Abstract

BMP4 loss-of-function mutations and deletions have been shown to be associated with ocular, digital, and brain anomalies, but due to the paucity of these reports, the full phenotypic spectrum of human BMP4 mutations is not clear. We screened 133 patients with a variety of ocular disorders for BMP4 coding region mutations or genomic deletions. BMP4 deletions were detected in two patients: a patient affected with SHORT syndrome and a patient with anterior segment anomalies along with craniofacial dysmorphism and cognitive impairment. In addition to this, three intragenic BMP4 mutations were identified. A patient with anophthalmia, microphthalmia with sclerocornea, right-sided diaphragmatic hernia, and hydrocephalus was found to have a c.592C>T (p.R198X) nonsense mutation in BMP4. A frameshift mutation, c.171dupC (p.E58RfsX17), was identified in two half-siblings with anophthalmia/microphthalmia, discordant developmental delay/postaxial polydactyly, and poor growth as well as their unaffected mother; one affected sibling carried an additional BMP4 mutation in the second allele, c.362A>G (p.H121R). This is the first report indicating a role for BMP4 in SHORT syndrome, Axenfeld–Rieger malformation, growth delay, macrocephaly, and diaphragmatic hernia. These results significantly expand the number of reported loss-of-function mutations, further support the critical role of BMP4 in ocular development, and provide additional evidence of variable expression/non-penetrance of BMP4 mutations.

Introduction

Bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) is a member of a large cytokine family related to the transforming growth factor-beta proteins. Bmp4 is an important regulator of normal development causing numerous embryonic defects when mutated or misexpressed in vertebrates (Chang et al. 2001; Furuta and Hogan 1998; Hogan 1996; Jiao et al. 2003; Solnica-Krezel 1999).

In humans, disruption of BMP4 by deletion or mutation was shown to be associated with ocular, digital, and brain anomalies. BMP4 is located at chromosome 14q22–q23, near the OTX2 gene, which is a well-established cause of anophthalmia/microphthalmia (Ragge et al. 2005; Schilter et al. 2010). Deletion of BMP4 was first demonstrated in combination with OTX2 deletion in three patients with anophthalmia, pituitary defects, developmental delay, and structural brain anomalies with syndactyly, brachydactyly, and genitourinary anomalies in one (Bakrania et al. 2008; Nolen et al. 2006). A patient with de novo deletion of BMP4 but not OTX2 was subsequently reported with congenital glaucoma and sclerocornea, postaxial polysyndactyly, brain anomalies, and developmental delay (Hayashi et al. 2008). Two families with anophthalmia/microphthalmia and intragenic mutations in BMP4 have been identified (Bakrania et al. 2008). The first mutation, c.226delAG (p.S76CfsX29), was identified in a proband with unilateral anophthalmia and coloboma, retinal dystrophy, and small anterior segment of the contralateral eye, along with postaxial polydactyly, structural brain anomalies, and learning difficulties. The c.226delAG mutation was seen in three additional family members affected with high myopia and/or polydactyly. The second, c.278A>G (p.E93G), was identified in a proband with bilateral microphthalmia, broad hands with low-placed thumbs, brain anomalies, and developmental delay. The p.E93G mutation was inherited from the father, whose only anomaly was mild inferior pigmentation of both retinas. A third variant in BMP4, c.751C>T (p.H251Y), was detected in a proband with mild microphthalmia (corneal diameter 10.7 mm; axial length 20.2 mm) and anterior segment anomalies as well as his unaffected brother (Zhang et al. 2009). The role of BMP4 in anterior segment development/glaucoma is further supported by animal studies demonstrating anterior segment dysgenesis and elevated intraocular pressure in Bmp4 +/− mice and defects in BMP4 signaling in experimental glaucoma models (Chang et al. 2001; Wordinger et al. 2007).

In addition to ocular phenotypes, BMP4 was shown to be associated with cleft lip and palate (Suzuki et al. 2009), renal malformations (Weber et al. 2008), and colorectal cancer (Lubbe et al. 2011). Heterozygous missense mutations in BMP4 were identified in seven probands with subepithelial, microform, and overt cleft lip/palate, and a nonsense mutation, p.R198X, was identified in another proband with overt cleft lip and palate; no information was provided regarding presence or absence of additional anomalies in these patients. All of the missense mutations were inherited from either mildly affected (three cases) or unaffected parents (four cases); inheritance of the nonsense mutation was not examined (Suzuki et al. 2009). Heterozygous missense mutations in BMP4 were also identified in four probands with renal agenesis, dysplasia, or hypoplasia, and a homozygous missense mutation was seen in one proband with cystic dysplasia of the kidneys; again, no details were provided regarding presence or absence of additional anomalies. Three of the mutations were inherited from unaffected parents (including both parents of the homozygous case): one was de novo, and the parents were not tested in the remaining two cases (Weber et al. 2008). Finally, BMP4 coding region variants were identified in six probands with colorectal cancer in a case/control mutation screen (Lubbe et al. 2011). Based on in silico analysis and control data, the authors classified two missense and one nonsense (p.R286X) variants as pathogenic mutations; no inheritance pattern analysis was performed, and no additional systemic anomalies were documented for any of these cases (Lubbe et al. 2011).

We present results from screening of BMP4 in patients with various ocular conditions. Five new deletions/mutations in BMP4 were found in four families. Our screening identified two deletions of BMP4 but not OTX2, including one in a patient with SHORT syndrome, one nonsense mutation, and one frameshift mutation which was detected in two half-siblings with discordant phenotypes with an additional missense mutation in one.

Materials and methods

This human study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, the University of Michigan, and Albert Einstein Healthcare Network with written informed consent obtained from every subject. Genomic DNA was extracted using standard procedures from blood or buccal samples. Complete sequence of the BMP4 coding region (reference sequence NM_001202.3) was obtained for 133 patients including 60 with anophthalmia/microphthalmia (34 syndromic), 38 anterior segment disorders (29 syndromic) including 3 with SHORT syndrome, 16 cataracts, 4 coloboma, 5 high myopia, and 10 other disorders using the following primers: set 1 forward, cttgatctttctgacctgct, and reverse, ttcttggaggtaagcagctc, PCR product equal 656 bp and set 2 forward, attgcccaaccctgagctat, and reverse, ccagctataaggaagcagtc, PCR product equal 1,069 bp. Patients with a genetic etiology identified in previously reported and unreported screens were excluded. Sequences were reviewed manually and using Mutation Surveyor (SoftGenetics, State College, PA, USA). All mutations were confirmed by independent sequencing reactions using new PCR products. Screening for deletions of BMP4 was performed using Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 or TaqMan assays in 89 of the above patients, including 40 patients with anophthalmia/microphthalmia and 26 with anterior segment disorders. In addition, all deletions were confirmed using TaqMan assays [BMP4 probes Hs02617539_cn (5′) and Hs00282899_cn (3′) that recognize sequences located within the BMP4 first and last exons, respectively, and OTX2 probe Hs01323383_cn designed against OTX2 exon 3 (first coding exon) sequence]. In order to determine the orientation of the BMP4 mutations identified in Patient 5, PCR product obtained with set 1 primers and the patient’s DNA was cloned into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) followed by DNA sequencing of nine independent clones corresponding to single BMP4 alleles.

A total of 179 Caucasian, 89 African American, 91 Asian, and 93 Hispanic controls described previously (Reis et al. 2010) were screened for mutations in BMP4.

Results

A deletion of BMP4 was detected in two unrelated patients (Patients 1 and 2), a nonsense mutation was detected in a third patient (Patient 3), and a frameshift mutation was detected in a pair of affected half-siblings (Patients 4 and 5) with an additional missense mutation in one (Patient 5). The previously reported c.455T>C (p.V152A) polymorphism was also seen in cases and controls.

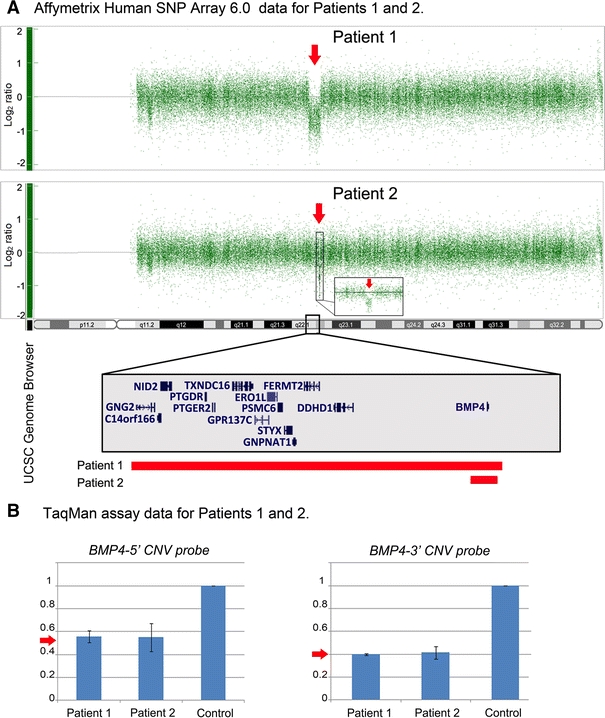

Patient 1 (Fig. 1a–c; Table 1) is a 6-year-old Caucasian female with a diagnosis of SHORT syndrome. Her ocular features include Rieger anomaly, congenital glaucoma, microcornea, and nystagmus. She has short stature, poor weight gain, and macrocephaly with measurements of 106.4 cm (3rd centile), 14.9 kg (<3rd centile), and 55 cm (>95th centile), respectively. The patient also has hyperextensible joints, delayed eruption of teeth (first teeth appeared at nearly 2 years of age), decreased subcutaneous fat in upper trunk and head, and dysmorphic facial features including prominent forehead, sunken eyes, small chin, and hypoplastic nares. Hearing is normal; hands and feet appear small with normal structure. Umbilicus is described as ‘a bit pouchy’ with mildly increased skin. She has a history of mildly delayed motor milestones felt to be related to her joint hypermobility; she currently receives special education services related to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and vision problems. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed normal structures. Peripheral blood chromosomes showed 46,XX (580 bands); previous screening of PITX2 showed normal sequence and copy number (data not shown). The patient was found to have a 2,263-kb deletion (1,508 probes in haploid state; minimum interval chr14: 51,402,258–53,665,008; maximum interval chr14: 51,400,039–53,667,259; based on UCSC 2006 hg18 assembly) of 14q22.1–14q22.2 which deletes one copy of BMP4 as well as GNG2, NID2, C14orf166, PTGDR, PTGER2, TXNDC16, GPR137C, ERO1L, PSMC6, STYX, GCPNAT1, PLEKHC1, and DDHD1 (Fig. 2a). BMP4 is the most distal gene included in the deletion, but the deletion extends past the end of the coding region of BMP4. Quantitative PCR data obtained with TaqMan probes confirmed deletion of one copy of BMP4 (Fig. 2b) and presence of both copies of OTX2 (data not shown). The mother (noted to have high myopia but otherwise normal ocular and other systemic features) was tested by TaqMan assay and showed no evidence of BMP4 deletion; the unaffected father is not available for testing.

Fig. 1.

Patient 1 with SHORT syndrome demonstrating short stature, macrocephaly, decreased subcutaneous fat in upper trunk and head, prominent forehead, sunken eyes, small chin, and hypoplastic nares (a) along with Rieger anomaly, congenital glaucoma, and microcornea (b, c). Patient 2 with bilateral microphthalmia, maxillary hypoplasia with midface flattening, thin upper lip, broad nasal bridge and tip, and telecanthus (d). Patient 3 with right anophthalmia/severe microphthalmia, left mild microphthalmia with sclerocornea, facial asymmetry macrocephaly (e). Patient 4 with bilateral clinical anophthalmia (f) and Patient 5 with left anophthalmia (prosthesis in place) (g)

Table 1.

Summary of BMP4 loss-of-function mutations and patient features

| BMP4 mutationa | Eye | Digit | Brain/neuro | Craniofacial | Growth | Other | Family history | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deletionsb | ||||||||

| Patient 1, this study | 2,263-kb deletion (+ 13 genes) | Rieger anomaly, congenital glaucoma microcornea, nystagmus | Hands/feet appear small | Mild gross motor delay with hypotonia; normal brain structures | Macrocephaly, prominent forehead, sunken eyes, small chin, hypoplastic nares | Height and weight ≤3rd centile | SHORT syndrome; hyperextensible joints, teething delay, lipodystrophy, umbilical anomaly | Parents unaffected; mother does not carry deletion; father not tested |

| Patient 2, this study | 158-kb deletion (BMP4 only) | Microphthalmia, persistence of pupillary membrane, high myopia, strabismus, nystagmus, corectopia (right) | WNL | Mild–moderate cognitive impairment, hypotonia; no imaging studies | Maxillary hypoplasia, midface flattening, thin upper lip, broad nasal bridge and tip, telecanthus, preauricular ear tag | WNL | None | Not available |

| Hayashi et al. (2008) | 2,700-kb deletion (+ 17 genes) | Congenital glaucoma, sclerocornea | Bilateral postaxial polydactyly (feet) | Global delay; Decreased brain white matter, lateral ventricular dilatation | Micrognathia | Weight <3rd centile | None | De novo deletion |

| Intragenic mutations | ||||||||

| Patient 3, this study | c.592C>T (p.R198X) | Anophthalmia; microphthalmia with sclerocornea | WNL | Development normal; hydrocephalus, diffuse cerebral atrophy | Facial asymmetry, macrocephaly, large anterior fontanelle | Height >97th centile | Right sided diaphragmatic hernia, laryngomalacia, inguinal hernia | De novo mutation |

| Patient 4, this study | c.171dupC (p.E58RX17) | Anophthalmia | WNL | Development normal; Normal brain structures | Small ears | Height <3rd centile | Small renal cyst (left) | Affected half-sister (Patient 5) and unaffected mother carry the mutation |

| Patient 5, this study | c.171dupC (p.E58RX17); c.362A>G (p.H121R) in trans | Anophthalmia (left), blepharophimosis | Bilateral postaxial polydactyly (hands) | Development normal; normal brain structures | Telecanthus, relative macrocephaly (75th centile), frontal bossing | Height and weight <3rd centile | None | Above; Father not available |

| Bakrania et al. (2008) | c.226delAG (p.S76CfsX29) | Anophthalmia; Microanterior segment, iris and chorioretinal coloboma, retinal dystrophy | Bilateral postaxial polydactyly (feet) | Learning difficulties; hypoplastic corpus callosum, enlarged trigones, sulcal widening | WNL | Not reported | None | Mutation seen in mother, grandmother, and great aunt with polydactyly and/or high myopia |

| Suzuki et al. (2009) | c.592C>T (p.R198X) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Cleft lip and palate | Not reported | Not reported | Parents not tested |

| Lubbe et al. (2011) | c.856C>T (p.R286X) | None | None | None | None | Not reported | Colorectal cancer diagnosed at 42 years | Parents not tested; no first degree relative with colorectal cancer |

aNucleotide numbering is relative to reference sequence NM_001202.3 where +1 is the A of the ATG initiation codon

bPatients with deletion of OTX2 in addition to BMP4 were excluded as OTX2 is a well-established cause of ocular and pituitary defects; therefore, the contribution of BMP4 to the phenotype could not be determined

Fig. 2.

Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 microarray analysis (a) and TaqMan assay data (b) for Patients 1 and 2. Heterozygous BMP4 deletions (arrows in a and b) were detected. The UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu) view of the deleted region indicating positions of genes is shown with rectangular bars indicating the extent of the deletion in each patient

Patient 2 (Fig. 1d; Table 1) is a 12-year-old Caucasian female with right corectopia, bilateral microphthalmia, bilateral persistence of the pupillary membrane, high myopia, strabismus, and nystagmus. The patient also has a history of hypotonia and mild–moderate cognitive impairment. The patient has dysmorphic facial features including maxillary hypoplasia with midface flattening, thin upper lip, broad nasal bridge and tip, telecanthus, and had a preauricular ear tag on the right. She has normal growth, head circumference, umbilicus, hands, and feet. Head imaging studies are not available. Peripheral blood chromosome analysis showed 46, XX (550 bands), and subtelomeric FISH was normal. The patient is adopted, so information about family history is limited, and no family members are available for testing. The patient was found to have a 158-kb deletion (122 probes in haploid state; minimum interval chr14:53,361,728–53,520,165; maximum interval chr14:53,352,059–53,520,859; based on UCSC 2006 hg18 assembly) involving 14q22.2 which deletes one copy of BMP4 (Fig. 2a). No other genes are present in the deleted region. Quantitative PCR data obtained with TaqMan probes confirmed deletion of one copy of BMP4 (Fig. 2b) and presence of both copies of OTX2 (data not shown).

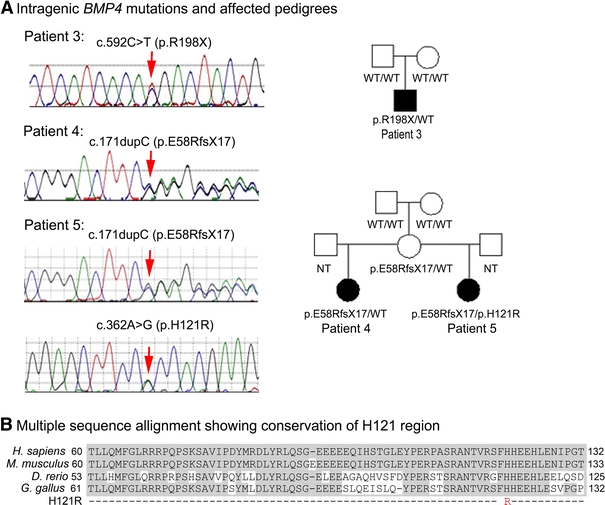

Patient 3 (Fig. 1e; Table 1) is a 19-month-old Caucasian male with right anophthalmia/severe microphthalmia, left mild microphthalmia with sclerocornea, facial asymmetry, and right-sided diaphragmatic hernia. His height and weight were normal at 11 weeks of age (60.4 cm/25th–50th centile and 6.8 kg/75th–90th centile, respectively), and by 19 months he was large for his age (90 cm/>97th centile and 13.3 kg/75th–90th centile). He has mild–moderate laryngomalacia with indentation from the innominate artery and bilateral inguinal hernias. He is developmentally normal with some minimal correction for his vision deficits. He has macrocephaly (43.5 cm at 11 weeks/ 90th–97th centile; 51 cm at 19 months/ >97th centile), a large anterior fontanelle, and hydrocephalus treated with a subdural-peritoneal shunt. Brain MRI at 4 months of age confirmed the ocular findings and showed macrocrania with very prominent subarachnoid spaces, superimposed overlying subdural collections as well as diffuse cerebral atrophy with ventricular prominence. Clinical chromosomal microarray (using Affymetrix Whole Genome-Human SNP Array 6.0) was normal. He was found to have a heterozygous c.592C>T (p.R198X) mutation, previously reported in cleft lip/palate (Suzuki et al. 2009) and predicted to result in premature termination of the BMP4 protein (Fig. 3a). Neither parent carries the mutation.

Fig. 3.

a Intragenic BMP4 mutations and affected pedigrees; mutation sites indicated with arrows. b Multiple sequence alignment of BMP4 amino acid sequences demonstrating conservation of the histidine affected in the identified H121R mutation. Shaded areas indicate conserved amino acids. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Homo sapiens NP_570911.2, Mus musculus AAH34053, Danio rerio AAH78423, Gallus gallus NP_990568

Patient 4 (Fig. 1f; Table 1) is a 3.5-year-old Caucasian female with bilateral clinical anophthalmia, small ears, and a small left renal cyst. Her birthweight was 3.35 kg (25th–50th centile), birth length was 49.5 cm (50th centile), and birth head circumference was 34 cm (50th centile). At 36 months, her weight was 11 kg (<3rd centile), and height was 93 cm (25th–50th centile). She has normal development, craniofacial features, hands, and feet. Head CT in the neonatal period showed significantly small globes, minimal ocular tissue, and absent optic nerves but otherwise normal brain structures. She was found to have a heterozygous c.171dupC (p.E58RfsX17) mutation (Fig. 3a).

Her 9-year-old maternal half-sister, Patient 5 (Fig. 1g; Table 1), is affected with unilateral anophthalmia (left), blepharophimosis and telecanthus and bilateral postaxial polydactyly of both hands. Her birthweight was 2.72 kg (25th centile), her length was 48 cm (25th centile), and her head circumference was 34 cm (50th centile). At 9 years, she demonstrates poor growth with height and weight <3rd centile (121 cm and 20 kg) and relative macrocephaly (75th centile) with frontal bossing. Her development is appropriate for age. Head CT showed atrophic left globe and small left orbit. Patient 5 was found to carry the same heterozygous c.171dupC (p.E58RfsX17) mutation along with a second variant, c.362A>G (p.H121R), in BMP4 (Fig. 3a, b). This variant was found to alter a conserved amino acid (Fig. 3b) and is predicted to be tolerated by SIFT (Ng and Henikoff 2003; http://sift.jcvi.org/) while probably damaging by PolyPhen-2 (Adzhubei et al. 2010; http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) analysis. Both the p.E58RfsX17 and p.H121R mutations affect exon 2 of BMP4 and were determined to be positioned on different alleles by PCR cloning and DNA sequencing of isolated alleles. The unaffected mother of Patients 4 and 5 was found to carry the p.E58RfsX17 mutation with no evidence of mosaicism (data not shown); the mutation apparently occurred de novo since the unaffected maternal grandparents of Patients 4 and 5 were found to carry wild-type BMP4 alleles. The unaffected father of Patient 5 was not available for testing. Neither parent was available for formal ophthalmological examination, so mild ocular anomalies could not be ruled out.

Screening of 179 Caucasian, 89 African American, 91 Asian, and 93 Hispanic control individuals did not identify any of the three coding region mutations discussed above.

Discussion

This is the first report of BMP4 deletion in a patient with the complete constellation of features comprising SHORT syndrome (Patient 1). SHORT syndrome was first described in 1975 and is characterized by Short stature, hyperextensibility of joints or inguinal Hernia, ocular depression, Rieger anomaly, and delay in dental eruption (Teeth) (Gorlin et al. 1975; Sensenbrenner et al. 1975). Autosomal dominant inheritance has been suggested (Koenig et al. 2003), but the genetic basis of SHORT syndrome is currently poorly understood. One case report identified a familial translocation, t(1;4)(q31.2;q25), presumably disrupting the PITX2 locus, in a child with SHORT syndrome and his mother with Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome and polycystic ovary syndrome (Karadeniz et al. 2004), but no other studies have replicated involvement of PITX2 in SHORT syndrome, which was also excluded in Patient 1 in this study.

Since the patient with SHORT syndrome (Patient 1) is affected with a deletion of the BMP4 region, we compared the “SHORT” deletion with other patient deletions of this region. Both BMP4 deletions reported in this study are smaller than the previously reported deletion of BMP4 without OTX2 involvement (Hayashi et al. 2008). Patient 2 (reported in this manuscript) with deletion of BMP4 only and the previously reported patient with a 2.7-Mb deletion involving BMP4 (Hayashi et al. 2008) did not demonstrate a SHORT syndrome phenotype. There are seven genes which are deleted in Patient 1 with SHORT syndrome, but not in Patient 2 or the patient presented by Hayashi et al. (2008): GNG2, NID2, C14orf166, PTGDR, PTGER2, TXNDC16, and GPR137C. Although none of these genes represents an obvious candidate for the observed phenotype based on current data (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim), SHORT syndrome may be a contiguous gene deletion syndrome which requires deletion of one (or more) of these genes in addition to BMP4.

Analysis of other phenotypic information presented in this manuscript as well as previously reported data further supports the role of BMP4 in SHORT syndrome. The association of BMP4 with anterior segment dysgenesis (Patients 2 and 3; Chang et al. 2001; Hayashi et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009), poor growth with height and/or weight measurements below the 3rd percentile (Patients 4 and 5; Hayashi et al. 2008), macrocephaly (Patients 3 and 5) and craniofacial/dental development in human patients (Patient 2; Suzuki et al. 2009) and animal models (Fujimori et al. 2010; Vainio et al. 1993; Zhang et al. 2000) is consistent with features of SHORT syndrome. The fact that other patients with BMP4 deletions/mutations do not demonstrate the full SHORT syndrome phenotype may be explained by variable phenotypic expressivity of BMP4 mutations and modification of their effect(s) by other genetic factors located elsewhere in genome. The observed incomplete penetrance/variable expressivity of BMP4 mutations and their wide phenotypic spectrum are in agreement with this possibility (Bakrania et al. 2008; Lubbe et al. 2011; Suzuki et al. 2009; Weber et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009). Screening of additional patients with SHORT syndrome is needed to determine the role/frequency of BMP4 mutations in this phenotype; in our study, one out of three patients diagnosed with this rare condition demonstrated BMP4 deletion.

The BMP4-positive phenotypes reported in this manuscript also show overlap with the Axenfeld–Rieger spectrum (Alward 2000; Rieger 1934, 1935; Shields et al. 1985) caused by mutations in the PITX2 and FOXC1 genes (Semina et al. 1996; Tümer and Bach-Holm 2009). This spectrum is characterized by ocular findings that include posterior embryotoxon, hypoplastic iris, irido-corneal adhesions and glaucoma and additional systemic defects such as craniofacial dysmorphism, dental hypoplasia and redundant periumbilical skin. Patient 1 (SHORT syndrome) has the characteristic Rieger anomaly in combination with atypical dental and umbilical anomalies, Patient 2 shows anterior segment dysgenesis and characteristic craniofacial dysmorphism including maxillary hypoplasia, and Patient 3 demonstrates anterior segment dysgenesis. Taken together with the potential role of both PITX2 (Karadeniz et al. 2004) and BMP4 (this paper) in SHORT syndrome, these data strongly suggest involvement of both factors in the same developmental processes. This is supported by previous studies in animal models which have shown that Bmp4 and Pitx2 act in a common pathway in craniofacial/dental and left–right asymmetry development (Liu et al. 2003; Lu et al. 1999; St Amand et al. 2000; Tsiairis and McMahon 2009). Specifically, Pitx2 was shown to be a repressor of Bmp4 expression (Liu et al. 2003; Lu et al. 1999), but Bmp4 was also able to repress Pitx2 expression (St Amand et al. 2000).

The c.171dupC (p.E58RfsX17) mutation identified in Patients 4 and 5 represents the most 5′ nonsense mutation reported to date and is expected to result in a complete loss of function. This allele is likely to result in an absence of protein product due to nonsense-mediated (NMD) decay of the mutant mRNA since the stop codon associated with this mutation is located more than 55 nt (152 nt) from the end of the second to last exon (Holbrook et al. 2004; Khajavi et al. 2006). If present, the mutated protein is predicted to be 14% of its normal length and lack the transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)-like domain and 91% of the TGFβ propeptide.

Our results further support the variable expressivity/incomplete penetrance of BMP4 mutations, as has been shown in previous publications (Bakrania et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2009; Weber et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009). While one previous family demonstrated a highly variable phenotype in association with a frameshift mutation (Bakrania et al. 2008), this is the first report of a loss-of-function mutation in an apparently unaffected parent (mother of Patients 4 and 5). In addition, only one patient in our group demonstrated digit anomalies and only one had a brain anomaly, both commonly reported in previously described cases with deletion/nonsense mutations. At the same time, new syndromes/features not described in earlier reports, such as SHORT syndrome, poor growth, macrocephaly, hydrocephalus, and diaphragmatic hernia, were identified. In addition, the nonsense mutation p.R198X, previously seen in a patient with cleft lip and palate and no details about additional features (Suzuki et al. 2009), was also seen in Patient 3 without cleft lip/palate in our study. None of our patients or the previously reported ocular cases demonstrated cleft lip/palate or family history of colorectal cancer, which have been previously reported in association with BMP4 alterations, primarily missense mutations (Lubbe et al. 2011; Suzuki et al. 2009).

The significance of the p.H121R variant seen in Patient 5 in combination with the p.E58RfsX17 is unclear. The histidine at position 121 is conserved (Fig. 3b), and the variant was neither seen in 452 controls reported here nor in 1,053 previously reported controls (Suzuki et al. 2009; Lubbe et al. 2011). Interestingly, Patient 5, with two mutations in BMP4, displays a milder ocular phenotype (unilateral anophthalmia) than her half-sister with the p.E58RfsX17 mutation only (bilateral anophthalmia), but has more severe digit involvement (polydactyly vs. normal hands/feet in Patient 4). Overall, the ocular and digit phenotypes observed in these half-siblings are consistent with the previously reported BMP4 spectrum, and therefore, it is difficult to determine the contribution of the p.H121R allele; it is possible that this variant represents a rare polymorphism. The unaffected father of this patient was not available for testing to determine whether the allele was inherited from an unaffected parent or occurred de novo.

A wide range of phenotypes have been reported in association with various mutations in BMP4, ranging from anomalies evident at birth to adult onset colorectal cancer. Since Bmp4 has been shown to have various roles in embryonic and adult tissues (Chang et al. 2001; Furuta and Hogan 1998; Hogan 1996; Jiao et al. 2003; Solnica-Krezel 1999; Wordinger et al. 2007), its involvement in multiple phenotypes is highly possible. Our data provide additional support for loss-of-function BMP4 mutations to be associated with syndromic ocular phenotypes. Each of the probands reported here and all but one of the previously reported cases with ocular phenotypes have mutations which result in lack of functional protein product (deletion or nonsense/frameshift mutations); in all but one of these cases in which family members were tested, the mutation was de novo or seen in affected family members only and loss-of-function BMP4 mutations have never been reported in control populations. In contrast, the majority of mutations associated with cleft lip and palate, renal anomalies, or colorectal cancer were missense mutations (Weber et al. 2008; Suzuki et al. 2009; Lubbe et al. 2011). While most of the reported missense mutations were not seen in control individuals and several modify conserved amino acids, in more than half of the cases in which family members were tested, the missense mutation was seen in an unaffected relative (8 of 13). This suggests the possibility that some of these missense variants represent rare polymorphisms rather than pathogenic mutations. At the same time, the number of rare BMP4 variants seen in patients with variable phenotypes may suggest a contributory/sensitizing role for BMP4 missense mutations leading to different phenotypes depending on other genetic variants/mutations present in the affected individuals. Additional mutational screens and identification of factors that may be involved in modification of the phenotypic expression of BMP4 mutations are needed to provide insight into the complexity of human phenotypes associated with BMP4 genotypes.

The results of this study confirm the role of BMP4 in developmental ocular anomalies, particularly anophthalmia/microphthalmia and anterior segment defects, and suggest that limb and brain anomalies may not be informative for determining which patients will benefit from molecular screening. Further screening for BMP4 mutations/deletions in patients with SHORT syndrome and a variety of ocular disorders will be important to further define the range of anomalies associated with mutations in/deletions of this gene.

Ethical standards All experiments performed comply with the current laws of the United States of America.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients and their families for their participation in research studies. We are also grateful to Robert Owens for helping with photography and to Rachel Lorier, Stephen Hall, Katie Felhofer and Andrea Lenarduzzie for assistance with Affymetrix array CNV analysis. This project was supported by award EY015518 from the National Eye Institute, and 1R21DC010912 from the National Institute of Hearing and Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health (EVS) and grant 1UL1RR031973 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health as well as two grants from the Mellon Mid-Atlantic Charitable Trusts, the Albert B. Millett Memorial Fund and the Rae S. Uber Trust, and a grant from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alward WL. Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome in the age of molecular genetics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:107–115. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakrania P, Efthymiou M, Klein JC, Salt A, Bunyan DJ, Wyatt A, Ponting CP, Martin A, Williams S, Lindley V, Gilmore J, Restori M, Robson AG, Neveu MM, Holder GE, Collin JR, Robinson DO, Farndon P, Johansen-Berg H, Gerrelli D, Ragge NK. Mutations in BMP4 cause eye, brain, and digit developmental anomalies: overlap between the BMP4 and hedgehog signaling pathways. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:304–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B, Smith RS, Peters M, Savinova OV, Hawes NL, Zabaleta A, Nusinowitz S, Martin JE, Davisson ML, Cepko CL, Hogan BL, John SW. Haploinsufficient Bmp4 ocular phenotypes include anterior segment dysgenesis with elevated intraocular pressure. BMC Genet. 2001;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori S, Novak H, Weissenbock M, Jussila M, Goncalves A, Zeller R, Galloway J, Thesleff I, Hartmann C. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the dental mesenchyme regulates incisor development by regulating Bmp4. Dev Biol. 2010;348:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuta Y, Hogan BL. BMP4 is essential for lens induction in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3764–3775. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlin RJ, Cervenka J, Moller K, Horrobin M, Witkop CJ., Jr Malformation syndromes. A selected miscellany. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1975;11:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Okamoto N, Makita Y, Hata A, Imoto I, Inazawa J. Heterozygous deletion at 14q22.1-q22.3 including the BMP4 gene in a patient with psychomotor retardation, congenital corneal opacity and feet polysyndactyly. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2905–2910. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins in development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:432–438. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook JA, Neu-Yilik G, Hentze MW, Kulozik AE. Nonsense-mediated decay approaches the clinic. Nat Genet. 2004;36:801–808. doi: 10.1038/ng1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K, Kulessa H, Tompkins K, Zhou Y, Batts L, Baldwin HS, Hogan BL. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karadeniz NN, Kocak-Midillioglu I, Erdogan D, Bokesoy I. Is SHORT syndrome another phenotypic variation of PITX2? Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:406–409. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khajavi M, Inoue K, Lupski JR. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig R, Brendel L, Fuchs S. SHORT syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2003;12:45–49. doi: 10.1097/00019605-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Selever J, Lu MF, Martin JF. Genetic dissection of Pitx2 in craniofacial development uncovers new functions in branchial arch morphogenesis, late aspects of tooth morphogenesis and cell migration. Development. 2003;130:6375–6385. doi: 10.1242/dev.00849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MF, Pressman C, Dyer R, Johnson RL, Martin JF. Function of Rieger syndrome gene in left-right asymmetry and craniofacial development. Nature. 1999;401:276–278. doi: 10.1038/45797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubbe SJ, Pittman AM, Matijssen C, Twiss P, Olver B, Lloyd A, Qureshi M, Brown N, Nye E, Stamp G, Blagg J, Houlston RS. Evaluation of germline BMP4 mutation as a cause of colorectal cancer. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:E1928–E1938. doi: 10.1002/humu.21376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen LD, Amor D, Haywood A, St Heaps L, Willcock C, Mihelec M, Tam P, Billson F, Grigg J, Peters G, Jamieson RV. Deletion at 14q22-23 indicates a contiguous gene syndrome comprising anophthalmia, pituitary hypoplasia, and ear anomalies. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1711–1718. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragge NK, Brown AG, Poloschek CM, Lorenz B, Henderson RA, Clarke MP, Russell-Eggitt I, Fielder A, Gerrelli D, Martinez-Barbera JP, Ruddle P, Hurst J, Collin JR, Salt A, Cooper ST, Thompson PJ, Sisodiya SM, Williamson KA, Fitzpatrick DR, van Heyningen V, Hanson IM. Heterozygous mutations of OTX2 cause severe ocular malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1008–1022. doi: 10.1086/430721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis LM, Tyler RC, Schneider A, Bardakjian T, Stoler JM, Melancon SB, Semina EV (2010) FOXE3 plays a significant role in autosomal recessive microphthalmia. Am J Med Genet A 152A(3):582–590. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rieger H. Verlagerung und Schlitzform der Pupille mit Hypoplasie des Irisvorderblattes. Z Augenheilkd. 1934;84:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger H. Beitraege zur Kenntnis seltener Missbildungen der Iris: ueber Hypoplasie des Irisvorderblattes mit Verlagerung und Entrundung der Pupille. Albrecht von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthal. 1935;133:602–635. doi: 10.1007/BF01853793. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schilter KF, Schneider A, Bardakjian T, Soucy JF, Tyler RC, Reis LM, Semina EV (2010) OTX2 microphthalmia syndrome: four novel mutations and delineation of a phenotype. Clin Genet 79(2):158–168. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01450.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Semina EV, Reiter R, Leysens NJ, Alward WL, Small KW, Datson NA, Siegel-Bartelt J, Bierke-Nelson D, Bitoun P, Zabel BU, Carey JC, Murray JC (1996) Cloning and characterization of a novel bicoid-related homeobox transcription factor gene, RIEG, involved in Rieger syndrome. Nat Genet 14:392–399. doi:10.1038/ng1296-392 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sensenbrenner JA, Hussels IE, Levin LS. A low birthweight syndrome, ? Rieger syndrome. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1975;11:423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields MB, Buckley E, Klintworth GK, Thresher R. Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome. A spectrum of developmental disorders. Surv Ophthalmol. 1985;29:387–409. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(85)90205-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solnica-Krezel L. Pattern formation in zebrafish—fruitful liaisons between embryology and genetics. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1999;41:1–35. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)60268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Amand TR, Zhang Y, Semina EV, Zhao X, Hu Y, Nguyen L, Murray JC, Chen Y. Antagonistic signals between BMP4 and FGF8 define the expression of Pitx1 and Pitx2 in mouse tooth-forming anlage. Dev Biol. 2000;217:323–332. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Marazita ML, Cooper ME, Miwa N, Hing A, Jugessur A, Natsume N, Shimozato K, Ohbayashi N, Suzuki Y, Niimi T, Minami K, Yamamoto M, Altannamar TJ, Erkhembaatar T, Furukawa H, Daack-Hirsch S, L’heureux J, Brandon CA, Weinberg SM, Neiswanger K, Deleyiannis FW, de Salamanca JE, Vieira AR, Lidral AC, Martin JF, Murray JC. Mutations in BMP4 are associated with subepithelial, microform, and overt cleft lip. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiairis CD, McMahon AP. An Hh-dependent pathway in lateral plate mesoderm enables the generation of left/right asymmetry. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1912–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tümer Z, Bach-Holm D. Axenfeld–Rieger syndrome and spectrum of PITX2 and FOXC1 mutations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1527–1539. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainio S, Karavanova I, Jowett A, Thesleff I. Identification of BMP-4 as a signal mediating secondary induction between epithelial and mesenchymal tissues during early tooth development. Cell. 1993;75:45–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S, Taylor JC, Winyard P, Baker KF, Sullivan-Brown J, Schild R, Knuppel T, Zurowska AM, Caldas-Alfonso A, Litwin M, Emre S, Ghiggeri GM, Bakkaloglu A, Mehls O, Antignac C, Network E, Schaefer F, Burdine RD. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordinger RJ, Fleenor DL, Hellberg PE, Pang IH, Tovar TO, Zode GS, Fuller JA, Clark AF. Effects of TGF-beta2, BMP-4, and gremlin in the trabecular meshwork: implications for glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1191–1200. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhao X, Yu X, Hu Y, Geronimo B, Fromm SH, Chen YP. A new function of BMP4: dual role for BMP4 in regulation of Sonic hedgehog expression in the mouse tooth germ. Development. 2000;127:1431–1443. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li S, Xiao X, Jia X, Wang P, Shen H, Guo X, Zhang Q. Mutational screening of 10 genes in Chinese patients with microphthalmia and/or coloboma. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2911–2918. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]