Abstract

Post treatment relapse to uncontrolled alcohol use is common. More cost-effective approaches are needed. We believe currently available communication technology can use existing models for relapse prevention to cost-effectively improve long-term relapse prevention. This paper describes: 1) research-based elements of alcohol related relapse prevention and how they can be encompassed in Self Determination Theory (SDT) and Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention Model, 2) how technology could help address the needs of people seeking recovery, 3) a technology-based prototype, organized around Self Determination Theory and Marlatt’s model and 4) how we are testing a system based on the ideas in this article and related ethical and operational considerations.

Keywords: technology, relapse prevention, alcohol dependence, mobile phone, cell phone

An estimated 17.6 million persons (7.1 percent of the population aged 12 or older) are classified with alcohol use disorders (SAMHSA, 2008; Grant & Dawson, 2006). Of these, 3.9 million persons received some kind of treatment for alcohol or illicit drugs in 2005. Social costs of alcohol abuse and dependence in the U.S. are estimated to be approximately $184.6 billion per year (Harwood, 2000).

Despite numerous advances in the treatment of alcoholism, relapse to heavy or uncontrolled use remains common – sometimes as high as 80% (Bradizza, Stasiewicz & Paas, 2006; Brownell, Marlatt, Lichtenstein, & Wilson, 1986; Dennis, Scott & Funk, 2003; Donovan, 1996; Lowman, Allen & Stout, 1996; McKay & Weiss, 2001; McLellan, 2002; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004; Mueller et al, 2007). Relapse reduces quality of life and strains family relationships while abstinence improves emotional and family/social functioning (Etner, 2006). Furthermore abuse of alcohol and other drugs is associated with serious public health and safety problems (McLellan, Lewis, O’Brien, & Kleber, 2000), exacts great societal costs including higher crime (Etner, 2006), elevates healthcare costs (Etner, 2006), and reduces productivity (Slaymaker & Owen, 2006; Hoffman, DeHart & Fulerson, 1993).

Although most experts currently consider alcoholism to be a chronic disease, providers do not typically offer ongoing support for relapse prevention after patients complete their treatment. While aftercare appointments may be set up, ongoing monitoring or “check-ups” to ensure compliance with treatment recommendations, which are common with other chronic disorders, are rare in addiction (McLellan, Lewis, O’Brien, & Kleber, 2000; While, Boyle & Loveland, 2002). Most research supports the effectiveness of continuing care for alcohol and drug abusers (McKay, 2005), finding that prolonged participation is associated with better outcomes (McLellan, McKay, Forman, Cacciola, & Kemp, 2005; Simpson, 2004). Unfortunately, because the alcohol treatment infrastructure is financially overburdened, labor intensive, and unstable, continuing care is not widely available (McLellan, Carise & Kleber, 2003).

Based on the above research, it is clear that new, more cost-effective strategies are needed to improve access to continuing care and help achieve its promise. Using past research as a guide, we argue in this article that currently available mobile communication technologies can be used to cost effectively complement and extend existing models for relapse prevention services to improve long-term outcomes for individuals struggling with alcohol dependence disorders. First, we summarize what previous research suggests are essential elements of ongoing relapse prevention programs and how these constructs can be encompassed within the frameworks of Self Determination Theory (SDT) and Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention model and how they are relevant to the nature of alcoholism. Second, we describe how technology could be used to address the needs of people attempting to achieve a long-term recovery and complement the way services are currently offered. Third, we explicate how our proposed technology-based prototype services, organized around constructs specified in Self Determination Theory, align with stages specified by Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention model. Finally, we describe steps that are currently being undertaken to test the ideas put forth in this article and discuss both ethical and operational considerations that are being addressed in launching this initiative.

Elements of Successful Relapse Prevention Programs

It should be noted that some people have spontaneous recovery and avoid relapse on their own (cf. Shorkey 2004; Klingemann and Sobell 2001). However, for the many who do not, there is abundant evidence that inadequate coping strategies, a lack of social support, and flagging motivation, among other factors, are associated with heightened likelihood of relapse. We also acknowledge that these are only some of the factors associated with relapse. Our model is focused more on cognitive, affective, social and environmental influences on relapse and is not a model of neurobiological, genetic or other bases of addiction and relapse.

Below we synthesize information on the nature of alcoholism, the factors that contribute to a successful recovery, and present a theory of behavior change and motivation – Self Determination Theory – that serves as our organizing framework for understanding how these constructs work together to influence treatment outcomes.

Coping and competence

Research has shown that execution of coping behaviors is associated with decreased likelihood of relapse to alcohol use. (Anderson, Ramo & Brown, 2006; Maisto, Zywiak, and Connors, 2006; Shiffman, 1984, 1986). An increased tendency to engage in effective, adaptive coping is associated with: 1) low levels of an avoidant coping style, with avoidant coping being characterized by distraction or escape rather than active, problem-focused coping (see Chung et al., 2001, as well as Moos and Moos, 2006); and, 2) high levels of self-competence or self-efficacy appraisals (Gwaltney, Shiffman, Balabanis, & Paty, 2005; Litt, Kaden, Kabela-Cormier, & Petry, 2008; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). The importance of coping execution is shown by evidence that routine self-monitoring of triggers of alcohol use (Helzer, Badger, Rose, Mongeon, & Searles, 2002; Stout, Rubin, Zwick, Zywiak, & Bellino, 1999) as well as reactive and proactive coping execution (e.g., urge coping or the avoidance of people, places and things associated with prior alcohol using experiences) lead to sustained abstinence and early detection of alcohol use, which permits re-engagement in treatment to forestall an escalation of abuse (Baker & Kirschenbaum, 1998; Carroll, 1996; Dennis, Scott & Funk, 2003; Irvin, Bowers, Dunn & Wang, 1999; Godley, Godley, Dennis, Funk, & Passetti, 2002; Miller, 1987; Stalcup, Christian, Stalcup, Brown, & Galloway, 2006). Additionally, prior research has highlighted the sorts of coping behaviors that are most beneficial, including the anticipation of high-risk contexts, plans to mitigate these risks, engagement in active behavioral or cognitive coping strategies when confronted by acute crises such as urges and negative affect. It also highlights what is not beneficial, including a tendency to delay or avoid active coping (an avoidant coping style). Unfortunately, many individuals will not engage in problem solving/coping without being prompted to do so (Davis & Glaros, 1986; Larimer, Palmer & Marlatt, 1999).

Individuals with alcohol use disorders may fail to engage in adaptive monitoring and coping for multiple reasons. For instance, over time, routine daily activities become automatic; i.e., they tend to be elicited and executed without significant awareness (e.g., Tiffany et al., 1990). Automatic processing may be contrasted with controlled or effortful processing, which is characterized by awareness and controllability. Without awareness, there is little opportunity for conscious, deliberative planning to influence people to change their ways. In other words, over time, the recovering substance abuser may fall in with old crowds and pick up old behaviors associated with alcohol use, without thinking about the potential risks or alternatives (Curtin et al., 2006; McCarthy et al., in press).

The substance abuser’s execution of effective coping may also be thwarted by other factors. To the extent that the substance abuser fails to avoid temptation situations (e.g., places or behaviors associated with prior alcohol use), these situations will tend to elicit alcohol use behaviors via associative (learning) mechanisms. If the person is to avoid alcohol use, the possibility of alcohol use must enter his/her awareness so that it becomes a choice and not a “reflex.” That is, attentional and cognitive control processes/resources must interrupt the automatic sequence of alcohol self-administration behaviors, introducing it to conscious awareness, and then applying problem solving or coping processing so that other responses may be substituted for it (e.g., generate alternatives, justify a delay of gratification, and so on: Curtin et al., 2006; McCarthy et al., in press; Tiffany et al., 1990). Functional or adaptive decisions might include future avoidance of the alcohol cues/temptation situation, engagement of a pleasant alternative behavior, or seeking positive social support that will enhance the motivation to maintain abstinence. There is, in fact, considerable evidence that coping response processing and execution predicts superior outcomes (Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004; Burgess, Brown & Kahler et al., 2002; Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Hickcox, 1996).

Alcoholics may also have cognitive control deficits relative to other individuals. That is, they don’t interrupt automatic behaviors as well (are “impulsive” and less able to inhibit behaviors in response to provocative cues), and may have neuropsychological deficits that may interfere with adaptive problem solving (e.g., Courtney & Polich, 2009; Stout et al., 2005; Woods et al., 2005). Cognitive control resources are capacity limited, but capacity may be especially limited for substance users (e.g., Nigg et al., 2004).

Given these features of motivation and information processing among individuals with alcohol use disorders, why might a mobile, technology-based system aid a person striving to attain or maintain abstinence? Such a system can be engineered to serve as an electronic prosthesis for the alcohol abuser’s cognitive control deficits. For instance, the system can monitor the individual’s activities and locations in order to detect risks that may be opaque to the individual. Moreover, simply by probing behavior and context, the system could heighten the individual’s awareness of danger, and recruit cognitive control resources. The system could also prompt planning to decrease the likelihood of future alcohol use. In addition, the system could enhance the individual’s ability to cope with temptation to use once it enters awareness; it could suggest more or better coping responses than would occur to the person as s/he battles a strong motivation to use alcohol. Further, the system may make a greater variety of coping responses available. For instance, the system may give the person ready access to counseling or advice (feedback would, among other things, add the counselor’s cognitive control resources to the substance abusers) or social support. It might also provide access to information processing supports such as decision aids that bolster the person’s own decision making abilities. Another such aid would be games that occupy mental workspace. This could be useful, as such games could displace urge processing (given capacity limitations noted earlier).

In summary, alcoholism involves the patient’s struggle to exert cognitive control over behaviors that are not anticipated, and that challenge the person’s cognitive control resources because of: intrinsic capacity limitations, the absence of attractive alternative responses, and fundamental ambivalence regarding the relative values of immediate vs. delayed outcomes. An effective technology-based support system could provide resources that address all of these needs.

Social support

Research indicates that lack of actual and perceived positive social support or the existence of social pressure is associated with relapse vulnerability (Beattie & Longabaugh, 1999; Broome, Simpson & Joe, 2002; Havassy, Hall & Wasserman, 1991; McMahon,, 2001; and Zywiak, Westerberg, Connors, & Miasto, 2003). People in recovery who remain involved with self-help groups have superior abstinence outcomes (Dobkin, De, Paraherakis, & Gill, 2002; Finney, Moos & Mewborn, 1980; Oimette et al., 2001; Oimette, Moos, & Finney, 2003; Schradle & Dougher, 1985). One way to prevent relapse is to help people early in recovery feel connected with others in alcohol-free recreational activities (Meyers, Smith, & Lash, 2003; Schottenfeld, Pantalon, Chawarski, & Pakes, 2000). Furthermore, research suggests that relapse can be reduced if people in recovery can reach case managers to help with service access, monitor for lapse cues, and provide social support for coping with challenging issues (Godley, Godley, Dennis et al., 2002; McLellan, Hagan, Levine et al., 1999; Rapp, Siegal, & Fisher, 1992).

Technology can be used in several ways to improve social support to prevent relapse. It can allow people in recovery to talk with and support one another through online support groups and activities. It can also provide a variety of ways to easily reach individuals such as clinicians or significant others (e.g., text messages, phone calls, emails).

Autonomous motivation

Clearly, there is substantial evidence that self-reported motivation is related to abstinence outcomes (Piasecki, Fiore, McCarthy, & Baker, 2002; Witkiewitz, van der Maas, Hufford, & Marlatt, 2007) and a reduced sense of intrinsic or autonomous motivation is associated with relapse (Curry, Wagner & Grothaus, 1990; McBride, Curry, Stephens et al., 1994;, Miller & Rollnick, 1991; Williams, Gagne, Ryan & Deci, 2002; Williams, Freedman & Deci, 1998). Fortunately, research also shows that motivation, in general, and intrinsic motivation, in particular, can be increased through treatment. For example, mounting evidence shows that personalized or tailored information and motivational interviewing approaches improve both motivation level and outcomes for people attempting to reduce problem drinking or other forms of alcohol use (Cunningham, Humphreys, Kypri & van Mierlo, 2006; Hester & Delaney, 1997; Hester, Squires, & Delaney, 2005; Hester & Miller, 2006; Koski-Jannes, Cunningham, Tolonen, & Bothas, 2006).

Technology offers the potential to provide immediate multi-media 1) access to personal stories of the struggles and successes of others who have dealt with alcoholism, 2) access to decision aids that help a user think through key issues in their lives, 3) access to an inventory of practical tools that can ease the process of relapse prevention and 4) that do so in a respectful style that does not alienate the user because it can give them options rather than telling them what to do.

Self-Determination Theory and Cognitive-Behavioral Relapse Prevention

The targeting of the three major dimensions or change mechanisms discussed above (coping competence, social support, and autonomous motivation) aligns with tenets of Self-Determination Theory (SDT). Indeed, SDT posits that satisfaction of three fundamental needs contributes to adaptive functioning: i.e., perceived competence, a feeling of relatedness (feeling connected to others), and autonomous motivation (feeling internally motivated and un-coerced in one’s actions) (Deci & Ryan, 2006). Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) also makes the case that quality of life is largely a matter of the degree to which three basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are met. Many studies have related satisfaction of these basic needs to well being and quality of life (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

The three change mechanisms discussed above are also consistent with Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention model. Marlatt’s Relapse Prevention Model is widely accepted by addiction treatment opinion leaders (Maisto et al, 1996; Stout et al, 1996; McKay 1999), especially when used to inform the treatment of alcoholism (Irvin et al., 1999), and is not mutually exclusive with the more general SDT. The cognitive behavioral relapse-prevention model suggests that both immediate determinants (high-risk situations, lack of coping response, decreased self efficacy, and abstinence violation effects) and covert antecedents (lifestyle imbalances, urges and cravings) can lead to relapse. The model includes interventions that address each of the dimensions that precede relapse, suggesting both specific (e.g., identifying high-risk situations, managing lapses) and global (e.g., balancing lifestyle, pursuing positive and rewarding activities) strategies.

Below we discuss our previous work in developing and evaluating technology-based information and support systems to help people cope with illness. Next, building on these experiences, we describe how a mobile, technology-based system, grounded in the change mechanisms and theoretical models of relapse described above, could be used to reduce the likelihood of relapse among people in recovery by (1) prompting coping behaviors, (2) facilitating access to social support and (3) encouraging autonomous motivation abstinence, across the covert antecedents and immediate determinates (lifestyle imbalance, desire for indulgence, etc.) suggested by Marlatt’s model.

Feasibility of a Mobile, Technology-Based Relapse Prevention System

Based on the above review of extant research, we propose that numerous evidence-based features could be integrated into a comprehensive technology-based solution to improve long-term recovery outcomes in a cost-effective manner. The team behind this initiative is comprised of individuals working with the Network for Improvement of Addiction Treatment (NIATx), which delivers quality improvement interventions to nearly 1000 substance abuse treatment providers across the United States (see NIATx.net) and the developers of the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS), a computer system designed to help people cope with various health concerns. Both NIATx and CHESS reside within one research center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the United States.

CHESS is an umbrella name for several computer based eHealth systems that our research team has developed and tested (http://chess.wisc.edu). CHESS programs provide information, adherence strategies, decision-making tools and support services in attractive, easy-to-use formats. Content has typically been presented at a 6th grade reading level and focused on specific needs identified in studies of the target population. Compared to the unrestricted Internet, the most important strength of CHESS may be its closed, guided universe of tailored information and support options in an integrated package with efficient navigation eliminating the need for complicated search and discovery. ACHESS (Addiction CHESS), the focus of the research reported below, differs from previous CHESS programs in two important ways. 1) This project is designed to meet the needs of people with reading levels lower than 6th grade by providing audio and video access to material. 2) Instead of functioning on a desktop or laptop computer, it will use a smart phone to greatly expand its mobility.

For the last six years, our research center has been one of four National Cancer Institute designated Centers of Excellence in Cancer Communications Research because of our work with CHESS. Historically, we have emphasized randomized trials to test the effectiveness of such systems on cancer patients (we have six ongoing at this time). We also have three such trials completed or underway for improving control of a chronic disease. Randomized clinical trials have repeatedly found that CHESS improves quality of life and produces behavior change for people facing various health issues. The empirical results are summarized below:

Needs Assessment

We have extensive experience conducting needs assessments as well as in developing and testing CHESS systems to meet those needs (Gustafson et al 1987, 1993, 2001a & b, Pingree et al 1996, Shaw, et al 2000, and Boberg et al 2003). For example, to inform ACHESS, we conducted a multi-site study to identify and prioritize needs of alcohol and other drug dependent patients, their families, counselors, child welfare and criminal justice personnel and primary care physicians. We started with focus groups of 48 people that included needs identification and reaction to various technological support components for ACHESS. A survey instrument was developed to assess the importance of and satisfaction with how well each need was currently being met in their lives. Fifteen treatment agencies participating with NIATx distributed the survey to people in recovery enrolled in intensive outpatient programs, their families and related professional personnel. The top identified needs in priority order were to help patients: 1) understand what addiction really is, 2) know how to stop a relapse, 3) be prepared to function in society upon reentry into their normal, everyday lives following the more intensive therapy they receive early in recovery, 4) obtain truly individualized treatment, 5) find motivation to stay in treatment and take it seriously, 6) choose a treatment that is most likely to succeed, 7) improve ability to resist temptations, 8) know the things that makes one vulnerable to relapse and 9) know the warning signs of impending relapse. As described below, ACHESS is designed to meet those needs.

BARN

Our research on computer-based systems to directly support people in need began with a grant in 1980 from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to develop a personal computer-based system to support at-risk teenagers as they dealt with issues such as smoking, illicit drug use, sex, etc. (Gustafson et al., 1987). We created a computer-based system called BARNY (Body Awareness Research Network) offering some (but not all) of the features in CHESS today. An evaluation demonstrated that while the system was widely accepted and used, the program was not successful in preventing risk-taking behavior (Bosworth, Gustafson & Hawkins, 1994). However, BARN was able to help teenagers who had already engaged in such behaviors (e.g., getting sexually active teenagers to adopt more safe-sex behaviors). These experiences and the advent of more sophisticated computer systems (e.g. ability to offer discussion groups and access to the Web) led us to believe that we could help patients facing serious medical problems.

Impact on HIV Infected People

Two hundred HIV infected people were randomly assigned to either no intervention (control) or CHESS on a desktop computer in their homes. Subjects were surveyed at pre-test and 2 and 5-month post-tests. The 100 experimental subjects used CHESS over 16,000 times during the first nine weeks of the study. Demographic characteristics, HIV illness stage and health status had little relation to CHESS use. Five of eight quality of life measures (activity, reduced negative emotions, social support, cognition, and participation in healthcare) significantly improved in those having CHESS access compared to those who did not. Average time spent with physicians dropped significantly for CHESS users, as did average length of hospital stay.

Impact on Disadvantaged People

An National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded randomized controlled trial of 346 women under age 60 with breast cancer, one-third of these including underserved minorities, evaluated CHESS impact over a 6-month period. Compared to controls, CHESS patients participated more actively in their healthcare. They also perceived themselves to be more competent in handling information. Four of six quality of life measures showed significant interactions as did measures of participation in healthcare. Disadvantaged women benefited from CHESS more than white, privately insured women. In general, poor, minority CHESS users moved to levels similar to (and statistically not different from) those of middle class white women (Gustafson et al, 2001).

Feasibility of Reaching Underserved Populations

A population study was designed to overcome the digital divide by testing interventions to increase access to and use of CHESS. Using several contact models (e.g., Medicaid patient lists, Cancer Information Service, Public Health Departments, media, etc.), CHESS was offered to two full populations of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer who were living at or below 250% of poverty and will be referred to as “underserved” (Gustafson et al 2005). We found that given the opportunity to access a health system like CHESS, the underserved will use it, and 40% of eligible patients accepted CHESS and used it as much if not more than their more advantaged counterparts. In addition, access to CHESS correlated with quality of life improvement and greater participation in their healthcare. However, we also found that 47% of our urban and 20% of our rural adult population were functionally illiterate. This led us to design the audio-based CHESS alternative that is a key focus of ACHESS.

CHESS Effects on Asthma Control

An NIH grant funded a randomized trial of a personal computer (CHESS) and nurse case manager to support parents of children (ages 4–12) with moderate to severe asthma. Parents were randomly assigned to 12 months of standard care control or computer-based CHESS in their homes coupled with an asthma nurse case manager. We recruited 305 subjects (50% Medicaid families) with less than a 15% drop out. The CHESS group received tailored information based on bi-weekly “check ins” and links to CHESS material created by their nurse case managers following phone contacts. There was no difference between control and experimental groups at baseline. But, CHESS patients were practically (effect size > .40) and significantly better on all three follow-up tests of asthma control. We learned several things to inform our work with alcoholics: a) home-based personal computer means that CHESS is only available at home potentially limiting its usefulness elsewhere, b) case managers can make a significant difference if they intervene before the crisis begins, c) patients might manage their disease more effectively if they had just-in-time support. These experiences led us to believe that chronic disease control might be improved by a mobile smart phone system (M-CHESS) with easy-to-access, just-in-time information, tools, reminders and tracking as well as support and advice from peers, and case managers. This mobile tool is currently being evaluated under a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research in a randomized clinical trial with inner city teenagers with moderate to severe asthma.

Smoking Cessation for Teens and Adults

Two NIH-funded randomized trials tested the effects of CHESS programs to help smokers quit. One project involving 140 teen smokers was conducted jointly with the Mayo clinic. It found that CHESS produced a significant reduction in average number of days smoked compared to a control group (Patten et al., 2006). Another CHESS smoking cessation program developed in partnership with Wisconsin’s Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention was aimed at helping adults quit. The number of times participants used CHESS per week was significantly related to abstinence at both end of treatment and at the 6-month follow-up indicating that CHESS makes a difference for people who use it (Japuntich et al., 2006). However, subject interviews suggested that using a personal computer for information and support was inconvenient and not available when it was most needed. This experience also played a role in deciding to develop the mobile ACHESS system.

CHESS Compared to the Internet

A National Library of Medicine (NLM) funded grant compared CHESS’ use and impact to unguided access to the Internet among recently diagnosed breast cancer patients. We provided the same computers and amount of training to both study arms (N=257). Internet users were linked to six high-quality breast cancer web sites. We compared CHESS and Internet users on quality of life, social support, and health information competence at 2, 4 and 9 months (5 months after computers were removed). CHESS subjects logged on to the computer more than Internet subjects and accessed more health resources. The Internet group used non-health sites much more than health sites. Internet subjects experienced no better outcomes than controls at any of the three time points. CHESS subjects had greater social support at 2 and 4 months and higher scores on all outcomes at nine months. CHESS subjects also scored higher than subjects assigned to an Internet-only condition. These results provided encouraging evidence (albeit from cancer patients and not alcoholics) that giving people who are dealing with alcoholism health challenges access to the Internet is unlikely to have the same effect as the system we are developing (Gustafson et al., 2008).

Planned Application of CHESS to Alcoholism

We now are in the first year of a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) funded grant to extend our work with CHESS to develop an integrated relapse-prevention system named ‘Alcohol-Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System’ (ACHESS). The ACHESS intervention is explicitly designed to address the three constructs described above (coping competence, social support, and autonomous motivation).

Addressing the range of functions described above to enhance post-treatment discharge recovery would be prohibitively costly, impractical, and labor-intensive using procedures currently available in the alcohol treatment field today. However, a technology-based system delivered via smart phones might overcome these barriers to implementation. Such a system could offer people in recovery support whenever and wherever it is needed, and have the potential to reduce costs and improve the effectiveness of existing alcohol treatment programs.

We argue in this article that addressing each of the above mentioned constructs related to preventing relapse and extending continuing care in a cost-effective manner could be accomplished using wireless Internet-enabled mobile phone technology that is readily available today. ACHESS would integrate these services to offer people in recovery a comprehensive, scientifically informed intervention that addresses principal relapse risks, and reduces the likelihood of relapse as well as the negative consequences associated with risky drinking behavior (Hester & Miller, 2006).

Preliminary studies on people using technology-based services for managing recovery from alcoholism are encouraging. First, many people facing substance abuse issues have an interest in self-help tools to evaluate their behaviors; computerized interventions have been identified as being attractive for this purpose (Cunningham, Wild, & Walsh, 1999). Additionally, research indicates that self-administered questionnaires about addictive behavior can be a feasible alternative to interviews conducted by addiction professionals. In fact, patients acknowledge more alcohol use and psychiatric symptoms through online questionnaires than through face-to-face interviews (Rosen, Henson, Finney & Moos, 2000). Furthermore, previous research indicates that mobile technology (e.g., Interactive Voice Response - IVR) can be an effective way to collect data from people diagnosed with substance use disorders (Simpson, Kivlahan, Bush, & McFall, 2005), which can then be used to trigger supports as needed to help people in recovery avoid a relapse. Indeed, compliance in these studies using mobile devices has been very high with people responding to over 93% of calls made (Searles, Helzer, Rose, & Badger, 2002). As excessive consumption of alcohol is associated with marked deficits in cognitive functioning (Sullivan, Rosenbloom, & Pfefferbaum, 2000) including visual scanning needed for reading (Beatty, Hames, Blanco, Nixon, & Tivis, 1996), it is also believed that audiovisual capabilities will help some users of this system more easily access the information and support they need to stay abstinent and avoid risky drinking.

Explicating a Mobile, Technology-Based Relapse Prevention System

As referred to above, the design of the ACHESS relapse prevention system is influenced by both SDT and Marlatt’s Relapse Prevention model, which build on and integrate a rich tradition of social sciences research related to behavior change (Bandura, 1977), social learning (Rhodes, Fishbein, & Reis, 1977), persuasive communication (Hovland, Janis & Kelley, 1964), motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), behavioral intent (Azjen & Fishbein, 1977), and stages of change (Prochaska and DiClemente, 1983). SDT focuses on developing competence, relatedness and autonomy. ACHESS will employ these concepts in the following ways to prevent relapse: 1) develop/maintain autonomous motivation to prevent relapse (autonomy supportiveness). 2) offer resources to cope with pressures to relapse, e.g., cravings, withdrawal symptoms, high risk situations (competence); and, 3) provide access to social support to persevere (relatedness).

The ACHESS prototype is not only consistent with important theory and research evidence, but, as described above, is also informed by input from individuals suffering from alcohol and other substance use disorders, their family members, and thought leaders from addiction treatment, health informatics and other allied disciplines (Gustafson, Palesh, & Plsec et al., 2005). A series of planning meetings identified patient, family and provider needs as well as technology-based innovations that could address these needs.

The ACHESS system is compatible with the view that addiction is a chronic, relapsing disorder. We anticipate that days of risky drinking should be reduced by interrupting the advancement of stages preceding relapse (Larimer, Palmer, & Marlatt, 1999), which will be mediated by social support, autonomous motivation, competence or coping strategies (Zywiak, Stout, Longabaugh et al., 2006). ACHESS will be delivered on a smart phone, offering digital voice services along with a number of other features including text messaging, Web access, GPS, voice recognition and video capabilities. The optimal functioning of ACHESS also assumes access to the newer generation 3G cellular networks that provide fast access to the Internet and other mobile data services. The system will: transfer data from the phone to a computer accessible by the patient’s counselor or care manager, have sufficient memory to store static content and global positioning system (GPS) technology that provides location-detection services. The system is designed for people in recovery being discharged from residential care or individuals enrolled in or graduating from intensive outpatient services. In both cases, a counselor would train a user how to use ACHESS. Specific relapse prevention services on ACHESS will include the following:

Basic Services

Though the focus of this paper is on the more innovative features of our proposed mobile relapse prevention system, a brief description of the services that will be adapted from previous computer–based versions of CHESS (basic services) follows. After that, we offer more detailed descriptions of those services that are unique to the smart phone system currently being developed.

Using Discussion Groups, patients can exchange emotional support and information with other ACHESS users via online bulletin board support groups. Ask an Expert allows ACHESS users to receive responses within 24 hours (weekdays) from experts in addiction to request information and advice. Responses to questions of general interest are rendered anonymous and placed in Open Expert for all users to view. ACHESS Personal Stories will be professionally written as well as video accounts based on interviews of patients and family members focused on recovery experiences such as reasons for and ambivalence about relapse prevention, strategies to overcome barriers to addiction management, what they would do differently, and how they coped with challenges. Instant Library will allow users to access detailed summaries of approximately 300 articles chapters and manuals on addiction management. Medication Resource will include information about addiction pharmacotherapies, side effects and ways to reduce and barriers to adherence (e.g., forgetting to take medications, daily techniques to remember to take medications, family or social supports in observing medication adherence with positive reinforcement, money and transportation to get medication). The Questions & Answers resource consists of brief answers to 260 frequently asked questions about addiction such as “Ways to overcome symptoms,” and “How to find wrap-around services” with links to other CHESS services offering more detailed support. Web Links allows patients to access only approved addiction-related web sites (and specific pages within sites) with introductions covering how the site might help and its strengths and weaknesses. ACHESS Journaling allows patients to either write or voice record their personal recovery experiences, with the option of later reviewing them with their counselor. Easing Distress is a computerized cognitive behavior therapy program currently operating on several CHESS modules. It will be adapted to the smart phone to help people cope with harmful thoughts that can stymie efforts to prevent relapse. It helps assess logical errors, attributional style and tendencies to exaggerate distress, and offers practical exercises to improve cognitive problems solving skills. Development of all services is taking into account the smaller screens available on mobile devices and therefore developing content and designing interfaces so they are optimized for a handheld device.

Below we describe the new, more innovative services that are being developed specifically for the ACHESS mobile relapse-prevention system.

Healthy Events Newsletter

As mentioned previously, one way to prevent relapse is to help people in early recovery feel connected to others in drug and alcohol-free recreational activities (Meyers, Smith & Lash, 2003), and this assistance is particularly needed in early recovery when there may be little reward to abstaining from alcohol. ACHESS will inform individuals in recovery about these healthy events via their mobile smart phone. People’s calendars will be automatically populated with events that are consistent with healthy activities that they have previously expressed an interest in when setting up their preferences for the system. This will enhance autonomy for people in recovery by appealing to their own internal motivations for selecting recovery-friendly activities they find pleasurable or interesting. Using social networking technology, this service also has the capability to automatically link users to other individuals in recovery who share similar interests, which will help facilitate companionship and enhance feelings of relatedness while participating in activities likely to contribute to a lasting recovery.

Electronic Care Manager

Using one-on-one counselors has improved treatment outcomes in several studies (Godley, Godley, Dennis et al., 2002; McLellen, Hagen, Levine et al,. 1999; Rapp, Siegel & Fisher, 1992; Sullivan, Wolf & Hartmann, 1992). Additionally, electronic communication with a case manager has been shown to support behavioral change efforts of people with chronic diseases (Tufano & Karras, 2005) including addictions (Alemi, Stephens, Javalghi et al., 1996). Research suggests that ongoing program contact can be beneficial as it provides complementary social support, in addition to teaching coping skills and providing prompts. The Care Management feature of ACHESS is designed to increase both competence and confidence regarding coping, and also reduce reliance on avoidant coping strategies. Because the content of ACHESS is designed according to the principles of SDT (Williams, Gagne, Ryan & Deci, 2002) and motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 1991), it is intended to support behavior change or maintenance via the patient’s perception that his or her coping actions directly serve his/her intrinsic goals.

Operationally, conference calls will be scheduled with the patient’s Care Manager when he or she first gets access to the intervention. This service is intended to be a low-cost way for treatment providers to stay in touch with clients and help people avoid the relapses that are common with alcohol-dependence disorders. Some states (e.g., Rhode Island) have already begun to pay for continuing care and to reimburse counselors for such work. Before each scheduled call, ACHESS will (with patient permission) email a report to the counselor on ACHESS resources used, topics addressed and longitudinal graphs illustrating their status over time since the last contact (e.g., negative affect, symptom-free days, symptoms experienced, and adherence to therapeutic goals such as alcohol free days, as well as a list of issues the patient wishes to address). The Care Manager contacts will begin by reviewing the reports and providing education (e.g., dealing with a particular trigger) tailored to their needs. Following scheduled calls, the Care Manager will create links to relevant ACHESS material and place them on ACHESS for patients to access. The patient and Care Manager can call each other via a pre-programmed button on their phones. Care Managers can be notified on their phone any time the patient’s status on certain variables’ exceeds agreed upon thresholds.

Tailored Information

As referred to above, providing the most relevant information to people in recovery is challenging because of the diversity of treatment programs for addiction, and because no single treatment is likely to be completely appropriate for each individual. Additionally, people with addiction disorders often have different psychological characteristics, co-occurring physical or mental problems and come from diverse social environments. Therefore, it follows that many patients in recovery may benefit from personalized treatment. However, providing the most relevant interventions to support people in recovery is challenging because of the costs of sustaining such interventions and because optimal outcomes require tailoring to each person’s unique psychological, physical and social circumstances such as self-efficacy (Maisto, Zywiak & Connors, 2006), perceived risk for relapse (Walton, Reischl, & Ramanthan, 1995), and decisional balance between perceived positive and negative outcomes of substance use (Miller & Rolnick, 1995). Fortunately, information technology makes it possible to provide tailored interventions to each person in a cost effective manner (Kreuter, Bull, Clark & Oswald, 1999; Kreuter & Wray, 2003; Doupi & van der Lei, 2003).

Unfortunately, many people in recovery can get placed in “one-size-fits-all” treatment based upon program philosophy, or what programs are available and affordable. Not surprisingly, however, the superiority of tailored education messages over general material has been supported across a variety of health education domains (Borland, Balmford & Hunt, 2004; Strecher et al., 1994). Rather than provide individuals generic information about addiction, ACHESS will personalize information so people in recovery are proactively delivered only the information that is most relevant to their situation. ACHESS will tailor information by assessing patients about their intrinsic goals and situation while providing tailored options consistent with the principles of motivational interviewing to enhance autonomous motivation.

High Risk Patient Locator

The High-Risk Patient Locator uses Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to track when somebody in recovery is approaching an area where he or she has traditionally obtained alcohol so they can be contacted to receive support to work through what might be a high-risk situation for relapse. To activate the service, the individual in recovery would voluntarily register places where he or she has regularly obtained alcohol in the past and also who they would like to be alerted of their physical whereabouts if they are approaching a pre-designated high-risk location for relapse as a part of the recovery plan. ACHESS will provide people in recovery choices about what actions are triggered when approaching locations that they have specified as high-risk. First, the person in recovery will receive an automated, computer-generated alert to raise his or her consciousness about the situation and provide the person an opportunity to ask for additional support if needed. Second, they can configure the service so that selected supporters (e.g., family members, peer sponsors, or treatment professionals) are alerted when the person in recovery is approaching a high-risk location and offer to talk to them on the phone or meet in person if they need additional help.

Alerts/Reminders

Research shows that one of the greatest predictors of a successful recovery is retention in treatment, and longer treatment episodes are associated with better outcomes (Simpson, Joe, & Rowan-Szai, 1999). However, many people in recovery do not reliably show up to appointments or meetings. Many will end up relapsing back to using alcohol when they stop participating in treatment services, or when use begins, they stop attending treatment. Therefore, ACHESS will use the smart phones to deliver text or voice reminders of upcoming appointments and meetings. Such reminders might significantly reduce the number of missed appointments and could prompt two-way communication so that an appointment may be rescheduled. Reminders enhance a person’s sense of competence by providing support needed to work recovery-related activities into their daily routine. Other types of periodic alerts can also be set up such as celebrating new recovery milestones (e.g., 30-days sober) further reinforcing a person’s sense of agency in the recovery process or offering useful information such as a recovery ‘tip of the day’ that could spur proactive coping or remind the individual of his/her motives for abstinence and recovery.

Ongoing Mini Assessments

Relapse can be triggered by a variety of factors including environmental cues, social pressure, emotional states, attitudes and withdrawal symptoms. At periodic and random intervals, ACHESS will deliver ecological momentary assessments (short surveys) to determine if any of the above factors are at levels that may warrant additional support. Such proactive monitoring, collecting data with interactive voice recognition or text technology, can detect early warning signs and make the person in recovery aware of possible triggers as well as offer different options for managing the situation to prevent a relapse.

Panic Button

If there is need for immediate help to avoid an imminent relapse (e.g., if urges and cravings become severe and they want assistance), patients could press the smart phone’s “panic button.” The GPS location tracker could also figuratively push the panic button if the subject is approaching a high-risk trigger location. The rescue plan established during setup with the ACHESS system would be initiated, possibly including automated reminders to the patient (partly as a diversionary action but also to identify what kind of help would be most valuable) and computer-generated alerts to key people (e.g., treatment agency, 12-step members, faith providers, counselor, family, friend) who may reach out to the patient via phone or in person. In the vernacular of Marlatt’s model, the panic button provides a monitoring strategy for high-risk situations and initiates support to prevent a relapse or escalation to continued use.

Check-In

Initially on a daily basis, but weekly as the patient meets therapeutic goals (e.g., continued abstinence), ACHESS will display a brief survey on the phone’s screen (with audio overlay if requested) to obtain patient data on: negative affect; lifestyle balance; recent alcohol and other drug use; progress toward therapeutic goals and home/work/educational responsibilities entered at setup; upcoming high-risk events and other potential triggers; motivation to stay abstinent, as well as desire to re-enter treatment; and, via open-ended questions, any specific patient concerns. Once a month, ACHESS will also collect data on other factors from a model we developed and tested to predict adherence such as perceptions of treatment effectiveness, side effects of medications, current support of significant others, and risks and benefits from alcohol use. The Check-In information will be used by ACHESS for triage and feedback. The Care Manager will receive a summary report of Check-In data whenever they wish as well as the day before a scheduled appointment and whenever a patient reports a lapse or desire to re-enter treatment. Relative to Marlatt’s model, the Check-In represents ongoing self monitoring and behavior assessment to help a person be aware of urges, and will inform ACHESS on which services might benefit them the most and when they should be delivered.

Set-up and Updates

Before using the system on a daily basis, patients will, with the assistance of a counselor who will become their care manager, enter set-up information that will be used to tailor ACHESS to their own specific needs and preferences. Although the information gathered at set-up will do much to inform the initial tailoring of services, ACHESS will be regularly updated to address the changing recovery needs of each individual user. Care managers will be sent user data reports and mini-assessments data, which they can use to supplement communications with patients as they work together to determine any appropriate changes that should be made to the initial ACHESS set-up. The patient and the care manager will review which ACHESS service are working for them and which are not, and make adjustments to protocols established at set-up. Additionally, ACHESS will be programmed to automatically ‘recommend’ additional services and resources to users based on their use data.

Application of Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention Model to ACHESS

While the SDT was used as a framework to identify what the essential elements of ACHESS should be, we used Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention Model to inform the development of when each of the ACHESS services should be delivered.

We investigated how the ACHESS services align with the interventions suggested by Marlatt’s model in order to gain further insight about how the SDT-based services might be organized so that they can be delivered at the most effective time (in accordance with stage-based episodes), and to expand and refine the conceptualization of the services if needed.

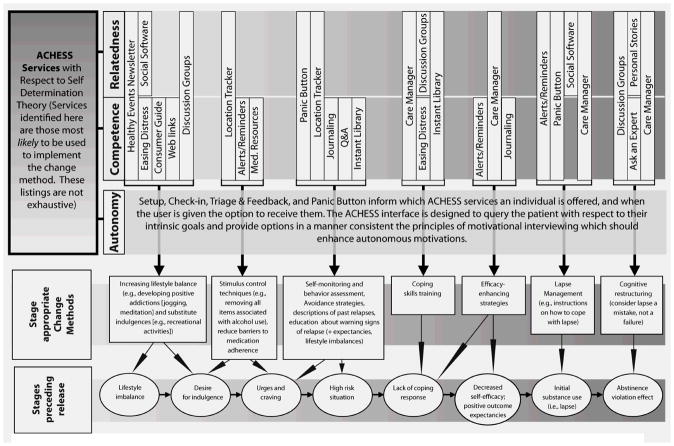

Encouragingly, we found that the models fit together quite naturally. Figure 1 shows how ACHESS fits within both Self Determination Theory (SDT) and Marlatt’s model (Larimer, Palmer, and Marlatt, 1999; Witkiewitz, Marlatt, 2004). The bottom row of boxes lists Marlatt’s stages-preceding-relapse. The row above lists the stage-appropriate-change-methods, again from Marlatt’s model. The arrows between those two rows show how the change methods could be applied to the stages preceding relapse (consistent with Marlatt’s model). The rest of Figure 1 is built around the three key elements of Self Determination Theory (autonomy, competence and relatedness).

Figure 1.

In this diagram, ACHESS services (Healthy Event Newsletter, Easting Distress,etc.) have been added according to which of the change methods that they provide or facilitate. Each of these examples of ACHESS service utilization addresses one or more of the three constructs of Self Determination Theory, as indicated by the rows Relatedness, Competence, and Autonomy. We have collapsed Rationalization and Denial into Urges and cravings, as they overlap in the context of ACHESS.

The boxes above (Health Event Newsletter, Social Software, etc.) give examples of how ACHESS services relate to SDT elements and to Marlatt’s stage appropriate change methods. In other words, for every place that an ACHESS service is listed, there is a corresponding change method and a corresponding SDT construct. The service/change method relationships are primary examples of how ACHESS addresses the interventions suggested by Marlatt’s model, but do not include all possible examples.

For example, a suggested strategy for the “high-risk situation” stage of the relapse prevention model is self monitoring and behavioral assessment. For an ACHESS user, this strategy might be executed by the location tracker service, which will monitor the user’s location via GPS and detect when he or she is near a high-risk location (e.g., favorite bar, liquor store). ACHESS can initiate avoidance strategies (e.g., suggesting a call with a member of the user’s support network). The success of such a strategy would clearly play a role in increasing the SDT construct of relatedness. So, in this case, the location tracker service is used during a high-risk situation (the when) to prevent relapse by addressing relatedness (the what).

Concerns and Goals

As mentioned previously, the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) recently provided research support to develop the technology-based prototype described in this paper and conduct a clinical trial to test its efficacy. Viewing addiction as a chronic illness or disorder, our core hypotheses focus on both harm reduction (e.g., reduction in substance abuse-related consequences, reduction in risky drinking days) and abstinence-minded outcomes (e.g., full abstinence, an increase in abstinent days). While many of the support services within ACHESS are built on an abstinence-driven ideological model of treatment, we believe the system can also be quite helpful for harm reduction and quality of life perspectives. In fact, the underlying theoretical foundation of all CHESS modules is Self Determination Theory, which has the goal of improving quality of life. ACHESS is designed to raise autonomous motivation, competence and relatedness, essential (from a Self Determination Theory perspective) to improve quality of life for people diagnoses with alcohol dependence. ACHESS is designed to warn, rescue, and prevent relapse, all of which are key elements in both abstinence and harm reduction approaches.

Additionally, we will explore several other issues that during this project. First and foremost, some may question whether patients with limited resources will be likely to use a technology-based system such as the one proposed here. Encouragingly, as reported earlier, we found evidence in our research in other health contexts that patients with the greatest needs appear to be more prolific users of technology-based education and support systems (Gustafson, Hawkins, & Boberg et al., 2002; Shaw, DuBenske & Han, et al., 2008; Shaw, Gustafson & Hawkins et al., 2006).

Readers may also question whether users of the ACHESS intervention may use smart phones for purposes such as obtaining illicit alcohols or connecting with friends who are going out to drink alcohol. Of course, mobile phones are one way in which people can engage in such activities. On the one hand, many people already have cell phones so providing them another device is unlikely to significantly impact this risk. Moreover, the phones we provide our subjects will limit the numbers they can call or receive, and the browser can restrict the web sites they can visit. While we hope this will prevent study participants from using their phones for illicit purposes, some risk will no doubt remain. We will follow this issue closely during the course of our study.

Some readers may question the ethics of offering features such a location tracking, which may be criticized as being overly intrusive into people’s live. We have asked ourselves the same question, and, in preparing this prototype, we conducted focus groups in three states with 48 people addicted to alcohol and other drugs. The majority was quite open to GPS tracking if the data were only shared with their permission - as is our intent. Indeed, using the parlance of Marlatt’s Cognitive Behavioral Relapse Prevention model (Marlatt & George, 1984), location tracking is expected to empower stimulus control techniques, making the individual in recovery aware when they are nearing a location previously identified as high risk.

Finally, even if our proposed system improves outcomes for people with alcohol dependence disorders, readers may ask themselves whether such a mobile-technology-based relapse prevention system would ever be broadly disseminated, given the ways that treatment providers are currently compensated for their services. We believe that payers will not even consider this debate until there is evidence that such systems hold the promise to cost effectively improve outcomes.

As we further explore these issues throughout the clinical trial period and beyond, it is our hope that we can develop innovative approaches to relapse prevention that allow patients to have anywhere-anytime access to evidence based, effective treatment – just by reaching into their pocket.

Acknowledgments

This research is being supported by a grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Glossary

- Self Determination Theory

-

is a theory of individual change built around the concept that change is more likely to take place if it comes from within. It has three basic elements to it:

- Relatedness is the need to experience connection to others.

- Competence is a combination of having the skills necessary to address challenges in particular behavioral domains along with a self-perception of such competence.

- Autonomy is the sense that one’s actions and experiences are volitional rather than controlled by strong external forces

- CHESS

the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System, is an umbrella term for eHealth systems developed at the University of Wisconsin to help people (patients and their informal caregivers) cope with serious illness. ACHESS refers to ‘Alcohol-CHESS’ and is the mobile-phone-based CHESS program aimed at relapse prevention for alcohol dependent people

- Coping

refers to individual behavioral and/or cognitive responses to manage stressors. ACHESS prompts people in recovery from alcohol dependence to use more active coping strategies to prevent relapse

- GPS

refers to Global Positioning System, a satellite-based technology system that can specific the location of an enabled device within a range of 15–70 feet. Most mobile phones have a GPS system included within them that allow their location to be identified

- 3G networks

refer to the ‘3rd Generation’ of currently available cellular networks that offer high data transmission speeds allowing for Internet access and real-time video

- Intrinsic motivation

refers to internal/personal factors that energize and drive goal-directed behavior. For this paper, it relates to enhancing autonomous motivation that comes from within to motivate recovery, rather than extrinsic motivation, which comes from outside (such as social pressure from friends or family or mandates from the criminal justice system)

- Motivational interviewing

in the context of alcohol treatment refers to a question-and-answer method of interviewing aimed at increasing the patient’s motivation to change, leading to abstinence or reduced levels of substance abuse

- A relapse trigger

is an experience that may stimulate cravings bringing back thoughts, feelings and memories about drug or alcohol abuse and can affect any individual in recovery who encounters people, situations, or settings associated with past substance abuse

- Recovery

for the purposes of this paper connotes a process of returning to health such that alcohol abuse and related behaviors are no longer problematic in an individual’s life as measured by harm reduction (e.g., reduction in substance abuse- related consequences, reduction in risky drinking days) and abstinence-minded outcomes (e.g., full abstinence, an increase in abstinent days)

- Smartphone

refers to a cellular telephone with built-in applications and Internet access. Smartphones provide digital voice service along with other features such as text messaging, e-mail, Web browsing, still and video cameras, calendars and media players. Smartphones have become application delivery platforms with many of the features of a mobile computer

- Tailoring

refers to any combination of information and behavior change strategies intended to reach one individual, based on characteristics unique to that person, related to the outcomes of interest, and derived from an individual assessment. Technology makes it possible to affordably personalize information for so individuals receive information that is most relevant to their situation

Contributor Information

David H. Gustafson, Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Bret R. Shaw, Email: brshaw@wisc.edu, Department of Life Sciences Communication, 316 Hiram Smith Hall, 1545 Observatory Drive, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI 53706, Tel: 608-890-1878.

Andrew Isham, Network for the Improvement of Addiction Treatment, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Timothy Baker, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Michael G. Boyle, Fayette Companies, Peoria, Illinois.

Michael Levy, CAB Health & Recovery Services, Peabody, Massachusetts.

References

- Alemi F, Stephens R, Javalghi R, Dyches H, Butts J, Ghadiri A. A randomized trial of a telecommunications network for pregnant women who use cocaine. Medical Care. 1996;34(Suppl 10):OS10–20. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199610003-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:888–918. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Ramo D, Brown S. Life stress, coping and comorbid youth: An examination of the Stress-Vulnerability Model for substance relapse. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38(3):255–262. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Kirschenbaum D. Weight control during the holidays: Highly consistent self-monitoring as a potentially useful coping. Health Psychology. 1998;17(4):367–70. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T, Piper M, McCarthy D, Majeskie M, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Hames KA, Blanco CR, Nixon SJ, Tivis LJ. Visuospatial perception, construction and memory in alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(2):136–43. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie M, Longabaugh R. General and alcohol-specific social support following treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:593–606. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Emery G. Anxiety disorders and phobias. New York: Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn I, Eunson K, Bishop S. Controlled acute and follow-up trial of cognitive therapy pharmacotherapy in outpatients with recurrent depression. British Medical Journal. 1997;171:328–334. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boberg E, Gustafson D, et al. Assessing the unmet information, support, and care delivery needs of men with prostate cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;49(3):233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Balmford J, Hunt D. The effectiveness of personally tailored computer-generated advice letters for smoking cessation. Addiction. 2004;99:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth K, Gustafson D, Hawkins R. The BARN System: Use and Impact of Adolescent Health Promotion by Computer. Computers in Human Behavior. 1994;10(4):467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Bradizza CM, Stasiewicz PR, Paas ND. Relapse to alcohol and drug use among individuals diagnosed with co-occurring mental health and substance abuse disorders: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:162–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome K, Simpson D, Joe G. The role of social support following short-term inpatient treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2002;11(1):57–65. doi: 10.1080/10550490252801648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Marlatt GA, Lichtenstein E, Wilson GT. Understanding and preventing relapse. American Psychologist. 1986;41:765–782. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess E, Brown R, Kahler C, Niaura R, Abrams DB, Goldstein MG, Miller IW. Patterns of change in depressive symptoms during smoking cessation: Who’s at risk for relapse? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:356–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capoccia V, Cotter F, Gustafson D, Cassidy EF, Ford JH, Madden L, Owens B, Farnum SO, McCarty D, Molfenter T. Making stone soup; Improvements in clinic access and retention in addiction treatment. Joint Committee Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007;2(39):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, et al. Changes in alcoholic patients’ coping responses predict 12-month treatment outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:92–100. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K. Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Polich J. Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(1):142–156. doi: 10.1037/a0014414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Humphreys K, Kypri K, van Mierlo T. Formative evaluation and three-month follow-up of an online personalized assessment feedback intervention for problem drinkers. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2006;8(2):e5. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Wild TC, Walsh GW. Interest in self-help materials in a general population sample of drinkers. Alcohols: Education, Prevention & Policy. 1999;6(2):209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Curry S, Wagne E, Grothaus L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:310–316. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JJ, McCarthy DE, Piper ME, Baker TB. Implicit and explicit alcohol motivational processes: A model of boundary conditions. In: Weirs RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2006. pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Davis JR, Glaros AG. Relapse prevention and smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R. An experimental evaluation of recovery management check-ups (RMC) for people with chronic substance abuse disorders. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;26:339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin PL, De CM, Paraherakis A, Gill K. The role of functional social support in treatment retention and outcomes among outpatient adult substance abusers. Addiction. 2002;97(3):347–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM. Assessment issues and domains in the prediction of relapse. Addiction. 1996;91:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupi P, van der Lei J. Design considerations for a personalized patient education system. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2003;95:762–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner SL. Does treatment ‘pay for itself’? Behavioral Healthcare. 2006;26(5):32–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney JW, Moos RH, Mewborn CR. Posttreatment experiences and treatment outcomes of alcoholic patients six months and two years after hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:17–29. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloria R, Angelos L, Schaefer HS, Davis JM, Majeskie M, Richmond BS, Curtin JJ, Davidson RJ, Baker TB. An fMRI investigation of the impact of withdrawal on regional brain activity during nicotine anticipation. Psychophysiology. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00823.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis MI, Funk R, Passetti L. Preliminary outcomes from the assertive continuing care experiment for adolescents discharged from residential treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;23:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Introduction to the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29(2):74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin RE, Graziano F, Chan CL. Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based information support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999a;16(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, Boberg E, McTavish F, Owens B, Wise M, Berhe H, Pingree S. CHESS: 10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2002;65:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Hawkins R, McTavish F, Pingree S, Chen W, Volrathongchai K, Stengle W, Stewart J, Serlin R. Internet-based interactive support for cancer patients: Are integrated systems better? Journal of Communication. 2008;58:238–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, McTavish F, Arora N, Mendenhall J, et al. Effects of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Stengle W, Ballard D, Hawkins R, Shaw B, et al. Use and impact of eHealth system by low-income women with breast cancer. Journal of Health Communication. 2005a;10:195–218. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Stengle W, Ballard D, Jones E, Julesberg K, McDowell H, Landucci G, Hawkins R. Reducing the digital divide for low-income women with breast cancer: A feasibility study of a population-based intervention. Journal of Health Communication. 2005b;10(Suppl 1):173–193. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Palesh T, Plsec P, Maher L, Picard R, Capoccia V. Automating addiction treatment: Enhancing the human experience and creating a fix for the future. In: Bushko R, editor. Future of intelligent and extelligent health environment. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Bosworth K, Chewning B, Hawkins R. Computer based health promotion: Combining technological advances with problem solving techniques to effect successful health behavior changes. Annals Reviews in Public Health. 1987;8:387–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.08.050187.002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Hawkins R, Boberg E, Pingree S, Serlin R, Graziano F, et al. Impact of patient centered computer-based health information and support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. Reprinted in 2000 IMIA Yearbook of Medical Informatics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, Hawkins R, Pingree S, McTavish F, Arora N, Salner J, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney C, Shiffman S, Balabanis M, Paty J. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: Prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:661–75. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood H. Report prepared by the Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 2000. Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: Estimates, update methods, and data. [Google Scholar]

- Havassy B, Hall S, Wasserman D. Social support and relapse: Commonalities among alcoholics, opiate users, and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1991;16:235–246. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Badger GJ, Rose GL, Mongeon JA, Searles JS. Decline in alcohol consumption during two years of daily reporting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:551–558. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Delaney HD. Behavioral self-control program for Windows: Results of a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:686–693. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Miller JH. Computer-based tools for diagnosis and treatment of alcohol problems. Alcohol Research & Health. 2006;29(1):36–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Squires DD, Delaney The Drinker’s Check-Up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman NG, DeHart SS, Fulerson JA. Medical care utilization as a function of recovery status following chemical addictions treatment. Journal of Addiction Disorders. 1993;12:97–108. doi: 10.1300/J069v12n01_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Najavits L. Review of empirical studies on cognitive therapy. In: Frances AJ, Hales R, editors. Review of psychiatry. Vol. 7. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1988. pp. 643–666. [Google Scholar]

- Irvin J, Bowers C, Dunn M, Wang M. Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta analytic review. Journal Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:563–570. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japuntich S, Zehner M, Smith S, Jorenby D, Valdez, Fiore M, Baker T, Gustafson D. Smoking cessation via the Internet: A randomized clinical trial of an Internet intervention for smoking cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S59–S67. doi: 10.1080/14622200601047900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett R, Basco M, Risser R, et al. Is there a role for continuation phase cognitive therapy for depressed outpatients? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;6:1036–1040. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann HK, Sobell LC. Substance Use and Misuse. Vol. 36. 2001. Natural Recovery Research Across Substance Use; p. 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski-Jannes A, Cunningham JA, Tolonen K, Bothas H. Internet-based self-assessment of drinking – 3-month follow-up data. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;32(3):533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Bull FC, Clark EM, Oswald DL. Understanding how people process health information: A comparison of tailored and untailored weight loss materials. Health Psychology. 1999;18(5):1–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Wray RJ. Tailored and targeted health communication: Strategies for enhancing information relevance. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S227–S232. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer M, Palmer R, Marlatt A. An overview of Marlatts cognitive behavioral model. Alcohol Research and Health. 1999;23(2):151–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt E, Kadden R, Cooney N, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:118–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman C, Allen J, Stout RL. Replication and extension of Marlatt’s taxonomy of relapse precipitants: Overview of procedures and results. The Relapse Research Group. Addiction. 1996;91(Suppl):51–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Conners GJ, Zyiak WH. Construct validation analyses on the Marlatt typology of relapse precipitants. Addiction. 1996;91(suppl):89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto S, Zywiak W, Connors G. Course of functioning 1 year following admission for treatment of alcohol use disorders. Journal of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(1):68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, George WH. Relapse prevention: Introduction and overview of the model. British Journal of Addiction. 1984;79(3):261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride C, Curry SJ, Stephens R, Wells EA, Roffman R, Hawkins JD. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for change in cigarette smokers, marijuana smokers and cocaine users. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 1994;8:243–250. [Google Scholar]