Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to describe the kinematic changes in children with cerebral palsy (CP) after treatments performed on the forearm, wrist or thumb, with specific attention to the changes around the trunk, shoulder and elbow kinematics.

Methods

With the use of a specific kinematic protocol, we first described the upper limb kinematics in a group of 27 hemiplegic patients during two simple daily tasks. Eight of these children were treated with botulinum toxin (Botox®, Allergan) injection or surgery and were, thereafter, evaluated with another kinematic analysis in order to compare the pre- and post-therapeutic condition. The target muscles were the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus and the adductor pollicis.

Results

Significant kinematic changes were found after treatment. Patients increased forearm supination (P < 0.05) and wrist extension (P < 0.05) during both tasks. Patients also decreased trunk flexion/extension range of motion (ROM) (P < 0.05), improved elbow ROM (P < 0.05) and improved internal shoulder rotation (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Dynamic shoulder or elbow limitations in children with mild hemiplegia involvement could be related to a compensatory movement strategy and/or co-contractions. As these proximal kinematics anomalies are improved after treatments performed at the forearm, wrist and thumb, they should not be treated first but should be reconsidered after the treatment of more distal problems.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Upper limb, Kinematic analysis, Hemiplegia

Introduction

The dynamic pattern of cerebral palsy (CP) upper limb motion is highly variable, mainly in relation to the location and the extent of the central nervous system injury. Current clinical methods of upper limb evaluation are made in terms of function, motor control, sensory impairments, dexterity, tone, degree of fixed versus dynamic deformity, and passive and active range of motion (ROM). In the higher functioning child, the quality of upper limb movement during several functional tasks is quantified using available clinical scales [1–4]. In order to better understand upper limb kinematic anomalies, several upper limb kinematic protocols have been developed and applied to small groups of children [5–8]. None of these studies has made a comparison between the pre- and post-therapeutic kinematic patterns.

The majority of treatments in children with hemiplegia are focused in order to improve the forearm supination, wrist extension and thumb position [9]. The purpose of this study is, therefore, to describe the kinematic changes after treatments performed on the forearm, wrist or thumb, with specific attention to the changes around the trunk, shoulder and elbow kinematics. With the use of a specific kinematic protocol [8], we first described the upper limb kinematics in a group of 27 hemiplegic patients during two simple daily tasks in order to define the kinematic patterns. Eight of these CP children were treated with botulinum toxin (Botox®, Allergan) injection or surgery and were, thereafter, evaluated with another kinematic analysis in order to compare the pre- and post-therapeutic condition.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study participants consisted of 12 children with no history of musculoskeletal or neurological problems (control group), representing a normative pediatric population (8 girls, 4 boys; mean age 10.3 years; range 8–14 years), and 27 children with diagnosis of hemiplegic CP (15 girls, 12 boys; mean age 13.1 years; range 8–18 years). All CP children were required to display a diagnosis of spastic hemiplegia without other motion disorders, such as dystonia. The mean birth weight was 2,884 g (range 1,500–3,900 g). In 9 cases (33%), a prenatal cerebral vascular accident was the origin of hemiplegia. Eleven percent of cases were in relation to perinatal complication. This study had ethical approval from the local ethics committee and the participants, and their guardians, gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Clinical evaluation

The 27 patients had a complete clinical upper limb evaluation in order to record the following parameters:

Sensitivity was classified into three types according to Koman et al. and Hoffer et al. [10, 11]

The children’s functional hand use according to House’s classification [12]

Muscle tone was measured on Ashworth’s scale [13]

Zancolli’s classification [14]

The active and passive ROM at the shoulder, elbow and wrist

Thumb position according to the Matev classification [15]

Experimental procedure

Subjects were asked to perform two daily tasks, named “to drink” and “to move an object”, respectively. With the subject being sat on a chair with the hips and the knees flexed at 90°, the two upper limbs were studied successively, as follows:

For the task “to drink”, the subject started from the initial position, took a cup placed at a predefined position (on a table in front of his right knee), put it to his mouth, put the cup back to its initial location and returned his/her arm to the initial position

For the task “to move an object”, the subject started from the initial position, took a cup placed on the table at the position defined above, moved it to the left to a second predefined position on the table, and then returned his/her arm to the initial position

The task “to drink” required of each child a succession of shoulder and elbow flexions and extensions and forearm pronations and supinations in order to bring the object to his/her mouth. The task “to move an object” required a succession of internal and shoulder external rotations and forearm pronations and supinations, as well as elbow and shoulder flexions and extensions in order to move the cup on the table.

For each task, the cycle was performed twice and only the second one was taken into account for the data analysis. Moreover, each task was repeated three times and the mean values were used for analysis. The height of the table and the initial and final positions of the cup on the table were normalised according to the anthropometric data of the subjects. The diameter of the cup was adapted to the dimensions of the hand and its weight was adapted to the maximal pinch force between the thumb and the index finger.

Kinematic analysis

A VICON optoelectronic system with six cameras and rigid supports provided with three markers (tripods) was used to measure the trunk, arm, forearm and hand motions (Fig. 1). Technical and anatomical frames were defined for each segment [8].

Fig. 1.

Photograph demonstrating the marker set

The following angles were obtained:

Flexion–extension, bending and axial rotation of the trunk with regard to the table

Flexion–extension, abduction–adduction and internal–external rotation of the arm with regard to the trunk, which included the motion between the scapula and the thorax, and between the humerus and the scapula

Flexion–extension and prono-supination of the forearm with regard to the humerus

Flexion–extension and radial-ulnar inclinations of the hand with regard to the forearm

Pre- and post-operative kinematic analysis

Eight of the 27 CP patients were treated with Botox® injection (n = 4) or surgery (n = 4) and, thereafter, had another complete kinematic evaluation. In patients with severe spasticity or musculotendinous contracture, surgery was centred on muscle lengthening [9, 16, 17]. Patients with mild or moderate spasticity without musculotendinous contracture were treated with Botox® injection [18, 19]. The target muscles were in the forearm or hand: pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus and adductor pollicis (Table 1). The mean time between the treatment and the second kinematic evaluation varied from 3.75 months for the Botox® injection to 16 months for surgical treatment. All of the patients had physiotherapy and occupational therapy during the post-therapeutic period. Passive stretching, improvement of the active and passive ROM around the wrist, forearm and elbow joints, and reinforcement of the antagonist muscles were performed two or three times a week during a 3-month period.

Table 1.

Summary of treatments on the eight patients

| Patient | Treatment | PT | FCR | FCU | FDS | Thumb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Botox® injection | 30 units | 30 units | Add 15 units | ||

| 2 | Surgery | Transferred | Lengthening | Lengthening FPL | ||

| 3 | Botox® injection | 30 units | 30 units | 30 units | ||

| 4 | Surgery | Transferred | Lengthening | Lengthening | ||

| 5 | Surgery | Transferred | Lengthening Add | |||

| 6 | Botox® injection | 40 units | 30 units | 60 units | Add 15 units | |

| 7 | Botox® injection | 30 units | 30 units | Add 15 units | ||

| 8 | Surgery | Transferred | Transferred to ECRB | Lengthening | Lengthening FPL |

PT pronator teres, FCR flexor carpi radialis, FCU flexor carpi ulnaris, ECRB extensor carpi radialis brevis, FDS flexor digitorum superficialis, FPL flexor pollicis longus, Add adductor pollicis

Data analysis

As the movements were carried out at different speeds from one trial to another and from one child to another, a normalisation (duration from 0 to 100%) of the curves was necessary in order to allow comparative studies.

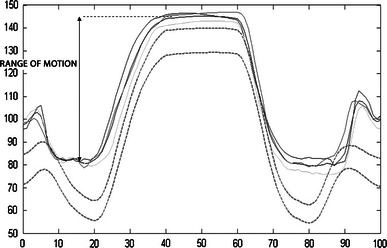

For each task and each angle, two parameters were calculated: the ROM (Fig. 2) and the mean joint angle of the whole movement. The mean and standard deviation were calculated for each parameter of each studied group. The different groups were compared using the Student t test, with a P value of less than 0.05 denoting a statistically significant difference.

Fig. 2.

Normalised curves (three trials and mean) of elbow flexion/extension range of motion (ROM) (in °) of a patient performing the task “to drink”. The dashed lines represent the healthy patients’ mean curve ±1 standard deviation (SD)

Results

Clinical evaluation

The CP group showed a mild upper limb involvement. Patients were classified between a level 4 (poor active assist) and a level 7 (spontaneous use, partial) by House’s classification system [12]. They showed a limitation in active motion mainly in forearm supination compared to the normative clinical data. Active and passive motions around the shoulder, elbow or wrist were only slightly limited (Table 2). Of the patients, 72% had a thumb-in-palm deformity, 84% were classified as Zancolli I and 16% as Zancolli II. Clinical evaluation of spasticity with Ashworth’s scale showed that forearm pronators and wrist flexors were the more spastic muscles (Table 3). The majority of patients showed spasticity (between 1 and 4 according to Ashworth’s scale) on the following muscle groups: internal shoulder rotators, forearm pronators, wrist and finger flexors.

Table 2.

Shoulder, elbow, forearm and wrist mean range of motion (ROM) of the cerebral palsy (CP) group in ° during clinical evaluation

| Mean | Max. | Min. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | Active | Abduction | 177 | 180 | 160 |

| External rotation | 56 | 90 | 10 | ||

| Passive | Abduction | 180 | 180 | 170 | |

| External rotation | 68 | 90 | 40 | ||

| Elbow | Active | Extension | −15 | 0 | −60 |

| Passive | Extension | −9 | 15 | −35 | |

| Forearm | Active | Supination | 28 | 80 | −70 |

| Passive | Supination | 64 | 90 | 0 | |

| Wrist | Passive | Extension | 70 | 80 | 20 |

| Radial incl. | 12 | 20 | 0 |

Table 3.

Mean spasticity for the CP group

| Mean Ashworth scale | Percentage of patients with clinical spasticity between 1 and 4 (Ashworth’ scale) | |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder internal rotators | 0.9 | 65 |

| Elbow flexors | 0.5 | 39 |

| Elbow extensors | 0.6 | 39 |

| Pronators | 2.2 | 88 |

| FCU | 1.4 | 83 |

| FCR | 1.4 | 78 |

| FDS | 0.9 | 66 |

FCU flexor carpi ulnaris, FCR flexor carpi radialis, FDS flexor digitorum superficialis

Kinematic evaluation

The results of the kinematic evaluation are depicted in Tables 4 and 5. For each upper limb task, the relevant minimum and maximum ROM and the mean joint angles were determined for the trunk, shoulder, elbow and wrist motion across the three planes of movement.

Table 4.

ROM and mean angle of the “to drink” task for children with CP and control children

| Angle | Range of motion | Mean angle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP (affected) | Control (dominant) | P value | CP (affected) | Control (dominant) | P value | ||

| Trunk/table | Homolateral/control at bending | 6 (3.3) | 4 (1) | 0.02* | 5 (4.7) | 1 (3) | 0.006* |

| Homolateral/control at axial rotation | 9 (3.4) | 6 (4) | 0.07 | 1 (5.5) | 0 (4) | 0.42 | |

| Flexion/extension | 15 (9.6) | 6 (2) | 0.0025* | 1 (8.2) | 9 (6) | 0.01* | |

| Arm/trunk | Flexion/extension | 48 (9.7) | 49 (11) | 0.76 | 26 (8.5) | 23 (8) | 0.16 |

| Internal/external rotation | 33 (13.4) | 23 (8) | 0.028* | 3.5 (15.7) | 15 (13) | 0.021* | |

| Abduction/adduction | 24 (11.0) | 19 (9) | 0.169 | −26 (13.2) | −13 (6) | 0.003* | |

| Forearm/arm | Elbow flexion/extension | 55 (13.4) | 79 (11) | 0.000004* | 106 (10.8) | 94 (8) | 0.001* |

| Pronation/supination | 24 (10.3) | 27 (8) | 0.33 | 133 (14.2) | 122 (10) | 0.025* | |

| Hand/forearm | Flexion/extension | 46 (14.5) | 36 (11) | 0.044* | 19 (29.3) | −22 (6) | 0.00004* |

| Radial/ulnar inclination | 16 (5.5) | 26 (7) | 0.000037* | 8 (12.6) | −1 (7) | 0.035* | |

Values are means in ° (± standard deviation [SD])

*Significant difference between cerebral palsy (CP) children and control children (P < 0.05)

Table 5.

ROM and mean angle of the “to displace” task for children with CP and control children

| Angle | Range of motion | Mean angle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP (affected) | Control (dominant) | P value | CP (affected) | Control (dominant) | P value | ||

| Trunk/table | Homolateral/control at bending | 11 (5.7) | 8 (2.8) | 0.046* | 2 (3.7) | −1 (3.5) | 0.02* |

| Homolateral/control at axial rotation | 19 (5.8) | 16.6 (5.8) | 0.169 | 8 (7.0) | 5 (3.2) | 0.27 | |

| Flexion/extension | 15 (5.8) | 9 (2.6) | 0.0013* | −2 (8.1) | 7 (5.1) | 0.001* | |

| Arm/trunk | Flexion/extension | 43 (8.9) | 43 (4.5) | 0.93 | 16 (8.5) | 11 (7.1) | 0.058 |

| Internal/external rotation | 28 (10.5) | 27 (4.2) | 0.64 | 11 (13.6) | 22 (11.7) | 0.022* | |

| Abduction/adduction | 27 (6.8) | 26 (5.5) | 0.45 | −20 (11.1) | −8 (5.9) | 0.0014* | |

| Forearm/arm | Elbow flexion/extension | 30 (8.1) | 41 (4.8) | 0.00016* | 90 (11.4) | 74 (8.4) | 0.0008* |

| Pronation/supination | 19 (7.0) | 27 (7.9) | 0.0039* | 137 (13.2) | 124 (10) | 0.0056* | |

| Hand/forearm | Flexion/extension | 49 (18.6) | 41 (10.6) | 0.2 | 18 (20.9) | −20 (6.9) | 0.00004* |

| Radial/ulnar inclination | 16 (5.1) | 28 (5.4) | 0.0000023* | 6 (9.8) | −1 (7.2) | 0.05* | |

Values are means in ° (± standard deviation [SD])

*Significant difference between cerebral palsy (CP) children and control children (P < 0.05)

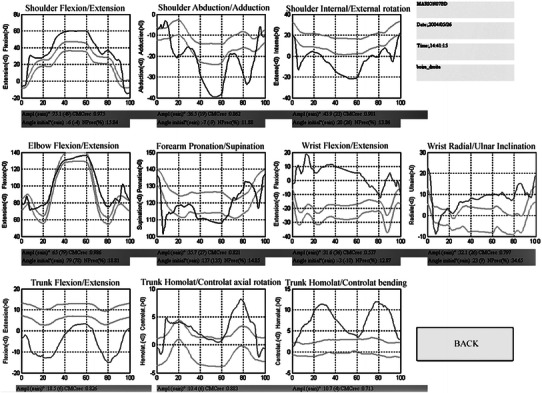

In summary, children with hemiplegia performed both tasks with significantly increased shoulder abduction and external rotation position, an increased elbow flexion, forearm pronation and wrist ulnar deviation position, and the trunk in homolateral bending and extension. The ROM was increased in trunk bending and trunk flexion/extension, and was decreased in elbow flexion/extension, forearm pronation/supination and wrist radial/ulnar deviation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kinematic graphs of the trunk, shoulder, elbow and wrist motion of a hemiplegic patient performing the task “to displace”

Pre- and post-operative kinematic analysis

Significant kinematic changes were found after treatment was performed on the forearm, wrist or thumb (Table 6). Patients increased forearm supination (P < 0.05) and wrist extension (P < 0.05) during both tasks.

Table 6.

Significant ROM and mean angle changes between the pre- and post-therapeutic condition

| Angle | Pre-operative | Post-operative | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trunk/table | Homolateral/control at bending | 11 | 9 | 0.08 |

| Homolateral/control at axial rotation | 24 | 20 | 0.02* | |

| Flexion/extension | 17 | 12 | 0.001* | |

| Arm/trunk | Flexion/extension | 13 | 15 | 0.42 |

| Internal/external rotation | 2 | 13 | 0.005* | |

| Abduction/adduction | −20 | −22 | 0.62 | |

| Forearm/arm | Elbow flexion/extension | 54 | 61 | 0.01* |

| Pronation/supination | 145 | 125 | 0.02* | |

| Hand/forearm | Flexion/extension | 35 | 7 | 0.02* |

| Radial/ulnar inclination | 0 | 4 | 0.47 |

Values are means in °

*Significant difference between pre- and post-operative (P < 0.05)

Other significant kinematic changes were found at the level of the trunk, shoulder and elbow:

Decreased trunk flexion/extension and axial rotation ROM (P < 0.05)

Improved elbow ROM (P < 0.05) during both tasks

Improved internal shoulder rotation (P < 0.05) during the task “to move an object”

Discussion

Upper limb evaluation in children with cerebral palsy

Several upper limb clinical assessment methods have been used in order to define prognosis or to evaluate the results after treatment [12, 14, 20–24]. We adopted recommendations from the International Society of Biomechanics [25] and from other authors [5, 26]. The commonly performed tasks found in the literature were reaching or pointing tasks [22], hand-to-mouth, also called the “cookie test” [5, 6], and hand-to-head tasks [6, 27]. For our study, we chose to perform a hand-to-mouth test like other authors and another original one, which consisted of moving a cup on a table. We think that these two tasks are complementary, easy, daily tasks for children. Indeed, the first task mainly induces movements of the limb in the sagittal plane, while the second mainly induces movements in the coronal and horizontal planes.

There were many significant kinematic differences between the hemiplegic group and the control group in the ROM and joint position during the two tasks described. Some of these differences are related to muscle spasticity or retraction: the forearm position in pronation and the wrist in flexion and ulnar deviation are related to the primary involvement of the forearm pronators and wrist flexors muscles. However, proximal kinematic differences around the trunk, shoulder or elbow cannot be explained only by spasticity. Two explanations could, then, be suggested for these differences between the CP children and the control group:

One explanation could be that, in order to compensate for the lack of available ROM of the distal joints (the forearm and the wrist), additional degrees of freedom are integrated in the movement strategy in the proximal joints (the shoulder and the elbow) to perform the tasks as described in an adult hemiplegic population [28, 29].

The other explanation could be related to muscle hyperactivity, as the subjects encountered difficulties in opening the hand to take the cup, extending the wrist or to supinating the forearm to perform the tasks.

The linking of specific associated movements to a single joint deformity implies that treatment aiming at the correction of that single impairment will have an effect on all degrees of freedom involved in these associated movements [7]. The differentiations between a true impairment and a compensatory movement are, then, essential for the planning of treatment for multiple dynamic deformities. Associated compensatory movements should not be mistaken for separate impairments, as they do not need treatment. Therefore, the post-therapeutic evaluation is essential.

Wrist and forearm kinematics

Patients performed both tasks with the forearm in pronation and the wrist in ulnar deviation. These abnormal joint dynamic positions can be explained by the primary involvement of the wrist flexors and the pronator muscles. By the direct action of botulinum toxin or surgery on the wrist flexors and on the pronator teres muscles, patients improved forearm supination (P < 0.05) and wrist extension (P < 0.05) during both tasks after treatment.

Elbow kinematics

In the group of patients, the kinematic evaluation showed that the ROM of elbow flexion/extension was significantly decreased with an increased elbow flexion position. However, the clinical evaluation of spasticity showed that the elbow flexors were the less spastic muscles (Table 4) and active or passive ROM of elbow flexion/extension showed few limitations, with a mean lack of active elbow extension of only 15° (Table 2). This dynamic elbow flexion position could, then, have two origins:

The Steindler effect related to the involvement of the pronator and wrist flexor muscles.

A dynamic hyperactivity of the biceps and/or brachio-radialis muscles: in order to act against the pronators’ forces, the subjects use high biceps force and, consequently, a high elbow flexion movement occurs. Indeed, the biceps is a strong supinator when the elbow is flexed and the forearm in pronation.

Although no treatment was aimed at the elbow flexors, patients post-operatively improved elbow ROM during both tasks. This suggests that the pre-operative dynamic elbow limitation was more related to an elbow flexor hyperactivity rather than spasticity or retraction. A synchronic dynamic electromyography (EMG) was performed during this study and the results will be the subject of a future publication. These findings have therapeutic consequences: a dynamic pre-operative elbow flexion position and a decreased active elbow ROM should not be treated first but should be reconsidered after the treatment of more distal problems.

Trunk and shoulder kinematics

With the elbow locked in flexion, compensatory trunk movements in flexion and extension are used in order to reach the object and to perform the tasks [24].

Kinematic evaluation showed that the shoulder was mainly in external rotation and abduction during the two tasks described. The pre-operative excess of shoulder external rotation and trunk bending can be interpreted as a compensatory motor strategy: with the forearm in a pronation position, homolateral trunk bending and shoulder external rotation could contribute to produce an “extrinsic forearm supination” [7].

There was an improvement in trunk and shoulder position after treatment. This confirms that limitations around the hand, wrist and forearm are compensated by additional degrees of freedom around the shoulder and trunk, as these proximal elbow kinematic anomalies improved after the treatment of distal elbow problems. Dynamic anomalies around the shoulder should, then, be reconsidered after the treatment of more distal problems.

Limitations of the study

The CP group with a kinematic evaluation is the largest described in the literature to our knowledge, but the number of patients treated is small and should be increased in future studies.

Another drawback is the use of two different treatments, surgery or Botox® injection. However, the purpose of our study was not aimed at the kinematic results after a specific treatment or to compare different treatments: the goal of this study was to describe the compensations around the shoulder or elbow and to describe the changes of motor strategies after treatments on the forearm, wrist and thumb.

Conclusion

Upper limb kinematic evaluation in a group of children with mild hemiplegia involvement showed significant differences when compared to a control group. Children with hemiplegia performed both of the tasks with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation, the elbow in flexion, the forearm in pronation, the wrist in ulnar deviation and the trunk in homolateral bending and extension.

Limitation of forearm supination related to pronator spasticity/retraction involves:

Increased biceps activity in order to improve the forearm supination. The elbow then becomes flexed with a trunk compensation with increased flexion/extension movements.

Some compensatory movements with “extrinsic forearm supination” with an increased shoulder external rotation and homolateral trunk bending.

Dynamic shoulder or elbow limitations in children with mild hemiplegia involvement could be related to a compensatory movement strategy. These proximal anomalies should not be treated first but should be reconsidered after the treatment of distal problems around the forearm, wrist and thumb.

References

- 1.Randall M, Carlin JB, Chondros P, Reddihough D. Reliability of the Melbourne assessment of unilateral upper limb function. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:761–767. doi: 10.1017/S0012162201001396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davids JR, Peace LC, Wagner LV, Gidewall MA, Blackhurst DW, Roberson WM. Validation of the Shriners Hospital for Children Upper Extremity Evaluation (SHUEE) for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2006;88(2):326–333. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor N, Sand PL, Jebsen RH. Evaluation of hand function in children. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1973;54:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Holmefur M, Kottorp A, Eliasson AC. The assisting hand assessment: Current evidence of validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rau G, Disselhorst-Klug C, Schmidt R. Movement biomechanics goes upwards: from the leg to the arm. J Biomech. 2000;33:1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(00)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackey AH, Walt SE, Lobb GA, Stott NS. Reliability of upper and lower limb three-dimensional kinematics in children with hemiplegia. Gait Posture. 2005;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreulen M, Smeulders MJC, Veeger HEJ, Hage JJ. Movement patterns of the upper extremity and trunk associated with impaired forearm rotation in patients with hemiplegic cerebral palsy compared to healthy controls. Gait Posture. 2007;25(3):485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitoussi F, Diop A, Maurel N, Laassel el M, Penneçot GF. Kinematic analysis of the upper limb: a useful tool for children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15(4):247–256. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Heest AE, House JH, Cariello C. Upper extremity surgical treatment of cerebral palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24:323–330. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koman LA, Gelberman RH, Toby EB, Poehling GG. Cerebral palsy. Management of the upper extremity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;253:62–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffer MM, Perry J, Melkonian GJ. Dynamic electromyography and decision-making for surgery in the upper extremity of patients with cerebral palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 1979;4:424–431. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(79)80036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.House JH, Gwathmey FW, Fidler MO. A dynamic approach to thumb-in-palm deformity in cerebral palsy. Evaluation and results in fifty-six patients. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1981;63:216–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashworth B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodol in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner. 1964;192:540–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zancolli EA, Zancolli ER., Jr Surgical management of the hemiplegic spastic hand in cerebral palsy. Surg Clin N Am. 1981;61:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)42389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matev I. Surgery of the spastic thumb-in-palm deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(91)90068-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gschwind C, Tonkin M. Surgery for cerebral palsy: Part 1. Classification and operative procedures for pronation deformity. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:391–395. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(05)80260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonkin M, Gschwind C. Surgery for cerebral palsy: Part 2. Flexion deformity of the wrist and fingers. J Hand Surg Br. 1992;17:396–400. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(05)80261-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Autti-Rämö I, Larsen A, Peltonen J, Taimo A, Von Wendt L. Botulinum toxin injection as an adjunct when planning hand surgery in children with spastic hemiplegia. Neuropediatrics. 2000;31:4–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-15289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corry IS, Cosgrove AP, Walsh EG, McClean D, Graham HK. Botulinum toxin A in the hemiplegic upper limb: a double-blind trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green WT, Banks HH. Flexor carpi ulnaris transplant and its use in cerebral palsy. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1962;44:1343–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samilson RL, Morris JM. Surgical improvement of the cerebral-palsied upper limb. Electromyographic studies and results of 128 operations. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1964;46:1203–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourke-Taylor H. Melbourne Assessment of Unilateral Upper Limb Function: construct validity and correlation with the Pediatric Evaluation of Disability Inventory. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:92–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2003.tb00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desloovere K, Molenaers G, Feys H, Huenaerts C, Callewaert B, Van de Walle P. Do dynamic and static clinical measurements correlate with gait analysis parameters in children with cerebral palsy? Gait Posture. 2006;24(3):302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaspers E, Desloovere K, Bruyninckx H, Molenaers G, Klingels K, Feys H. Review of quantitative measurements of upper limb movements in hemiplegic cerebral palsy. Gait Posture. 2009;30:395–404. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2009.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu G, van der Helm FC, Veeger HE, Makhsous M, Van Roy P, Anglin C, Nagels J, Karduna AR, McQuade K, Wang X, Werner FW, Buchholz B, International Society of Biomechanics ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion—Part II: shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J Biomech. 2005;38(5):981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senk M, Chèze L. Rotation sequence as an important factor in shoulder kinematics. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21:S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rab G, Petuskey K, Bagley A. A method for determination of upper extremity kinematics. Gait Posture. 2002;15:113–119. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(01)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cirstea MC, Levin MF. Compensatory strategies for reaching in stroke. Brain. 2000;123:940–953. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin MF, Michaelsen SM, Cirstea CM, Roby-Brami A. Use of the trunk for reaching targets placed within and beyond the reach in adult hemiparesis. Exp Brain Res. 2002;143(2):171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00221-001-0976-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]