Abstract

Background

While there is growing interest among residents in participating in international health experiences, it is unclear whether this interest will translate into intentions to pursue a global health career. We aimed to describe overall interest in and career intentions toward global health among interns.

Methods

We administered an anonymous survey to incoming interns in all specializations during graduate medical education orientation at 3 teaching hospitals affiliated with 2 Midwestern US medical schools in June 2009. Survey domains included demographics, previous global health experiences, interest in and barriers to participating in global health experiences during residency, and plans to pursue a future global health career.

Results

Response rate was 87% (299 of 345 residents). The most commonly reported barriers to participating in global health experiences were scheduling (82%) and financial (80%) concerns. Two-thirds of interns (65%) reported they were likely to focus on global health in their future career. Of those envisioning a global health career, 77% of interns reported interest in participating in short, occasional trips in the future; and 23% of interns intended to pursue a part-time or full-time career abroad. Interns committed to a career abroad were more willing to use vacation time (73% vs. 40% of all others, respectively; P < .001) or to personally finance the trip (58% vs. 27% of all others, respectively; P = < .001), and were less concerned about personal safety than interns not committed (9% vs. 26% of all others, respectively; P = .01).

Conclusions

Although a large proportion of incoming interns report interest in global health careers, few are committed to a global health career. Medical educators could acknowledge career plans in global health when developing global health curricula.

Introduction

Residency programs and medical schools are increasingly offering global health experiences to their trainees.1–3 Going forward, many global health advocates recommend continued expansion of global health education for trainees.4–7 To be sure, these experiences provide many educational benefits to the trainee, such as improvement of physical exam skills, and may even increase the chances of pursuing a career in primary care or practicing in an underserved area.8–12 However, there are ethical concerns about how the host institution and the patients benefit from trainees providing care.13–16 In addition, providing these experiences requires program directors to navigate the logistics of graduate medical education financing, accreditation restrictions, and the need for a call-free time period.

Given the significant resources required to plan and fund these experiences and the potential ethical concerns, it is important to understand the purpose of these rotations. For some trainees, especially those who plan to pursue global health careers, international rotations could provide training in essential global health competencies.17,18 The need for health care providers trained to provide care in resource-poor countries was highlighted by the 2010 Haiti earthquake and other recent catastrophes.19 Alternatively, for trainees who do not plan to spend significant time abroad in the future, international rotations may serve as “medical tourism.”20 To understand the role of international experiences in residency, it is essential to assess residents' interest in a global health career.

Previous studies demonstrate that resident interest in participating in international health rotations during training is high and may influence choice of training sites.1,10,11,21–26 However, studies of resident interest in global health experiences have not asked about career intentions in global health work and whether the interest in global health translates into plans to pursue a global health career. Prior studies have been single-specialty and mostly single-site focused, and it is unclear if the results are representative of a broader resident population. Last, it is uncertain if the financial, scheduling, and family obligations described as barriers to participation in international health experiences apply to a broader sample of residents and whether perceptions of barriers are influenced by future career interests.

This study aimed to describe interest in and perceived barriers to global health experiences during residency training for a broad group of interns and to examine how these factors related to future career plans.

Methods

Data Collection

We created an anonymous survey to assess interest in global health experiences during residency training, barriers to participation, and interest in a global health career, with questions based on previous studies of global health interest.1,10,11,21–26 Sections asked respondents to (1) report previous international experiences; (2) rank the likelihood (on a scale from 1, “very unlikely,” to 5, “very likely”) of participating in a global health experience if they had to use vacation time or had to personally finance the experience; (3) identify barriers to participation in a global health experience (prompting respondents to indicate if finance, schedule, family obligations, or personal safety were factors); and (4) rate their likelihood of having a career focused on global health and indicate the expected proportion of time spent abroad devoted to a global health career (consisting of the responses: none, occasional short [<4-week] experiences, part-time, or full-time).

The survey questions constituted 1 page of a 2-page survey. The other page was a survey of resident duty hours. The survey was distributed to all incoming interns at 3 hospitals affiliated with 2 Midwestern US medical schools during graduate medical education orientation in June 2009. It was distributed in paper form at 2 sites and administered electronically at a third site. A trained research assistant entered the data from the paper surveys and merged it with the electronic survey data into an electronic spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft, Bellvue, WA) and de-identified the data using a numerical code to indicate the teaching site. To preserve anonymity, we obtained only medical school and specialty data from participants. This research was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine interest in global health and to identify barriers to participation. To characterize those who planned to pursue a future career in global health, we defined interns with a committed interest in global health as those planning to spend part-time or full-time abroad as part of a global health career. Preferences of the interns with a committed interest in global health were compared to those of all other interns. A subset analysis was conducted to compare the preferences of interns with a committed interest in global health to those of interns interested in global health but planning only occasional travel. Chi-square analysis was used to test differences between preferences reported as dichotomous, while the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for preferences reported as ordinal responses. P values of less than .05 were used to denote statistical significance. Site-adjusted ANOVA was also performed to control for site differences.

Results

Overall, 299 of 345 interns (87%) responded to the survey. Response rates did differ by site (site 1, 90%; site 2, 98%; site 3, 80%; P < .001). The interns who entered training at these sites graduated from 103 medical schools and represented 21 specialties. Nearly half the interns (48%) reported prior participation in a global health activity that included the following experiences: clinical rotation, 29%; volunteer, 21%; and research, 10%.

Almost half of the incoming interns (45%) would participate in an experience during residency if it required using vacation time, yet fewer (31%) would participate if it required personally financing the experience. Almost all interns (98%) reported at least one barrier to participating in a global health experience, with scheduling (82%) and financial (80%) concerns reported most often. Family obligations (45%) and personal safety (23%) were mentioned less often.

Roughly two-thirds (65%) of the interns stated they were somewhat or very likely to focus on global health in their future careers, and of these, 77% of interns reported interest in participating in short, occasional trips, while 23% of interns intended to pursue a part-time or full-time career abroad. We defined the latter group as interns committed to a career in global health abroad.

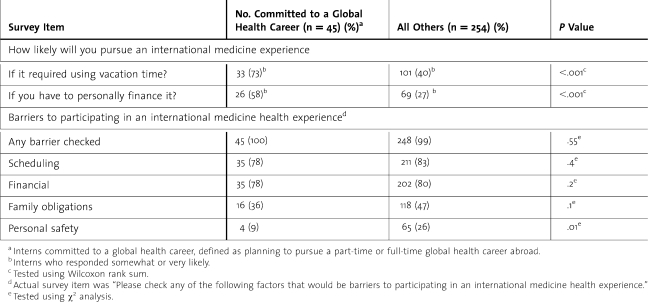

Comparing interns committed to a global health career abroad to all other interns revealed several differences. First, interns committed to part-time or full-time careers abroad reported having more past experiences in global health (82% vs. 43% of all others, respectively; P < .001), being more likely to use vacation time (73% vs. 40% of all others, respectively; P < .001), being more likely to personally finance a trip (58% vs. 27% of all others, respectively; P = <.001), and were less concerned about personal safety (9% vs. 26% of all others, respectively; P = .01). There were no differences in factors such as family obligations, financial concerns, or scheduling concerns as barriers between those interns committed to a career in global health and the remainder of interns (table).

Table.

Incoming Interns‚ Self-Reported Barriers To Participating In A Global Health Experience During Residency (n = 299)

To further characterize interns committed to a global health career abroad, we compared the interns committed to a career abroad to those interested in international health but only planning occasional travel. Several differences in preferences were revealed by this analysis. First, interns committed to a global health career abroad reported having more past experiences in global health than those interested in only occasional travel (committed, 84%, vs. occasional, 55%; P < .001); and second, they reported being more likely to use vacation time (committed, 75%, vs. occasional, 55%; P < .001) or to personally finance an experience (committed, 59%, vs. occasional, 40%; P = .02) than those interested in only occasional travel. While not statistically significant, interns committed to a global health career abroad reported less concern about personal safety than those interested in occasional travel (committed, 9%, vs. occasional, 23%: P = .052). Again, there were no differences in reporting family obligations, financial concerns, or scheduling concerns as barriers between those interns committed to a global health career and those interested in occasional travel.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multisite, multispecialty study relating residents' interest in global health during training to their future careers. Similar to previous studies, we observed the high prevalence of scheduling and financial concerns as barriers to resident participation in global health experiences.1,10,21–23 In contrast to previous studies, family obligations were less frequently reported as a barrier to participation.

Our findings identified 2 distinct groups of interns interested in global health: the occasional travelers who were interested in short rotations abroad and those committed to significant time abroad who had had more global health experiences prior to residency and were more willing to make sacrifices to obtain additional global health training. It is important to note that interns committed to a global health career with substantial time abroad represent 15% of all interns surveyed.

This study has several implications regarding global health education for medical schools and teaching hospitals. Given the high prevalence of financial concerns as a barrier reported by all interns, funding for short-term experiences and debt forgiveness for careers in global health may be important to facilitate participation in global health work. Because international rotations are costly to set up, medical educators could acknowledge preferences in global health career plans when developing curricula and directing funding. One could envision 2 global health education tracks offered to incoming interns based on past experiences and career interests in global health. Interns committed to a global health career would benefit from formal training abroad to build on their knowledge from previous experiences. Although this group was more willing to finance global health experiences, funding their global health training could help distinguish their global health education as professional development for future careers, contrasted with a “paid holiday.”27 These experiences could prepare and inspire residents to pursue immersive global health experiences after residency, such as the National Institutes of Health Fogarty Fellowship or Médecins Sans Frontière.4 The occasional travel group would benefit from a US site global health experience, such as a travel medicine clinic or a clinic serving recently immigrated patients, to learn more about global health and inform a possible future career choice. Alternatively, they could consider travel as part of a service learning opportunity, such as trips sponsored by religious organizations. Our study has several limitations, including a sample of interns from 3 midwestern hospitals, which may limit generalizability. The interns in our study reported having more global health experiences than was reported in the 2009 Association of American Medical Colleges report,28 which may partly explain the larger number of interns interested in a global health career. Second, we assessed intern perceptions prior to the start of internship, and it is possible that interest in global health may change with clinical experience during residency. Future studies should explore trainees' perceptions about what a global health career entails, and trainee interest in global health careers is increasing, and how this interest changes from medical school through residency. To foster generalizability of the results, future studies should use a national sample of interns, with the ultimate aim of developing relevant and cost-effective curricula and experiences that provide the most appropriate education to match residents' level of interest in global health.

Conclusions

A sizable percentage of incoming interns express great interest in global health overall, but fewer interns plan to pursue a global health career abroad. For interns who are unsure of their commitment to global health, career counseling and in-country work can be helpful in informing their career decision. Residents committed to a career abroad would likely benefit from being identified early and provided with appropriate training opportunities.

Footnotes

Jonathan M. Birnberg, MD, is a Fellow in general internal medicine at the University of Chicago; Monica Lypson, MD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine and Assistant Dean for Graduate Medical Education, University of Michigan; R. Andy Anderson, MD, is Clinical Professor in the Department of Medicine and Program Director of Internal Medicine Residency, North Shore University Health System; Christian Theodosis, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Chicago; Jimin Kim, MSc, is a postbaccalaureate student at Goucher College; Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MD, is the Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Medicine and Associate Dean for Global Health, University of Chicago; and Vineet M. Arora MD, MAPP, is Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, Associate Director of Internal Medicine Residency, and Assistant Dean for Scholarship and Discovery at the Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago.

Funding: Dr. Birnberg reports receiving a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); however, this funding source had no role in the current study. Dr. Birnberg has received funding from the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Arora has received funding from the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, AHRQ, and National Institute on Aging.

Dr. Birnberg presented this material at the Regional Midwest Meeting for the Society for General Internal Medicine, Chicago, IL, September 2009, and at the 33rd Annual Meeting for the Society for General Internal Medicine, Minneapolis, MN, April 2010. The authors thank Meryl Prochaska, BA, Barry Kamin, MS, Holly Humphrey, MD, and Michael Simon, MD, University of Chicago, and Sarah Middlemas, University of Michigan, for their assistance with survey administration.

References

- 1.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. Mar 2009;84(3):320–325. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181970a37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jayaraman SP, Ayzengart AL, Goetz LH, Ozgediz D, Farmer DL. Global health in general surgery residency: a national survey. J Am Coll Surg. Mar 2009;208(3):426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jense RJ, Howe CR, Bransford RJ, Wagner TA, Dunbar PJ. University of Washington orthopedic resident experience and interest in developing an international humanitarian rotation. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) Jan 2009;38(1):E18–E20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. Sep 2000;32(8):566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houpt ER, Pearson RD, Hall TL. Three domains of competency in global health education: recommendations for all medical students. Acad Med. Mar 2007;82(3):222–225. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305c10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanton B, Huang CC, Armstrong RW, et al. Global health training for pediatric residents. Pediatr Ann. Dec 2008;37(12):786–792. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20081201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grudzen CR, Legome E. Loss of international medical experiences: knowledge, attitudes and skills at risk. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. Mar 2003;78(3):342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawatsky AP, Rosenman DJ, Merry SP, McDonald FS. Eight years of the mayo international health program: what an international elective adds to resident education. Mayo Clin Proc. Aug 2010;85(8):734–741. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta AR, Wells CK, Horwitz RI, Bia FJ, Barry M. The International Health Program: the fifteen-year experience with Yale University's Internal Medicine Residency Program. Am J Trop Med Hyg. Dec 1999;61(6):1019–1023. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haskell A, Rovinsky D, Brown HK, Coughlin RR. The University of California at San Francisco international orthopaedic elective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Mar 2002;(396):12–18. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey AH, Haq C, Gjerde CL, Rothenberg D. Career influence of an international health experience during medical school. Fam Med. Jun 2004;36(6):412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crump JA, Sugarman J. Ethical considerations for short-term experiences by trainees in global health. JAMA. Sep 24 2008;300(12):1456–1458. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey KM. International surgical electives: reflections in ethics. Arch Surg. Jan 2008;143(1):10–11. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsey KM, Weijer C. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg. Nov 2007;31(11):2067–2070. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingham TP, Muyco A, Kushner A. Surgical elective in a developing country: ethics and utility. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(2):59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):226–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdick WP, Hauswald M, Iserson KV. International emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(7):758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerry V. And one for doctors, too. New York Times. February 13, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrosoniak A, McCarthy A, Varpio L. International health electives: thematic results of student and professional interviews. Med Educ. 2010;44(7):683–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell AC, Casey K, Liewehr DJ, Hayanga A, James TA, Cherr GS. Results of a national survey of surgical resident interest in international experience, electives, and volunteerism. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(2):304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell AC, Mueller C, Kingham P, Berman R, Pachter HL, Hopkins MA. International experience, electives, and volunteerism in surgical training: a survey of resident interest. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(1):162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WC, Corey GR, Lallinger GJ, Durack DT. International health and internal medicine residency training: the Duke University experience. Am J Med. 1995;99(3):291–297. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dey CC, Grabowski JG, Gebreyes K, Hsu E, VanRooyen MJ. Influence of international emergency medicine opportunities on residency program selection. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(7):679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Federico SG, Zachar PA, Oravec CM, Mandler T, Goldson E, Brown J. A successful international child health elective: the University of Colorado Department of Pediatrics' experience. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(2):191–196. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozgediz D, Roayaie K, Debas H, Schecter W, Farmer D. Surgery in developing countries: essential training in residency. Arch Surg. 2005;140(8):795–800. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Are C. Global health training for residents. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1171–1172. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17acf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.AAMC. 2009. Association of American Medical Colleges GQ Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: All Schools Summary Report. https://www.aamc.org/download/90054/data/gqfinalreport2009.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2011. [Google Scholar]