Abstract

Background

Frequent missed patient appointments in resident continuity clinic is a well-documented problem, but whether rates of missed appointments are disproportionate to standard academic practice, what patient factors contribute to these differences, and health care outcomes of patients who frequently miss appointments are unclear.

Methods

The overall population for the study was composed of patients in an academic internal medicine continuity clinic with 5 or more office visits between January 2006 and December 2008. We randomly selected 325 patients seen by resident physicians and 325 patients cared for by faculty. Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the relationship between patient factors and missed appointments. Health outcomes were compared between patients with frequent missed appointments and the remainder of the study sample, using Cox regression analysis.

Results

Resident patients demonstrated significantly higher rates of missed appointments than faculty patients, but this difference was explained by patient factors. Factors associated with more missed appointments included use of a medical interpreter, Medicaid insurance, more frequent emergency department visits, less time impanelled in the practice, and lower proportion of office visits with the primary care provider. Patients with frequent missed appointments were less likely to be up to date with preventive health services and more likely to have poorly controlled blood pressure and diabetes.

Conclusions

We found that the disproportionate frequency of missed appointments in resident continuity clinic is explained by patient factors and practice discontinuity, and that patients with frequent missed appointments demonstrated worse health care outcomes.

Introduction

Continuity clinic is a mandatory component of resident education to allow residents to learn outpatient disease management in the context of prevention and health promotion, while providing them opportunity to build longitudinal relationships with their patients.1 Missed patient appointments in continuity clinic is a well-documented problem, resulting in discontinuity, disrupted schedules, and lost learning opportunities for residents to see the outcome of their treatment plans.2–7 Whether rates of missed appointments are disproportionate to standard academic practice, and what patient factors (if any) contribute to these differences is not clear.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients who frequently miss appointments tend to be younger, of lower socioeconomic status, have a history of missed appointments, and have government-provided insurance.8–11 Yet little is known about the health care outcomes of patients who frequently miss appointments. We compared missed appointment rates in resident and faculty primary care practices, evaluated patient characteristics associated with missed appointments, and ascertained health care outcomes of patients with frequent missed appointments. These results will be used to inform quality improvement initiatives aimed at reducing rates of missed appointments in continuity clinic.

Methods

Setting and Study Sample

This study was conducted in the primary care internal medicine (PCIM) clinics at Mayo Clinic Rochester, an academic practice where patients are assigned to either a faculty member or resident as their primary care provider. PCIM includes 38 faculty physicians and 96 internal medicine residents, divided equally across all 3 years of training, who collectively care for more than 39 000 patients. Faculty physicians spend most of their time seeing their own impanelled patients, and most supervise resident continuity clinic one half-day per week. During the study interval, each resident saw patients in clinic one half-day per week for 10 months of the year plus burst continuity experiences for 1 month during his or her first and third years. Residents have a 93% fill rate and see an average of 157 patients in an academic year (3.6 visits per half-day).

After approval by the Institutional Review Board, all PCIM patients who had 5 or more office visits between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2008, were identified, and subsets of 325 patients impanelled to resident providers and 325 patients impanelled to faculty providers were randomly selected for evaluation. A missed appointment was defined as a scheduled PCIM visit that was neither attended by the patient nor previously canceled. The number of missed appointments, demographic information, patient characteristics, and practice characteristics of this sample were retrieved by manual chart review.

Health Outcome Measurements

Three health outcome domains were evaluated in the study sample: completion of age-appropriate preventive health services, glycemic control among patients with diabetes, and blood pressure control. Age-appropriate preventative services as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force12 were extracted by chart review. Patients who lacked at least 2 of these preventive services as of December 30, 2008, were defined as not being up to date. At the time of the study, the American Diabetes Association recommended glycemic control to target hemoglobin A1c (HgbA1c) <7%.13 We defined poor diabetic control as having at least 2 HgbA1c >7% during the time period 2006–2008. Poorly controlled blood pressure was defined as having at least 2 separate systolic pressures ≥160 and/or diastolic pressures ≥100 (stage 2 hypertension).14

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between faculty and resident patients using the Student t test. Linear multiple regression analysis was performed to compare the rate of missed appointments between the faculty and resident patients, controlling patient characteristics. Patients who missed appointments ≥20% of the time or had ≥5 missed appointments during the study interval were characterized as a “frequent missed appointments” group. Health outcomes were compared between the frequent missed appointments group and the remainder of the study sample using Cox regression analysis.

Results

Comparison of Missed Appointments Between Resident and Faculty Patients

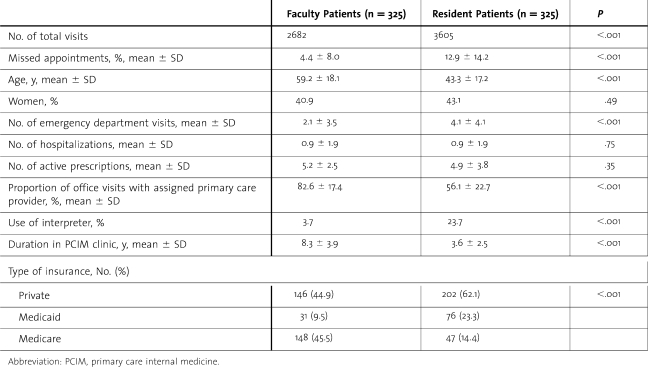

Resident patients demonstrated significantly higher rates of missed appointments than faculty patients (table 1). Resident patients were younger than faculty patients, more likely to have Medicaid insurance, and more likely to require a medical interpreter. Resident patients' office visits were less likely to be with their primary care provider than faculty patients' visits, and resident patients were more likely to have a shorter affiliation with the PCIM clinic. Resident patients had more emergency department visits during the study interval, but the number of hospitalizations and number of active prescriptions were statistically similar between the 2 groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Missed Appointments and Demographic Factors Between Resident and Faculty Patients in an Academic Internal Medicine Practice, 2006–2008

Associations Between Patient Characteristics and Missed Appointments

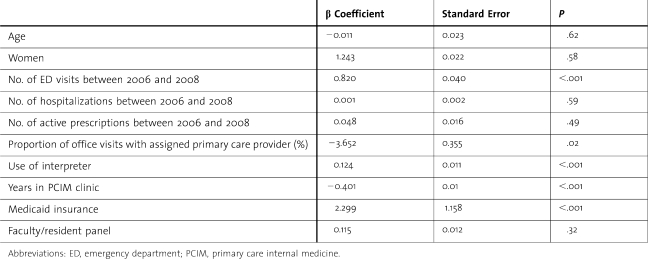

Patient factors associated with higher frequency of missed appointments included use of a medical interpreter, Medicaid insurance, and more frequent emergency department visits (table 2). Patient factors associated with lower frequency of missed appointments included longer affiliation with the PCIM clinic and higher proportion of office visits with the primary care provider (table 2). After adjustment for the above, there was no difference in rates of missed appointments between the resident and faculty practices (table 3).

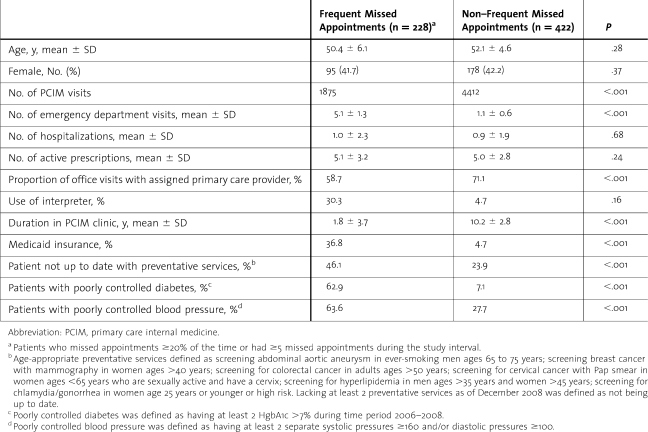

Table 2.

Comparison of Demographics, Practice Characteristics, and Health Care Outcomes Between Patients With Frequent Missed Appointments and the Remainder of the Study Sample

Table 3.

Multiple Linear Regression Model Predicting Frequency of Missed Appointments (N = 650; Adjusted R2 = 0.64)

Associations Between Missed Appointments and Health Outcomes

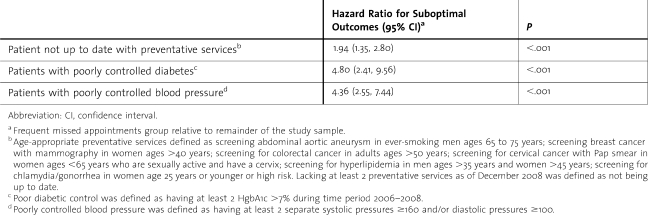

Of the 650 patients in the study, 228 (35%) were identified as those with frequent missed appointments (missed appointments ≥20% of the time or ≥5 missed appointments during the study interval; table 2). These patients were less likely to be up to date with age-appropriate preventive health services. Among the 166 patients with a diagnosis of diabetes, patients with frequent missed appointments were more likely to have HgbA1c >7. Finally, among 279 patients with a diagnosis of hypertension, patients with frequent missed appointments were more likely to have poor blood pressure control (table 4).

Table 4.

Health Care Outcomes of Patients With Frequent Missed Appointments

Discussion

Despite sharing similar clinical practice parameters and allied health staff, the resident practice had a much higher rate of missed appointments compared with the faculty practice. The high rate of missed appointments in resident continuity clinic is consistent with previous reports, but the comparison with a faculty practice adds to the literature by demonstrating that the difference in missed appointments between the 2 practices is explained by patient factors. Differences in patient characteristics between resident and faculty practices are well documented nationally, such that socioeconomic position of resident patients tends to be lower than for faculty practice patients.15–17 The reasons for these discrepancies are not clear, but may include the notion that faculty practices are more likely to be at capacity, thereby shifting new and less socioeconomically stable patients to resident panels. Further, patients with higher socioeconomic position may be more likely to request a faculty provider.

It is essential that clinic support for these patients and their resident providers are optimized. First, support for comprehensive outpatient care (eg, allied health staff services) should be equally robust between the resident and faculty practices.18 Second, resident continuity clinic redesign should maximize access to and utilization of evidence-based multidisciplinary models of care for their patients (eg, medical home).19 Finally, resident education and mentorship regarding the care of vulnerable populations should permeate the continuity clinic experience,20,21 particularly in the context of low knowledge among residents about factors affecting underserved patients22 and waning attitudes toward these populations as training proceeds.23

Consistent with prior reports,7–10 our study demonstrated that patients who required an interpreter and have government-provided health insurance missed more appointments to continuity clinic. Our study adds to this literature by demonstrating that patients with frequent missed appointments are less likely to have a long-term relationship with their primary care practice, have a lower proportion of visits with their own physician, and are more likely to visit the emergency department. Barriers to completing medical appointments among these patient populations have been inadequately explored in the literature. Qualitative studies among patients who frequently miss appointments have identified transportation, wait times, not knowing the reason for the appointment, competing priorities, inefficiencies with the booking system, and perceived disrespect as barriers to keeping appointments.9,10

Interventions with success at reducing rates of missed appointments include reminders through mail and phone,24,25 text message reminders,26 and orientation to the clinic.27 Testing of interventions aimed specifically at improving rates of missed appointments in resident continuity clinic is needed. In addition to reminder mechanisms, our findings suggest that recent trends toward redesign of resident continuity clinic practices aimed at enhancing provider or team continuity with patients may reduce rates of missed appointments.28

We found that patients with frequent missed appointments were less likely to have received preventive health services and more likely to have poorly controlled hypertension and diabetes. Two earlier studies also correlated missed appointments with worse glycemic control and medication adherence among patients with diabetes.29,30 Although these associations are not likely to be causal, a high rate of missed appointments may serve as a useful barometer of barriers to self-care. This easily measured variable may help identify patients most likely to benefit from case management. Prior attempts to identify patients for case management have focused on surrogates for medical complexity (eg, age, number of active medications, number of diagnoses, etc).31,32 This may leave out socioeconomically disadvantaged patients with chronic illness who may benefit from case management to remove barriers to keeping appointments and adhering to treatment plans.

Limitations of our study include its retrospective, observational nature, and the availability of particular variables for analysis. Causality among variables cannot be implied. Our single-center findings may not be generalized to other academic practices. Although differences in resident and faculty practice demographics are consistent with other reports, the rate of missed appointments in our sample is lower than in previous studies.

Conclusion

We found that the disproportionate frequency of missed appointments in resident continuity clinic is explained by patient factors and practice continuity, and that a high rate of missed appointments predicts worse health care outcomes. These findings emphasize the importance of further exploratory studies aimed at identifying barriers to attending appointments and testing of interventions at the level of residents, patients, and continuity clinic systems to further address these behaviors.

Footnotes

All authors are in the Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine. Douglas L. Nguyen, MD, is Instructor in Medicine; Ramona S. DeJesus, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine; and Mark L. Wieland, MD, MPH, is Assistant Professor of Medicine.

The authors would like to thank primary care internal medicine (PCIM) office staff Susan Claxton and Cami McElmury for their assistance in the data collection process. This work was at presented at the 2010 National American College of Physicians Meeting in Toronto, Canada.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Residency Education in Internal Medicine. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/140_internal_medicine_07012007.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hixon Al, Chapman RW, Nuovo J. Failure to keep clinic appointments: implications for residency education and productivity. Fam Med. 1999;31(9):627–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson BJ, James MW, Pontious MJ. Reduction and management of no-shows by family medicine residency practice exemplars. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(6):534–538. doi: 10.1370/afm.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weingarten N, Meyer DL, Schneid JA. Failed appointments in residency practices: who misses them and what providers are affected. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10(6):407–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christakis DA, Feudtner C, Pihoker C, Connell FA. Continuity of care for children with diabetes who are covered by Medicaid. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;2(2):99–103. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0099:caqocf>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hixon AL, Chapman RW, Nuovo J. Failure to keep clinic appointments: implications for residency education and productivity. Fam Med. 1999;31(9):627–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tesch B, Lee H, McDonald M. Reducing the rate of missed appointments among patients new to a primary care clinic. J Ambul Care Manage. 1984;7(3):32–41. doi: 10.1097/00004479-198408000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barron WM. Failed appointments: who misses them, why they are missed, and what can be done. Prim Care. 1980;7(4):563–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith CM, Yawn BP. Factors associated with appointment keeping in a family practice residency clinic. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(1):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B. Why we don't come: patient perceptions on no-shows. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):541–545. doi: 10.1370/afm.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankel S, Farrow A, West R. Non-attendance or non-invitation?: a case-control study of failed appointments. BMJ. 1989;298(6684):1343–1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6684.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. http://www.preventiveservices.ahrq.gov/#uspstf. Accessed June 28, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(suppl 1):S12–S54. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL., Jr The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook RH, Fink A, Kosecoff J, Linn LS, Watson WE, Davies AR, et al. Educating physicians and treating patients in the ambulatory setting: where are we going and how will we know when we arrive. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(3):392–398. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yancy WS, MacPherson DS, Hanusa BH. Patient satisfaction in resident and attending ambulatory care clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.91005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serwint JR, Thoma KA, Dabrow DM, Hunt LE, Barratt MS, Shope TR, et al. Comparing patients seen in pediatric resident continuity clinics and national ambulatory medical care survey practices: a study from the continuity research network. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e849–e858. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keirns CC, Bosk CL. Perspective: the unintended consequences of training residents in dysfunctional outpatient settings. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):498–502. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816be3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers FJ, Weinberger SE, Fitzgibbons JP, Glassroth J, Duffy FD, Clayton CP, et al. Redesigning residency training in internal medicine: the consensus report of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Education Redesign Task Force. Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1211–1219. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159d010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zweifler J, Gonzalez AM. Teaching residents to care for culturally diverse populations. Acad Med. 1998;73(10):1056–1061. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199810000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):654–665. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieland ML, Beckman TJ, Cha SS, Beebe TJ, McDonald FS Underserved Care Curriculum Collaborative. Resident physicians' knowledge of underserved patients: a multi-institutional survey. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):728–733. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crandall SJ, Volk RJ, Loemker V. Medical students' attitudes toward providing care for the underserved: are we training socially responsible physicians. JAMA. 1993;269(19):2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macharia WM, Leon G, Rowe BH. An overview of interventions to improve compliance with appointment keeping for medical services. JAMA. 1992;267(13):1813–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perron NJ, Dao MD, Kossovsky MP, Miserez V, Chuard C, Calmy A, et al. Reduction of missed appointments at an urban primary care clinic: a randomised controlled study. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liew SM, Tong SF, Lee VK, Ng CJ, Leong KC, Teng CL. Text messaging reminders to reduce non-attendance in chronic disease follow-up: a clinical trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59(569):916–920. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X472250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain S, Chou CL. Use of an orientation clinic to reduce failed new patient appointments in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(12):878–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzgibbons JP, Bordley DR, Berkowitz LR, Miller BW, Henderson MC. Redesigning residency education in medicine: a position paper from the Association of the Program Directors in Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):920–926. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1685–1687. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0747-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selby JV, Swain BE, Gerzoff RB, Karter AJ, Waitzfelder BE, Brown AF, et al. Understanding the gap between good processes of diabetes care and poor intermediate outcomes: Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Med Care. 2007;45(12):1144–1153. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181468e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oeseburg B, Wynia K, Middel B, Reijneveld SA. Effects of case management for frail older people or those with chronic illness: a systematic review. Nurs Res. 2009;58(3):201–210. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181a30941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd CM, Shadmi E, Conwell LJ, Griswold M, Leff B, Brager R, et al. A pilot test of the effect of guided care on the quality of primary care experiences for multimorbid older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):536–542. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]