Abstract

It has been demonstrated that exogenous expression of a combination of transcription factors can reprogram differentiated cells such as fibroblasts and keratinocytes into what have been termed induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. These iPS cells are capable of differentiating into all the tissue lineages when placed in the right environment and, in the case of mouse cells, can generate chimeric mice and be transmitted through the germline. Safer and more efficient methods of reprogramming are rapidly being developed. Clearly, iPS cells present a number of exciting possibilities, including disease modeling and therapy. A major question is whether the nuclei of iPS cells are truly rejuvenated or whether they might retain some of the marks of aging from the cells from which they were derived. One measure of cellular aging is the telomere. In this regard, recent studies have demonstrated that telomeres in iPS cells may be rejuvenated. They are not only elongated by reactivated telomerase but they are also epigenetically modified to be similar but not identical to embryonic stem cells. Upon differentiation, the derivative cells turn down telomerase, the telomeres begin to shorten again, and the telomeres and the genome are returned to an epigenetic state that is similar to normal differentiated somatic cells. While these preliminary telomere findings are promising, the overall genomic integrity of reprogrammed cells may still be problematic and further studies are needed to examine the safety and feasibility of using iPS cells in regenerative medicine applications.

Keywords: telomere, telomerase, iPS, pluripotent, stem cell

Reprogramming the Nucleus

The idea that somatic cells can be reprogrammed into pluripotent cells has been around for many years and is supported by a variety of observations and studies. Early cell fusion experiments between somatic cells and embryonic stem cells demonstrated that differentiation is reversible and that epigenetic marks in nuclei can be reprogrammed [1]. Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) into oocytes and the cloning of entirely new animals from a single cell, first with frogs, and then with sheep (Dolly), mice, and cattle, showed conclusively that it was possible to reprogram a somatic nucleus to create a completely pluripotent cell [2]. Immediate questions arose from the SCNT studies as to whether the cloned animals were normal. In other words, did the cloning process completely “rejuvenate” the nuclei or were there remnants of epigenetic and genetic changes that could not be wiped away by SCNT? One measure of genomic integrity is the length of telomeres. It was speculated that cloning from adult somatic cells might result in organisms that inherited telomeres that were similar to or shorter than the telomeres of the cells from which they were cloned. Indeed, the analysis of Dolly’s telomeres indicated that they were shorter than age-matched controls [3]. This observation was given further support by analysis of other cloned sheep which also exhibited shorter telomeres than normal [4]. This finding dampened excitement in the cloning field and suggested that cloned animals may suffer from premature aging due to shortened telomeres. However, subsequent studies on cloned cattle did not reach the same conclusion; the cloned cattle had telomeres that were similar in length to age-matched normal controls [5]. More recent studies have shown that telomeres are elongated during the cloning process, most likely due to the fact that telomerase is reactivated in embryos in the blastocyst stage (in both normal and cloned nuclei) [6]. The reasons for the earlier results with sheep are still not completely clear. Thus, it would appear that although cloning might result in other genetic problems, elongation of telomeres to a normal length does not necessarily appear to be one of them.

Transfer of a somatic cell nucleus to an oocyte followed by stimulation to divide (i.e. SCNT) is associated with complete reprogramming of the nucleus but how this process is initiated and implemented is still unknown. Embryonic stem (ES) cells, which have the capacity to generate chimeric animals when injected into blastocysts, were viewed as a potential starting point to determine what factors might be necessary for pluripotency. The careful study of what genes were specifically expressed in ES cells pointed to transcription factors that might be involved in initiating and maintaining the pluripotent state [7]. It was reasoned that only a few transcription factors might trigger a cascade of events to reprogram a cell. Several of these transcription factors, including Oct3/4, Sox2, and Nanog were found to be essential for maintenance of pluripotency in ES cells [8–9]. Thus, these findings provided a basis for studies to determine what factors might completely reprogram a somatic cell nucleus.

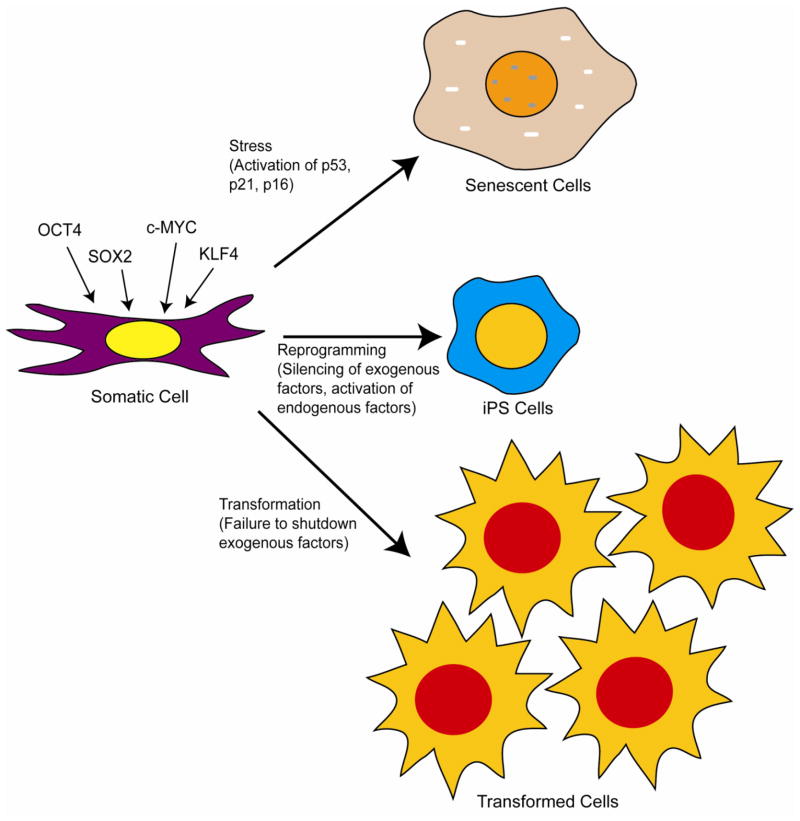

A seminal breakthrough came when Yamanaka’s group determined that exogenous expression of only four transcription factors (i.e. Oct4, c-Myc, Klf4, and Sox 2) reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts to pluripotency, albeit inefficiently (figure 1) [10]. One must consider this an extraordinary feat given the fact that so many things could have gone wrong and that so many gene combinations simply would not work. In these studies, pluripotency was tested by the ability of the cells to differentiate into various lineages in culture and to form teratomas (and all tissue lineages) in mice [10]. Initial experiments indicated that the reprogrammed cells or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, as they became to be known, failed to form adult chimeric mice. However, it was later demonstrated in subsequent studies that utilization of different markers for pluripotency resulted in iPS cells that could form chimeras and be transmitted through the germline [11–13]. Generally, expression of the four transcription factors, c-Myc, Klf4, Oct4, and Sox2 result in reprogramming of somatic cells to iPS cells, albeit at very low frequencies that vary with the age of the cells and the tissue of origin [10–12, 14–15]. Other combinations that include Nanog and Lin28 have also been found to work [16]. Surprisingly, reprogramming of somatic cells, although inefficient, has proven to not be extraordinarily difficult and has been repeated by a large number of laboratories. In most cases, the expression of the exogenous reprogramming factors is achieved through the use of lentiviral mediated gene transduction (using replication defective vectors). Because of concerns over the safety of using integrating retroviruses, other non-viral based methods have been developed (see later discussion) [17]. It should be noted that true induction of pluripotency requires that the introduced genes are expressed only temporarily and then must be shut down through cell-mediated transcriptional repression. In other words, the exogenous transcription factors initiate a cascade of events that lead to upregulation of endogenous transcription factors (including NANOG and some of the same genes that were expressed exogenously) and pluripotency (figure 1). If the exogenous genes continue to be expressed, it can lead to reduced iPS cell quality and transformation [13]. The latter is really not an unexpected finding, given that some of the exogenously expressed gene (e.g. c-myc) can act as oncogenes.

Figure 1.

Derivation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells and possible outcomes of exogenous expression of reprogramming factors. The four transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, C-MYC, and KLF4 can reprogram somatic cells (e.g. fibroblasts and keratinocytes) to pluripotency but only if initial expression of the exogenous transgenes are shut down and endogenous factors are activated. If the exogenous factors are not shut down or endogenous factors are aberrantly activated, malignant transformation can occur. Exogenous expression of the four factors can also result in stress mediated senescence mediated by p53, p21WAF, and p16INK4a.

In addition to the problem of transformation associated with reprogramming, many cells that are transduced with the transcription factors fail to divide and succumb to either senescence or apoptosis [18]. Early studies demonstrated that expression of SV40 large T antigen increased the efficiency of reprogramming of human cells, indicating a role for the p53 and pRb pathways in blocking efficient production of iPS cells [14]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that p53, p21WAF/CIP, and p16INK4a act as barriers to the generation of iPSCs through induction of stress-activated senescence [19–22]. Knocking these genes out (mouse) or knocking them down (human) increased the efficiency of reprogramming. It was concluded that reprogramming may make cells particularly susceptible to stress and that this results in activation of the stress response pathways (i.e. p53 and pRb pathways), leading to senescence or apoptosis (figure 1)[18]. Thus, strategies to transiently downregulate these pathways might allow more efficient iPS reprogramming. However, it should be noted that such a strategy is likely to allow generation of iPS cells that have genetic damage.

Telomerase and Telomeres in iPS cells

Telomere Elongation in iPS Cells

As with SCNT, there are questions regarding the roles of telomerase and telomere elongation in iPS reprogramming. Initial studies indicated that exogenous expression of TERT, the reverse transcriptase component of telomerase, with the various mixes of reprogramming transcription factors increased the efficiency of iPS reprogramming [14]. Using somatic cells from telomerase null mice, it was demonstrated that cells from later generations, which have very short telomeres, could not be reprogrammed, most likely because of the genetic instability resulting from telomere fusions [23]. Reintroduction of telomerase restored the efficiency of iPS cell generation to that of wild-type. It has been demonstrated that iPS cells derived from wild-type mice and normal human cells exhibit progressively longer telomeres with passaging, indicating that most telomere elongation occurs post-programming as long as the iPS stage is maintained [23–26]. Interestingly, telomere elongation occurs similarly between iPS cells derived from both young and old individuals (mice and humans), indicating that the telomeres of aged cells can be restored to a length that is on par with ES cells [23, 26].

Telomere Chromatin in iPS Cells

In addition to length, telomere chromatin is altered during the reprogramming process. In somatic cells, telomere regions have higher levels of trimethylation of histone H3 at Lysine 9 (H3K9) and histone H4 at lysine 20 (H4K20) as compared to the rest of the genome [27]. Upon reprogramming, the telomere regions exhibit lower levels of trimethylation at these histone sites, similar to what has been observed in ES cells [23]. Methylation of the subtelomeric DNA itself may also be altered upon reprogramming. In human iPS cells, subtelomeric regions were found to be hypermethylated as compared to the cells from which they were derived, although significant heterogeneity in methylation patterns were observed [24]. However, no obvious changes in levels of DNA methylation in subtelomeric regions were observed upon reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts [23]. The reason for these differing results is unknown. As another measure of chromatin remodeling at the telomere, it was demonstrated that both mouse and human iPS cells exhibit an increased abundance of telomere-specific UUAGGG-rich RNAs (TelRNAs or TERRAs) [23–24]. TERRAs are known to regulate telomere length and are believed to be involved in establishment of chromatin structure at the telomere [28]. The association of TERRAs with telomere binding proteins, histone HP1α, trimethylated H3K9, and subunits of the origin replication complex implicate a role in telomere heterochromatin formation, possibly by stabilizing these interactions [29]. While it has been demonstrated that levels of TERRA go up during reprogramming, significant heterogeneity in levels was observed between clones of human iPS cells [24]. In mouse iPS cells, TERRA transcript levels were upregulated but did not reach levels observed in mouse ES cells [23]. Thus, while a number of questions still remain, these results would suggest that reprogramming modifies the chromatin state of cells to make them similar but not identical to that found in ES cells. However, the telomere chromatin reverts back to a state more similar to the cells from which they were derived when iPS cells are forced to differentiate into various lineages.

It should be noted here that genome-wide methylation patterns have been found to be different between iPS and ES cells, indicating that the reprogrammed epigenetic state in iPS cells is not identical to that found in embryonic stem cells [30]. In fact, iPS cells retain certain DNA methylation patterns that are indicative of the cell type from which they were derived [31–33]. This incomplete reprogramming favors differentiation down specific lineages and may restrict others. These are important considerations if iPS cells are to be further developed for clinical use. Any aberrant chromatin formation at the telomere or elsewhere in the differentiated cells could make them dysfunctional, more prone to telomere shortening, or even susceptible to malignant transformation.

Activation of Telomerase in iPS Cells

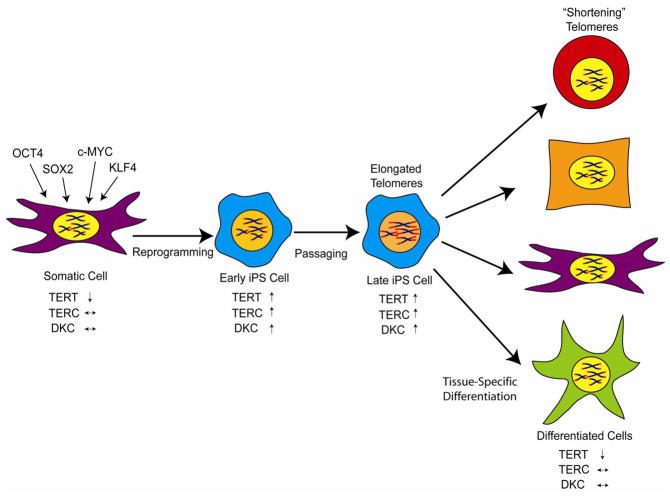

The means by which telomeres are elongated during iPS programming are beginning to be understood. Two known mechanisms of telomere elongation are through telomerase activation or through a mechanism that involves a form of mitotic recombination called ALT (alternative lengthening of telomeres). Telomere elongation by telomere recombination has been observed in early mouse embryos [34]. Therefore, the elongated telomeres observed in iPS cells could be due to mitotic recombination, telomerase activation, or a combination of these two mechanisms. Telomerase is significantly upregulated upon iPS programming (figure 2) [14–16, 23, 25, 35]. Using cells from telomerase RNA component (TERC) knockout mice (TERC−/−), successful reprogramming of fibroblasts from early generation (G1) mice was demonstrated, but reprogramming of fibroblasts from G3 mice with short telomeres was extremely inefficient, and no increase in telomere length was observed [23]. Furthermore, no evidence could be found in human iPS cells for a mechanism of telomere elongation that involved mitotic recombination mechanism (i.e. no colocalization of PML bodies with the telomere protein TRF2 and no increased telomere sister chromatid exchange) [24]. Thus, it would appear that telomere elongation during iPS programming is dependent on telomerase and not ALT. As might be anticipated, telomerase activation during iPS reprogramming is associated with upregulation of TERT, but also TERC and dyskerin become activated [25, 35]. It was demonstrated that both OCT4 and NANOG bind to the TERC and dyskerin gene regulatory elements, which may explain why these components are upregulated in iPS cells [35]. As mentioned above, extensive elongation of telomeres in iPS cells is not immediate but requires passaging in culture [24–26, 35]. One study demonstrated that TERT activation occurs in discrete steps during the reprogramming of human cells and that only those cells with the highest upregulation of telomerase restore telomeres to a length that is observed in ES cells [25]. Levels of TERT transcript and telomerase activity were found to be dramatically upregulated (>100-fold) in human iPS cells but more subtly upregulated (~2 to 3-fold) in mouse iPS cells as compared to the cells from which they were derived. These latter findings might reflect differences in telomerase regulation between humans and mice. While it is well-known that MYC upregulates TERT transcription, exogenous expression is not necessarily critical for upregulation of TERT during iPS reprogramming, since methods to reprogram cells without addition of c-Myc still result in upregulation of telomerase [23]. Differentiation of iPS into different lineages is associated with telomerase downregulation and telomere shortening (figure 2), thus indicating that telomerase activation is reversible in iPS cells much like what occurs in normal development.

Figure 2.

Telomere and telomerase dynamics during reprogramming of fibroblasts to iPS cells. Reprogramming results in activation of TERT, TERC, and dyskerin which leads to high levels of telomerase. Extensive telomere elongation requires passaging in culture. Differentiation of iPS cells down specific lineages is associated with downregulation of telomerase and shortening of telomeres.

Reprogramming Cells from Dyskeratosis Congenita Patients

In addition to studies to reprogram cells from telomerase knockout mice, experiments have also been performed to generate iPS cells from skin fibroblasts of patients with dyskeratosis congenita (DC), a disease that is caused by mutations in telomerase component or telomere binding protein genes [35–36]. In these studies, it was demonstrated that reprogramming of DC cells (with either dyskerin mutation or an autosomal dominant TERC mutation) resulted in significant upregulation of telomerase activity and concomitant maintenance or even elongation of telomeres as the cells were passaged in culture [35]. Upon differentiation of the DC-derived iPS cells, downregulation of telomerase and accelerated telomere shortening as compared to control cells was observed. These findings are partially reflective of what happens in the individuals with DC, in that they are usually disease-free in the beginning of life but then succumb to pathologies such as bone marrow failure in adolescence or early adulthood [36]. The fact that telomeres were elongated to a normal length in DC iPS cells was somewhat surprising given that the original fibroblasts had suboptimal levels of TERC. However, these results might be explained by the fact that elongation in the iPS cells occurred over time in culture. Telomere elongation, even in the presence of active telomerase, apparently takes time. There is evidence from both humans and mice that inheritance of short telomeres from a TERC heterozygous parent (TERC+/−) still results in shorter than normal telomere length in offspring even though they are wildtype for TERC [37–38]. In mice, the shorter telomeres in these wildtype mice were associated with degenerative defects and at least two generations were required for restoration to normal length [37]. These latter results would argue that reprogramming after fertilization and and embryogenesis is insufficient to bring telomere length back to normal even when there are sufficient quantities of telomerase. With regard to the DC iPS studies, there may be remaining concerns that reprogramming may not lead to truly “normal’ telomeres and further studies to address this issue are warranted.

Therapeutic Potential of iPS Cells

Overall, the above studies suggest that iPS reprogramming of normal cells results in telomerase activation and restoration of telomeres, a resetting of the clock if you will, to a length and chromatin state that is similar to that found in ES cells [27]. Importantly, upon differentiation, the cells behave like normal somatic cells in the body, exhibiting downregulation of telomerase and telomere shortening. These latter findings suggest that cells that are differentiated from iPS cells will not be readily susceptible to malignant transformation caused by aberrant telomerase activity.

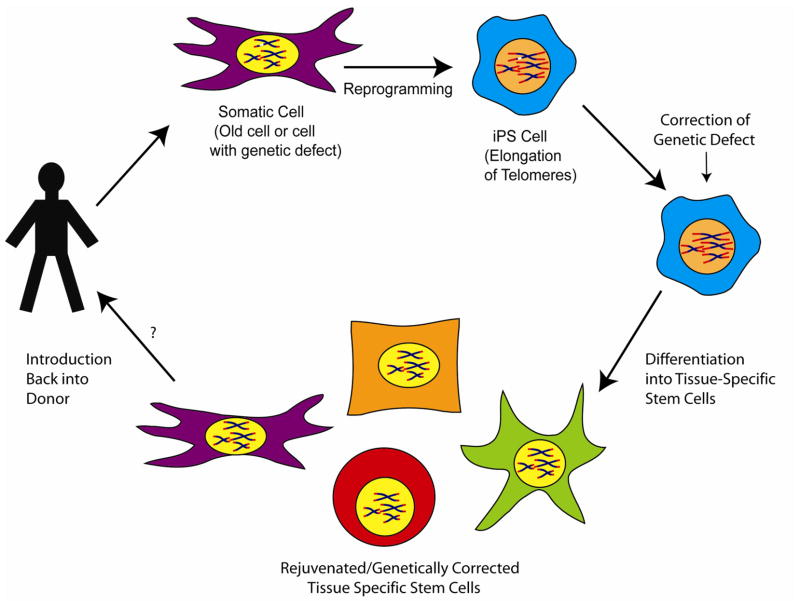

Induced pluripotent stem cells circumvent many of the ethical considerations that surround the use of ES cells. This opens up the door for a wide range of possibilities. For example, it could be possible to generate iPS cells from individuals that have genetic diseases and then repair the genetic defect through gene therapy, followed by differentiation into the proper type of tissue specific stem cell and reintroduction back into the individual to correct the defect (figure 3). One promising strategy would be to fix the genetic defect through the use of specific zinc finger endonucleases and homologous recombination [39]. Site specific recombination would decrease the likelihood of transformation and increase the likelihood that the “fixed” gene would be properly regulated.

Figure 3.

Potential uses of iPS for disease therapy. Pluripotent reprogramming of somatic cells from donors with genetic defects (white fragment on chromosome) has been demonstrated. One possibility would be to correct the genetic defect in the iPS cells, followed by differentiation into specific stem cell lineages and re-introduction back into the donor. Many questions remain as to how to safely reprogram cells, how to correct genetic defects, and how to best differentiate the cells to allow them to properly function when returned to the host.

Obstacles and Challenges

Several major obstacles still exist before the use of iPS therapy in the clinic can be realized. In particular, safety is a large concern. Most laboratories are currently using retroviral-mediated transfer of the critical transcription factors to reprogram cells. While the exogenous genes are turned off during and after reprogramming has occurred, there still exists the possibility that they could either be turned back on during differentiation or that they could integrate and aberrantly activate oncogenes. However, a variety of non-retroviral delivery techniques have recently been developed that should decrease the likelihood of the iPS cells turning into malignant cells [17]. The efficiency of reprogramming is also still an issue, and, although abrogation of senescence associated genes such as p16INK4a, p21WAF/CIP, and p53 might lead to more efficient reprogramming, it may not be wise or feasible to perform such manipulations in cells that are going to be further developed for clinical use. In addition, reprogrammed adult cells may have acquired mutations (including loss of senescence genes) that could make them more susceptible to transformation. Indeed, several recent studies demonstrated that human iPS cells exhibit significantly higher levels of chromosome copy number variations and somatic coding mutations, many of which are similar to those found in cancer cells [40-43]. The described copy number variations and mutations were apparently caused by the programming process itself [42] or pre-existed in the original cells and were likely selected for during programming [43]. These results bring up a number of concerns that reprogrammed cells would be susceptible to malignant transformation. One possible solution to this potential problem would be to genetically modify the reprogrammed cells so that they contain a suicide gene that could be activated if there was a problem with the development of malignancy. If a strategy such as this were to be tested in the clinic, it would have to be extremely efficient and effective and, so far, no sure-fire technology has been developed for this purpose.

It is also still not entirely clear how to best differentiate the reprogrammed iPS cells down the correct pathways to generate tissue specific stem cells. Some progress has been made in differentiating ES cells toward particular lineages and it is likely that these same strategies can be utilized for iPS cells. In the generation of iPS cells, there might be some value in utilizing cells other than fibroblasts as starting material for reprogramming. Other cell types could be more plastic and, in some cases, may be more likely to take on the characteristics of the desired tissue. As mentioned, recent studies indicate that cells do retain epigenetic memory and this may need to be taken into account when attempting to generate cells of certain tissue lineages [30–32]. Other cell types (e.g. keratinocytes, B-lymphocytes) have been reprogrammed and, in some cases, efficiency of reprogramming has been better than that observed for adult fibroblasts [17, 44]. With that said, however, a number of studies have described the directed differentiation of fibroblast-derived iPS cells into a variety of different cell/tissue types including insulin-secreting islet-like clusters [45], cardiomyocytes [46–48], hematopoietic cells [49–50], endothelial-like cells [51], retinal pigment epithelial cells [52–53], and neurons [54–55]. Further studies are needed to characterize these cells for regenerative capacity and safety.

Whether the reprogrammed cells would be functional in individuals with diseases caused by regenerative problems such as dyskeratosis congenita remains to be determined. As mentioned above, one of the main problems for patients with DC is bone marrow failure. A potential solution to this problem might be to first reprogram cells from these patients to iPS cells, possibly fix the genetic defect, and then differentiate them into hematopoietic stem cells. While development of true hematopoietic stem cells from iPS cell is beyond the reach of current technologies [56], even if it were possible, it is unknown if transplant of these cells back into DC individuals would be sufficient for full hematopoiesis. One has to consider the fact that the rest of the cells/tissues in DC patients also have short telomeres. For example, the so-called niche of stem cell support cells that are essential for stem cell function and proliferation might be a concern. Indeed, it has already been determined that the stem cell niche of mice with shortened telomeres is defective in supporting the function of normal hematopoietic stem cells [57]. The demonstration that DC patients can undergo successful bone marrow transplant might allay some of these concerns [58]. However, shortened telomeres in DC patients also increase their risk for developing other complications such as pulmonary fibrosis [59]. Thus, the solution is likely to be much more complicated than simply putting reprogrammed cells back into individuals.

Nevertheless, several exciting studies in mice have provided proof of principle for using iPS cells in therapy. Using a humanized model of sickle cell anemia, autologous fibroblasts were reprogrammed into iPS cells and the genetic defect corrected by homologous recombination [49]. The corrected and reprogrammed cells were then differentiated down a hematopoietic pathway by expression of HoxB4 and then used to correct the disease in mice. In another study, it was shown that iPS reprogramming of patient-derived cells from individuals with Fanconi’s anemia, which is characterized by severe genetic instability, was extremely inefficient [50]. To circumvent this problem, the cells were transduced with a wild-type FANCA gene before reprogramming. This led to more efficient reprogramming and, importantly, the resulting iPS cells and their differentiated progeny were shown to be corrected for the genetic instability phenotype in vitro. It was also recently demonstrated that iPS cells from wild-type mice could be differentiated into endothelial progenitor cells and injected into the livers of genetically defective hemophilic mice to cure their bleeding disorder [60]. Animal studies such as these will build a platform for establishing the feasibility and safety of similar approaches using human cells in patients.

iPS cells for replacement of aged tissues

The fact that functional iPS cells can be generated from somatic cells isolated from aged individuals opens up the possibility that reprogramming of “old” cells would offer potential amelioration of pathologies associated with aging. One can envision a scenario where reprogramming of somatic cells from old individuals could generate rejuvenated stem cells that could be injected into aged tissue to safely restore tissue proliferation and function. How the iPS cells would be used in the clinic is not entirely clear and will require extensive experimentation in animal models. Several questions remain. For example, would rejuvenated stem cells replace old stem cells and could this be done in an efficient enough manner to make a difference? Would the presence of “old cells” in the tissue affect the growth and functional properties of the rejuvenated cells? Another concern, as mentioned above, is that the reprogrammed cells may not be completely rejuvenated in the sense that they may contain mutations that occurred spontaneously or through oxidative damage. Further studies are needed to determine the extent of these changes if they exist.

Summary

In summary, reprogramming of differentiated somatic cells to iPS cells involves extensive alterations that include epigenetic modifications of histones and DNA as well as elongation of telomeres through the activation of telomerase. Importantly, differentiation redirects the iPS cells down a pathway where telomerase is tightly regulated, with associated telomere shortening and epigenetic alterations that return the cells to a more normal state. Thus, it would appear that somatic cell reprogramming might reset the telomere clock, although questions still remain regarding the stability and completeness of this resetting. In addition, issues of safety, efficiency of reprogramming, genomic alterations, and differentiation of iPS cells to specific cellular lineages are still concerns that need to be more thoroughly addressed. With these caveats in mind, iPS cells have significant potential for disease modeling. Further research will determine whether iPS cells may someday be useful for therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Armanios and Dana Levasseur for critical review of this manuscript. AJK and FAG are supported by NIH grant AG027388.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Blau HM, Pavlath GK, Hardeman EC, Chiu CP, Silberstein L, Webster SG, Miller SC, Webster C. Plasticity of the differentiated state. Science. 1985;230:758–766. doi: 10.1126/science.2414846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurdon JB, Melton DA. Nuclear reprogramming in cells. Science. 2008;322:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.1160810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiels PG, Kind AJ, Campbell KH, Wilmut I, Waddington D, Colman A, Schnieke AE. Analysis of telomere length in Dolly, a sheep derived by nuclear transfer. Cloning. 1999;1:119–125. doi: 10.1089/15204559950020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiels PG, Kind AJ, Campbell KH, Waddington D, Wilmut I, Colman A, Schnieke AE. Analysis of telomere lengths in cloned sheep. Nature. 1999;399:316–317. doi: 10.1038/20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanza RP, Cibelli JB, Blackwell C, Cristofalo VJ, Francis MK, Baerlocher GM, Mak J, Schertzer M, Chavez EA, Sawyer N, Lansdorp PM, West MD. Extension of cell lifespan and telomere length in animals cloned from senescent somatic cells. Science. 2000;288:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaetzlein S, Rudolph KL. Telomere length regulation during cloning, embryogenesis and ageing. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2005;17:85–96. doi: 10.1071/rd04112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Downing GJ, Battey JF., Jr Technical assessment of the first 20 years of research using mouse embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1168–1180. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, Segawa K, Murakami M, Takahashi K, Maruyama M, Maeda M, Yamanaka S. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R. Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/nbt1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiskinis E, Eggan K. Progress toward the clinical application of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:51–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI40553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banito A, Rashid ST, Acosta JC, Li S, Pereira CF, Geti I, Pinho S, Silva JC, Azuara V, Walsh M, Vallier L, Gil J. Senescence impairs successful reprogramming to pluripotent stem cells. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2134–2139. doi: 10.1101/gad.1811609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Collado M, Villasante A, Strati K, Ortega S, Canamero M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. The Ink4/Arf locus is a barrier for iPS cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1136–1139. doi: 10.1038/nature08290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53-p21 pathway. Nature. 2009;460:1132–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawamura T, Suzuki J, Wang YV, Menendez S, Morera LB, Raya A, Wahl GM, Belmonte JC. Linking the p53 tumour suppressor pathway to somatic cell reprogramming. Nature. 2009;460:1140–1144. doi: 10.1038/nature08311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marion RM, Strati K, Li H, Murga M, Blanco R, Ortega S, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Serrano M, Blasco MA. A p53-mediated DNA damage response limits reprogramming to ensure iPS cell genomic integrity. Nature. 2009;460:1149–1153. doi: 10.1038/nature08287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marion RM, Strati K, Li H, Tejera A, Schoeftner S, Ortega S, Serrano M, Blasco MA. Telomeres acquire embryonic stem cell characteristics in induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yehezkel S, Rebibo-Sabbah A, Segev Y, Tzukerman M, Shaked R, Huber I, Gepstein L, Skorecki K, Selig S. Reprogramming of telomeric regions during the generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells and subsequent differentiation into fibroblast-like derivatives. Epigenetics. 2011;6 doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathew R, Jia W, Sharma A, Zhao Y, Clarke LE, Cheng X, Wang H, Salli U, Vrana KE, Robertson GP, Zhu J, Wang S. Robust activation of the human but not mouse telomerase gene during the induction of pluripotency. FASEB J. 2010;24:2702–2715. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-148973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suhr ST, Chang EA, Rodriguez RM, Wang K, Ross PJ, Beyhan Z, Murthy S, Cibelli JB. Telomere dynamics in human cells reprogrammed to pluripotency. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marion RM, Blasco MA. Telomere rejuvenation during nuclear reprogramming. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feuerhahn S, Iglesias N, Panza A, Porro A, Lingner J. TERRA biogenesis, turnover and implications for function. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:3812–3818. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng Z, Norseen J, Wiedmer A, Riethman H, Lieberman PM. TERRA RNA binding to TRF2 facilitates heterochromatin formation and ORC recruitment at telomeres. Mol Cell. 2009;35:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, Hawkins RD, Nery JR, Hon G, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, O’Malley R, Castanon R, Klugman S, Downes M, Yu R, Stewart R, Ren B, Thomson JA, Evans RM, Ecker JR. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohi Y, Qin H, Hong C, Blouin L, Polo JM, Guo T, Qi Z, Downey SL, Manos PD, Rossi DJ, Yu J, Hebrok M, Hochedlinger K, Costello JF, Song JS, Ramalho-Santos M. Incomplete DNA methylation underlies a transcriptional memory of somatic cells in human iPS cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ncb2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, Cahan P, Kim J, Aryee MJ, Ji H, Ehrlich LI, Yabuuchi A, Takeuchi A, Cunniff KC, Hongguang H, McKinney-Freeman S, Naveiras O, Yoon TJ, Irizarry RA, Jung N, Seita J, Hanna J, Murakami P, Jaenisch R, Weissleder R, Orkin SH, Weissman IL, Feinberg AP, Daley GQ. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hewitt KJ, Shamis Y, Hayman RB, Margvelashvili M, Dong S, Carlson MW, Garlick JA. Epigenetic and phenotypic profile of fibroblasts derived from induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu L, Bailey SM, Okuka M, Munoz P, Li C, Zhou L, Wu C, Czerwiec E, Sandler L, Seyfang A, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1436–1441. doi: 10.1038/ncb1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal S, Loh YH, McLoughlin EM, Huang J, Park IH, Miller JD, Huo H, Okuka M, Dos Reis RM, Loewer S, Ng HH, Keefe DL, Goldman FD, Klingelhutz AJ, Liu L, Daley GQ. Telomere elongation in induced pluripotent stem cells from dyskeratosis congenita patients. Nature. 2010;464:292–296. doi: 10.1038/nature08792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirwan M, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita: a genetic disorder of many faces. Clin Genet. 2008;73:103–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armanios M, Alder JK, Parry EM, Karim B, Strong MA, Greider CW. Short telomeres are sufficient to cause the degenerative defects associated with aging. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:823–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldman F, Bouarich R, Kulkarni S, Freeman S, Du HY, Harrington L, Mason PJ, Londono-Vallejo A, Bessler M. The effect of TERC haploinsufficiency on the inheritance of telomere length. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17119–17124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505318102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, Pruett-Miller SM, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Chou BK, Chen G, Ye Z, Park IH, Daley GQ, Porteus MH, Joung JK, Cheng L. Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hussein SM, Batada NN, Vuoristo S, Ching RW, Autio R, Narva E, Ng S, Sourour M, Hamalainen R, Olsson C, Lundin K, Mikkola M, Trokovic R, Peitz M, Brustle O, Bazett-Jones DP, Alitalo K, Lahesmaa R, Nagy A, Otonkoski T. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laurent LC, Ulitsky I, Slavin I, Tran H, Schork A, Morey R, Lynch C, Harness JV, Lee S, Barrero MJ, Ku S, Martynova M, Semechkin R, Galat V, Gottesfeld J, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Murry C, Keirstead HS, Park HS, Schmidt U, Laslett AL, Muller FJ, Nievergelt CM, Shamir R, Loring JF. Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasi CE, Dereli-Oz A, Negrini S, Friedli M, Fragola G, Lombardo A, Van Houwe G, Naldini L, Casola S, Testa G, Trono D, Pelicci PG, Halazonetis TD. Genomic instability in induced stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:745–753. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gore A, Li Z, Fung HL, Young JE, Agarwal S, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Canto I, Giorgetti A, Israel MA, Kiskinis E, Lee JH, Loh YH, Manos PD, Montserrat N, Panopoulos AD, Ruiz S, Wilbert ML, Yu J, Kirkness EF, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Rossi DJ, Thomson JA, Eggan K, Daley GQ, Goldstein LS, Zhang K. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robbins RD, Prasain N, Maier BF, Yoder MC, Mirmira RG. Inducible pluripotent stem cells: not quite ready for prime time? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15:61–67. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283337196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tateishi K, He J, Taranova O, Liang G, D’Alessio AC, Zhang Y. Generation of insulin-secreting islet-like clusters from human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31601–31607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfannkuche K, Liang H, Hannes T, Xi J, Fatima A, Nguemo F, Matzkies M, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Pillekamp F, Halbach M, Schunkert H, Saric T, Hescheler J, Reppel M. Cardiac myocytes derived from murine reprogrammed fibroblasts: intact hormonal regulation, cardiac ion channel expression and development of contractility. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:73–86. doi: 10.1159/000227815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuzmenkin A, Liang H, Xu G, Pfannkuche K, Eichhorn H, Fatima A, Luo H, Saric T, Wernig M, Jaenisch R, Hescheler J. Functional characterization of cardiomyocytes derived from murine induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro. FASEB J. 2009;23:4168–4180. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-128546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raya A, Rodriguez-Piza I, Aran B, Consiglio A, Barri PN, Veiga A, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Generation of cardiomyocytes from new human embryonic stem cell lines derived from poor-quality blastocysts. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:127–135. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raya A, Rodriguez-Piza I, Guenechea G, Vassena R, Navarro S, Barrero MJ, Consiglio A, Castella M, Rio P, Sleep E, Gonzalez F, Tiscornia G, Garreta E, Aasen T, Veiga A, Verma IM, Surralles J, Bueren J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Disease-corrected haematopoietic progenitors from Fanconi anaemia induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2009;460:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature08129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taura D, Sone M, Homma K, Oyamada N, Takahashi K, Tamura N, Yamanaka S, Nakao K. Induction and isolation of vascular cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells--brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1100–1103. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osakada F, Jin ZB, Hirami Y, Ikeda H, Danjyo T, Watanabe K, Sasai Y, Takahashi M. In vitro differentiation of retinal cells from human pluripotent stem cells by small-molecule induction. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3169–3179. doi: 10.1242/jcs.050393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buchholz DE, Hikita ST, Rowland TJ, Friedrich AM, Hinman CR, Johnson LV, Clegg DO. Derivation of functional retinal pigmented epithelium from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2427–2434. doi: 10.1002/stem.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dimos JT, Rodolfa KT, Niakan KK, Weisenthal LM, Mitsumoto H, Chung W, Croft GF, Saphier G, Leibel R, Goland R, Wichterle H, Henderson CE, Eggan K. Induced pluripotent stem cells generated from patients with ALS can be differentiated into motor neurons. Science. 2008;321:1218–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.1158799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wernig M, Zhao JP, Pruszak J, Hedlund E, Fu D, Soldner F, Broccoli V, Constantine-Paton M, Isacson O, Jaenisch R. Neurons derived from reprogrammed fibroblasts functionally integrate into the fetal brain and improve symptoms of rats with Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5856–5861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801677105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakamoto H, Tsuji-Tamura K, Ogawa M. Hematopoiesis from pluripotent stem cell lines. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:384–391. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ju Z, Jiang H, Jaworski M, Rathinam C, Gompf A, Klein C, Trumpp A, Rudolph KL. Telomere dysfunction induces environmental alterations limiting hematopoietic stem cell function and engraftment. Nat Med. 2007 doi: 10.1038/nm1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere maintenance and human bone marrow failure. Blood. 2008;111:4446–4455. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-019729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armanios M. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:45–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu D, Alipio Z, Fink LM, Adcock DM, Yang J, Ward DC, Ma Y. Phenotypic correction of murine hemophilia A using an iPS cell-based therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:808–813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812090106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]