Abstract

Background:

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignant skin tumor. Although mortality attributable to BCC is not high, the disease is responsible for considerable morbidity. There is evidence that the number of patients who develop more than one BCC is increasing.

Aims:

The aim of this study was to elucidate possible risk factors for developing Multiple BCC.

Patients and Methods:

Patients with histologically proven BCC (n = 218) were divided into two groups (single BCC and Multiple BCC) according to the number of their tumors and their profile were reviewed. Probable risk factors were compared between these two groups.

Results:

Among 33 evaluated risk factors, mountainous area of birth, past history of BCC, history of radiotherapy (in childhood due to tinea capitis), abnormal underlying skin at the site of tumor, and pigmented pathologic type showed significant differences between the two groups.

Conclusions:

The high rate of additional occurrences of skin cancers among patients with previously diagnosed BCC emphasizes the need of continued follow-up of these individuals. Those with higher risk require closest screening.

Keywords: Basal cell carcinoma, multiple basal cell carcinomas, non-melanocytic skin cancer, radiotherapy, risk factor

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignant skin tumor.[1,2] Although mortality attributable to BCC is not high, the disease is responsible for considerable morbidity and thus imposes a growing burden on health care services. Local tissue destruction and disfigurement can be large, if not limited by early detection and treatment.[1,3]

There is evidence that the number of patients who develop more than one BCC is increasing;[3,4] it is clear that all the problems of patients with single BCC are multiplied in ones with multiple BCC (mBCC).

Furthermore, the number of non-melanocytic skin cancers (NMSC) is a risk factor not only for recurrence of previous tumor,[5] but also for the formation of new ones.[6] So, patients with mBCC are prone to both recurrence of previous tumor and development of new BCCs.[5–8] Risk of other cancers also appears to be increased among patients with mBCC.[9,10]

On the other hand, chemopreventive studies have demonstrated the ability of retinoids to prevent the development of skin cancers, particularly in patients with mBCC.[11]

So the identification of risk factors of mBCC is very important; thus, the high-risk patients can be recognized and followed up for recurrence and/or development of new tumor(s), trained to examine their skin regularly and visit their physician, as soon as a new skin lesion is formed, and screened serially for other malignancies.

Several factors have been suggested as risk factors of mBCC development in different previous studies, such as age,[12,13] male sex,[14] skin phototype (I, II),[14,15] frequent sun exposure and sunburn,[3,16] severe actinic damage,[15] history of radiotherapy,[17] numbers of tumors already present,[7,8,18] tumor size >1 cm,[12] truncal tumor,[19–21] family history of skin tumors,[22] low DNA repair capacity,[23] glutathione S-transferase and cytochrome P450 polymorphism,[14,24] tumor necrosis factor (TNF) microsatellite polymorphism,[14,25] and PTCH gene polymorphism.[26]

The purpose of this study was to evaluate clinical risk factors in patients with mBCC.

Patients and Methods

Patients with histologically proven BCC, who were referred to our skin tumor clinic (n = 218), were divided into two groups (single BCC and mBCC) according to the number of their tumors. Patients with xeroderma pigmentosa, nevoid BCC syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Bazex syndrome, or any other well-defined syndrome with mBCC were excluded. All these patients had been visited and examined by expert dermatologists to ensure data accuracy. Their profiles were reviewed for age at the time of tumor appearance, sex, previous and present outdoor work, history of smoking, drug abuse and alcohol consumption, past medical history and family history of cutaneous and non-cutaneous cancers, birth area, and previous and present residency area. Patients’ birth area and previous and present residency area were categorized into three subgroups: “tropical and subtropical”, “Caspian”, and “mountainous”, according to our National Geographic Institute classification. Skin phototype, eye and hair color, photo damaging lesions (including freckle, deep facial wrinkles, cutis rhomboids, telangiectasia, senile comedones, seborrheic keratosis, senile lentigo, actinic keratosis), recreational sun exposure, arsenic exposure, history of radiotherapy, date of radiotherapy, underlying skin at the site of tumor, history of trauma to tumor site, anatomic site of tumor, and tumor pathology were recorded as well.

Statistical analysis

The involvement of the various factors in the development of mBCC was analyzed by logistic regression. SPSS statistical software package for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Of all the 218 patients who entered the study with histologically confirmed BCC, 146 patients (67%) had single BCC and 72 (33%) had mBCC. The number of tumors in mBCC group varied between 2 and 30, with a mean of 3.9 and standard deviation of 4.2.

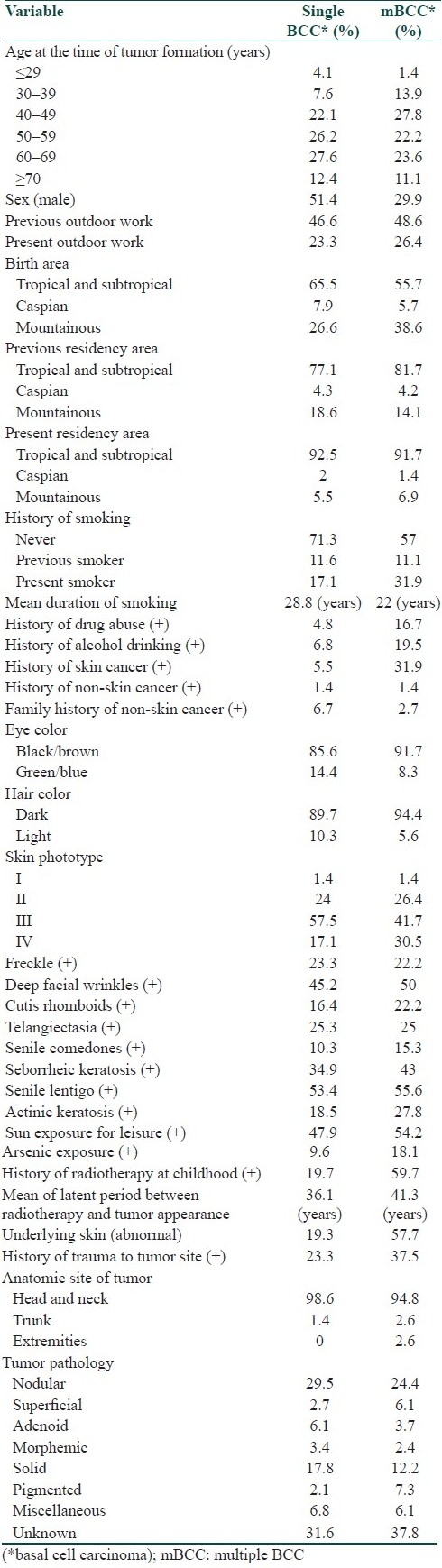

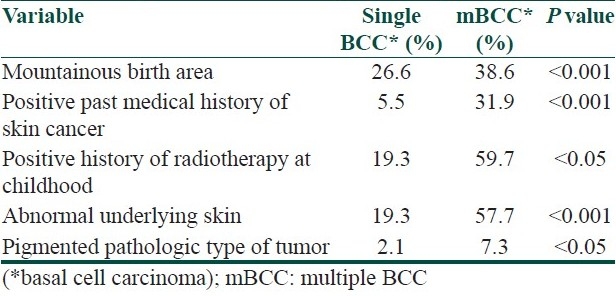

Neither any statistical difference was detected when testing for age at the time of tumor appearance, sex, previous or present outdoor work, previous or present residency area, history of smoking, drug abuse, and alcohol consumption, history of trauma to tumor site, personal or family history of non-skin cancer, nor could we discover any significant risk of mBCC when testing for eye or hair color, skin phototype, freckle, deep facial wrinkles, cutis rhomboids, telangiectasia, senile comedones, seborrheic or actinic keratosis, recreational sun exposure, arsenic exposure, anatomic site of tumor [Table 1]. From several parameters which were investigated in this study, mountainous birth area, past medical history of BCC, history of radiotherapy (in childhood due to tinea capitis), abnormal underlying skin at tumor site, and pigmented pathologic type of tumor showed significant differences between the two groups [Table 2].

Table 1.

Frequency of studied parameters in single BCC and multiple BCC (mBCC) groups

Table 2.

Risk factors with significant differences between single BCC and multiple BCC groups

Discussion

We investigated the clinical risk factors associated with mBCC in comparison with single BCC.

We found that the patients who were born in mountainous area had significantly increased risk of mBCCs. To our knowledge, this had not been reported before. One possible explanation could be the genetic susceptibility secondary to ethnic affinity. The genetic factors associated with mBCC, particularly PTCH gene polymorphism,[26] have been investigated in several studies; glutathione S-transferase, cytochrome P450 and TNF polymorphism have been suggested as other genetically determined risk factors for mBCC.[14,24,25]

From personal history and family history of skin and non-skin cancers, it was found that only personal history of skin cancer was significantly associated with mBCC in our study. This result is comparable with the result of several previous studies which reported the number of BCC as the main risk factor for development of a new tumor.[7,8,18] Our data suggest that history of radiotherapy is a strong risk factor for mBCCs. All patients with positive history of radiotherapy had received it because of tinea capitis at childhood. However, latent period between radiotherapy and tumor appearance showed no significant difference between the two groups.

We also found that abnormal underlying skin – including radiodermatitis, scar, chronic ulcer, actinic elastosis, and nevus – at the site of tumor was significantly more common among patients with mBCC; as this includes radiodermatitis too, this result may be secondary to history of radiotherapy and have an overlap with it.

Our data showed that pigmented pathologic type of BCC was significantly associated with mBCC. Czarencki et al. reported that the type of NMSC at presentation did not affect the rate of development of new lesions. However, they added that this factor may be important when patients are followed for longer.[27] As pathologic type of BCC was undetermined in some of our patients, more accurate evaluation of this factor is advisable.

Male sex and old age were identified as significant risk factors in some studies. These studies have reported that men and those over the age of 60 years were at increased risk for mBCC,[12,14] but other studies did not confirm it.[13] In our study, sex and age were not significant risk factors for mBCC.

A popular belief is that BCC is the result of cumulative life exposure to UV radiation. Some studies have suggested a different etiology, indicating that sun exposure before the age of 20 years and also intermittent sun exposure could be more important in the development of BCC.[28,29] Our results do not support this notion, as neither outdoor work nor recreational sun exposure (intermittent sun exposure) was found as significant factors in our study. Furthermore, none of the photodamaging lesions (freckle, deep facial wrinkles, cutis rhomboids, telangiectasia, senile comedon, seborrheic keratosis, senile lentigo, and actinic keratosis) was associated with mBCCs in our study.

Some studies have suggested that the rate of new NMSC formation appeared to be higher in populations living near the equator,[15,27] but residency area was not found as a significant risk factor in our study.

Smoking, drug abuse, and alcohol drinking did not show significant differences between the two groups. Similarly, Lear et al. reported no significant difference between mBCC and single BCC in terms of smoking history.[3] However, to our knowledge, neither drug abuse nor alcohol drinking was investigated in previous studies.

Conflicting results have been reported about skin phototype. An inability to tan (skin phototypes I and II) was identified as a significant risk factor in some large studies,[15] but other studies did not find it as a significant risk factor for mBCC. A significant relationship was not found between skin phototype and risk of new BCC formation in our study, as well.

Hair and eye color were not significant risk factors in our study. Arsenic exposure was also not found as a risk factor for mBCC.

Several studies have reported that the patients whose first BCC was truncal were significantly at higher risk of mBCC.[19–21] We could not evaluate this factor, as we had only four patients with truncal tumors, which were not enough for statistical analysis. This was a limitation of our study. Furthermore, as our investigation was a retrospective study based on recorded data in patients’ profile, we could not evaluate the role of some possible risk factors such as tumor size and patients’ genotypes for glutathione S-transferase, cytochrome P450, TNF and PTCH gene polymorphism in our study. Further prospective studies are required to evaluate these factors.

In conclusion, we tried to elucidate some risk factors among patients with mBCC. We found mountainous birth area, past medical history of BCC, history of radiotherapy at childhood, abnormal underlying skin and pigmented pathologic type of tumor as significant risk factors of mBCC. Anyway, the high rate of additional occurrences of skin cancers among patients with previously diagnosed BCC emphasizes the need for continued follow-up of these individuals. Those with higher risk require closest screening.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Lear W, Dahlke E, Murray CA. Basal cell carcinoma: Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and associated risk factors. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11:19–30. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madan V, Hoban P, Strange RC, Fryer AA, Lear JT. Genetics and risk factors for basal cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lear JT, Tan BB, Smith AG, Bowers W, Jones PW, Heagerty AH, et al. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma in the UK: Case-control study in 806 patients. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:371–4. doi: 10.1177/014107689709000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marghoob A, Kopf AW, Bart RS, Sanfilippo L, Silverman MK, Lee P, et al. Risk of another basal cell carcinoma developing after treatment of a basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:22–8. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70003-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czarnecki D, Staples M, Mar A, Giles G, Meehan C. Reccurrent non melanoma skin cancer in Southern Australia. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:410–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1996.tb03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantwell MM, Murray LJ, Catney D, Donnelly D, Autier P, Boniol M, et al. Second primary cancers in patients with skin cancer: A population-based study in Northern Ireland. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:174–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Ruczinski I, Jorgensen TJ, Yenokyan G, Yao Y, Alani R, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer and risk for subsequent malignancy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1215–22. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcil I, Stern RS. Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524–30. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.12.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karagas MR, Greenberg ER, Mott LA, Baron JA, Ernster VL. Occurrence of other cancers among patients with basal cell and squamous cell skin cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Troyanova P, Danon S, Ivanova T. Nonmelanoma skin cancers and risk of subsequent malignancies: A cancer registry-based study in Bulgaria. Neoplasma. 2002;49:81–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell RM, DiGiovanna JJ. Skin cancer chemoprevention with systemic retinoids: An adjunct in the management of selected high-risk patients. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19:306–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Iersel CA, van de Velden HV, Kusters CD, Spauwen PH, Blokx WA, Kiemeney LA, et al. Prognostic factors for a subsequent basal cell carcinoma: Implications for follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1078–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levi F, Randimbison L, Maspoli M, Te VC, La Vecchia C. High incidence of second basal cell skin cancers. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1505–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran S, Fryer AA, Lovatt TJ, Smith AG, Lear JT, Jones PW, et al. Combined effects of gender, skin type and polymorphic genes on clinical phenotype: Use of rate of increase in numbers of basal cell carcinomas as a model system. Cancer Lett. 2003;189:175–81. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00516-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, Baron JA, Mott LA, Stern RS. Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. JAMA. 1992;267:3305–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallberg P, Kaaman T, Lindberg M. Multiple basal cell carcinoma. A clinical evaluation of risk factors. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:127–9. doi: 10.1080/000155598433467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badri T, Zeglaoui F, Kochbati L, Kooli H, El Fekih N, Fazaa B, et al. Multiple basal cell carcinomas following radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal cancer. Presse Med. 2006;35:55–7. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(06)74520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Revenga F, Paricio JF, Vázquez MM, Del Villar V. Risk of subsequent non-melanoma skin cancer in a cohort of patients with primary basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:514–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lear JT, Smith AG, Strange RC, Fryer AA. Patients with truncal basal cell carcinoma represent a high-risk group. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:373. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovatt TJ, Lear JT, Bastrilles J, Wong C, Griffiths CE, Samarasinghe V, et al. Associations between ultraviolet radiation, basal cell carcinoma site and histology, host characteristics, and rate of development of further tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:468–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran S, Fryer AA, Smith A, Lear J, Bowers B, Jones PW, et al. Cutaneous basal cell carcinomas: Distinct host factors are associated with the development of tumors on the trunk and on the head and neck. Cancer. 2001;92:354–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2<354::aid-cncr1330>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallberg P, Kaaman T, Lindberg M. Multiple basal cell carcinoma, a clinical evaluation of risk factors. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:127–9. doi: 10.1080/000155598433467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei Q, Matanoski GM, Farmer ER, Hedayati MA, Grossman L. DNA repair related to multiple skin cancers and drug use. Cancer Res. 1994;54:437–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramachandran S, Fryer AA, Smith AG, Lear JT, Bowers B, Hartland AJ, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: Association of allelic variants with a high-risk subgroup of patients with the multiple presentation phenotype. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:247–54. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200104000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajeer AH, Lear JT, Ollier WE. Preliminary evidence of an association of tumour necrosis factor microsatellites with increased risk of multiple basal cell carcinomas. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:441–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strange RC, El-Genidy N, Ramachandran S. PTCH polymorphism is associated with the rate of increase in basal cell carcinoma numbers during follow-up: Preliminary data on the influence of an exon 12-exon 23 haplotype. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;44:469–76. doi: 10.1002/em.20068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czarnecki D, Mar A, Staples M, Giles G, Meehan C. The development of non melanocytic skin cancers in people with a history of skin cancer. Dermatol. 1994;189:364–7. doi: 10.1159/000246880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kricker A, Armstrong BK, English DR, Heenan PJ. Does intermittent sun exposure cause basal cell carcinoma?: A case-control study in Western Australia. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:489–94. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz Lascano A, Kuznitzky R, Garay I, Ducasse C, Albertini R. Risk factors for basal cell carcinoma. Case-control study in Cordoba. Medicina (B Aires) 2005;65:495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]