The origin of Plasmodium falciparum, the cause of malignant malaria in humans, has been the subject of much debate since closely related parasites were found in (mostly captive) chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas (reviewed in 1). However, analyses of nearly 3,000 fecal samples from wild-living African apes identified P. falciparum-like parasites only in western gorillas (Gorilla gorilla), thus pointing to this species as the original source of human infections (2). Prugnolle et al. (3) have now reported the amplification of P. falciparum-like sequences from the blood of a pet monkey. They propose that this “finding challenges the gorilla origin of the human strains of P. falciparum,” but this conclusion is not justified by the data presented.

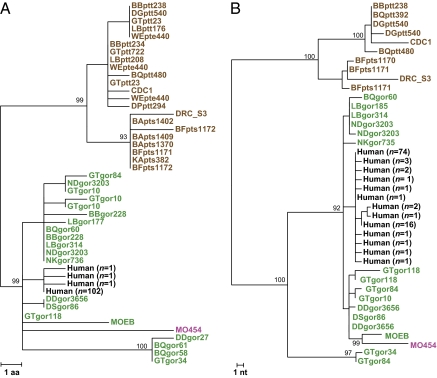

Prugnolle et al. (3) examined blood samples from 338 African monkeys representing 10 different species but were able to amplify P. falciparum-like mtDNA sequences only from one specimen from a greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Thus, although the title of their paper states that “African monkeys are infected by Plasmodium falciparum nonhuman primate-specific strains” (3), in fact, only a single P. falciparum-like strain was identified in a single monkey from a single species. Moreover, the newly identified monkey parasite provided no evidence for their main conclusion that human P. falciparum was as likely derived from monkeys as from gorillas (3). Prugnolle et al. (3) found only 1 of 29 greater spot-nosed monkeys to be Plasmodium-positive. In contrast, western gorillas are infected at high prevalence rates with three Plasmodium species of the Laverania subgenus, one of which is nearly identical to human P. falciparum (2); this species has been shown to infect wild gorillas at 11 different field sites up to 750 km apart (2). Thus, it is clear that western gorillas represent a natural reservoir of this parasite, whereas similar evidence for greater spot-nosed monkeys (or any other monkey species) is lacking. Finally, phylogenetic analyses of over 1,100 mitochondrial, apicoplast, and nuclear gene sequences have shown that all available human P. falciparum sequences are nested within the radiation of gorilla-derived sequences (2), providing compelling evidence for a gorilla origin of human P. falciparum. Inclusion of the new monkey-derived sequence (MO454) does not affect these relationships in any way but, instead, identifies MO454 as a gorilla parasite in a pet monkey (Fig. 1). Thus, the finding of this single infected pet monkey has no bearing on the origin of human P. falciparum.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary relationships among P. falciparum-related parasites from apes, humans, and a monkey. Phylogenetic trees of mitochondrial protein (980 aa; Left) and nonoverlapping nucleotide (2,502 bp; Right) sequences are shown. Only the closest relatives of human P. falciparum (black, numbers indicate sequences per haplotype) from gorillas (green) and chimpanzees (Plasmodium reichenowi, brown) are included; the Plasmodium sequence from a pet monkey (MO454) described by Prugnolle et al. (3) is shown in magenta. The trees were inferred using maximum likelihood methods [as in the study by Liu et al. (2)]. Numbers on branches indicate percentage bootstrap values (only values above 70% are shown). [Scale bars: Left, 1 amino acid (aa) substitution per site; Right, 1 nucleotide (nt) substitution per site.]

Although infections with Laverania parasites appear to be host-specific in the wild (2), human-derived P. falciparum has been detected in captive bonobos (4) and chimpanzees (5), and an apparently gorilla-derived parasite has now been found in a captive monkey (3). Thus, certain ape and human parasites seem capable of infecting new host species when given the opportunity. Further surveys of African primates for Plasmodium infections are clearly warranted, and it will be important to determine the factors that restrict or permit productive transmissions of Plasmodium among different primate species to gauge the prospect of future zoonoses.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Rayner JC, Liu W, Peeters M, Sharp PM, Hahn BH. A plethora of Plasmodium species in wild apes: A source of human infection? Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu W, et al. Origin of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum in gorillas. Nature. 2010;467:420–425. doi: 10.1038/nature09442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prugnolle F, et al. African monkeys are infected by Plasmodium falciparum nonhuman primate-specific strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11948–11953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109368108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krief S, et al. On the diversity of malaria parasites in African apes and the origin of Plasmodium falciparum from Bonobos. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000765. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duval L, et al. African apes as reservoirs of Plasmodium falciparum and the origin and diversification of the Laverania subgenus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10561–10566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]