Abstract

Background

Emergency medicine residents are expected to master 6 competencies that include clinical and leadership skills. To date, studies have focused primarily on teaching strategies, for example, what attending physicians should do to help residents learn. Residents' own contributions to the learning process remain largely unexplored. The purpose of this study was to explore what emergency medicine residents believe helps them learn the skills required for practice in the emergency department.

Methods

This qualitative study used semistructured interviews with emergency medicine residents at a major academic medical center. Twelve residents participated, and 11 additional residents formed a validation group. We used phenomenologic techniques to guide the data analysis and techniques such as triangulation and member checks to ensure the validity of the findings.

Results

We found major differences in the strategies residents used to learn clinical versus leadership skills. Clinical skill learning was approached with rigor and involved a large number of other physicians, while leadership skill learning was unplanned and largely relied on nursing personnel. In addition, with each type of skills, different aspects of the residents' personalities, motivation, and past nonclinical experiences supported or challenged their learning process.

Conclusion

The approaches to learning leadership skills are not well developed among emergency medicine residents and result in a narrow perspective on leadership. This may be because of the lack of formal leadership training in medical school and residency, or it may reflect assumptions regarding how leadership skills develop. Substantial opportunity exists for enhancing emergency medicine residents' learning of leadership skills as well as the teaching of these skills by the attending physicians and nurses who facilitate their learning.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the interview guide (24.5KB, doc) used in this study.

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) identifies 6 competencies for emergency medicine (EM) residents. In addition to clinical skills, 5 areas (patient care, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice) include leadership requirements such as decision making, effective communication, collaboration, and team leadership.1

Emergency departments (EDs) provide mixed conditions for mastering clinical and leadership competencies. The ED is a rich learning environment because of the volume and variety of undifferentiated patients and many experienced professionals from whom to learn.2,3 At the same time, learning may be challenging owing to the unpredictable workload, limited time for high-quality discussions, and frequent interruptions.2,4,5

Research on how EM residents acquire clinical and leadership skills is limited. Studies have focused on clinical skill teaching by EM physicians and often include residents in many specialties and medical students, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding EM residents' learning.2,4–7 Consistent with the apprenticeship perspective of teaching, studies recommend that faculty plan teaching sessions and be positive about teaching and also tailor teaching to the learner's abilities, with some challenge and feedback.2,4,6–8 Apprenticeship teaching also ignores the contemporary view that learning is optimal when the learner is performing tasks in different contexts and interacts with many diverse individuals.9–11 Recent challenges to medical education call for pedagogies that encourage learners' own discovery, promote dialogue, and involve reflection.12 This study reports on specific learning experiences and practices that EM residents perceive as helping them gain the skills they believe are required to practice in the ED.

Methods

We used qualitative phenomenologic interview methods to gain insight into the residents' perspectives of their learning process in the ED.13 The research team included 3 nonphysician educators (E.F.G., C.L.T., M.M.P.) and 2 EM physicians (C.N.R., J.P.S.). The site was an emergency medicine program at an academic medical center. Emergency medicine residents rotate through 3 EDs: an urban hospital seeing greater than 60 000 visits annually and 2 suburban hospitals seeing from 40 000 to 80 000 visits annually. Most of the residents' time is spent in the urban location with a care team of ED nurses and other professionals overseen by an attending physician.

Emergency medicine residents were contacted by e-mail and provided a description of the study at an ED meeting by a nonphysician educator (E.F.G.). No faculty members were present. Residents from all 3 years were invited to participate. Twelve of 27 (44%) volunteered (including 6 second-year, 4 third-year, and 2 fourth-year residents), consistent with the number of participants recommended for phenomenologic studies.13 All participants consented to have their interviews audiotaped and used for research purposes.

Two nonphysician educators (E.F.G., C.L.T.) conducted individual interviews (60–90 minutes each) in an office outside the ED. A semistructured interview guide pilot-tested on 2 EM residents was used13 (provided as online supplemental material). Questions were provided in advance to facilitate personal reflection and help focus interview time. Identification of EM practice requirements and definitions of learning were left to the participants so as not to bias their responses. The interview data were deidentified and transcribed verbatim. The study received Institutional Review Board approval.

Data analysis was completed by the 3 nonphysician educators. Phenomenologic techniques guided data analysis.14 Two transcripts were reviewed by the 3 nonphysician educators working collectively to identify and cluster statements of significance, leading to the creation of codes. The coding schema was applied to the remaining transcripts by the 2 nonphysician educators (E.F.G. and C.L.T. each coding the other's interviews), while the third (M.M.P.) checked for coding consistency. Coded statements were grouped into categories by the 3 nonphysician educators working collectively. Discussion of category content led to the identification of themes (ie, learning triggers, strategies, challenges, supports).10,11 Representative quotes were identified and the experience summarized. The 2 EM physician team members reviewed the data to ensure credibility of interpretation. The findings were presented to EM residents at grand rounds (23 of 27 attended) as a form of member checks.15 Residents provided anonymous written comments confirming the accuracy of the results.

Additional procedures to ensure trustworthiness included (1) triangulation of data collection and analysis by using multiple researchers; (2) purposive sampling for diverse perspectives; (3) peer debriefing after initial interviews; (4) peer review of the initial transcripts for evidence of leading or ignoring participants' comments; (5) sufficient data collection to ensure saturation; and (6) use of peer reviewers and devil's advocates in code checking and presentation of findings.15 Quotes are provided to allow others to determine the extent to which the findings are transferable.

Results

The residents distinguished EM from other specialties by its leadership-related requirements:

In the [ED] environment, many different things can be coming at you at once—other specialties might have 20 patients on a floor, but they're dealing with 1 at a time…and the pace seems to take place over days instead of minutes to hours….You need to figure out what needs to be done right away and what can wait 5 minutes or half an hour.

…you can run into roadblocks if you don't keep check of your tech, what they're doing, what you're ordering, your nurses, and make sure they are on the same page.

EM residents identified 9 leadership skills for ED practice: prioritizing, organizing, managing, multitasking, communicating, decision making, being adaptable, being assertive, and having emotional resiliency. They indicated these were the most difficult to learn:

The hardest thing that I've had to learn is leadership in the ED and managerial skills…because it's not really explicitly taught at any point…even though you're in an environment where you're suddenly thrust into the position where you're managing people.

Learning Triggers

Learning clinical and leadership skills was initiated by similar experiences: actual practice, challenging cases, mistakes, and discussion with the attending physician. Having significant responsibility was key to triggering residents' learning; however, the nature of the responsibility varied. Being forced to specify a treatment plan by oneself was critical to learning clinical skills:

The best thing is when [the attending does not] give you the plan and they say, ‘Well, what do you want to do and why?’…then you have to come up with a plan…if they disagree with your plan, you explore why they disagree.

In contrast, learning leadership skills was triggered by the needs of others:

….you've got 8 or 10 patients and a lot of people asking you for stuff at the same time…patients who want certain things…nurses who want certain things; the triage nurse who wants certain things; the attending physician who wants certain things; admitting physicians who want certain things done—and just out of the process of people being happy or mad at you, you figure out what's important to get done.

Learning Strategies

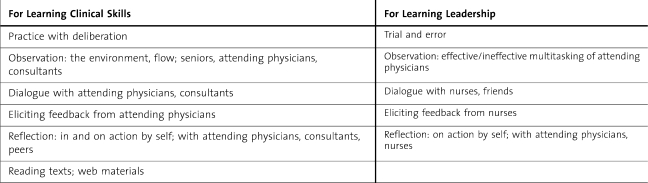

Significant differences were found regarding the strategies that EM residents used to learn clinical versus leadership skills. A wide range of strategies were used but executed differently (table 1). Learning clinical skills was approached with rigor; involved senior residents, attending and consulting physicians, and peers; and took place constantly:

Table 1.

Key Learning Strategies

….it's basically dependent on my intentionality of doing it…it's really dependent on how much I put into it or what I do with the time and experiences I have that will result in learning…I'm the one who has to ask the questions. I'm the one who has to make the time to read about something. I'm the one who has to make sure I'm teaching the medical students because no one is going to force me to learn in the ED…the main factor is really self-motivation.

In contrast, residents identified few intentional instances for learning leadership skills. Comments indicated that learning leadership skills was “basically trial and error.” Observation and reflection were used only with attending physicians:

[You] compare and contrast…who do you want to do [multitasking] like; who do you not want to do it like.

From reviewing what happened with the attending, we agreed that the biggest mistake was just not communicating with the nurses effectively.

Comments revealed nurses to be prime learning facilitators:

Certainly there are some great nurses that I'm able to dialogue about especially management issues and help me explain what I'm doing.

If I made a mistake or did something to interrupt the flow…I ask if [nursing] would like me to do this differently…do something differently to help them from their point of view.

Several residents indicated that as they “moved further along” they used conversation and introspection to develop leadership skills. This led to realizations:

[I was] not utilizing the team as much as I could have….[I] need to be better about communicating with the staff….learn how to create dialogue.

Unlike clinical skills, no mention was made of accessing literature to learn about leadership skills.

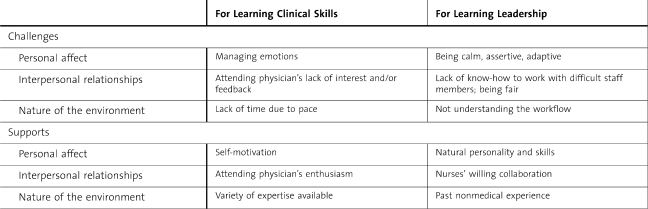

Learning Challenges and Supports

Emergency medicine residents identified issues related to themselves, their relationships with others, and the environment as challenging and supportive to their learning (table 2).

Table 2.

Key Challenges and Supports for Learning

Residents reported that it was challenging to learn to manage their emotions and still perform their work:

You can end up going through some pretty hard emotional things because you can't stop doing your job to recover. You have to continue seeing patients….

Learning leadership skills also required calmness, but in addition, a change in demeanor:

I had to learn when to be assertive. Especially at the beginning, I erred too much on the side of not being assertive enough.

Residents reported that lack of time or feedback from attending physicians made it challenging to learn clinical skills:

The biggest challenge because there's so much going on [is] to slow down and realize it's going to take more time but I need to learn this procedure well—that's the biggest barrier to learning.

Lack of education or prior experience in handling difficult staff members made it challenging to learn leadership skills. An additional challenge to learning leadership skills was an incomplete understanding of how things work in the ED:

There's a flow…You have to know who does what, how to get things done…That is challenging for anybody coming in new.

Emergency medicine residents' clinical learning was largely supported by self-motivation and facilitated by attending physicians, while the supports described for learning leadership skills highlighted nurses as key facilitators and pointed to EM residents' reliance on innate abilities and past work experiences:

I'm efficient by nature. I'm a multitasker by nature.

I was in combat… more intense situations than anything the ED can throw at me. I led a platoon…so barking orders, making sure everyone understands is not new to me.

I waited tables…[It's] very similar to being an EM doctor…You have people in different stages of their meals…You need to know who is ready for what—figure out what happens next and get it done in a timely fashion…Multitasking is an important skill in both professions.

In sum, EM residents' personalities, motivation, and past experiences challenged and supported their learning clinical and leadership skills. Physicians also influenced clinical skill development; nurses aided leadership skill development.

Discussion

The contribution of our study is its assessment of EM residents' perceptions of what is important to practice EM and how those skills are learned. We did not test the effectiveness of individual learning strategies, but those mentioned by the residents are consistent with adult-learning theories,9–11 that advocate engagement, meaningful experience, reflective practice, and contextual influences, and with recommendations for medical education that include discovery, dialogue with team members, and ongoing reflection.12

One may ask why the perceptions of novice learners should direct teaching strategies. The answer is simple: If the learner is not learning, the teaching strategy is not effective. If attending physicians and others understand how EM residents learn, teaching strategies can be adjusted to be more effective.

Our findings indicate that no single teaching strategy is sufficient for learning EM. Considerable independent action by the EM residents is required to identify their learning needs, secure resources, obtain meaningful feedback, and assess their performance; in other words, they need to be self-directed learners.11 Emergency medicine residents in this study used various levels of self-directedness. Exposure to models of self-directed learning, including clearly defining responsibilities of teachers and learners, may enhance learning.

Team and group learning was notably absent from the residents' comments. This is surprising given that work in the ED is done in teams, but it may be because team concepts are not largely being taught in the medical curriculum.12 Emergency medicine residents did learn from different team members, but as a one-to-one occurrence. This suggests benefit in added education about the principles of teamwork.16

Leadership skills generally are not part of the medical school curriculum,12 and it is not surprising that EM residents expressed difficulty learning how to lead. What is surprising is the narrowness of the strategies used to learn leadership skills. As clinical proficiency is considered foundational to a physician's identity,17 EM residents may be honing their clinical skills first. However, the fact that few instances of deliberate learning of leadership skills were identified, combined with the selection of nurses (versus physicians) with whom to discuss leadership, may indicate other possibilities. They include the following assumptions: (1) leadership skills develop over time; (2) leadership is an unspoken topic, part of the “hidden curriculum”; or (3) attending physicians are unaware of how to facilitate the development of leadership skills, perhaps not recognizing such traits in their own practice and not labeling them as leadership. Explicit education of attending physicians and residents in leadership may be needed to promote deliberate feedback to EM residents about leadership skills. Practices used in nonclinical environments, including personal plan identification and implementation followed by coaching and reflection, should be considered.18,19

The EM residents' comments reflected a narrow views of leadership as specific behaviors of being in charge and managing others (ie, giving direction, multitasking, prioritizing, and organizing). Little mention was made of the relational aspects of leadership as a dynamic, interactive, iterative behavior between individuals and within teams.18–21 Emergency medicine residents' views of leadership largely omit the competencies described by the ACGME regarding effective teamwork and team leadership, and openness and responsiveness to feedback from team members.1 Thus, the establishment of a formal curriculum may be warranted and should include exploration of the full range of leadership perspectives. An opportunity for identifying best practices for leadership in the ED may also be indicated.

Strategies used to teach leadership skills need to take into account EM residents' personal traits and past nonclinical experiences, and allow time for residents to develop an understanding of the environment in which they are to lead. Nurses should be formally included in the training. One study in which nurses provided formal feedback about residents' managerial, teamwork, and communication skills showed significant resident improvement.22

Limitations of our study include its small convenience sample, which limits generalizability. Quotations were provided to enhance transferability, residents from all 3 years were included to obtain diverse perspectives, and member checks provided additional validation.15

Future studies are needed to confirm the generalizability and the implications of the results and should address the effectiveness of specific teaching strategies, teaching in different levels of EDs, and how more experienced physicians have learned the requisite skills.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that EM residents use a full range of adult-learning strategies, yet the strategies and supports for learning clinical skills are considerably broader and more deliberate than those for learning leadership skills. There is much opportunity for enhancing the learning practices related to leadership among EM residents by including models of self-directed learning; providing formal training in leadership and teamwork; focusing feedback on leadership skills; sharing best practices; and formally including attending physicians, nurses, and other team members in the learning process.

Footnotes

Ellen F. Goldman, EdD, is Assistant Professor of Human and Organizational Learning at George Washington University Graduate School of Education and Human Development; Margaret M. Plack, PT, EdD, is Interim Senior Associate Dean and Associate Professor of Health Care Sciences at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Colleen N. Roche, MD, is Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; Jeffrey P. Smith, MD, MPH, is Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences; and Catherine L. Turley, EdD, RT(R)(T)ARPT, is Assistant Professor of Clinical Management and Leadership at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Emergency Medicine. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/110emergencymed07012007.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R. Creating effective learning in today's emergency departments: how accomplished teachers get it done. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldman E, Plack MM, Roche C, Smith J, Turley C. Resident learning in the emergency department: a phenomenological study. J Workplace Learn. 2009;21(7):555–574. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penciner R. Clinical teaching in a busy emergency department: strategies for success. Can J Emerg Med Care. 2002;4(4):286–288. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500007545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson V, Pirrie A. Developing professional competence: lessons from the emergency room. Stud Higher Educ. 1999;24(2):211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldeen A, Gisondi M. Bedside teaching in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:860–866. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.03.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thurgur L, Bandiera G, Lee S, Tiberius R. What do emergency medicine learners want from their teachers: a multicenter focus group analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:856–861. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratt D, Arseneau R, Collins J. Reconsidering ‘good teaching’ across the continuum of medical education. J Contin Educ Health. 2001;21(2):70–81. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340210203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Illeris K. How We Learn. New York, NY: Routledge; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merriam S, Caffarella R, Baumgartner L. Learning in Adulthood: A Comprehensive Guide. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke M, Irby D, O'Brien B. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moustakas C. Phenomenological Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levi D. Group Dynamics for Teams. 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slotnick H. How doctors learn: education and learning across the medical-school-to-practice trajectory. Acad Med. 2001;76(10):1013–1026. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antonakis J, Cianciolo A, Sternberg R, editors. The Nature of Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yukl G. Leadership in Organizations. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Northouse C. Leadership. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wheatley M. Leadership and the New Science: Discovering Order in a Chaotic World. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tintinalli J. Evaluation of emergency medicine residents by nurses. Acad Med. 1989;64(1):49–50. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198901000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]