Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies are used to assess resident performance, and recently similar competencies have become an accepted framework for evaluating medical student achievements as well. However, the utility of incorporating the competencies into the resident application has not yet been assessed.

Purpose

The objective of this study was to examine letters of recommendation (LORs) to identify ACGME competency–based themes that might help distinguish the least successful from the most successful residents.

Methods

Residents entering a university-based residency program from 1994 to 2004 were retrospectively evaluated by faculty and ranked in 4 groups according to perceived level of success. Applications from residents in the highest and lowest groups were abstracted. LORs were qualitatively reviewed and analyzed for 9 themes (6 ACGME core competencies and 3 additional performance measures). The mean number of times each theme was mentioned was calculated for each student. Groups were compared using the χ2 test and the Student t test.

Results

Seventy-five residents were eligible for analysis, and 29 residents were ranked in the highest and lowest groups. Baseline demographics and number of LORs did not differ between the two groups. Successful residents had statistically significantly more comments about excellence in the competency areas of patient care, medical knowledge, and interpersonal and communication skills.

Conclusion

LORs can provide useful clues to differentiate between students who are likely to become the least versus the most successful residency program graduates. Greater usage of the ACGME core competencies within LORs may be beneficial.

Background

The screening and selection of applicants into residency programs is an inexact science. Applications include information about candidates' performance in medical school and on standardized examinations, a personal statement, and letters of recommendation (LORs). Numerous studies have evaluated the utility of objective metrics (US Medical Licensing Examination scores, medical school transcript, etc) in predicting an applicant's success and have produced mixed results.1–6 Although LORs are consistently considered important in the resident selection process,7–9 their predictive value is not conclusive.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies have been used in assessing resident performance10 but are not a standardized component of the residency application. Recently, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education endorsed the use of a similar competencies format for the evaluation of medical students.11 The goal of this study is to investigate whether references to performance measures associated with the ACGME competencies within LORs are useful in identifying candidates most likely to succeed in residency education in obstetrics and gynecology.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of residents entering the Johns Hopkins University residency program in obstetrics and gynecology through the National Residency Match Program between 1994 and 2004. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Residents meeting inclusion criteria were independently ranked by the residency program director and the department chair. The evaluators assigned each resident a numeric value between 1 (lowest) and 4 (highest) based on each evaluator's independent assessment of the resident's overall performance. Specifically, the evaluator was asked to respond to the question: “Knowing what you now know about this resident after his/her four years of training, would you select him or her again for admission into the residency program?” Each evaluator was blinded to the other evaluator's ratings as well as to the resident's original residency application. Evaluators were permitted to review the residents' performance folders, which include semiannual faculty and peer evaluations.

A response of 1 indicated minimal or no desire to “reselect” a resident, a response of 4 indicated a strong interest in readmitting a resident, and the intermediate levels encompassed scores of 2 (some interest) and 3 (much interest). Residents who did not complete the 4-year training program because of premature elective or mandated termination were automatically assigned a numeric value of 1. A mean score was calculated for each resident. A resident with a score ≤1.5 was assigned to the lowest group; a score >1.5 and ≤2.5 to the second-lowest group; a score between 2.5 and 3.5 to the second-highest group; and a score ≥3.5 to the highest group. Once ranked, all resident identities were masked to preserve confidentiality.

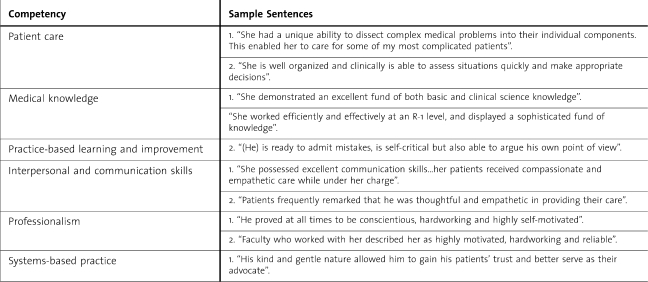

Deidentified applications of residents ranked in the highest and lowest groups were reviewed. LORs were independently abstracted by 2 experienced reviewers (N.A.H. and J.L.B.) and analyzed for themes based on the ACGME core competencies (patient care [PC], medical knowledge [MK], practice-based learning [PBL], interpersonal and communication skills [ICS], professionalism, and systems-based practice [SBP]) and 3 additional characteristics (research skills, leadership skills, and motivation) deemed important in defining a successful resident. table 1 illustrates examples of sentences in the LORs that pertain to each theme.

Table 1.

Sample Comments From Letters of Recommendation in Residency Applications for Each of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Core Competencies

The mean number of times each theme was mentioned was calculated for each applicant. Results were compared between residents in the highest group (very successful residents) and residents in the lowest group (unsuccessful residents). Data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test and the Student t test. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

During the 10-year study period, the program “matched” 7 to 8 residents per academic year. Seven residents left the program electively (to pursue residencies in other specialties) or upon request (because of poor clinical performance). These residents were automatically ranked in the lowest group. The residents who filled these vacated positions were excluded from analysis because they did not enter the residency program through the match. A total of 75 residents met inclusion criteria. Application data were available for all study participants.

There was substantial agreement between the 2 evaluators regarding resident performance. Approximately 50% of the residents in the groups analyzed received the same score from both evaluators. The remainder of the residents were assigned scores that differed by a value of 1 (eg, one score of 3 and one score of 4, providing a mean of 3.5).

Fourteen residents were ranked into the highest group and 15 into the lowest group. Sixty-five percent of the residents were women. Three international medical graduates were included in our analysis, with no difference between the highest and lowest groups.

A total of 110 LORs (median of 4 per resident) were reviewed. All letters referenced at least one of the core competencies. There was no temporal difference in the number of references in LORs between the beginning and the end of the study time period. The competencies of ICS and MK were most commonly noted, followed by PBL and professionalism, PC, and SBP. Of the 3 noncompetencies analyzed, motivation was most commonly cited. None of the letters recommended against accepting the applicant or contained overtly negative information.

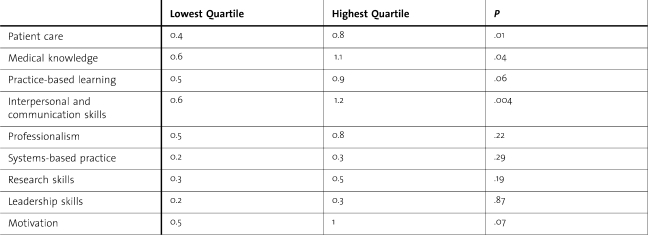

Of 9 themes evaluated, differences in 3 themes (PC, MK, and ICS) were statistically significant between residents in the highest versus the lowest groups (table 2). For each of these themes, the residents in the highest group had almost double the number of references to the respective ACGME competency than did their counterparts in the lowest group.

Table 2.

Mean Number of References in the Letters of Recommendation for Each Theme Evaluated

Discussion

The goal of a residency training program is to produce successful residents and outstanding clinicians. Unfortunately, the process of resident selection is inexact because of the limitations of quantifiable metrics in predicting resident success.2,3,12,13 Our study demonstrates that LORs written for medical students applying to residency programs in obstetrics and gynecology may be useful in predicting resident performance at the extremes.

To our knowledge, only one published study has demonstrated that the core competencies are referenced in LORs written for applicants to residency programs in obstetrics and gynecology, finding that 93% of 70 LORs contained at least one reference to one of the competencies, and 50% referenced 3 or more.14 This study did not analyze the predictive ability of LORs in the resident selection process.

References to 3 competencies (PC, MK, and ICS) were found to be significantly different between the groups in our study. There were almost twice as many references to these 3 competencies in LORs for residents in the highest group than in LORs for residents in the lowest group. These results are consistent with the ideal goal of a residency training program, namely, the production of a competent (aka “successful”) clinician. Similar results were noted by Greenburg et al15 in an analysis of LORs for a surgical residency program. Although specific references to the core competencies were not investigated, Greenburg and colleagues note that references to “fund of knowledge” and “work habits” correlated with a high score for the LOR.

The 3 competencies that did not achieve statistical significance were SBP, PBL, and professionalism. Until recently, the former 2 have not been a common part of the lexicon that defines medical student education. This may explain why writers of LORs for medical students infrequently address these skills. For example, the competency of SBP was referenced in letters for only 15 residents compared with MK, which was mentioned in letters for every resident.

There is no uniformly accepted means of measuring a resident's overall performance or “success.” In our study, we defined “success” based on the independent rankings of 2 experienced and respected resident educators. There are myriad ways of defining success, such as fellowship matching, continuation in academic medicine, and passage of licensing boards. We preferred our definition because it allowed us to best investigate whether we can reliably identify which applicants will become residency graduates from whom we receive the greatest return on our educational investment.

The primary limitations of our study include the relatively small cohort and the fact that our study was conducted at a single university-based program. It is possible that our outcomes are not generalizable to residents in other programs. We do not believe that including residents who were prematurely terminated from our program is a study limitation. Although these residents may be considered a separate cohort, we believe that they make up an important element of a “success failure.” Residents who do not complete their training program lose personal time and introduce uncertainty and anxiety within the educational program.

With increasing emphasis on competency-based learning in medical education, it seems prudent to move toward competency-based assessments and recommendations. Not all program directors are interested in going the way of emergency medicine and adopting a formal, standardized LOR.16 We suggest that incorporating the competencies more consistently into LORs would allow for a common language and structure without mandating a complete reformation of current conventions.

Footnotes

Hindi E. Stohl, MD, is a second year fellow in Maternal Fetal Medicine from the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine; Nancy A. Hueppchen, MD, MSc, is Assistant Professor of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and Assistant Dean for Curriculum, Johns Hopkins University; and Jessica L. Bienstock, MD, MPH, is Professor of Maternal Fetal Medicine and Residency Program Director for the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Results of this study were presented at the 2009 Annual Meeting of the Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (CREOG & APGO), March 12, 2009, in San Diego, CA.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Olawaiye A, Yeh J, Withiam-Leitch M. Resident selection process and prediction of clinical performance in an obstetrics and gynecology program. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(4):310–315. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1804_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borowitz SM, Saulsbury FT, Wilson WG. Information collected during the residency match process does not predict clinical performance. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(3):256–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell JG, Kanellitsas I, Shaffer L. Selection of obstetrics and gynecology residents on the basis of medical school performance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):1091–1094. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly KA, Levine SC, Adams GL. Predictors for resident success in otolaryngology. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202(4):649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor RA, Reisch JS, Valentine RJ. Factors related to attrition in surgery residency based on application data. Arch Surg. 2008;143(7):647, 651; discussion 651–652. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.7.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stohl HE, Hueppchen NA, Bienstock JL. Can medical school performance predict residency performance?: resident selection and predictors of successful performance in obstetrics and gynecology. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):322–326. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00101.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeZee KJ, Thomas MR, Mintz M, Durning SJ. Letters of recommendation: rating, writing, and reading by clerkship directors of internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):153–158. doi: 10.1080/10401330902791347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLisa JA, Jain SS, Campagnolo DI. Factors used by physical medicine and rehabilitation residency training directors to select their residents. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73(3):152–156. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagoner NE, Suriano JR, Stoner JA. Factors used by program directors to select residents. J Med Educ. 1986;61(1):10–21. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisdorff EJ, Hayes OW, Carlson DJ, Walker GL. Assessing the new general competencies for resident education: a model from an emergency medicine program. Acad Med. 2001;76(7):753–757. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200107000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. http://www.lcme.org/functions2010jun.pdf. Updated May 2011. Accessed August 2, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dirschl DR, Dahners LE, Adams GL, Crouch JH, Wilson FC. Correlating selection criteria with subsequent performance as residents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;(399):265–271. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200206000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thordarson DB, Ebramzadeh E, Sangiorgio SN, Schnall SB, Patzakis MJ. Resident selection: how we are doing and why. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:255–259. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31805d7eda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blechman A, Gussman D. Letters of recommendation: an analysis for evidence of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. J Reprod Med. 2008;53(10):793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenburg AG, Doyle J, McClure DK. Letters of recommendation for surgical residencies: what they say and what they mean. J Surg Res. 1994;56(2):192–198. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1994.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keim SM, Rein JA, Chisholm C, Dyne PL, Hendey GW, Jouriles NJ, et al. A standardized letter of recommendation for residency application. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(11):1141–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]