Abstract

Background

This study examined the determinants of specialty choice of preresidency medical graduates in southeastern Nigeria.

Methods

We used a comparative cross-sectional survey of preresidency medical graduates who took the Basic Sciences Examination of the Postgraduate Medical College in Enugu, southeastern Nigeria, in March 2007. Data on participants' demographics and specialty selected, the timing of the decision, and factors in specialty selection were collected using a questionnaire. Data were examined using descriptive and analytical statistics. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

The survey response rate was 90.8% (287 of 316). The sample included 219 men and 68 women, ranging in age from 24 to 53 years and with a mean age of 33.5 ± 1.1 (SD) years. Career choice was more frequently influenced by personal interest (66.6%), career prospects (9.1%), and appraisal of own skills/aptitudes (5.6%), and it was least affected by altruistic motives (1.7%) and influence of parents/relations (1.7%). The respondents selected specialties at different rates: obstetrics and gynecology (22.6%), surgery (19.6%), pediatrics (16.0%), anesthesiology (3.1%), psychiatry (0.3%), and dentistry (0.0%). Most (97.2%) participants had decided on specialty choice by the end of their fifth (of a total 16 years) postgraduate year. The participants significantly more frequently preferred surgery and pediatrics to other disciplines (P < .002, after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons).

Conclusions

Preresidency medical graduates in southeastern Nigeria were influenced by personal interest, career prospects, and personal skills/aptitude in deciding which specialty training to pursue. The most frequently chosen specialties were surgery and pediatrics. These findings have implications for Nigeria's education and health care policy makers.

Editor's note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument used in this study (103KB, doc) .

Introduction

The availability of an appropriately trained and motivated health workforce with a balanced specialty distribution is critical for the capacity of a health system to meet the needs of its population.1 In addition, the medical specialist workforce provides education, conducts research, and contributes to health policy formulation and the implementation of health care programs.2–4 Physician specialty choice is a multidimensional process. Accurate mapping of the factors determining specialty choice is important to develop interventions aimed at influencing career choices.

Nigeria, like other developing countries, has a specialty maldistribution of the medical workforce.5 The clinical specialties of internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology are frequently chosen at the expense of other medical and surgical specialties and community medicine/public health. This has remained a recurrent finding in several studies of the selection patterns of Nigerian medical students.6–9 Nigeria's medical workforce also has an urban-rural maldistribution. The need for specialist medical care to satisfy the population's health care needs is growing, and the maldistribution has adverse implications for availability and affordability of comprehensive health services, and may create barriers to access specialist care. Understanding the dynamics of specialist career decisions is critical to efforts to modulate the career aspirations of medical graduates to meet specialist workforce needs.10–12

Medical training in Nigeria is a 6-year program, comprising 2 preclinical years and 4 years of education in clinical medicine. Medical school is followed by a 1-year mandatory rotational medical internship and 1 year of National Youth Service; both years are required before individuals can qualify for physician employment or enrollment in a specialty training program. After these mandatory 2 years, many medical graduates work briefly in the private or public health sector for financial reasons, prior to seeking a specialist training program (residency).

During residency training, candidates sequentially complete the Primary (Basic Sciences), Part I, and Part II (final) examinations administered by the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria (NPGMCN) and the West African Postgraduate Medical College. Previous studies of the determinants of medical specialty choice in Nigeria entailed mostly surveys of medical students,6–9 and medical interns, with few studies of residents and postinternship, preresidency medical graduates.5,13–16

Our study examines the factors influencing the specialty choice of preresidency medical graduates in southeastern Nigeria, with the aim of examining if the determinants of specialty choice remain the same after completion of medical school and internship.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of preresidency medical graduates (postinternship medical graduates who have not yet enrolled in residency training). Our cohort encompassed individuals who took the primary (Basic Sciences) examination in southeastern Nigeria in March 2007. We used a structured, open-ended, self-administered questionnaire to collect data on participants' age, sex, marital status, and time since graduation from medical school, along with data on specialty choice, timing of this decision, and factors that significantly affected their choice.

The questionnaire was adapted from a study of factors influencing specialty choice by Harris et al17 and was modified using input from a focus group comprising 20 potential study participants drawn randomly from a pool of eligible preresidency medical graduates, interns, and medical officers with specialist career plans. Focus group participants were excluded from participation in the final study.

Prior to deployment, the construct validity and psychometric reliability of the questionnaire were assessed through a pretest on a cohort of preresidency medical graduates. The questionnaire underwent structural modifications and other revisions before it was administered to the cohort of preresidency graduates.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive and analytical statistics were calculated.

Tests for significant interclass differences were performed using χ2, Fisher exact t test, and Student t test. Because the study entailed multiple comparisons, use of the Bonferroni adjustment reduced the level of significance to < .002.

The questionnaire asked participants to rate the contributions of factors on their specialty choice. A factor was considered to contribute if it was rated 3 or above on a 5-point Likert scale,18,19 (graded 0, for not at all, to 4, for highly contributory) by most participants. Scores of 2 or lower were designated noncontributory factors.

Prior to commencement of the study, ethical clearance was sought and obtained from the Ethical Committee of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, and the NPGMCN.

Results

Of 316 candidates who registered for the March 2007 primary (Basic Sciences) examination, 10 were absent, and 9 declined participation in the study. The remaining 297 candidates were enrolled in the study. Participants who did not respond to most questions had their data excluded from the analysis. The final sample comprised 287 candidates (a 90.8% response rate) and included 219 men (76.3%) and 68 women (23.7%). Participants ranged in age from 24 to 53 years, with a mean age of 33.5 years and a modal age group of 31 to 40 years. Their marital status by sex revealed that men tended to be single (144 versus 75; P < .028), whereas women were likely to be married (38 versus 30; P < .042).

Most participants (67.2%) had graduated from medical school in the past 5 years, 72 (25.1%) in the past 6 to 10 years, and 22 (7.7%) more than 10 years earlier. The core clinical specialties (n = 191; 66.6%), comprising obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, pediatrics, and internal medicine, were more frequently preferred to other specialties (n = 96; 33.4%). The distribution of participants by specialty is shown in table 1. Significantly more men selected surgery (P < .001), whereas women predominantly chose pediatrics (P < .001) and community medicine (preventive health; P < .048). Choices of obstetrics and gynecology for men and community medicine (preventive health) for women were notable but did not reach statistical significance. Sex differences in other specialties were not statistically significant.

Table 1.

Distribution of Specialty Choice by Sex

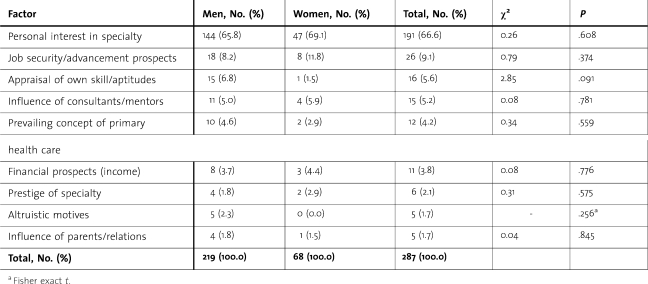

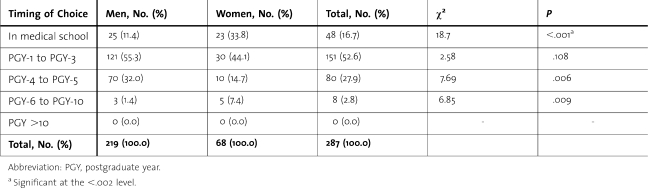

Participant's personal interest in specialty (n = 191; 66.6%) and job security/advancement prospects (n = 26; 9.1%) were the leading determinants of specialty choice. In contrast, altruistic motives (n = 5; 1.7%), influence of parents and relations (n = 5; 1.7%) and appraisal of prestige of specialty (n = 6; 2.1%) had a minimal influence on specialty choice (table 2). Most of the participants (97.2%) had made a decision on specialty choice by the end of their fifth postgraduate year. Compared with men, women tended to choose a specialist career earlier, either in the medical school or before the end of postgraduate year 3. The timing of the decision on specialty choice is shown in table 3.

Table 2.

Factors Affecting Specialty Choice

Table 3.

Timing of Decision on Specialty Choice

Discussion

The high proportion of men found in this study is similar to previous Nigerian studies13 and those in other developing nations,13 but it differs from many developed nations.20 It has been suggested that this sex imbalance may be caused by rigidity in medical training programs and sex-based discrimination.21

The 31- to 40-year modal age group in the present study is similar to that in previous reports in Nigeria5 and America,22 and reflects both disruption in the educational process and the current practice of most graduates working in the private or public health sector to attain financial stability before enrolling in a specialist training program.

The spectrum of career choice was biased in favor of clinical specialties. Additionally, women were underrepresented in all specialties and significantly underrepresented in surgery and, to a lesser degree, obstetrics and gynecology. This corroborates previous reports in Nigeria,5,13,23 and elsewhere.24–28 The sophisticated referral teaching hospitals, which dominate undergraduate training and which place a disproportionate emphasis on clinical disciplines and disease-focused philosophies, likely influence medical student choices. In addition, the prospect of extra income from a dual clinical practice (working in the public and private health sectors simultaneously) likely is a factor in the observed specialty selection pattern. Personal interest in specialty, career prospects, and appraisal of one's own skills and aptitude were the leading determinants of participants' career choice, with interest far outweighing the influence of the other factors. The general patterns of influences on specialty career choice echo previous reports,13,15,20,26 including the lower appeal of surgery to women.28 Despite these sex-specific differences in specialty choice, there were no differences by sex in the factors that influenced specialty choice. Absence of sex differences in factors influencing specialty choice in this study is at variance with the findings by Harris et al17 and prior surveys in Nigeria.5,13 This may be partially explained by the female sex dominance and low response rate for Harris et al,17 and the lack of between-sex comparisons in previous Nigerian surveys. For overall specialty choice, the comparatively longer undergraduate clinical exposure to the core clinical specialties may reinforce participants' preexisting affinities for these specialties. Finally, it is possible that sex-neutral external influences affected respondents' personal interest in a specialty, the leading determinant of career choice in our survey.

Most respondents had made a decision on specialty choice by the end of their fifth postgraduate year, with women deciding even earlier than men. The observed timing of decision on specialty choice is generally consistent with other studies.17,29,30 This strengthens the case for interventions early in medical school, to influence specialty selection for both sexes.

This study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional, single-site, and single-assessment design. Future studies should investigate candidates early in medical school to evaluate the factors that influence career choices, and follow students longitudinally to determine the stability of these choices.

Conclusion

The specialty choice of preresidency medical graduates in southeastern Nigeria shows a distribution of specialty choice that favors core clinical specialties. Personal interest in the specialty was the predominant factor that influenced most individuals, and most individuals chose a specialty before the end of their fifth postgraduate year. The study found sex differences in specialty choice and timing of choice, but not in the factors influencing the choice. Our findings have implications for the provision of comprehensive specialty health care in Nigeria. It suggests a need for medical educators to offer enhanced career guidance and to review specialist training curricula to eliminate sex-based obstacles to specialist career choices.

Footnotes

All authors are from the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu, Nigeria. Boniface Ikenna Eze, FMCOphth, FWACS, is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Ophthalmology; Onochie Ike Okoye, FMCOphth, is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Ophthalmology; Ferdinand Chinedu Maduka-Okafor, FMCOphth, is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Ophthalmology; and Emmanuel Nwabueze Aguwa, FMCPH, FWACP, is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Community Medicine & Public Health.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the invigilators at the Enugu Centre of the March 2007 Primary Fellowship examination of the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria during the collection of data for this work.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Kleczkowaski BM, Elling RH, Smith DL. Health system support for primary health care: a study based on the technical discussions held during the 34th World Health Assembly, 1981. Public Health Pap. 1984;80:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Federal Ministry of Health. National Health Policy and Strategy to Achieve Health for All Nigerians. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 1996. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muula AS, Komolafe OO. Specialisation pattern of medical graduates, University of Malawi College of Medicine, Blantyre. Cent Afr J Med. 2002;48((1–2)):14–17. doi: 10.4314/cajm.v48i1.8418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Jarallah KF, Moussa MA. Specialty choices of Kuwaiti medical graduates during the last three decades. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(2):94–100. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bojuwoye BJ, Araoye MO, Katibi IA. Factors influencing specialty choice among medical practitioners in Kwara state, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 1998;48((1–3)):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Odusanya OO, Alakija W, Akesode FA. Socio demographic profile and career aspirations of medical students in a new medical school. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2000;7(3):112–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohaeri JU, Akinyinka OO, Asuzu MC. The specialty choice of clinical year students at the Ibadan Medical School. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1992;21(2):101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oyebola DD, Adewoye OE. Preference of preclinical medical students for medical specialties and the basic sciences. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1988;27(3):209–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojo OS, Afolabi ERI. Social issues in medicine: an evaluation of determinants of medical manpower resource. Orient J Med. 1992;4:15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrides DV, McManus IC. Mapping medical careers: questionnaire assessment of career preference in medical school and final year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland JL. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Careers. New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyler H. Parental role models, gender and education choice. Br J Sociol. 1998;49:375–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogbonnaya LU, Agu AP, Nwonwu EU, Ogbonnaya CE. Specialty choice of residents in the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu 1989–1999. Orient J Med. 2004;16(3):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibe BC, Nkangieme KEO. Career preference of young doctors qualifying in Nigeria, 1985/86. Niger Med Pract. 1988;4(3):23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odusanya OO, Nwawolo CC. Career aspiration of house officers in Lagos, Nigeria. Med Educ. 2001;35(5):482–487. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohaeri JU, Akinyinka OO, Asuzu MC. The specialty choice of interns at Ibadan General Hospitals. West Afr J Med. 1993;12(2):78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris MG, Gavel PH, Young JR. Factors influencing the choice of specialty of Australian medical graduates. Med J Aust. 2005;183(6):295–300. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Likert RA. Technology for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 2002;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jameison S. Likert Scale: how to (ab) use them. Med Educ. 2004;38:1212–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Abel T, Buddeberg C. Swiss residents specialty choices- impact of gender, personality traits, career motivation and life goals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:136–144. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed V, Buddeberg-Fischer B. Career obstacles for women in medicine: an overview. Med Educ. 2001;35(2):139–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crutcher RA, Banner SR, Szafran O, Watanabe M. Characteristics of international medical graduates who applied to the CaRMs 2002 match. CMAJ. 2003;168(9):1119–1123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Bulletin of the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria. 1999;No 7:20. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szafran O, Crutcher RA, Banner SR, Watanabe M. Canadian and immigrant international medical graduates. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1242–1243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G. Career choice of UK medical graduates of 2002: questionnaire survey. Med Educ. 2006;40(6):514–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zarkovic A, Child S, Naden G. Career choice of New Zealand Junior doctors. N Z Med J. 2006;119(1129):U1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Increasing the Relevance of Education for Health Professionals. A Report of WHO Study Group on Problem-Solving Education for the Health Professionals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1993. Tech Rep Ser No. 838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson HC, Redfern N. Why do women reject surgical careers. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(suppl):290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson JM, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. Career pathways and destinations 18 years on among doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1977: Postal Questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1988;317:1425–1428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Stability and change in career choice of junior doctors: Postal Questionnaire survey of UK qualifiers of 2003. Med Educ. 2000;34((a)):700–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]