Abstract

Background:

Phrynoderma is a type of follicular hyperkeratosis. Various nutritional deficiency disorders have been implicated in the etiology of phrynoderma.

Aim:

To determine clinical features of phrynoderma and its association with nutritional deficiency signs.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study of 125 consecutive patients with phrynoderma attending the outpatient department (OPD) of dermatology was conducted in a tertiary care hospital. In all patients, a detailed history was taken and cutaneous examination findings such as distribution, sites of involvement, morphology of the lesions, and signs of nutritional deficiencies were noted.

Results:

The proportion of patients with phrynoderma attending the OPD was 0.51%. There were 79 males and 46 females. Age of the patients was in the range of 3-26 years with a mean of 10 ± 4.3 years. The lesions were asymptomatic in 114 (91.2%) patients. The distribution of lesions was bilateral and symmetrical in 89 (71.2%) patients. The disease was localized (elbows, knees, extensor extremities, and/or buttocks) in 106 (84.8%) patients. The site of onset was elbows in 106 (84.8%) patients. The lesions were discrete, keratotic, follicular, pigmented or skin colored, acuminate papules in all patients. Signs of vitamin A and vitamin B-complex deficiency were present in 3.2% and 9.6% patients, respectively. Epidermal hyperkeratosis, follicular hyperkeratosis, and follicular plugging were present in the entire biopsy specimen.

Conclusion:

Phrynoderma is a disorder with distinctive clinical features and can be considered as a multifactorial disease involving multiple nutrients, local factors like pressure and friction, and environmental factors in the setting of increased nutritional demand.

Keywords: Follicular hyperkeratosis, nutritional deficiency, phrynoderma

Introduction

Phrynoderma, meaning toad skin, is a type of follicular keratosis coined and described by Nocholls in 1933.[1] Various nutritional deficiencies such as Vitamin (Vit) A, Vit B-complex, Vit E and Essential fatty acid (EFA) deficiency, as well as protein-calorie malnutrition have been suggested as possible etiological factors. However, the etiology of the disease is still controversial. Most of the studies on phrynoderma were conducted in the early and middle of the last century. A few anecdotal cases have been reported, especially from the developed countries.[2,3] Therefore, clinical features of phrynoderma and its association with nutritional deficiency signs were studied to elucidate the relationship between phrynoderma and nutritional status of patients.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study of 125 consecutive phrynoderma patients attending the outpatient department (OPD) of dermatology was conducted in a tertiary care hospital during a period of two years. In all patients, a detailed history with particular reference to age, gender, seasonal variations, socioeconomic status, and family history of disease and recurrences was recorded. Cutaneous examination findings such as distribution, sites of involvement, morphology of the lesions, and signs of nutritional deficiencies were noted. Phrynoderma was diagnosed clinically if a patient presents with discrete, brown or skin colored, acuminate, keratotic papules with central keratin plug predominantly distributed over elbows, knees, extensor extremities, and/or buttocks. All patients with phrynoderma examined by the investigator, irrespective of age and gender, were included in the study. Whenever required, a skin biopsy was performed for histopathological study.

Results

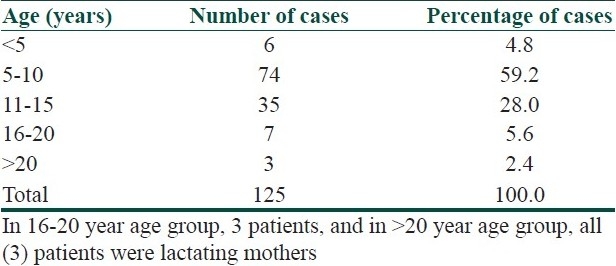

The proportion of patients with phrynoderma attending OPD was 0.51%. Among 125 patients, 79 (63.2%) were male and 46 (36.8%), female. The age of the patients was in the range of 3-26 years, with a mean of 10 ± 4.3 years [Table 1]. A majority of the patients (88%) were from low socioeconomic group and the remaining (12%) were from middle socioeconomic group. Phrynoderma was common in students (94.4%), followed by lactating mothers (4.8%) and laborers (0.8%). The family history of phrynoderma was present in three (2.4%) patients. The disease was recurrent in 17 (13.6%) patients. During a calendar year, 8.33% of the patients presented during summer, 46.7% in the rainy, and 45% in winter season.

Table 1.

Age distribution of phrynoderma cases

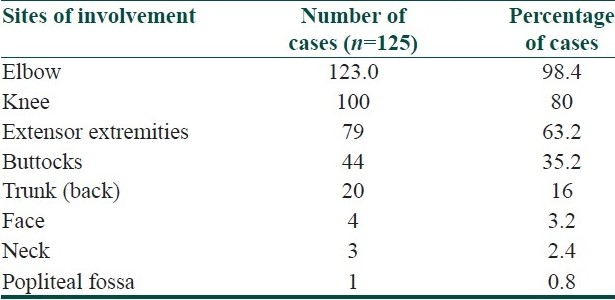

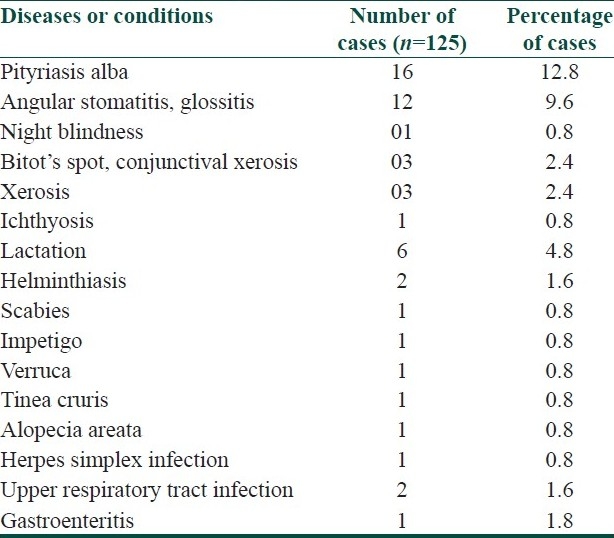

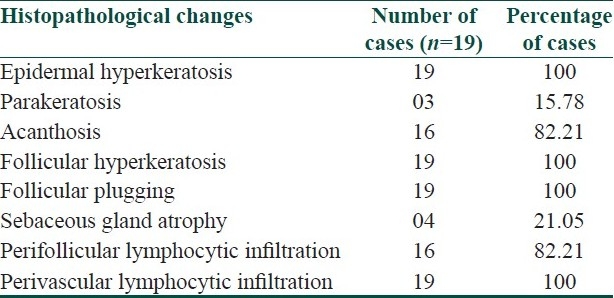

The lesions were asymptomatic in 114 (91.2%) patients and mild itching was present in 11 (8.8%) patients. The distribution of lesions was bilateral and symmetrical in 89 (71.2%) patients. The disease was localized (elbows, knees, extensor extremities, and/or buttocks) in 106 (84.8%) patients and generalized (trunk and/or face) in 19 (15.2%) patients. Elbows and buttocks alone were affected in 16 (12.8%) and 2 (1.6%) patients, respectively [Table 2]. The site of onset was elbows in 106 (84.8%) patients, followed by knees (8%), buttocks (4%), and extensor extremities (4%). In all (100%) patients, the lesions were discrete, keratotic, acuminate, and brown to skin colored papules with central keratinous plug [Figure 1]. The surrounding skin was dry and scaly in 44 (35.2%) patients and pigmented in 72 (57.6%) patients. Various diseases or conditions were noted in association with phrynoderma [Table 3]. Histopathological study was performed in 19 patients [Table 4].

Table 2.

Sites of involvement in phrynoderma

Figure 1.

Discrete brown to skin colored keratotic, follicular, acuminate papules with central keratinous plug localized to elbows

Table 3.

Associated diseases or conditions in phrynoderma

Table 4.

Histopathological changes in phrynoderma

Discussion

Phrynoderma is a disease occurring in children and adolescents aged between 5 and 15 years. The disease is uncommon (<5%)[4,5] in children below 5 years of age. In the present study, phrynoderma was also noticed in three adult female patients who were all lactating mothers. Thus, increased nutritional demand during childhood and lactation, and the lack of good nutrition due to low socioeconomic status may be responsible for occurrence of phrynoderma in these patients. There is no clear consensus regarding gender distribution. Male[4,5] or female[6,7] preponderance and equal gender distribution[8] have been reported. The proportion of phrynoderma cases in the present study is less compared to other studies where it was found to be 1.3%,[4] 3%,[8] and 5%.[7] These studies were conducted in the middle of last century. The decline in the proportion of phrynoderma patients over the past few decades may be attributed to implementation of national nutritional programs and improved nutritional status. Therefore, nutrition seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of phrynoderma.

In many studies including the present one, the family history of phrynoderma was very low (0%,[7] 3.57%,[4] and 5%[8]). The absence of the disease in siblings who are also taking the same diet suggests the role of other factors in the manifestation of phrynoderma. The distribution and site of onset of lesions indicate importance of pressure and friction in the development of lesions. The incidence of phrynoderma is higher in the cooler months of the year, as is documented in the present study.[6] The flare up of the disease duirng winter may be due to follicular prominence, which generally occurs in otherwise normal children during cold weather.[9]

The reports on the distribution and morphology of lesions are consistent in all studies. The typical case of phrynoderma presents with bilaterally symmetrical discrete, keratotic, follicular, brown or skin colored, acuminate papules with central keratinous plug localized to elbows, knees, buttocks, and extensor extremities. In generalized disease, the lesions also appear on the trunk and face. These distinct clinical features help in differentiating phrynoderma from other common follicular keratotic disorders such as keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and follicular lichen planus.

Although the occurrence of phrynoderma has been related to nutritional status of the patient, in the present study, the signs and symptoms of nutritional deficiency were noted in less number of patients.

The ocular manifestations of Vit A deficiency in patients with phrynoderma have been reported to be 5%.[8] These manifestations are common in children below 5 years of age.[6] It has also been demonstrated that the incidence of phrynoderma is less where the prevalence of signs of Vit A deficiency is high and vice versa.[10] Extremely low levels of serum Vit A, 0.1 μmol/L (normal, 1.4-4 μmol/L) has been reported secondary to Vit A malabsorption, following small bowel bypass surgery for obesity,[11,12] colectomy,[13] and in pancreatic insufficiency.[14] All these patients presented with phrynoderma and responded to Vit A therapy. However, in the present study, none of the patients underwent such surgeries. Moreover, malabsorption of a single nutrient is highly unlikely. Diet survey and serum Vit A levels in apparently healthy phrynoderma patients and normal controls revealed no statistically significant difference between the two groups.[10,15] Phrynoderma has been reported even in individuals who were fed Vit A rich diet.[7] The response to Vit A therapy may be attributed to its effect on keratinization.

The Vit A deficiency as a cause of phrynoderma was largely based on the therapeutic response to cod liver oil, which was considered to be a source of Vit A. However, later it has also been demonstrated as a source of EFA.[6] The patients presenting with signs of Vit B-complex deficiency were less in number when compared to other studies (47.6%,[16] 50%,[17] 65%,[4] 92%,[6] and 25%[5]). None of the patients in the present study presented with nutritional deficiency signs of EFA, Vit E, and Vit C or protein calorie malnutrition. Regarding EFA intake in India, the computation based on revised figures of fat content in cereals and pulses has shown that the invisible fat present even in the poorest of Indian diet provides minimum amount of linoleic acid needed, ie, 3% of total energy.[18,19] The ratio of eicosatrienoic acid and arachidonic acid >0.4 is considered as an accurate indicator of EFA deficiency.[20] The studies showing EFA deficiency in phrynoderma patients used alkaline isomerization (AI) method for estimation of fatty acid levels.[21,17] In AI, the fatty acids are estimated according to the number of double bonds and their chain length is not taken into consideration, thereby overestimating the dienoic and trienoic acids, and underestimating the tetraenoic and pentaenoic acids. This results in high trienoic to tetraenoic acid ratio. In gas exchange chromatography (GC) method, fatty acids are estimated according to both double bonds and chain length. Thus, the ratio obtained by GC method reflects EFA deficiency.[20] In phrynoderma patients, this ratio was found to be 0.12, which is normal.[19,20] The levels of linoleic acid and phospholipids (sensitive indicators of EFA deficiency), and ratio of linoleic to arachidonic acid (indicator of efficient conversion of linoleic acid to arachidonic acid) were also normal in phrynoderma patients.[19]

The cutaneous manifestations of riboflavin, pyridoxine, niacin, and EFA deficiency states have a number of similarities. Intersecting biochemical pathways that involve these nutrients may explain the common cutaneous findings. Riboflavin is required for pyridoxine metabolism, which, in turn, is required for tryptophan-niacin metabolism, and niacin is necessary for fatty acid synthesis.[22] The combination therapy of Vit B-complex and EFA[6,16] or Vit B-complex and Vit E[18] have shown better results when compared to single drug therapy. The serum levels of linoleic acid[19,20] and Vit E[18] also increased significantly during the combination therapy. Vitamins of B-complex group when used alone failed to show any therapeutic response.[6,23,24] In addition, deficiency of a single vitamin of B-complex group is rare because poor nutritional diets or malabsorption are more often associated with multiple nutritional deficiencies.[4]

Thus, phrynoderma is not a disease with single etiology. Multiple nutrients play a role in the pathogenesis of phrynoderma. Impaired balance or threshold levels of these nutrients with or without a deficiency state seem to alter the intersecting biochemical pathways and the local milieu of these nutrients resulting in phrynoderma. This can be compared with the formation of comedones in acne where a low level of linoleic acid in sebum has been attributed in the pathogenesis of follicular hyperkeratinization.[25] Follicular hyperkeratosis with keratin plugging along with epidermal hyperkertosis and acanthosis are the characteristic features of phrynoderma. Atrophied sebaceous glands are usually seen on serial sections in phrynoderma.[26,27] The clinical and histopathological skin changes closely resembling those of phrynoderma have been noted in rats, which were fed with fat-deficient diet.[26] Hence, an abnormality in the EFA metabolism in the pilosebaceous unit caused by Vit B-complex appears to be the important step in the pathogenesis of phrynoderma.

The main drawback of the present study is lack of biochemical evidence of nutritional status (serum levels of nutrients) of patients. These investigations were not done because of their non-availability in a resource poor set-up. Normal serum levels of nutrients (Vit A, Vit B-complex, EFA) have been reported in phrynoderma patients. However, with the available literature and our findings, it can be hypothesized that phrynoderma may be a multifactorial disease involving multiple nutrients, local factors like pressure and friction, and environmental factors manifesting in the setting of increased nutritional demand. Further prospective case-control studies investigating the levels of Vit B-complex, Vit A, Vit E, and EFA in the blood and skin, and also in relation to the treatment are required to delineate the exact pathogenesis of phrynoderma.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: A condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gaz. 1933;68:681–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Girard C, Dereure O, Blatiere V, Guillot B, Bessis D. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma associated with chronic giardiasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:346–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marron M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: A manifestation of Vitamin A deficiency? the rest of the history. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayyangar MC. Phrynoderma and nutritional deficiency. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1967;33:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajagopal K, Chowdhury SR. Phrynoderma and some associated changes in blood lipids. Indian Med Gaz. 1952;87:350–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gopalan C. The etiology of phrynoderma. Indian Med Gaz. 1947;82:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5478.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panja SK, Chaterjee SK, Mukherjee KL. Follicular keratosis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 1970;15:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopalan C. Some cutaneous disorders related to malnutrition. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1957;23:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aykroyd WR, Rajagopal K. The state of nutrition of school children in south India. Indian J Med Res. 1936;24:419–37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barr DJ, Riley RJ, Greco DJ. Bypass phrynoderma. Vitamin A deficiency associated with bowel bypass surgery. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:919–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.7.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, Sullivan J. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: Due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:322–4. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neil SM, Pembroke AC, du-Viver AW, Salisbury JR. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171–2. doi: 10.1177/014107688808100319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma. Histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/7.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srikantia SG, Belavady B. Clinical and biochemical observationa in phrynoderma. Indian J Med Res. 1961;49:109–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhat KS, Belavady B. Biochemical studies in phrynoderma (follicular hyperkeratosis). II. Polyunsaturated fatty acid levels in plasma and erythrocytes of patients suffering from phrynoderma. Am J Clin Nutr. 1967;20:386–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/20.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadiger HA. Role of Vitamin E in the etiology of phrynoderma (follicular hyperkeratosis) and its relationship with B-complex vitamins. Br J Nutr. 1980;44:211–4. doi: 10.1079/bjn19800033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: Is it an EFA deficiency disease? Eur J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghafoorunissa Essential fatty acid nutritional status in phrynoderma. Indian J Med Res. 1984;80:663–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christiansen EN, Piyasena C, Bjorneboe GE, Bibow K, Nilsson A, Wandel M. Vitamin E deficiency in phrynoderma cases fro Srilanka. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:253–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller SJ. Nutritional deficiency and skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ive FA. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:117–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srikantia SG. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:736. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downing DT, Stewart ME, Wertz PW, Strauss JS. Essential fatty acids and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:221–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramalingaswamy V, Sinclair HM. The relation of deficiency of vitamin A and of essential fatty acids to follicular hyperkeratosis in the rat. Br J Med. 1953;65:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1953.tb13159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao MV. ‘Phrynoderma’- A clinical and histopathological study. Indian J Med Res. 1937;24:727–36. [Google Scholar]