether nuclear ASC regulated transcriptional activity of the Dock2 promoter. To this end, the Dock2 promoter was cloned into the pGL3 reporter vector and used to analyze Dock2 promoter-driven luciferase production in wild-type and Asc−/− BMDCs. Luciferase expression was found to be similarly induced in wild-type and Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 5c), suggesting that ASC may regulate Dock2 mRNA abundance at the level of RNA stability instead. To analyze this possibility, Dock2 mRNA stability was examined in wild-type and Asc−/− BMDCs following treatment with 5,6-dichlororibofuranosyl benzimidazole (DRB) or actinomycin D to block de novo transcription. The half-life of Dock2 transcripts was markedly reduced from approximately 4 h in wild-type cells to around 30 min in Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 5d). Unlike Dock2, the half-life of β-actin was virtually unaffected in Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 5d), confirming the specificity of these results. Thus, regulation of Dock2 mRNA stability represents a major mechanism by which ASC controls DOCK2 expression. To examine a potential contribution of post-translational events to the regulation of DOCK2 protein expression, wild-type and Asc−/− cells were pretreated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 for 1, 4 or 6 h before lysates were probed for DOCK2 expression. Proteasome inhibition slightly increased DOCK2 expression in wild-type cells, but this was not sufficient to restore expression in Asc−/− cells (Supplementary Fig. 10).

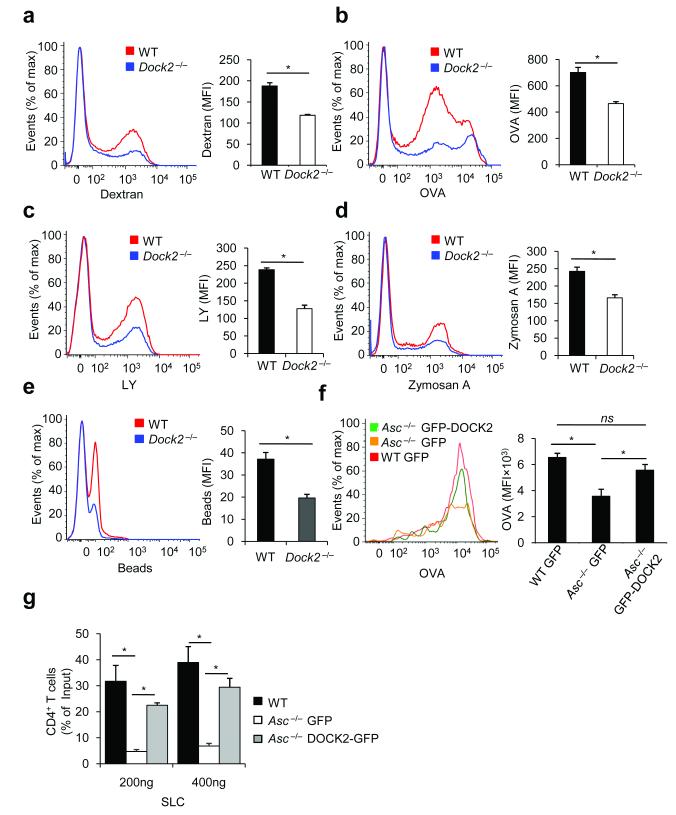

DOCK2 is critical for antigen uptake by dendritic cells

DOCK2 is an immune cell-specific member of a conserved family of guanine nucleotide exchange factors that has been identified as a central regulator of lymphocyte and plasmacytoid dendritic cell migration controlling Rac-dependent actin polymerization and cytoskeletal reorganizations in these cells44, 46, 47. However, its role in dendritic cell function has not been characterized. We hypothesized that similar to Asc−/− BMDCs (Fig. 1), professional phagocytes lacking DOCK2 may be impaired in antigen uptake and endocytosis. We first examined macropinosis of FITC-labeled dextran, FITC-ovalbumin (OVA) and Lucifer Yellow (LY) by wild-type and Dock2-deficient BMDCs. Uptake of dextran (Fig. 6a), OVA (Fig. 6b) and LY (Fig. 6c) by Dock2−/− BMDCs were all significantly impaired relative to the levels taken up by wild-type BMDCs, illustrating the important role of DOCK2 in endocytosis of soluble antigens by professional phagocytes. Uptake of larger particles and insoluble antigens proceeds through phagocytosis rather than macropinosis48. To determine the role of DOCK2 in phagocytosis, we compared the uptake of FITC-labeled zymosan A and FITC-labeled polystyrene beads by wild-type and Dock2−/− BMDCs. In agreement with an important role for DOCK2 in phagocytosis, Dock2-deficient dendritic cells were severely impaired in the internalization of zymosan A (Fig. 6d) and polystyrene beads (Fig. 6e) relative to wild-type controls. Importantly, ASC expression and inflammasome activation were normal in Dock2−/− BMDCs (Supplementary Fig. 11), further confirming that ASC- and DOCK2-mediated endocytosis is uncoupled from inflammasome signaling.

Figure 6. DOCK2 is critical for antigen uptake by dendritic cells, and restores immune cell functions in the absence of ASC.

(a–c) WT and Dock2−/− bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were incubated for 3 h at 37° C with FITC-labeled OVA (a), dextran (b) or LY (c). After incubation and washing, macropinocytosis was measured by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. (d–e) WT and Dock2−/− BMDCs were incubated for 3 h at 37° C with fluorescein-labeled zymosan A (d) or polystyrene beads (e). After incubation and washing, phagocytosis was analyzed by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. (f) WT and Asc−/− BMDCs were nucleofected with GFP- or GFP-DOCK2-expressing plasmids. Macropinocytosis of fluorescein-labeled ovalbumin (OVA) was determined 24h post-transfection by flow cytometry. Results represent mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. of triplicates of at least three independent experiments. (g) Migration of WT and Asc−/− CD4+ T lymphocytes expressing either GFP or GFP-DOCK2 was analyzed in vitro towards SLC in a transwell chemotaxis assay. Data represent means ± s.d. of triplicates of three independent experiments and are expressed as the percentage of the total T cell population migrating across the transwell.*P-values <0.05 were considered significant (a-g). Non-significant (ns).

Ectopic expression of DOCK2 restores ASC-mediated functions

The observation that DOCK2 is critical for internalization of soluble and insoluble antigens via both macropinosis and phagocytosis by professional APCs, together with our results showing that ASC controls DOCK2 expression in BMDCs and lymphocytes (Fig. 4,5) suggest that ASC may act upstream of DOCK2 in controlling DOCK2-dependent immune functions. Therefore, we tested whether the defective Rac activation, actin polymerization and antigen uptake by BMDCs and impaired lymphocyte migration observed in Asc−/− cells was due to the specific downregulation of Dock2 in these cells. To this end, Asc-deficient BMDCs were nucleofected with plasmids encoding eithergreen fluorescent protein (GFP) or a GFP-DOCK2 fusion protein. Endocytosis of OVA by GFP-DOCK2-expressing Asc−/− BMDCs was found to be significantly higher than uptake levels observed for Asc−/− BMDCs expressing GFP alone (Fig. 6f), thus confirming that DOCK2 is required downstream of ASC for antigen uptake by professional phagocytes. Similarly, ectopic expression of DOCK2 in Asc−/− T-cells restored their migration towards the chemokine SLC (Fig. 6g). Collectively, these data show that the functional defects observed in Asc−/− BMDCs and lymphocytes are due to a specific decrease in Dock2 mRNA stability that leads to impaired DOCK2 expression in the absence of ASC, and that ectopic expression of DOCK2 in the cells is sufficient to restore ASC-dependent immune cell functions.

Discussion

The adaptor protein ASC is well-known to contribute to innate immune responses by enabling activation of the cysteine protease caspase-1 in inflammasomes49,45. Recent studies provided evidence indicating that Asc−/− mice were protected against disease progression in animal models of arthritis and multiple sclerosis, where mice lacking the inflammasome components Nlrp3 or caspase-1 were not40-42. ASC was suggested to affect immune cell functions in either lymphocytes41, 42 or dendritic cells40. Although these observations suggested ASC to control immune cell functions through inflammasome-independent mechanisms, the molecular pathways have remained enigmatic. ASC was recently reported to regulate MAP kinase activation in macrophages by interacting with the protein DUSP10 in response to TLR ligands and infection with bacterial pathogens50. However, this function may be rather stimulus-dependent because earlier reports did not observe differential MAP kinase signaling in activated and infected Asc−/− macrophages45. Furthermore, we failed to detect changes in the expression of chemokine-induced ERK phosphorylation in Asc−/− immune cells.

Instead, we showed here that antigen presentation by dendritic cells and migration of T and B lymphocytes were markedly reduced in Asc−/− mice as a result of impaired Rac-mediated actin polymerization. Microarray and immunoblotting analysis of naïve and stimulated Asc−/− dendritic cells and lymphocytes revealed that ASC specifically regulates expression of DOCK2. The role of ASC in regulating Dock2 mRNA abundance is highly specific given that only 5 transcripts out of the 39,000 transcripts that were analyzed were found to be up- or down-regulated by at least 3-fold in Asc−/− BMDCs relative tothose found in wild-type BMDCs. Moreover, Dock2 was the only ASC-regulated gene of which expression was altered at the protein level as well. Rather than directly affecting Dock2 promoter activity, ASC played a critical role in stabilizing Dock2 mRNA because the half-life of Dock2 transcripts was markedly (8.0 fold) decreased in Asc−/− dendritic cells. Further analysis is required to determine the specific contribution of the nuclear and cytosolic pools of ASC to this process. Given that ASC lacks intrinsic enzymatic activity, ASC most likely affects DOCK2 abundance by assembling (one or more) protein complex(es) in the cytosol and/or nucleus that are distinct from the inflammasomes. Moreover, in addition to regulating the decay rate of Dock2 transcripts, ASC may contribute to yet unknown processes that regulate Dock2 mRNA and protein levels at the post-transcriptional and/or post-translational levels. These may include Dock2-targeting microRNAs, Dock2 mRNA splicing linked to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, Dock2 mRNA trafficking, DOCK2 translation rates and the levels of post-translational modifications that may influence DOCK2 trafficking and degradation in lysosomes. However, the marked effect of ASC-deficiency on Dock2 mRNA decay rates may hamper a detailed analysis of the potential role of ASC in regulating DOCK2 expression through these additional mechanisms. Regardless, downregulated DOCK2 expression was confirmed as the mechanism driving defective phagocytosis and antigen presentation by dendritic cells and dysfunctional chemotaxis of lymphocytes in the absence of ASC. For example, ectopic expression of DOCK2 in ASC-deficient cells rescued lymphocyte migration and antigen uptake by dendritic cell. Thus, the observation that ASC controls DOCK2 expression and DOCK2-mediated regulation of Rac activation and actin polymerization provides a molecular basis for the defective antigen presentation by dendritic cells and the lymphocyte-intrinsic defects in cell migration observed in the studies cited above.

In conclusion, we provided genetic evidence for a critical and unexpected role for ASC in regulating T and B lymphocyte motility and antigen uptake by professional antigen-presenting cells independently of inflammasomes. Instead, ASC controls Dock2 transcript stability and expression of DOCK2, a protein critical for Rac activation and actin polymerization during lymphocyte migration and antigen uptake. These observations reveal a new role for ASC in regulating adaptive immune responses that is intrinsic to lymphocytes and dendritic cells. The vital role of ASC in regulating both adaptive and innate immune responses suggests that modulating ASC expression and functions may represent a powerful therapeutic strategy for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Flavell (Yale University School of Medicine), G. Nunez (University of Michigan) and S. Akira (Osaka University) for the generous supply of mutant mice and H. Chi for retroviral plasmids. This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants (R01AR056296, the supplements and R21AI088177), a NIAMS Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) grant and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) to T-D.K., and by European Union Framework Program 7 Marie-Curie grant 256432 to M.L. M.L. and L.V.W. are supported by the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders.

Abbreviations

- DOCK2

dedicator of cyto-kinesis 2

- WT

wild-type

- Casp1

caspase-1

- DC

dendritic cell

- NLR

NOD-like receptor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

APPENDIX

Methods

Mice

Both independent Asc−/− mouse lines used in this study have been characterized before45, 51. Nlrp3−/−, caspase-1−/−, Tlr2−/−, Tlr4−/−, MyD88−/−, Trif−/− and Dock2−/− mice were described previously2, 44. All mice have been backcrossed at least ten generations into theC57BL/6J genetic background. Mice were housed in a pathogen-free facility and the animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Committee on Use and Care of Animals or by the Ghent University Hospital ethical committee.

Microarray analysis and qPCR

Isolated RNA quality was confirmed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer prior to microarray analysis. RNA samples were processed on a HT MG-430 PM array plate using the Affymetrix GeneTitan System. Three biological replicates of naive WT and Asc−/− BMDCs were analyzed by microarray and transcript expression values were summarized using the RMA method52. Differential expression between WT and Asc−/− BMDC samples was analyzed using an Empirical Bayesian method (CyberT, http://cybert.ics.uci.edu)53, and the false discovery rate (FDR) was estimated as described54. For DOCK2 qPCR, samples were analyzed using specific primers (forward–5′-TTGCTCAGCCAGCTACTGTATG-3′; reverse–5′-TTGGTGATGACAGGAAGCAGAAT-3′). Quantification was normalized relative to the reference gene Gapdh.

Subcellular fractionation

Cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction extractions were performed using NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblot analysis

Standardized protein concentrations of cellular lysates were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Antibodies against DOCK2 (09-454), ASC (Enzo Life Sciences, AL177), caspase-1 (kind gift of P. Vandenabeele, Ghent University), Fstl1 (R&D, AF1738), FABP4 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2120), Galanin (Abcam, ab99452) and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, 4970) were used at a final dilution of 1:1000. Detection was done using HRP-based enhanced chemiluminescence (thermoscientific, 34095).

Transfection

Immature BMDCs were transfected using a Nucleofector kit (Lonza, VPA-1009) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h prior to performing antigen uptake assays.

Retroviral transduction

GFP-Dock2 and GFP were cloned in to MSCV retroviral vector. Phoenix-Eco packaging cells were transfected with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, 11668-027) and the recombinant viruses were collected 48 h and 72 h after transfection. Total spleen cells were isolated and cultured for 24 h with 2.5 μg/ml of anti-CD3, 5 μg/ml of anti-CD28 and 100 U/ml of IL-2 and then transduced with retroviruses by ‘spin inoculation’. GFP positive cells were flow sorted and then used for chemotaxis assays.

T cell proliferation

Popliteal lymph nodes were collected after 10 days of immunization with 10 μg of BSA (Sigma, 85040) in CFA emulsion. CD4+ T cells were isolated by negative selection using a mouse CD4+ T cell enrichment strategy (Milteny AutoMACS, 130-095-248). CD4+CD11c+ dendritic cells (130-091-262) were isolated from Collagenase-D (Roche, 11088874103) treated spleens of naïve Asc+/+ and Asc−/− mice according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Co-cultures were set with 5 × 105 of CD4+ T cells/well and 2.5 × 105 of the indicated type of dendritic cells/well, and the indicated concentration of antigen. Cultures were maintained in U-bottom plates in 300 μl of HL-1 medium (Lonza, 7720) supplemented with 50 U/ml Penicillin G and 50 μg/ml Streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 292 μg/ml L-Glutamine and 0.1 % BSA, at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 72 h. Supernatants were harvested for evaluation of cytokine production and cultures were pulsed with 3H-thymidine (1 μCi/well in 10μl), incubated for an additional 18 h, harvested onto Unifilter GF/C plates and counted (Counts/minute (CPM) on a TopCount NXT (PerkinElmer).

Cytokine Measurements

Cytokine levels were determined using Milliplex ELISA kit (Millipore).

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was carried out by staining the cells with the antibodies CD4 (L3T4), CD8 (53-6.7), CD11b (M1/70), B220 (RA3-6B2) from eBioscience, CD8a(53-6.7), TCR-β (H57-597), CD44 (IM7), CD69(H1.2F3), CD11c (N418), CD45.1 (A20), and CD45.2 (104) from Biolegend and analyzed on a LSR II (Becton-Dickinson). To assess antigen uptake and phagocytosis, dendritic cells were incubated with ovalbumin, dextran, luciferase yellow, zymosan A or beads conjugated with fluorochromes for 3 h. Cells were washed several times and analyzed by flow cytometry. To assess actin polymerization, isolated T and B cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with permwash (Biolegend, 421002) and stained with Alexa 488-labeled phalloidin (BD Biosciences) for flow cytometry.

Confocal microscopy

100,000 BMDCs were plated on glass cover slips (BD Biosciences), and 24 h later, cells were stimulated, washed in PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Blocking was done with blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 60 min. Cells were co-stained for 1 h with 1 μg/ml of mouse monoclonal ASC Ab (Millipore, 04-147) and rabbit polyclonal caspase-1 (ref.51) (kind gift of P. Vandenabeele, Ghent University) in blocking buffer. After washing, bound Ab were detected with goat anti-rabbit Alexa fluor-488 (Green, Casp1) and chicken anti-mouse Alexa fluor-647 (Red, ASC) for 1 h at °25C. Slides were mounted with Prolong gold-DAPI Mounting Media (Invitrogen, P-36931) and analyzed with Inverted Spinning Disk Confocal Microscope (Zeiss) with a 63X objective lens using the Slidebook software. Specificity of ASC and Caspase-1 antibodies were confirmed using their respective knock out BMDC cells as negative controls. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

Luciferase (Promoter activity) assay

The Dock2 promoter (−4000 to +100 bp) was amplified from mouse genomic DNA (forward–5′-GATCGTCGACGCAAGGTCAGAAATTTTGTTAGAAAAGATTTTAAA-3′; reverse–5′-CATGGGATCCCCCACACTTGCCCACACCTAC-3′) and cloned in to the pGL3-Enhancer vector upstream to the fire fly luciferase reporter gene. BMDCs were cotransfected with combinations of pGL3-Dock2 promoter reporter plasmid or pGL3 enhancer empty vector, control TK-Renilla luciferase, using Amaxa dendritic cell nucleofector kit (Lonza). Luciferase activity was then quantitated 24h post-trasfection by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The Dock2 promoter (firefly luciferase) activity was normalized to an internal control (Renilla luciferase). The experiments were carried out in triplicates and were repeated at least three times.

Competitive reconstitution mixed chimeras

WT CD45.1 congenic mice were lethally irradiated with a split dose of 1200 Rads. Bone marrow from CD45.1/2 WT and CD45.2 Asc−/− mice was injected intravenously at a 1:1 ratio. After 6 weeks of reconstitution, the percentages of WT vs. Asc−/− CD4+ T cells and B cells were calculated using CD45.1 and CD45.2 antibodies (Biolegend, A20 and 104).

Chemotaxis assay

Splenocytes (1.5 × 106) in 100 μL RPMI medium were placed in transwells (5 μm pore size), which were placed onto 24-well plates containing 500 μL RPMI supplemented with chemokines (R&D Systems) at various concentrations. Cells were incubated for 3 h at 37° C. Cells placed in the transwell and those which migrated to the lower chamber were collected and stained with the antibodies, TCR-β (H57-597), B220 (RA3-6B2) from eBioscience

GTPase activity assays

mRNA stability assay

De novo transcription was inhibited by culturing BMDCs in the presence of 50 μM 5,6-dichloro-1-β-ribofuranosyl benzamidazole (DRB; Sigma-Aldrich, D191) o r 5 μg/ml actinomycin-D (Sigma-Aldrich, A1410) for the indicated durations. Total RNA was subsequently isolated to measure DOCK2 and β-actin transcript abundance by real-time RT-qPCR. Transcript abundance was normalized against GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated with Student’s t-test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Footnotes

Accession codes.

GEO: microarray data, GSE30769

Author contributions

T-DK, ML, SKI, PJS, RKSM designed research; SKI, PJS, RKSM, GAN, LVW performed research; YF provided reagents; T-DK, ML, SKI, PJS, RKSM, GAN, YF analyzed data; PJS, ML and T-DK wrote the paper.

Competing interests statement

The authors declared no competing interests.

References Cited

- 1.Villani AC, et al. Common variants in the NLRP3 region contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nature Genet. 2009;41:71–76. doi: 10.1038/ng285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaki MH, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity. 2010;32:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen IC, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome functions as a negative regulator of tumorigenesis during colitis-associated cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1045–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer C, et al. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut. 2010;59:1192–1199. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupaul-Chicoine J, et al. Control of intestinal homeostasis, colitis, and colitis-associated colorectal cancer by the inflammatory caspases. Immunity. 2010;32:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin Y, et al. NALP1 in vitiligo-associated multiple autoimmune disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1216–1225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magitta NF, et al. A coding polymorphism in NALP1 confers risk for autoimmune Addison’s disease and type 1 diabetes. Genes Immun. 2009;10:120–124. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen CM, et al. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agostini L, et al. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nature Genet. 2001;29:301–305. doi: 10.1038/ng756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamkanfi M. Emerging inflammasome effector mechanisms. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:213–220. doi: 10.1038/nri2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. The inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000510. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: guardians of cytosolic sanctity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amer A, et al. Regulation of Legionella phagosome maturation and infection through flagellin and host Ipaf. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35217–35223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franchi L, et al. Cytosolic flagellin requires Ipaf for activation of caspase-1 and interleukin 1beta in salmonella-infected macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ni1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariathasan S, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao EA, et al. Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1beta via Ipaf. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:569–575. doi: 10.1038/ni1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki T, et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutterwala FS, et al. Immune recognition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated by the IPAF/NLRC4 inflammasome. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3235–3245. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miao EA, Ernst RK, Dors M, Mao DP, Aderem A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa activates caspase 1 through Ipaf. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2562–2567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712183105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franchi L, et al. Critical role for Ipaf in Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced caspase-1 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:3030–3039. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyden ED, Dietrich WF. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet. 2006;38:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanneganti TD, et al. Critical role for Cryopyrin/Nalp3 in activation of caspase-1 in response to viral infection and double-stranded RNA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36560–36568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutterwala FS, et al. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanneganti TD, et al. Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunity. 2007;26:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muruve DA, et al. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broz P, et al. Redundant roles for inflammasome receptors NLRP3 and NLRC4 in host defense against Salmonella. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1745–1755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu J, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Involvement of the AIM2, NLRC4, and NLRP3 inflammasomes in caspase-1 activation by Listeria monocytogenes. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:693–702. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9425-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren SE, et al. Cutting edge: Cytosolic bacterial DNA activates the inflammasome via Aim2. J. Immunol. 2010;185:818–821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuchiya K, et al. Involvement of absent in melanoma 2 in inflammasome activation in macrophages infected with Listeria monocytogenes. J. Immunol. 2010;185:1186–1195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauer JD, et al. Listeria monocytogenes triggers AIM2-mediated pyroptosis upon infrequent bacteriolysis in the macrophage cytosol. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rathinam VA, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandes-Alnemri T, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miao EA, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nature Immunol. 2010;11:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Nunez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasula SM, et al. The PYRIN-CARD protein ASC is an activating adaptor for caspase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21119–21122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellebedy AH, et al. Inflammasome-independent role of the apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing CARD (ASC) in the adjuvant effect of MF59. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2927–2932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012455108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McElvania Tekippe E, et al. Granuloma formation and host defense in chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection requires PYCARD/ASC but not NLRP3 or caspase-1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ippagunta SK, et al. Inflammasome-independent role of apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) in T cell priming is critical for collagen-induced arthritis. J Biol Chem. 285:12454–12462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolly L, et al. Inflammatory role of ASC in antigen-induced arthritis is independent of caspase-1, NALP-3, and IPAF. J Immunol. 2009;183:4003–4012. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw PJ, et al. Cutting edge: critical role for PYCARD/ASC in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2010;184:4610–4614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trombetta ES, Mellman I. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:975–1028. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukui Y, et al. Haematopoietic cell-specific CDM family protein DOCK2 is essential for lymphocyte migration. Nature. 2001;412:826–831. doi: 10.1038/35090591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mariathasan S, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanui T, et al. DOCK2 regulates Rac activation and cytoskeletal reorganization through interaction with ELMO1. Blood. 2003;102:2948–2950. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gotoh K, et al. Differential requirement for DOCK2 in migration of plasmacytoid dendritic cells versus myeloid dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;111:2973–2976. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanneganti TD. Central roles of NLRs and inflammasomes in viral infection. Nature Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:688–698. doi: 10.1038/nri2851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taxman DJ, et al. The NLR adaptor ASC/PYCARD regulates DUSP10, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and chemokine induction independent of the inflammasome. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19605–19616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanneganti TD, et al. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature. 2006;440:233–236. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldi P, Long AD. A Bayesian framework for the analysis of microarray expression data: regularized t -test and statistical inferences of gene changes. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:509–519. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J.R.Stat.Soc.B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.