Abstract

Background

A new generation of medical students is seeking residency programs offering global health education (GHE), and there is growing awareness of the benefits this training provides. However, basic factors that have an impact on its implementation and its effect on the residency match are insufficiently understood. The purpose of this study was to explore the extent of online information on GHE available to potential US pediatric residency program applicants.

Methods

Pediatric residency programs' websites were systematically examined in 2007, 2008, and 2009 to extract available information on GHE.

Results

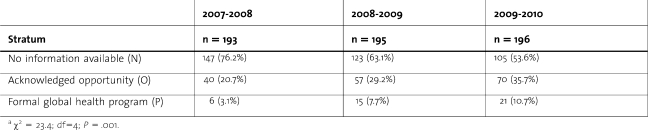

In 2007, 147 websites (76.2%) had no information available on GHE; 40 (20.7%) mentioned international opportunities; and 6 (3.1%) provided evidence of a global health track or program. In 2008, 123 websites (63.1%) had no information available on GHE; 57 (29.2%) mentioned international opportunities; and 15 (7.7%) had a formal program. In 2009, 105 websites (53.6%) had no information available on GHE; 70 (35.7%) mentioned international opportunities; and 21 (10.7%) had a formal program. Between 2007 and 2009, the percentage of pediatric residency programs with information on GHE available nearly doubled from 23.8% to 46.4%. Within the same period, the number of formal GHE programs offered more than tripled.

Conclusions

By the 2009–2010 academic year, the websites for nearly half of the residency programs mentioned international experiences, yet only a small number of these residencies appeared to have developed a formal GHE program. Further, the websites for many residency programs did not include information on the international opportunities they offered, with programs running the risk of failing to attract and ultimately match global health–minded applicants.

Background

Global health has captured the attention of today's medical students. Studies on global health education have highlighted the benefits of participation in global electives on participants' clinical and communication skills.1–3 Not surprisingly, innovative US medical schools and residency programs are integrating global health into their classroom instruction, clinical rotations, and research opportunities.4,5 In 2007, a survey of pediatric training programs found that a considerable percentage reported that most of their residents expressed interest in global health training.6 Thus, availability of international educational opportunities and up-to-date online information on this are significant factors applicants may consider when selecting a place to train.7–10

Although the exchange of information between residency programs and applicants once relied on printed materials, it now primarily depends on a virtual interchange.8 The popularization of the World Wide Web has reshaped the US residency application process. Today, applicants weigh and consider information on programs' websites at every step of the process, from deciding where to apply, to the final generation of their program rank-order list.8 However, little is known about the information on global health training available online to applicants, and even less is known on how such information may affect their decisions during the program selection and matching process. The purpose of this study was to explore the online information on global health education available to potential applicants on US pediatric residency programs' websites during a 3-year period.

Methods

The Graduate Medical Education Directory, published by the American Medical Association, and the American Medical Association–Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access (AMA-FREIDA) were used as references to obtain a list of pediatric residency programs recognized by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. All residency programs listed in the 2 directories were included; pediatric residencies not included in AMA-FREIDA were excluded from the study. Programs were excluded from the study if they did not have a website. There was no residency program that did not have at least a rudimentary website by 2008; in 2009, one additional residency was listed by AMA-FREIDA.

Data Collection

All pediatric programs' websites were systematically examined during the 2007–2008, 2008–2009, and 2009–2010 academic years (AYs) to extract online information on residency size and global health training opportunities available to potential applicants. Each website was accessed using the web address listed in AMA-FREIDA in the fall of the AY to correspond with the manner and the time period in which potential applicants typically explore these sites. If this web address was not a direct link to the pediatric residency home page, each linked website was navigated until the program's home page was found. The websites were queried, and each website's curriculum and residency program descriptions were reviewed for any documented opportunity abroad.

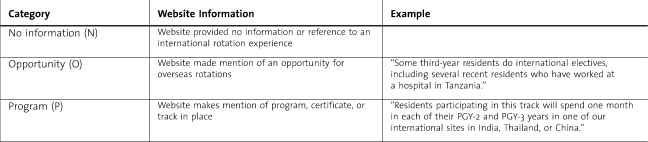

After the publicly accessible program descriptions were systematically reviewed, the data were combined into one database. Two coders (J.C. and H.C.) independently reviewed the complete database and coded the information independently using a predetermined 3-strata code system (table 1), and the interrater reliability was calculated. The 2 coders then reviewed and compared their coded transcripts and resolved coding discrepancies. The institutions' websites that met the (P) code criteria by AY 2009–2010 were further reviewed for the components of a formal global health program in order to understand the nature of the training provided. The Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board determined this study to be exempt from review.

Table 1.

Classification of Information Published Online

Data Analysis

The proportion of websites in each stratum by year was compared using Pearson χ2. A P value <.05 was accepted as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Interrater reliability between the coders was estimated using Cohen κ statistic.11

Results

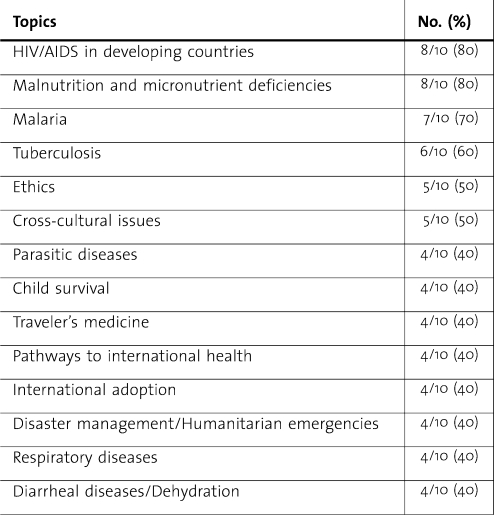

A total of 193, 195, and 196 websites were reviewed and classified for each of the 3 academic years, respectively (table 2). Prior to reconciliation of discrepant classifications, the interrater reliability was calculated (κ = 0.97). The proportion of websites offering no information, an acknowledged opportunity, or a formal program varied significantly by year (P < .001). The mean overall size of the 21 pediatric programs that provided evidence of a track or formal program (P) was 71.9 residents in AY 2009–2010 (range, 18–120). Training in these programs, as reported on their websites, included a lecture series on global health in 95.2% (20 of 21). The lecture series was detailed in 47.6% (10 of 21) of those websites (table 3). Thirty-three percent (7 of 21) of these programs advertised a global health journal club. Availability of resident involvement in global health activities for at least 2 months was reported by 57.1% (12 of 21) of these programs. Multiple and specific international sites were listed by 76% (16 of 21), and these opportunities were described in 47.6% (10 of 21) of the websites. Research opportunities in global health were publicized by 76.2% (16 of 21) of the programs, and 66.7% (14 of 21) described available mentorship. Last, only 33.3% (7 of 21) of the formal programs mentioned funding for global health training opportunities on their website.

Table 2.

Global Health Information Available at Pediatric Residency Training Websitesa

Table 3.

Prevalence of Global Health Topics in Programs with Curriculum Reported Online

Discussion

This study supports the premise that interest in global health education has greatly increased among pediatric residency programs. Even so, by AY 2009–2010 only 46.4% of pediatric residency programs had made known the availability of their international experiences to potential applicants on the program website. Further, only a subset of all programs (10.7%) appeared to have invested in the development of a formal global health training program. Thus, despite mounting interest among medical students, investment by pediatric residency programs in the development of formal educational opportunities for pediatric residents appears to be relatively low.

In a 1995 survey, 25% of pediatric residency programs offered some global health electives.12 More than a decade later, pediatric residency programs are beginning to integrate global health more widely into their curricula, with a 2007 survey finding that 52% of responding pediatric programs offered a global health elective.6 However, only 6 programs reported a formal global health program.6 In a similar cohort and time period, we found that through their websites 46 programs (23.8%) acknowledged a global health opportunity, and 6 (3.1%) provided evidence of a formal program.

Although Nelson et al6 identified half of responding residencies as having offered a global health elective, our study found that only a small proportion of programs (23.8%) made this information available online to potential applicants. There may be several reasons for these different findings. First, a lag may have existed in the updating of web-based information by residency programs. Second, a biased sample may have resulted if the programs with the global health electives more readily responded to the 2007 Nelson survey, with the response rate of only 53% suggesting the possibility of selection bias. Similar to findings by Nelson et al,6 in our study large residency program size (>60 total residents) and mentorship surfaced as common characteristics of the residencies with formal global health training programs. Most programs also offered a planned didactic component (ie, a lecture series and journal club), but funding for global health electives appeared to be less common.

In an environment of increasing interest in global health training, there seems to be a disparity between the interest level and the opportunities available, and between the opportunities available and their description online. During the 3 years of our survey period, there was a striking increase in global health training information posted on pediatric residency websites.

Our study has several limitations. Given the observational nature of our methods, we must be careful not to overstate the apparent association between information posted on residency websites and institutional investment, development of educational opportunities, and formal global health training programs. In addition, in the absence of direct interviews of residency program directors, we cannot exclude the possibility that the lack of online information merely represents a natural lag in website development and updating.

Conclusions

Our findings show that despite mounting interest in global health education among learners, in AY 2009–2010 fewer than half of pediatric residency programs had publicized global health training opportunities. However, the 3 years of our study period saw a striking increase in global health training information posted on pediatric residency websites. Our findings suggest the growing value of web information in informing residents about the availability of global health opportunities underscores their value as recruitment and selection tools.

Global health training is highly desired by today's learners, and may be a natural instrument to encourage altruism and better care for underserved populations at home and abroad. Future research is needed to support the claims of benefits of international rotations on US practice and access to care for underserved populations.

Footnotes

All authors are from Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Jonathan Castillo, MD, MPH, is a Clinical Fellow in the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; Heidi Castillo, MD, is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics; and Thomas G. DeWitt, MD, is Director of the Division of General and Community Pediatrics, The Carl Weihl Professor of Pediatrics, and Associate Chair for Education.

Funding: This research was funded by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (Health Resources and Services Administration grant T32 HP10027). The authors would like to thank Dr David J. Schonfeld, Dr Raymond C. Baker, and Kevin E. Stanford for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Bissonette R, Route C. The educational effect of clinical rotations in nonindustrialized countries. Fam Med. 1994;26(4):226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32(8):566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castillo J, Goldenhar LM, Baker RC, Kahn RS, DeWitt TG. Reflective practice and competencies in global health training: lesson for serving diverse patient populations. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):449–455. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00081.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heck JE, Wedemeyer D. International health education in US medical schools: trends in curriculum focus, student interest, and funding sources. Fam Med. 1995;27(10):636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):320–325. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson BD, Lee AC, Newby PK, Chamberlin MR, Huang CC. Global health training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):28–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazemore AW, Henein M, Goldenhar LM, Szaflarski M, Lindsell CJ, Diller P. The effect of offering international health training opportunities on family medicine residency recruiting. Fam Med. 2007;39(4):255–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Embi PJ, Desai S, Cooney TG. Use and utility of Web-based residency program information: a survey of residency applicants. J Med Internet Res. 2003;5(3):e22. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5.3.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey CC, Grabowski JG, Gebreyes K, Hsu E, VanRooyen MJ. Influence of international emergency medicine opportunities on residency program selection. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(7):679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):226–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70(4):213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torjesen K, Mandalakas A, Kahn R, Duncan B. International child health electives for pediatric residents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(12):1297–1302. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.12.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leow JJ, Kingham TP, Casey KM, Kushner AL. Global surgery: thoughts on an emerging surgical subspecialty for students and residents. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(3):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]