Abstract

Background

While the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recommends multisource feedback (MSF) of resident performance, there is no uniformly accepted MSF tool for emergency medicine (EM) trainees, and the process of obtaining MSF in EM residencies is untested.

Objective

To determine the feasibility of an MSF program and evaluate the intraclass and interclass correlation of a previously reported resident professionalism evaluation, the Humanism Scale (HS).

Methods

To assess 10 third-year EM residents, we distributed an anonymous 9-item modified HS (EM-HS) to emergency department nursing staff, faculty physicians, and patients. The evaluators rated resident performance on a 1 to 9 scale (needs improvement to outstanding). Residents were asked to complete a self-evaluation of performance, using the same scale.

Analysis

Generalizability coefficients (Eρ2) were used to assess the reliability within evaluator classes. The mean score for each of the 9 questions provided by each evaluator class was calculated for each resident. Correlation coefficients were used to evaluate correlation between rater classes for each question on the EM-HS. Eρ2 and correlation values greater than 0.70 were deemed acceptable.

Results

EM-HSs were obtained from 44 nurses and 12 faculty physicians. The residents had an average of 13 evaluations by emergency department patients. Reliability within faculty and nurses was acceptable, with Eρ2 of 0.79 and 0.83, respectively. Interclass reliability was good between faculty and nurses.

Conclusions

An MSF program for EM residents is feasible. Intraclass reliability was acceptable for faculty and nurses. However, reliable feedback from patients requires a larger number of patient evaluations.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the paper version of the Emergency Medicine Humanism Scale (426KB, pdf) .

Introduction

In 1997, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) embarked on a long-term initiative known as the Outcome Project.1 The purpose was to place increased emphasis on educational outcome assessment in the accreditation process. As part of this process, the ACGME identified a set of 6 competencies every resident should achieve before graduation.

In 2006, the ACGME required programs to assess residents in all competency domains, using at least 1 assessment tool in addition to standard global/end-of-rotation evaluations.2 Tools were expected to be valid and reliable measures of competency-based learning objectives, focusing on a few objectives that naturally occur during the resident-patient-supervisor encounter.

Multisource feedback (MSF) involving nonphysician evaluators and patients is an ACGME-recommended assessment method.3 Multisource feedback instruments are completed by multiple observers within a person's sphere of influence and are valuable in assessing specific behaviors or skills, especially interpersonal communication skills (ICS) and professionalism (Prof).4 However, for MSF to be considered a reliable component of a resident's performance portfolio, it must demonstrate consistent results regardless of when it is used, who uses it, and which item is assessed.

Use of the MSF in emergency medicine (EM) programs is largely untested. The only study examining MSF in EM resident training focused solely on nurses as evaluators.5 Our goal was to determine the feasibility and reliability of MSF in an EM training program.

Methods

Our study was a prospective questionnaire-based assessment of ICS and Prof. It was conducted at a suburban, university-based EM residency program. Residents in their final year of training (EM-3) were surveyed to ascertain the feasibility of implementing an MSF program and to determine the reliability of the questionnaire.

Survey Content and Administration

A previously validated MSF instrument, the Humanism Scale6 (HS), was used to obtain feedback on ICS and Prof. The original HS was reviewed by the residency administration and revised to avoid rater misinterpretation. The original HS question, “Cooperates with paramedical staff,” was refined into 2 questions: “Cooperates with nurses” and “Cooperates with ancillary medical staff.” The modified HS was pilot tested on different raters (faculty, nurses, and patients) and further revised upon feedback before full implementation. The final MSF instrument, the emergency medicine Humanism Scale (EM-HS), consisted of 9 questions with ratings on a 9-point continuum from “needs improvement” to “outstanding.” Electronic evaluation forms were distributed to faculty and nurses. Paper forms were generated for self-evaluations and patient evaluations. Both versions of the EM-HS included the resident's name and photo. The EM-HS provided to each of the rater groups was identical except that questions 1 to 3 were eliminated from the patient EM-HS.

Residents were informed at our annual orientation conference that performance feedback would be obtained from patients, staff, and faculty. Self-evaluations were collected before faculty, nurse, and patient data collection. The EM-HS was distributed to all EM nurses and faculty via e-mail list serve with a link to the electronic survey (Survey Monkey, Palo Alto, CA). Evaluators were informed that the anonymously completed evaluation would be included in the resident performance portfolio and reviewed/discussed with each resident. The survey was open for 21 days and a weekly e-mail reminder was sent via the faculty and nurses list serve.

Paper copies of the EM-HS were generated for patient evaluations. Patients were approached by the research personnel at the conclusion of an emergency department encounter and asked to complete an anonymous evaluation of the resident physician involved in their care. Surveys were collected from those patients for whom emergency department care, in its entirety, was provided by a single EM resident.

Data Analysis

All data were entered into SPSS version 18 (SPSS, Inc, Armonk, NY). Exploratory factor analyses were performed within each evaluator class to identify the dimensionality of the questions. Generalizability coefficients7 (Eρ2) were calculated to evaluate consistency within the attending and nurse evaluator classes, with residents and raters as random facets and survey items as fixed facets; a nested design was necessary for patient evaluations. Generalizability coefficients could not be calculated for self-evaluations since there was only 1 per resident. The average of the total scores provided by each evaluator class was calculated for each resident. Pearson correlations (r) were used to assess correlation between pairs of evaluator classes, using ”resident„ as the unit of analysis. Values of Eρ2 and r > 0.70 were deemed acceptable.

The study was granted a waiver of consent by the institution's Institutional Review Board.

Results

Requests to evaluate residents were sent to 16 faculty members and 65 nurses. Complete evaluations on all residents were obtained from 12 faculty members (75%) and 44 nurses (68%). Nine of 10 EM-3 residents (90%) completed a self-evaluation. Patient evaluations were obtained on 9 residents. Complete evaluations were available from 119 patients, or an average of 13 per resident.

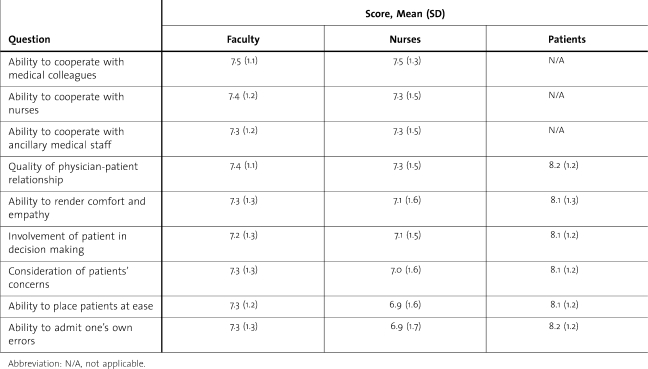

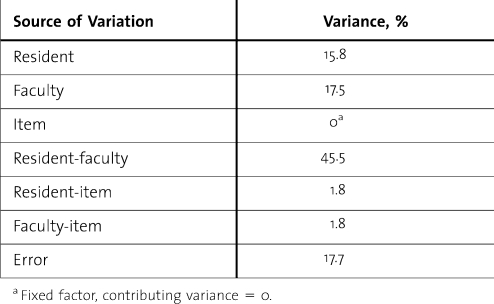

The mean score for each question per rater group is shown in table 1. The Eρ2 for faculty was 0.79. The variance components for calculating Eρ2 are shown in table 2. Nurses showed similar reliability, with an Eρ2 of 0.83, while patients demonstrated fair reliability with Eρ2 of 0.59.

Table 1.

Mean (Standard Deviation) Rater Scores by Question

Table 2.

Variance Components of the Generalizability Study of Faculty Raters

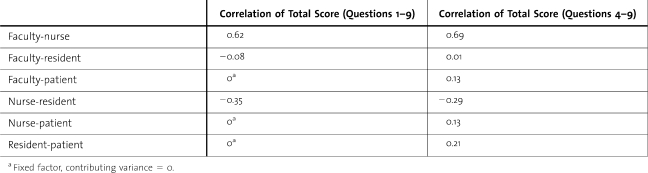

The factor analyses resulted in only a single factor for each evaluator class. Owing to the homogeneity of responses by question, correlations on an item-by-item basis were deemed unnecessary and between-rater reliability was assessed with correlations, using mean resident scores.

The interrater reliability of nurses and faculty for the mean score on all 9 questions was fair; r = 0.62 (table 3). The correlation of faculty and nurses with resident self-assessment was negative but not significant. Comparison of patient scores with faculty, nurses, and resident self-assessment was based upon the mean score of questions 4 through 9. Correlations between patients and the other evaluator classes were positive but poor and not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlations of Mean Total Resident Scores Between Evaluator Classes

Discussion

We found that using an MSF tool to assess EM resident ICS and Prof is feasible. Typically, development of an MSF tool is a time-consuming process requiring psychometric design and testing4 and a pilot period to determine reliability and establish validity.8 We used an assessment tool that had documented reliability and validity. In our experience, the electronic and paper survey setup was not time-consuming. Collection of data from nurses and faculty yielded a reasonable response rate with little more effort than sending out weekly reminders. Collection of data from patients proved to be a more arduous task, requiring assistance from trained research personnel to obtain the requisite number of patient evaluations for each of the 10 EM-3 residents. Studies suggest that acceptable reliability for the instrument and individual physician can be obtained by 8 to 10 coworkers, 8 to 10 medical colleagues, and 25 patients.9 We used 12 faculty members, 44 nurses, and approximately 13 patients to rate our residents. The results of our generalizability study indicate that MSF evaluations from 8 faculty members and 21 nurses would have provided sufficient reliability (Eρ2 > 0.70). Multisource feedback evaluations from 22 patients per resident would be needed to attain minimum reliability.

Our results suggest that the EM-HS is a reliable tool for assessing ICS and Prof of EM residents. Adequate intrarater reliability was demonstrated. Other studies have yielded similar findings. Joshi et al10 demonstrated excellent intrarater correlation for all but patient raters of obstetrics-gynecology residents. Wood et al11 demonstrated high internal consistency for all raters of radiology residents but low correlations between rater groups. In contrast, Weigelt et al12 reported that 360-degree evaluations of surgical residents provided no new information not already available from faculty evaluations. Our finding of poor interrater correlation provides further support for incorporating multiple perspectives into feedback systems. Overemphasizing agreement between raters misses one of the primary purposes of MSF: to obtain different perspectives concerning performance.

Limitations

As with all questionnaire-based studies, multiple limitations apply to our findings. Although our study used a previous validated survey, we made a minor modification to the original HS. As such, it is a new questionnaire and requires strategic development. We attempted to minimize instrument bias by following methodology for survey research.13 Despite our attempts to limit instrument bias, it is possible that the questions and/or response scales were misunderstood by raters.

Multisource feedback is especially subject to multiple memory biases such as halo effect,14 context effect, mood congruent memory bias,15 and distinctive encoding.16 Preconceptions about a resident's prior performance or previous experiences are known to influence judgment about a person or situation. We did not train raters before assessment implementation nor did we seek to determine if the rater had a recent positive or negative experience with the trainee.

We used 2 different methods to obtain MSF: paper and web based. It is unknown whether responses collected via one method are psychometrically equivalent to responses collected by a different method. There are few published studies empirically assessing measurement equivalence between web-based and paper assessment methods. It is unknown whether direct comparisons of the different MSF collection methods will result in equivalent outcomes.

Our study was not designed to assess validation of the EM-HS. Validation is a research process demonstrating that an instrument actually measures what it was designed to measure. Although Linn et al6 demonstrated reliability and validity of the HS for assessment of internal medicine residents, we cannot assert that our modified, albeit very similar, instrument maintains the same validity.

Finally, this was a single-center study of EM residents, conducted in a suburban tertiary care facility. Therefore, generalizability to other settings or specialty programs is limited.

Conclusion

The EM-HS is relatively easy to administer and provides a reliable assessment of EM resident ICS and Prof from a minimum of 8 faculty members, 21 nurses, and 22 patients. Further studies are necessary to determine validity of the EM-HS, frequency of administration, and its effect on performance.

Footnotes

All authors are at Stony Brook University Medical Center. Gregory Garra, DO, is Emergency Medicine Program Director; Andrew Wackett, MD, is Assistant Dean for Undergraduate Medical Education; and Henry Thode, PhD, is Emergency Medicine Biostatistician.

Presented at the 2010 American College of Emergency Medicine Research Forum, September 28, 2010, Las Vegas, NV.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Outcome Project. http://www.acgme.org/outcome/. Accessed May 7, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Outcome Project: toolbox of assessment methods. http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/assess/Toolbox.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Emergency Medicine. http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/110emergencymed07012007.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockyer J. Multisource feedback in the assessment of physician competencies. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(1):4–12. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340230103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tintinalli JE. Evaluation of emergency medicine residents by nurses. Acad Med. 1989;64(1):49–50. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198901000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linn LS, DiMatteo MR, Cope DW, Robbins A. Measuring physicians' humanistic attitudes, values, and behaviors. Med Care. 1987;25(6):504–513. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan RL. Generalizability Theory. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodgers KG, Manifold C. 360-degree feedback: possibilities for assessment of the ACGME core competencies for emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1300–1304. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsey PC, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Inui TS, Larson EB, LoGerfo JP. Use of peer ratings to evaluate physician performance. JAMA. 1993;269(13):1655–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi R, Ling FW, Jaeger J. Assessment of a 360-degree instrument to evaluate resident's competency in interpersonal and communication skills. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):458–463. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood J, Collins J, Burnside ES, et al. Patient, faculty, and self-assessment of radiology resident performance: a 360-degree method of measuring professionalism and interpersonal/communication skills. Acad Radiol. 2004;11(8):931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weigelt JA, Brasel K. J, Bragg D, Simpson D. The 360-degree evaluation: increased work with little return. Curr Surg. 2004;61(6):616–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Totten VY, Panacek EA, Price D. Basics of survey research (part 14), survey research methodology: designing the survey instrument. Air Med J. 1999;18(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/s1067-991x(99)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorndike EL. A constant error in psychological ratings. J Appl Psychol. 1920;4:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rholes WS, Riskind JH, Lane JW. Emotional states and memory biases: effects of cognitive priming and mood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:91–99. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantyla T. Recollection of faces: remembering differences and knowing similarities. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1997;23(5):1203–1216. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.23.5.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]