SUMMARY

Where very young children come into contact with water containing schistosome cercariae, infections occur and schistosomiasis can be found. In high transmission environments, where mothers daily bathe their children with environmentally drawn water, many infants and preschool-aged children have schistosomiasis. This ‘new’ burden, inclusive of co-infections with Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni, is being formally explored as infected children are not presently targeted to receive praziquantel (PZQ) within current preventive chemotherapy campaigns. Thus an important PZQ treatment gap exists whereby infected children might wait up to 4–5 years before receiving first treatment in school. International treatment guidelines, set within national treatment platforms, are presently being modified to provide earlier access to medication(s). Although detailed pharmacokinetic studies are needed, to facilitate pragmatic dosing in the field, an extended ‘dose pole’ has been devised and epidemiological monitoring has shown that administration of PZQ (40 mg/kg), in either crushed tablet or liquid suspension, is both safe and effective in this younger age-class; drug efficacy, however, against S. mansoni appears to diminish after repeated rounds of treatment. Thus use of PZQ should be combined with appropriate health education/water hygiene improvements for both child and mother to bring forth a more enduring solution.

Key words: Maternal and child health, preventive chemotherapy, dose pole, morbidity markers, faecal occult blood, GPS dataloggers

INTRODUCTION

In this review we outline past progress, current evidence and new steps taken to control schistosomiasis in African infants and preschool-aged children (PSAC). This evolving situation is set within the context of preventive chemotherapy campaigns which, during the last decade, have progressively scaled-up operations to reach nationwide coverage in several sub-Saharan countries (Savioli et al. 2009; WHO, 2010). We also present some key epidemiological findings from an ongoing prospective cohort study of Ugandan children who have intestinal schistosomiasis and are regularly receiving praziquantel (PZQ) treatment(s).

Schistosomiasis and children

Control interventions targeted towards schistosomiasis, as presently recommended by WHO, have primary focus upon provision of free treatment with PZQ to school-aged children (SAC), 5–14 years old, as well as, adults (⩾15 years old), who reside within disease endemic regions (WHO 2006; Fenwick et al. 2009). Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) activities undertaken to assess performance and impact of such interventions – usually implemented by governmental authorities in the framework of their national disease control programmes (NDCPs) – have shown that over 17 million individuals were treated in 2008 (WHO, 2010), but have also revealed that children aged 5 years and below – preschool-aged children (PSAC, 1–5 years old) and infants (1–12 months old) – can be commonly infected (Bosompem et al. 2004; Odogwu et al. 2006). Moreover, many are at clear risk of developing overt disease and sadly these children are almost invariably overlooked within treatment campaigns. Therefore for some, their disease-related morbidity and discomfort has not been averted as quickly nor as successfully as possible.

REDISCOVERY OF SCHISTOSOMIASIS IN YOUNG CHILDREN

A singular and incomplete literature

It's an old explorer's adage that you only find what you are looking for and that, without considerable pre-planning, ‘discoveries’ are not always as serendipitous as they first seem. In the context of assessing the occurrence and importance of schistosomiasis in the younger child, whilst infections in infants and PSAC had been noticed a long time ago (Smith, 1958; Perel et al. 1985), it firmly fell off the radar of the medical and scientific community as a topic of public health importance until only recently. This was due to a largely disjointed literature which was a collection of sporadic reports failing to synergise as a whole and promote the consequence of infections at an early age (Woolhouse et al. 2000). It was noted, however, that ‘hyper-infections’ were possible causing the singular death of a Brazilian PSAC where thousands of adult worms were recovered at autopsy (Gryseels and de Vlas, 1996).

Later, as the diagnostic methods then available failed to find egg-patent infections and field epidemiological studies reported that active water contact rates, i.e. swimming and direct playing in water, were generally low, it became widely believed that infections were very rare in this younger age-class (Jordan and Webbe, 1969). Furthermore, this apparent lack of exposure became a pervasive argument, sufficient to result in categorisation of infants and PSAC as largely free from disease unless infection was taking place ‘in their back yard’ (Jordan and Webbe, 1969). During this period, general interest rightly focused upon devising urgent strategies to combat schistosomiasis in SAC and adolescents, where it was becoming apparent that in many places across sub-Saharan Africa, infections were almost universal (Engels et al. 2002; Bergquist, 2008).

From a research perspective, this aspect of disease in young children was further subsumed by the general focus upon schistosome-immunology and vaccine development (Colley and Secor, 2007; Bethony and Loukas, 2008), as well as the growing excitement in exploring the parasite's genome with new molecular tools, which has started to come to fruition (Webster et al. 2010). From a control perspective, there were many changes too; with the more affordable price of PZQ as a public health tool (Fenwick et al. 2003), international advocacy grew (Hotez et al. 2007) and secured new financial support culminating in the release of major donor funds which fostered the start-up and roll-out of several NDCPs administering PZQ in preventive chemotherapy, then later in integrated preventive chemotherapy for neglected tropical diseases, to as many SAC and adults as possible (Hotez et al. 2007; Fenwick et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2010).

A fresh focus on the younger child

The realisation that infection and disease were occurring in children younger than school age started to take form during discussions in London in May 2003, during the first annual Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) review meeting. There, it became apparent that especially poor sanitation and water-hygiene conditions abounded in several SCI-supported countries, as exemplified by images and video footage within the “SCI Advocacy for Control in Uganda” video and health CD (Beanland et al. 2006). The film typified the remote and rural conditions of high-transmission environments along shoreline villages of lakes Albert and Victoria, Uganda.

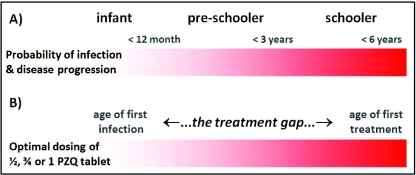

During this meeting, it was clearly shown that infants and PSAC were being regularly bathed with freshly drawn environmental water, either at the water's source or at home, which unmistakeably pointed towards much more substantive levels of water contact and exposure than previously thought. This was also in accordance with the remarkably high levels of disease prevalence (>75%) in schoolchildren attending reception class (between 5–7 years old) in Ugandan primary schools (Kabatereine et al. 2007), which made it clear that a likely ‘PZQ treatment gap’ was occurring in PSAC, as conceptualised in the schematic of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of the ‘PZQ treatment gap’ in young children for schistosomiasis which can typically be between 1 and 4 years. The red bar gradient depicts a possible timeline of duration of infection and disease progression (A) and the open question of when a child should receive first treatment within this timeline is raised (B). Upon entry into the primary school system, children aged 5–6 years usually receive first treatment of 1 tablet of PZQ (i.e. 40 mg/kg dose) although much younger children are known to be infected before entry into formal schooling. Indeed, the age of first infection can be within the first year and for some the ‘PZQ treatment gap’ may be up to 5 years in duration.

This supposition of a treatment gap occurring was later confirmed by ad hoc epidemiological surveys of PSAC in Uganda and Ghana using more sensitive diagnostic methods (Bosompem et al. 2004; Odogwu et al. 2006).

DEFINING THE ‘PZQ TREATMENT GAP’

Building a new epidemiological synthesis

The evidence provided by Bosompem et al. (2004) and Odogwu et al. (2006) clearly showed that children under 3 years of age were at substantial risk of urinary or intestinal schistosomiasis, with a surprisingly large proportion already having egg-patent infections. Moreover, these infections were most likely not acquired by active water contact of the child but rather by passive exposure(s) to water containing schistosome cercariae owing to the bathing and water-drawing practices of their mothers/guardians. This was clearly affirmed by Odogwu et al. (2006) who interviewed mothers of the children with a semi-structured water contact questionnaire.

Attempting to draw a new epidemiological appraisal, the article by Stothard and Gabrielli (2007a) was the first provocative attempt to highlight the importance of schistosomiasis in the younger child and this ‘PZQ treatment gap’, set within the context of preventive chemotherapy and NDCPs. It reported on the present inequality of health care provision and outlined some steps that needed to be undertaken to move towards inclusion of younger children within disease control strategies. Foremost was to foster inter-sectoral collaborations with other stakeholders committed to maternal and child health. The article stimulated some debate and points raised by Johansen et al. (2007) were formally discussed by in a reply by Stothard and Gabrielli (2007a). The conclusion drawn was that formal inclusion of younger children in treatment campaigns was warranted, along with further thematic research necessary to optimise interventions and ensure safety (Johansen et al. 2007; Stothard and Gabrielli, 2007a, b).

There have been several other reports investigating the occurrence of schistosomiasis in younger children across sub-Saharan Africa (Mafiana et al. 2003; Opara et al. 2007; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2008; Stothard et al. 2008; LaBeaud et al. 2009; Chu et al. 2010; Ekpo et al. 2010; Garba et al. 2010; Dabo et al. 2011; Namwanje et al. 2011; Verani et al. 2011). A particularly disturbing report of which is by Garba et al. (2010) documenting that S. haematobium and S. mansoni co-infections are common among very young children in Niger. Alarmingly, in certain mixed-species transmission foci in Mali, for example, very young children have overt morbidity of the bladder, ureters and kidneys as detectable upon ultrasonography (M. Sacko, unpublished data). These observations on co-infection clearly open up another avenue of research detailing how young children respond to each parasite separately, or in combination, potentially revealing any interactions through time. Such early infections are also likely of consequence in modulating response to routine vaccination (LaBeaud et al. 2009).

The importance of early treatment with PZQ

Schistosomiasis in infants and PSAC is of concern for at least two reasons. First, this younger age-group plays a hitherto unrealised role in helping to maintain local disease transmission; even though these infected children may be excreting fewer eggs, it is their regular water contact that leads to contamination of water. Moreover, rinsing and washing children's soiled clothes in environmental water bodies also contributes towards more cryptic contamination and disease transmission (Stothard and Gabrielli, 2007a). Thus this age-group might well play an increasingly important role in environmental transmission likely to frustrate the attempts made by preventive chemotherapy campaigns striving towards more general reductions in environmental transmission (King et al. 2006; French et al. 2010). Second, such regular water contact is also likely to result in frequent (re)infection episodes, which lead to a progressive increase of individual worm burden. It is therefore likely that untreated infections acquired in early childhood contribute to worsening the longer-term clinical picture of disease in the individual (Stothard et al. 2011a).

Both reasons call for a more inclusive approach to control of schistosomiasis. Of note is an additional consideration that younger children, being smaller, will require fewer tablets of PZQ than their older counter-parts, and therefore treatment initiatives targeting the younger child could be cheaper, in terms of drug procurement, and achieve promising future returns in reduction of both morbidity and transmission (Hotez et al. 2010; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010a).

ADMINISTRATION OF PZQ IN THE YOUNGER CHILD

Problems in the administration of PZQ to very young children became evident in the context of a pilot programme targeting the under-fives in Ugandan shoreline villages of lakes Albert and Victoria conducted in 2006 (Stothard et al. 2008) and 2009 as reported by Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (2010b). The rationale of this intervention was that parasitological surveys using more sensitive diagnostic techniques of worm-antigen and host-antibody detection, had revealed the common occurrence of schistosomiasis infection and disease in infants and PSAC living in this area. This was further evidence of this age-class was playing a stable role in endemic disease transmission. Thus it was deemed necessary to expand the NDCP's treatment remit in these areas, even in the absence of pharmacokinetic evidence, and provide these infected children with treatment as not to do so was considered unethical (Johansen et al. 2007).

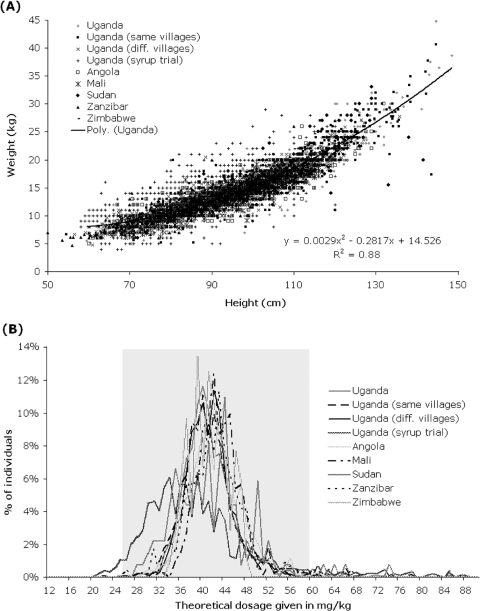

An extended PZQ ‘dose pole’

As these shoreline environments are typical resource-poor settings, the availability of reliable weighing scales was constrained and a limiting factor in a public health setting (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b). Therefore, a PZQ ‘dose pole’ was needed similar to that used in treatment of SAC (Montresor et al. 2001, 2002). However, the existing WHO height pole's lowest height division is 94 cm (above which a single 600 mg-tablet is recommended) and this lower threshold was too-high to cover the typical stature range of infants and PSAC. An extended pole was therefore developed based upon height and weight data from several hundred Ugandan children (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b). This formative data set was later added to with additional child height-weight (n=2183) information obtained from elsewhere (Angola, Mali, Sudan and Zimbabwe) permitting an experimental validation of this extended ‘dose pole’ in locations outside Uganda (see Table 1; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b).

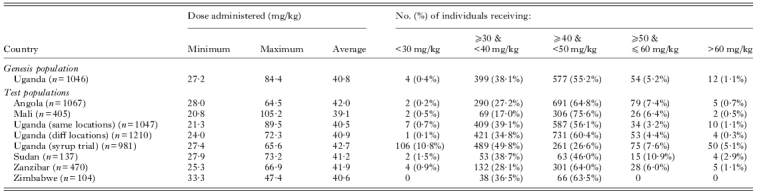

Table 1.

Performance of the extended dose pole in estimating PZQ dosages in children aged ⩽6 years. A PZQ optimal dose was defined as being between 40 and 60 mg/kg and an acceptable dose as being between 30–60 mg/kg

Note: all height and weight data collected to the nearest 0·1 kg and 0·1 cm, respectively except for Sudan and Angola (0·5 kg and 0·5 cm) and Uganda – syrup trial (1 kg and 1 cm).

In amending the PZQ dose pole, two new height intervals were added at the bottom to extend the PZQ treatment pole downwards: 84–99 cm for three-quarters tablet and 60–84 cm for one-half tablet (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b). Based on statistical analysis, the current WHO pole's single table lower limit threshold was upwardly adjusted to 99 cm from 94 cm which facilitated better dosing in this height-weight range. This extended PZQ ‘dose pole’ was initially proven satisfactory in Uganda as well as experimentally on a population of children from Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania (prevalence levels of acceptable dosages, between 30–60 mg/kg, estimated were 98·6% and 97·6%, respectively). The later cross-country evaluation confirmed a broader applicability of this extended ‘dose pole’ (see Table 1). Visual inspection of Fig. 2B reveals that its performance is acceptable in providing 30–60 mg/kg dose of PZQ in the sampled population.

Fig. 2.

Creating and applying the newly extended PZQ ‘dose pole’ for more rapid dosing of PSAC (1–4 year olds) with the distribution of height and weight measurements from children from: Uganda – ‘genesis’ population n=1046, ‘same villages’ population n=1047, ‘different villages’ population n=1210, ‘syrup trial’ population n=981; Angola (n=1067); Mali (n=405); Sudan (n=137); Zanzibar (n=470) and Zimbabwe (n=104) with a polynomial model was fitted to validate information for ‘genesis’ population (A). The distribution of PZQ dosages that would have been given to Ugandan, Malian, Sudanese, Zanzibari and Zimbabwean children if height had been used to predict weight from this extended ‘dose pole’ (B). Grey transparent rectangle highlights the range of children who would have received an acceptable PZQ dose (30 to 60 mg/kg) (see Montresor et al. 2005). Some of these data have been presented elsewhere (see Fig. 3A & B of Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (2010b)).

Concerning the height-weight data collected during a trial of PZQ syrup in Uganda (Table 1) with the aim of assessing the feasibility of provision of liquid formulation of PZQ, it is interesting to note that a poorly serviced set of weighing scales from a local health centre was used for dosing rather than the extended ‘dose pole’. It is clear that the use of these scales generated more severe errors in dosing than the extended dose pole would have introduced. As dose poles are fixed in length and largely immutable, they are much less likely to suffer from such subsequent systematic bias. The unreliability of weighing scales when kept in such resource-poor settings, their potential for de-calibration or malfunction, as well as, the longer time taken to weigh a child (often in conjunction with the mother/guardian holding) suggest that this dosing approach is not pragmatic enough for preventive chemotherapy campaigns. By contrast, ‘dose poles’ offer a more appropriate approach especially when large numbers of children are to be targeted (Montresor et al. 2001, 2002; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010a).

PZQ formulations: crushed tablets or liquid suspensions?

Owing to concerns in using PZQ in children younger than school age (Johansen et al. 2007; Stothard and Gabrielli, 2007a, b), even though the safety and tolerance of this drug in older children is excellent (Utzinger and Keiser, 2004; Doenhoff et al. 2009), Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (2010b) documented more formally the operational conditions and concerns of preventive chemotherapy with PZQ in this resource-poor setting. Given the difficulties of younger children swallowing large PZQ tablets, and an associated risk of choking, medications were administered in crushed tablet form and mixed with orange-syrup as previously piloted by Odogwu et al. (2006). The latter fruit flavour helped to mask the bitter taste of PZQ (Meyer et al. 2009), although some children fail to recognize the unusual taste of PZQ, thus the suspension could be spoon-fed to the child by its mother under supervision of an attending nurse, without any rejection or rarely with complication (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b).

In addition, as post-treatment side-effects of PZQ in SAC are known (Utzinger and Keiser, 2004; Doenhoff et al. 2009) and that as PZQ was being used in an off-label use in this setting, Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (2010b) monitored the occurrence of putative side-effects and efficacy of crushed tablet PZQ treatment. Adverse events and putative side-effects were ascertained by interviewing the mothers (they themselves were treated during the surveys) who then also monitored the welfare of their children at home. Children were then re-examined the following day after treatment along with their mothers attending. Side-effects were mild in nature, e.g. vomiting, fatigue, vertigo and abdominal cramps, and typically resolved by 24 hours after treatment.

As an additional observation, Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (2010b) further monitored a selection of children in a pilot study 21 days after first treatment finding that reported symptoms had reverted to levels at baseline. At this 21-day inspection in villages on the shoreline of Lake Victoria, the parasitological cure rate of 28 previously egg-patent children was found to be 100% (see Table 2). This was initial evidence that the concerns of poor parasitological and pharmacological performance of PZQ within this age class were unfounded.

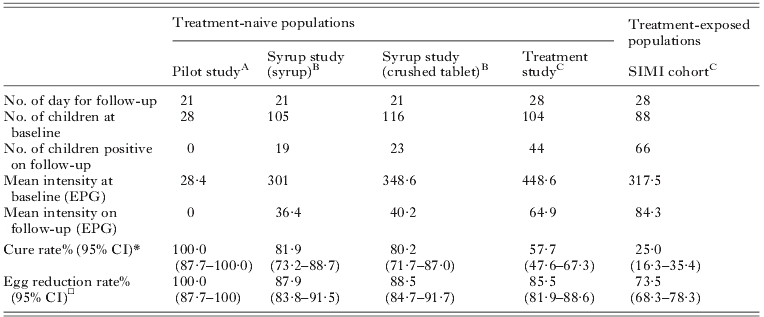

Table 2.

A comparison of the performance of PZQ, in either crushed tablet or syrup suspension, for the treatment of intestinal schistosomiasis in Ugandan children aged ⩽6 years and also against those who were either treatment-naive or a prior treatment history of up to three times during the previous year. Diagnosis of infection status was by duplicate smear Kato-Katz technique on two consecutive day stools on first day of the treatment comparison then at 21 or 28-days later

This took place in Lake Victoria villages in February 2008;

These studies took place in Lake Albert villages in July 2010;

These studies took place in different Lake Albert villages in July 2010 to B;

Cure rate is defined as the percentage of the infected population negative for infection after drug treatment;

Egg reduction rate is defined as the percentage reduction in faecal EPG infection intensity as measured after treatment follow-up.

With increasing interest in whether PSAC should be provided with access to PZQ, in 2010, WHO commissioned a cross-country study (see Mutapi et al. 2011) in the use of liquid suspension, or syrup formulation of PZQ as an alternative to use of crushed or broken tablets. It should be noted that the ‘syrup’ formulation, however, does not mask the bitter taste of PZQ. The results of this treatment comparison in terms of parasitological performance are shown in Table 2, with broader findings to be published elsewhere. In total, over 100 children in each treatment arm (syrup (n=105) versus crushed tablets (n=116)) were examined to find that the formulations were broadly equivalent in terms of cure rates, egg reduction rates and recorded side-effects (data not shown) as reported in Table 2. It is interesting to note that the cure rate in this Lake Albert setting was lower that that previously found in Lake Victoria.

Overall, crushed tablets provide a more pragmatic alternative as tablets are more widely available within sub-Saharan Africa than syrup-based formulations. Moreover, owing to costs of transportation and logistics, syrup-based formulation of paediatric drugs are being advocated less and less by WHO, which is now broadly favouring medications in dispersible tablet formulation which are, however, presently not available for PZQ (L. Chitsulo, personal communication). This is also important for keeping the costs of drug-shipping and distribution as streamlined as possible. Crushed or broken tablets provide an immediate way forward but as a desirable refinement, future PZQ tablets should be manufactured with markings to allow easier division into four quarters than the present half tablet divisions. This is particularly important for more precise dose estimation when treating children weighing between 7·5 and 11·25 kg who need a three-quarters tablet. Looking further into the future, attempts of making PZQ more palatable, i.e. exclusion of the inactive isomer that gives the drug a bitter taste (Utzinger and Keiser, 2004; Meyer et al. 2009; Doenhoff et al. 2009), should be pursued perhaps as well as tablet coatings or linings (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. 2010b).

ONGOING OPERATIONAL RESEARCH IN UGANDA

With funding from the Wellcome Trust, a 4-year project was established in November 2008 with the intention of developing a national treatment platform in Uganda for treatment of infants and PSAC. The project was also to gather new epidemiological information on the performance of PZQ in reducing intestinal schistosomiasis and was set within a prospective cohort study of some 1200 infants and PSAC (Stothard et al. 2011a).

Regular treatment and changes in parasitological efficacy

Until recently, the parasitological performance of PZQ in the younger child was not known, concurrent with the general lack of formal documentation and pharmacokinetics of this drug in its use in infants and PSAC (Stothard and Gabrielli, 2007a, b). More broadly, there are general concerns on the performance of this drug against S. mansoni with reports on occurrence of treatment failures or the necessity of immune-mediated killing mechanisms of adult worms, which is thought to synergise with PZQ-induced damage to the worm tegument (Doenhoff et al. 2009).

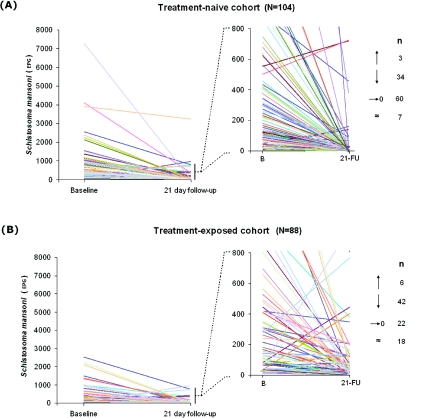

Using new and unpublished information, Table 2 summarises the present knowledge of drug performance within this age-class in Uganda for S. mansoni during these ongoing M&E studies. Overall, the cure rates appear reasonable but of most concern is the lower cure rate of 25% in children with history of previous PZQ treatment over the course of a year. This lower cure rate could simply be the consequence of selection: children who harbour either more PZQ-tolerant worm populations or are only able to mount a partial immune-mediate killing response to adult worms (Doenhoff et al. 2009). The drug clearance curves by individuals are particularly insightful in this light in that there are individuals who do not appear to ‘clear’ infection, or rather, the level of excreted eggs actually increases (Fig. 3). This is especially important in context of stationarity of prevalence of schistosomiasis in the prospective cohort (see below). As a plausible alternative it could also result from subtle adaptive responses of adult worms to become more resilient or repair more quickly the tegumental damage induced by PZQ (Doenhoff et al. 2009). Greater scrutiny of the natural diversity, changes in worm tegument and its dynamic turnover could be particularly insightful in the context of PZQ induced changes.

Fig. 3.

Treatment clearance comparisons between treatment-naive and treatment-exposed preschool-age population cohorts with a graphical representation of individual responses: naïve (n=104) and exposed (n=88), the latter had started to receive treatment in the previous year and at 3 and 6 months prior. Each individual is represented by a line which starts at the individual's initial egg count (eggs per gram of stool – EPG) and ends at their egg count 21 days after treatment. The graph to the right zooms in to the ranges 0 to 800 EPG to give more detail at this finer scale. The numbers to the right indicate the number of individuals whose EPG rose (arrow pointing up), decreased not reaching zero (arrow point down), decreased to zero or cleared (arrow pointing to zero) and those that remained with the same intensity (±24 EPG).

Morbidity markers: faecal calprotectin and occult blood

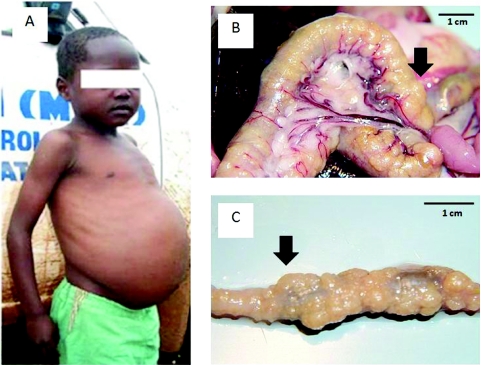

As with general thematic research on schistosomiasis, the search for field-applicable markers of morbidity continues (Webster et al. 2009). In the context of the younger child, this is particularly important as using such markers could help develop a better understanding of an individual's progression from initial infection through to acute or chronic stages of this disease. It would be hoped also that after PZQ medication(s), morbidity will be arrested, with reversion, following from reduction(s) in worm burdens (Betson et al. 2010). It is particularly disappointing that the repertoire of morbidity marker assays is meagre such that whilst SAC can have obvious visual signs of severe disease, for example that the child shown in Fig. 4a who has obvious hepatosplenomegaly and likely has granulomatous masses or ‘bilharzomas’ around the bowel (the latter exemplified in Fig. 4b and 4c within a laboratory animal) it is not possible to document this precisely without recourse to surgery.

Fig. 4.

Image of child with obvious visual signs of intestinal schistosomiasis (A) but likely also has more cryptic bowel pathology which is often not noticed without investigative surgery. To illustrate, in animal models the pathology of the bowel from schistosome granulomas can be extreme as seen in (B) or more so when the intestine is removed (C), the black arrow denotes approximately the same part of the bowel. Not only do such lesions likely lead to malabsorption but also lack of peristalsis. Infection in infancy and early childhood likely leads to development of serious disease even before adolescence.

In search of new markers of bowel morbidity, Betson et al. (2010) determined whether faecal calprotectin or faecal occult blood (FOB) assays could be used as morbidity indicators for intestinal schistosomiasis. They examined a cohort of 1327 PSAC and 726 mothers in Uganda in which the prevalence of egg-patent infection was 27·2% in children and 47·6% in mothers. No association was found between infection and faecal calprotectin in children (odds ratio (OR)=1·08; P=0·881), however, an inverse relationship (OR=0·17; P=0·043) was found in mothers. By contrast FOB was strongly associated with S. mansoni infection in both children (OR=2·30; P<0·001) and mothers (OR=1·95; P=0·004) suggesting that FOB testing was capturing some aspects of bowel morbidity associated with schistosomiasis as eggs perforate the bowel triggering a small release of blood into the intestinal lumen (Betson et al. 2010). Using these same data but classifying infection status on the basis of host antibodies to schistosome soluble egg antigen (SEA), an association between FOB and infection was still apparent (data not shown). In future, it will be interesting to ascertain how FOB levels change during the course of ongoing treatment with PZQ though it presently remains to be explained what are the causal factor(s) leading to the occurrence of FOB in those without schistosomiasis.

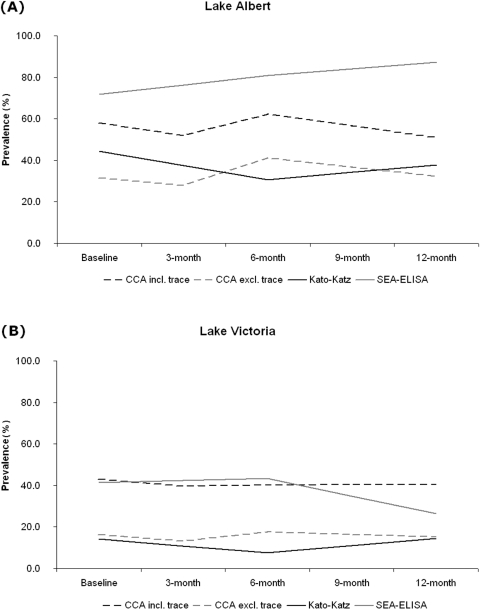

Fig. 5.

Longitudinal dynamics of the general prevalence (%) of antigen excretion in urine (CCA test), egg excretion in stool (Kato-Katz) and antibody response to eggs (SEA-ELISA) in Ugandan children aged ⩽6 years living in Lakes Albert (A) and Victoria (B) are rather stationary. Note: all children received PZQ treatment at baseline; then selective treatment undertaken at 3 months (positive by CCA test), at 6 months (positive by CCA test or Kato-Katz) and then mass treatment again given out at 12 months; no data were collected at 9 months. The graphs show that even with regular access to PZQ, intestinal schistosomiasis abounds within this study cohort.

Impact of PZQ treatment on prevalence and organomegaly

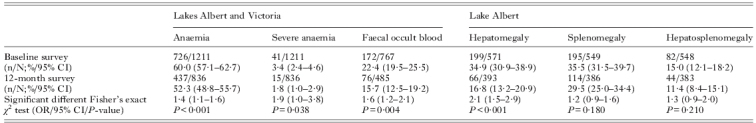

Over the course of two years, the prospective study cohort has also been inspected for levels of anaemia, splenomegaly and hepatomegaly, alongside diagnosis and treatment for malaria and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. Table 3 records the overall changes in the status of each variable at baseline and at follow-ups. Whilst general levels of prevalence of schistosomiasis have broadly shown stationarity during the course of these follow-up (see Fig. 3), there are some encouraging trends of morbidity reversion. For example, the decrease in FOB from 22·4% to 15·7% is of note potentially confirming the future use of FOB tests as markers of morbidity dynamics in the face of treatment. At the same time, the highly significant reductions of anaemia in this cohort are perhaps most likely due to the management of malaria with artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). Further multivariate analysis of these data and organomegaly statistics is ongoing and will be later reported in the fuller context of this longitudinal cohort study.

Table 3.

Summary of anaemia (Hb <110 mg/l), severe anaemia (Hb <70 mg/l) and faecal occult blood in children aged ⩽6 years from lakes Albert and Victoria at study baseline then at one year later; summary of enlarged livers (hepatomegaly), spleens (splenomegaly) and a combination of both (hepatosplenomegaly) as measured by abdominal palpation by project nurse in children from Lake Albert is shown

95% CI=95% confidence intervals prevalence and odds ratio (OR) values; n=number of children positive; N=total number of children surveyed.

Spatial micro-epidemiology and behavioural risks

It is clear that young children are infected with schistosomes largely depending on how, when and where their mothers draw water for domestic use and child-bathing practices. To shed detailed light on this aspect of water contact, Seto et al. (unpublished data) have used small global positioning system (GPS) dataloggers (Paz-Soldan et al. 2010; Stothard et al. 2011b) to record the movements of both mother and child pairs and their likely duration of exposure during a typical 3-day period. Analysis of these spatial patterns has provided a different insight into the social networks that exist between mother and child on the day-to-day level. For example, mothers spend on average more time (137 min) on the immediate lake shore, or the exposure zone, than their PSAC (112 min).

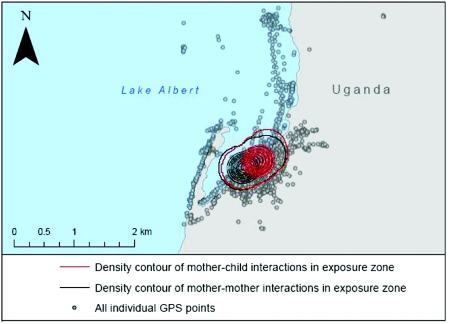

Of the mothers' time spent on the immediate lake shoreline, on average 15 min appear to have been spent interacting with other mothers, while 25 min were spent interacting with their PSAC. On the other hand, PSAC often spent time with other similar-aged children (34 min) on the lake shoreline. Fig. 6 attempts to illustrate that the locations of social interactions on the lake shoreline which are, in fact, quite spatially concentrated rather than dispersed across the shore. This suggests that not only can such wearable GPS-dataloggers be used to pinpoint the locations at which exposures occur, but also where social interactions are involved with water contact and putative exposure, locating times and places for future social-behavioural studies to help understand the local transmission biology for these younger children and perhaps devise appropriate interventions (Stothard et al. 2011a).

Fig. 6.

Local map of Bugoigo village on the shoreline of Lake Albert, Uganda with the GPS tracks of mothers and children overlaid across the map. The tracks were downloaded from GPS-dataloggers attached to the participant's wrist over a 3-day period. The red kernel and black kernel correspond to geographical locations of where most social interactions took place during the same time across the 3-day period. An important future consideration is to devise best ways to mitigate water contact within this mother and child group yet allowing them to undergo their daily tasks.

TOWARDS CHANGES IN INTERNATIONAL GUIDELINES

Given the potential scale of the problem of schistosomiasis in infants and PSAC across sub-Saharan Africa, a key challenge will be to gauge more precisely the total numbers of children living in need of treatment (Engels and Savioli, 2009; Utzinger et al. 2009). Without question, it is likely to be in the region of several millions, possibly even an order of magnitude higher; while a clear relationship between infection levels in SAC and PSAC has not been established yet, it is likely that the geographical distribution of PSAC at-risk will be largely restricted to the zones where general disease transmission is very high, for example, in areas where pre-NDCP prevalence in SAC is well in excess of 50%. Developing algorithms to delineate and strategically target such locations will become ever more important especially as control is rolled out reaching remoter areas where disease surveillance has been poor or previously lacking (Stothard et al. 2011a, b).

There will of course be some quicker geographical fixes than others, especially where the local epidemiological landscape is relatively simple, such as the transmission landscapes of the Great East Africa Lakes. In these areas, zones of intervention could largely be defined as fringing paths, or swaths, which track the immediate lake shoreline up to 1 km inland in which infants and PSAC will have likely had regular exposure to water containing schistosome cercariae. In future, epidemiological surveys should bring together household mapping technologies and remote sensing imagery, in the form of clear-cut intervention maps that are easily understood by politicians, health stakeholders and the receipts of control themselves (Dabo et al. 2011; Mutapi et al. 2011; Stothard et al. 2011a; Verani et al. 2011).

To move forward in a concerted manner, especially when several countries have to decide their own best course of actions, a revision of WHO guidelines will facilitate this move. In September 2010, an informal 2-day meeting took place at Geneva which brought together new evidence from several countries concerning the occurrence of schistosomiasis in the younger child as well as the performance of PZQ treatment for encouraging changes in its formal licensing or off-label use in treatment of young children. The outcomes from this meeting will be reported elsewhere as well as the advocating the need for pharmacokinetic studies (Keiser et al. 2011), but it is firmly assured that exciting progress will follow triggered by these first few steps within this international forum.

CONCLUSION: CLOSING THE ‘PZQ TREATMENT GAP’?

Treatment of younger children with PZQ is ethically warranted, proven to be safe and can be implemented successfully on the ground in the frame of preventive chemotherapy. Progressive scale-up of control, in areas of high endemicity, towards acceptance at the national level is now needed alongside changes in international guidelines and political commitment. If the above steps are taken and pharmacokinetic studies assist to further optimise pragmatic dosing, this PZQ treatment gap could be closed within the foreseeable future. By giving infants and PSAC access to medication this should lead to real progress in the management of paediatric schistosomiasis in the public health setting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This review takes a personalised view primarily focused on the work of the immediate authors and JRS would wish to draw attention to the research efforts of others, particularly Dr Bertrand Sellin, who has provided sound advice and original insight into this problem. We also thank Dr Lester Chitsulo for assistance in bringing together height-weight data from several countries, as well as hosting the meeting at WHO, Geneva in September 2010. The work has benefited from funding from the Wellcome Trust (JRS) – especially for funding the prospective cohort work in Uganda, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and USAID (AF). We would like to thank the BSP for providing funds for supporting of this Autumn Symposium on parasitic diseases in childhood. The views and opinions expressed by AFG and AM do not necessarily represent those of the WHO. This manuscript was improved by the helpful comments from Jürg Utzinger and Jennifer Keiser.

REFERENCES

- Beanland T. J., Lacey S. D., Melkman D. D., Palmer S., Stothard J. R., Fleming F., Fenwick A.. Multimedia materials for education, training, and advocacy in international health: experiences with the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative CD-ROM. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:87–90. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergquist R.. A century of schistosomiasis research. Acta Tropica. 2008;108:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethony J. M., Loukas A.. The schistosomiasis research agenda-what now. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;2:e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betson M., Figueiredo J. C. S., Rowell C., Kabatereine N. B., Stothard J. R.. Intestinal schistosomiasis in mothers and young children in Uganda: investigation of field-applicable markers of bowel morbidity. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;83:1048–1055. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosompem K. M., Bentum I. A., Otchere J., Anyan W. K., Brown C. A., Osada Y., Takeo S., Kojima S., Ohta N.. Infant schistosomiasis in Ghana: a survey in an irrigation community. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2004;9:917–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T. B., Liao C. W., D'Lamini P., Chang P. W. S., Chiu W. T., Du W. Y., Fan C. K.. Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium infection among inhabitants of Lowveld, Swaziland, an endemic area for the disease. Tropical Biomedicine. 2010;27:337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley D. G., Secor W. E.. A schistosomiasis research agenda. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2007;1:e32. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabo A., Badawi H. M., Bary B., Doumbo O. K.. Urinary schistosomiasis among preschool-aged children in Sahelian rural communities in Mali. Parasites and Vectors. 2011;4:21. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doenhoff M. J., Hagan P., Cioli D., Southgate V., Pica-Mattoccia L., Botros S., Coles G., Tchuem-Tchuenté L. A., Mbaye A., Engels D.. Praziquantel: its use in control of schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa and current research needs. Parasitology. 2009;136:1825–1835. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekpo U. F., Laja-Deile A., Oluwole A. S., Sam-Wobo S. O., Mafiana C. F.. Urinary schistosomiasis among preschool children in a rural community near Abeokuta, Nigeria. Parasites and Vectors. 2010;3:58. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels D., Chitsulo L., Montresor A., Savioli L.. The global epidemiological situation of schistosomiasis and new approaches to control and research. Acta Tropica. 2002;82:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels D., Savioli L.. Evidence-based policy on deworming. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2009;3:e359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick A., Savioli L., Engels D., Bergquist N. R., Todd M. H.. Drugs for the control of parasitic diseases: current status and development in schistosomiasis. Trends in Parasitology. 2003;19:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick A., Webster J. P., Bosque-Oliva E., Blair L., Fleming F. M., Zhang Y., Garba A., Stothard J. R., Gabrielli A. F., Clements A. C. A., Kabatereine N. B., Toure S., Dembele R., Nyandindi U., Mwansa J., Koukounari A.. The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI): rationale, development and implementation from 2002–2008. Parasitology. 2009;136:1719–1730. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009990400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French M. D., Churcher T. S., Gambhir M., Fenwick A., Webster J. P., Kabatereine N. B., Basanez M. G.. Observed reductions in Schistosoma mansoni transmission from large-scale administration of praziquantel in Uganda: A mathematical modelling study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2010;4:e897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garba A., Barkire N., Djibo A., Lamine M. S., Sofo B., Gouvras A. N., Bosque-Oliva E., Webster J. P., Stothard J. R., Utzinger J., Fenwick A.. Schistosomiasis in infants and preschool-aged children: infection in a single Schistosoma haematobium and a mixed S. haematobium-S. mansoni foci of Niger. Acta Tropica. 2010;115:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryseels B., de Vlas S. J.. Worm burdens in schistosome infections. Parasitology Today. 1996;12:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)80671-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P. J., Engels D., Fenwick A., Savioli L.. Africa is desperate for praziquantel. Lancet. 2010;376:496–498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60879-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P. J., Molyneux D. H., Fenwick A., Kumaresan J., Ehrlich-Sachs S., Sachs J. D., Savioli L.. Control of neglected tropical diseases. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1018–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra064142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen M. V., Sacko M., Vennervald B. J., Kabatereine N. B.. Leave children untreated and sustain inequity. Trends in Parasitology. 2007;23:568–569. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P., Webbe G. Human Schistosomiasis. William Heinemann Medical Books Ltd; London: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatereine N. B., Brooker S., Koukounari A., Kazibwe F., Tukahebwa E. M., Fleming F. M., Zhang Y. B., Webster J. P., Stothard J. R., Fenwick A.. Impact of a national helminth control programme on infection and morbidity in Ugandan schoolchildren. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:91–99. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.030353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser J., Ingram K., Utzinger J.. Antiparasitic drugs for paediatrics: systemtic review, formulations, pharmacokinetics, safety, efficacy and implications for control. Parasitology. 2011;138 doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000023. (in press, in this Special Issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C. H., Sturrock R. F., Kariuki H. C., Hamburger J.. Transmission control for schistosomiasis – why it matters now. Trends in Parasitology. 2006;22:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBeaud A. D., Malhotra I., King M. J., King C. L., King C. H.. Do antenatal parasite infections devalue childhood vaccination. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2009;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mafiana C. F., Ekpo U. F., Ojo D. A.. Urinary schistosomiasis in preschool children in settlements around Oyan Reservoir in Ogun State, Nigeria: implications for control. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2003;8:78–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T., Sekljic H., Fuchs S., Bothe H., Schollmeyer D., Miculka C.. Taste, a new incentive to switch to (R)-praziquantel in schistosomiasis treatment. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2009;3:e357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montresor A., Engels D., Chitsulo L., Bundy D. A. P., Brooker S., Savioli L.. Development and validation of a ‘tablet pole’ for the administration of praziquantel in sub-Saharan Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2001;95:542–544. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montresor A., Engels D., Ramsan M., Foum A., Savioli L.. Field test of the ‘dose pole’ for praziquantel in Zanzibar. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002;96:323–324. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90111-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutapi F., Rujeni N., Bourke C., Mitchell K., Appleby L., Nausch N., Midzi H., Mduluza T.. Schistosoma haematobium treatment in 1–5 year old children: safety and efficacy of the antihelminthic drug praziquantel. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease. 2011;5:e1143. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namwanje H., Kabtereine N. B., Olsen A.. The acceptability and safety of praziquantel alone and in combination with mebendazole in the treatment of Schistosoma mansoni and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in children aged 1–4 years in Uganda. Parasitology. 2011;138 doi: 10.1017/S0031182011000138. , (in press, in this Special Issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odogwu S. E., Ramamurthy N. K., Kabatereine N. B., Kazibwe F., Tukahebwa E., Webster J. P., Fenwick A., Stothard J. R.. Schistosoma mansoni in infants (aged <3 years) along the Ugandan shoreline of Lake Victoria <3 years) along the Ugandan shoreline of Lake Victoria. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2006;100:315–326. doi: 10.1179/136485906X105552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara K. N., Udoidung N. I., Ukpong I. G.. Genitourinary schistosomiasis among pre-primary schoolchildren in a rural community within the Cross River Basin, Nigeria. Journal of Helminthology. 2007;81:393–397. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X07853521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Soldan V. A., Stoddard S. T., Vazquez-Prokopec G., Morrison A. C., Elder J. P., Kitron U., Kochel T. J., Scott T. W.. Assessing and maximizing the acceptability of global positioning system device use for studying the role of human movement in dengue virus transmission in Iquitos, Peru. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2010;82:723–730. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perel Y., Sellin B., Perel C., Arnold P., Mouchet F.. Use of urine collectors for infants from 0 to 4 years of age in a mass survey of urinary schistosomiasis in Niger. Medecine Tropicale. 1985;45:429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savioli L., Gabrielli A. F., Montresor A., Chitsulo L., Engels D.. Schistosomiasis control in Africa: 8 years after World Health Assembly Resolution 54.19. Parasitology. 2009;136:1677–1681. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith F. M.. Bilharziasis in the African infant and child in the Mtoko district, Southern Rhodesia. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1958;4:287–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa-Figueiredo J. C., Basanez M. G., Mgeni A. F., Khamis I. S., Rollinson D., Stothard J. R.. A parasitological survey, in rural Zanzibar, of pre-school children and their mothers for urinary schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminthiases and malaria, with observations on the prevalence of anaemia. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 2008;102:679–692. doi: 10.1179/136485908X337607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa-Figueiredo J. C. Day M. Betson M. Kabatereine N. B. Stothard J. R. 2010aAn inclusive dose pole for treatment of schistosomiasis in infants and preschool children with praziquantel Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104740–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa-Figueiredo J. C. Pleasant J. Day M. Betson M. Rollinson D. Montresor A. Kazibwe F. Kabatereine N. B. Stothard J. R. 2010bTreatment of intestinal schistosomiasis in Ugandan preschool children: best diagnosis, treatment efficacy and side-effects, and an extended praziquantel dosing pole International Health 2103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard J. R. Gabrielli A. F. 2007aSchistosomiasis in African infants and preschool children: to treat or not to treat Trends in Parasitology 2383–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard J. R. Gabrielli A. F. 2007bResponse to Johansen et al.: Leave children untreated and sustain inequity Trends in Parasitology 23569–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard J. R., Pleasant J., Oguttu D., Adriko M., Galimaka R., Ruggiana A., Kazibwe F., Kabatereine N. B.. Strongyloides stercoralis: a field-based survey of mothers and their preschool children using ELISA, Baermann and Koga plate methods reveals low endemicity in western Uganda. Journal of Helminthology. 2008;82:263–269. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X08971996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard J. R. Sousa-Figuereido J. C. Betson M. Adriko M. Arinaitwe M. Rowell C. Besiyge F. Kabatereine N. B. 2011aSchistosoma mansoni infections in young children: When are schistosome antigens in urine, eggs in stool and antibodies to eggs first detectable PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 5e938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard J. R. Sousa-Figueiredo J. C. Betson M. Seto E. Y. W. Kabatereine N. B. 2011bInvestigating the spatial micro-epidemiology of diseases within a point-prevalence sample: a field applicable method for rapid mapping of households using low-cost GPS-dataloggers Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzinger J., Keiser J.. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: common drugs for treatment and control. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2004;5:263–285. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utzinger J., Raso G., Brooker S., de Savigny D., Tanner M., Ornbjerg N., Singer B. H., N'Goran E. K.. Schistosomiasis and neglected tropical diseases: towards integrated and sustainable control and a word of caution. Parasitology. 2009;136:1859–1874. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verani J. R., Abudho B., Montgomery S. P., Mwinzi P. N. M., Shane H. L., Butler S. E., Karanja D. M. S., Secor W. E.. Schistosomiasis among young children in Usoma, Kenya. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;84:787–791. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J. P., Koukounari A., Lamberton P. H. L., Stothard J. R., Fenwick A.. Evaluation and application of potential schistosome-associated morbidity markers within large-scale mass chemotherapy programmes. Parasitology. 2009;136:1789–1799. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009006350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster J. P., Oliviera G., Rollinson D., Gower C. M.. Schistosome genomes: a wealth of information. Trends in Parasitology. 2010;26:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Preventive Chemotherapy in Human Helminthiasis. WHO; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Schistosomiasis. Number of people treated, 2008. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2010;85:158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse M. E. J., Mutapi F., Ndhlovu P. D., Chandiwana S. K., Hagan P.. Exposure, infection and immune responses to Schistosoma haematobium in young children. Parasitology. 2000;120:37–44. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099005156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. B., MacArthur C., Mubila L., Baker S.. Control of neglected tropical diseases needs a long-term commitment. BMC Medicine. 2010;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]