Abstract

Purpose

The current study examined the prevalence with which healthcare providers use a social media site account (e.g., Facebook), the extent to which they utilize social media sites in clinical practice, and their decision-making process after accessing patient information from a social media site.

Methods

Pediatric faculty and trainees from a medical school campus were provided a social media site history form and seven fictional social media site adolescent profile vignettes that depicted concerning information. Participants were instructed to rate their personal use and beliefs about social media sites and to report how they would respond if they obtained concerning information about an adolescent patient from their public social media site profile.

Results

Healthcare providers generally believed it not to be an invasion of privacy to conduct an Internet/social media site search of someone they know. A small percentage of trainees reported a personal history of conducting an Internet search (18%) or a social media site search (14%) for a patient. However, no faculty endorsed a history of conducting searches for patients. Faculty and trainees also differed in how they would respond to concerning social media site adolescent profile information.

Conclusions

The findings that trainees are conducting Internet/social media site searches of patients and that faculty and trainees differ in how they would respond to concerning profile information suggest the need for specific guidelines regarding the role of social media sites in clinical practice. Practice, policy, and training implications are discussed.

Keywords: social media site, decision-making, ethics

Social media sites (e.g., Facebook, MySpace) have become an integral part of social communication/relationships. Recent estimates suggest that approximately 55% of youth ages 12 to 17 years, 75% of adults aged 18 to 24 years, 57% of adults aged 25 to 34 years, 30% of adults aged 35 to 44 years, 19% of adults aged 45 to 54 years, 10% of adults aged 55 to 64 years, and 7% of adults aged 65 and older utilize social media sites (SMS), with usage increasing daily [1–3].

Increasing research has examined the benefits and risks of SMSs. The most obvious benefit of SMSs is that they provide the means for developing and/or maintaining relationships, regardless of physical distance [4,5]. However, some have expressed concerns regarding the privacy of the information posted on SMSs [6,7]. SMS profiles have the potential to include significant personal information with variable levels of privacy settings that allow others (e.g., friends only, networks, general public) to view information/pictures posted on their profiles [4]. This has led to concerns regarding how information posted on SMSs is utilized by others (e.g., human resources, law enforcement, and school personnel).

Healthcare Providers and Social Media Sites

Preliminary research has demonstrated that the use of SMS has already become a part of clinical practice. In a study of 302 graduate student psychotherapists, 27% of students reported seeking information about a patient from the Internet out of curiosity, to establish the truth, and/or to gather more information [8]. However, little is known about how patient information obtained from the Internet is utilized in clinical practices, the potential consequences of obtaining such information, or if training faculty also conduct similar searches.

The decision to access patient information through an Internet/SMS search represents a unique dilemma that may affect treatment or the healthcare provider-patient relationship. Adolescents and providers may have different perceptions about the extent that SMS profile information represents public versus private information as providers traditionally only gather information with the informed consent to do so. While posted SMS profile information with no privacy settings represents public information from a legal standpoint [9], the adolescent may not have intended for the healthcare provider to be the recipient of such information or the potential consequences of posted information [10,11].

Once healthcare providers seek patient SMS information, they are then charged with how to best respond. Responses become even more critical if a patient posts information that could affect the patient’s physical and/or emotional health. For example, research has supported that some adolescents post evidence of high risk behaviors including alcohol consumption, tobacco use, marijuana use, suicidal ideation, cyberbullying, and cyberstalking on their SMS profiles [12]. If providers access posted SMS information indicating that their adolescent patient has been harmed (e.g., physically abused, intimate partner violence); is at risk for self-harm (e.g., suicidal ideation); or is threatening to harm others, then the provider may be ethically or legally obligated to respond [13–19]. In this sense, it is possible that the provider may assist in protecting the patient/others from harm.

However, clinical responses are complicated by the fact that more than half of adolescents admit to posting false information on their SMS profiles, leading to questions about the validity of the information obtained [2,20]. Given the questionable validity of SMS posts, providers risk several consequences in choosing to respond to concerning information. Adolescents may view the providers’ SMS search as an invasion of privacy, which could disrupt or even end their relationship. If the healthcare provider chooses not to act due to uncertainty about the validity of information and the adolescent experiences subsequent harm, the provider may be liable for not attempting to protect their patient from harm [19]. However, if the provider acts upon inaccurate information which results in undue harm, they also may be liable [21].

The Current Study

Overall, the decision to conduct a SMS search for a patient may ultimately create a significant healthcare provider-patient dilemma. Therefore, the current study represents an important step in understanding the prevalence and clinical decision-making process behind healthcare providers’ utilization of SMSs within practice. In light of the increasing popularity of SMSs, evidence that providers are seeking patient information from the Internet, and the possible concerning situations that may arise, the intersection between adolescents’ SMS use and clinical practices needs to be further explored and understood. Currently, there are no professional guidelines that address what factors healthcare providers should consider in deciding to access and respond to concerning adolescent patient information obtained from an Internet/SMS search. Further, a generational gap in technology immersion likely exists between faculty and their trainees, which may result in faculty not being prepared to adequately provide guidance to their trainees about SMS use in clinical practice. Given their different scopes of practice and training, medical and behavioral health providers may vary in their responses to accessed SMS information.

Therefore, the current study aimed to answer the following questions: 1.) How prevalent is the use of SMSs by healthcare providers? 2.) To what extent do healthcare providers view conducting Internet or SMS searches for people they know as an invasion of privacy? 3.) How prevalent is the practice of conducting SMS searches for patients? 4.) Do differences exist between how faculty and their trainees respond to adolescent patient information posted on fictional SMS profiles? 5.) How do providers from behavioral health and medical disciplines respond to patient SMS information? 6.) What drives the clinical decision-making process about how to best respond when healthcare providers are presented with concerning information obtained from fictional adolescent patient SMS profiles?

METHODS

Participants

All pediatric medical and behavioral health faculty (i.e., pediatricians, psychologists, clinical social workers) and their respective trainees (e.g., residents, interns, practicum students) at a medical school in South Florida were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria included any pediatric faculty or trainee who provides outpatient services. Both medical and behavioral health providers were selected to participate in this study because they consistently work collaboratively on interdisciplinary teams when providing evaluation and intervention services to patients. This study was conducted in accordance with a public hospital and university-based Institutional Review Board. All respondents who completed the study were compensated $10. Of 128 eligible personnel invited to participate, 109 participants completed the study, resulting in a participation rate of 85%. Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total count n |

Weighted % (N = 109) |

Faculty % (n = 29) |

Trainee % (n = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 22 | 20.18 | 27.59 | 17.50 |

| Female | 87 | 79.82 | 72.41 | 82.50 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 years | 13 | 11.93 | 0.00 | 16.25 |

| 25–34 years | 71 | 65.14 | 31.03 | 77.50 |

| 35–44 years | 14 | 12.85 | 37.93 | 3.75 |

| 45–54 years | 7 | 6.42 | 20.69 | 1.25 |

| 55–64 years | 2 | 1.83 | 6.90 | 0.00 |

| 65+ years | 2 | 1.83 | 3.45 | 1.25 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 50 | 45.87 | 51.72 | 43.75 |

| Black or African American | 14 | 12.85 | 10.34 | 13.75 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 34 | 31.19 | 27.59 | 32.50 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6 | 5.50 | 6.90 | 5.00 |

| Other | 5 | 4.59 | 3.45 | 5.00 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Behavioral health provider | 68 | 62.39 | 58.62 | 63.75 |

| Medical health provider | 41 | 37.61 | 41.38 | 36.25 |

Measures

Demographic form

Demographic information was collected on participants, including gender, age, race, discipline, and professional/trainee status.

Social media site history form

A 9-item questionnaire was designed to measure participants’ frequency of SMS use; beliefs about searching for people on the Internet/SMSs; and history of conducting Internet/SMS searches for patients.

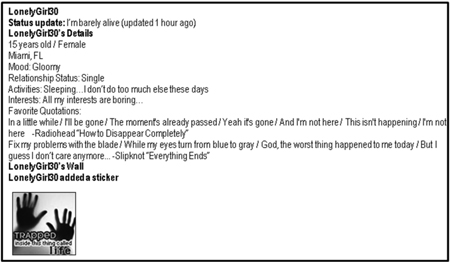

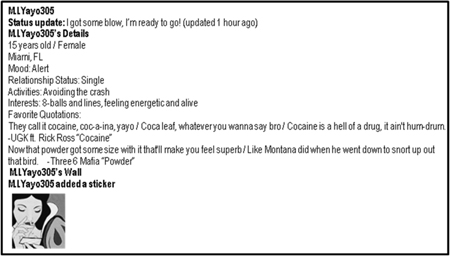

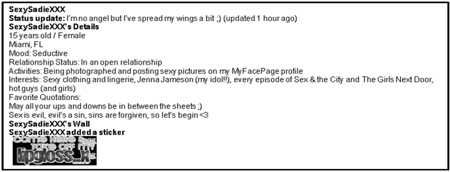

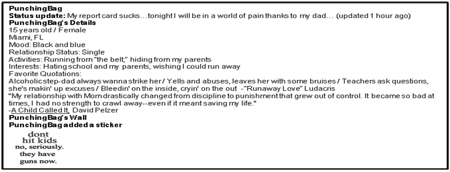

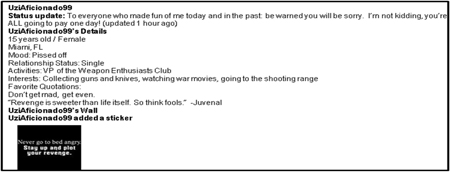

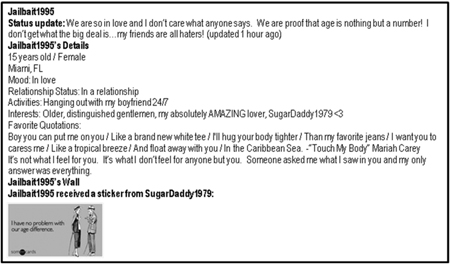

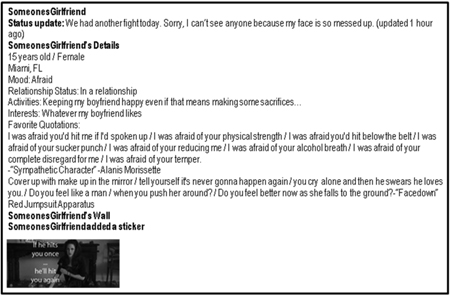

Social media site fictional profiles

Nine initial fictional SMS profiles and twelve rationales for decision-making were developed through a multidisciplinary consensus panel to assess how providers would respond if they accessed a patient’s information from a fictional SMS (i.e., MyFacePage). The vignettes and rationales were piloted on 21 medical and behavioral health providers and trainees. Pilot participants also provided qualitative feedback. Pilot vignettes that resulted in the most variable decisions (<50% agreement) and decision rationales selected by at least 10% of participants across vignettes were maintained. Two profile vignettes were excluded and all rationales were retained. The seven remaining profile vignettes (see Appendix) included themes of suicidal ideation; drug abuse; statutory rape; domestic violence; physical abuse; intent harm to others; and risky sexual behaviors.

Each profile included the following scenario before participants were presented with the fictional profile:

You are a health care professional who has been seeing a patient regularly on an outpatient basis for the past year. The patient appeared to be stressed during the last appointment but did not disclose any information revealing the source of that stress. You decide to conduct an Internet search for your patient. The first website you visit is your patient’s public “MyFacePage” profile with no privacy settings where you discover this information.

Participants were presented with patients’ fictional SMS profiles. Each profile included: a screen name, a status update and time stamp; a profile of a 15-year-old female; location; mood; relationship status; activities; interests; two favorite quotes; and a sticker. The age and gender of the adolescent remained consistent throughout vignettes to ensure that these factors did not independently influence decision-making.

Following each profile, participants rated their concern level for the accessed information on a four-point Likert Scale (i.e., not at all concerning, somewhat concerning, moderately concerning, very concerning). Participants then chose what they would do first upon accessing such information. Choices included: nothing; immediately contact the patient and/or patient’s guardian; talk to the patient and/or patient’s guardian at the next scheduled appointment about the content of the profile, acknowledging the information was accessed; talk to the patient and/or patient’s guardian at the next scheduled appointment about the content of the profile, without acknowledging the information was accessed; or contact law enforcement and/or child protective services (CPS).

Participants were then instructed to choose up to three rationales explaining their decision. The choices included: duty to protect patient and/or others from harm; uncertainty about accuracy of information listed; ethically obligated; issues with informed consent; clinical intuition; patient’s right to confidentiality; legally obligated; belief that patient is asking for help; potential harm outweighs benefit; potential benefit outweighs harm; liability; concerns about rapport; and other.

Data Analysis Plan

Data was analyzed using a Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), Version 17. Reliability analyses were conducted to determine internal consistency of participants’ level of concern ratings for fictional SMS profiles. The internal consistency across vignettes was good (α = .84). Chi-square analyses were conducted to determine if differences existed between faculty and trainees in terms of SMS use; SMS beliefs; history of conducting SMS/Internet searches for patients; and responses to each SMS profile. One-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine differences between trainees’ and faculty members’ level of concern ratings for each vignette. To determine responses by discipline, the total count of each clinical decision across vignettes was calculated and frequency analyses were conducted for each decision by discipline.

To determine the extent that rationales contributed to each clinical decision, the total count of each rationale per clinical decision was calculated. Rationales that were selected in less than 10% of responses across vignettes were excluded from all analyses (i.e., issues with informed consent; liability; concerns about rapport patient; other). Frequency analyses were then conducted to examine clinical decisions by rationales.

RESULTS

Use of and Beliefs About Social Media Sites

Approximately 88% of providers reported having a personal SMS account (see Table 2). However, trainees were significantly more likely to have a SMS account and use it for longer periods of time than faculty (see Table 2). Faculty and trainees generally believed that it is not an invasion of privacy to conduct Internet/SMS searches of people they know and that SMS profiles with no privacy settings are public information. However, only trainees reported a history of conducting Internet/SMS searches for patiets (See Table 2). There were no differences in the extent that faculty and trainees communicated with existing/previous patients through SMSs.

Table 2.

Respondent Use of Social Media Sites

| Characteristic | Total count n |

Weighted % (N = 109) |

Faculty % (n = 29) |

Trainee % (n = 80) |

df | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have an online social media site account? |

||||||

| Yes | 96 | 88.07 | 72.41 | 93.75 | 1, N = 109 | 9.22** |

| No | 13 | 11.93 | 27.59 | 6.25 | ||

| Account use | ||||||

| < 1 hour per week | 53 | 49.07 | 82.76 | 37.50 | 1, N = 108 | 16.54** |

| 1 to 4 hours per week | 27 | 25.00 | 13.79 | 28.75 | 1, N = 108 | 2.31 |

| >4 hours per week | 28 | 25.93 | 3.45 | 33.75 | 1, N = 108 | 9.83** |

| Beliefs | ||||||

| Is it an invasion of privacy to conduct an Internet search for people you know or work with? |

||||||

| Yes | 24 | 22.02 | 24.14 | 21.25 | 1, N = 109 | .10 |

| No | 85 | 77.98 | 75.86 | 78.75 | ||

| Is it an invasion of privacy to conduct SMS searches of people you know or work with? |

||||||

| Yes | 23 | 21.10 | 31.03 | 17.50 | 1, N = 109 | 2.34 |

| No | 86 | 78.90 | 68.97 | 82.50 | ||

| Do you believe social media profiles with no privacy settings are public or private information? |

||||||

| Public | 94 | 86.24 | 89.66 | 85.00 | 1, N = 109 | .39 |

| Private | 15 | 13.76 | 10.34 | 15.00 | ||

| Practice | ||||||

| Have you ever conducted an Internet search for a patient or patient’s family member? |

||||||

| Yes | 14 | 12.84 | 0.00 | 17.50 | 1, N = 109 | 5.82* |

| No | 95 | 87.16 | 100.00 | 82.50 | ||

| Have you ever conducted a search for a patient’s SMS site (e.g., MySpace profile)? |

||||||

| Yes | 11 | 10.09 | 0.00 | 13.75 | 1, N = 109 | 4.44* |

| No | 98 | 89.91 | 100.00 | 86.25 | ||

| Have you ever communicated with a previous or existing patient through your SMS? |

||||||

| Yes | 7 | 6.42 | 3.45 | 7.50 | 1, N = 109 | .58 |

| No | 102 | 93.58 | 96.55 | 92.50 | ||

| Would you conduct an Internet search for patient for additional information? |

||||||

| Yes | 14 | 12.84 | 13.79 | 12.50 | 1, N = 109 | .03 |

| No | 95 | 87.16 | 86.21 | 87.50 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Responses to Patient Information Posted on Social Media Site Profiles

No significant differences existed between faculty and trainees’ ratings of level of concern across vignettes [Vignette A: F(1, 107) = .82, p = .37; Vignette B: F(1, 107) = 2.84, p = .10; Vignette C: F(1, 107) = .70, p = .40; Vignette D: F(1, 107) = 1.63, p = .20; Vignette E: F(1, 107) = .88, p = .35; Vignette F: F(1, 106) = .11, p = .74; Vignette G: F(1, 106) = .13, p = .72]. Differences in clinical responses were found in six of the seven SMS profiles (see Table 3). Findings suggest that trainees were more likely to talk to the patient at the next session without acknowledging that the information was accessed (significant differences in 5 out 7 vignettes). Faculty were more likely to contact a patient’s parent/guardian, law enforcement, or CPS (significant differences in 2 out of 7 vignettes). Regarding discipline-specific responses, behavioral health providers were most likely to talk to the patient at the next session without acknowledging that the information was accessed, whereas medical providers were most likely to immediately contact the patient’s parents or guardian (See Table 4).

Table 3.

Decisions About How to Best Respond to Accessed SMS Profile Information

| Vignette theme and response decision | Faculty (%) |

Trainee (%) |

df | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vignette A: Suicidal ideation decision | n = 29 | n = 80 | 1, N = 109 | |

| Nothing | 6.9 | 10.0 | .25 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

55.3 | 30.0 | 5.81* | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

10.3 | 20.0 | 1.38 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

17.2 | 38.7 | 4.45* | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

10.3 | 1.3 | 4.98* | |

| Vignette B: Drug use/references decision | n = 29 | n = 79 | 1, N = 108 | |

| Nothing | 20.7 | 17.7 | .12 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

6.9 | 16.5 | 1.62 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

41.4 | 22.8 | 3.66 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

24.1 | 43.0 | 3.22 | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

6.9 | 0.0 | 5.55* | |

| Vignette C: Underage sex decision | n = 29 | n = 78 | 1, N = 107 | |

| Nothing | 31.0 | 24.3 | .49 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

6.9 | 2.6 | 1.10 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

41.4 | 30.8 | 1.07 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

20.7 | 42.3 | 4.27* | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

0.0 | 0.0 | --- | |

| Vignette D: Child physical abuse decision | n = 29 | n = 79 | 1, N = 108 | |

| Nothing | 3.4 | 6.3 | .34 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

27.6 | 25.3 | .06 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

27.6 | 20.3 | .66 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

3.4 | 20.3 | 4.52* | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

38.0 | 27.8 | 1.02 | |

| Vignette E: Intent to harm others decision | n = 29 | n = 79 | 1, N = 108 | |

| Nothing | 3.4 | 8.9 | .91 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

48.4 | 31.6 | 2.54 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

17.2 | 17.7 | <.01 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

10.3 | 21.5 | 1.76 | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

20.7 | 20.3 | <.01 | |

| Vignette F: Statutory rape decision | n = 29 | n = 79 | 1, N = 108 | |

| Nothing | 6.9 | 13.9 | .99 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

17.2 | 11.4 | .64 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

44.9 | 30.4 | 1.97 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

17.2 | 40.5 | 5.10* | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

13.8 | 3.8 | 3.50 | |

| Vignette G: Domestic violence decision | n = 29 | n = 79 | 1, N = 108 | |

| Nothing | 3.4 | 6.3 | .34 | |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

44.9 | 35.4 | .79 | |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

27.6 | 20.3 | .66 | |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

6.9 | 29.1 | 5.89* | |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

17.2 | 8.9 | 1.51 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 4.

Decisions About How to Best Respond to Accessed SMS Profile Information by Discipline

| Percentage that each decision is selected by discipline across vignettes |

||

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Decision | Behavioral Health N = 68 (%) |

Medical N = 41 (%) |

| Na = 474 | Nb = 282 | |

| Nothing | 10.76 | 14.18 |

| Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian |

21.73 | 27.66 |

| Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed |

24.68 | 25.53 |

| Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed |

33.97 | 19.15 |

| Contact law enforcement or child protective services |

8.86 | 13.48 |

Note. Na = Total count of decisions across all seven SMS profile vignettes for behavioral health respondents; Nb = Total count of decisions across all seven SMS profile vignettes for medical respondents;

Rationales for Clinical Decision-Making

The extent that each rationale contributed to decision-making is displayed in Table 5. Duty to protect was the most common rationale for deciding to immediately contact a patient’s guardian, talk to the patient at the next session acknowledging information was accessed, or contact law enforcement/CPS. The most frequent rationale for talking to the patient at the next session without acknowledging that the information was accessed was uncertainty about the accuracy of information listed. Uncertainty was also the most prevalent rationale for deciding to do nothing.

Table 5.

Prevalence of Rationales for Each Clinical Decision

| Percentage (%) that each rationale is selected by decision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rationales for decisions |

Nothing (Na = 152) |

Immediately contact patient’s parents or guardian (Na = 485) |

Talk to patient at next session acknowledging information was accessed (Na = 485) |

Talk to patient at next session without acknowledging information was accessed (Na = 472) |

Contact law enforcement or child protective services (Na = 213) |

| Duty to protect |

0.0 | 31.4 | 23.5 | 22.0 | 31.9 |

| Uncertainty about accuracy of information listed |

42.1 | 10.9 | 19.6 | 25.8 | 4.2 |

| Ethically obligated |

0.0 | 20.4 | 16.5 | 7.4 | 21.1 |

| Clinical intuition |

7.9 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 7.4 | 3.3 |

| Legally obligated |

0.0 | 8.0 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 21.1 |

| Patient’s right to confidentiality |

29.0 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 10.8 | 0.5 |

| Belief patient is asking for help |

0.0 | 9.5 | 7.8 | 6.4 | 5.2 |

| Potential harm outweighs benefit |

19.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 5.7 | 1.0 |

| Potential benefit outweighs harm |

1.3 | 14.0 | 15.9 | 11.7 | 11.7 |

Note Na = Total count of rationales for each decision across all seven SMS profile vignettes.

DISCUSSION

The current study represents an important step in understanding the intersection between adolescent SMS use and pediatric clinical practices. The majority of faculty and trainees reported use of a SMS account. However, trainees were more likely to have an account and reported using their account more frequently. Faculty and trainees both believed that public SMS profiles represent public information and that it is not an invasion of privacy to conduct a SMS/Internet search of someone they know. Despite these similar beliefs, only trainees reported a history of conducting Internet/SMS searches for patients.

Differences were also found by discipline and between trainees and faculty in terms of how to best respond to concerning SMS information. Medical providers and behavioral health providers may make different decisions given their specialty training and timing of visits. That is, the vignettes contained themes of adolescent problems that are commonly managed by behavioral health providers, whereas these issues may not be regularly managed by medical providers. Further, behavioral health providers commonly meet with their patients weekly, whereas follow-up visits with a primary care medical provider may be annual. Thus medical providers may feel more urgency to immediately contact the family.

Regarding training level, trainees were far more likely to decide to talk to a patient at the next session without acknowledging that the information was accessed than faculty. The most common rationale for this decision was uncertainty about the accuracy of the SMS information listed; suggesting that trainees choose to gain additional information before making a decision about the validity of the SMS profile. However, by not acknowledging the information was accessed, trainees risk loss of trust within their professional relationship. Also, waiting places trainees at risk of not protecting patients from harm. Faculty were more likely to engage in immediate actions such as contacting the patient’s parent/guardian, law enforcement, or CPS than trainees, citing duty to protect as the most prevalent rationale for such decisions. Findings suggest that trainees and faculty fundamentally perceive and interpret SMS profile information differently.

These differences between faculty and trainees in responses are possibly due to a generational gap in technology immersion and training. Specifically, Prensky [22] argues that most current trainees grew up in a world where using technology (e.g., computers, Internet, text messaging, blogging, and social media sites) was already integrated within their education, patterns of establishing/ maintaining relationships, and means of self-expression. Faculty, who are typically older and trained before current students, are challenged to continually adopt and attempt to become fluent in new technology with which their students are likely more familiar.

Because faculty are likely less familiar with communication styles used on SMSs, it is reasonable to expect that their perceptions of posted SMS information differs from trainees. Given trainees’ increased exposure to SMSs, they may be desensitized to the types of content posted and more familiar with popular culture themes and social communication styles than faculty. Also, trainees may be more aware that users may post exaggerated information which is not necessarily reflective of their current psychological state to generate attention or discussion amongst friends. Therefore, trainees may view immediately responding to posted information as irresponsible without further evaluation.

Although trainees are likely more fluent in the use of SMSs, faculty are tasked with providing their students with guidance about the use of SMSs within practice. In particular, trainees who have grown up immersed in the use of the Internet may lack awareness of the clinical (e.g., negative impact on provider-patient relationship) and ethical implications (e.g., informed consent, professional relationship boundary violations) of seeking information about patients online [8]. This represents a unique training challenge as faculty may need to educate themselves as well as be educated by trainees about SMS use to provide effective supervision. In fact, discussions between faculty and trainees about the use of SMSs within practice provide the unique opportunity for bi-directional and cross-generational education. Such discussions may lead to more reliable decisions between faculty and trainees that are based on both existing ethical guidelines as well as a better understanding of SMS social communication styles.

There clearly is a need for policies and guidelines regarding the role of SMSs in clinical practice. The first question that needs to be asked in the development of these policies is: Should healthcare providers access patient information from SMS profiles? If the answer is “yes,” policies need to specifically address issues of informed consent and patient education to provide guidance to this uncertain area of practice.

In the current study, “issues with informed consent” was rarely selected (< 10%) as a rationale for clinical responses. However, within each vignette the clinician conducted an internet search without the informed consent of the patient which could ultimately result in avoidable harm to the patient and/or the provider-patient relationship [8]. While such acts may be perceived as ethical violations across medical and behavioral health disciplines, these ethical guidelines did not appear to influence health providers’ decision-making [8, 14, 16, 17].

The implementation of SMS-specific policies within practice may increase the likelihood that healthcare providers apply existing ethical guidelines within their decision-making. Therefore, the following SMS-specific recommendations are offered for medical and behavioral health disciplines. It is highly recommended that providers never seek patient information from the Internet without explicitly gaining the patient’s consent [8]. Further, it should not be assumed that adolescents possess the insight about how SMS postings may be perceived by others and/or technological understanding of how to increase security settings to limit the people that can view their profile [8]. Therefore, if a healthcare provider plans to seek patient information from a SMS, then the provider needs to comprehensively educate the patient about the risks and benefits of how such information might impact the patient’s functioning and services. Even after a family has been educated and the adolescent provides informed assent and a legal guardian provides informed consent, it is highly suggested that providers only seek SMS information in open collaboration with their patients [8]. Given that adolescents use SMSs as a method of expressing their identity [23], the exploration of the patient’s profile together may provide meaningful information that may positively impact services being provided. In addition, collaborative exploration of SMSs gives the provider the opportunity to directly ask questions about any concerning information posted by the patient.

While this study represents an important step in understanding how SMSs are utilized in clinical practices and differences in SMS decision-making, there were some limitations. The study employed vignettes that could not possibly include the range of information that a provider would have in actual practice. Further, case vignettes were limited to one age and gender and decisions may have differed if adolescent profile vignettes included varying ages and gender. Also, participants were required to respond to vignettes as though they had already accessed the patient’s SMS. However, most had not previously conducted searches for patients. Clinical responses were limited to five different decisions and additional decisions (e.g., consult with supervisor/colleague) exist in actual practice. Further, participants were not provided the opportunity to elaborate about their technique for eliciting additional information from patients if they decided to act immediately or wait until the next session. This information would have provided a better understanding of clinical responses and potentially other areas of needed training. The sample was limited to faculty and trainees from one medical school and findings may not generalize to other practices. Due to limited sample size, medical and behavioral health providers were combined into groups of faculty and trainees and discipline-specific faculty/trainee differences may exist.

In conclusion, SMSs represent an intriguing social medium for how people relate to one another and are likely to continue to expand in how they are utilized (e.g., posting your physical location on your SMS profile using a Global Positioning System). Healthcare providers are charged with staying current on how their adolescent patients utilize SMS sites to ensure that providers stay at the forefront of promoting their patients’ healthy functioning and safety. Beyond the need for developing discipline-specific guidelines, the prevalence of conducting Internet/SMS searches for patients within practice needs to be further explored in a nationally representative sample. Further research is needed to explore how bi-directional models of training impact faculty members’ fluency with SMSs and trainees’ use of SMS within clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the NIH Health Behavior Research in Minority Pediatric Populations Training Grant (#5T32HD07510-08) and the University of Miami ARSHT Ethics and Community Research Grant (#700743).

Appendix. Fictional Social Media Site Profile Vignettes

Vignette A: Suicidal Ideation

Vignette B: Drug Use/References

Vignette C: Underage Sex

Vignette D: Child Physical Abuse

Vignette E: Intent to Harm Others

Vignette F: Statutory Rape

Vignette G: Domestic Violence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lenhart A. Adults and social network websites. [Accessed August 19, 2010];Pew Internet and American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/Adults-and-Social-Network-Websites/1-Summary-of-findings.aspx. Published January 14, 2009.

- 2.Lenhart A, Madden M. Social networking websites and teens: An overview. [Accessed August 16, 2010];Pew Internet and American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2007/Social-Networking-Websites-and-Teens.aspx. Published January 7, 2007.

- 3.Nielsen Online. [Accessed August 16, 2010];Top ten global parent companies May 2010, home & work. Available at: http://en-us.nielsen.com/content/nielsen/en_us/insights/rankings/internet.html.

- 4.Boyd DM, Ellison NE. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2008;13:210–230. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valkenburg PM, Peter J, Schouten AP. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents’ well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:584–590. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodge MJ. The Fourth Amendment and privacy issues on the “new” Internet: Facebook.com and Myspace.com. South Ill Univ Law J. 2006;31:95–123. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagatic TN, Johnson NA, Jakobsson M, et al. Social phishing. Commun ACM. 2007;50:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehavot K, Barnett JE, Powers D. Psychotherapy, professional relationships, and ethical considerations in the MySpace generation. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2010;41:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamberlin J. Too much information: Cautiously post content to your personal Web site or blog, faculty and students advise. [Accessed August 4, 2010];gradPSYCH. 2007 5 http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2007/03/information.aspx.

- 10.Guseh JS, II, Brendel RW, Brendel DH. Medical professionalism in the age of online social networking. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:584–586. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.029231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno MA, Fost NC, Christakis DA. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008;121:157–161. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Personal information of adolescents on the Internet: A quantitative content analysis of MySpace. J Adolesc. 2008;31:125–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Child abuse, confidentiality, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Pediatrics. 2010;125:197–201. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Medical Association. [Accessed August 16, 2010];AMA’s code of medical ethics. 1992 Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics.shtml.

- 15.American Medical Association. [Accessed August 16, 2010];Legal issues for physicians: Patient-physician relationship issues. 2009 Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/legal-topics/patient-physician-relationship-topics.shtml.

- 16.American Psychological Association. [Accessed August 16, 2010];Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. 2002 Available at: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx.

- 17.National Association of Social Workers. [Accessed August 16, 2010];Code of ethics. 2008 Available at: http://www.naswdc.org/pubs/code/code.asp.

- 18.Shain BN the Committee on Adolescence. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120:669–676. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarasoff v Regents of the University of California, 551 P.2d 334 (Cal 1976).

- 20.Manago AM, Graham MB, Greenfield PM, et al. Self-presentation and gender on MySpace. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2008;29:446–458. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garner v Stone, No. 97A-30250-1 (Ga. DeKalb County Super 1999).

- 22.Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon. 2001;9:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehdizadeh S. Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2010;13:357–364. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]