Abstract

There is increasing, but largely indirect, evidence pointing to an effect of commensal gut microbiota on the central nervous system (CNS). However, it is unknown whether lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus could have a direct effect on neurotransmitter receptors in the CNS in normal, healthy animals. GABA is the main CNS inhibitory neurotransmitter and is significantly involved in regulating many physiological and psychological processes. Alterations in central GABA receptor expression are implicated in the pathogenesis of anxiety and depression, which are highly comorbid with functional bowel disorders. In this work, we show that chronic treatment with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) induced region-dependent alterations in GABAB1b mRNA in the brain with increases in cortical regions (cingulate and prelimbic) and concomitant reductions in expression in the hippocampus, amygdala, and locus coeruleus, in comparison with control-fed mice. In addition, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) reduced GABAAα2 mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, but increased GABAAα2 in the hippocampus. Importantly, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) reduced stress-induced corticosterone and anxiety- and depression-related behavior. Moreover, the neurochemical and behavioral effects were not found in vagotomized mice, identifying the vagus as a major modulatory constitutive communication pathway between the bacteria exposed to the gut and the brain. Together, these findings highlight the important role of bacteria in the bidirectional communication of the gut–brain axis and suggest that certain organisms may prove to be useful therapeutic adjuncts in stress-related disorders such as anxiety and depression.

Keywords: brain–gut axis, irritable bowel syndrome, probiotic, fear conditioning, cognition

There is increasing evidence suggesting an interaction between the intestinal microbiota, the gut, and the central nervous system (CNS) in what is recognized as the microbiome–gut–brain axis (1–4). Studies in rodents have implicated dysregulation of this axis in functional bowel disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome. Indeed, visceral perception in rodents can be affected by alterations in gut microbiota (5). Moreover, it has been shown that the absence and/or modification of the gut microflora in mice affects the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis response to stress (6, 7) and anxiety behavior (8, 9), which is important given the high comorbidity between functional gastrointestinal disorders and stress-related psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression (10). In addition, pathogenic bacteria in rodents can induce anxiety-like behaviors, which are mediated via vagal afferents (9, 11).

GABA is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter of the CNS, the effects of which are mediated through two major classes of receptors—the ionotropic GABAA receptors, which exist as a number of subtypes formed by the coassembly of different subunits (α, β, and γ subunits; ref. 12), and the GABAB receptors, which are G protein coupled and consist of a heterodimer made up of two subunits (GABAB1 and GABAB2), both of which are necessary for GABAB receptor functionality (13). These receptors are important pharmacological targets for clinically relevant antianxiety agents (e.g., benzodiazepines acting on GABAA receptors), and alterations in the GABAergic system have important roles in the development of stress-related psychiatric conditions.

Probiotic bacteria are living organisms that can inhabit the gut and contribute to the health of the host (14). Accumulating clinical evidence suggests that probiotics can modulate the stress response and improve mood and anxiety symptoms in patients with chronic fatigue and irritable bowel syndrome (15, 16). One such organism is Lactobacillus rhamnosus (JB-1), which has been demonstrated to modulate the immune system because it prevents the induction of IL-8 by TNF-α in human colon epithelial cell lines (T84 and HT-29) (17) and modulates inflammation through the generation of regulatory T cells (18). Moreover, it inhibits the cardio–autonomic response to colorectal distension (CRD) in rats (19), reduces CRD-induced dorsal root ganglia excitability (20), and affects small intestine motility (21).

It is currently unclear whether potential probiotics such as L. rhamnosus (JB-1) could affect brain function, especially in normal, healthy animals. To this end, we sought to assess whether this bacteria could mediate direct effects on the GABAergic system. In parallel, behaviors relevant to GABAergic neurotransmission and the stress response were assessed subsequent to L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration. Finally, the role of the vagus nerve in mediating such effects was also investigated by examining these parameters in subdiaphragmatically vagotomized mice.

Results

Behavioral Effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) Administration.

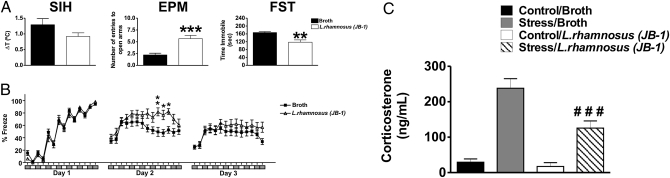

A battery of behavioral tests relevant to anxiety and depression was carried out. The stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH) and elevated plus maze (EPM) tests are widely used for assessing functional consequences of alterations in GABA neurotransmission (22, 23). Chronic administration of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) produced a nonsignificant reduction in SIH (t = 1.567, df = 34; P = 0.1263; Fig. 1A). On the EPM, animals treated with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) had a larger number of entries to the open arms than broth-fed animals, suggesting anxiolytic effects (open arm entry defined as all four paws entering the arms of the EPM apparatus) (t = 4.662, df = 34; P < 0.001; Fig. 1A). This effect is also reflected in the percentage of time spent in the open arms, although this observation did not reach statistical significance [broth v. L. rhamnosus (JB-1): 25.28 ± 6.67% vs. 38.36 ± 7.99%; t = 1.267, df = 34; P = 0.2146].

Fig. 1.

Effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration on behavior and stress-induced levels of corticosterone. (A) Stress-induced hyperthermia (SIH). There were no significant differences between L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed (n = 16) and broth-fed animals (n = 20). Elevated plus maze (EPM). Mice fed with the Lactobacillus (n = 16) entered significantly more times (***P < 0.001) into the open arms of the EPM apparatus in comparison with broth-fed mice (n = 20). (C) Forced swim test (FST). Animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (n = 8) spent less time immobile (**P < 0.01) compared with broth-fed mice (n = 8). (B) Effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on fear-related behaviors. On day 1, analysis revealed no differences in the learning curves between L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice (n = 16) and broth-fed control animals (n = 20). On day 2 (memory testing), L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treated animals displayed an enhanced memory towards cues (represented by the white boxes underneath the x axis. **P< 0.01 for cue no. 5 and *P < 0.05 for cue no. 6) and context (represented by the grey boxes underneath the x axis. *P < 0.05 for context 6). On day 3 (memory extinction), no differences were observed between the two treatment groups. (C) Effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration on stress-induced levels of corticosterone. Stress-induced corticosterone was measured in plasma 30 min after FST. Stress-induced levels of corticosterone are significantly lower in L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice compared with broth fed control animals (###P < 0.001).

Fear conditioning is also an ideal method for assessing cognitive aspects of anxiety behavior, and the response to context and specific cues are thought to reflect alterations in hippocampus and amygdala, respectively (24, 25) Analysis of the overall 3-d freezing behavior (the total percentage of freezing behaviors on each day) showed a significant interaction between conditioning day and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment [F(2, 62) = 5.394; P < 0.01]. In addition, there was a significant effect of conditioning day [F(2, 62) = 19.31; P < 0.0001], whereas the overall effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment was not significant [F(1, 62) = 1.469; P = 0.2346]. Post hoc analysis revealed no significant difference in the percentage of freezing behaviors on the first (acquisition) or third (extinction) phases, but did show a significant effect on day 2 (recall phase) of the test. Upon subdividing the analysis into the component freezing bouts, it was revealed that these differences are due to the significantly higher percentage of freezing behaviors of L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice during cue sessions 5 (P < 0.01) and 6 (P < 0.05) and context session 6 (P < 0.05) in comparison with broth-fed mice (Fig. 1B).

Regarding depression-related behavior, the forced swim test (FST) analysis revealed that L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed animals spent significantly less time immobile, compared with broth-fed mice (t = 3.926, df = 14; P < 0.01; Fig. 1A).

Effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) Administration on Stress-Induced Corticosterone Levels.

There was a significant interaction between acute stress and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment [F(1, 28) = 7.425; P = 0.011], a significant effect of acute stress [F(1, 28) = 73.90; P < 0.0001] and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment [F(1, 28) = 11.409; P = 0.0022] on corticosterone levels. Post hoc analysis showed that the levels of stress-induced corticosterone are significantly lower in stressed mice that received L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (P < 0.001) than the levels of the hormone in stressed broth-fed mice (Fig. 1C).

Effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on GABA Receptor Expression.

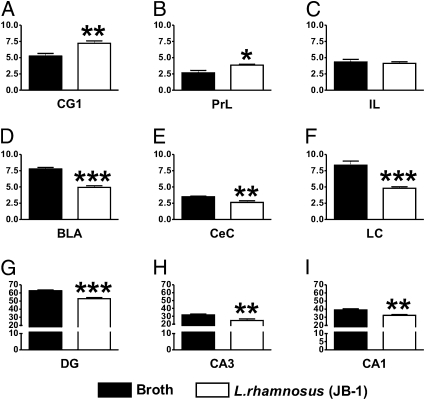

GABAB1b mRNA.

There was a differential expression of this transcript in the different studied areas. Higher levels of GABAB1b mRNA were found in cingulate cortex 1 (CG1) (Fig. 2A) and prelimbic (PrL) (Fig. 2B) cortical areas of L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice in comparison with broth-fed mice (t = 3.485, df = 10, P < 0.01; and t = 2.965, df = 10, P < 0.05, respectively), but no differences were observed in the infralimbic (IL) cortex (t = 0.4558, df = 10, P = 0.658; Fig. 2C). Conversely, L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice had lower levels of GABAB1b mRNA in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) (t = 8.778, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 2D) and central amygdala (CeA) (t = 3.372, df = 10, P < 0.01; Fig. 2E), locus coeruleus (LC) (t = 5.339, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 2F), hippocampal sub areas of the dentate gyrus (DG) (t = 5.555, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 2G), cornus ammonis area 3 (CA3) (t = 3.207, df = 10, P < 0.01; Fig. 2H), and cornus ammonis area 1 (CA1) (t = 3.826, df = 10, P < 0.01; Fig. 2I) compared with broth-fed control mice.

Fig. 2.

Effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration on central GABAB1b mRNA expression. Mice fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (n = 6) had higher levels of GABAB1b mRNA in the cingulate 1 (CG1) (A) and prelimbic (PrL) (B) cortices in comparison with broth fed control mice (n = 6). However, no differences between the two groups were observed in the infralimbic (IL) cortex (C). On the other hand, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) fed animals showed reduced levels of GABAB1b mRNA in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) (D), central amygdala (CeA) (E), locus coeruleus (LC) (F), dentate gyrus (DG) (G), cornus ammonis region 3 (CA3) (H), and cornus ammonis region 1 (CA1) (I) in comparison with broth fed mice. Values represent pixel density (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

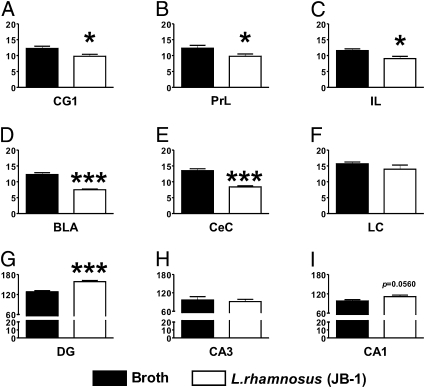

GABAAα2 mRNA.

A differential expression of GABAAα2 mRNA within the studied areas was also found (Fig. 3). In L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed animals, there were low levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in CG1 (t = 2.611, df = 10, P < 0.05; Fig. 3A), PrL (t = 2.267, df = 10, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B), and IL (t = 2.803, df = 10, P < 0.05; Fig. 3C) cortical areas, as well as in the BLA (t = 7.541, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 3D) and CeA (t = 7.150, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 3E), in comparison with broth-fed mice. In addition, no differences in GABAAα2 mRNA were found in the LC between the two groups of mice (t = 1.190, df = 10, P = 0.2616; Fig. 3F); however, higher levels of GABAAα2 mRNA were found in the DG of L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice in comparison with broth-fed control animals (t = 5.967, df = 10, P < 0.001; Fig. 3G). No differences in GABAAα2 mRNA were found in CA3 (t = 0.403, df = 10, P = 0.6955; Fig. 3H) and CA1 (t = 2.161, df = 10, P = 0.0560; Fig. 3I) neuronal layer of the hippocampus of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) compared with broth-fed mice.

Fig. 3.

Effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration on central GABAAα2 mRNA expression. Mice fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (n = 6) had lower levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in CG1 (A) PrL (B), and IL (C) cortices. In addition, GABAAα2 mRNA was also reduced in the BLA (D) and CeA (E) of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) fed mice in comparison with broth fed animals. No differences in GABAAα2 mRNA between the two groups were observed in the LC (F). On the contrary, GABAAα2 mRNA is increased in the DG (G) of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) fed animals in comparison with broth control mice, but no differences were observed in CA3 (H) and CA1 (I). Values represent pixel density (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

Effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) Administration on the Behavior of Vagotomized Mice.

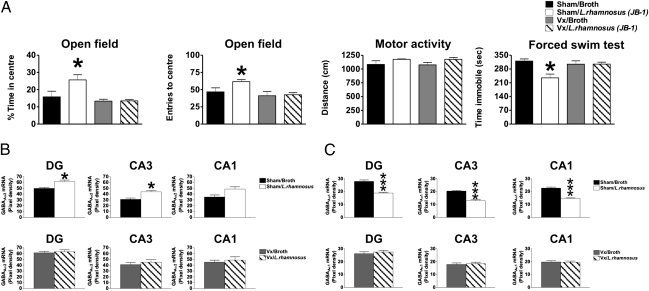

To further understand the role of the vagus nerve in communicating sensory information to the brain, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy (Vx) was carried out, and behavioral parameters were determined. As shown in Fig. 4A, two-way ANOVA revealed that there was an overall effect of Vx [F(1, 36) = 8.91; P < 0.01], an overall effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment [F(1, 36) = 5.80; P < 0.05], and an interaction between Vx and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) [F(1, 36) = 5.690; P < 0.05]. In terms of time in the center of the open field arena, Vx prevented the anxiolytic effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) in mice, which is reflected in a reduction of the time spent in the center of the open field compared with sham surgery animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (P < 0.05). That Vx prevented the anxiolytic effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) is further verified because the analysis of the number entries to the central area of the open field reflects a similar profile as in the percentage of time spent in the central part of the arena [Fig. 6A; effect of Vx: F(1, 36) = 5.56, P < 0.05; effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1): F(1, 36) = 4.64, P < 0.05; interaction between Vx and L. rhamnosus (JB-1): F(1, 36) = 7.66, P < 0.01]. This exploratory behavior seems to be related to an anxiolytic effect, because the total distance traveled by the mice in each experimental condition did not differ between them [F(1, 36) = 0.44, P = 0.51; Fig. 4A].

Fig. 4.

Effect of vagotomy (Vx) on anxiety and depression-like behaviors and GABAA subunit expression of animals treated with L. rhamnosus (JB-1). (A) Sham/L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treated mice (n = 10) (white bars) spent more time in the central area of an open field arena in comparison with sham/broth animals (n = 10) (black bars). This behavior is reflected in the number of entries into the central area of the open field with sham/L. rhamnosus (JB-1) mice (n = 10) performing significantly more entries into this area than sham/broth treated animals. These behaviors are prevented by Vx. These differences are not due to an effect on locomotion, as the distance travelled within the open field is no different between the experimental groups. In the FST sham/L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (n = 10) mice spent less time immobile than sham/broth animals (n = 10) an effect prevented by Vx. (B) Sham/L. rhamnosus (JB-1) mice (n = 6) have significantly higher levels of GABAAα2 mRNA expression in the DG and CA3 areas in comparison with sham/broth animals (n = 6). No significant differences were observed in CA1 between the same experimental groups. Vx prevented any further effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on hippocampal GABAAα2 mRNA expression in the DG CA3 and CA1. (C) Sham/L. rhamnosus (JB-1) (n = 6) mice have significantly lower levels of GABAAα1 mRNA in the DG, CA3, and CA1 in comparison with sham/broth (n = 6) animals. Vx prevented any effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on hippocampal GABAAα1 mRNA expression in the DG, CA3, and CA1 areas in the two experimental groups. (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

In addition, FST revealed that there was an overall effect of Vx [F(1, 36) = 5.14, P < 0.05], an overall effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment [F(1, 36) = 10.47, P = 0.01], and an interaction between Vx and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) [F(1, 36) = 6.22, P < 0.05] in terms of immobility time. Post hoc analysis showed that sham animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) had significantly lower mobility time (P < 0.05) compared with sham animals fed with broth (Fig. 4A). This effect was prevented by Vx, because immobility time of Vx animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) was similar to the immobility time of control mice (P > 0.05).

Effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) Administration on GABA Receptor mRNA Expression: Role of Vagus Nerve.

In our first series of studies, we showed that administration of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) for 28 d had marked and distinct effects on the expression of transcripts for GABAB1b and GABAAα2 receptors subunits in prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and LC compared with broth-fed animals. These findings suggest that the behavioral changes observed could be due to the effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on brain mRNA expression. Thus, to elucidate a mechanistic means as to how L. rhamnosus (JB-1) can affect GABA receptor mRNA expression, in situ hybridization of the two major GABAA receptor subunits was performed in the brains of Vx mice.

GABAAα2 mRNA.

Statistical analysis revealed that there is a significant interaction between L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment and Vx on GABAAα2 mRNA levels [F(1, 20) = 5.674, P = 0.0273] in the BLA and also in the CeA [F(1, 20) = 4.756, P = 0.0413]. There is also an effect of Vx in both areas [BLA: F(1, 20) = 8.532, P = 0.0084; CeA: F(1, 20) = 4.84, P = 0.0397] and an effect of treatment only in the BLA [F(1, 20) = 12.75, P = 0.0019], but not in the CeA [F(1, 20) = 3.586, P = 0.0728; Fig. S1]. Post hoc analysis found that in sham animals, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) significantly reduced the levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in the BLA (P < 0.001) and CeA (P < 0.05) areas of the amygdala in comparison with sham animals fed with broth (Fig. S1 A and B), which is consistent with our initial findings (Fig. 3 D and E). This effect on the GABAAα2 transcript was completely prevented by Vx (Fig. S1 C and D).

In the hippocampus, ANOVA revealed that there was no interaction between L. rhamnosus (JB-1) and Vx on the levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in any of the studied areas [DG: F(1, 20) = 3.47, P = 0.0772; CA3: F(1, 20) = 1.84, P = 0.1900; CA1: F(1, 20) = 1.51, P = 0.2327]. However, it did show an effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) in the DG [F(1, 20) = 6.36, P = 0.02038] and also in CA3 [F(1, 20) = 6.66, P = 0.0179], but not in CA1 [F(1, 20) = 4.13, P = 0.0557]. Additionally, an effect of Vx was only observed in the DG [F(1, 20) = 5.86, P = 0.0248], but not in CA3 [F(1, 20) = 3.09, P = 0.0941] or CA1 [F(1, 20) = 1.47, P = 0.2393]. Post hoc analysis showed that sham animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) had significantly higher levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in the DG (P < 0.05) and CA3 (P < 0.05; Fig. 4B), in comparison with sham animals fed with broth. Vx in broth-fed animals increased the levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in the different hippocampal areas, while L. rhamnosus (JB-1) did not affect the action of Vx on the hippocampus (Fig. 4B; representative images in Fig. S2).

GABAAα1 mRNA.

Densitometric analysis of GABAAα1 mRNA showed an interaction between Vx and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment in both studied areas of the amygdala [BLA: F(1, 20) = 33.43, P < 0.0001; CeA: F(1, 20) = 15.19, P = 0.0009; Fig. S3]. This analysis revealed an effect of Vx on GABAAα1 mRNA [BLA: F(1, 20) = 49.80, P < 0.0001; CeA: F(1, 20) = 73.91, P < 0.0001) and an effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration on this same transcript [BLA: F(1, 20) = 44.53, P < 0.0001; CeA: F(1, 20) = 12.77, P = 0.0019). Post hoc analysis showed that animals that had sham Vx surgery and were fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) showed significant reduction in GABAAα1 mRNA in the BLA (P < 0.0001; Fig. S3A) and CeA (P < 0.0001; Fig. S3B), in comparison with sham animals fed with broth. In addition, no differences in GABAAα1 mRNA were found in L. rhamnosus (JB-1) or broth-fed Vx animals compared with sham control mice.

In the hippocampus, analysis of the levels of GABAAα1 mRNA revealed an interaction between Vx and L. rhamnosus (JB-1) treatment in all studied areas [DG: F(1, 20) = 21.80, P = 0.0001; CA3: F(1, 20) = 19.133, P = 0.0003; CA1: F(1, 20) = 22.87, P = 0.0001; Fig. 4C]. In addition, an effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) was observed in the DG [F(1, 20) = 12.49, P = 0.0021], CA3 [F(1, 20) = 13.49, P = 0.0015], and in CA1 [F(1, 20) = 25.66, P < 0.0001]. However, an effect of Vx was only observed in the DG [F(1, 20) = 9.751, P = 0.0054], but not in the CA3 [F(1, 20) = 2.357, P = 0.1404] or CA1 [F(1, 20) = 1.28, P = 0.2713]. Post hoc analysis found significant reductions in GABAAα1 mRNA in the DG (P < 0.0001), CA3 (P < 0.0001), and CA1 (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4C) in comparison with sham control animals only fed with broth. Vx did not affect the expression of GABAAα1 mRNA in broth-fed animals, and it prevented the effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on GABAAα1 mRNA expression in the analyzed areas (Fig. 4C; representative images in Fig. S4).

Discussion

These data demonstrate specific, previously undescribed neurochemical changes induced by modulation of intestinal microbiota using a potential probiotic [L. rhamnosus (JB-1)] in normal, healthy animals (Table S1). Moreover, we show that L. rhamnosus (JB-1) can have a direct effect upon associated behavioral and physiological responses in a manner that is dependent on the vagus nerve. L. rhamnosus (JB-1) consistently modulated GABAAα2, GABAAα1, and GABAB1b receptor mRNA expression—receptors implicated in anxiety behavior—in a regional-dependent manner.

Furthermore, in this study we observed that L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration reduces the stress-induced elevation in corticosterone, suggesting that the impact of the Lactobacillus on the CNS has an important effect at a physiological level. Alterations in the HPA axis have been linked to the development of mood disorders and have been shown to affect the composition of the microbiota in rodents (26). Our data are in line with previous studies showing that subchronic or chronic treatment with antidepressants can prevent forced swim stress-induced increases in plasma corticosterone in both mice and rats (27). Moreover, it has been shown that alterations in HPA axis modulation can be reversed by treatment with Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (28, 29). However, caution is needed when extrapolating from single timepoint neuroendocrine studies (30). Nonetheless, these data clearly indicate that in the bidirectional communication between the brain and the gut, the HPA axis is a key component that can be affected by changes in the enteric microbiota.

Accumulating evidence suggests that metabotropic GABA receptors are crucial for the maintenance of normal behavior. Indeed, genetic and pharmacological studies have implicated that GABAB receptors play a key role in mood and anxiety disorders (13). In the present study, the mRNA of the GABAB1b subunit, the main isoform of the GABAB1 receptor in the adult brain (13), was increased in the prefrontal cortex of L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed animals. Studies have shown that animal models of depression have reductions in GABAB receptor expression in frontal cortices (13). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the changes induced by the Lactobacillus might provide an advantage toward stressful situations in comparison with broth-fed control animals. This difference is consistent with behavioral and neuroendocrine responses seen. In the other analyzed areas (amygdala, hippocampus, and LC), L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration reduced the expression of GABAB1b mRNA, which is consistent with the antidepressant-like effect of GABAB receptor antagonists (31). L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed animals showed an enhanced memory to an aversive cue and context in comparison with broth-fed mice—an observation that implies changes at the level of the amygdala and hippocampus (24). These findings are consistent with data generated from GABAB1b-deficient animals, highlighting an important role for this subunit in the development of cognitive processes, including those relevant to fear (32, 33). In line with these results, it has recently been shown that treatment with certain bacteria improves memory function in infected mice (34) as well as cognitive abilities in humans (35). However, unlike GABAB1b knockout mice (36), L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice are able to extinguish learned fear, behaviors dependent on the PrL cortex (37), which may reflect the actual up-regulation of this receptor subunit in this brain region.

The amygdala is crucial for manifestation of fear and anxiety responses and for modulation of the affective components of visceral perception. Given increased levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in the amygdala are found in stressed animals (38), the reductions in GABA receptor subunits induced by the Lactobacillus suggest that this bacteria could have promoted an adaptive advantage over broth-fed animals in terms of interaction with stressful situations. The amygdala is also necessary for conditioning of a relatively simple stimulus or cue (conditioned stimulus) and the context in which the unconditioned stimulus is delivered (24, 25). Component analysis revealed that animals fed with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) had significantly higher freezing behaviors during the last cues and context in the second day (recall phase) of testing than broth-fed animals—an observation that is in line with previous reports on BALB/c mice (24). Interestingly, it has been shown that alterations in the expression of GABAA receptor subunits affect fear-related behaviors, as genetic ablation of the GABAAα1 subunit in mice enhances freezing behavior (39). It is worth noting that this increased emotional learning may also be interpreted as increased anxiety behavior; this interpretation suggests that L. rhamnosus (JB-1) has differential effects on conditioned compared with unconditioned aspects of anxiety.

GABAergic neurotransmission in the hippocampus has been related to the modulation of behavior and memory processes (40). Additionally, this structure is required for contextual conditioning, and evidence suggest that inactivation of hippocampal GABAB receptors improves spatial working memory (41). In the present study, hippocampal GABAB1b mRNA is reduced in L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice, which is consistent with an enhanced memory consolidation in the fear conditioning test and further suggests that the changes in hippocampal gene expression induced by the Lactobacillus could in part account for these differences in behavior. L. rhamnosus (JB-1) administration also affected the transcripts of GABAA receptor subunits in the hippocampus. Although differences in the expression of the transcript for GABAAα2 and GABAAα1 have been found in the hippocampus of rats subjected to different learning tasks, these changes are not consistent (38, 42). Nevertheless, it has been shown that GABAA receptors bearing the GABAAα2 subunit mediate the anxiolytic effects of benzodiazepines, whereas GABAA receptors that have the α1 subunit mediate the sedative and amnesic effects of benzodiazepines (12). In the present study, the difference in hippocampal expression of GABAAα2 and GABAAα1 mRNAs support the behavioral findings because L. rhamnosus (JB-1)-fed mice were less anxious and displayed antidepressant-like behaviors in comparison with broth-fed controls. Furthermore, it can be suggested that the effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on fear-related behavior could be due to its effects on stress-induced corticosterone levels. Administration of corticosterone to BALB/c mice after the acquisition phase (day 1) destabilizes fear memory consolidation and allows faster extinction (24), suggesting a mechanism by which corticosterone itself could directly affect fear-related behavior. In the present work, L. rhamnosus (JB-1) reduced the stress-induced levels of corticosterone, which suggest that these “lower” levels could underlie the behavioral alterations observed.

The vagus nerve plays a major role in communicating changes in the gastrointestinal tract to the CNS (3). In the present study, Vx prevented the anxiolytic and antidepressant effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) and also the changes in GABAAα2 and GABAAα1 mRNAs in the amygdala (SI Materials and Methods), as well as GABAAα1 mRNA in the hippocampus. Nevertheless, Vx on its own was able to increase the levels of GABAAα2 mRNA in the hippocampus, although it prevented any further effect produced by L. rhamnosus (JB-1) supporting the observation that the changes in the hippocampus could reflect an indirect consequence of the Lactobacillus-induced changes in structures receiving direct visceral sensory inputs that can project afferents toward the hippocampus. Indeed, it has been shown that vagus nerve stimulation in rats can affect hippocampal functions (43), and therefore the changes in hippocampal GABAAα2 mRNA expression could occur as a result of Vx. Moreover, vagus nerve stimulation has been described as a successful approach to treat some (44), but not all (45), patients with treatment-resistant depression, which further suggests the importance of the vagus nerve in the modulation of behavior. We cannot exclude the possibility that there are physiological changes in the gut associated with Vx that may indirectly alter functional aspects of the Lactobacillus. However, feeding and weight gain were similar in vagotomized and sham-treated animals, and we have previously demonstrated that the ability of this organism to protect against colitis in a murine model is not influenced by subdiaphragmatic Vx (46)—a strong indication that local intestinal anti-inflammatory actions are not altered. The molecular mechanisms underlying how the bacteria affects vagal afferents needs to be resolved in future studies.

One of the important aspects of these studies is that the behavioral changes observed were consistent across two different laboratories using slightly different protocols, which is important, given the perceived problems in replication of behavioral data between laboratories (47). It is important to note that the present neurochemical observations only represent changes at the mRNA level, and not protein, and they could only represent a more complex situation involving other neurotransmitter systems (48) and a variety of intracellular cascades that can affect the expression of these transcripts in the different studied areas. Moreover, probiotic effects are strain dependent; for example, in contrast to L. rhamnosus (JB-1), Lactobacillus salivarius had no neurally dependent effects on murine gut smooth muscle contractions indicating the unlikelihood of L. salivarius having an effect on the enteric nervous system, which must occur before the signals are communicated via the vagus nerve to the brain (21). Considerable further investigation needs to be conducted to the molecular mechanisms at a microbiome level underlying the effects observed. Moreover, future studies using dead bacteria, killed in such a way as to exclude structural alteration, are needed to further insight into the mechanism of action of these bacteria (19, 21). Nonetheless, our data conclusively demonstrate that a potential probiotic can robustly alter brain neurochemistry and behavior relevant to anxiety- and depression-related behavior in mice.

In summary, our data with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) suggest that nonpathogenic bacteria can modulate the GABAergic system in mice and therefore may have beneficial effects in the treatment of depression and anxiety. Moreover, it is worth noting that, in the present study, the effects were observed in healthy animals, whereas most studies examining the effects of potential probiotics on microbiome–gut–brain axis function rely on using infected, germ-free, or antibiotic-treated animals (2, 14); thus, the ramifications of these findings is manifold for the therapeutic potential of bacteria in modulating brain and behavior. Changes in transcripts for GABA receptor subunits emphasize a possible mechanistic insight into the potential effect of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on anxiety-like behavior (12, 13). However, the participation of other neurotransmitter and neuropeptide systems that are of relevance to stress-related psychiatric disorders—such as 5-hydroxytryptamine, norepinephrine, glutamate, and corticotrophin-releasing factor—cannot be ruled out. Thus, future studies should investigate whether chronic treatment with L. rhamnosus (JB-1) can modulate such systems and, if so, how long such changes may last. Furthermore, the effects of L. rhamnosus (JB-1) on neurotransmitter levels are probably downstream of the effects on the HPA axis. In addition, the vagus nerve is responsible for some of the behavioral and molecular changes induced by L. rhamnosus (JB-1), demonstrating a clear pathway for the functional communication between bacteria, the gut, and the brain that modulates the behavioral responses toward different stressful situations. It is worth noting that the majority of studies on the microbiome–gut–brain axis are rodent-based, and future validation of the role of this axis in modulation in behavior is now warranted. Nonetheless, our current studies offer the intriguing opportunity of developing unique microbial-based strategies for the adjunctive treatment of stress-related psychiatric disorders.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Adult male BALB/c mice (n = 36) were used and maintained as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Bacterial Preparation and Strain Designation.

See SI Materials and Methods for further details.

Treatments and Sacrifice.

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the protocols approved by the Ethics Committee, University College Cork under a license issued from the Department of Health and Children [Cruelty to Animal Act 1876, Directive for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (89/609/EEC)]. Experiments conducted in Canada were similarly approved by the Animal Ethics committee of McMaster University. See SI Materials and Methods for further details.

In Situ Hybridization.

The in situ hybridization was conducted as described (48) and as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Behavioral Testing.

Open field test, SIH, EPM, fear conditioning (contextual and cued), and FST were carried out as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Corticosterone Determination.

Plasma corticosterone concentration was determined with a Correlate-EIA enzyme immunoassay kit (Assay Designs) according to manufacturer's instructions. The detection range of this method is from 32 to 20,000 pg/mL.

Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed with a two-tailed Student's t test or two-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was accepted at the level P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lu Wang for performing the vagotomy experiments. This work was supported by the McMaster Integrative Neuroscience Discovery and Study Programme (MiNDS), the Giovanni and Concetta Guglietti Family Foundation, Abbott Nutrition, and St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton. The Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre is funded by Science Foundation Ireland Grants 02/CE/B124 and 07/CE/B1368.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1102999108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bercik P, et al. Chronic gastrointestinal inflammation induces anxiety-like behavior and alters central nervous system biochemistry in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2102–2112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cryan JF, O'Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: From bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:187–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsythe P, Sudo N, Dinan T, Taylor VH, Bienenstock J. Mood and gut feelings. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee SH, Pothoulakis C, Mayer EA. Principles and clinical implications of the brain-gut-enteric microbiota axis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:306–314. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousseaux C, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus modulates intestinal pain and induces opioid and cannabinoid receptors. Nat Med. 2007;13:35–37. doi: 10.1038/nm1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudo N, et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol. 2004;558:263–275. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01620.x. e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heijtz RD, et al. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3047–3052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010529108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyte M, Li W, Opitz N, Gaykema RP, Goehler LE. Induction of anxiety-like behavior in mice during the initial stages of infection with the agent of murine colonic hyperplasia Citrobacter rodentium. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:350–357. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gros DF, Antony MM, McCabe RE, Swinson RP. Frequency and severity of the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome across the anxiety disorders and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goehler LE, et al. Activation in vagal afferents and central autonomic pathways: Early responses to intestinal infection with Campylobacter jejuni. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:334–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudolph U, Möhler H. Analysis of GABAA receptor function and dissection of the pharmacology of benzodiazepines and general anesthetics through mouse genetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;44:475–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cryan JF, Kaupmann K. Don't worry ‘B’ happy!: A role for GABA(B) receptors in anxiety and depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gareau MG, Sherman PM, Walker WA. Probiotics and the gut microbiota in intestinal health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:503–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silk DB, Davis A, Vulevic J, Tzortzis G, Gibson GR. Clinical trial: The effects of a trans-galactooligosaccharide prebiotic on faecal microbiota and symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:508–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao AV, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of a probiotic in emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Gut Pathog. 2009;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma D, Forsythe P, Bienenstock J. Live Lactobacillus reuteri is essential for the inhibitory effect on tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced interleukin-8 expression. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5308–5314. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5308-5314.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karimi K, Inman MD, Bienenstock J, Forsythe P. Lactobacillus reuteri-induced regulatory T cells protect against an allergic airway response in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:186–193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamiya T, et al. Inhibitory effects of Lactobacillus reuteri on visceral pain induced by colorectal distension in Sprague-Dawley rats. Gut. 2006;55:191–196. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma X, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri ingestion prevents hyperexcitability of colonic DRG neurons induced by noxious stimuli. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G868–G875. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90511.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, et al. Luminal administration ex vivo of a live Lactobacillus species moderates mouse jejunal motility within minutes. FASEB J. 2010;24:4078–4088. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vinkers CH, Cryan JF, Olivier B, Groenink L. Elucidating GABAA and GABAB receptor functions in anxiety using the stress-induced hyperthermia paradigm: A review. Open Pharmacol J. 2010;4:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellow S, Chopin P, File SE, Briley M. Validation of open:closed arm entries in an elevated plus-maze as a measure of anxiety in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1985;14:149–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(85)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brinks V, de Kloet ER, Oitzl MS. Corticosterone facilitates extinction of fear memory in BALB/c mice but strengthens cue related fear in C57BL/6 mice. Exp Neurol. 2009;216:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Mahony SM, et al. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: Implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conti AC, Cryan JF, Dalvi A, Lucki I, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is essential for the upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription, but not the behavioral or endocrine responses to antidepressant drugs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3262–3268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03262.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Mahony L, et al. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541–551. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gareau MG, Jury J, MacQueen G, Sherman PM, Perdue MH. Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation. Gut. 2007;56:1522–1528. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.117176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lightman SL, et al. The significance of glucocorticoid pulsatility. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slattery DA, Desrayaud S, Cryan JF. GABAB receptor antagonist-mediated antidepressant-like behavior is serotonin-dependent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:290–296. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacobson LH, Kelly PH, Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Cryan JF. Specific roles of GABA(B(1)) receptor isoforms in cognition. Behav Brain Res. 2007;181:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobson LH, Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Cryan JF. Behavioral evaluation of mice deficient in GABA(B(1)) receptor isoforms in tests of unconditioned anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;190:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0631-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gareau MG, et al. Bacterial infection causes stress-induced memory dysfunction in mice. Gut. 2011;60:307–317. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Messaoudi M, et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:755–764. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobson LH, Kelly PH, Bettler B, Kaupmann K, Cryan JF. GABA(B(1)) receptor isoforms differentially mediate the acquisition and extinction of aversive taste memories. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8800–8803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2076-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Quirk GJ. Sustained conditioned responses in prelimbic prefrontal neurons are correlated with fear expression and extinction failure. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8474–8482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0378-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson-Pick S, Elkobi A, Vander S, Rosenblum K, Richter-Levin G. Juvenile stress-induced alteration of maturation of the GABAA receptor alpha subunit in the rat. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:891–903. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiltgen BJ, et al. The alpha1 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor modulates fear learning and plasticity in the lateral amygdala. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:37. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.037.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crestani F, et al. Decreased GABAA-receptor clustering results in enhanced anxiety and a bias for threat cues. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:833–839. doi: 10.1038/12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Helm KA, et al. GABAB receptor antagonist SGS742 improves spatial memory and reduces protein binding to the cAMP response element (CRE) in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng G, et al. Evidence for a role of GABAA receptor in the acute restraint stress-induced enhancement of spatial memory. Brain Res. 2007;1181:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuo Y, Smith DC, Jensen RA. Vagus nerve stimulation potentiates hippocampal LTP in freely-moving rats. Physiol Behav. 2007;90:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nemeroff CB, et al. VNS therapy in treatment-resistant depression: clinical evidence and putative neurobiological mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1345–1355. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimm S, Bajbouj M. Efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in the treatment of depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:87–92. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Kleij H, O'Mahony C, Shanahan F, O'Mahony L, Bienenstock J. Protective effects of Lactobacillus reuteri and Bifidobacterium infantis in murine models for colitis do not involve the vagus nerve. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1131–R1137. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90434.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crabbe JC, Wahlsten D, Dudek BC. Genetics of mouse behavior: interactions with laboratory environment. Science. 1999;284:1670–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bravo JA, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Alterations in the central CRF system of two different rat models of comorbid depression and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:666–683. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.