Abstract

Several studies have explored differences between North American and European doctor-patient relationships. They have focused primarily on differences in philosophical traditions and historic and socio-economic factors between these two regions that might lead to differences in behaviour, as well as divergent concepts in and justifications of medical practice. However, few empirical intercultural studies have been carried out to identify in practice these cultural differences. This lack of standard comparative empirical studies led us to compare differences between France and the USA regarding end-of-life decision making. We tested certain assertions put forward by bioethicists concerning the impact of culture on the acceptance of advance directives in such decisions. In particular, we compared North American and French intensive care professional’s attitudes toward: 1) advance directives and 2) the role of the family in decisions to withhold or withdraw life-support.

Keywords: advance directives, family, cross-cultural comparison, decision making, intensive care

Introduction

Cross-cultural analyses comparing the North American bioethical model to the Latin model of Southern Europe typically characterize the North American model as liberal and individualistic and the Southern European model as being a more socially oriented and responding to the norms of professional deontology.1 In the American system, on this view, the moral obligations of doctors are derived from the so-called “negative” rights of individual patients, which are based first and foremost on a respect for individual liberty. These rights ensure the non-intervention of other individuals — particularly doctors and close relatives of the patients — or of the State in the private life of patients.2 In the USA, informed consent and advance directives (AD’s) –in cases where the patient is no longer able to make decisions- are seen as the principal means for ensuring that these rights are respected. As in other liberal societies, the ability to give consent in the USA is paramount and the State cannot take the place of the individual. In Latin societies, such as France, individual consent is recognised, but is sometimes tempered by the intervention of professionals, close relatives and the State, who can modify individual choice for the good of the person, in the name of a collective rule.3

According to some,4,5 the paternalism of French healthcare professionals is much more complex and justifiable than a simple desire for power. For example, F. Pochard et al. suggest that this paternalism in intensive care is not an authoritarian desire of power by doctors, but instead reflects an acceptance of responsibility for decisions accorded to doctors by patients and their close relatives. They suggest in particular that patients “may prefer to relinquish autonomy in situations they feel are overwhelmingly painful or guilt-ridden”(p.1890).5 Our study compares the attitudes of French and American intensivists toward AD’s and the role of family so that differences can be better understood while avoiding mere cultural prejudice.

Health and legislative context of advance directives in the us and france

In France and the US, death is increasingly likely to occur in hospitals,6–8 frequently as a result of the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining treatments,9,10 Despite growing consensus on the importance of seeking and respecting the opinions of the patient at the end of life, several factors — including the unconscious state of most patients hospitalised in emergency and intensive care units (ICUs), and the close relatives being unaware of the patients’ wishes — may prevent the patient’s wishes being taken into account.11,12

AD’s were first developed in the United States towards the end of the 1960s, to allow the opinion of the patients to be included in the decision-making process at the end of life.13 Since 1990, the Patient Self Determination Act makes it obligatory to provide the patient with information about AD’s as soon as he or she is admitted to any US hospital receiving federal funds. This act also obliges healthcare professionals to check carefully whether or not their unconscious patients have such written documents and to indicate their presence or absence in the medical chart.14 In France, AD’s were provided a legal basis only in 2005 through the law n° 2005-370 related to the patient’s rights and the end-of-life. This law established, for the first time in France, an obligation for doctors to take into account the wishes of the patient expressed in an AD concerning the withholding or withdrawing of life support.15

Objectives and hypotheses

We explored the acceptance of AD’s by healthcare professionals in France and the US. We also tested the hypothesis that the decision to withdraw or withhold life-sustaining treatment is more dependent on the patient’s wishes and less dependent on families’ wishes in the USA than in France.

Methods

Three different clinical scenarios corresponding to incompetent patients having expressed, through an AD, a refusal to receive vital treatment were presented, during individual interviews, to 66 health professionals. In April 2003, 36 professionals belonging to three ICUs from Parisian hospitals were interviewed.A One year later, we carried out similar interviews with 30 intensivists working in two ICUs in Ohio. Only the professionals in each department likely to take part in end-of-life decision-making (doctors, nurses and interns) were interviewed.

The scenarios correspond to typical situations and shed light on a heterogeneous group of decision-making issues that have been discussed in bioethical and medical papers15–18. These scenarios differ in their circumstances (i.e. patient diagnosis, prognosis and age, and the patient’s reasons for writing an AD), but all have one thing in common: respect of the patient’s wishes would inevitably lead to the patient’s death.

Case 1 concerns a 40-year-old patient in a vegetative state since a road accident six months previously. In his AD, this patient refused to accept the parenteral nutrition and hydration currently keeping him alive. The work of the Multi-Society Task Force on PVS has shown that a patient in this state no longer has the mental capacity to be conscious of himself or of his environment. He has a 46% chance of “coming round” (awake with reactions to visual and auditory stimuli) and a less than 0.5% chance of recuperating his functions (communication, ability to learn, ability to adapt, mobility, ability to take care of himself and to take part in recreational activities). Furthermore, having shown no improvement in the previous three months, this patient has a significantly reduced chance of displaying functional improvement with no associated severe sequelae.19

Case 2 concerns a 70-year-old patient who has suffered a minor cardiac event and who also suffers from Alzheimer’s disease, making it impossible to obtain informed consent. Apart from this acute episode, he clearly still has a certain quality of life. His life expectancy, if he overcomes the cardiac problem, may be several years, during which time his state of health will gradually worsen, due to his underlying degenerative disease. Prior to losing his mental capacity and while still fully competent, the patient signed an advance directive in case of his becoming incompetent and suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease. In this document he declared that he did not want to have his life artificially prolonged if he became incapable of living his current standard of life.

Case 3 concerns a 39-year-old patient with no significant medical history. He requires a transfusion, but his life is not immediately in danger. He is mentally capable and refuses blood products due to his religious beliefs, claiming to be a Jehovah’s Witness. He has asked that all other treatments be tried to cure him. However, his situation deteriorates; he loses consciousness and a transfusion becomes absolutely necessary to save his life.

We asked them whether they would follow the AD’s in two different situations: 1) in which the close relatives wanted to follow the AD of the patient, and 2) in which the close relatives opposed the AD of the patient.

We asked health professionals to respond according to their own convictions and to not take into account any eventual legal consequences that could affect their decisions, so as to collect opinions as independent as possible from the legal context in each country.B Three responses were possible for each situation: “I would follow the advance directives”; “I would not follow the advance directives”; and “No definitive opinion”.

For American health professionals, the script for the interview was translated by an American translator and validated by an American intensivist. The results were analysed by the group of researchers who designed the interview, together with two other external people competent in medical bioethics — one French, one American.

In US, the protocol was approved by the ethics commitee of MetroHealth System, Cleveland (Ohio). In France, ethics commitee approval for this kind of sociological research using professionals as research subjects is not required.

Results

The two groups were homogeneous for the number of professionals, mean age, sex, post held and number of years of experience in the ICU. We found no statistical link between these variables and the responses of the professionals. We found a significant difference between French and American professionals in terms of the distribution of religious beliefs: the numbers of religious and non-religious professionals were similar in France, whereas there were more religious than non-religious American professionals (Table 1). Compared to France, US professional’s religious affiliation was more diversified. In France we found a significant number of professionals who considered themselves religious but who did not have or disclose a particular affiliation (Table 2).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic data

| Nationality | French (%) | American | Total (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 36 | (%) N = 30 | N = 66 | |||

| Age (average) | 32.1 | 30.6 | |||

| Sex | Female | 53 | 73 | 62 | 0.086 |

| Male | 47 | 27 | 38 | ||

| Experience | < 3 years | 61 | 43 | 53 | 0.150 |

| > 3 years | 39 | 57 | 47 | ||

| Profession | Doctor | 53 | 30 | 42 | 0.062 |

| Nurse | 47 | 70 | 58 | ||

| Religion | Religious | 53 | 73 | 62 | 0.033* |

| Non religious | 47 | 27 | 38 | ||

p < 0.05

Table 2.

religious affiliation of professionals by country

| Affiliation | Catholic | Christian | Protestant | Islam | Baptist | No affiliation | No religion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French (n)* | 11 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 18 |

| American (n) | 15 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | - | 7 |

One French professional didn’t answer this question

Respect for Advance Directives in each country

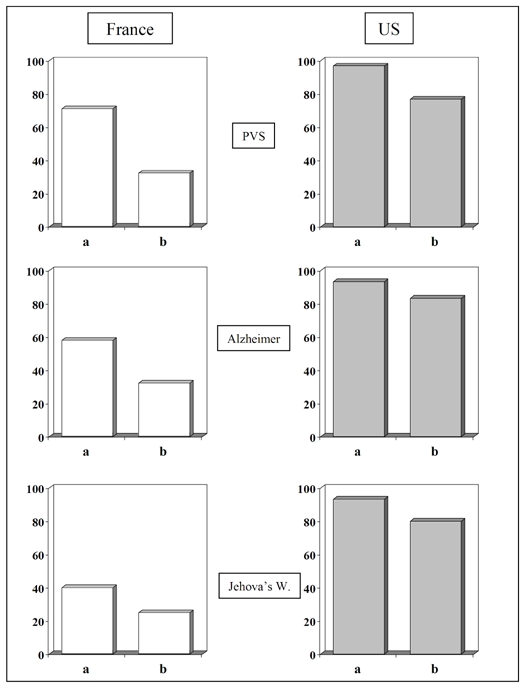

For the patient in a vegetative state (case 1), provided that the family agreed to follow the will of the patient, we found no significant difference between the attitudes of the French and American professionals. However, we found a very significant difference between the two nationalities if the family opposed the wishes of the patient: most of the Americans followed the wishes of the patient, whereas most of the French did not. For the other two cases — patient with Alzheimer’s disease (case 2), and the Jehovah’s Witness (case 3) —French professionals were less likely to follow the AD’s than the American professionals, whether or not the relatives agreed with the AD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Responses of the French and American professionals

| Attitude of close relatives | Country | Would follow the AD | Would not follow the AD | No definitive opinion) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (% | |||

| PVS | Agreed | FR | 22 (71) | 3 (10) | 6 (19) |

| USA | 29 (97) | 1 (3) | - | ||

| Opposed | FR | 10 (32) | 18 (58) | 3 (10) | |

| USA | 23 (77) | 4 (13) | 3 (10) | ||

| Alzheimer | Agreed | FR | 18 (58) | 7 (23) | 6 (19) |

| USA | 28 (93) | 2 (7) | - | ||

| Opposed | FR | 10 (32) | 15 (48) | 6 (19) | |

| USA | 25 (83) | 4 (13) | 1 (3) | ||

| Jehova’s Wit. | Agreed | FR | 14 (40) | 18 (51) | 3 (9) |

| USA | 28 (93) | - | 2 (7) | ||

| Opposed | FR | 8 (23) | 22 (65) | 4 (12) | |

| USA | 24 (80) | 4 (13) | 2 (7) | ||

When the families were opposed to the AD, more than half the French intensivists respected the opinion of the family rather than that of the patient in cases 1 and 3, and almost half respected the opinion of the family rather than that of the patient in case 2. French professionals were least likely to follow the AD for the Jehovah’s Witness. The American professionals made less distinction between the three cases, and mostly followed the wishes of the patient. They appeared less likely to the AD’s of the patient if opposed by the family, but the difference between these two situations was not statistically significant.

Generally, we found that the French professionals were less likely to respect the AD’s and were more likely to have no definitive opinion than the American professionals. This difference increased if the family opposed to the will of the patient, in all three cases. French professionals were found to be, on average, 2.4 times more likely to change their attitude than the American professionals in the face of family opposition to the AD (Table 4 and Figure).

Table 4.

Influence of the opinion of the family on the response of each group

| Country | Change attitude | No change in attitude | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | RR(*) | N | RR(**) | ||

| PVS | FRANCE | 17 | 2.71 | 14 | 1.77 |

| USA | 6 | 24 | |||

| Alzheimer | FRANCE | 10 | 3.23 | 21 | 1.32 |

| USA | 3 | 27 | |||

| Jehova’s Wit. | FRANCE | 8 | 1.37 | 27 | 1.08 |

| USA | 5 | 25 | |||

RR = relative risk: expressed as the number of times the French would change attitude with respect to the Americans.

RR = relative risk: expressed as the number of times the Americans would not change attitude with respect to the French.

Figure.

Percentage of professionals in each country following the AD’s in the three cases: agreement of the family (a); opposed by family (b).

Discussion

Methodological limits

Our study has several limitations requiring consideration before any analysis of the results. First, the study population consisted of 66 professionals from hospitals from geographically limited areas in the two countries (Paris and Cleveland). This makes it difficult to generalise our results. Second, we obtained responses to hypothetical scenarios, which, though they reflect typical cases in important respects, cannot capture the complex medical, emotional, and social realities of actual cases. Third, our study was devised to observe the moral attitudes of the doctor rather than what they would have done to remain within the law in their country: what is morally acceptable is not necessarily legally acceptable and vice versa. By contrast to Ohio, where AD’s were legalised in 1991, AD’s were not legalised in France until the end of our study. We therefore insisted that the professionals responded “according to what they consider morally acceptable, rather than according to what is considered legal”. Thus, we tried to free ourselves of the medical legal context, making it possible to compare attitudes in the context of a situation in which AD’s are legal, irrespective of the actual situation at the time of the study. We have two reasons for believing that respondents answered according to their own moral conception. On the one hand, the interviews were anonymous and the interviewer assured the confidentiality of all personal data. On the other hand, several professionals indeed expressed personal disagreement with the law in their country (or to what they thought to be legal) by saying that they would have answered in a different way if they had taken into account the legal situation. However, since legal frameworks usually influence moral conceptions, we cannot exclude the possibility that the responses of certain professionals were partially based on what they believed was legal. This is, therefore, an acknowledged limitation of the study.

“Culture”, Advance Directives, and the ICU

M.A. Sánchez González offers a possible explanation for the much later development of legislature for AD’s in Southern European than in the US.20 He suggests that the development and success of AD’s in the US is due to several cultural and societal factors specific to it. First, he suggests that the “consumerist” and “entrepreneurial” nature of the American health system as well as the contractual nature of the patient/doctor relationship render healthcare in the US a matter of negotiation between patients and the healthcare staff. AD’s therefore provide means of formalising this quasi-commercial transaction in which “consumers are apt to make their own medical choices and free to select the best goods for the lowest price”(p.288).20 AD’s would not play this role in countries such as France, in which health care is free and supported by the State. Second, the according of priority to autonomy over other principles, such as charity and justice, as well as a “radically individualist” notion of society account for American professionals considering the isolated individual as, according to Sánchez-González, “the only fundamental reality”(p. 291). As a result, the patient’s opinion is of prime importance, and prevails over the opinions of close relatives and public interest. The role played by the patient’s family in decision-making is therefore often different from that played by families in France. In fact, many theoretical studies claim that the opinions of close relatives carry much more weight in Southern European countries than in more liberal countries.1,5,20,21 D. Dickenson considers that, in Great Britain and the Netherlands, “consent from family members cannot override the patient’s own refusal, whereas in most Southern European systems, familial proxy consent is important”(p.253).1 Third, in the US, the “radical” concept of moral pluralism, according to which several concepts of “good” can and must co-exist, would make tolerance of the private life of the individual and his or her personal values an almost absolute obligation. Sánchez González suggested that the absence of these conditions in Mediterranean countries leads to problems in accepting AD’s in medical practice.

Our study can be interpreted as lending credence to some of the views expressed in these cross-cultural analyses where AD’s are concerned. American intensivists are more likely to honour AD’s than French ones. Also, unlike American professionals, most French professionals avoid taking decisions that go against the wishes of the close relatives, even if these professionals themselves initially wanted to follow the wishes of the patient. Thus, French professionals are much more influenced by the familial context and this may be explained by the previously described cultural characteristics of traditional medical practice in Mediterranean countries.

Nonetheless, we found that one in five French professionals for case 3, and one in three for cases 1 and 2 was ready to go against the wishes of the family. Furthermore, more than one in ten American professionals would follow the wishes of the family against those embodied in AD’s. These findings represent considerable variance from standard and perhaps stereotypical cross-cultural views that have dominated bioethics (e.g., French “paternalism” and deference to family wishes and American “radical individualism” and disregard of family wishes) and suggests that French and American ICU professionals do not have attitudes that are as radically different as some have supposed.

Remaining problems with Advance Directives

Even though end-of-life decisions are widespread in intensive care practice in France,22 the opinion of the patient on the desired intensity of treatment or on withholding therapy is unavailable or unknown to the professional in more that 90% of cases.9 In US, the Patient Self Determination Act has led to a significant increase in the percentage of patients writing such documents.23,24 However, based on more that 100 empirical studies evaluating the usefulness of AD’s, Fagerlin and Schneider showed that these documents (and living wills in particular) have not fulfilled all expectations.25 They showed that 1) more than 80% of the American population have never had an AD; 2) some patients had filled out an AD, but not in a way that could be correctly applied by the caregivers; 3) some did not know how to express their wishes or how to write them satisfactorily; 4) some had changed their minds; 5) some had not done enough to make their doctor aware of the existence of such a document; and 6) the AD’s did not provide close relatives with a clearer vision of what the patient would have wanted, or the professionals to adapt their practices better to the wishes of the patient. The authors concluded that the American political encouragement of AD’s has been at too great a cost, with too few results.

Conclusions

The situation in France today with respect to end-of-life practices looks similar to how it looked in the early 1990’s in the US. In the US, AD’s have not been widely adopted despite their legal support and the apparent broad recognition of caregivers that patient’s wishes, as expressed through AD’s, should be respected. In France, the practice of writing AD’s is much more recent and less extended than in US. We found some important but not radical differences between American and French intensive care professionals’ attitudes towards AD’s and the family wishes. Neither French professionals ignore systematically the autonomy of the patient nor the American ones systematically oppose the wishes of the family in order to honour those of patients. Nevertheless, French intensivists clearly afford more weight to family wishes in cases of conflict with patient previous wishes, than do American doctors (at least in hypothetical case responses). That led us to remain sceptical concerning the respect that AD’s will obtain in France, especially when proxies will disagree with them and want to continue undesired or futile life sustaining treatment. Mechanisms for teaching professionals how to prevent or deal with potential conflicts between proxies’ wishes and patient’s interests might be developed, both in France or the US. The deeper issue underlying AD’s whether in the US or France is the moral and political right of patients to direct their health care even when unable to make decisions for themselves. To the extent that this right is to be taken seriously in either context, mechanisms for allowing patients to exert control over decision making must be developed. AD’s are a flawed, but defensible, way of doing this. Although AD’s cannot resolve all problems, they are often informative for end-of-life decision making and, in certain very problematic cases, the only means by which the best interests of patients who are no longer able to communicate can be decided. Perhaps other more culturally tailored approaches might be more effective. More comparative empirical research is needed in order to reach a deeper understanding of the simmilarities and diversities between North American and European models of patient-proxy-professional relationship.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the help of James Lovette, Dawn Alpaugh, Joel R. Peerless, Ana Villar, Jean Carlet, Edouard Ferrand, Jean Roger Legall, and José María García Gómez-Heras. This research received the financial aid from “La Caixa” Foundation and the “International Institute of Research in Ethics and Biomedicine”.

Footnotes

The qualitative and quantitative results of this work can be found in http://infodoc.inserm.fr/inserm/ethique.nsf/ViewAllDocumentsByUNID/0F0F9626715021B2C12570A50051515B/$File/DEA+Rodr%EDguez-Arias.pdf?OpenElement

When the interviews were carried out in France, the law on advance directives had not yet been adopted. In reality, the withdrawal and withholding of vital treatment were not legally different from euthanasia (this situation changed in April 2005). In practice, the decision to withhold and withdraw treatment had for several years been a frequent occurrence in intensive care units9. The absence of a law made these practices clandestine during these years and, in many case, the healthcare professionals concerned left no trace in the medical files of having made these decisions5.

References

- 1.Dickenson DL. Cross-cultural issues in European bioethics. Bioethics. 1999;13(3–4):249–55. doi: 10.1111/1467-8519.00153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gracia D. The intellectual basis of bioethics in Southern European countries. Bioethics. 1993;7(2–3):97–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.1993.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moutel G. Le consentement dans les pratiques de soins et de recherche en médecine. Paris: l’Harmattan; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard MS. Soigner la relation malade-famille-soignants. La Plaine Saint Denis: Centre de Recherche et de Formation sur l’Accompagnement de la Fin de Vie; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. French intensivists do not apply American recommendations regarding decisions to forgo life-sustaining therapy. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(10):1887–92. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CCNE. Rapport n° 63: Fin de vie, arrêt de vie, euthanasie. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decisions near the end of life. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA. 1992;267(16):2229–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Risks and Outcomes of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(10):1242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrand E, Robert R, Ingrand P, Lemaire F. Withholding and withdrawal of life support in intensive-care units in France: a prospective survey. French LATAREA Group. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eidelman LA, Jakobson DJ, Worner TM, Pizov R, Geber D, Sprung CL. End-of-life intensive care unit decisions, communication, and documentation: an evaluation of physician training. J Crit Care. 2003;18(1):11–6. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2003.YJCRC3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrand E, Bachoud-Levi AC, Rodrigues M, Maggiore S, Brun-Buisson C, Lemaire F. Decision-making capacity and surrogate designation in French ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(8):1360–4. doi: 10.1007/s001340100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanson LC, Danis M, Mutran E, Keenan NL. Impact of patient incompetence on decisions to use or withhold life-sustaining treatment. Am J Med. 1994;97(3):235–41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law Journal. 1969;44:539–554. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patient self-determination act, US. 1990. www.dgcenter.org/acp/pdf/psda.pdf.

- 15.Assemblée Nationale. Code de Santé Publique; Loi n° 2005–370 du 22 avril 2005 relative aux droits des malades et à la fin de vie, art 10 I; p. Article L1111–11. www.assembleenationale.fr/12/dossiers/accompagnement_fin_vie.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mappes TA. Persistent vegetative state, prospective thinking, and advance directives. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2003;13(2):119–39. doi: 10.1353/ken.2003.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dresser R. Dworkin on dementia. Elegant theory, questionable policy. Hastings Cent Rep. 1995;25(6):32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kleinman I. Written advance directives refusing blood transfusion: ethical and legal considerations. Am J Med. 1994;96(6):563–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Multi-Society Task Force on PVS. Medical aspects of the persistent vegetative state (2) N Engl J Med. 1994;330(22):1572–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406023302206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez-Gonzalez MA. Advance directives outside the USA: are they the best solution everywhere? Theor Med. 1997;18(3):283–301. doi: 10.1023/a:1005765528043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortina A. ¿Existe una bioética latina? In: López de la Vieja M, editor. Bioética Entre la medicina y la ética. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca; 2005. pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Hennezel M. Mission parlementaire « Fin de vie et accompagnement » Rapport remis à Monsieur Jean-François Mattéi. Ministre de la Santé, de la Famille et des Personnes Handicapées; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley EH, Wetle T, Horwitz SM. The patient self-determination act and advance directive completion in nursing homes. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(5):417–23. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terry M, Zweig S. Prevalence of advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders in community nursing facilities. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3(2):141–5. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.2.141. discussion 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]