Abstract

Introduction

The increased demand for clinician-educators in academic medicine necessitates additional training in educational skills to prepare potential candidates for these positions. Although many teaching skills training programs for residents exist, there is a lack of reports in the literature evaluating similar programs during fellowship training.

Aim

To describe the implementation and evaluation of a unique program aimed at enhancing educational knowledge and teaching skills for subspecialty medicine fellows and chief residents.

Setting

Fellows as Clinician-Educators (FACE) program is a 1-year program open to fellows (and chief residents) in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Iowa.

Program Description

The course involves interactive monthly meetings held throughout the academic year and has provided training to 48 participants across 11 different subspecialty fellowships between 2004 and 2009.

Program Evaluation

FACE participants completed a 3-station Objective Structured Teaching Examination using standardized learners, which assessed participants' skills in giving feedback, outpatient precepting, and giving a mini-lecture. Based on reviews of station performance by 2 independent raters, fellows demonstrated statistically significant improvement on overall scores for 2 of the 3 cases. Participants self-assessed their knowledge and teaching skills prior to starting and after completing the program. Analyses of participants' retrospective preassessments and postassessments showed improved perceptions of competence after training.

Conclusion

The FACE program is a well-received intervention that objectively demonstrates improvement in participants' teaching skills. It offers a model approach to meeting important training skills needs of subspecialty medicine fellows and chief residents in a resource-effective manner.

Background

In the 1990s, it became clear that the traditional “triple threat” expectation for faculty to conduct research, teach learners, and care for patients had become much more difficult to meet. In response to this difficulty, many academic centers developed a clinical track for faculty who were excellent clinicians and who could teach younger colleagues about patient care.1 Such individuals have a set of tangible skills that can be learned, measured, and improved upon. Many institutional or departmental programs focus on helping faculty enhance their educational knowledge and teaching skills.2 Starting programs earlier in clinician-educators' careers may have a greater impact on future learners, as well as the clinician-educators' own career choices and job satisfaction.

The next generation of clinician-educators likely will include graduates of subspecialty fellowship training programs. Surveys of fellowship graduates identify the need and desire for teaching skills training as an important component of career development,3,4 yet there are few reports of teaching skills training programs during fellowship.

Faculty in the General Internal Medicine division at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine recognized the need for fellows to receive training in teaching skills to prepare them for positions as clinician-educators. In response, the Fellows as Clinician-Educators (FACE) program was established in 2001 for general internal medicine fellows. At the time the program was established, the General Internal Medicine division had 1 to 2 fellows each year. Fellows were required to participate in the FACE program as part of their fellowship training.

While the program was well received, its organizers noted that implementing a program for such a limited number of fellows per year was not cost or resource effective. We sent an informal survey to directors of all internal medicine subspecialty fellowships at the institution to determine their interest in the availability of teaching skills training for their fellows. In 2003, the FACE program was expanded to include fellows in any of the 11 medicine subspecialty programs and chief residents interested in a clinician-educator career, providing economy of scale and creating a teaching community for fellows.

The aim of the FACE program is to enhance internal medicine fellows' educational knowledge and teaching skills in order to prepare them for careers in academic medicine. We expected that the program would lead to increased confidence and improved teaching skills.

Methods

Program Description

The 1-year FACE program is open to fellows and chief residents in the Department of Internal Medicine. The program can accommodate up to 12 participants annually. Participation is required for chief residents and is voluntary for fellows. Fellowship directors are asked to provide protected time in which fellows can participate in course activities. Fellows are encouraged to participate during their second year or third fellowship year (due to substantial clinical responsibilities during the first year of fellowship training). We limit the number of participants to 12 because that is the number we feel (with our present resources) we can teach effectively. This represents 25% of the eligible fellows (ie, second-year or third-year fellows who have not yet taken the course). Educational and administrative support for the FACE program is provided by an associate program director of the core residency and by an education specialist from the Office of Consultation and Research in Medical Education. Salary support for the associate program director is provided as stipulated in the Residency Review Committee program requirements, and the departmental educational budget provides salary support for the education specialist.

The FACE program involves 2-hour monthly meetings, running from September to June of each academic year. Each session consists of a brief presentation, reflection or self-assessment exercises, and skill practice activities. Sessions are interactive and include group discussions, paired activities, presentations and critiques, or demonstrations. Some sessions require participants to complete homework either before or after the session. Several sessions include a guest facilitator. table 1 provides a description of the 10 annual sessions, including session objectives and activities.

Table 1.

FACE Monthly Sessions

Fellows are also encouraged to participate in at least 1 of 3 supplemental practical teaching opportunities that reinforce specific FACE session topics, such as (1) serving as a clinician mentor supervising 4 medical or physician assistant students as they learn to obtain histories and perform physical examinations; (2) participating in division-specific teaching directed by participants' respective fellowship directors; and (3) participating in an educational research or curriculum development project. Between 2004 and 2009, nearly half of the 48 FACE fellows participated as clinician mentors for second-year medical students. An example of a division-specific teaching project was demonstration of physical examination skills in rheumatology; and an example of a research project was development of a curriculum to teach ultrasonography to residents, using a heart sound simulator and case-based learning for medical students.

Program Evaluation

Our evaluation assesses changes in participants' actual teaching behaviors based on their performance results of the Objective Structured Teaching Examinations (OSTE).5 In addition, we examine participants' own perceptions of their teaching skills and knowledge and the impact of the program on these skills and participants' confidence in implementing them, as recommended by Mann and colleagues in a recent review regarding reflection in medical education.6

The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board, no. 200902762.

Objective Structured Teaching Examination

The OSTE is an observational examination with standardized students that has been used for more than a decade to evaluate the clinical teaching skills of medical faculty and residents and is an established method for assessing the effectiveness of teaching skills programs.5,7–11,13,14

FACE participants complete an OSTE at the start and the conclusion of the FACE program. We developed a 3-station OSTE adapted from those used by Morrison et al,12 with each station featuring standardized students who enacted different teaching scenarios. We trained junior or senior medical students to enact specific teaching scenarios and coached them in how to give effective written feedback. We limited the OSTE to 3 stations due to time and financial constraints and focused stations on teaching situations fellows were most likely to encounter. These scenarios included giving feedback on a history and physical examination, precepting in an ambulatory setting, and giving a mini-lecture. The fellows were given 15 minutes for each station, and sessions were recorded. The standardized students provided open-ended feedback comments, given to fellows along with a copy of the recorded session. Each scenario was also discussed during FACE teaching sessions.

To assess the FACE program, the recordings were evaluated by 2 independent raters who were not informed whether the OSTE was performed prior to or after participation in the FACE program. Prior to rating the OSTE, the raters underwent training to ensure interrater reliability. The 2 raters and 3 course facilitators evaluated several recordings and compared notes until all were using similar evaluation techniques. Rating scores were not shared with FACE participants.

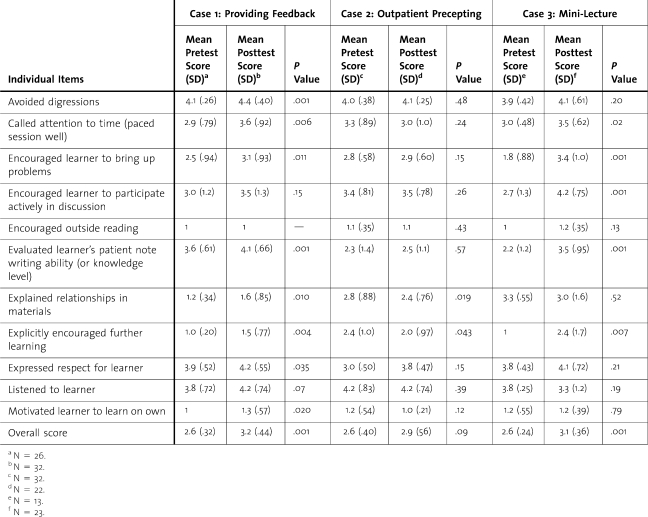

We used the modified version of the Stanford Faculty Development 26 (SFDP-26) form, developed and validated by Morrison et al,12 to evaluate the OSTE. On all items, higher scores consistently indicated better teaching skills. For the purpose of this study, we report the 11 items common to all 3 cases (table 2).

Table 2.

Pretest to Posttest Differences for Individual Items and Overall Scores

In order to maximize the sample size for comparisons, we used t-tests of unmatched samples to compare the significance of the differences in means for the individual variables. In addition, we created overall scores for each case by taking the mean of all of the variables for a particular case.

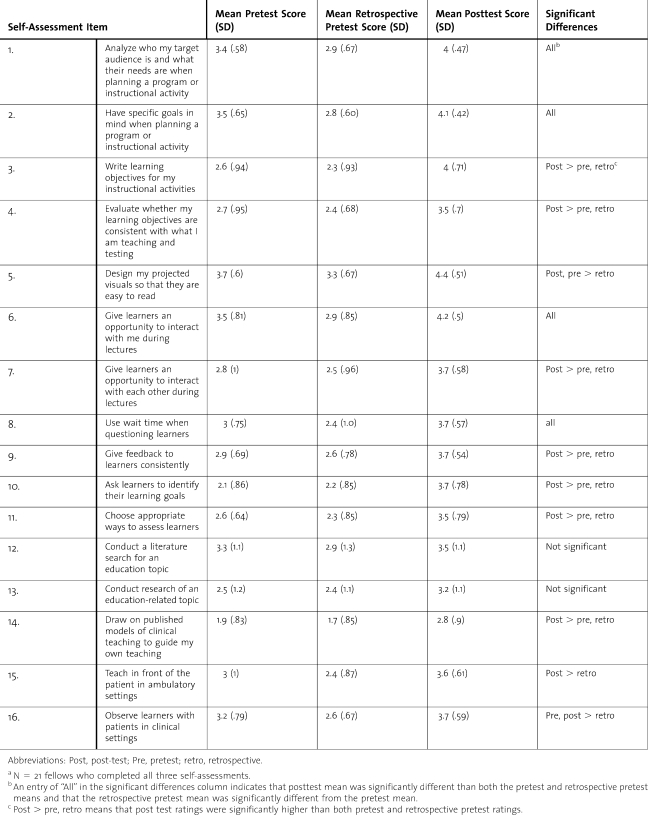

Self-Assessments

Retrospective precompetence and postcompetence assessments using a 16-item standardized questionnaire were used by fellows to rate their pretraining competence in educational skills at the beginning of the program and, retrospectively, their pretraining competence at the end of training. The fellows also rated their post-training competence at the end of training. Questionnaire items addressed specific educational skills and strategies such as using goals and objectives, promoting interaction, and giving feedback. Items asked fellows to rate their competence on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I do not do this”) to 5 (“I am highly competent in doing this”). Items were developed based on reviews of literature from similar programs and program-specific objectives.2,5

To assess differences among self-assessed skills on the pretest, retrospective pretest, and posttest, we used analysis of variance with time as the category. A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant.

Participants' Evaluations of the Program

At the end of the training year, participants were asked to identify the strengths of the program, areas for improvement, and topics they would have liked to see addressed in the program. They also evaluated the contribution of each of the program facilitators.

Results

From 2004 to 2009, 29 fellows and 15 chief residents participated in the program. Fellow participants represented 11 different subspecialty fellowship training programs. OSTE and Self-Assessment results comprise data from the fellows only.

Objective-Structured Teaching Examination

Performance on Case 1 of the OSTE (providing feedback) showed statistically significant improvement for 8 of 11 of the variables (table 2). Performance on Case 2 of the OSTE (outpatient precepting) showed statistically significant improvement for 2 of 11 variables, while performance on Case 3 (mini-lecture) showed statistically significant improvement for 5 of 11 variables. The overall scores for Cases 1 and 3 showed statistically significant improvement, while the overall score for Case 2 did not.

Self-Assessments

Retrospective Pre-Competence and Post-Competence Assessments

Self-assessments of fellows' teaching skills improved as a result of the training program when measured prospectively and retrospectively. Comparison of preratings and postratings of competence revealed significant differences among all items except for items dealing with literature searches and educational research; significant findings are shown in table 3. Fellows tended to rate their pretraining competence higher prior to training than they did retrospectively, showing increased awareness of concepts as a result of participation in the program.

Table 3.

Pretest to Posttest Differences in Self-Assessment for FACE Participantsa

Participant Evaluation of the Program

While some fellows' comments about the strengths of the program focused on specific skills and session topics, the majority of comments were global statements identifying the focus on a variety of key teaching topics, the open discussion format, and opportunities to receive feedback on their own teaching. Several fellows particularly appreciated the opportunity to devote time to reflect on their own teaching and general teaching issues.

Career Impact

To date, there have been 48 participants in the FACE program. Of those who have completed fellowship training, 27 participants moved to academic medical settings and are in roles that require them to function as clinical teachers. Eight participants are still in training and are developing career plans. The remaining participants moved into community-based, university-affiliated clinical positions.

Discussion

The aim of the FACE program was to provide centralized training to allow fellows to develop and enhance their knowledge, skills, and confidence as clinician-educators. Residents-as-teachers programs exist throughout the country and include a comprehensive program in our own institution.16 A recent literature review identified key components in the development and assessment of such programs.5 At the same time, few examples exist of programs that target subspecialty fellows, even though training as a clinician-educator involves skills and approaches that are different from training as a physician-scientist.1

The FACE program is an example of a centralized labor-efficient program developed to address concerns that are shared by most academic medicine departments.

Several challenges exist in providing teaching skills training to fellows. Unlike residency programs, most medical fellowship programs have only a limited number of participants each year, and providing formal teaching skills training in each fellowship program becomes cost prohibitive. Another challenge is the lack of faculty and staff with the expertise to provide this training. In contrast to residents, who are often actively involved in clinical teaching and have the opportunity to improve their teaching skills, fellows have less exposure and opportunity to supervise learners. Finally, because of the low numbers, participants often do not have the opportunity for interaction with peers about educational issues, which has been identified as a key component of learning and critical examination of teaching skills and educational challenges.2 We designed the FACE program to address these challenges.

The FACE program was started to prepare internal medicine fellows for their potential future roles as clinician-educators. The model described by Kirkpatrick17 for evaluating educational outcomes has been used extensively for categorizing the focus and rigor of educational interventions and uses 4 levels of assessment, as follows: (Level 1) satisfaction, reaction, and preference; (Level 2) skills, attitudes, and knowledge; (Level 3) behavior; and (Level 4) long-term outcomes. In terms of satisfaction, fellows value the program and its teaching. The self-assessed teaching skills at the end of the program were significantly improved compared with the same self-assessments at the beginning of the program. Fellows rated their pretraining and retrospective pretraining skills significantly lower than their post-training ratings of their skills.18,19 At the second level, impact on skills was demonstrated through improved performance of the OSTE at the conclusion of the program. Using a 3-station OSTE, we learned useful information about teaching skills while conserving the resources that a longer OSTE would require. The OSTE was also an important formative tool in that it forced the fellows to think about how they paced themselves when teaching and how to prioritize what they teach.

In the future, it will be important to show the FACE program has a sustained impact on actual teaching situations (Level 3) and on long-term career outcomes of the FACE participants, such as participation in educational activities, benefit to the learners they teach, and ultimately, to patient care outcomes (Level 4).

There are several limitations to our study. It was done with a relatively small sample at one medical center. Some areas measured by the OSTE did not show significant improvement. This may be because of a high level of performance at baseline, leaving little room for measurable improvement, because areas assessed by the OSTE were not taught through the FACE program. In addition, some improvements due to the FACE program may not have been measured given the time and other limitations of the OSTE. To facilitate comparison across the 3 cases, we selected 11 items relevant for all cases from the items in the SFDP-26 form. This may have introduced bias, but we believed having cross-case comparisons outweighed this potential risk. Finally, although participation in the FACE program requires the support of the fellows' training director and requires a commitment to full participation, patient care responsibilities may have limited full participation. We acknowledge that a more rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of the program would require pretest and post-test data from a control group of fellows who did not participate in the program. Unfortunately, resources did not allow for this type of control group evaluation design.

Conclusion

We describe an educational curriculum targeted toward subspecialty fellows in internal medicine, which provides an interdisciplinary forum to teach educational strategies to individuals considering careers as clinician-educators. The program offers efficiencies of scale not available at the individual fellowship program level. It improved the teaching skills of subspecialty fellows. For individuals planning to work in an academic setting, we believe the FACE program can help prepare them for a role as a clinician-educator.

Footnotes

MARCY E. ROSENBAUM, PHD, is Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, and Faculty Development Consultant for the Office of Consultation and Research in Medical Education, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; JANE A. ROWAT, MS, is Director for Educational Development, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; KRISTI J. FERGUSON, PHD, is Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; ERIN SPENGLER, MD, is a third-year Resident, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine; POONAM SOMAI, MD, is a rheumatologist, Graves Gilbert Clinic, Bowling Green, Kentucky; JAMES L. CARROLL, MD, is Associate Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School; and SCOTT A. VOGELGESANG, MD, is Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine.

The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Bunton SA, Mallon WT. The continued evolution of faculty appointment and tenure policies at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):281–289. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180307e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinert Y, Mann K, Centeno A, et al. A systematic review of faculty development initiatives designed to improve teaching effectiveness in medical education: BEME Guide No. 8. Med Teach. 2006;28(6):497–526. doi: 10.1080/01421590600902976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlander JD, Callahan CM. Fellowship training in academic general internal medicine: A curriculum survey. J Gen Int Med. 1991;6:461–465. doi: 10.1007/BF02598172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempainen RR, Hallstrand TS, Culver BH, Tonelli MR. Fellows as teachers: The teacher-assistant experience during pulmonary subspecialty training. Chest. 2005;128(1):401–406. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post RE, Quattlebaum RG, Benich JJ., III Residents-as-teachers curricula: A critical review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):373–480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971ffe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595–621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson DE, Lawrence SL, Krogull SR. Using standardized ambulatory teaching situations for faculty development. Teach Learn Med. 1992;4(1):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesky LG, Wilkerson LA. Using standardized students to teach a learner-centered approach to ambulatory precepting. Acad Med. 1994;69(12):955–957. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prislin MD, Fitzpatrick C, Giglio M, Lie D, Radecki S. Initial experience with a multi-station objective structured teaching skills evaluation. Acad Med. 1998;73(10):1116–1118. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelula MH. Using standardized medical students to improve junior faculty teaching. Acad Med. 1998;73(5):611–612. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schol S. A multiple station test of the teaching skills of general practice preceptors in Flanders, Belgium. Acad Med. 2001;76(2):176–180. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200102000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrison EH, Boker JR, Hollingshead J, Prislin MD, Hitchcock MA, Litzelman DK. Reliability and validity of an objective structured teaching examination for generalist resident teachers. Acad Med. 2002;77((suppl)):S29–S32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunnington GL, DaRosa D. A prospective randomized trial of a residents-as-teachers training program. Acad Med. 1998;73(6):696–700. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199806000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison EH, Rucker L, Boker JR, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a longitudinal residents-as-teachers curriculum. Acad Med. 2003;78(7):722–729. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992;5(4):419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell S, Cook J, Densen P. A teaching rotation for residents. Acad Med. 1994;69(5):434–437. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating Training: The Four Levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLeod PJ, Steinert Y, Snell L. Use of retrospective pre/post assessments in faculty development. Med Educ. 2008;42(5):543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pratt CC, Mcguigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: Using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Evaluation. 2000;21(3):341–349. [Google Scholar]