Abstract

Phospholipase D (PLD) catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylcholine to the lipid second messenger phosphatidic acid. Two mammalian isoforms of PLD have been identified, PLD1 and PLD2, which share 53% sequence identity and are subject to different regulatory mechanisms. Inhibition of PLD enzymatic activity leads to increased cancer cell apoptosis, decreased cancer cell invasion and decreased metastasis of cancer cells; therefore, the development of isoform-specific, PLD inhibitors is a novel approach for the treatment of cancer. Previously, we developed potent dual PLD1/PLD2, PLD1-specific (>1,700-fold selective) and moderately PLD2 preferring (>10-fold preferring) inhibitors. Here, we describe a matrix library strategy that afforded the most potent (PLD2 IC50 = 20 nM) and selective (75-fold selective versus PLD1) PLD2 inhibitor to date, N-(2(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide (22a), with an acceptable DMPK profile. Thus, these new isoform-selective PLD inhibitors will enable researchers to dissect the signaling roles and therapeutic potential of individual PLD isoforms to an unprecedented degree.

Keywords: phospholipase D, PLD, cancer, isoform, allosteric

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality in the United States.1 Both academic and industrial groups have expended significant effort in attempts to develop novel chemotherapeutics and, more recently, to identify previously underappreciated targets essential to disease progression. Advancing our basic understanding of cancer as a molecular phenomenon through the use of small molecules is an important mechanism by which to both identify new targets and develop innovative cancer therapeutics. Historically, targeted cancer drug discovery efforts have focused on the development of small molecule kinase inhibitors (typically at the ATP binding site, though allosteric inhibitors are emerging) due to the central role many kinases play in regulating cell growth and division. The development of kinase inhibitors into drugs has been partially hindered by poor selectivity versus the more than 500 members of the human kinome. The identification of other protein targets that regulate cell survival, invasion and proliferation will provide alternative options for cancer drug development.

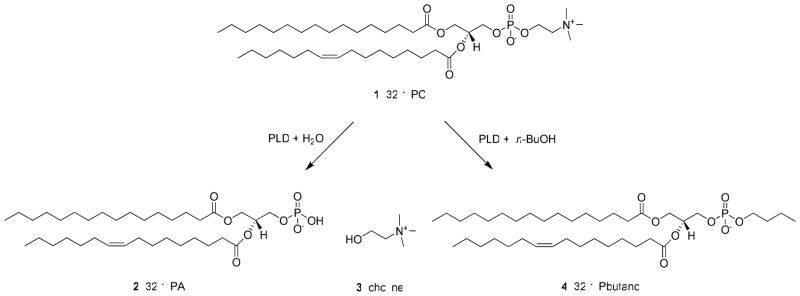

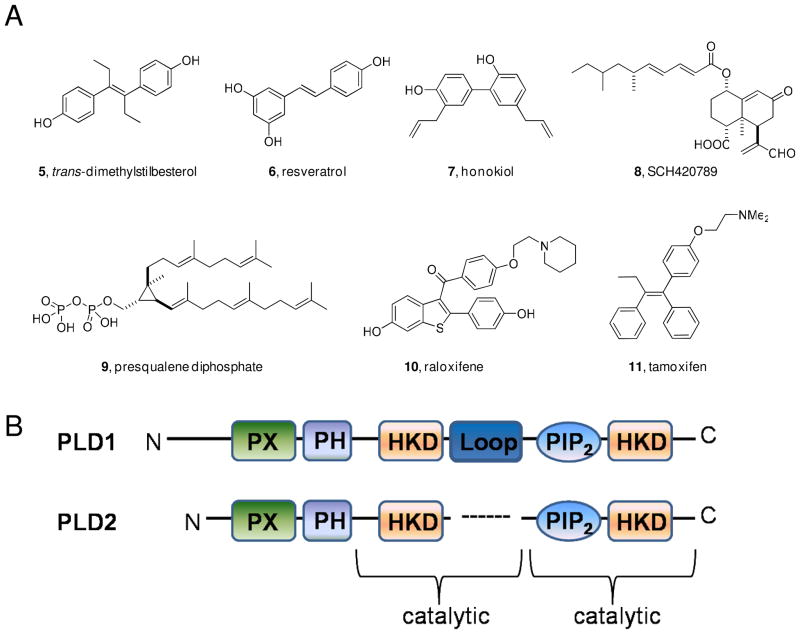

PLD catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine (PC, 1) into the lipid second messenger phosphatidic acid (PA, 2) and choline 3 (Figure 1).2 PA is an essential lipid second messenger that is strategically located at the intersection of several essential signaling and metabolic pathways.3 Increased PLD expression and aberrant PLD enzymatic activity have been observed in a variety of human cancers including breast cancer 4, renal cancer5, colorectal cancer6 and glioblastoma7. Additionally, PLD activity has been shown to be required for mutant Ras driven tumorigenesis in mice. 8 Experiments utilizing inactivating mutations of PLD suggest that inhibiting PLD enzymatic activity decreases cancer cell invasion9 and increases apoptosis10. On a molecular level PLD has been implicated in oncogenic signaling events involving the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)11, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) secretion7, 12, p5313, 14, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) 15, 16 and Ras17. Taken together, evidence from genetic and biochemical experiments indicate that PLD is an attractive target for cancer therapy. Until recently the tools available to inhibit PLD activity were limited to genetic and biochemical approaches including the use of n-butanol, none of which are viable therapeutic options. Furthermore, n-butanol is not a PLD inhibitor, rather n-butanol blocks PLD-catalyzed phosphatidic acid production by competing with water as a nucleophile thereby causing the formation of phosphatidylbutanol 4 in a unique transphosphatidylation reaction.2 Several pan-PLD inhibitors 5–11 have been reported18–24, but many of these compounds do not act directly on the enzyme, lack target potency or are not drug-like molecules (Figure 2A). Developing isoform-selective PLD inhibitors is a formidable task due to several factors: (1) PLD1 and PLD2 are challenging to purify in large quantities, (2) the enzyme activity assays are labor intensive and time consuming (3) the two mammalian isoforms of PLD share 53% sequence identity (Figure 2B). Importantly, due to the multitude of cellular events which require PA ablating all PLD enzymatic activity may not be a viable therapeutic approach, in which case it would be necessary to possess isoform-selective PLD inhibitors.

Figure 1.

PLD catalyzed the hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine 1 (PC) into phosphatidic acid 2 (PA) and choline 3. In the presence of a primary alcohol, typically n-butanol, PLD catalyzes a unique transphosphatidylation reaction to produce phosphatidybutanol 4.

Figure 2.

A) Structures of reported PLD inhibitors; B) Sequence of PLD1 and PLD2 highlighting the PX and PH domains, the two HKD motifs, the two catalytic sites and the loop in PLD1, which is absent in PLD2. Overall, homology between the two PLD isoforms is only 53%.

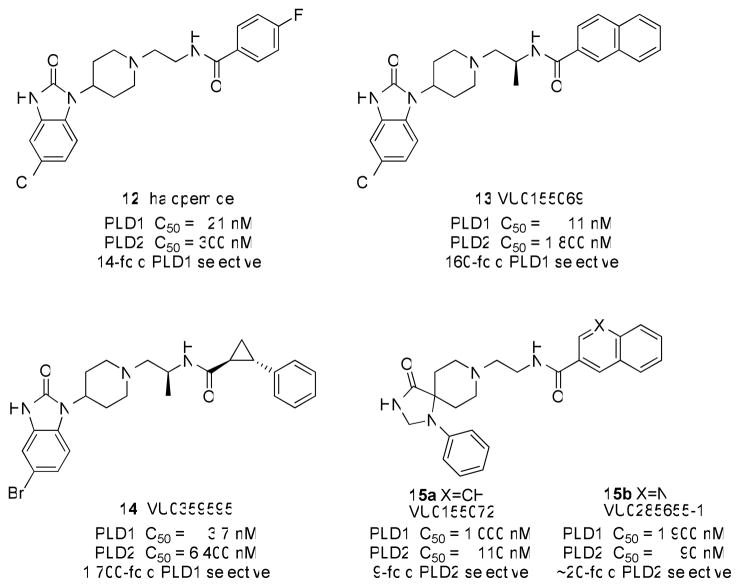

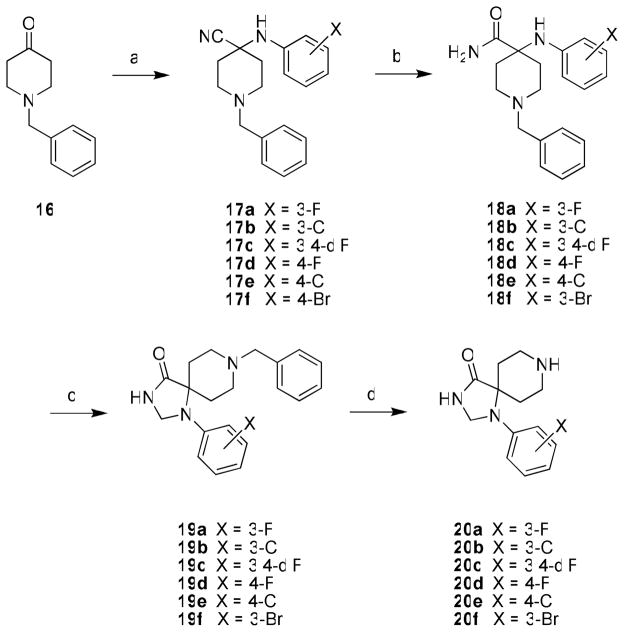

A turning point for the field occurred in 2007, when a group at Novartis disclosed halopemide 12 as a PLD2 inhibitor discovered in a high-throughput screen25; however, rigorous characterization by our labs demonstrated that 12 and the reported analogs were dual PLD1/2 inhibitors or even moderately PLD1-preferring (Figure 3).26 Nonetheless, this was the first time a potent, direct-acting, drug-like, small-molecule PLD inhibitor had been reported, therefore we began a campaign to optimize halopemide for isoform-specific PLD inhibition. An initial diversity-oriented synthesis approach yielded a library of 263 compounds containing direct-acting, potent (IC50 values 1–50 nM) PLD1 inhibitors, such as 13 with 160-fold selectivity versus PLD2 in cellular enzyme activity assays.26 A subsequent iterative analog synthesis approach delivered 14, with improved PLD1 potency (IC50 = 3.7 nM) and selectivity (>1700-fold selective versus PLD2 in cells).27 The identification of a single chiral (S)-methyl group provided a significant gain in PLD1 selectivity. Developing a PLD2 selective inhibitor has been significantly more challenging. After synthesizing over 500 compounds, we identified a 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one scaffold that engendered PLD2 preferring inhibition, with the best compound, 15b, only possessing ~20 fold selectivity for PLD2 in cells (Figure 3).28 Studies with various PLD constructs suggests that these inhibitors may bind at an allosteric site in the N-terminus, accounting for the high isoform selectivity and unique, shallow SAR.26 Moreover, these inhibitors blocked the in vitro invasive migration of a triple negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231), and siRNA studies indicated that PLD2 played a dominant role.26

Figure 3.

Structures and activities of halopemide 12 and isoform-selective PLD inhibitors 13 and 14 (PLD1 selective) and 15a–b (PLD2 preferring).

Due to a lack of small molecule tools and a perception of phospholipases as non-druggable targets coupled with labor intensive and complex assay systems, little effort has been focused on their therapeutic potential. Herein we discuss our ongoing medicinal chemistry efforts to develop isoform-selective phospholipase D (PLD) inhibitors, the development of the first PLD2 selective inhibitor, and the potential for PLD inhibitors as a new class of cancer therapeutics. Here, we report the results of our a matrix library approach to increase PLD2 potency and selectivity within the 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one series.

Chemistry

Previous work showed that SAR was shallow with respect to the Eastern amide moiety in 15a–b28, thus current efforts focused on functionalization of the 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one scaffold by the incorporation of various halogens, as this proved successful in the benzimidazolone-based PLD1 inhibitors 13 and 14.27 Only the unsubstituted 1-phenyl-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one was commercially available, so while known in the literature, the halogenated congeners had to be synthesized. As shown in Scheme 1, N-benzyl piperidinone 16 underwent a Strecker reaction with 3-fluoroaniline to provide 17a, and acidic hydrolysis delivered the carboxamide 18a in 68% yield for the two steps. Closing of the spirocyclic five-membered ring required forcing microwave-assisted conditions (150° C for 15 minutes in AcOH), followed by reduction to provide 19a in 12% yield. A final hydrogenation with Pd/C removed the benzyl protecting group affording the key scaffold 20a in 96% yield. In a similar manner, key scaffolds 20b–f were prepared in overall yields from 16 averaging 8%.

Scheme 1a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) KCN, AcOH, ArNH2, 12 h, rt; (b) H2SO4, 12 h, 68%–74% for two steps; (c) i.) trimethyl orthoformate, AcOH, microwave, 150 °C, 15 min; ii.) NaBH4, MeOH, 3 hr, 12%–20%; (d) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, AcOH, 20 hr, 89–96%.

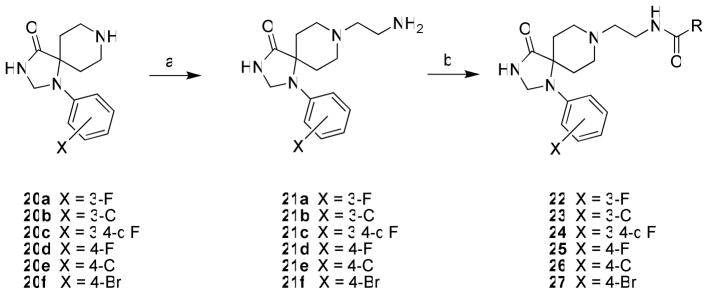

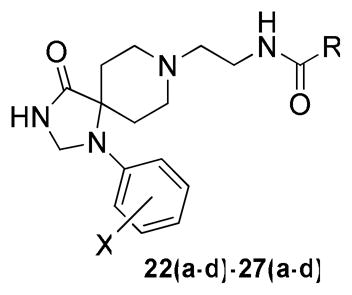

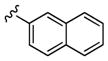

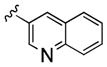

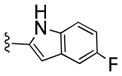

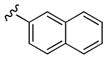

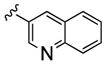

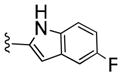

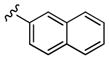

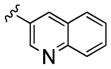

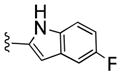

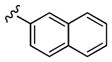

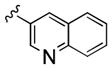

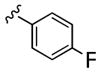

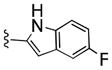

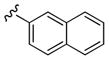

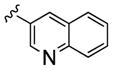

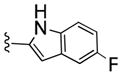

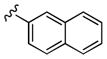

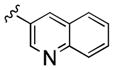

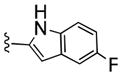

With the requisite synthetically derived halogenated congeners 20a–f in hand, we initiated the synthesis of a 4×6 matrix library of twenty-four analogs based on the PLD2 preferring inhibitors 15a–b (Scheme 2). In the event, 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-ones 20a–f underwent a reductive amination reaction with tert-butyl 2-oxoethylcarbamate to provide, after deprotection, amines 21a–f in 58-78% yields. Then, the six amines 21a–f were acylated with four acid chlorides (2-naphthyl, 3-quinolyl, 4-fluorobenzoyl and 5-fluoro-2-indolyl) to deliver the 24-member library of analogs 22(a–f)-27(a–f) in 75–85% yields. All final compounds were purified by mass-directed preparative HPLC to analytical purity.

Scheme 2a.

aReagents and conditions: 22(a–f) – 27(a–f) (a) i.) tert-butyl 2-oxoethylcarbamate, MP-B(OAc)3H, DCM, MeOH, 18 hr, ii.) 4.0M HCl/dioxane, DCM, MeOH, 4 hr, 58–78%; (b) RCOCl, DIEA, DMF, rt, 4 hr, 75–85%.

Results and Discussion

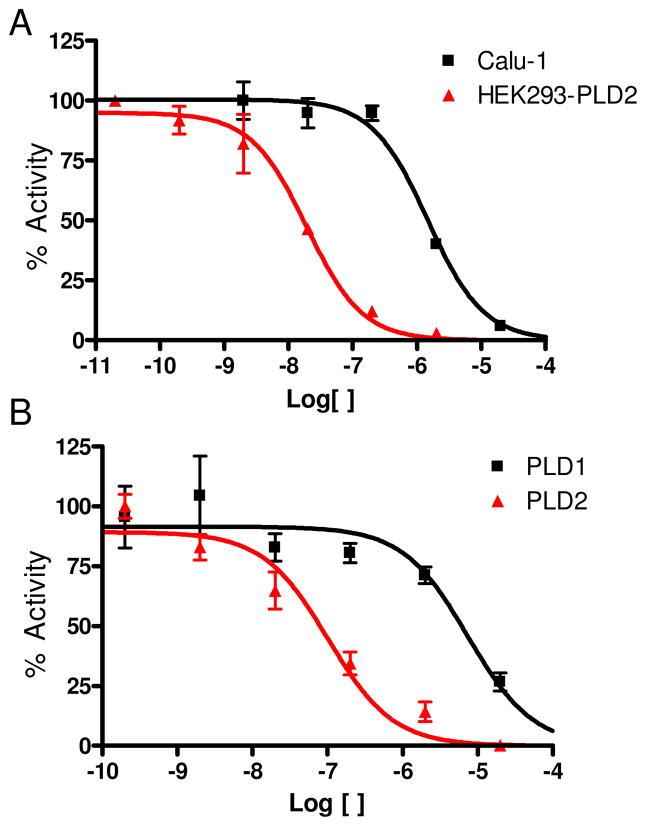

All library members 22(a–d)-27(a–d) were evaluated for their ability to inhibit PLD1 and PLD2 in a cellular assay (Calu-1 and HEK293-gfpPLD2 cell lines, respectively) as well as a biochemical assay with recombinant PLD1 and PLD2 enzymes. The cellular assays were the ‘workhorse’ assays that drove the SAR, with routine confirmation in the in vitro biochemical assay to ensure compounds were direct acting inhibitors. As shown in Table 1, SAR for the 24-member library marked a clear departure from the SAR of the earlier PLD1 selective benzimidazolone-based inhibitors, and all but two of the analogs 22(a–d)-27(a–d) displayed a preference for PLD2 inhibition, with the two exceptions, 26c and 27c, being dual PLD1/2 inhibitors with comparable PLD1 and PLD2 inhibition. Both PLD2 potency and selectivity were dependent on the halogen employed, the substitution pattern on the phenyl ring of the 1,3,8-triazaspiro[4,5]decan-4-one scaffold and on the nature of the eastern amide moiety. As with many allosteric ligands, SAR was shallow and unpredictable. However, this matrix library approach identified several PLD2 inhibitors that represented a significant improvement over the original PLD2 inhibitor 15a, and highlights the power and utility of a matrix library approach, as the SAR would not have informed a singleton approach towards optimal PLD2 inhibitors. For example, 23c and 25b displayed ~50-fold selectivity for PLD2, with PLD2 IC50s of 70 nM and 40 nM, respectively; interestingly, 23c contains the 3-Cl moiety and a 4-fluorphenyl amide whereas 25b is based on a 4-F scaffold and a 3-quinolinyl amide. Any other combination within these scaffolds results in a decrease in either PLD2 potency or PLD2 selectivity. From this effort, we discovered the most potent and selective PLD2 inhibitor to date, 22a (VU0364739), with a PLD2 IC50 of 20 nM and possessing 75-fold selectivity versus PLD1 in the cellular assay (Figure 4A). In our in vitro biochemical assay using purified PLD1 and PLD2, 22a possessed a PLD1 IC50 of 7,500 nM and a PLD2 IC50 of 100 nM, replicating the unprecedented 75-fold selectivity for PLD2 (Figure 4B). While we could not replicate the fortuitous 1,700-fold PLD1 selectivity of 14 in a PLD2 preferring inhibitor, the 75-fold PLD2 selectivity of 22a afforded a small molecule probe to effectively evaluate PLD2 pharmacology. With potent and isoform-selective PLD1 (14) and PLD2 (22a) inhibitors in hand, we were poised to dissect the individual roles of PLD1 and PLD2 in a number of in vitro cancer cell models.

Table 1.

Structures and Cellular Assay Activities of Analogs 22(a–d)-27(a–d).

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmpd | X | R | PLD1 IC50 (nM)a | PLD2 IC50 (nM)b | Fold PLD2 Selective | |

| 22a | 3-F |

|

|

1,500 | 20 | 75 |

| 22b |

|

2,500 | 63 | 40 | ||

| 22c |

|

12,000 | 6 700 | 1 8 | ||

| 22d |

|

210 | 25 | 8 | ||

| 23a | 3-Cl |

|

|

1,200 | 290 | 4 |

| 23b |

|

870 | 165 | 5 | ||

| 23c |

|

3,470 | 70 | 50 | ||

| 23d |

|

250 | 73 | 3 4 | ||

| 24a | 3 4-diF |

|

|

2,800 | 120 | 23 |

| 24b |

|

2,060 | 70 | 30 | ||

| 24c |

|

5,780 | 660 | 9 | ||

| 24d |

|

390 | 100 | 4 | ||

| 25a | 4-F |

|

|

1,700 | 80 | 21 |

| 25b |

|

2,000 | 40 | 50 | ||

| 25c |

|

14,000 | 610 | 23 | ||

| 25d |

|

290 | 30 | 9 | ||

| 26a | 4-Cl |

|

|

2,270 | 655 | 3 5 |

| 26b |

|

3,500 | 200 | 17 | ||

| 26c |

|

5,590 | 5 670 | ~1 | ||

| 26d |

|

335 | 50 | 7 | ||

| 27a | 4-Br |

|

|

5,900 | 350 | 17 |

| 27b |

|

2,700 | 360 | 8 | ||

| 27c |

|

10,000 | 8000 | ~1 | ||

| 27d |

|

2,660 | 100 | 27 | ||

Cellular PLD1 assay with Calu-1 cells.

Cellular assay with HEK293-gfp PLD2 cells. Cell based assays were used to develop CRCs (from 200 pM to 20 uM) and determine IC50S for all compounds in Calu-1 or HEK293-gfpPLD2 cell lines. The geometric mean of the standard errors of the log (IC50) values from the curve fits of all compounds were computed and compared to the IC50S themselves There were levels of ~30% error for Calu-1 and ~70% for HEK293-gfpPLD2 IC50S. Despite the variance in the absolute values over a large number of assays, the reproducibility of the effects and relative potency of the inhibitors were found to be robust.

Figure 4.

Concentration-Response-Curves (CRCs) for A) cellular PLD1 ■ (Calu-1) assay and PLD2

(HEK293-gfpPLD2) assay and B) biochemical inhibition assay CRCs with purified ■ PLD1 and

(HEK293-gfpPLD2) assay and B) biochemical inhibition assay CRCs with purified ■ PLD1 and

PLD2 highlighting the unprecedented 75-fold PLD2 versus PLD1 selectivity for 22a in both PLD assays. Error bars show standard error of the mean for triplicate measurements.

PLD2 highlighting the unprecedented 75-fold PLD2 versus PLD1 selectivity for 22a in both PLD assays. Error bars show standard error of the mean for triplicate measurements.

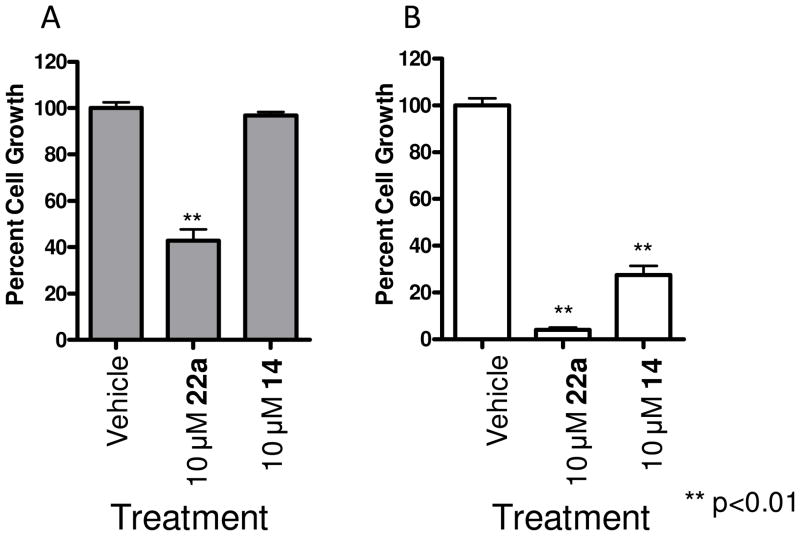

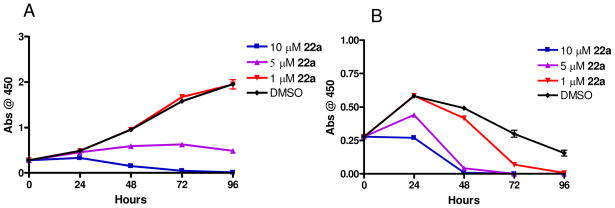

In our earlier work with PLD1 inhibitor 13 and the moderately selective PLD2 inhibitor 15a, we found that both inhibitors blocked the in vitro invasive migration of a triple negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231); however, siRNA studies indicated that PLD2 played a dominant role.26 With significantly improved isoform-selective PLD1 (14) and PLD2 (22a) inhibitors, we extended our study to dissect the roles of PLD1 and PLD2 for proliferation and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. PLD2 inhibitor 22a provided a striking effect in a 48 hour cell proliferation assay, wherein inhibition of PLD2 affords a pronounced decrease in cell proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells, as compared to an equivalent 10 μM concentration of the PLD1 inhibitor 14 (Figure 5A). When cultured under serum free conditions, the same assay in MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in almost a complete blockade of proliferation with 22a, and under these conditions, PLD1 inhibition has a significant effect as well (Figure 5B). These data do show a preferential sensitization of MDA-MB-231 cells to PLD2 inhibition. There was a noticeable difference in the effect of PLD inhibitor treatment on MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation depending on culture conditions. When cells were cultured in the absence of serum with either inhibitor 14 or 22a there was a more pronounced decrease in cell growth compared to the vehicle control samples or those cells cultured in the presences of 10% FBS. There are several possible explanations for this observation. This data may suggest that when these cells undergo the stress of serum depravation survival pathways in which PLD is key component become essential for cell proliferation and the inhibition of the PLD enzymatic activity causes a decrease in cell proliferation. Alternatively, the pharmacokinetic properties, specifically plasma protein binding, of these small-molecules have not been optimized, and it is likely that a significant percentage of the compound in experiments containing 10% FBS will be serum protein bound. We then evaluated the effect of 22a on cell proliferation in MDA-MB-231 cells over a 96 hour time course and with a dose-response paradigm (Figure 6). In the presence of 10% FBS, 22a displayed a dose-dependent decrease in cell proliferation over the time course, with significant effects at both a 5 μM and 10 μM dose (Figure 6A). Under serum free conditions (Figure 6B), a more pronounced effect was observed in a dose (1 μM, 5 μM and 10 μM) and time dependent manner, again suggesting that PLD may be playing a role in the stress response of these cells. Importantly, 22a was significantly less cytotoxic in standard cell viability assays in non-transformed cells (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of PLD2 with 22a leads to decreased proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in the presence of PLD inhibitor for 48 hours after which cell viability was assayed using WST-1 cell proliferation reagent. A. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in the presence of 10% FBS were fairly resistant to PLD inhibitor treatment with only 10 μM 22a treatment leading to a significant decrease in cell proliferation. B. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under serum free conditions had a more pronounced response to PLD inhibition with both PLD1 (14) and PLD2 (22a) selective compounds significantly decreasing cell proliferation. n=3. Error bars show standard error of the mean for triplicate measurements.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of PLD2 leads to a time dependent decrease in proliferation of MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in the presence of PLD inhibitor and cell viability was assayed using WST-1 cell proliferation reagent over 96 hours. A. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in the presence of 10% FBS showed a dose dependent attenuation of cell proliferation over time. Cultures with 10 and 5 μM 22a treatment led to a significant decrease in cell proliferation while 1 μM inhibitor had no effect. B. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in the absence of serum had a more pronounced response to PLD inhibition with all concentrations of the PLD2 selective compound significantly decreasing cell proliferation in a dose and time dependent manner. Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars show standard error of the mean for triplicate measurements.

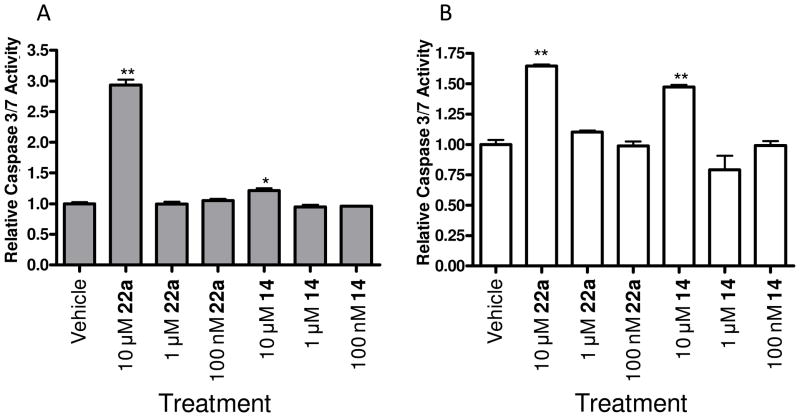

Next, we evaluated the role of PLD1 and PLD2 inhibition on apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 with and without serum, employing Caspase 3 and 7 as a surrogate marker for apoptosis (Figure 7). Once again, our isoform-selective inhibitors were able to distinguish differential roles for PLD1 and PLD2. In the standard 48 hour apoptosis assay, a 10 μM dose of PLD2 inhibitor 22a provided a significant (3-fold increase) increase in Caspase 3 and 7 activity, whereas inhibition of PLD1 with 14 led to a marginal increase in Caspase 3 and 7 activity (Figure 7A). Under serum free conditions, both 14 and 22a had similar effects on Caspase 3 and 7 activity (Figure 7B). These data again suggest that PLD2 signaling plays a critical role in the invasive migration, proliferation and survival of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Moreover, these data were only obtainable once isoform-selective small molecule PLD1 and PLD2 inhibitors were developed.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of PLD2 leads to increased apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells compared with minimal effect of PLD1 inhibition. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in the presence of PLD inhibitor for 48 hours after which time Caspase 3 & 7 activity was measured. A. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured in the presence of 10% FBS were fairly resistant to PLD inhibitor treatment (14 or 22a) with only 10 μM 22a treatment leading to a significant increase in Caspase 3 & 7 activity compared to vehicle control. B. MDA-MB-231 cells cultured under serum free conditions had increased Caspase 3 & 7 activity upon 10 μM PLD inhibitor treatment as compared to the vehicle control. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01. Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars show standard error of the mean for triplicate measurements.

Compounds 14 and 22a were then subjected to a battery of DMPK assays to elucidate their respective disposition characteristics, ultimately in an effort to frame these isoform selective PLD inhibitors as suitable candidates as in vivo probes of PLD function. PLD1 inhibitor 14 was lipophillic (clogP = 4.5), and yet was ~2% free in rat and human plasma protein binding experiments (equilibrium dialysis) with a corresponding ease of formulation into dose vehicles amenable to IV and PO administration. Parenteral administration to rats (n=2) revealed 14 to be a highly cleared compound (CL = 60 mL/min/kg), approaching that of hepatic blood flow (Qh) in the rat (Table 2). A corresponding volume of distribution at steady-state (Vdss) for 14 of 4.7 L/kg produced a mean residence time (MRT) of 1.1 hr and an effective half-life (t1/2) of 0.78 hr in rat. A similar profile was obtained for PLD2 inhibitor 22a. While less lipophilic (clogP = 3.2), 22a also displayed ~2% free fraction in rat and human plasma protein binding experiments (equilibrium dialysis) and was easily formulated into acceptable vehicles. Similarly, parenteral administration to rats revealed 22a to be a highly cleared compound (CL = 61 mL/min/kg), with a high volume of distribution (Vdss = 8.1 L/kg), a 2.2 hr MRT and a corresponding effective t1/2 of 1.5 hr. Employing rat hepatic microsomes, the intrinsic clearance values (CLint, Eq. 1 and 2) for 14 and 22a were determined to be 660 and 203 mL/min/kg, respectively (data not shown) and converted to predicted hepatic clearance (CLhep), utilizing the well-stirred model of hepatic clearance (Eq.3), produced CLhep values of 63 and 52 mL/min/kg. The general agreement between in vitro and in vivo clearance (CL and CLhep) values indicate hepatic metabolism to be a likely mechanism contributing to the disposition of 14 and 22a.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic Profile of 14 and 22a in Rat.

| Cmpd | plasma protein binding (% bound) | IV (pharmacokinetics)a |

PO (plasma & brain levels)b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dose (mg/kg) | CL (mL/min/kg) | t1/2 (h) | Vdss (L/kg) | dose (mg/kg) | Plasma (ng/mL) | Brain (ng/mL) | Brain/Plasma | ||

| 14 | 98.1 | 1 | 60.7 | 0.78 | 4.7 | 10 | 29 | BLQ | BLQ |

| 22a | 97.9 | 1 | 61.5 | 1.52 | 8.1 | 10 | 39.9 | 29 | 0.73 |

20% DMSO/80% saline;

10% tween 80/0.5% methylcellulose

Recent genetic and knock-out studies have suggested therapeutic roles for PLD inhibition in Alzheimer’s disease29,30 and stroke31; therefore, PLD inhibitors with exceptional CNS bioavailability would be of great value for preclinical target validation. To address CNS penetration, fasted Sprague-Dawley rats (n=2) received a single, oral gavage of 14 and 22a at a dose of 10 mg/kg in a typical 90 minute single point brain:plasma (PBL) study design. While levels of 14 were below quantitation in the brain, the napthylene analog 22a displayed a brain:plasma value of 0.73, thereby representing the first centrally penetrant PLD inhibitor. While 14 and 22a remain important in vitro tools to probe and describe the differential roles and pharmacology of PLD1 and PLD2, additional optimization will be required to develop robust in vivo proof-of-concept compounds. These data also suggest that the differences observed in the cellular experiments involving the presence and absence of serum could be due to the lipophillic character of these compounds and the result that ~2% is displayed as free fraction in rat and human plasma protein binding experiments.

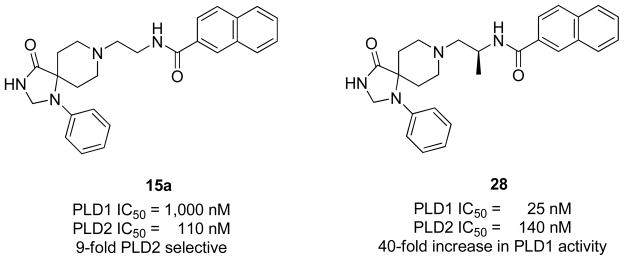

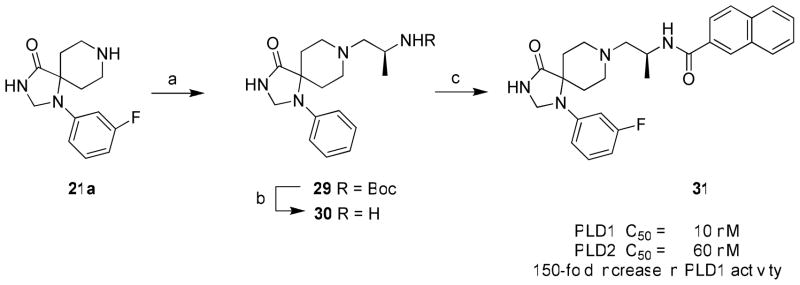

Finally, the impact of incorporating an (S)-methyl group was found to be important for increasing PLD inhibitory activity in the PLD1-selective benzimidazolone series represented by 13 and 14. Installation of the (S)-methyl group into the modestly PLD2-preferring 15a (PLD1 IC50 = 1,000 nM, PLD2 IC50 = 110 nM), within the triazaspirone series (Figure 8), resulted in 28 with enhanced (40-fold) PLD1 inhibition and essentially no effect on PLD2 activity (PLD1 IC50 = 25 nM, PLD2 IC50 = 140 nM).28 This type of ‘molecular switch’ has been noted before for allosteric modulators of GPCRs engendering either subtype selectivity or reversing the mode of pharmacology (NAM to PAM or PAM to NAM). Thus, we wanted to evaluate if the addition of the PLD1-preferring (S)-methyl ‘molecular switch’ would increase PLD1 inhibitory activity in a highly PLD2 preferring compound such as 22a. In the event, 22a underwent a reductive amination with (S)-tert-butyl 1-oxoproan-2-yl carbamate to provide 29, which was then deprotected to provide 30. Acylation with 2-naphthoyl chloride afforded the (S)-methyl analogs 31 of 22a (Scheme 3). Evaluation of 31 in our PLD1 and PLD2 cellular assays (Calu-1 and HEK293-gfpPLD2, respectively) further highlighted the impact of the (S)-methyl group as a ‘molecular switch’ for these allosteric ligands, providing a 150-fold increase in PLD1 inhibitory activity (PLD2 IC50 = 10 nM) while maintaining PLD2 activity (PLD2 IC50 = 60 nM). Thus, a 75-fold PLD2 preferring inhibitor 22a is converted into a potent dual PLD1/2 inhibitor 31 by the addition of a single methyl group.

Figure 8.

Structures and activities of PLD2 preferring inhibitor 15a and impact of a chiral (S)-methyl group providing 28 and a 40-fold increase in PLD inhibitory activity.

Scheme 3a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (S)-tert-butyl 1-oxoproan-2-ylcarbamate, MP-B(OAc)3H, DCM, MeOH, 18 hr, 34% (b) 4.0M HCl/dioxane, DCM, MeOH, 4 hr, 98%; (c) 2-naphthoyl chloride, DIEA, DMF, rt, 4 hr, 9%.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed the most potent (PLD2 IC 50 = 20 nM) and selective (75-fold versus PLD1) PLD2 inhibitor 22a (VU0364739) described. Due to the shallow and unpredictable SAR for these allosteric PLD inhibitors, a matrix library approach enabled the rapid discovery of 22a, whereas a classical singleton approach probably would have failed to discover 22a. As with other allosteric ligand optimization programs, SAR proved to be shallow and somewhat unpredictable for the triazaspirone series, with PLD potency and PLD2 selectivity dependent on both the halogen substituent on the triazaspirone scaffold and the nature of the amide moiety. With potent and selective PLD1 and PLD2 inhibitors in hand, we were able to dissect the relative contributions of PLD1 and PLD2 signaling on proliferation and survival of the triple negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. In all instances, selective PLD2 inhibition with 22a displayed significant effects, and suggests that for this cancer cell line, a PLD2 inhibitor, not a PLD1 or a dual PLD1/2 inhibitor, would be the optimal therapeutic agent. Introduction of a ‘molecular switch’, in the form of an (S)-methyl group, to 22a increased PLD1 activity 150-fold providing a potent PLD1/2 inhibitor 31. Current efforts are focused on employing 14 and 22a to dissect the contributions of PLD1 and PLD2 signaling in other cancer cell lines as well as developing additional isoform-selective PLD inhibitors with improved DMPK properties which will enable the discovery of new indications, such as schizophrenia, stroke and Alzheimer’s disease, where aberrant PLD activity is implicated.

Experimental Section

All reactions were carried out employing standard chemical techniques. Unless otherwise noted, reactions were run in anhydrous solvents. Solvents for extraction, washing and chromatography were HPLC grade. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Biotage at the highest commercial quality and were used without purification. Microwave-assisted reactions were conducted using a Biotage Initiator-60 single mode microwave synthesizer. All NMR spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz Bruker AMX NMR. 1H chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the solvent residual peak (MeOD = 3.31, DMSO-d6 = 2.50, CDCl3 = 7.26). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet), coupling constant (Hz), and integration. 13C chemical shifts are reported as δ values in ppm relative to the solvent residual peak (MeOD = 49.0, DMSO-d6 = 39.5, CDCl3 = 77.16). Low resolution mass spectra were obtained on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with electrospray ionization equipped with a YMC Jsphere H-80 S-4 3.0 × 50 mm column running a gradient of 5–95% (over 4 minutes) acetonitrile in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid in water. Low resolution mass spectra for compounds 30 and 31 were obtained on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with electrospray ionization equipped with a Phenomenex Kinetex 2.1 × 50 mm C18 column running a gradient of 10–95% (over 45 seconds) acetonitrile in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid in water. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Waters QToF-API-US plus Acquity system with electrospray ionization. Analytical thin layer chromatography was performed on 250 μm silica gel 60 F254 plates. Automated flash column chromatography was performed on a Teledyne ISCO combiflash Rf system. Analytical HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1200 analytical LCMS equipped with a YMC Jsphere H-80 S-4 3.0 × 50 mm column running a gradient of 5–95% (at a flow rate of 1.25 mL/min over 4 minutes) acetonitrile in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid in water, and UV detection at 214 nm and 254 nm along with ELSD detection. Analytical HPLC for compounds 30 and 31 was performed on an Agilent 1200 LCMS with electrospray ionization equipped with a Phenomenex Kinetex 2.1 × 50 mm C18 column running a gradient of 10–95% (over 45 seconds) acetonitrile in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid in water, and UV detection at 214 nm and 254 nm. Preparative purification of library compounds was performed on a custom Agilent 1200 preparative LCMS with collection triggered by mass detection or alternatively compounds were purified on a Gilson 215 preparative LC system equipped with a Phenomenx Luna 5u C18 50 × 30 mm column by running a gradient of 20–60 % acetonitrile in 0.1 % trifluoroacetic acid in water at a flow rate of 50 mL/min over approximately 5 minutes. All compounds described within this manuscript are >95% pure by HPLC (254 nm, 214 nm and ELSD) as well as 1H NMR. All yields refer to analytically pure and fully characterized materials (1H NMR, 13C NMR, analytical LCMS and HRMS).

1-benzyl-4-((3-fluorophenyl)amino)piperidine-4-carboxamide (18a)

To a solution of 1-benzylpiperidin-4-one (13.25 g, 70 mmol) in glacial acetic acid (70 mL) and water (12 mL) cooled to 0 degrees Celsius was added 3-fluoroaniline (8.55 g, 77 mmol) and potassium cyanide (4.55 g, 70 mmol). The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and agitated for approximately 12 hours. The reaction was then cooled to 0 degrees Celsius and ammonium hydroxide (18 M) was added dropwise until the solution pH was 11 or greater. The mixture was then extracted into dichloromethane and dried under reduced pressure to yield the crude product as a tan oil (20.5 g). The crude product was then immediately cooled to 0 degrees Celsius and concentrated sulfuric acid (18 M, 120 mL) was added dropwise. The reaction was allowed to warm to room temperature and agitated for approximately 12 hours. The reaction was then cooled to 0 degrees Celsius and ammonium hydroxide (18 M) was added dropwise until the solution pH was 11 or greater. The mixture was then extracted into dichloromethane and dried under reduced pressure to afford a tan solid (15.78 g, 48.25 mmol, 68 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.51 - 7.37 (m, 7H), 6.67 - 6.47 (m, 4H), 4.27 (s, 1H), 3.64 (s, 2H), 2.95 - 2.87 (m, 2H), 2.53 - 2.44 (m, 2H), 2.29 - 2.21 (m, 2H), 2.07 (d, J = 13 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 178.0, 162.6, 145.7, 138.3, 130.5, 129.1 (2C), 128.4 (2C), 127.2, 111.8, 106.1, 103.1, 63.1, 58.5, 48.7 (2C), 34.8, 31.5; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C19H23N3OF [M+H]+ calculated 328.1825, found 328.1827; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.855; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 328.2.

1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one (20a)

1-Benzyl-4-((3-fluorophenyl)amino)piperidine-4-carboxamide 18a (15.78 g, 48.25 mmol), trimethyl orthoformate (80 mL), and glacial acetic acid (40 mL) were combined and subjected to microwave irradiation at 150 degrees Celsius for 15 minutes. The mixture was adjusted to pH 12 with ammonium hydroxide (18 M) and extracted into dichloromethane and dried under reduced pressure. This material was then added to a suspension of sodium borohydride (4.56 g, 120.6 mmol) in methanol (150 mL) and stirred for about 3 hours. The reaction was quenched with water, extracted into dichloromethane, and dried under reduced pressure. The material was then chromatographed on a 330 g flash column (Teledyne) as follows: (1) a gradient from 0–80 % ethyl acetated in hexanes over 10 minutes was run, and on the same column (2) a gradient from 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane was run. The purity of the isolated intermediate compound was established via LCMS, rt (min) 1.723; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 340.1. This intermediate 19a (1.94 g) was immediately dissolved in methanol (40 mL) and glacial acetic acid (10 mL), and treated with palladium on carbon (cat., 80 mg) under an atmosphere of hydrogen. After about 36 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite, concentrated under reduced pressure, diluted with water, made alkaline with saturated sodium bicarbonate and extracted 8 times into dichloromethane to afford a white solid (1.37 g, 5.49 mmol, 11 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.67 (s, 1H), 7.20 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 13 Hz, 1H), 6.52 - 6.46 (m, 1H), 4.57 (s, 2H), 3.20 - 3.09 (m, 3H), 2.91 - 2.82 (m, 2H), 2.46 - 2.36 (m, 2H), 1.48 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 176.0, 164.3, 145.0, 130.1, 109.3, 103.1, 100.2, 58.8, 58.6, 42.1 (2C), 28.9 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C13H17N3OF [M+H]+ calculated 250.1356, found 250.1351; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.394; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 250.1.

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21a)

1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20a (1370 mg, 5.49 mmol) and tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (961 mg, 6.03 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (25 mL) and methanol (10 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (3 g, 7.26 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (200 mg, 1.25 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on an 80 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (1.64 g, 4.18 mmol, 76 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.69 (s, 1H), 7.22 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.72 - 6.63 (m, 2H), 6.60 - 6.49 (m, 2H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 2.83 - 2.75 (m, 2H), 2.74 - 2.65 (m, 2H), 2.61 - 2.48 (m, 2H), 2.42 - 2.35 (m, 2H), 1.91 (s, 2H), 1.55 (d, J = 13 Hz, 2H), 1.39 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 175.8, 161.9, 155.6, 145.0, 130.4, 109.4, 103.2, 100.3, 77.5, 58.7, 58.1, 57.4, 49.3 (2C), 37.6, 28.3 (3C), 28.1 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C20H30N4O3F [M+H]+ calculated 393.2302, found 393.2301; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.966; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 393.2. tert-butyl (2-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)carbamate (1.64 g, 4.18 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (40 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 20 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 36 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (1.34 g, 3.66 mmol, 88 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.47 (s, 2H), 7.18 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.07 - 7.02 (m, 1H), 6.79 - 6.72 (m, 1H), 6.57 - 6.50 (m, 1H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.72 - 3.56 (m, 4H), 3.45 - 3.38 (m, 4H), 3.10 - 3.00 (m, 2H), 1.90 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4, 162.3, 144.4, 130.3, 109.8, 103.8, 100.2, 69.0, 56.5, 53.3, 49.1 (2C), 33.8, 25.6 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C15H22N4OF [M+H]+ calculated 293.1778, found 293.1776; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.405; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 293.1.

N-(2-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide (22a)

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 21a (1.23 g, 3.37 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (641 mg, 3.37 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (2.05 mL, 11.7 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (20 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was chromatographed on an 80 g flash column eluting in 0–5 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (1.25 g, 2.80 mmol, 83 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 8.69 (s, 1H), 8.60 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (s, 1H), 8.04 - 7.92 (m, 4H), 7.64 - 7.56 (m, 2H), 7.11 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.68 - 6.63 (m, 1H), 6.58 - 6.52 (m, 1H), 6.49 - 6.43 (m, 1H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 3.48 (q, J = 6 Hz, 2H), 2.91 - 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.80 - 2.72 (m, 2H), 2.64 - 2.53 (m, 4H), 1.58 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 175.9, 166.2, 164.3, 161.9, 145.0, 134.1, 132.2, 130.3, 128.8, 127.8, 127.6, 127.5, 127.3, 126.7, 124.1, 109.3, 103.3, 100.3, 58.7, 58.1, 56.9, 49.4 (2C), 37.3, 28.2 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2F [M+H]+ calculated 447.2196, found 447.2195; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.287; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 447.2. Analogs 22b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21a and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

N-(2-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide hydrochloride (22a-HCl)

N-(2-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide 22a (1.25 mg, 2.80 mmol) was stirred in methanol (30 mL) at room temperature and treated with hydrochloric acid (4M in dioxane, 4 mL). After about 25 minutes the compound was dried under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (1.31 g, 2.72 mmol, 97 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.99 (s, 1H), 9.14 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 9.11 (s, 1H), 8.60 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.97 (m, 4H), 7.65 - 7.57 (m, 2H), 7.21 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.05 - 7.01 (m, 1H), 6.83 - 6.77 (m, 1H), 6.58 - 6.52 (m, 1H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 3.85 - 3.75 (m, 2H), 3.74 - 3.64 (m, 4H), 3.41-3.36 (m, 2H), 3.11 - 2.99 (m, 2H), 1.92 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4, 166.6, 164.6, 162.2, 144.6, 134.3, 132.1, 131.2, 130.5, 128.9, 127.9, 127.8, 127.6, 126.8, 124.2, 109.9, 104.0, 100.3, 59.0, 56.6, 55.7, 48.7 (2C), 34.4, 25.7 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2F [M+H]+ calculated 447.2196, found 447.2186; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.264; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 447.2.

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21b)

1-(3-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20b (127 mg, 0.47 mmol) and tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (83.8 mg, 0.51 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) and methanol (0.05 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (600 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (41.9 mg, 0.25 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on a 12 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (72 mg, 0.18 mmol, 37 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.21 (t, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 6.95 - 6.90 (m, 2H), 6.86 - 6.78 (m, 1H), 4.69 (s, 2H), 3.23 - 3.02 (m, 4H), 2.81 - 2.67 (m, 4H), 1.97 (s, 2H), 1.78 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 178.2, 158.5, 145.8, 136.2, 141.3, 119.5, 115.4, 114.2, 80.3, 60.4, 60.1, 58.4, 50.7 (2C), 38.1, 29.2 (2C). 28.7 (3C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C20H30N4O3Cl [M+H]+ calculated 409.2006, found 409.1996; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.984; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 409.2. tert-butyl (2-(1-(3-chlorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)carbamate (72 mg, 0.17 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 1.0 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (60 mg, 0.16 mmol, 93 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.25 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 7.20 - 7.15 (m, 1H), 6.88 - 6.81 (m, 2H), 4.74 (s, 2H), 3.96 - 3.86 (m, 2H), 3.73 - 3.65 (m, 2H), 3.51 (s, 4H), 3.20 - 3.10 (m, 2H), 2.05 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 176.9, 145.2, 135.6, 131.5, 119.9, 115.1, 114.4, 60.5, 58.4, 54.9, 51.2 (2C), 35.4, 27.8 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C15H22N4OCl [M+H]+ calculated 309.1482, found 308.1480; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.413; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 309.1.

N-(2-(1-(3-chlorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (23a)

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 21b (60 mg, 0.15 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (30.0 mg, 0.15 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.115 mL, 0.66 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (43.4 mg, 0.075 mmol, 50 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.32 (s, 1H), 9.13 (s, 1H), 9.01 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.94 (m, 4H), 7.66 - 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.22 (t, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.98 - 6.94 (m, 1H), 6.86 - 6.80 (m, 2H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 3.79 - 3.68 (m, 6H), 3.44 - 3.39 (m, 2H), 2.88 - 2.75 (m, 2H), 1.97 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.3, 167.0, 158.6, 144.2, 134.3, 134.2, 132.1, 131.2, 130.4, 128.9 (2C), 128.0, 127.8, 127.7 (2C), 126.9, 124.1, 117.7, 113.2, 112.5, 59.0, 56.6, 55.3, 48.9 (2C), 34.6, 26.0 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2Cl [M+H]+ calculated 463.1901, found 463.1894; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.266; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 463.1. Analogs 23b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21b and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

(S)-8-(2-aminopropyl)-1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21c)

1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20c (104.8 mg, 0.39 mmol) and (S)-tert-butyl (1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate (74.6 mg, 0.43 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) and methanol (0.05 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (600 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of (S)-tert-butyl (1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate (37.3 mg, 0.22 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on a 12 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (60 mg, 0.14 mmol, 36 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.15 (q, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 7.00 - 6.92 (m, 1H), 6.76 - 6.70 (m, 1H), 4.67 (s, 2H), 3.98 - 3.80 (m, 1H), 3.18 - 3.09 (m, 1H), 2.83-2.52 (m, 5H), 1.96 (s, 2H), 1.83 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 1.17 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 178.0, 158.1, 152.9, 150.6, 141.5, 118.4, 113.2, 106.3, 80.5, 63.8, 60.8, 59.9, 51.4 (2C), 44.6, 29.1 (2C), 28.7 (3C), 19.6; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C21H31N4O3F2 [M+H]+ calculated 425.2364, found 425.2367; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.028; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 425.2. (S)-tert-butyl (1-(1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)propan-2-yl)carbamate (60 mg, 0.14 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 1.0 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (51 mg, 0.13 mmol, 93 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.61 (br s, 2H), 7.18 (q, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.12 - 7.05 (m, 1H), 7.01 - 6.95 (m, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 3.96 - 3.57 (m, 5H), 3.56-3.46 (m, 2H), 3.06 - 2.92 (m, 2H), 1.91 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H), 1.32 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4, 151.2, 148.8, 139.9, 117.2, 110.2, 103.2, 59.4, 59.2, 56.6, 50.6, 48.6, 42.5, 25.8, 25.6, 17.1; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C16H23N4OF2 [M+H]+ calculated 325.1840, found 325.1839; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.344; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 325.1.

(S)-N-(1-(1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)propan-2-yl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (24a)

(S)-8-(2-aminopropyl)-1-(3,4-difluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 21c (40 mg, 0.10 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (19.1 mg, 0.10 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.073 mL, 0.42 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (29.2 mg, 0.05 mmol, 49 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.69 (s, 1H), 9.08 (s, 1H), 8.77 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.05 - 7.95 (m, 4H), 7.66 - 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.25 (q, J = 10 Hz, 1H), 7.02 - 6.95 (m, 1H), 6.74 - 6.69 (m, 1H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 3.85 - 3.68 (m, 4H), 3.60 - 3.53 (m, 1H), 3.43 - 3.31 (m, 2H), 2.78 - 2.57 (m, 2H), 2.01 - 1.89 (m, 2H), 1.31 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.3, 166.5, 158.2, 148.6, 140.1, 134.3, 132.1, 131.4, 128.8, 127.8, 127.7 (2C), 127.6, 126.8, 124.4, 117.6, 117.5, 110.9, 104.1, 103.9, 60.7, 59.2, 56.7, 49.8, 48.6, 41.2, 26.1, 26.0, 19.0; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C27H29N4O2F2 [M+H]+ calculated 479.2259, found 479.2262; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.286; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 479.2. Analogs 24b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21c and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21d)

1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20d (54.8 mg, 0.22 mmol) and tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (38.2 mg, 0.24 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) and methanol (0.05 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (600 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (19.1 mg, 0.12 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on a 12 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (41 mg, 0.10 mmol, 47 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.10 - 7.02 (m, 4H), 4.67 (s, 2H), 3.28 - 3.24 (m, 2H), 3.20 - 3.12 (m, 2H) 2.86 - 2.80 (m, 2H), 2.44 - 2.37 (m, 2H), 1.95 (s, 2H), 1.88 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.44 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 178.4, 160.7, 158.4, 140.8, 122.3, 122.2, 116.7, 116.5, 80.4, 61.2, 60.1, 58.1, 50.6 (2C), 37.5, 29.5 (2C), 28.7 (3C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C20H30N4O3F [M+H]+ calculated 393.2302, found 393.2300; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.850; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 393.2. tert-butyl (2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)carbamate (41 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 0.5 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (34 mg, 0.093 mmol, 93 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.16 - 7.08 (m, 2H), 7.08 - 7.00 (m, 2H), 4.72 (s, 2H), 3.92 - 3.81 (m, 2H), 3.72 - 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.50 (s, 4H), 2.93-2.81 (m, 2H), 2.05 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 177.3, 160.3, 140.1, 120.5, 120.4, 116.9, 116.7, 61.1, 58.6, 54.9, 51.3 (2C), 35.4, 28.5 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C15H22N4OF [M+H]+ calculated 293.1778, found 293.1769; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.260; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 293.2.

N-(2-(1-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (25a)

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (34 mg, 0.09 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (17.8 mg, 0.09 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.067 mL, 0.385 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (25.8 mg, 0.04 mmol, 51 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.92 (s, 1H), 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.97 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 8.48 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.94 (m, 4H), 7.66 - 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.09 (t, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 7.03 - 6.97 (m, 2H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 3.76 - 3.63 (m, 6H), 3.38 - 3.34 (m, 2H), 2.63 - 2.51 (m, 2H), 1.97 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.7, 166.9, 157.6, 155.3, 139.3, 134.3, 132.1, 131.2, 128.9 (2C), 128.0, 127.8, 127.7 (2C), 126.9, 124.1, 118.2, 118.1, 115.7, 115.5, 59.2, 56.7, 55.3, 50.0 (2C), 34.6, 26.5 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2F [M+H]+ calculated 447.2196, found 447.2196; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.140; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 447.2. Analogs 25b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21d and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21e)

1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20e (152 mg, 0.57 mmol) and tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (100 mg, 0.63 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) and methanol (0.05 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (600 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (76 mg, 0.32 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on a 12 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (108 mg, 0.26 mmol, 46 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.23 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 6.96 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.69 (s, 2H), 3.39 - 3.32 (m, 2H), 3.26 - 3.17 (m, 2H), 2.90 - 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.78 - 2.67 (m, 2H), 1.97 (s, 2H), 1.84 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H);13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 178.0, 158.5, 143.1, 130.1 (2C), 125.4, 118.1 (2C), 80.5, 60.6, 59.6, 58.2, 50.6 (2C), 37.6, 28.8 (2C), 28.7 (3C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C20H30N4O3Cl [M+H]+ calculated 409.2006, found 409.2006; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.002; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 409.2. tert-butyl (2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)carbamate (108 mg, 0.26 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 1.5 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (94 mg, 0.25 mmol, 95 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.25 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.73 (s, 2H), 3.95 - 3.85 (m, 2H), 3.72 - 3.64 (m, 2H), 3.51 (s, 4H), 3.19 - 3.08 (m, 2H), 2.03 (d, J = 15 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 177.1, 142.5, 130.3 (2C), 125.3, 117.5 (2C), 60.6, 58.4, 55.0, 51.3 (2C), 35.5, 27.8 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C15H22N4OCl [M+H]+ calculated 309.1482, found 309.1479; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.420; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 309.1.

N-(2-(1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (26a)

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 21e (94 mg, 0.24 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (47.1 mg, 0.24 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.182 mL, 1.05 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (62.9 mg, 0.11 mmol, 45 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.24 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 9.01 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.94 (m, 4H), 7.65 - 7.57 (m,2 H), 7.23 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 3.78 - 3.65 (m, 6H), 3.40 - 3.33 (m, 2H), 2.85 - 2.72 (m, 2H), 1.96 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.5, 166.9, 158.9, 141.7, 134.3, 132.1, 131.2, 128.9 (2C), 128.7 (2C), 128.0 (2C), 127.8, 127.7 (2C), 126.8, 124.1, 122.1, 115.7, 59.0, 56.5, 55.2, 48.9 (2C), 34.6, 26.0 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2Cl [M+H]+ calculated 463.1901, found 463.1897; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.249; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 463.2. Analogs 26b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21e and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (21f)

1-(4-bromophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20f (177 mg, 0.57 mmol) and tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (100 mg, 0.63 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (1.5 mL) and methanol (0.05 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (600 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added to the reaction and after 14 hours an additional amount of tert-butyl (2-oxoethyl)carbamate (76 mg, 0.32 mmol) was added to drive the reaction to completion. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on a 12 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (163 mg, 0.36 mmol, 63 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.35 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.68 (s, 2H), 3.29 - 3.21 (m, 2H), 3.20 - 3.10 (m, 2H), 2.86 - 2.68 (m, 4H), 1.97 (s, 2H), 1.80 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 176.2, 155.6, 143.4, 129.0 (2C), 117.6, 114.3 (2C), 77.5, 58.6, 58.2, 57.4, 49.3 (2C), 37.7, 28.3 (2C), 28.3 (3C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C20H30N4O3Br [M+H]+ calculated 453.1501, found 453.1504; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.048; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 455.1. tert-butyl (2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)carbamate (163 mg, 0.35 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 1.5 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a white solid (140 mg, 0.33 mmol, 94 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.48 (br s, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 7.09 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 3.71 - 3.58 (m, 4H), 3.47 - 3.38 (m, 4H), 3.09 - 2.97 (m, 2H), 1.89 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.5, 141.8, 131.5 (2C), 115.9 (2C), 109.1, 58.9, 56.4, 53.3, 49.2 (2C), 33.7, 25.5 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) C15H22N4OBr [M+H]+ calculated 353.0977, found 353.0977; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.467; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 353.1.

N-(2-(1-(4-bromophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)ethyl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (27a)

8-(2-aminoethyl)-1-(4-bromophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 21f (66 mg, 0.15 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (29.5 mg, 0.15 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.126 mL, 0.73 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (1 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (66.1 mg, 0.11 mmol, 71 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 10.23 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 9.00 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.93 (m, 4H), 7.65 - 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.34 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.78 - 3.66 (m, 6H), 3.46 - 3.40 (m, 2H), 2.86 - 2.74 (m, 2H), 1.95 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.5, 166.9, 158.9, 142.1, 134.3, 132.1, 131.6 (2C), 131.2, 128.9 (2C), 128.0 (2C), 127.8, 127.7 (2C), 126.8, 124.1, 116.1, 109.6, 58.9, 56.5, 55.2, 48.9 (2C), 34.6, 25.9 (2C); HRMS (TOF, ESI) HRMS (TOF, ESI) C26H28N4O2Br [M+H]+ calculated 507.1396, found 507.1393; LC-MS: rt (min) = 2.279; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 507.1. Analogs 27b–d were made following the same protocol starting from 21f and were purified via reversed-phase chromatography to greater than 95% purity (as trifluoroacetate salts) as analyzed by ELSD and UV at both 214 and 254 nM.

(S)-tert-butyl (1-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)propan-2-yl)carbamate (29)

1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one 20a (366 mg, 1.46 mmol) and (S)-tert-butyl (1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamate (356 mg, 2.00 mmol) were combined and dissolved in dichloromethane (10 mL) and methanol (1 mL) and stirred for about 30 minutes at room temperature. After about 30 minutes macroporous triacetoxyborohydride (2 g, 4.84 mmol) was added to the reaction. After about 24 hours the reaction mixture was filtered through celite and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude compound was chromatographed on an 80 g flash column eluting in a gradient of 0–10 % methanol in dichloromethane to afford a white solid (191 mg, 0.47 mmol, 34 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 7.23 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 - 6.68 (m, 2H), 6.55 - 6.49 (m, 1H), 4.69 (s, 2H), 3.96 - 3.84 (m, 1H), 3.25 - 3.07 (m, 2H), 2.90 - 2.63 (m, 4H), 1.96 (s, 2H), 1.79 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H), 1.18 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, MeOD) δ (ppm): 178.2, 164.0, 158.3, 146.2, 131.6, 111.3, 105.7, 102.4, 80.5, 64.2, 60.5 (2C), 59.8, 51.5, 50.5, 28.9 (2C), 28.7 (3C), 19.6; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C21H32N4O3F [M+H]+ calculated 407.2458, found 407.2449; LC-MS: rt (min) = 1.932; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 407.2.

(S)-8-(2-aminopropyl)-1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride (30)

(S)-tert-butyl (1-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)propan-2-yl)carbamate 29 (166 mg, 0.40 mmol) was dissolved in dichloromethane (15 mL) and a minimal amount of methanol added dropwise. Hydrochloric acid was added (4M in dioxane, 2.0 mL) and the reaction was stirred for approximately 16 hours at room temperature. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a light tan solid (150 mg, 0.39 mmol, 98 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.63 (s, 2H), 7.22 - 7.12 (m, 1H), 7.08 - 7.01 (m, 1H), 6.79 - 6.72 (m, 1H), 6.56 - 6.49 (m, 1H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.95 - 3.58 (m, 4H), 3.54 - 3.41 (m, 3H), 3.15 - 3.00 (m, 2H), 1.89 (d, J = 14 Hz, 2H), 1.32 (d, J = 5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.3, 162.1, 144.4, 130.2, 109.8, 103.9, 100.5, 59.4, 58.9, 56.5, 50.5, 48.5, 42.4, 25.7, 25.5, 17.1; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C16H24N4OF [M+H]+ calculated 307.1934, found 307.1934; LC-MS: rt (min) = 0.255; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 307.1.

(S)-N-(1-(1-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-oxo-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl)propan-2-yl)-2-naphthamide 2,2,2-trifluoroacetate (31)

(S)-8-(2-aminopropyl)-1-(3-fluorophenyl)-1,3,8-triazaspiro[4.5]decan-4-one dihydrochloride 30 (140 mg, 0.37 mmol), 2-naphthoyl chloride (76 mg, 0.40 mmol) and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (0.225 mL, 1.29 mmol) were all dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (5 mL) at 0 degrees Celsius. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for about 12 hours. The reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted into dichloromethane 5 times. The dichloromethane layer was then washed 3 times with a solution of lithium chloride (3M) and dried under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was subjected to reversed-phase chromatography to afford a white solid (19.3 mg, 0.03 mmol, 9 %). 1H NMR (400.1 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 9.74 (s, 1H), 9.10 (s, 1H), 8.78 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.06 - 7.95 (m, 4H), 7.66 - 7.58 (m, 2H), 7.20 (q, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 6.76 - 6.69 (m, 2H), 6.60 - 6.53 (m, 1H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.88 - 3.69 (m, 3H), 3.61 - 3.54 (m, 1H), 3.43 - 3.33 (m, 3H), 2.93 - 2.71 (m, 2H), 2.01 - 1.82 (m, 2H), 1.31 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 174.4, 166.7, 162.1, 144.7, 134.3, 132.1, 131.4, 130.6, 130.5, 128.9, 127.9 (2C), 127.8 (2C), 127.7, 126.9, 124.4, 109.8, 104.3, 100.9, 60.8, 59.0, 56.6, 49.8, 48.7, 41.3, 26.0, 25.8, 19.0; HRMS (TOF, ESI) C27H30N4O2F [M+H]+ calculated 461.2353, found 461.2354; LC-MS: rt (min) = 0.445; LRMS (ESI) m/z = 461.2.

PHARMACOLOGY METHODS

Cell Culture

Calu-1, and MDA-231 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Calu-1 and MDA-231 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin. HEK293 cells stably expressing GFP tagged human PLD2A were generated in the lab. To sustain selection pressure low passage-number HEK293-gfpPLD2 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 2 μg/mL puromycin and 600 μg/mL G418. All HEK293-gfpPLD2 experiments were done on tissue culture plates that had been coated with low levels of poly-lysine. All cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Cellular Phospholipase D activity assays

PLD1 and PLD2 cellular IC50 values were determined as described previously.26

Assessment of Cell Proliferation via WST-1 Assay

Cells are plated into 96-well tissue culture plates at 15000 cells/well in tissue culture treated 96-well black wall/clear bottom assay plates (Corning Inc. Costar plates) in complete growth medium and allowed to grow overnight. After 24 hours of growth media was removed and cells are treated with PLD inhibitor or DMSO vehicle control in 100 μL of DMEM 1% AA either +/− 10% FBS. Media and inhibitor are replenished every 24 hours and after 48 hours cells were treated with 10 μL/well of a modified MTT reagent, WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). Plates were then incubated for 1 hr at 37 °C. After incubation UV absorbance was measured at 450 nm with, BioTek Synergy HT plate reader (BioTek Inc., Winooski, VT). Background signal was subtracted from wells with no cells present. Data is expressed as absorbance at 450 nm. For time course experiments cells were seeded at 7500 cells/well into media containing PLD inhibitor or DMSO vehicle control. Media was removed and replaced every 24 hours and at set time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 hours) cells were treated with WST-1 reagent as described above.

Assessment of Caspase 3/7 Activity

Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using a homogeneous bioluminescent method according to manufacturer’s directions (Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay, Promega, Madison, WI). In this assay, caspase-3/7 activity is measured by the ability to cleave the proluminescent Caspase 3/7 specific DEVD-aminoluciferin substrate to liberate the free aminoluciferin which is then consumed by luciferase generating a luminescent signal. The luminescent signal is directly proportional to the amount of Caspase 3/7 activity. Cells were plated at 15000 cells/well in tissue culture treated 96-well black wall/clear bottom assay plates (Corning Inc. Costar plates) in 50 μL growth medium at 37 °C. After 24 hours media was removed and replaced with DMEM, 1%AA, +/− 10% FBS with either PLD inhibitor or DMSO vehicle control. Media was replenished every 24 hours to account for metabolism of the compounds. After 48 hours growth in the presence of PLD inhibitor 50 μL Caspase-Glo 3/7 reagent was added to each well, plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and luminescent signal was then detected with BioTek Synergy HT plate reader (BioTek Inc.; Winooski, VT). Caspase 3/7 activity was normalized to vehicle control and expressed as fold stimulation of Caspase activity.

Pharmacokinetic Studies

In vitro

The metabolism of PLD inhibitors, 14 and 22a, was investigated in rat hepatic microsomes (BD Biosciences, Billerica, MA) using substrate depletion methodology (% test article remaining). A potassium phosphate-buffered reaction mixture (0.1 M, pH 7.4) of test article (1 μM) and microsomes (0.5 mg/mL) was pre-incubated (5 min) at 37°C prior to the addition of NADPH (1 mM). The incubations, performed in 96-well plates, were continued at 37°C under ambient oxygenation and aliquots (80 μL) were removed at selected time intervals (0, 3, 7, 15, 25 and 45 min). Protein was precipitated by the addition of chilled acetonitrile (160 μL), containing glyburide as an internal standard (50 ng/mL), and centrifuged at 3000 rpm (4°C) for 10 min. Resulting supernatants were transferred to new 96-well plates in preparation for LC/MS/MS analysis. The in vitro half-life (t1/2, min, Eq. 1), intrinsic clearance (CLint, mL/min/kg, Eq. 2) and subsequent predicted hepatic clearance (CLhep, mL/min/kg, Eq. 3) was determined employing the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In vivo

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=2) weighing around 300g were purchased from Harlon laboratories (Indianapolis, IN) and implanted with catheters in the carotid artery and jugular vein. The cannulated animals were acclimated to their surroundings for approximately one week before dosing and provided food and water ad libitum. Compounds 14 and 22a were administered intravenously (IV) to rats via the jugular vein catheter in 20% DMSO/80% saline at a dose of 1 mg/kg and a dose volume of 1 mL/kg. Blood collections via the carotid artery were performed at pre-dose, and at 2 min, 7 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 7 and 24 hrs post dose. Samples were collected into chilled, EDTA-fortified tubes, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm (4°C), and resulting plasma aliquoted into 96-well plates for LC/MS/MS analysis. All pharmacokinetic analysis was performed employing noncompartmental analysis. For oral exposure studies, measuring both systemic plasma and CNS tissue exposure, compounds 14 and 22a were administered (oral gavage) to fasted rats (n=2) as suspensions in 10% tween 80/0.5% methylcellulose at a dose of 10 mg/kg and in a dosing volume of 10 mL/kg; blood and whole brain samples were collected at 1.5h post dose. Blood was collected into chilled, EDTA-fortified tubes, centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm (4°C) and stored at −80 °C until LC/MS/MS analysis. The brain samples were rinsed in PBS, snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Prior to LC/MS/MS analysis, brain samples were thawed to room temperature and subjected to mechanical homogenation employing a Mini-Beadbeater™ and 1.0 mm Zirconia/Silica Beads (BioSpec Products). All animal studies were approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animal care and use program is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International.

Plasma Protein Binding

Protein binding of the PLD inhibitors, 14 and 22a, was determined in rat plasma via equilibrium dialysis employing Single-Use RED Plates with inserts (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rochester, NY). Briefly plasma (220 μL) was added to the 96 well plate containing test article (5 μL) and mixed thoroughly. Subsequently, 200 μL of the plasma-test article mixture was transferred to the cis chamber (red) of the RED plate, with an accompanying 350 μL of phosphate buffer (25 mM, pH 7.4) in the trans chamber. The RED plate was sealed and incubated 4 h at 37°C with shaking. At completion, 50 μL aliquots from each chamber were diluted 1:1 (50 μL) with either plasma (cis) or buffer (trans) and transferred to a new 96 well plate, at which time ice-cold acetonitrile (2 volumes) was added to extract the matrices. The plate was centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min) and supernatants transferred to a new 96 well plate. The sealed plate was stored at −20°C until LC/MS/MS analysis.

Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis

In vivo experiments

PLD inhibitors, 14 and 22a, were analyzed via electrospray ionization (ESI) on an AB Sciex API-4000 (Foster City, CA) triple-quadrupole instrument that was coupled with Shimadzu LC-10AD pumps (Columbia, MD) and a Leap Technologies CTC PAL auto-sampler (Carrboro, NC). Analytes were separated by gradient elution using a Fortis C18 2.1 × 50 mm, 3.5 μm column (Fortis Technologies Ltd, Cheshire, UK) thermostated at 40°C. HPLC mobile phase A was 0.1% NH4OH (pH unadjusted), mobile phase B was acetonitrile. The gradient started at 30% B after a 0.2 min hold and was linearly increased to 90% B over 0.8 min; held at 90% B for 0.5 min and returned to 30% B in 0.1 min followed by a re-equilibration (0.9 min). The total run time was 2.5 min and the HPLC flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. The source temperature was set at 500°C and mass spectral analyses were performed using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), with transitions for 14 (m/z 497.5→202.3) and 22a (m/z 447.4→198.1) utilizing a Turbo-Ionspray® source in positive ionization mode (5.0 kV spray voltage). All data were analyzed using AB Sciex Analyst 1.4.2 software.

In vitro experiments

The PLD inhibitors were analyzed similarly to that described above (In vivo) with the following exceptions: LC/MS/MS analysis was performed employing a TSQ Quantum ULTRA that was coupled to a ThermoSurveyor LC system (Thermoelectron Corp., San Jose, CA) and a Leap Technologies CTC PAL auto-sampler (Carrboro, NC). Chromatographic separation of analytes was achieved with an Acquity BEH C18 2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm column (Waters, Taunton, MA).

Acknowledgments

R.R.L. was supported by an NIH integrative training in therapeutic discovery training Grant (T90DA022873), John S. McDonnell Foundation (HAB & CWL). The authors also wish to thank Katrina Brewer and Matthew Mulder for in vitro drug metabolism stability and protein binding data.

Abbreviations

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PLD

Phospholipase D

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- gfp

green fluorescence protein

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

- NAM

negative allosteric modulator

- FBS

fetal bovine

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown HA, Henage LG, Preininger AM, Xiang Y, Exton JH. Biochemical analysis of phospholipase D. Methods Enzymol. 2007;434:49–87. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)34004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster DA. Phosphatidic acid signaling to mTOR: Signals for the survival of human cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:949–955. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noh DY. Overexpression of phospholipase D1 in human breast cancer tissues. Cancer Lett. 2000;161:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Y, Ehara H, Akao Y, Shamoto M, Nakagawa Y, Banno Y, Deguchi T, Ohishi N, Yagi K, Nozawa Y. Increased activity and intranuclear expression of phospholipase D2 in human renal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:140–143. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada Y. Association of a polymorphism of the phospholipase D2 gene with the prevalence of colorectal cancer. J Mol Med. 2003;81:126–131. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0411-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MH, Ahn BH, Hong YK, Min DS. Overexpression of phospholipase D enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression and glioma cell invasion via protein kinase C and protein kinase A/NF-kappa B/Sp1-mediated signaling pathways. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:356–365. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchanan FG, McReynolds M, Couvillon A, Kam Y, Holla VR, DuBois RN, Exton JH. Requirement of phospholipase D1 activity in H-Ras(V12)-induced transformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:1638–1642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406698102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Rodrik V, Toschi A, Shi M, Hui L, Shen Y, Foster DA. Phospholipase D couples survival and migration signals in stress response of human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006:281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi M, Zheng Y, Garcia A, Xu L, Foster DA. Phospholipase D provides a survival signal in human cancer cells with activated H-Ras or K-Ras. Cancer Lett. 2007;258:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snider AJ, Zhang ZH, Xie YH, Meier KE. Epidermal growth factor increases lysophosphatidic acid production in human ovarian cancer cells: roles for phospholipase D-2 and receptor transactivation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2010;298:C163–C170. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00001.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williger BT, Ho WT, Exton JH. Phospholipase D mediates matrix metalloproteinase-9 secretion in phorbol ester-stimulated human fibrosarcoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:735–738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui L, Zheng Y, Yan Y, Bargonetti J, Foster DA. Mutant p53 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells is stabilized by elevated phospholipase D activity and contributes to survival signals generated by phospholipase D. Oncogene. 2006;25:7305–7310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hui L, Abbas T, Pielak RM, Joseph T, Bargonetti J, Foster DA. Phospholipase D elevates the level of MDM2 and suppresses DNA damage-induced increases in p53. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5677–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5677-5686.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Rodrik V, Foster DA. Alternative phospholipase D/mTOR survival signal in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:672–679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui L, Rodrik V, Pielak RM, Knirr S, Zheng Y, Foster DA. mTOR-dependent suppression of protein phosphatase 2A is critical for phospholipase D survival signals in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35829–35835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504192200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao C. Phospholipase D2-generated phosphatidic acid couples EGFR stimulation to Ras activation by Sos. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:706–712. doi: 10.1038/ncb1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tou JS, Urbizo C. Diethylstilbestrol inhibits phospholipase D activity and degranulation by stimulated human neutrophils. Steroids. 2008;73:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tou JS, Urbizo C. Resveratrol inhibits the formation of phosphatidic acid and diglyceride in chemotactic peptide- or phorbol ester-stimulated human neutrophils. Cellular Signalling. 2001;13:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia A, Zheng Y, Zhao C, Toschi A, Fan J, Shraibman N, Brown HA, Bar-Sagi D, Foster DA, Arbiser JL. Honokiol suppresses survival signals mediated by Ras-dependent phospholipase D activity in human cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4267–4274. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]