Abstract

Biologic scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix (ECM) have been used successfully in preclinical models and humans for constructive remodeling of functional, site-appropriate tissue after injury. The mechanisms underlying ECM-mediated constructive remodeling are not completely understood, but scaffold degradation and site-directed recruitment of both differentiated and progenitor cells are thought to play critical roles. Previous studies have shown that degradation products of ECM scaffolds can recruit a population of progenitor cells both in vitro and in vivo. The present study identified a single cryptic peptide derived from the α subunit of the collagen III molecule that is chemotactic for a well-characterized perivascular stem cell in vitro and causes the site-directed accumulation of progenitor cells in vivo. The oligopeptide was additionally chemotactic for human cortical neural stem cells, rat adipocyte stem cells, C2C12 myoblast cells, and rat Schwann cells in vitro. In an adult murine model of digit amputation, treatment with this peptide after mid-second phalanx amputation resulted in a greater number of Sox2+ and Sca1+,Lin− cells at the site of injury compared to controls. Since progenitor cell activation and recruitment are key prerequisites for epimorphic regeneration in adult mammalian tissues, endogenous site-directed recruitment of such cells has the potential to alter the default wound healing response from scar tissue toward regeneration.

Introduction

Biologic scaffolds composed of extracellular matrix (ECM) have been used successfully to promote site-specific, functional remodeling of soft tissue in both preclinical animal models1–10 and human clinical applications.11–14 Secreted by the cells of each tissue, ECM is highly conserved among many species and consists of molecules such as collagen, fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, glycosaminoglycans, and growth factors oriented in a specific three-dimensional structure and composition optimized for each tissue of origin.15,16 Although the mechanisms of ECM scaffold-mediated constructive remodeling are not fully understood, stem cell recruitment17,18 and the release of bioactive peptides by protease-mediated ECM degradation are thought to play a role in the constructive remodeling process.19–21 In addition to possessing antimicrobial properties,22–25 cryptic bioactive peptides derived from degradation of ECM components have been shown to be capable of initiating and potentiating constructive remodeling pathways such as angiogenesis, mitogenesis, and chemotaxis of site-specific cells.26–28 Degradation products from ECM bioscaffolds have also been shown to recruit progenitor cells in vitro29–31 and in vivo.32 Thus, degradation products of ECM may be a therapeutic option for promoting site-directed recruitment of endogenous tissue progenitor cells for constructive remodeling of tissue after injury.

The present study identified a single cryptic peptide derived from protease-mediated degradation of an ECM bioscaffold derived from porcine urinary bladder that can promote in vitro migration of multiple cell types, including progenitor cells. Furthermore, the present study showed that the isolated peptide was capable of promoting localized accumulation of progenitor populations to a site of injury in vivo, many of which express markers of multipotency.

Materials and Methods

Overview of experimental design

The experimental methods were designed to systematically isolate a single matricryptic peptide that exhibits chemotactic potential for a well-characterized population of human perivascular stem cells30 previously shown to migrate toward degradation products of ECM in low and high oxygen conditions.32,33 Matricryptic peptides were prepared by enzymatic degradation of biologic scaffolds derived from urinary bladder ECM, and subsequent serial fractionation of the resulting degradation products by ionic charge, size, and hydrophobicity. At each step, a transwell assay was utilized to determine the chemotactic potential of each eluted fraction for these stem cells. After isolation of a single cryptic peptide, the peptide was then synthesized and its chemotactic potential was evaluated for multiple types of progenitor cells and differentiated cells. Finally, an established model of adult murine digit amputation28 was utilized to evaluate the ability of the cryptic peptide to promote the site-specific accumulation of progenitor cells in vivo. In all cases, statistical significance was determined by two-tailed Student's t-test with α=0.05 and β=0.2.

Decellularization of tissue and preparation of ECM degradation products

Porcine urinary bladders were harvested from euthanized market weight (240–260 lb) pigs. The basement membrane and underlying lamina propria were isolated and harvested as previously described.34 After treatment with peracetic acid, ethanol, deionized H2O, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lyophilized sheets were comminuted and digested in 0.1 mg/mL pepsin and 0.01 N HCl for 48 h before neutralization and dilution in PBS to yield a 5 mg/mL solution.31

Isolation of chemotactic peptide

Peptides of pepsin-digested urinary bladder matrix (UBM) were fractionated via ammonium sulfate precipitation. Fractions were analyzed for protein content via BCA assay (Thermo) and chemotactic ability (as described below). Molecules in the 0%–20% fraction of ammonium sulfate precipitation were discarded to remove the most gelatinous fractions and leave a solution suitable for subsequent chromatographic separation. The remaining 20%–80% ammonium sulfate precipitant was isolated, dialyzed into PBS, and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-4 (Millipore) devices. Concentrated protein was fractionated via two G3000SWXL HPLC size exclusion columns (Tosoh) in series at 0.5 mL/min in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl. Each fraction was analyzed for protein content and chemotactic ability.

Larger post size exclusion chromatography chemotactic fractions were pooled and adjusted to pH 8.8 in 50 mM Tris buffer and loaded onto a 1 mL HiTrap Q ion exchange column at 0.5 mL/min. Bound peptides were washed in buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.8) before fractionation using 0.2, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, and 1.0 M salt concentrations in the same buffer. Factions were dialyzed into PBS, and analyzed for protein concentration and chemotactic properties. Fractions showing chemotactic ability were concentrated via centrifugal filtration and injected onto an Octadecyl 4PW reverse phase column (Tosoh) and eluted over a 0%–80% gradient of methanol in 10 mM ammonium carbonate buffer at 0.5 mL/min. Fractions were concentrated via centrifugal evaporation, resuspended in H2O, and analyzed for protein abundance and chemotactic properties. The peptide that revealed maximal chemotactic ability per mg of chemoattractant was further characterized by mass spectrometry (NextGenSciences) and then chemically synthesized (GenScript). A BLAST search for sequence homology was conducted using the nonredundant protein sequences (nr) database and Blastp algorithm. Parameters of the search were as follows: (1) max target sequences=100, (2) expect threshold=200,000, (3) word size=2, (4) Matrix=PAM30, (5) gap cost existence=9 and extension=1, and (6) no compositional adjustments.

Source of cells and culture conditions

Human perivasular stem cells were a gift from Dr. Bruno Peault, and these cells were isolated and prepared as previously described.30 Perivascular stem cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Human cortical neuroepithelium stem (CTX) cells were a gift from ReNeuron™. CTX cells were cultured in DMEM:F12 supplemented with 0.03% Human albumin solution, 100 μg/mL human Apo-Transferrin, 16.2 μg/mL Putrescine DiHCl, 5 μg/mL Insulin, 60 ng/mL Progesterone, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 40 ng/mL Sodium Selinite, 10 ng/mL human bFGF, 20 ng/mL human Epidermal growth factor, and 100 nM 4-Hydroxytestosterone. Human adipose stem cells were isolated as previously described,35 and cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. C2C12 muscle myoblast cells, IEC-6 intestinal epithelial cells, RT4-D6P2T rat Schwann cells, and HMEC human microvascular endothelial cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured following ATCC guidelines.

Transwell cell migration assays

Chemotaxis assays were conducted in a transwell as described previously.31 Perivascular stem cells were grown in culture medium to ∼80% confluence and starved overnight in DMEM containing 0.5% heat-inactivated serum. After starvation, cells were resuspended in DMEM at a concentration of 6×105 cells/mL for 1 h. Polycarbonate PFB filters (Neuro Probe) with 8 μm pores were coated with 0.05 mg/mL Collagen Type I (BD Biosciences). The number of cells that migrated toward the lower chamber through 8 μm pore polycarbonate PFB filters (Neuro Probe) was determined after 5 h. The lower wells contained different amounts of the ECM peptide fraction of interest. Migrated cells were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and quantified with ImageJ (NIH). All of the data are reported as the mean value of triplicate determinations with standard deviations. The assay was performed on three separate occasions. C2C12, IEC-6, RT4-D6P2T, and HMEC cells were grown to 80% confluence, and starved in serum-free media overnight before placement in the transwell assay. CTX cells were grown to ∼80% confluence and were unstarved before resuspension and placement in the transwell assay. All other methods were identical for each cell type.

Animal model of digit amputation

All methods were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh and performed in compliance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mid-second phalanx digit amputation of the third digit on each hindfoot in adult 6–8-week-old C57/BL6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) was completed as previously described.32 After amputation, digits were either treated with a subcutaneous injection of 15 μL of 10 mM peptide, or the same volume of PBS as a carrier control (n=4 for each group). Treatments were administered at 0, 24, and 96 h post-surgery. Animals were sacrificed via cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia (5%–6%) at day 7 post-surgery. Digits were either fixed and sectioned for histologic analysis and immunolabeling (described below), or harvested for cell isolation for subsequent fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS analysis, cytospin, or immunolabeling; described below).

Tissue immunolabeling

Harvested mouse digits were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and decalcified for 2 weeks in 5% formic acid before being paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained for Sox2 (Millipore, AB5603), Sca1 (Abcam, ab25196), or Ki67 (Abcam, ab15580). After deparaffinization, antigen retrieval in 10 mM citrate buffer (citrate: C1285; Spectrum) was performed for 25 min at 95°C. Slides were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Slides were then rinsed in PBS, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide solution in PBS for 30 min, washed, and incubated for 1 h with HRP-conjugated anti-rat IgG (P0450; Dako) or anti-rabbit IgG (P0448; Dako) antibodies, washed, and developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Vector Labs). All primary antibodies were diluted 1:100 in blocking solution, and all secondary antibodies were diluted 1:200 in blocking solution.

After staining with DAB, all slides were counter-stained with Harris' hematoxylin, dehydrated, coverslipped with nonaqueous mounting medium, and imaged. Images were taken at 40×magnification and 200×magnification. For quantification of the number of cells positive for markers, three images were taken for each sample: distal to the amputated edge of the bone, and lateral to the cut edge of the bone on either side. The number of positive cells in each image was counted by three independent investigators who were blinded to the treatment group. The mean number of positive cells was compared between various groups by a two-sided, unpaired Student's t-test with unequal variance. Significance was determined at p=0.05 level (α=0.05, β=0.2).

Flow cytometric analysis

Amputated digits were harvested and placed into cold culture medium consisting of DMEM, 10% mesenchymal stem cell-grade FBS (Invitrogen), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.1 mg/mL ciprofloxacin (USP, 1134313). Using a microdissection microscope and aseptic technique, the epidermis and dermis were removed and the soft tissue distal to the amputated second phalanx bone was harvested into serum free DMEM containing 2% Collagenase Type II (Gibco Invitrogen, 17101–015) for 30 min at 37°C, filtered through a 70 μm filter, counted, and prepared for flow cytometric analysis expression of Sca1 (Abcam, ab25031) or markers of differentiated blood-derived cells (Lineage cocktail, 559971). Cells were filtered through a 70 μm filter and incubated in primary antibody for 1 h, washed, and then incubated in a streptavidin APC-Cy7-conjugated secondary antibody (554063; BD Biosciences) for 1 h before washing and flow cytometric analysis.

Cytospin and cell immunolabeling

After cytospin of 1×104 cells per slide, each slide was fixed in methanol for 30 s and stored at −20°C. Before staining, slides were rehydrated in PBS for 5 min, and cells were permeablized in 0.1% TritonX/PBS for 15 min. Slides were blocked in 1% BSA/PBS for 1 h before overnight incubation with goat anti-Sox2 (1:50) (SantaCruz, Y-17, sc17320), rabbit anti-Sox2 (1:100) (Millipore, AB5623), rat anti-Sca1-FITC (1:50) (Abcam, ab25031), or rabbit anti-phospho-Histone-H3 (1:100) (Abcam, ab32107) primary antibody diluted in blocking solution. After two washes in PBS, slides were incubated for 1 h with donkey anti-goat IgG-Alexa Fluor 350 (1:100) (Invitrogen, A21081) and/or donkey anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 546 (1:250) (Invitrogen, A10040) diluted in blocking solution. After two washes in PBS, slides were counterstained with DRAQ5 (1:500) (Cell Signal, 4084) diluted in PBS for 30 s before three washes in PBS and coverslipping with fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, S3023). All images were taken at 200×magnification.

Results

Isolation, identification, and synthesis of chemotactic cryptic peptide

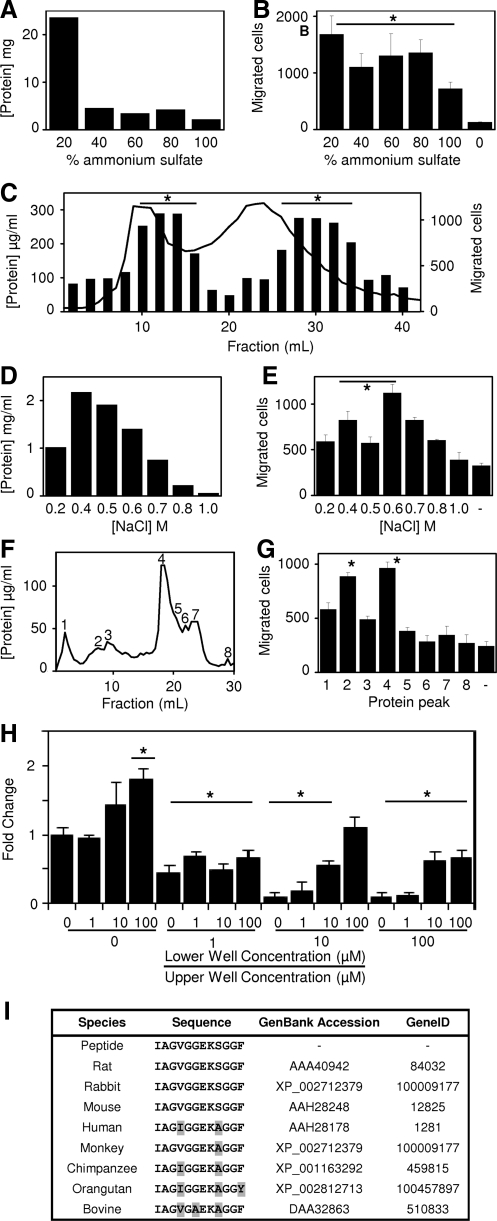

The various protein fractions after ammonium sulfate precipitation were dialized against PBS and all fractions showed chemotactic activity (migration of the perivascular stem cells to the bottom well of the transwell chambers) compared to the PBS control (Fig. 1a, b). The fractions were pooled, concentrated, and further fractionated via size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1c). Protein quantification showed that the peptide fragments distributed into two peaks, with a long tail of small size molecules. Analysis of each fraction showed that the chemotactic effect was also distributed into two peaks. However, these chemotactic peaks were not aligned with the protein peaks. Chemotactic activity of each fraction did not correlate with the total amount of protein, but rather was a net effect of the distribution of specific molecules with the UBM peptide mix.

FIG. 1.

Identification of chemotactic peptide. Urinary bladder matrix digest was fractionated and chemotactic ability quantified against perivascular stem cells by ammonium sulfate (A, B), size exclusion (C), ion exchange (D, E), and reverse phase (F, G) chromatography. Peptide was identified via mass spectroscopy and synthesized to assay for chemotactic potential for human perivascular stem cells (H). A BLAST search for the isolated peptide sequence showed over 75% homology with the Collagen IIIα molecule over eight separate species (I). Error bars are mean±SD. *p<0.05 as compared to negative control. SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of the second chemotactic peak showed these molecules to be too small to bind to ion exchange beads carrying either a positive or negative charge resulted in very little capture. Thus, the most chemotactic fractions from the first size exclusion peak were pooled and refractionated via ion exchange chromatography (Fig. 1d). After adjustment to pH 8.8, the remaining peptides were bound to a HiTrap Q ion exchange column, washed in salt-free buffer, and eluted over a series of increasing concentrations of salt. The fractions were adjusted to a biological buffering condition and analyzed for chemotactic activity (Fig. 1e). The fraction with the greatest chemoactivity per mg/mL of protein was chosen for further study. The fraction with the greatest chemotactic activity per mg/mL of protein was the 0.6 M fraction. The 0.6 M fraction was further fractionated by reverse phase chromatography (Fig. 1f). Unbound peptides (peak 1) and bound peptides were eluted over a 0%–80% methanol gradient and analyzed for protein concentration. Protein peaks were then evaluated for chemotactic activity (Fig. 1g). Fractions 2 and 4 showed the greatest amount of chemotactic activity, and lesser chemotactic activity was also shown in the unbound fraction. Because Fraction 2 showed the greatest chemoactivity per mg of protein, this fraction was isolated for sequence analysis by mass spectrometry. Analysis showed that the fraction consisted predominantly of a single peptide with the amino acid sequence of IAGVGGEKSGGF, a sequence identical to a string of amino acids from the C-terminal telopeptide of collagen IIIα. The peptide was chemically synthesized and evaluated in the same transwell chemotactic assay over a range of concentrations (Fig. 1h). Chemokinetic activity as a cause of the cell migration was ruled out by varying the relative concentrations of the peptide in the upper and lower wells of the transwell chambers (Fig. 1h). A BLAST search of the isolated peptide sequence showed that the peptide sequence was highly conserved in collagen IIIα among eight mammalian species, including human (Fig. 1i).

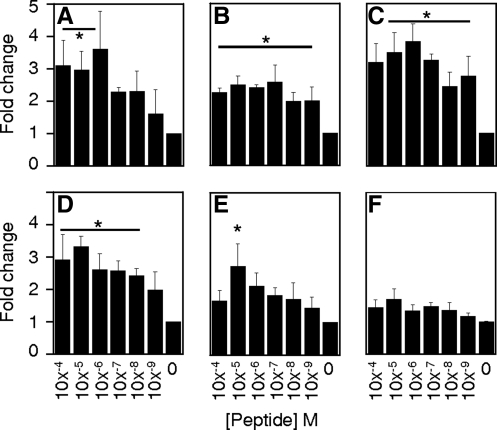

Cryptic peptide shows in vitro chemotactic activity toward several cell types

The synthesized peptide showed positive chemotactic activity toward human neuroepithelial cells (Fig. 2a), human adipose stem cells (Fig. 2b), C2C12 mouse myoblast cells (Fig. 2c), the RT4-D6P2T rat Schwann cell line (Fig. 2d), and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC) (Fig. 2e). The rat intestinal cell IEC-6 line (Fig. 2f) was unresponsive to the peptide.

FIG. 2.

Peptide promotes migration of multiple cell types in vitro. The chemotactic ability of the peptide was tested over six orders of magnitude concentration against human neuroepithelial cortical (CTX) stem cells (A), human adipose stem cells (B), mouse myoblast (C2C12) cells (C), rat Schwann (RT4-D6P2T) cells (D), human microvascular endothelial (HMEC) cells (E), and rat intestinal epithelial (IEC6) cells (F). Error bars are Mean±SD. *p<0.05 as compared to negative control.

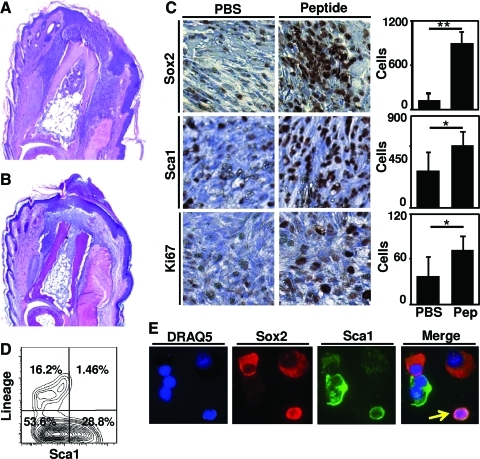

Cryptic peptide shows in vivo recruitment of cells positive for Sox2 and Sca1

Histologic examination of peptide-treated digits at day 7 post-amputation showed a dense, cellular infiltrate both lateral and distal to the site of amputation, concomitant with an invaginating epithelium and incomplete basement membrane (Fig. 3a). The PBS-treated digits showed a less dense cellular infiltrate concomitant with scar tissue deposition and a mature epithelium consistent with a typical wound healing response in the murine digit (Fig. 3b).36 Immunolabeling studies showed a 6.6-fold increase in Sox2+ cells and a 1.6-fold increase in Sca1+ cells at the site of amputation after peptide treatment as compared to PBS treatment (Fig. 3c). FACS analysis of the Sca1+ cells showed that the Sca1+ cells did not co-express markers of differentiated blood lineage (Fig. 3d). Isolated cells that were co-immunolabeled for both Sox2+ and Sca1+ confirmed co-expression of Sca1 and Sox2 in a subset of cells (Fig. 3e).

FIG. 3.

Peptide treatment results in greater number of cells in vivo. Adult mouse hind foot digits were amputated at the mid-second phalanx and treated with 15μL of either PBS or peptide. Histologic examination by hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a thinner, invaginating epithelium concomitant with a denser cellular response after peptide treatment (A) as compared to PBS carrier control treatment (B). Histologic sections showed that peptide treatment led a greater number of Sox2, Sca1, and Ki67-positive cells at the site of amputation (C). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that Sca1+ cells did not express markers of differentiated blood lineage (D). Co-expression of Sca1 and Sox2 was observed in subsets of cells after cytospin and co-immunolabeling (arrow) (E). Images were taken at 40×magnification (A, B), 630×magnification (A, B), or 400×magnification (C, E). Error bars are Mean±SD. *p<0.05. **p<0.01. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

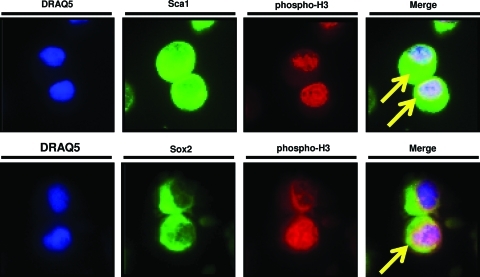

Histologic sections from peptide-treated and PBS-treated digits were also stained for Ki67 to evaluate cell proliferation. At day 7 postamputation, peptide treatment led to a 1.9-fold increase in Ki67+ cells at the site of amputation (Fig. 3b). Cells were located both lateral and distal to the plane of amputation. To confirm that Sox2+ and Sca1+ cells were undergoing mitosis, accumulated cells were isolated and co-immunolabeled for phosphorylated Histone H337 and either Sox2 or Sca1. Subsets of both Sox2+ cells and Sca1+ cells also showed pan-nuclear expression of phosphorylated Histone H3 (Fig. 4), consistent with ongoing mitosis.37

FIG. 4.

To confirm that Sca1+ and Sox2+ cells were actively proliferating, isolated cells were cytospun and co-immunolabeled for either Sca1 or Sox2 and a marker of cells in the M phase of the cell cycle, phosphorylated Histone H3.37 Subsets of Sca1+ and Sox2+ co-expressed nuclear Histone H3 (arrows). Images were taken at 400×magnification. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

Discussion

The present study identifies a novel matricryptic peptide with in vitro chemotactic activity for several types of progenitor cells and differentiated cells. This peptide is also associated with the increased presence of Sox2+ and Sca1+,Lin− cells at the site of experimentally induced injury in a mouse model. As a short 12 amino acid oligopeptide derived from the C-terminal telopeptide region of the collagen IIIα molecule, the sequence of this molecule is highly conserved amongst at least eight mammalian species.

The C-terminal telopeptide region of fibrillar collagen is known to be a site of interchain cross-linking of cysteine residues that ultimately stabilize the triple helix structure of collagen.38 Thus, in the absence of injury and protease-mediated degradation, it is unlikely that such a sequence would actively interact with cells due to extensive cross-linking. However, protease-mediated matrix degradation at a site of injury would not only destabilize and release peptides from the triple helical domain of collagen, but also expose and cleave the telopeptide regions of collagen to release cryptic peptides similar in sequence to the isolated peptide in the present study. Previous studies have shown that telopeptide sequences can be isolated in the circulating blood after turnover of collagen and soft tissue remodeling in a clinical setting.39–41 Thus, while the cryptic peptide in the present study was isolated by nonphysiologic methods of degradation, it is likely that a similar peptide can and would be released in vivo at a site of injury.

The concept of cryptic fragments of parent matrix molecules having biologically relevant properties is not new. Antimicrobial activity of matricryptic peptides in the form of defensins,22 cecropins,23,24 and magainins25 has been identified by many groups and is thought to represent an evolutionary survival advantage in response to injury. Angiogenic and anti-angiogenic cryptic peptides such as endostatin,42 restin,43 and arrestin44 have been described and have been used therapeutically for a variety of conditions. Such cryptic peptides can be released from ECM by proteases secreted by immune cells at a site of injury, and thus logically represent a desirable aspect of the host response to tissue injury.

The recruitment of various cell types such as stem and progenitor cells, endothelial cells, and muscle precursor cells to sites of tissue injury represents a logical and plausible host response to support tissue reconstruction. The mechanisms underlying such a recruitment process are largely unknown, but it is feasible that cryptic peptides represent one such strategy. The manner in which the oligopeptide described herein was generated was nonphysiologic, but a previous study has shown naturally occurring degradation products after ECM-mediated tissue reconstruction have similar properties.45 In fact, degradation products of ECM have been shown to regulate the site-directed recruitment of differentiated26–28 and progenitor cells29,31,32 in vivo.

Site-specific recruitment of multipotent progenitor cells in response to limb amputation is a prerequisite for blastemal based epimorphic regeneration in species such as newts and axolotls.46 Soluble factors are present that can recruit selected cell types and selected genetic programs are activated to participate in the regeneration process that results in a perfect phenocopy of the missing tissue structure.46–48 While blastema formation does not occur after injury in adult mammalian species, recruitment to and/or directed differentiation of tissue specific progenitor cells at the site of injury has the potential to alter the default scar tissue wound healing response toward a more constructive tissue remodeling response.49,50 In organs such as the liver, bone marrow, and intestinal lining that are capable of mounting a regenerative response to injury, activation and recruitment of progenitor cell compartments is an important prerequisite to site-appropriate tissue regeneration.51–53 Thus, recruitment of multipotent progenitor cells to a site of injury in response to placement of a chemotactic peptide may be considered as a form of endogenous stem or progenitor cell therapy. The clinical efficacy of such therapies, however, remains to be determined.

The present study identified a single peptide derived from a mixture of matricryptic peptides that can recruit stem, progenitor, and differentiated cells in vitro and is associated with an increased accumulation of such cells at sites of injury in vivo. However, the findings of the present study do not preclude the existence of other pro- and anti-chemotactic matricryptic peptides. It is likely that degradation of ECM leads to release of a large mixture of anti- and pro-chemotactic peptides that yields an overall net effect in vivo. Indeed, certain fractions of the ammonium sulfate precipitated peptides in the present study showed inhibited migration of progenitor cells, a finding suggesting that degradation products of ECM such as UBM contain chemotactically positive, negative, and likely also neutral peptides. Isolation of these peptides was not pursued. Although an active peptide described in the present study was isolated from a mix of mammalian matricryptic peptides, the naturally occurring contribution of this particular peptide to the host response to injury was not determined. The present study also showed the efficacy of the isolated oligopeptide in an adult mammalian model of digit amputation via local accumulation of progenitor cells at the site of injury. While the present study cannot determine whether the efficacy of the isolated peptide is dependent on the type of injury, future studies will further investigate the potential role of the peptide in progenitor cell recruitment in various other types of injury.

Additionally, the present study focused on identifying a bioactive cryptic fragment of one source of ECM. ECM derived from the porcine urinary bladder has been used in multiple pre-clinical applications for site-specific remodeling of a variety of soft tissues.54–63 However, commercially available biologic scaffolds composed of ECM are derived from a number of species and organs.64 It is possible, and in fact likely, that a similar cryptic peptide would be found in ECMs from other sources. Collagen III is a common constituent of many soft tissues from which ECM scaffolds are made, and its sequence is highly conserved from species to species. The present study found that the isolated cryptic peptide's sequence is also highly conserved among over eight species, many of which are already used as sources of ECM for commercial applications. Thus, it is likely and expected that the isolated cryptic peptide, or a similar derivative of such a peptide, would qualitatively possess the same bioactive properties in multiple mammalian species and commercially available ECM scaffolds.

In summary, the present study identifies a chemotactic matricryptic peptide capable of site-directed accumulation of selected progenitor cells and differentiated cells in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, treatment of an injury site in a murine model of digit amputation with this peptide is associated with the accumulation of endogenous Sox2+ and Sca1+,Lin− cells. In the present study, the recruited cells clearly did not spontaneously differentiate and form functional tissue. Nevertheless, the findings of the present study provide a potential strategy for endogenous stem cell recruitment to a site of injury. The next logical step in promoting tissue regeneration of more complex tissues will involve identifying strategies by which to direct the spatiotemporally appropriate proliferation and differentiation of the multipotent progenitor cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Deanna Rhoads and the McGowan Histology Center for assistance in histologic section preparation and Chris Medberry for his assistance in production of the ECM bioscaffolds. This work was supported by the Armed Forces Institute for Regenerative Medicine grant W81XWH-08–2-0032 and NIH training fellowship grant 1F30-HL102990.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Caione P. Capozza N. Zavaglia D. Palombaro G. Boldrini R. In vivo bladder regeneration using small intestinal submucosa: experimental study. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:593. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb M.A. Badylak S.F. Janas W. Boop F.A. Histology after dural grafting with small intestinal submucosa. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:389. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00202-9. discussion 393, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lantz G.C. Badylak S.F. Coffey A.C. Geddes L.A. Blevins W.E. Small intestinal submucosa as a small-diameter arterial graft in the dog. J Invest Surg. 1990;3:217. doi: 10.3109/08941939009140351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodde J.P. Badylak S.F. Shelbourne K.D. The effect of range of motion on remodeling of small intestinal submucosa (SIS) when used as an achilles tendon repair material in the rabbit. Tissue Eng. 1997;3:27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uygun B.E. Soto-Gutierrez A. Yagi H. Izamis M.L. Guzzardi M.A. Shulman C., et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularized liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nat Med. 2010;16:814. doi: 10.1038/nm.2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ott H.C. Clippinger B. Conrad C. Schuetz C. Pomerantseva I. Ikonomou L., et al. Regeneration and orthotopic transplantation of a bioartificial lung. Nat Med. 2010;16:927. doi: 10.1038/nm.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott H.C. Matthiesen T.S. Goh S.K. Black L.D. Kren S.M. Netoff T.I., et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Badylak S. Meurling S. Chen M. Spievack A. Simmons-Byrd A. Resorbable bioscaffold for esophageal repair in a dog model. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1097. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.7834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badylak S.F. Lantz G.C. Coffey A. Geddes L.A. Small intestinal submucosa as a large diameter vascular graft in the dog. J Surg Res. 1989;47:74. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(89)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zalavras C.G. Gardocki R. Huang E. Stevanovic M. Hedman T. Tibone J. Reconstruction of large rotator cuff tendon defects with porcine small intestinal submucosa in an animal model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:224. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalf M.H. Savoie F.H. Kellum B. Surgical technique for xenograft (SIS) augmentation of rotator-cuff repairs. Oper Tech Orthop. 2002;12:204. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derwin K.A. Badylak S.F. Steinmann S.P. Iannotti J.P. Extracellular matrix scaffold devices for rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:467. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mase V.J., Jr. Hsu J.R. Wolf S.E. Wenke J.C. Baer D.G. Owens J., et al. Clinical application of an acellular biologic scaffold for surgical repair of a large, traumatic quadriceps femoris muscle defect. Orthopedics. 2010;33:511. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100526-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witteman B.P. Foxwell T.J. Monsheimer S. Gelrud A. Eid G.M. Nieponice A., et al. Transoral endoscopic inner layer esophagectomy: management of high-grade dysplasia and superficial cancer with organ preservation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2104. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badylak S.F. The extracellular matrix as a scaffold for tissue reconstruction. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:377. doi: 10.1016/s1084952102000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellaro T.L. Ravindra A.K. Stolz D.B. Badylak S.F. Maintenance of hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cell phenotype in vitro using organ-specific extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2301. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zantop T. Gilbert T.W. Yoder M.C. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix scaffolds are repopulated by bone marrow-derived cells in a mouse model of achilles tendon reconstruction. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1299. doi: 10.1002/jor.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badylak S.F. Park K. Peppas N. McCabe G. Yoder M. Marrow-derived cells populate scaffolds composed of xenogeneic extracellular matrix. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:1310. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00729-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melman L. Jenkins E.D. Hamilton N.A. Bender L.C. Brodt M.D. Deeken C.R., et al. Early biocompatibility of crosslinked and non-crosslinked biologic meshes in a porcine model of ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2011;15:157. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0770-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentin J.E. Stewart-Akers A.M. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Macrophage participation in the degradation and remodeling of extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1687. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valentin J.E. Badylak J.S. McCabe G.P. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix bioscaffolds for orthopaedic applications. A comparative histologic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2673. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710. doi: 10.1038/nri1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore A.J. Beazley W.D. Bibby M.C. Devine D.A. Antimicrobial activity of cecropins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:1077. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.6.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore A.J. Devine D.A. Bibby M.C. Preliminary experimental anticancer activity of cecropins. Pept Res. 1994;7:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berkowitz B.A. Bevins C.L. Zasloff M.A. Magainins: a new family of membrane-active host defense peptides. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:625. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90138-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li F. Li W. Johnson S. Ingram D. Yoder M. Badylak S. Low-molecular-weight peptides derived from extracellular matrix as chemoattractants for primary endothelial cells. Endothelium. 2004;11:199. doi: 10.1080/10623320490512390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis G.E. Bayless K.J. Davis M.J. Meininger G.A. Regulation of tissue injury responses by the exposure of matricryptic sites within extracellular matrix molecules. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1489. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65020-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agrawal V. Brown B.N. Beattie A.J. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Evidence of innervation following extracellular matrix scaffold-mediated remodelling of muscular tissues. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2009;3:590. doi: 10.1002/term.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brennan E.P. Tang X.H. Stewart-Akers A.M. Gudas L.J. Badylak S.F. Chemoattractant activity of degradation products of fetal and adult skin extracellular matrix for keratinocyte progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2008;2:491. doi: 10.1002/term.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crisan M. Yap S. Casteilla L. Chen C.W. Corselli M. Park T.S., et al. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reing J.E. Zhang L. Myers-Irvin J. Cordero K.E. Freytes D.O. Heber-Katz E., et al. Degradation products of extracellular matrix affect cell migration and proliferation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:605. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agrawal V. Johnson S.A. Reing J. Zhang L. Tottey S. Wang G., et al. Epimorphic regeneration approach to tissue replacement in adult mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tottey S. Corselli M. Jeffries E.M. Londono R. Peault B. Badylak S.F. Extracellular matrix degradation products and low-oxygen conditions enhance the regenerative potential of perivascular stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:37. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freytes D.O. Badylak S.F. Webster T.J. Geddes L.A. Rundell A.E. Biaxial strength of multilaminated extracellular matrix scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2353. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aksu A.E. Rubin J.P. Dudas J.R. Marra K.G. Role of gender and anatomical region on induction of osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;60:306. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3180621ff0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schotte O.E. Smith C.B. Wound healing processes in amputated mouse digits. Biol Bull. 1959;117:546. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hans F. Dimitrov S. Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene. 2001;20:3021. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barth D. Kyrieleis O. Frank S. Renner C. Moroder L. The role of cystine knots in collagen folding and stability, part II. Conformational properties of (Pro-Hyp-Gly)n model trimers with N- and C-terminal collagen type III cystine knots. Chemistry. 2003;9:3703. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitahara T. Takeishi Y. Arimoto T. Niizeki T. Koyama Y. Sasaki T., et al. Serum carboxy-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen (ICTP) predicts cardiac events in chronic heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function. Circ J. 2007;71:929. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banfi G. Lombardi G. Colombini A. Lippi G. Bone metabolism markers in sports medicine. Sports Med. 2010;40:697. doi: 10.2165/11533090-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kanoupakis E.M. Manios E.G. Kallergis E.M. Mavrakis H.E. Goudis C.A. Saloustros I.G., et al. Serum markers of collagen turnover predict future shocks in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients with dilated cardiomyopathy on optimal treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2753. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Reilly M.S. Boehm T. Shing Y. Fukai N. Vasios G. Lane W.S., et al. Endostatin: an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cell. 1997;88:277. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramchandran R. Dhanabal M. Volk R. Waterman M.J. Segal M. Lu H., et al. Antiangiogenic activity of restin, NC10 domain of human collagen XV: comparison to endostatin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255:735. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colorado P.C. Torre A. Kamphaus G. Maeshima Y. Hopfer H. Takahashi K., et al. Anti-angiogenic cues from vascular basement membrane collagen. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beattie A.J. Gilbert T.W. Guyot J.P. Yates A.J. Badylak S.F. Chemoattraction of progenitor cells by remodeling extracellular matrix scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1119. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kragl M. Knapp D. Nacu E. Khattak S. Maden M. Epperlein H.H., et al. Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration. Nature. 2009;460:60. doi: 10.1038/nature08152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar A. Godwin J.W. Gates P.B. Garza-Garcia A.A. Brockes J.P. Molecular basis for the nerve dependence of limb regeneration in an adult vertebrate. Science. 2007;318:772. doi: 10.1126/science.1147710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monaghan J.R. Epp L.G. Putta S. Page R.B. Walker J.A. Beachy C.K., et al. Microarray and cDNA sequence analysis of transcription during nerve-dependent limb regeneration. BMC Biol. 2009;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee C.H. Cook J.L. Mendelson A. Moioli E.K. Yao H. Mao J.J. Regeneration of the articular surface of the rabbit synovial joint by cell homing: a proof of concept study. Lancet. 2010;376:440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60668-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim J.Y. Xin X. Moioli E.K. Chung J. Lee C.H. Chen M., et al. Regeneration of Dental-Pulp-like Tissue by Chemotaxis-Induced Cell Homing. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3023. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis J.P. Trobaugh F.E., Jr Haematopoietic Stem Cells. Nature. 1964;204:589. doi: 10.1038/204589a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lagasse E. Connors H. Al-Dhalimy M. Reitsma M. Dohse M. Osborne L., et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:1229. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barker N. van Es J.H. Kuipers J. Kujala P. van den Born M. Cozijnsen M., et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davis N.F. Callanan A. McGuire B.B. Mooney R. Flood H.D. McGloughlin T.M. Porcine extracellular matrix scaffolds in reconstructive urology: An ex vivo comparative study of their biomechanical properties. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2011;4:375. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Medberry C.J. Tottey S. Jiang H. Johnson S.A. Badylak S.F. Resistance to infection of five different materials in a rat body wall model. J Surg Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jjs.2010.08.035. [Epub ahead of print]; PMID: 20888581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boruch A.V. Nieponice A. Qureshi I.R. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Constructive remodeling of biologic scaffolds is dependent on early exposure to physiologic bladder filling in a canine partial cystectomy model. J Surg Res. 2010;161:217. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parekh A. Mantle B. Banks J. Swarts J.D. Badylak S.F. Dohar J.E., et al. Repair of the tympanic membrane with urinary bladder matrix. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1206. doi: 10.1002/lary.20233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilbert T.W. Gilbert S. Madden M. Reynolds S.D. Badylak S.F. Morphologic assessment of extracellular matrix scaffolds for patch tracheoplasty in a canine model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:967. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.071. discussion 974, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly D.J. Rosen A.B. Schuldt A.J. Kochupura P.V. Doronin S.V. Potapova I.A., et al. Increased myocyte content and mechanical function within a tissue-engineered myocardial patch following implantation. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2189. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kochupura P.V. Azeloglu E.U. Kelly D.J. Doronin S.V. Badylak S.F. Krukenkamp I.B., et al. Tissue-engineered myocardial patch derived from extracellular matrix provides regional mechanical function. Circulation. 2005;112:I144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nieponice A. McGrath K. Qureshi I. Beckman E.J. Luketich J.D. Gilbert T.W., et al. An extracellular matrix scaffold for esophageal stricture prevention after circumferential EMR. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:289. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nieponice A. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. Reinforcement of esophageal anastomoses with an extracellular matrix scaffold in a canine model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:2050. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Badylak S.F. Vorp D.A. Spievack A.R. Simmons-Byrd A. Hanke J. Freytes D.O., et al. Esophageal reconstruction with ECM and muscle tissue in a dog model. J Surg Res. 2005;128:87. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crapo P.M. Gilbert T.W. Badylak S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3233. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]