Abstract

Objective

Decreasing the prevalence of severe postpartum haemorrhages (PPH) is a major obstetrical challenge. These are often considered to be associated with substandard initial care. Strategies to increase the appropriateness of early management of PPH must be assessed. We tested the hypothesis that a multifaceted intervention aimed at increasing the translation into practice of a protocol for early management of PPH, would reduce the incidence of severe PPH.

Design

Cluster-randomised trial

Population

106 maternity units in 6 French regions

Methods

Maternity units were randomly assigned to receive the intervention, or to have the protocol passively disseminated. The intervention combined outreach visits to discuss the protocol in each local context, reminders, and peer reviews of severe cases, and was implemented in each maternity hospital by a team pairing an obstetrician and a midwife.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was the incidence of severe PPH, defined as a composite of one or more of: transfusion, embolisation, surgical procedure, transfer to intensive care, peripartum haemoglobin delta of 4 g/dl or more, death. The main secondary outcomes were PPH management practices.

Results

The mean rate of severe PPH was 1.64% (SD0.80) in the intervention units and 1.65% (SD0.96) in control units; difference not significant. Some elements of PPH management were applied more frequently in intervention units –help from senior staff (p=0.005)-, or tended to – second line pharmacological treatment (p=0.06), timely blood test (p=0.09).

Conclusion

This educational intervention did not affect the rate of severe PPH as compared to control units, although it improved some practices.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT 00344929

Keywords: Maternal health, postpartum haemorrhage, clinical practices, educational intervention, cluster-randomised trial

Keywords: Clinical Protocols; Cluster Analysis; Education, Medical, Continuing; Female; France; Hospitals, Maternity; Humans; Incidence; Midwifery; education; Obstetrics; education; Patient Care Team; Postpartum Hemorrhage; epidemiology; prevention & control; Pregnancy; Professional Practice; standards; Sample Size; Treatment Outcome

Introduction

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) remains a leading cause of maternal mortality(1, 2) and the main component of severe maternal morbidity (3–5). Decreasing the prevalence of severe PPH is a major obstetrical challenge, in both developed and developing countries. Because individual risk factors do not predict PPH well(6, 7), interest has increasingly focused on factors related to the care provided, which are potentially more amenable to change.

In the area of prevention of PPH, a high level of evidence supports the efficacy of the routine administration of oxytocics during the third stage of labour (8) and the effective translation of these results into clinical practice through behavioural interventions has been recently described (9, 10). Conversely, improving obstetric care for the management of PPH remains difficult, although greatly needed. Reports from confidential enquiries into maternal deaths show that most deaths due to PPH involve delayed and substandard care in the diagnosis and management of haemorrhage (11–13). A population-based study of severe non-lethal PPH reached a similar conclusion (14). A recent study demonstrated a wide heterogeneity in maternity unit policies for the immediate management of PPH within individual European countries as well as between them (15, 16). These findings suggest that increasing the appropriateness of care should improve PPH-related health indicators. A number of PPH-related clinical guidelines have therefore been developed, both nationally and internationally (17–21).

The harder job, however, is ensuring the actual translation of these guidelines into clinical practice. Guidelines do not by themselves change professionals’ practices (22), and the effectiveness of active intervention strategies must be assessed. Results from educational interventions strictly focused on PPH prevention cannot be generalized to PPH management, because of the differential nature of care involved – routine versus emergency care. A few previous reports have described the effectiveness of local strategies in individual institutions aimed at improving the management of PPH (23, 24). The relevance of their results in other and more diverse settings is however questionable.

We present the results of a cluster-randomised controlled trial to test the hypothesis that a multifaceted educational intervention, aimed at improving practices for early PPH management, would reduce the rate of severe PPH in diverse obstetric care settings.

Methods

Design

The study was a cluster-randomised controlled trial, with the maternity unit as the randomisation unit. One group of maternity units was assigned to receive a multifaceted intervention to implement guidelines for PPH management. The control group of maternity units received no intervention.

Setting

The trial was conducted in six perinatal networks in France. A 1998 French statute aimed at optimising the organisation of obstetric care made it mandatory for all maternity units to belong to a perinatal network (25), organised around one or more level 3 units (reference centres with an onsite neonatal intensive care unit) and including units rated as level 1 (no facilities for non-routine neonatal care) and 2 (with a neonatal care unit), both public and private. The six perinatal networks were the Perinat Centre network around Tours (23 units), the Port-Royal St Vincent de Paul network in Paris (25 units), and the 4 networks of the Rhône-Alpes region: the Aurore network around Lyon (33 units), the Savoie network around Chambery (14 units), the Grenoble network (5 units), and the St-Etienne network (9 units).

Participants

Maternity units were eligible if they belong to one of the six networks. No other eligibility criterion was applied, in accord with our population-based approach. Two units were excluded because they were involved in a concomitant clinical study not compatible with our trial. One unit decided not to participate. Our sample therefore included 106 maternity units of the 109 in the six regional networks (listed in the Appendix). They accounted for about 17% of all French maternity units, and 20% of deliveries nationwide.

The trial took place between September 2004 and November 2005 in the Aurore network, and between September 2005 and November 2006 in the other five.

Randomisation

The random allocation was produced centrally by the Biostatistics department of the Hospices Civils de Lyon, France. A design stratified according to perinatal network and size was used to ensure that the two arms of the trial were as similar as possible at baseline. Perinatal network was divided into five classes, with the Grenoble and St-Etienne networks regrouped in one class because of their geographic proximity and small number of units. Size was classified in two categories: an annual number of deliveries equal to or greater than the 50th percentile for the network, or less than the 50th percentile. In each stratum, a balanced number of maternity units was assigned at random to one of the two arms (intervention or control). For each stratum, a random allocation was made using a random number generator available in SAS software, with a different seed value for each stratum.

Intervention

Protocol for early management of PPH

The protocol for stepwise management of PPH was consistent with the national clinical guidelines.(26) Overall, the main recommended steps were the following: examination of the uterine cavity and/or manual removal of placenta within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis; call for additional staff —obstetrician or anaesthetist —within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis; instrumental examination of the vagina and cervix; immediate intravenous administration of therapeutic oxytocin; and if PPH persisted, intravenous administration of sulprostone (second line oxytocic) within 30 minutes of the initial diagnosis, and a blood test within 60 minutes of it.

Intervention group

The multifaceted intervention consisted of a combination of three components —an outreach visit with academic detailing, reminders, and peer review of deliveries with severe PPH- to facilitate the translation into practice of the protocol for the early management of PPH.

For each network, an obstetrician and a midwife identified as opinion leaders in their professional community were teamed to implement the intervention’s components in each maternity unit. The demonstrated role of opinion leaders in facilitating the adoption of guidelines derives from their influence and power, as people of social importance.(27) These six teams met together during two one-day meetings for training in the different facets of the intervention.

The components of the intervention were implemented in two phases. The first phase lasted three months and consisted of outreach visits to each maternity unit (two visits per unit). During these visits, the team presented the key points of the protocol to the local target clinicians (obstetricians, midwives and anaesthetists) and discussed with them possible difficulties in its local implementation as well as potential solutions. This academic detailing is thought to facilitate changes in behaviours when it provides a clear message that meets the needs of the target audience (28–30). Each intervention unit received a colour poster summarising the key steps of the protocol. In addition, a specific “PPH chronological check list” was provided, a simple graphic reminder of the recommended steps for PPH management with a time scale on one side to be filled in by the care provider for each PPH case. Writing down the time of delivery, of PPH diagnosis, and of each procedure undertaken, as the event occurred, was intended to increase awareness of potential delay in care and as support for decision making in these cases. Behavioural and learning theories teach that change occurs if the stimuli precede the decision (28–30), and these reminders were thus intended to provide the stimuli. Finally, a “PPH box” was given to each unit. This box was intended to provide a single place where all drugs and materials needed for PPH management were available, as well as a list of useful phone numbers, forms for transfusion order and lab exams, and a chronometer to keep exact track of the time. The content of the box was locally discussed at the team meetings.

The second phase of the intervention was a peer review of deliveries with severe PPH, organised in each intervention unit. All cases of severe PPH identified during the first three months of data collection were reviewed during one meeting of the trial team with the local clinicians. The quality of care provided was critically analysed, and feedback on their practices provided to the local staff.

Reference group

In the maternity units of the reference group, the protocol for early management of PPH was presented at a staff meeting and passively disseminated. This occurred during the same time frame as the first phase of the intervention.

Definitions and Outcomes

PPH was clinically assessed by the care givers, or biologically defined by a peripartum haemoglobin delta greater than 2 g/dl (considered equivalent to the loss of more than 500 ml of blood). Prepartum haemoglobin was collected as part of routine prenatal care during the last weeks of pregnancy; postpartum haemoglobin was the lowest haemoglobin level found in the three days after delivery. The primary outcome for the trial was the rate of severe PPH, expressed as the number of deliveries with severe PPH divided by the total number of deliveries during the trial period. Severe PPH was defined as a PPH associated with one or more of the following events related to blood loss: blood transfusion, arterial embolisation, arterial ligation, other conservative uterine surgery, hysterectomy, transfer to intensive care unit, peripartum haemoglobin delta of 4 g/dl or more (considered equivalent to the loss of 1000 ml or more of blood), or maternal death. We chose the rate of severe PPH as the primary outcome because our primary goal was to assess the effect of the intervention on health and not only its impact on practices.

Secondary outcome measures included the rates of the principal interventions for PPH management recommended in the protocol: examination of the uterine cavity or manual removal of placenta or both within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis; call for an obstetrician or anaesthetist within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis; instrumental examination of the vagina and cervix; immediate intravenous administration of oxytocin; and when PPH persisted, intravenous administration of sulprostone within 30 minutes of the initial diagnosis, and a blood test for haemoglobin and haemostasis within 60 minutes. An additional secondary outcome measure was the PPH rate, expressed as the number of deliveries with PPH divided by the total number of deliveries during the trial period. Although the intervention focused mainly on PPH management, we also hypothesised that it might also improve practices of PPH prevention and lead to a decrease in the overall PPH rate.

According to the Kilpatrick Hierarchy for evaluation of educational programs(31), the present trial focused primarily on results evaluation (level IV of the Hierarchy) based on the rate of severe PPH, and on behavior evaluation (level III of the Hierarchy) through secondary outcomes related to actual practices for PPH management.

Data collection

Data collection began after the first phase of the intervention, and lasted for one year in both groups. All deliveries with PPH were prospectively identified by the birth attendants in each unit, who reported them to the research team. In addition, a research assistant reviewed the delivery suite logbook of each unit monthly, as well as computerised patient charts when available. For every delivery with a mention of PPH, or examination of the uterine cavity, or manual removal of the placenta (or any combination thereof), the patient’s obstetrics file was further checked to verify the PPH diagnosis.

A research assistant collected from the medical charts of every delivery with confirmed PPH the patient’s characteristics, those of the pregnancy, labour and delivery, and outcome data. The component procedures of PPH management were considered to have been performed only if they were specifically mentioned in the patient’s chart. The times of the different procedures/exams were extracted from the medical charts where they were written down by the care givers as events occurred. In cases where a procedure or an exam was performed but the time was not mentioned, it was recorded as “done but at unknown time”.

Sample size

The sample size estimation took into account the cluster-randomised design. We estimated the intra-cluster correlation coefficient to be 0.006. This estimation was derived from the rates of severe PPH provided by the 65 maternity units of five French regions for the year 2003 (Euphrates survey (16), secondary data analysis). On the assumption of a baseline rate of severe PPH of 1% of deliveries, 80% power, a two-sided test, a 0.05 significance level and an average cluster size of 1340 women, showing a decrease in the rate of severe PPH down to 0.6%, i.e. a relative risk reduction of 40%, would require 104 clusters (52 in each arm of the trial) reporting deliveries for one year to obtain a number of women of 139400 (32, 33). The average cluster size was determined according to the number of deliveries observed in maternity units of the six networks in 2002.

Analysis

Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, and all data from all maternity units assigned to the intervention or the control group were included in the analysis.

The primary outcome was expressed as the rate of severe PPH in each maternity unit, which was the unit of analysis. The difference between the mean rate of severe PPH between the intervention group and the control group was tested and quantified with a two-level logistic regression with a random intercept (34), which allowed us to take into account the natural hierarchical structure of the data with women clustered in maternity units. The intervention effect was quantified as an odds ratio with its 95% confidence interval. The intra-cluster correlation (ICC) coefficient, ρ, was calculated (35). The effect of the intervention on the primary outcome was tested in different subgroups according to characteristics of the maternity units (network, size, and status), or of the deliveries (vaginal or caesarean). These subgroup analyses were pre-specified in the protocol.

Secondary outcomes corresponding to procedures for PPH management were expressed as the percentage of each recommended practice among clinically diagnosed cases of PPH in each maternity unit. A two-level logistic regression with random intercept was used to test and quantify the intervention effect on secondary outcomes.

Primary and secondary outcomes were estimated for each of the four three month-time periods of the one year-inclusion period, The effect of time was tested in the intervention and control groups separately, using a two level logistic regression with the time period as a categorical explanatory variable, first time period being the reference category. In a second step, a two-level logistic regression including all the maternity units was built to quantify the evolution of the primary and secondary outcomes according to the time period introduced as an ordinal variable. An interaction term between the period variable and the intervention was introduced in the model to quantify the intervention effect on this evolution.

The threshold for statistical significance was set up at a probability value of <0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata v10.0 software (Stata Corporation, College station, Texas, USA) and R software version 2.8.1.

Results

Characteristics of maternity units

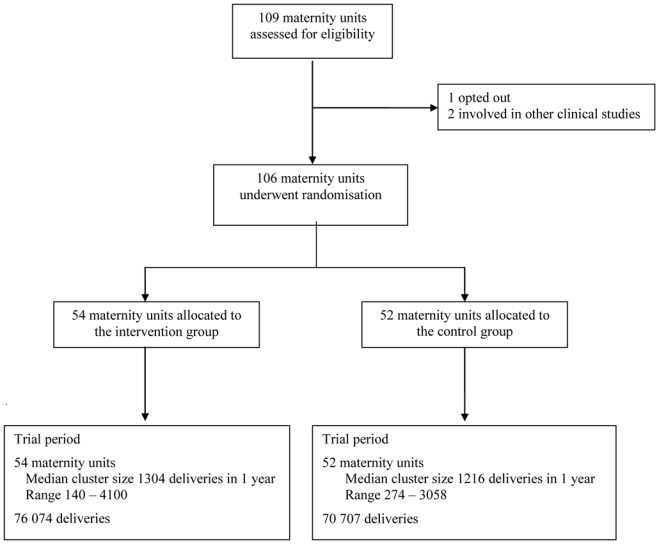

Fifty-four units were allocated to the intervention group, and 52 to the control group. Once entered, all 106 units completed the trial (Figure 1). The characteristics of the units in each group were similar (Table 1), in particular with regard to factors that affect the PPH risk (multiple pregnancy and caesarean delivery rates) and resources likely to influence the content of care provided for PPH (on-site embolisation, intensive care unit, presence of anaesthetist).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of randomised maternity units by allocation

| Intervention group N= 54 |

Control group N= 52 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Perinatal network | 1 | 17 | 31.5 | 16 | 30.8 |

| 2&3 | 8 | 14.8 | 6 | 11.5 | |

| 4 | 6 | 11.1 | 8 | 15.4 | |

| 5 | 11 | 20.4 | 11 | 21.1 | |

| 6 | 12 | 22.2 | 11 | 21.1 | |

| Annual number of deliveries | <500 | 7 | 13.0 | 8 | 15.4 |

| 500–1499 | 27 | 50.0 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| ≥1500 | 20 | 37.0 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| Status of maternity unit | University public | 6 | 11.1 | 6 | 11.5 |

| Other public | 31 | 57.4 | 28 | 53.8 | |

| Private | 17 | 31.5 | 18 | 34.6 | |

| Level of care* | 1 | 33 | 61.1 | 27 | 51.9 |

| 2 | 16 | 29.6 | 22 | 42.3 | |

| 3 | 5 | 9.2 | 3 | 5.8 | |

| 24/24 on-site anaesthetist | 43 | 79.6 | 39 | 75.0 | |

| On-site arterial embolisation | 10 | 18.5 | 11 | 21.1 | |

| Intensive care unit in hospital | 26 | 30 | 55.6 | 26 | |

| Policy of systematic haemoglobin measurement postpartum | 6 | 7 | 12.9 | 6 | |

| Mean (sd) (min, max) | Mean (sd) (min, max) | ||||

| Rate of caesarean delivery (%) | 20.2 (4.2) (11.1; 28.8) | 20.0 (4.7) (11.8; 34.0) | |||

| Rate of multiple pregnancy (%) | 1.1 (0.7) (0.0;2.9) | 1.3 (0.9) (0.0;4.6) | |||

level of care: 1= no facilities for non-routine neonatal care; 2= with a neonatal care unit; 3= with an onsite neonatal intensive care unit

Outcome measures

The trial period covered 76 074 deliveries in the intervention group and 70 707 in the control group. The median annual number of deliveries per unit was 1304 in the intervention units and 1216 in the control units (p=0.94, Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test result).

The mean rate of severe PPH did not differ between the intervention units (1.64%, SD 0.80) and the control units (1.65%, SD 0.96) (Table 2). The intra-cluster correlation coefficient for severe PPH was 0.0034. This lack of difference for the primary outcome between the two groups was consistent across networks, size categories, statuses, and modes of delivery.

Table 2.

Effect of the multifaceted intervention on the mean rate of severe PPH (primary outcome) and the mean rate of all PPH

| Outcome | Intervention n = 54 units |

Control n = 52 units |

OR (95% CI)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean rate (sd) (min, max) | mean rate ( sd) (min, max) | ||

| Severe PPH1 (% of deliveries) | 1.64 (0.80) (0.00;3.84) | 1.65 (0.96) (0.29;4.29) | 1.02 (0.83;1.24) |

| Main components of severe PPH | |||

| Blood transfusion (% of deliveries) | 0.44 (0.30) (0.00;1.00) | 0.41 (0.31) (0.00; 1.47) | 1.13 (0.88; 1.44) |

| Peripartum Hb delta ≥4g/dl (% of deliveries) | 1.49 (0.75) (0.00;3.83) | 1.44 (0.88) (0.15;3.95) | 1.05 (0.86;1.29) |

| All PPH (% of deliveries) | 6.37 (3.63) (1.95;22.05) | 6.37 (4.16) (1.52;17.63) | 1.01 (0.8;1.3) |

severe PPH defined by one of the following: maternal death, transfusion, surgery/embolisation, transfer to intensive care unit, peripartum hemoglobin delta ≥ 4g/dl.

hierarchical logistic regression model with a random intercept

Analyses tested the effect of the intervention on the main components of the primary outcome (Table 2). The groups did not differ in their proportions of blood transfusions and of women with peripartum haemoglobin delta of 4g/dl or more. No significant difference was found between the two groups in the rate of the other components of the primary composite outcome: the mean rates were 0.09% (SD 0.15) and 0.10% (SD 0.21) for embolisation for PPH, 0.04% (SD 0.05) and 0.04% (SD0.07) for conservative uterine surgery, 0.05% (SD 0.07) and 0.04% (SD 0.06) for hysterectomy, and 0.16 % (SD0.15) and 0.16 (SD 0.22) for transfer to ICU, in the intervention and control groups, respectively (data not shown).

Finally, the mean PPH rate was similar in the intervention and control units, 6.37% (SD 3.63) and 6.37% (SD 4.16) of deliveries, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of the multifaceted intervention on management of PPH1

| Procedures for PPH management | Intervention n = 54 |

Control n = 52 |

OR (95% CI)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| mean rate (sd) (min, max) | mean rate (sd) (min, max) | ||

| Examination of uterine cavity and/or manual removal of placenta3 | 75.9 (15) (30.8, 97.6) | 76.3 (13.4) (42.9, 100) | 0.97 (0.71; 1.32) |

| Examination of uterine cavity and/or manual removal of placenta within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis3, 4 | 53.2 (16.9) (15.4, 96) | 49.5 (19.5) (0, 81.6) | 1.05 (0.79; 1.4) |

| Instrumental examination of vagina and cervix3 | 28.8 (17.2) (0, 69.8) | 24.08 (18.7) (0, 66.7) | 1.26 (0.87; 1.81) |

| Call for help from senior staff | 79.9 (14.7) (42.7, 100) | 71.2 (19.1) (27.8, 100) | 1.65 (1.17; 2.33) |

| Call for help from senior staff within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis4 | 67.0 (17.3) (27.6, 100) | 58.4 (19.4) (17.6, 100) | 1.48 (1.05; 2.09) |

| Administration of oxytocin | 92.2 (6.6) (76.5, 100) | 91.9 (8.6) (52.9, 100) | 0.92 (0.63; 1.33) |

| In severe PPH5 | |||

| Administration of sulprostone6 | 48.7 (25.3) (0, 100) | 39.9 (26.0) (0, 100) | 1.45 (0.99; 2.13) |

| Administration of sulprostone6within 30 minutes of PPH diagnosis4 | 24.2 (17.5) (0, 75.0) | 16.9 (15.9) (0, 51.9) | 1.39 (0.96; 2.00) |

| Blood test for haemoglobin and haemostasis within 60 minutes of PPH diagnosis4 | 37.5 (20.5) (0, 87.5) | 28.4 (22.1) (0, 80.0) | 1.36 (0.95; 1.94) |

analysed among cases of PPH that were clinically diagnosed (n= 3107 in intervention group and 3554 in control group)

hierarchical logistic regression model with a random intercept

PPH after vaginal deliveries

data on time of procedure were missing in 19.1% of cases for examination of uterine cavity, 2.4% for call for extra help, 2.6 % for administration of sulprostone, and 10.2% for blood test.

PPH with one of the following: maternal death, transfusion, surgery/embolisation, ICU, peripartum hemoglobin delta ≥ 4g/dl.

PPH due to uterine atony or retained placenta

Some elements of PPH management were applied more frequently in intervention units (Table 3): calling for help from senior staff (mean rate 79.9% (SD14.7) and 71.2% (SD19.1) in intervention and control units respectively; p=0.005), call for senior help within 15 minutes of PPH diagnosis (mean rate 67.0% (SD17.3) and 58.4% (SD19.4) in intervention and control units respectively; p=0.009). Other elements of PPH management tended to be apply more frequently in intervention units although the difference did not reach statistical significance: administration of sulprostone in severe PPH due to uterine atony or retained placenta (mean rate 48.7% (SD25.3) and 39.9% (SD26.0) in intervention and control units respectively; p=0.06), administration of sulprostone within 30 minutes of PPH diagnosis (mean rate 24.2% (SD17.5) and 16.9% (SD15.9) in intervention and control units respectively; p=0.08), blood test within 60 minutes of diagnosis in severe PPH (mean rate 37.5% (SD20.5) and 28.4% (SD22.1) in intervention and control units respectively; p=0.09).

There was no difference between the two groups in the rate of oxytocin administration for PPH, or in the prevalence of examination of the uterine cavity and of instrumental examination of the vagina and cervix in PPH after vaginal delivery (Table 3).

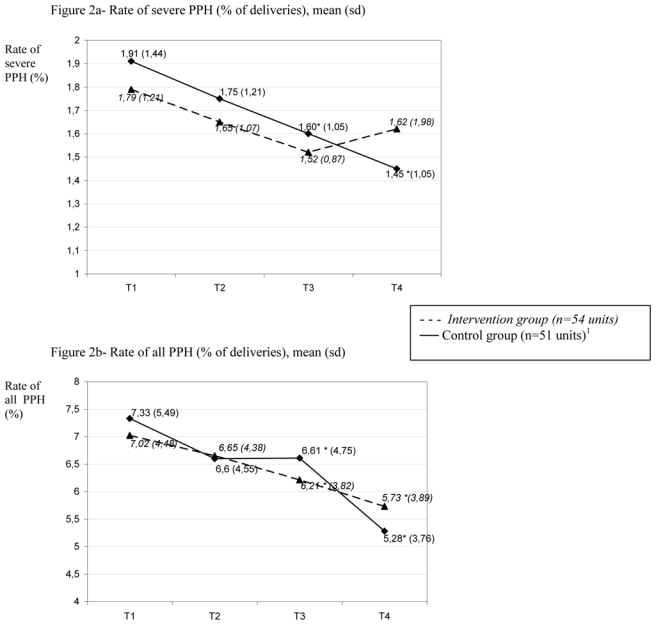

Figure 2 shows the trends over time of the rate of severe PPH and of all PPH during the one-year trial period in each group. In the intervention units, the mean rate of severe PPH decreased between the first and third time periods (1.79% (SD 1.21) and 1.52% (SD 0.87) respectively; p=0.07); compared with the first time period (7.02% (SD 4.48), the mean rate of all PPH was significantly lower in both the third (6.21% (SD 3.82); p=0.005) and fourth (5.73% (SD 3.89); p=0.001) time periods. In the control units, the mean rate of severe PPH was significantly lower in both the third and fourth time periods than in the first period (1.60% (SD 1.05), 1.45% (SD 1.05) and 1.91% (SD1.44) respectively; p=0.01 and 0.03); compared with the first time period(7.33% (SD 5.49), the mean rate of all PPH was significantly lower in the third (6.61% (SD 4.75); p=0.04) and fourth (5.28% (SD 3.76); p=0.001) periods.

Figure 2. Mean rate of severe PPH and of all PPH by allocation group and time periods of trial (T1 to T4).

1 data on number of deliveries by trimester not available in one unit

* p<0.05 for test of difference from mean rate in first trimester.

The trend of decrease with time period of the rate of severe PPH and all PPH was not significantly different between the intervention group and the control group (no significant interaction; p=0.94 and 0.35 respectively). The trends over time of the main components of the primary outcome were further analysed (data not shown). The rate of deliveries with peripartum haemoglobin delta of 4g/dl or more decreased significantly during the one year study period in maternity units of the 2 arms, and this trend was not different between the 2 groups. In the intervention arm, the rates of transfusion, of surgery and of embolisation did not decrease over time. In the control group, a significant reduction over time in the rates of transfusion and of surgery was found.

Discussion

This trial, involving 106 maternity units and 146 781 parturient women, tested the impact of an educational intervention to improve the translation into clinical practice of guidelines for PPH management. Although no significant difference was found in the primary outcome between the two groups, we think this trial contributes substantially to the debate on effective strategies to improve care of women with PPH and reduce the incidence of its most severe forms.

Two studies have reported successful interventions to implement changes in the management of women with PPH. In one hospital in Dublin, the incidence of massive PPH decreased significantly from 1.7% in 1999 to 0.45% in 2002 following revision of the guidelines for PPH management, their dissemination to staff, and use of practice drills (23). Another report from a hospital in New York described how a systemic approach to improving the safety of patients with PPH was adopted in late 2001 and reported that it was associated with fewer maternal deaths due to PPH in 2002–2005 than in 2000–2001, despite a significant increase in major obstetric haemorrhage cases (24). These interventions were, however, conducted in single institutions. Whether their approach can be replicated in other units is especially uncertain given the importance of local context in the process of improving practices (29, 30). In addition, the before/after design of these studies made it difficult to control for potential confounders, and factors external to the intervention may have accounted for the reported improvements in outcomes.

In the present randomized trial, , the rates of PPH and severe PPH tended to be lower in both groups in subsequent time periods than in the first three month-period of assessment. This suggests that the intervention may have had a concomitant effect in the control group, and that this parallel effect contributed to the absence of a major difference between the two arms of the trial. This finding is particularly notable in view of recent reports of increases in PPH prevalence from several countries (36–38). Some control units may have been “contaminated” by the intervention implemented in units with which they were in contact. It is also possible that participation in the trial and reporting PPH cases triggered individual changes in behaviours in clinicians of control units. Participation in a research study, independently of any specific intervention, has been reported to change behaviours of participants (Hawthorne effect (39)). The significant decrease in the prevalence of all PPH in control as well as intervention units probably also reflects an improvement in prevention strategies during the third stage of labour; however, assessing such an effect would require a representative sample of all deliveries.

The educational intervention had no additional impact on the rate of severe PPH in intervention units. It is clear that the content of the intervention was lighter and shorter than other behavioural interventions that have been proven to effectively modify obstetric practices (13, 40). It was designed to be easily reproducible. It may however have been insufficient to lead to major improvement of practices. In particular, repeating the peer reviews of severe PPH cases might have had a greater impact. It is also possible that the intervention components chosen, derived from previous reports focusing on routinely administered care, were not the most relevant for improving practices related to a rare obstetric emergency such as PPH. Changes may be more likely in systematic practices, that is, those applicable to all patients, such as preventive or diagnostic practices, than in practices related to more unusual situations for which other strategies, such as practice drills, may be more relevant. Furthermore, guidelines for PPH management, unlike those for its prevention, do not have a strong evidentiary basis and rely mostly on professional consensus. This lack of evidence may favour non-standardised clinical practices. Finally, it may be hypothesized that the risk of severe PPH is influenced mainly by factors other than the early management of excessive bleeding, such as interventions during labour or delivery, or characteristics of care organization. More etiological studies are needed to identify what factors influence the development of severe PPH in the presence of excessive bleeding.

This study had some limitations. The definition of severe PPH was based partly on PPH management components that may have been affected by the intervention, although the primary target was early management. However, because the rate of women with peripartum haemoglobin delta of 4g/dl or more, a biological marker of severe blood loss, was similar in both groups, this bias, if present, was probably minor and is unlikely to explain the absence of difference in primary outcome between the two arms.

It is also possible that the national context at the time of the trial was not optimal for controlled testing of the impact of an educational intervention targeting practices for PPH management. Obstetrics professionals in France have been focusing increasingly on the issue of PPH since the late 1990s, and global improvement in PPH-related practices might have been underway, although we lack the data to document this. This possibility illustrates the ambiguity of cluster-randomised trials. The design provides better external validity than individual randomisation because the “real” general context of care is maintained, but for the same reason, it is difficult to control for factors external to the intervention that may affect outcomes.

Conclusion

In this randomised trial, changes in outcomes occurred in both groups. However, the educational intervention was not associated with a significant additional impact on the rate of severe PPH as compared to control units. These results illustrate the challenge of designing and evaluating behavioural interventions to improve clinical practices. Yet, as more evidence on the efficacy of components of care becomes available, such programs are increasingly needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Gerard Bréart for his scientific advice; Sylvie Baumard, Sophie Gariod, Laurence Pavie and Thomas Schmitz for their contribution to the intervention implementation; Laetitia Bouveret, Emmanuelle Garreta, Dina Goma, Laurence Lecomte, Corinne Martinella, Blandine Masson, Stephanie Moret, Myriam Tapella and Typhaine Verzeele for their contribution to data collection and entry; Alvine Bissery for her contribution to data cleaning and analysis; and staff from the participating maternity units: Aurore perinatal network: Clinique d’Amberieu en Bugey, Centre Hospitalier de Bourg en Bresse, Centre Hospitalier d’Oyonnax, Centre Hospitalier d’Aubenas, Clinique Pasteur (Valence), Centre Hospitalier de Privas, Centre Hospitalier de Die, Centre Hospitalier de Montélimar, Centre Hospitalier de Romans sur Isère, Centre Hospitalier de Valence, Clinique Générale (Valence), Centre Hospitalier de Bourgoin Jallieu, Clinique Saint Vincent de Paul (Bourgoin Jallieu ), Clinique de Roussillon, Centre Hospitalier de Vienne, Clinique de Villefranche sur Saône, Clinique Champfleuri (Décines), Clinique du Val d’Ouest (Ecully), Centre Hospitalier de Givors, Centre Hospitalier La Croix-Rousse (Lyon), Centre Hospitalier Hôtel Dieu (Lyon), Centre Hospitalier Edouard Herriot (Lyon), Clinique Monplaisir (Lyon), Centre Hospitalier St Luc St Joseph (Lyon), Centre Hospitalier Lyon Sud, Clinique de Rilleux La Pape, Clinique Trenel (Vienne), Centre hospitalier de Ste Foy Les Lyon, Clinique Pasteur (St Priest), Clinique de l’union (Vaulx en Velin), Clinique de la Roseraie et des minguettes (Vénissieux), Centre Hospitalier de Villefranche sur Saône, Clinique du Tonkin (Villeurbanne); Alpes Isere perinatal network: Centre Hospitalier de Voiron, Centre Hospitalier Nord (Grenoble), Clinique Belledonne (Grenoble), Clinique des Cèdres (Grenoble), Clinique des eaux claires (Grenoble); Loire Nord Ardeche perinatal network: Centre Hospitalier d’Annonay, Centre Hospitalier de Feurs, Centre Hospitalier de Firminy, Centre Hospitalier de St Chamond, Centre Hospitalier de Montbrison, Centre Hospitalier de Roanne, Centre Hospitalier de St Etienne, Clinique Michelet (Saint Etienne), Centre Hospitalier de Moze; 2 Savoie perinatal network: Centre Hospitalier d’Aix les Bains, Centre Hospitalier d’Albertville, Centre Hospitalier d’Annemasse Bonneville, Clinique de Savoie (Annemasse), Centre Hospitalier d’Annecy, Clinique Generale (Annecy), Centre Hospitalier de Belley, Centre Hospitalier de Bourg St Maurice, Centre Hospitalier de Chambery, Clinique de l’Esperance (Cluses), Centre Hospitalier du Léman (Thônon-Evian les bains), Centre Hospitalier de St Julien en Genevois, Centre Ho spitalier de St Jean de Maurienne, Centre Hospitalier du Mont Blanc (Sallanches-Chamonix); Port-Royal St Vincent de Paul perinatal network: Centre Hospitalier Cochin (Paris), Centre Hospitalier de Nanterre, Centre Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière (Paris), Clinique Isis (Paris), Centre Hospitalier Les Diaconesses (Paris), Centre Hospitalier Saint-Antoine (Paris), Centre Hospitalier Les bluets (Paris), Clinique du Mousseau (Evry), Centre Hospitalier de Juvisy, Centre Hospitalier Beaujon (Paris), Centre Hospitalier Louis Mourier (Colombes), Clinique Lambert (La Garenne Colombes), Centre Hospitalier de Courbevoie-Neuilly, Clinique Ste Isabelle (Neuilly), Clinique les Martinets (Rueil Malmaison), Centre Hospitalier de St Cloud, Centre Hospitalier Jean Rostand (Sèvres), Centre Hospitalier Foch (Suresnes), Hôpital privé Armand Brillard (Nogent sur Marne ), Centre Hospitalier Bégin (Vincennes), Hôpital privé Nord parisien (Sarcelles), Maternité des Lilas; PerinatCentre perinatal network: Clinique Guillaume deVayre (Saint Doulchard), Centre Hospitalier de Bourges, Centre Hospitalier de Vierzon, Centre Hospitalier de St Amand Montrond, Centre Hospitalier de Chateaudun, Clinique St Francois (Chateauroux), Centre Hospitalier de Chartres, Centre Hospitalier de Chateauroux, Centre Hospitalier de Le Blanc, Clinique St Francois ( Mainvillers), Clinique du Parc (Chambray), Centre Hospitalier de Chinon, Centre Hospitalier de Tours, Centre Hospitalier de Dreux, Centre Hospitalier de Blois, Clinique St Coeur (Vendôme), Clinique St Come (Blois), Centre Hospitalier de Romorantin, Centre Hospitalier d’Orleans, Centre Hospitalier de Pithiviers, Polyclinique des longues allées (Saint Jean de Braye), Centre Hospitalier de Montargis, Centre Hospitalier de Gien.

Funding

The project was funded by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program (contract no 27-35). The Ministry had no role in the design of the trial, the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interests and Contribution to authorship

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the central monitoring of data collection, the cleaning and analysis of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest. I confirm that I had full access to the data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Catherine Deneux-Tharaux

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the central monitoring of data collection, the cleaning and analysis of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

Corinne Dupont

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the analysis of the data, and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

Cyrille Colin

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the cleaning and analysis of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

M Rabilloud

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the analysis of the data, and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

S Touzet

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the analysis of the data, and the revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

J Lansac

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial and the revision of the draft paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

T Harvey

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial and the revision of the draft paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

V Tessier

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial and the revision of the draft paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

C Chauleur

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial and the revision of the draft paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

G Pennehouat

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial and the revision of the draft paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

X Morin

I declare that I participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the analysis of the data, and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

Marie-Hélène Bouvier-Colle

I declare that I initiated the collaborative project, participated in the design of the trial, the implementation of the trial, the analysis of the data and the drafting and revision of the paper and that I have seen and approved the final version. I have no conflicts of interest.

René Rudigoz

Ethics approval

Approval for the study was obtained from the Sud Est III Institutional Review Board and from the French Data Protection Agency (CNIL). Because outcome data were routinely collected at maternity units, and anonymously transmitted, no individual consent was needed.

References

- 1.Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1066–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildman K, Bouvier-Colle MH. Maternal mortality as an indicator of obstetric care in Europe. Bjog. 2004;111(2):164–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00034.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Feb 14; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, Heaman M, Baskett T, Rusen ID, et al. Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991–2001. Cmaj. 2005 Sep 27;173(7):759–64. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang WH, Alexander S, Bouvier-Colle MH, Macfarlane A. Incidence of severe pre-eclampsia, postpartum haemorrhage and sepsis as a surrogate marker for severe maternal morbidity in a European population-based study: the MOMS-B survey. Bjog. 2005;112(1):89–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK., Jr Factors associated with postpartum hemorrhage with vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magann EF, Evans S, Hutchinson M, Collins R, Howard BC, Morrison JC. Postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal birth: an analysis of risk factors. South Med J. 2005 Apr;98(4):419–22. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000152760.34443.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elbourne DR, Prendiville WJ, Carroli G, Wood J, McDonald S. Prophylactic use of oxytocin in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD001808. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Althabe F, Buekens P, Bergel E, Belizan JM, Campbell MK, Moss N, et al. A behavioral intervention to improve obstetrical care. N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358(18):1929–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa071456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Figueras A, Narvaez E, Valsecia M, Vasquez S, Rojas G, Camilo A, et al. An education and motivation intervention to change clinical management of the third stage of labor - the GIRMMAHP Initiative. Birth. 2008 Dec;35(4):283–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapport du Comité National d’Experts sur la Mortalité Maternelle (CNEMM) France: 2006. http://www.invs.sante.fr/publications/2006/mortalite_maternelle/rapport.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouvier-Colle MH, Varnoux N, Breart G. Maternal deaths and substandard care: the results of a confidential survey in France. Medical Experts Committee. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995 Jan;58(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)01976-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis G. Saving mother’s lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer-2003–2005. the seventh report of the Confidential Enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bouvier-Colle MH, Ould El Joud D, Varnoux N, Goffinet F, Alexander S, Bayoumeu F, et al. Evaluation of the quality of care for severe obstetrical haemorrhage in three French regions. Bjog. 2001;108(9):898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winter C, Macfarlane A, Deneux-Tharaux C, Zhang WH, Alexander S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Variations in policies for management of the third stage of labour and the immediate management of postpartum haemorrhage in Europe. Bjog. 2007 Jul;114(7):845–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deneux-Tharaux C, Dreyfus M, Goffinet F, Lansac J, Lemery D, Parant O, et al. Prevention and early management of immediate postpartum haemorrhage: policies in six perinatal networks in France. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2008 May;37(3):237–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goffinet F, Mercier F, Teyssier V, Pierre F, et al. Collège national des gynécologues et obstétriciens français, Agence nationale d’Accréditation et d’Evaluation en Santé. Postpartum haemorrhage: recommendations for clinical practice by the CNGOF (December 2004) Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005 Apr;33(4):268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of health New South Wales Government Australia. Postpartum haemorrhage- framework for prevention, early recognition and management. 2005. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/PD/2005/PD_264.html.

- 19.National Guideline Clearinghouse. Postpartum haemorrhage. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006. http://www.guideline.gov/summary/pdf.aspx?doc_id=10922&stat=1&string= [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. 2000. http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/public/88E-CPG-April2000.pdf.

- 21.World Health Organization. Managing postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/2_9241546662/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomas J, Anderson GM, Domnick-Pierre K, Vayda E, Enkin MW, Hannah WJ. Do practice guidelines guide practice? The effect of a consensus statement on the practice of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1989 Nov 9;321(19):1306–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198911093211906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizvi F, Mackey R, Barrett T, McKenna P, Geary M. Successful reduction of massive postpartum haemorrhage by use of guidelines and staff education. Bjog. 2004 May;111(5):495–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skupski DW, Lowenwirt IP, Weinbaum FI, Brodsky D, Danek M, Eglinton GS. Improving hospital systems for the care of women with major obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):977–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000215561.68257.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.French ministry of health. Décret 98-899. 1998. http://wwwsante-jeunesse-sportsgouvfr/fichiers/bo/1998/98-50/a0503153htm.

- 26.Goffinet F, Mercier F, Teyssier V, Pierre F, Dreyfus M, Mignon A, et al. Postpartum haemorrhage: recommendations for clinical practice by the CNGOF (December 2004) Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005 Apr;33(4):268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lomas J, Enkin M, Anderson GM, Hannah WJ, Vayda E, Singer J. Opinion leaders vs audit and feedback to implement practice guidelines. Delivery after previous cesarean section. JAMA. 1991 May 1;265(17):2202–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaillet N, Dube E, Dugas M, Audibert F, Tourigny C, Fraser WD, et al. Evidence-based strategies for implementing guidelines in obstetrics: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Nov;108(5):1234–45. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000236434.74160.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A. Translating guidelines into practice. A systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Cmaj. 1997 Aug 15;157(4):408–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimshaw J, McAuley LM, Bero LA, Grilli R, Oxman AD, Ramsay C, et al. Systematic reviews of the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies and programmes. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003 Aug;12(4):298–303. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.4.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. 2. San Francisco: Berett-Koehler; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomized trials in health research. London: Arnold; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, SL Z. Analysis of longitudinal Data. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omar RZ, Thompson SG. Analysis of a cluster randomized trial with binary outcome data using a multi-level model. Stat Med. 2000 Oct 15;19(19):2675–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2675::aid-sim556>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reading R, Harvey I, McLean M. Cluster randomised trials in maternal and child health: implications for power and sample size. Arch Dis Child. 2000 Jan;82(1):79–83. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199(2):133, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph KS, Rouleau J, Kramer MS, Young DC, Liston RM, Baskett TF. Investigation of an increase in postpartum haemorrhage in Canada. BJOG. 2007 Jun;114(6):751–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron CA, Roberts CL, Olive EC, Ford JB, Fischer WE. Trends in postpartum haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006 Apr;30(2):151–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)? Evidence for a “trial effect”. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001 Mar;54(3):217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caliskan E, Dilbaz B, Meydanli MM, Ozturk N, Narin MA, Haberal A. Oral misoprostol for the third stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101(5 Pt 1):921–8. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200305000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]