Abstract

We report on a case of cholesterosis bulbi concurrent with secondary glaucoma. A 36-year-old man, with a history of long-standing retinal detachment in his right eye after the irrigation and aspiration of a congenital cataract, presented with a clinical picture of elevated intraocular pressure and ocular pain. Upon slit-lamp examination, we found a ciliary injection and a pseudohypopyon of polychromatic crystals. Gonioscopic examination revealed a large amount of crystals deposited on the trabecular meshwork and mild rubeosis iridis, but the neovascularization of the angle could not be clearly confirmed due to the presence of so many crystals. Pars plana vitrectomy was performed to remove clusters of crystals and bevacizumab was injected intravitreally to treat iris neovascularization. Aqueous aspirate was examined by light microscopy and the typical highly refringent cholesterol crystals were identified. Intraocular pressure returned to a normal level after the bevacizumab injection, although severe cholesterosis was still evident in the anterior chamber. To our knowledge, this would be the first Korean case of cholesterosis bulbi combined with chronic retinal detachment and presumed neovascular glaucoma, which was treated by pars plana vitrectomy and intravitreal bevacizumab injection.

Keywords: Bevacizumab, Cholesterosis bulbi, Chronic retinal detachment, Secondary glaucoma

Cholesterol crystals of the anterior chamber is a rare condition that can be found as a marked feature of advanced cholesterosis bulbi [1]. Cholesterosis bulbi is known as a condition characterized by many crystalline bodies suspended in the vitreous body or the anterior chamber of blind eyes or those with long-term damage [2]. This condition can occur typically following long-standing retinal detachment (RD), severe ocular trauma, intraocular hemorrhage, advanced Coats' disease, etc [3,4].

A considerable number of cholesterosis bulbi cases have been treated by enucleation due to intractable pain and the further danger of sympathetic ophthalmia in the other eye [3-6]. Here, we report on the first Korean case of cholesterosis bulbi concurrent with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and rubeosis iridis, which was treated by pars plana vitrectomy, anterior chamber irrigation, and intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin), and include a review of the relevant literature.

Case Report

Initially, a 28-year-old man had visited our hospital complaining of poor vision and a white pupil in his right eye in August, 2001. He had been diagnosed as having a hypermature cataract, presumed to be congenital, and an exotropia of 40 prism diopters in his right eye. B-scan ultrasonography showed a flat retina without vitreous floaters in the right eye. Uncomplicated irrigation and aspiration without intraocular lens implantation and strabismus surgery had been performed on his right eye in September and October, 2001, respectively. The postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 0.02 in the right eye because of profound amblyopia and was 1.0 in the left eye. Postoperatively, the anterior segment was clear and the retina was flat with a long axial length of 30.45 mm in the right eye. His left eye was normal.

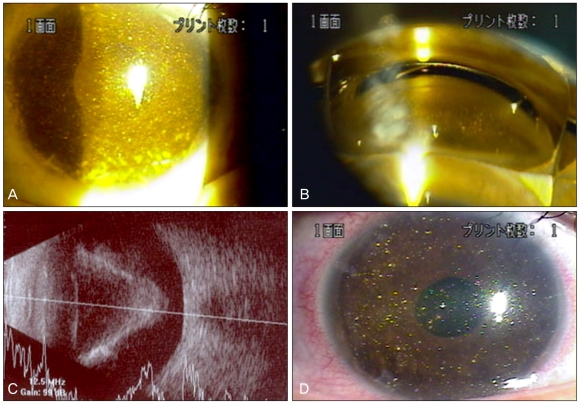

The subject was lost to follow-up for eight years, and revisited our clinic presenting with a two-month history of a painful, blind right eye in August, 2009. The BCVA was no light perception in the right eye and 1.0 in the left eye. Ophthalmologic examination revealed numerous polychromatic crystals in the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity, unilaterally elevated IOP (39 mmHg), mild rubeosis iridis, and surgical aphakia in his right eye. A huge quantity of crystals was floating in the anterior chamber according to eye movements, and some of the crystals were adhered to the iris surface or sedimented at the inferior angle, resembling a pseudohypopyon (Fig. 1A). On the gonioscopic view, the patient's trabecular meshwork was obscured by dense precipitates of crystals all over the angle and scattered peripheral anterior synechiae (Fig. 1B). A mild rubeosis iridis was evident near the pupil margin, but the neovascularization of the anterior chamber angle could not be clearly confirmed due to the presence of so many crystals near the angle. A funnel-shaped total RD was noted on the B-scan ultrasonograph (Fig. 1C). Our diagnoses were as follows: 1) cholesterosis bulbi accompanied by long-standing RD and 2) presumed neovascular glaucoma or secondary glaucoma associated with trabecular obstruction by crystals. The patient was in good health. Routine laboratory results, including serum lipid profiles, were within normal limits.

Fig. 1.

(A) Preoperative anterior segment photograph of affected eye. A huge amount of crystals was noted in the anterior chamber, and some of the crystals were adhered to the iris surface or sedimented at the inferior angle, resembling a pseudohypopyon. (B) On the gonioscopic view, the trabecular meshwork was obscured by dense precipitates of crystals all over the angle. (C) A funnel-shaped retinal detachment was found upon B-scan ultrasonography. (D) Anterior segment photograph at one week post-operative. Iris neovascularization had started to regress, but the amount of crystals in the anterior chamber had not decreased markedly as compared with the preoperative status, due to the continuous influx of cholesterol crystals from the vitreous cavity.

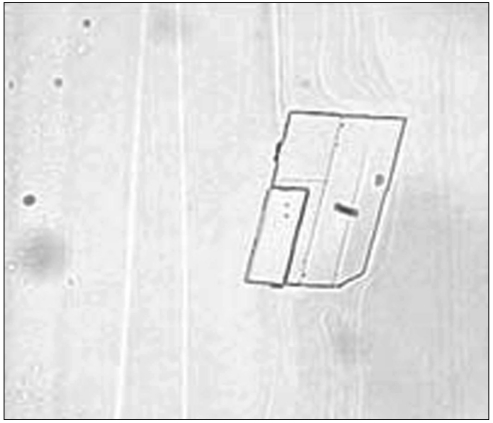

Anti-glaucoma medication failed to lower the IOP to a comfortable level in the patient's right eye. Pars plana vitrectomy and anterior chamber irrigation were performed to remove abundant crystal clumps, in conjunction with intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin, 2.5 mg / 0.1 mL) to diminish the neovascularization of the iris on the right eye. During the pars plana vitrectomy, we observed many crystals floating in the vitreous. Although there was total RD, we could not find any retinal breaks due to the hazy media and proliferative vitreoretinopathy changes in the retina. Despite our efforts, we could not remove the cholesterol crystals completely due to a continuous influx of the crystals. Microscopic analysis of the unprocessed aqueous humor aspirate disclosed transparent rhomboidal crystals with notched corners that are typical of cholesterol (Fig. 2). Calcium oxalate crystals were not found in the aqueous sample. A week after the surgery, the iris neovascularization started to regress, but the amount of crystals in the anterior chamber did not decrease markedly as compared with the preoperative status, due to the continuous influx of cholesterol crystals from the vitreous cavity (Fig. 1D). The IOP was still as high as 40 mmHg despite maximal medical treatment. A month after the surgery, the rubeosis iridis had completely disappeared and the IOP had decreased to normal range so that the patient could discontinue the administration of all of the IOP-lowering agents in the right eye. During the four months post-operative, the IOP in the right eye has been maintained at an adequate level.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic analysis of unprocessed aqueous humor aspirate disclosed transparent rhomboidal crystals with notched corners that are typical of cholesterol.

Discussion

Intraocular cholesterosis is a rare phenomenon that can occur in eyes that have undergone severe trauma, intraocular hemorrhage, severe inflammation, or chronic retinal detachment [5,7]. Forsius [3] reported on a typical microscopic photograph of cholesterol crystals in the aqueous humor of patients with cholesterosis bulbi. Also, a microscopic and chemical study by Kumar [6] suggested that the crystals in the anterior chamber were cholesterol. Andrews et al. [8] confirmed that the crystalline material observed in cases of cholesterosis bulbi was indeed cholesterol by thin-layer chromatography.

The concentration of cholesterol in normal vitreous was reported to be much lower than that in normal blood [8]. The major source of intraocular cholesterol crystals has been identified as degenerating extravascular blood [5,7]. Pathological changes in the blood-aqueous barrier may allow cholesterol to enter the vitreous or the anterior chamber, or it may enter via intraocular hemorrhages. Aphakia and lens subluxation can promote the anterior migration of cholesterol within the eye [9]. Kennedy [9] suggested that anterior chamber cholesterosis may develop in eyes with chronic retinal detachments in the absence of detectable intraocular hemorrhage. In such cases, it is likely that the crystals diffuse into the anterior chamber through retinal breaks from the subretinal fluid, which is rich in cholesterol [2,5]. In the same manner, Coats' disease with exudative retinal detachment can also be a cause of anterior chamber cholesterosis [4,10]. Finally, phacolysis is reported to be another source of the anterior chamber cholesterol crystals [9,11,12]. Hubbersty and Gourlay [12] described three cases of the anterior chamber crystals with lenticular origins that were associated with hypermature cataracts and lens capsular dehiscence.

In Korea, three cases of intraocular cholesterosis have been reported to our knowledge. Yu et al. [13] first reported a 16-year-old male patient who had anterior chamber cholesterosis in the high myopic and exotropic eye with a visual acuity of 0.1. He had not suffered from ocular trauma, retinal detachment, or intraocular surgery. The other two patients were reported by Shyn et al. [14]: a 25-year-old male patient, who had experienced a penetrating injury by a piece of metallic foreign body at the age of 13, underwent an intraocular foreign body removal and a lens extraction due to traumatic cataract; and a 21-year-old female patient had a long-standing cataract in the affected eye. The latter two patients had BCVAs of no light perception, and they had no evidence of retinal detachment. In all three cases, IOPs were normal and the typical cholesterol crystals in the aqueous aspirates were confirmed by wet field light microscopy.

Among the Korean cases, our patient is the only one that had cholesterosis bulbi following long-standing RD, which accompanied an elevated IOP. It is not certain which factors contributed to IOP elevation in our patient; the abundant cholesterol crystals that settled down at the anterior chamber angle could have caused an inflammatory reaction and disturbed the aqueous outflow, or the concurrent neovascularization of the iris and probably the angle by long-standing RD might have raised the IOP. After the pars plana vitrectomy, anterior chamber irrigation, and intravitreal injection of bevacizumab were performed in the affected eye, abundant crystals still existed in the anterior chamber, although their quantity was reduced as compared with the preoperative status. Therefore, we could not confirm the angle status or the regression of angle neovascularization by gonioscopy. However, iris neovascularization regressed completely, and IOP returned to the normal range. This suggests that the predominant mechanism responsible for the acute rise of IOP was the obstruction of the trabecular outflow by new vessels.

Historically, enucleation was mainly performed on patients with cholesterosis bulbi due to the absence of effective treatment, or out of concern for sympathetic inflammation of the other eye [3,5,6,13]. Eibschitz-Tsimhoni et al. [10] reported a case that had uncontrolled secondary open-angle glaucoma from the anterior chamber cholesterosis associated with Coats' disease. They suggested that the removal of the cholesterol crystals and treatment of the anomalous vessels by pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser photocoagulation may be sufficient to control the IOP. Our case showed that the treatment of the new vessels of the iris and anterior chamber angle and possibly abnormal retinal vessels by the injection of bevacizumab, which is a well-known antagonist of vascular endothelial growth factor, was useful for the management of secondary IOP elevation caused by new vessels. Reducing the amount of crystal clumps in the anterior chamber by pars plana vitrectomy might also have played a role. In summary, intravitreal injection of bevacizumab, combined with pars plana vitrectomy and anterior chamber irrigation, may be a viable alternative for enucleation in the treatment of cholesterosis bulbi accompanied by long-standing RD and presumed neovascular glaucoma, although a longer follow-up period will be required.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Mielke J, Freudenthaler N, Schlote T, Bartz-Schmidt KU. Pseudohypopyon of cholesterol crystals occurring 16 years after retinal detachment in x-linked retinoschisis. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2001;218:741–743. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wand M, Smith TR, Cogan DG. Cholesterosis bulbi: the ocular abnormality known as synchysis scintillans. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:177–183. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsius H. Cholesterol-crystals in the anterior chamber. A clinical and chemical study of 7 cases. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1961;39:284–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1961.tb00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shields JA, Eagle RC, Jr, Fammartino J, et al. Coats' disease as a cause of anterior chamber cholesterolosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:975–977. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100080025014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eagle RC, Jr, Yanoff M. Cholesterolosis of the anterior chamber. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1975;193:121–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00419356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S. Cholesterol crystals in the anterior chamber. Br J Ophthalmol. 1963;47:295–299. doi: 10.1136/bjo.47.5.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Vitreous hemorrhage. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;42:3–39. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)84041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews JS, Lynn C, Scobey JW, Elliott JH. Cholesterosis bulbi. Case report with modern chemical identification of the ubiquitous crystals. Br J Ophthalmol. 1973;57:838–844. doi: 10.1136/bjo.57.11.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy CJ. The pathogenesis of polychromatic cholesterol crystals in the anterior chamber. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1996;24:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1996.tb01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eibschitz-Tsimhoni M, Johnson MW, Johnson TM, Moroi SE. Coats' syndrome as a cause of secondary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2003;34:312–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruber E. Crystals in the anterior chamber. Am J Ophthalmol. 1955;40:817–827. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(55)91111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbersty FS, Gourlay JS. Secondary glaucoma due to spontaneous rupture of the lens capsule. Br J Ophthalmol. 1953;37:432–435. doi: 10.1136/bjo.37.7.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu YS, Kwak HW, Youn DH. Cholesterol crystals in the anterior chamber. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1980;21:117–119. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shyn KW, Koo JY, Lee YH. Two cases of cholesterosis bulbi. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;27:99–103. [Google Scholar]