Abstract

Biomaterials are native or synthetic polymers that act as carriers for drug delivery or scaffolds for tissue regeneration. When implanted in vivo, biomaterials should be nontoxic and exert intended functions. For tooth regeneration, biomaterials have primarily served as a scaffold for (1) transplanted stem cells and/or (2) recruitment of endogenous stem cells. This article critically synthesizes our knowledge of biomaterial use in tooth regeneration, including the selection of native and/or synthetic polymers, three-dimensional scaffold fabrication, stem cell transplantation, and stem cell homing. A tooth is a complex biological organ. Tooth loss represents the most common organ failure. Tooth regeneration encompasses not only regrowth of an entire tooth as an organ, but also biological restoration of individual components of the tooth including enamel, dentin, cementum, or dental pulp. Regeneration of tooth root represents perhaps more near-term opportunities than the regeneration of the whole tooth. In the adult, a tooth owes its biological vitality, arguably more, to the root than the crown. Biomaterials are indispensible for the regeneration of tooth root, tooth crown, dental pulp, or an entire tooth.

Introduction

Tooth loss results from dental caries, periodontal disease, trauma, congenital anomalies, or chronic diseases. For many wildlife species, complete tooth loss may well equate to the end of life. In humans, tooth loss can lead to physical and mental suffering that compromises an individual's self-esteem and quality of life.1 A tooth is a complex biological organ. Dental caries, also known as tooth decay or cavity, is an infectious disease caused primarily by bacterial colonies that break down hard tissues of the tooth such as enamel and dentin, as well as soft tissue of the tooth known as dental pulp. Periodontal disease is another highly prevalent disease in humans and also a major cause for tooth loss.2–5 Dental caries is one of the most common disorders in humans, second only to common cold. Tooth loss represents the most common organ failure in humans. Americans make about 500 million dental visits each year. In 2009, about $102 billion was spent on dental services in the United States. According to the Center for Disease Control, one in two Americans is affected by tooth decay by age 15. By age 20, roughly one in four teeth are decayed or filled in the United States. By age 60, more than 60% of the teeth and more than 90% of the Americans are affected by dental caries. In humans, tooth loss is replaced with artificial prosthesis such as dental implants. Despite reported clinical success, dental implant failure is well documented in the literature including peri-implant bone loss, infections, and allergic reactions. The fundamental cause of dental implant failure is that metallic implants cannot remodel with host alveolar bone which undergoes physiologically necessary remodeling over time.

Tooth regeneration has long been the dental profession's aspiration. However, it was not until the recent past that experimental approaches for tooth regeneration have been made possible by advances in cell biology and bioengineering. Cells are the building blocks of multiple tissues in a tooth organ, including ameloblasts that form the enamel, odontoblasts that form dentin, cementoblasts that form the cementum, and cells of multiple lineages including mesenchymal, fibroblastic, vascular, and neural cells that form dental pulp. Collectively, enamel, dentin, cementum, and dental pulp form a tooth or tooth organ. Tooth regeneration encompasses not only regrowth of an entire tooth as an organ, but also biological restoration of individual components of the tooth including enamel, dentin, cementum, or dental pulp. However, a tooth cannot function unless it is connected to and supported by the periodontium that includes the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. Biological scaffolds provide anatomic dimensions of temporary matrices in which cells synthesize tissues and, therefore, play important, if not indispensible, roles in tooth regeneration. Scaffolds provide biophysical support for cell recruitment, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and/or metabolism. The primary objective of this review is to synthesize existing literature in the design, fabrication, and application of biological scaffolds in tooth regeneration.

Regeneration of teeth can be divided into several specific areas as follows:

• Regeneration or de novo formation of an entire, anatomically correct tooth6;

• Regeneration of the root7;

• Regeneration of dentin that may either act as reparative dentin to seal off an exposed pulp chamber or as a replacement of current synthetic materials11–14;

• Regeneration of cementum as a part of periodontium regeneration or for loss of cementum and/or dentin resulting from orthodontic tooth movement15,16;

• Regeneration of periodontium including cementum, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone17–19;

• Regeneration or synthesis of enamel-like structures that may be used as biological substitute for enamel20–22;

The native extracellular matrix of a tooth organ provides a scaffold for the recruitment, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism of a broad array of resident cells including odontoblasts, fibroblasts, vascular cells, and neural endings, in addition to stem/progenitor cells. In principle, biological scaffolds for the regeneration of tooth organ should allow the key functions of the native tooth organ. At a minimum, designed biological scaffolds for tooth regeneration should be biocompatible, nontoxic, and promote the regeneration of a single or multiple dental tissues.

Soft Biomaterials

Polymeric hydrogels can be native, synthetic, or hybrid.23–25 Native hydrogels are typically of biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and with the ability to undergo biocompatible breakdown in vivo. A major drawback of native hydrogels is limited supply. Synthetic hydrogels have the advantage of virtually unlimited supply and can be tailored to possess a broad range of structural, mechanical, and chemical properties. Biologically safe degradation is usually intrinsic with native hydrogels, and frequently one of the desirable properties of synthetic polymers.

Fibrin

Fibrin hydrogel is polymerized from purified allogeneic fibrinogen by purified thrombin.26 Fibrin has been widely used as scaffolds in the regeneration of cardiovascular tissue,27 bone,28 neural tissues,29 cartilage,30 and others. Fibrin hydrogel has several advantages such as controllable degradation rate, low immunogenicity, and allow relatively homogenous cell distribution on cell seeding and polymerization.27 However, fibrin undergoes shrinkage and has low mechanical stiffness.27,31 Fixing agents such as poly-l-lysine can reduce shrinkage.27 Greater fibrinogen concentrations can increase fibrin's mechanical properties, although cell survival and spread are compromised.32 Fibrin's intrinsic mechanical properties are modest but can be enhanced by polyurethane, β-tricalciumphosphate (β-TCP)/polyethylene.33,34

Collagen

Collagen is a major macromolecule of the extracellular matrix and exists ubiquitously in diverse tissues such as bone, teeth, skin, cartilage, tendon, and ligament.35,36 Collagen type I is frequently extracted and used as a scaffold in tissue engineering.37–39 Allogeneic collagen, such as bovine collagen sponge or bovine collagen gel, has excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity in humans.37–39 A major drawback of collagen scaffold is its modest physical strength,36 although it appears to be sufficient for dental pulp regeneration.36 Chemical cross-linking by the addition of cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde or diphenylphosphoryl azide can enhance the mechanical stiffness of collagen scaffolds.40,41 However, cross-linking agents can compromise cell survival and biocompatibility.36 Similar to fibrin, collagen's mechanical properties can be enhanced by forming hybrid scaffolds with β-TCP/polyethylene42 and hydroxyapatite.43

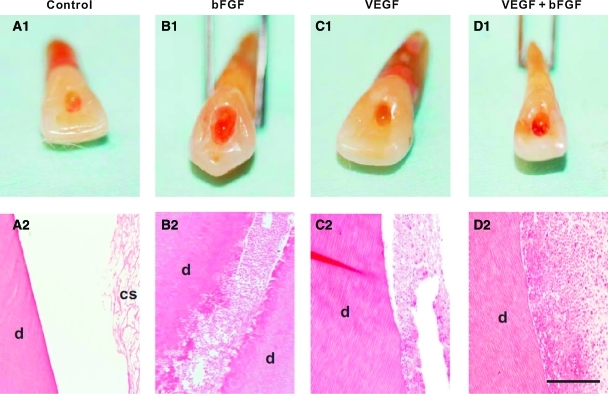

Collagen scaffolds loaded with a series of growth factors have been implanted in endodontically treated root canals. On in vivo implantation of endodontically treated human teeth in mouse dorsum for the tested 3 or 6 weeks, delivery of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and/or vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) yields re-cellularized and revascularized connective tissue that integrates to the native dentinal wall in root canals9 (Fig. 1). Similarly, delivery of collagen scaffolds with dental pulp stem cells and dentin matrix protein-1 in tooth slices in mice leads to ectopic formation of dental pulp-like tissue.10

FIG. 1.

Regeneration of dental-pulp-like tissues in human teeth.9 Root canals of endodontically treated human teeth were filled with collage sponges with or without delivery of bFGF and/or VEGF followed by 3-week in vivo implantation. Endodontically treated root canals with collagen sponge alone showed pale access opening A1, and residual collagen scaffold (cs) on microscopic section (A2), adjacent to native dentin (d). (B1) bFGF delivery yielded red pigmentation and re-cellularization of endodontically treated root canal with abundant cells and some extracellular matrix that integrated with the wall of native dentin (d) (B2). VEGF delivery also showed red pigmentation in root apex (C1) and yielded re-cellularization in the root canal (C2). Combined bFGF and VEGF delivery also generated red pigmentation (D1) and abundant cells within root canal (D2). Scale A2, B2, C2, and D2: 500 μm. bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a primary extracellular component of connective tissue and plays an important role in wound healing. The HA is biocompatible and has low immunogenicity.44,45 The HA hydrogel has been exploited in the regeneration of bone,46 cartilage,47 vocal cord,48 and brain.49 A potential disadvantage of HA hydrogel is its poor mechanical strength and rapid in vivo degradation rate.48 Accordingly, HA hydrogel can be chemically modified by the carboxylic acid groups such as esterification50 or methacrylamide,51 or the alcohol groups modified by divinyl sulfone,52 diglycidyl ether, or poly(ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether.53 The HA hydrogel can also be crosslinked with dialdehyde,54 dihydrazide,55 or disulfide.56 The attachment, spreading, and proliferation of cells in HA hydrogel can be enhanced with arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptides.57,58 The HA hydrogel can also be modified with biotin for probing HA-receptor interactions.57,58

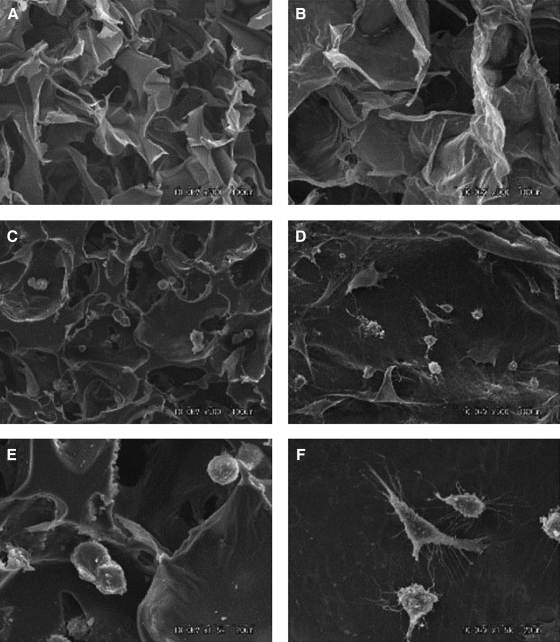

The HA hydrogels have also been widely investigated for applications in tissue regeneration, but their application in dental pulp regeneration is limited.59 An injectable hydrogel, over pre-shaped hydrogel (e.g., by molding), is often clinically preferable, because pulp chamber and root canal have irregular shape. The odontoblastic cell line (KN-3 cells) readily adheres to both HA or collagen sponges in vitro (Fig. 2). Expression of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α by KN-3 cells seeded in a HA sponge is virtually the same as in collagen sponge. When HA and collagen sponges are implanted in amputated dental pulp of rat molars in vivo, the numbers of granulated leukocytes invaded into HA sponge from amputated dental pulp are significantly lower than those in collagen sponge,59 suggesting that HA sponge has an appropriate structure, biocompatibility, and biodegradation for use as a scaffold for dental pulp regeneration.59

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron microphotographs of HA (A, C, E) and collagen (B, D, F) sponges with and without KN-3 cells. HA sponge was fabricated from a photocrosslinkable HA derivative, which was conjugated cinnamic acid into the carboxyl of HA (900 kDa) from rooster combs using aminopropanol. Briefly, the HA derivative was dissolved in water at a concentration of 4.0 wt%, then the solution was poured into a mold, and exposed to ultraviolet light (280 nm, 20 J/cm2) at −20°C for 15 min. The reaction was based on the dimmer formation of cinnamic acid molecules, and each of the HA chain was cross-linked and formed into three-dimensional net link structure. Collagen sponge was fabricated using a conventional freeze-drying method, followed by dehydrothermal cross-linking. Briefly, an aqueous solution of porcine tendon type collagen was prepared by pepsin treatment (3 mg/mL, pH 3.0) in HCl whipped in a homogenizer at 8000 rpm for 15 min with cooling on ice, then poured into plastic molds, and immediately after being frozen to −80°C, freeze-dried. The freeze-dried sponges were treated in a vacuum at 140°C for 12 h at 0.1 Torr vacuum, and sterilized with ethylene oxide gas at 40°C before use in the experiments. (A, B) Dry sponges showing porous structures. Original magnification, ×500; (C, D) Sponges seeded with KN-3 cells. Original magnification, ×500; (E, F) Higher magnification (×1500) of C and D, respectively. HA, hyaluronic acid.

Poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogel

Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) is a nontoxic, water soluble, and biocompatible polymer. PEG has low immunogenicity and can undergo in vivo degradation. PEG is generally resistant to cell and protein adsorption, and has been widely explored as a drug delivery carrier.60 Recently, PEG hydrogel has been explored as a scaffold material for tissue regeneration,61,62 including de novo formation of a structure in the shape of a temporomandibular joint regeneration.61,62 Compared with native hydrogels, PEG has several advantages such as the ability for photopolymerization, easy control of scaffold structure, and chemical composites. Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), a chemical modification of PEG, is formed by the substitute of terminal hydroxyl groups with acrylates.63 PEGDA can be crosslinked by a variety of methods.64 The mechanical strength of PEG hydrogel depends on the molecular weight, cross-linking, and concentration. The elastic modulus can be enhanced by reducing the molecular weight or increasing polymer concentration.65–67 The permeability and mesh size of PEGDA are determined by molecular weight and concentration.68

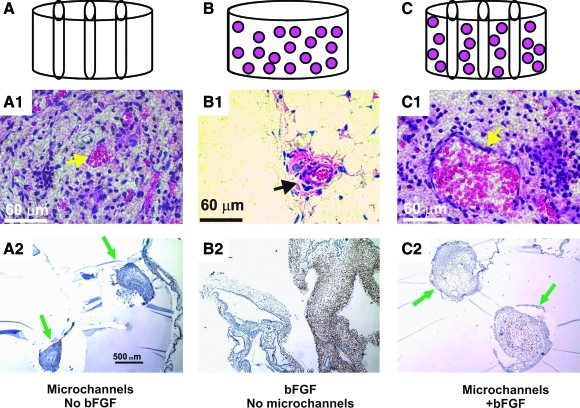

Vascularization is pivotal for tissue regeneration. In an in vivo investigation, biophysical and/or biochemical approaches are combined to induce neovascularization in PEGDA hydrogel.69 Hydrogel cylinders are fabricated from PEGDA in four configurations: PEG alone, PEG with bFGF, microchanneled PEG alone, or both bFGF-adsorbed and microchanneled PEG (Fig. 3A–C). In vivo implantation reveals no neovascularization in unmodified PEG, but substantial angiogenesis in bFGF-adsorbed and/or microchanneled PEG. Strikingly, substantial angiogenesis is also present in microchanneled PEG without bFGF incorporation. The striking difference of neovascularization between unmodified PEG and microchanneled PEG suggests that microchannels provide a conduit for angiogenesis. Especially, engineered microchannels may provide a generic approach for modifying existing scaffolds by providing conduits for vascularization and/or cell metabolism. The separate or combined approaches to induce vascularization may be of relevance to dental pulp regeneration.

FIG. 3.

Induction of cellular ingrowth and angiogenesis in PEG hydrogel. After in vivo subcutaneous implantation in the dorsum of immunodeficient mice, the harvested PEG hydrogel samples showed distinct histological features. (A) PEG hydrogel molded into 64 mm (diameter×height) cylinder (without either bFGF or microchannels). (B) PEG hydrogel with three microchannels. (C) PEG hydrogel cylinder with micro-channels and adsorbed with both 0.5 mg/mL bFGF and three microchannels. (A1) PEG hydrogel with microchannels but without bFGF showed host tissue infiltration primarily in the lumen of microchannels, and scarcely in the rest of PEG hydrogel. The infiltrating host tissue includes erythrocyte-filled blood vessels that are lined by endothelial cells (arrow). (A2) VEGF was immunolocalized only to host-derived tissue within the lumen of microchannels, indicating the vascular nature of the infiltrating host tissue. Arrows point to microchannels and the infiltrating host tissue. (B1) PEG hydrogel with bFGF but without microchannels showed apparently random and isolated islands of infiltrating host tissue (arrow). The infiltrating host tissue includes vascular structures with erythrocyte-filled blood vessels that are lined by endothelial cells (arrow). (B2) VEGF was immunolocalized to host-derived tissue within PEG hydrogel (without microchannels). (C1) PEG hydrogel with both microchannels and bFGF showed host tissue infiltration only in the lumen of microchannels, but scarcely in the rest of the PEG hydrogel. The infiltrating host tissue includes vascular structures with erythrocyte-filled blood vessels that are lined by endothelial cells (arrow). (C2) VEGF was immunolocalized only to host-derived tissue within the lumen of microchannels. Arrows point to ingrowing blood vessels and adjunct soft tissue within microchannels. PEG, poly(ethylene glycol). Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

Alginate

Alginate is a naturally derived polysaccharide and has been widely used as a scaffolding material in tissue regeneration. Alginate is nontoxic, biocompatible, and permeable to small molecular-weight proteins.70 However, alginate has several drawbacks including low mechanical stiffness and difficulty to control in vivo degradation rate. Alginate prepared with ionic cross-linking has weak mechanical stiffness,71 although its mechanical strength can be improved by increasing calcium content and cross-linking density.72 Compared with ionic crosslinking, stable covalent cross-linked alginate hydrogels have greater mechanical strength and swelling ratio.73 γ-irradiation is a reliable and straightforward approach for the generation of a stable alginate hydrogels.74 To address the issue of nonspecific cellular interactive property, the RGD modified alginate hydrogel promotes cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation, and differentiation.75,76

Alginate hydrogel has been loaded with exogenous transforming growth factor TGFβ1 for the regeneration of the dentin-pulp complex.77 Both TGFβ1-containing and acid-treated alginate hydrogels, but not untreated alginate hydrogel, promote dentin matrix secretion and odontoblast-like cell differentiation with subsequent secretion of tubular dentin matrix (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

In vitro dentin repair model. (A) Increased pre-dentin width after 50 ng TGF-β1 delivery indicating upregulation of matrix secretion; original magnification ×400. (B) Lack of matrix upregulation with hydrogel containing TGF-β1 antibodies; original magnification ×400. (C) De novo dentinogenesis showing deposition of regular tubular dentin lined by associated cells (tooth slice cultured with alginate hydrogel containing 100 ng TGF- β1); original magnification ×630. (D) High-power view of slice from part C showing interface between cut pulpal surface and new dentin matrix and associated cells, which display a low columnar, polarized morphology; original magnification ×1640. (E) Deposition of new regular tubular dentin matrix to the existing dentin matrix of the tooth slice (tooth slice cultured with alginate hydrogel containing 100 ng TGF-β1), original magnification ×400. (F) Tooth slice cultured with untreated alginate hydrogel showing absence of de novo dentinogenesis along the cut pulpal surface; original magnification ×400. TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1.

Agarose

Agarose derives from seaweed and forms thermally reversible gels.36 Agarose has been exploited for drug delivery due to advantages such as easy-gelling, thermo-reversibility, and injectability.78–80 Agarose lacks native ligands in mammalian cells.81 Incorporation of CDPGYIGSR peptides in agarose allows neurite outgrowth from dorsal root ganglion.82,83 Agarose hydrogels accommodate three-dimensional (3D) neurite extension from primary sensory ganglia in vitro.82 The rate of neurite extension is inversely correlated to the mechanical stiffness of agarose gels in the range of 0.75%–2.00% (wt/vol) gel concentrations.

Stiff Biomaterials

Mechanically stiff biomaterials can provide mechanical and structural substitutes in tooth regeneration and accommodate cellular functions. Cells are typically seeded and adhere to the porous surface of mechanically stiff scaffolds. In comparison, cells are typically seeded in the aqueous phase of soft biomaterials, followed by polymerization for encapsulation.

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) is broadly used in drug delivery due to its general biocompatibiltiy and low toxicity.84,85 However, PLGA can be hydrophobic and may yield acidic degradation products.86 PLGA micro/nanoparticles are associated with harsh fabrication processes.86 Accordingly, a variety of thermogelling block copolymers have been synthesized including diblock, triblock, and multiblock. Also, a block copolymer of PLGA and PEG is created as degradable thermo-sensitive hydrogels.87 PEG-PLGA copolymer hydrogel has a number of advantages including injectability and minimal immune response as a drug delivery carrier with controlled release rate, as well as gene delivery.84,88,89 PLGA-PEG-PLGA triblock copolymer enhances gene transfection efficacy and promotes wound healing.90,91 Figure 5 shows an injectable composite consisting of poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) and polyethylene glycol dissolved in polyethylene glycol by heat treatment.92 Subsequently, this PLGA hydrogel was applied with recombinant human growth differentiation factor-5 (rhGDF-5) in periodontal defects in a dog model.93 Periodontal pockets (3×6 mm, width×depth) are surgically created over the buccal roots of the second and fourth mandibular premolars in mongrel dogs. There is progressive bone maturation with lamellar bone formation at 6 weeks on rhGDF-5/PLGA delivery (Fig. 6).

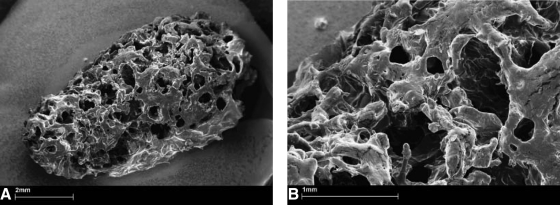

FIG. 5.

Scanning electron microscopy photomicrographs of the macroporous PLGA composite after a 2-h incubation at 37°C in phosphate-buffered saline and drying. The injectable composite consists of poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (20.0 wt%; PLGA Resomer® RG502H) and polyethylene glycol 1500 (2.0 wt%) dissolved in polyethylene glycol 300 (47.0 wt%) by heat treatment. Calcium sulphate (15.0 wt%), d(−)-mannitol (13.0 wt%), and cellulose ether (3.0 wt%) were dispersed in the polymeric solution. The injectable PLGA composite was mixed with lyophilized rhGDF-5 before administration. (A) Overview of the coherent sponge-like structure with inter-connected macropores. (B) Smaller micropores less than 1000 μm integrated into the walls of the macropores are shown. PLGA, poly(lactide-co-glycolide); rhGDF-5, recombinant human growth differentiation factor-5.

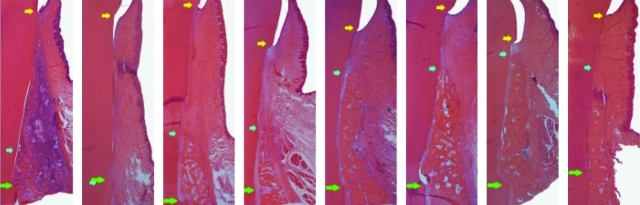

FIG. 6.

Representative photomicrographs of experimental pre-molar sites implanted with rhGDF-5/PLGA construct or serving as sham-surgery control at 2 (left), 4 (left centre), 6 (right centre), and 8 (right) weeks postsurgery. The left photomicrograph in each pair represents the rhGDF-5/PLGA construct. An inflammatory reaction likely assorted with biodegradation of the rhGDF-5/PLGA construct can be seen at 2 weeks. Generally, there are no other appreciable differences between the premolar site pairs. Green arrows represent the apical extension of the defects, blue arrows represent the coronal extension of newly formed alveolar bone, and the yellow arrows represent the location of the cemento-enamel junction. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

Polycaprolactone

Polycaprolactone (PCL) is a versatile synthetic polymer and has been used as a scaffold in tissue engineering.94,95 PCL is approved as a suture material and a drug delivery device by the United States Food and Drug Administration. PCL has limited bioactivity and may be susceptible to bacterial-mediated degradation.96 Surface properties of PCL can be modified, for example, by coating with hydroxyapatite to promote the adhesion and proliferation of endothelial cells, as hydroxyapatite increases surface wettability and roughness.97 PCL coated with gelatin and calcium phosphate promotes osteoblast adhesion, spreading, and proliferation.98 Composite scaffold of PCL and TCP nanoparticles has specific properties such as mechanical properties, wettability, porosity, and biodegradation rate distribution.99 Moreover, PCL nanofiber scaffold modified with collagen type I and III not only influences cell attachment, migration, and proliferation, but it also provides mechanical integrity for 3D vessel formation in vitro.100

Hydroxyapatite

Hydroxyapatite has been widely used in bone regeneration, owing to its biocompatibility, immune tolerance, and osteoconductivity. Hydroxyapatite is typically fabricated as a dense material. Porous hydroxyapatite is useful for bone regeneration, because it can be fabricated with 3D architecture similar to the trabecular bone.101 The performance of the porous hydroxyapatite scaffold is dictated by internal architecture including pore size, porosity, and interconnections.102 Internal architecture of hydroxyapatite can be created by several approaches including freeze casting,103 gel casting technique,104 and polymer sponge method.105 One of the major drawbacks of hydroxyapatite is its brittleness that limits its applications as a replacement of highly load-bearing bone.

Bioceramics

Bioceramics refers to a group of bioactive glasses and calcium phosphate ceramics. Bioceramics are biocompatible and have been widely used in reconstructive, orthopedic, maxillofacial, and craniofacial applications. Bioceramics can be fabricated via several approaches including phase-mixing,106 gas foaming,107soluble or volatile poragen processing,108,109 template casting,110 and solid freeform fabrication.111 Bioceramics can be fabricated with specific internal architecture and surface properties that accommodate cell distribution, adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation due to its porosity.112–114 Bioceramics have been loaded with osteogenic factors such as recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) to induce bone formation.115As with other materials such as PCL and HA, increases in porosity and pore size may compromise mechanical stiffness, and vice versa.116–119

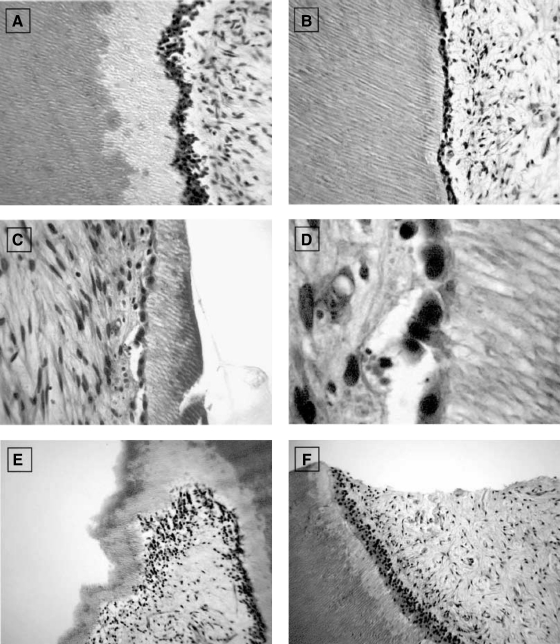

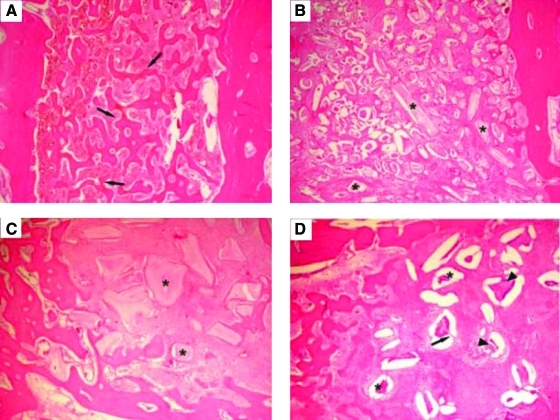

In order to evaluate soft and hard tissue reactions to two different hydroxyapatites and compared with bioglass, hydroxyapatite (synthetic hydroxyapatite and natural hydroxyapatite) and bioactive glass are implanted into tooth extraction sockets.120 The first and third upper and lower premolars, on both sides, are extracted in six female dogs. The extraction sockets are randomly assigned to four groups: Group 1: control (unfilled); Group 2: filled with synthetic hydroxyapatite; Group 3: filled with bovine bone mineral (natural hydroxyapatite); and Group 4: filled with bioactive glass. The animals are euthanized at 4, 8, and 28 weeks after extraction. Most particles of synthetic hydroxyapatite have bone formation on their surface, although some particles show a layer of fibrous connective tissue. The bovine bone mineral group shows particles partially replaced with bone formation. The bioactive glass group shows particles with a thin layer of calcified tissue, suggesting complete resorption (Fig. 7).120

FIG. 7.

Photomicrographs at 4 weeks: (A) Group 1 (control site): The majority of the extraction socket was filled with newly formed bone (arrows). (B) Group 2 (synthetic hydroxyapatite site): Specimens showed particles of biomaterials (*) involved by connective tissue. (C) Group 3 (bovine bone mineral site): Particles of biomaterials (*) were involved by connective fibrous tissue. (D) Group 4 (bioactive glass site): Extraction sockets exhibited newly formed bone with particles of biomaterials (*). Granules of biomaterials showed fissures (arrows) with cell infiltration (arrowheads). Hematoxylin and eosin stain; original magnification ×60. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/teb

Tooth Regeneration: Cell Transplantation Versus by Cell Homing

Existing literature on tooth regeneration has taken two distinctive approaches: cell transplantation and cell homing. Cell transplantation has been the predominant approach in tooth regeneration. Disassociated cells of porcine or rat tooth buds in biomaterials yielded putative dentin and enamel organ.121,122 Tooth bud cells and bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells in collagen, PLGA, or silk-protein scaffolds induced putative tooth-like tissues, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament.123–125 Embryonic oral epithelium and adult mesenchyme together up-regulate odontogenesis genes on mutual induction and yielded dental structures on transplantation into adult renal capsules or jaw bone.126 Similarly, implantation of E14.5 rat molar rudiments into adult mouse maxilla produced tooth-like structures with surrounding bone.127,128 Multipotent cells of the tooth apical papilla in TCP in swine incisor extraction sockets generated soft and mineralized tissues resembling the periodontal ligament.129 E14.5 oral epithelium and dental mesenchyme were reconstituted in collagen gels and cultured ex vivo,130 and when implanted into the maxillary molar extraction sockets in 5-week-old mice, tooth morphogenesis took place and was followed by eruption into occlusion.131 Several studies have begun to tackle an obligatory task of scale up toward human tooth size.132,133

Tooth regeneration by cell transplantation is a meritorious approach. However, there are hurdles in the translation of cell-delivery-based tooth regeneration into therapeutics. Autologous embryonic tooth germ cells are inaccessible for human applications.128,130,131 Xenogenic embryonic tooth germ cells (from non-human species) may elicit immunorejection and tooth dysmorphogenesis. Autologous postnatal tooth germ cells (e.g., third molars) or autologous dental pulp stem cells are of limited availability. Regardless of cell source, cell delivery for tooth regeneration, similar to cell-based therapies for other tissues, encounters translational barriers.134 Excessive cost of commercialization and difficulties in regulatory approval have not precluded, to date, any significant clinical translation of tooth regeneration.

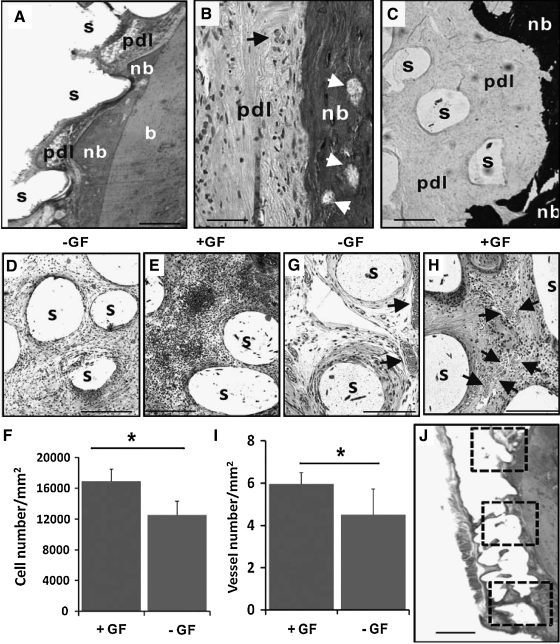

The dimensions of the permanent mandibular first molar are fabricated via 3D layer-by-layer apposition.61,135 The composite consists of PCL and hydroxyapatite. A blended cocktail of SDF1 and BMP7 is loaded in collagen gel and infused in scaffold's microchannels. On in vivo implantation, multiple tissues are formed de novo with structures reminiscent of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. Mineralized tissues were formed in microchannels of human molar-shaped scaffolds. Quantitatively, significantly more cells are recruited into the microchannels of the human molar scaffolds on combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery than without growth-factor delivery.6 Angiogenesis has taken place in microchannels with growth-factor delivery. Combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery elaborates significantly more blood vessels than without growth-factor delivery.6 Scaffolds in the shape of the rat mandibular incisor integrated with surrounding tissue, thus showing tissue ingrowth into the scaffolds' microchannels. New bone formation takes place on combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery that integrates the scaffold and existing alveolar bone (Fig. 8). Angiogenesis takes place in the scaffolds' microchannels with growth-factor delivery. Quantitatively, combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery elaborates significantly more blood vessels than the growth-factor-free group (Fig. 8).6

FIG. 8.

Orthotopic regeneration of tooth-like structures in vivo. (A) The rat mandibular incisor scaffold integrated with surrounding tissue, showing tissue ingrowth of multiple tissue phenotypes, including the native alveolar bone (b), newly formed bone (nb), and a putative periodontal ligament (pdl). The newly formed bone (nb) showed ingrowth into microchannel openings and inter-staggered with scaffold microstrands (s). (B) Newly formed bone (nb) has bone marrow (arrows) and embedded osteocyte-like cells, immediately adjacent to a putative periodontal ligament (pdl) consisting of fibroblast-like cells and collagen buddle-like structures. (C). Newly formed bone (nb) is well-mineralized (von Kossa preparation), in contrast to the adjacent unmineralized, putative periodontal ligament (pdl). (D) Cells populated the scaffold's microchannels even without growth-factor delivery, but are more abundant with SDF1 and BMP7 delivery (E). (F) Combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery recruited significantly more cells than without growth-factor delivery. Angiogenesis took place in scaffolds' microchannels without growth-factor delivery (G), but was more substantial with growth-factor delivery (H). Arrows indicate blood vessels. *, p<0.05. (I) Combined SDF1 and BMP7 delivery induced significantly more blood vessels than without growth-factor delivery. (J) The numbers of recruited cells and blood vessels were quantified from three different locations along the entire root length of the rat mandibular incisor scaffold. Scale: 100 μm. GF, growth factor(s).

These findings are described in detail in6 and represent the first report of regeneration of anatomically shaped tooth-like structures in vivo, and by cell homing without cell delivery. The potency of cell homing is substantiated not only by cell recruitment into scaffold's microchannels, but also by regeneration of a putative periodontal ligament and newly formed alveolar bone.6 Tooth regeneration requires condensation of sufficient cells of multiple lineages.128,136 The observed putative periodontal ligament and newly formed alveolar bone suggest SDF1's and/or BMP7's ability to recruit multiple cell lineages. The SDF1 is chemotactic for bone marrow stem/progenitor cells and endothelial cells, both of which are critical for angiogenesis.137–139 The SDF1 binds to CXCR4, a chemokine receptor for endothelial cells and bone marrow stem/progenitor cells.137,140 Here, SDF1 likely has homed mesenchymal and endothelial stem/progenitor cells in native alveolar bone into porous tooth scaffolds in rat jaw bone, and connective tissue progenitor cells in dorsal subcutaneous tissue into human molar scaffold.141–143 BMP7 plays important roles in osteoblast differentiation and phosphorylation via SMAD pathways, which induces transcription of multiple osteogenic/odontogenic genes.144,145 Here, BMP7 likely is responsible for newly formed, mineralized alveolar bone in rat extraction socket and ectopic mineralization in human tooth scaffold implanted in the dorsum. Our ongoing work has identified additional growth factors that may constitute an optimal conglomerate for tooth regeneration. Cell homing is an under-recognized approach in tissue regeneration,146 and it offers an alternative to cell-delivery-based tooth regeneration. Omission of cell isolation and ex vivo cell manipulation may accelerate regulatory, commercialization, and clinical processes. The cost for tooth regeneration by cell homing is not anticipated to be nearly as excessive as for cell delivery. In this work,6 regeneration of a putative periodontal ligament and new bone that integrates with the native alveolar bone appears to provide the ground for a clinically translatable approach. The present work does not preclude parallel studies of tooth regeneration by cell transplantation. Our recent work continues to explore regeneration of multiple tissues by cell delivery.147,148 One of the pivotal issues in tooth regeneration is to devise economically viable approaches that are not cost-prohibitive and can translate into therapies for patients who cannot afford or are counter-indicated for dental implants. Cell-homing-based tooth regeneration may provide a tangible pathway toward clinical translation.

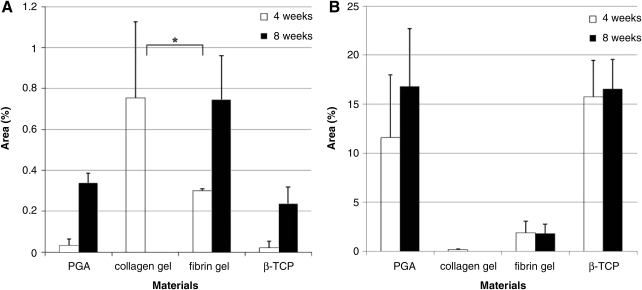

In another study, the effect of scaffolds on in vivo tooth regeneration is evaluated.149 Collagen and fibrin are selected based on the biocompatibility to dental papilla-derived cells, compared with those of polyglycolic acid (PGA) fiber and β-TCP porous block. Isolated porcine tooth germ-derived cells are seeded and implanted to the back of nude mice. Tooth bud-like structures are observed more frequently in collagen and fibrin gels than in PGA or β-TCP scaffolds, but the amount of hard tissue formation is less (Fig. 9). Thus, collagen and fibrin gel supports the initial regeneration process of tooth buds possibly by promoting functions of epithelial and mesenchymal cells. However, maturation of tooth buds is difficult in fibrin and collagen gels.149

FIG. 9.

Graph showing the percentages of epithelial cell area (A) and hard tissue area (B) in samples from four groups, 4 and 8 weeks after implantation. Percentages of epithelial cells were significantly higher in the collagen gel group (p<0.01) compared with that of the PGA group 4 weeks after transplantation. After 8 weeks, the samples in collagen gel had disappeared and only the samples from PGA, fibrin gel, and β-TCP groups were analyzed. The percentages of epithelial cells in the samples of the fibrin gel group were significantly higher than that in the PGA group at 8 weeks after transplantation (p<0.05). The percentages of hard tissue area were significantly lower in the fibrin gel at 4 weeks (p<0.05) and 8 weeks (p<0.01) and in the collagen gel at 4 weeks (p<0.05) compared with the PGA group. *Statistical significance. PGA, polyglycolic acid; β-TCP, β-tricalciumphosphate.

Biomaterial Selection for Tooth Regeneration

Biomaterials are likely indispensible for tooth regeneration. Soft biomaterials may serve as cell-encapsulating scaffolds, whereas mechanically stiff biomaterials scaffolds may serve as structural substitutes. Soft and mechanically stiff materials may be used together to complement each other's properties. When a kidney is bioengineered to function in humans, it probably does not matter what shape the tissue-engineered kidney is, as long as it functions similarly to a native kidney. However, a tooth should assume anatomic shape and dimensions in order to function in occlusion and in the dentition. The following are the general requirements of biomaterial scaffolds in tooth regeneration:

• Biocompatible, nontoxic, and ideally undergo biologically safe degradation.

• Provide encapsulation of cells or surface adhesion for cells that regenerate singular or multiple dental tissues.

• Allow functionality of at least some of the multiple cell types including ameloblasts, odontoblasts, cementoblasts, fibroblasts, vascular cells, and/or neural endings.

• Either native or synthetic polymers, or a hybrid, are valid choices as scaffolding materials for tooth regeneration, but multiple polymeric layers may be preferred in view of the diversity of tooth organs in structures and functions.

• Clinically applicable and offer a turn-key approach for clinicians. It can be readily sterilized, stored in a clinical setting, and has reasonable shelf life.

Tissue engineering was initiated with a concept of functional restoration of tissue or organ defects by the triad of cells, growth factors, and biomaterial scaffolds.150–152 The doctrine of cells, biomaterial scaffolds, and biological signals has been the guiding principle for tissue engineering. However, bioactive scaffolds may include those with embedded bioactive molecules and/or cells. The bioprinting approach as described above can “print” cells and/or molecules in 3D bioscaffolds.146 Both cell transplantation and cell homing are valid scientific approaches in tooth regeneration. Transplanted cells or delivered biomolecules and/or bioscaffolds can be infused in vivo to create a new environment that promote tooth regeneration. Biomolecules can be chemical compounds, peptides, proteins, or DNA/RNA. What is delivered in vivo is the means, whereas the best possible outcome of tooth regeneration is the end. Importantly, the cost of tooth regeneration therapy cannot be excessive for broad applications. Costly regenerative therapies are unlikely to be clinically viable. High-cost regenerative therapies for a patient with paralysis resulting from spinal cord injuries or stroke are likely justified and clinically applicable. However, expensive regenerative therapies for tooth regeneration, which do not treat life-threatening diseases, are not clinically viable. Costs for dental implant procedures are not modest and not affordable by numerous individuals in developing countries in which tooth loss is widespread. One of the challenges in front of us is to develop regenerative therapies that are less costly than dental implants and yet regenerate tooth components or an entire tooth. Biomaterials offer great potential for reduction in the cost of regenerative tooth therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank F. Guo and K. Hua for technical and administrative assistance. This work was supported by the NIH Grant 5RC2DE020767 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pihlstrom B.L. Michalowicz B.S. Johnson N.W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung S.H. Ryu J.I. Jung D.B. Association of total tooth loss with socio-behavioural health indicators in Korean elderly. J Oral Rehabil. 2011;38:517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polzer I. Schimmel M. Muller F. Biffar R. Edentulism as part of the general health problems of elderly adults. Int Dent J. 2010;60:143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonoki K. Takata Y. Ansai T. Fujisawa K. Fukuhara M. Wakisaka M., et al. Number of teeth and serum lipid peroxide in 85-year-olds. Community Dent Health. 2008;25:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ostberg A.L. Nyholm M. Gullberg B. Rastam L. Lindblad U. Tooth loss and obesity in a defined Swedish population. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:427. doi: 10.1177/1403494808099964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim K. Lee C.H. Kim B.K. Mao J.J. Anatomically Shaped Tooth and Periodontal Regeneration by Cell Homing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:842. doi: 10.1177/0022034510370803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonoyama W. Liu Y. Fang D. Yamaza T. Seo B.M. Zhang C., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohl K.S. Shon J. Rutherford B. Mooney D.J. Role of synthetic extracellular matrix in development of engineered dental pulp. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1998;9:749. doi: 10.1163/156856298x00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J.Y. Xin X. Moioli E.K. Chung J. Lee C.H. Chen M., et al. Regeneration of dental-pulp-like tissue by chemotaxis-induced cell homing. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:3023. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang G.T. Yamaza T. Shea L.D. Djouad F. Kuhn N.Z. Tuan R.S., et al. Stem/progenitor cell-mediated de novo regeneration of dental pulp with newly deposited continuous layer of dentin in an in vivo model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:605. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang G.T. Pulp and dentin tissue engineering and regeneration: current progress. Regen Med. 2009;4:697. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi S. Bartold P.M. Miura M. Seo B.M. Robey P.G. Gronthos S. The efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells to regenerate and repair dental structures. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2005;8:191. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2005.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thesleff I. Jarvinen E. Suomalainen M. Affecting tooth morphology and renewal by fine-tuning the signals mediating cell and tissue interactions. Novartis Found Symp. 284:142. doi: 10.1002/9780470319390.ch10. discussion 153, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub E.E. Role of matrix vesicles in biomineralization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1592. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeichner-David M. Regeneration of periodontal tissues: cementogenesis revisited. Periodontol 2000. 2006;41:196. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster B.L. Popowics T.E. Fong H.K. Somerman M.J. Advances in defining regulators of cementum development and periodontal regeneration. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:47. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke J.W. Sarment D.P. Whitesman L.A. Miller S.E. Jin Q. Lynch S.E., et al. Effect of rhPDGF-BB delivery on mediators of periodontal wound repair. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1441. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin N.H. Gronthos S. Mark Bartold P. Stem cells and future periodontal regeneration. Periodontol 2000. 2009;51:239. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellegrini G. Seol Y.J. Gruber R. Giannobile W.V. Pre-clinical models for oral and periodontal reconstructive therapies. J Dent Res. 2009;88:1065. doi: 10.1177/0022034509349748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Z. Sargeant T.D. Hulvat J.F. Mata A. Bringas P., Jr. Koh C.Y., et al. Bioactive nanofibers instruct cells to proliferate and differentiate during enamel regeneration. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1995. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer L.C. Newcomb C.J. Kaltz S.R. Spoerke E.D. Stupp S.I. Biomimetic systems for hydroxyapatite mineralization inspired by bone and enamel. Chem Rev. 2008;108:4754. doi: 10.1021/cr8004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J. Jiang D. Lin Q. Huang Z. Synthesis of dental enamel-like hydroxyapatite through solution mediated solid-state conversion. Langmuir. 2010;26:2989. doi: 10.1021/la9043649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim B.S. Mooney D.J. Development of biocompatible synthetic extracellular matrices for tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:224. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasseri B.A. Ogawa K. Vacanti J.P. Tissue engineering: an evolving 21st-century science to provide biologic replacement for reconstruction and transplantation. Surgery. 2001;130:781. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.112960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun G. Shen Y.I. Ho C.C. Kusuma S. Gerecht S. Functional groups affect physical and biological properties of dextran-based hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93:1080. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed T.A. Griffith M. Hincke M. Characterization and inhibition of fibrin hydrogel-degrading enzymes during development of tissue engineering scaffolds. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1469. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jockenhoevel S. Zund G. Hoerstrup S.P. Chalabi K. Sachweh J.S. Demircan L., et al. Fibrin gel—advantages of a new scaffold in cardiovascular tissue engineering. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:424. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park K.H. Kim H. Moon S. Na K. Bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) loaded nanoparticles mixed with human mesenchymal stem cell in fibrin hydrogel for bone tissue engineering. J Biosci Bioeng. 2009;108:530. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee Y.B. Polio S. Lee W. Dai G. Menon L. Carroll R.S., et al. Bio-printing of collagen and VEGF-releasing fibrin gel scaffolds for neural stem cell culture. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:645. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moutos F.T. Guilak F. Functional properties of cell-seeded three-dimensionally woven poly(epsilon-caprolactone) scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1291. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed T.A. Dare E.V. Hincke M. Fibrin: a versatile scaffold for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:199. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linnes M.P. Ratner B.D. Giachelli C.M. A fibrinogen-based precision microporous scaffold for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5298. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinand C. Gupta R. Huang A.Y. Weinberg E. Madisch I. Qudsi R.A., et al. Comparison of hydrogels in the in vivo formation of tissue-engineered bone using mesenchymal stem cells and beta-tricalcium phosphate. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:757. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weinand C. Gupta R. Weinberg E. Madisch I. Jupiter J.B. Vacanti J.P. Human shaped thumb bone tissue engineered by hydrogel-beta-tricalciumphosphate/poly-epsilon-caprolactone scaffolds and magnetically sorted stem cells. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:46. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000264887.30392.72. discussion 52, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cen L. Liu W. Cui L. Zhang W. Cao Y. Collagen tissue engineering: development of novel biomaterials and applications. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:492. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31816c5bc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K.Y. Mooney D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem Rev. 2001;101:1869. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auger F.A. Rouabhia M. Goulet F. Berthod F. Moulin V. Germain L. Tissue-engineered human skin substitutes developed from collagen-populated hydrated gels: clinical and fundamental applications. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1998;36:801. doi: 10.1007/BF02518887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann P.M. Heimrath S. Kim B.S. Mooney D.J. Highly porous polymer matrices as a three-dimensional culture system for hepatocytes: initial results. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2032. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seliktar D. Black R.A. Vito R.P. Nerem R.M. Dynamic mechanical conditioning of collagen-gel blood vessel constructs induces remodeling in vitro. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28:351. doi: 10.1114/1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewus K.E. Nauman E.A. In vitro characterization of a bone marrow stem cell-seeded collagen gel composite for soft tissue grafts: effects of fiber number and serum concentration. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1015. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X. Black L. Santacana-Laffitte G. Patrick C.W., Jr Preparation and assessment of glutaraldehyde-crosslinked collagen-chitosan hydrogels for adipose tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:59. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinand C. Pomerantseva I. Neville C.M. Gupta R. Weinberg E. Madisch I., et al. Hydrogel-beta-TCP scaffolds and stem cells for tissue engineering bone. Bone. 2006;38:555. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahl D.A. Sachlos E. Liu C. Czernuszka J.T. Controlling the processing of collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:201. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0682-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delmage J.M. Powars D.R. Jaynes P.K. Allerton S.E. The selective suppression of immunogenicity by hyaluronic acid. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1986;16:303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richter A.W. Ryde E.M. Zetterstrom E.O. Non-immunogenicity of a purified sodium hyaluronate preparation in man. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1979;59:45. doi: 10.1159/000232238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim J. Kim I.S. Cho T.H. Lee K.B. Hwang S.J. Tae G., et al. Bone regeneration using hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel with bone morphogenic protein-2 and human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1830. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamane S. Iwasaki N. Majima T. Funakoshi T. Masuko T. Harada K., et al. Feasibility of chitosan-based hyaluronic acid hybrid biomaterial for a novel scaffold in cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:611. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jia X. Yeo Y. Clifton R.J. Jiao T. Kohane D.S. Kobler J.B., et al. Hyaluronic acid-based microgels and microgel networks for vocal fold regeneration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:3336. doi: 10.1021/bm0604956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui F.Z. Tian W.M. Hou S.P. Xu Q.Y. Lee I.S. Hyaluronic acid hydrogel immobilized with RGD peptides for brain tissue engineering. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:1393. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campoccia D. Doherty P. Radice M. Brun P. Abatangelo G. Williams D.F. Semisynthetic resorbable materials from hyaluronan esterification. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2101. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park Y.D. Tirelli N. Hubbell J.A. Photopolymerized hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels and interpenetrating networks. Biomaterials. 2003;24:893. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sannino A. Madaghiele M. Conversano F. Mele G. Maffezzoli A. Netti P.A., et al. Cellulose derivative-hyaluronic acid-based microporous hydrogels cross-linked through divinyl sulfone (DVS) to modulate equilibrium sorption capacity and network stability. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:92. doi: 10.1021/bm0341881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Segura T. Anderson B.C. Chung P.H. Webber R.E. Shull K.R. Shea L.D. Crosslinked hyaluronic acid hydrogels: a strategy to functionalize and pattern. Biomaterials. 2005;26:359. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo Y. Kirker K.R. Prestwich G.D. Cross-linked hyaluronic acid hydrogel films: new biomaterials for drug delivery. J Control Release. 2000;69:169. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vercruysse K.P. Marecak D.M. Marecek J.F. Prestwich G.D. Synthesis and in vitro degradation of new polyvalent hydrazide cross-linked hydrogels of hyaluronic acid. Bioconjug Chem. 1997;8:686. doi: 10.1021/bc9701095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shu X.Z. Liu Y. Luo Y. Roberts M.C. Prestwich G.D. Disulfide cross-linked hyaluronan hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:1304. doi: 10.1021/bm025603c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pouyani T. Prestwich G.D. Biotinylated hyaluronic acid: a new tool for probing hyaluronate-receptor interactions. Bioconjug Chem. 1994;5:370. doi: 10.1021/bc00028a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kongtawelert P. Ghosh P. A method for the quantitation of hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid) in biological fluids using a labeled avidin-biotin technique. Anal Biochem. 1990;185:313. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inuyama Y. Kitamura C. Nishihara T. Morotomi T. Nagayoshi M. Tabata Y., et al. Effects of hyaluronic acid sponge as a scaffold on odontoblastic cell line and amputated dental pulp. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;92:120. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peppas N.A. Keys K.B. Torres-Lugo M. Lowman A.M. Poly(ethylene glycol)-containing hydrogels in drug delivery. J Control Release. 1999;62:81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stosich M.S. Moioli E.K. Wu J.K. Lee C.H. Rohde C. Yoursef A.M., et al. Bioengineering strategies to generate vascularized soft tissue grafts with sustained shape. Methods. 2009;47:116. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papadopoulos A. Bichara D.A. Zhao X. Ibusuki S. Randolph M.A. Anseth K.S., et al. Injectable and photopolymerizable tissue-engineered auricular cartilage using PEGDM copolymer hydrogels. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:161. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu J. Bioactive modification of poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4639. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nguyen K.T. West J.L. Photopolymerizable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4307. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Al-Nasassrah M.A. Podczeck F. Newton J.M. The effect of an increase in chain length on the mechanical properties of polyethylene glycols. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1998;46:31. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(97)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gunn J.W. Turner S.D. Mann B.K. Adhesive and mechanical properties of hydrogels influence neurite extension. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;72:91. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nemir S. Hayenga H.N. West J.L. PEGDA hydrogels with patterned elasticity: novel tools for the study of cell response to substrate rigidity. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;105:636. doi: 10.1002/bit.22574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cruise G.M. Scharp D.S. Hubbell J.A. Characterization of permeability and network structure of interfacially photopolymerized poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1287. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stosich M.S. Bastian B. Marion N.W. Clark P.A. Reilly G. Mao J.J. Vascularized adipose tissue grafts from human mesenchymal stem cells with bioactive cues and microchannel conduits. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:2881. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lawson M.A. Barralet J.E. Wang L. Shelton R.M. Triffitt J.T. Adhesion and growth of bone marrow stromal cells on modified alginate hydrogels. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1480. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shoichet M.S. Li R.H. White M.L. Winn S.R. Stability of hydrogels used in cell encapsulation: An in vitro comparison of alginate and agarose. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;50:374. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960520)50:4<374::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuo C.K. Ma P.X. Ionically crosslinked alginate hydrogels as scaffolds for tissue engineering: part 1. Structure, gelation rate and mechanical properties. Biomaterials. 2001;22:511. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sakai S. Kawakami K. Synthesis and characterization of both ionically and enzymatically cross-linkable alginate. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:495. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eiselt P. Yeh J. Latvala R.K. Shea L.D. Mooney D.J. Porous carriers for biomedical applications based on alginate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1921. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alsberg E. Anderson K.W. Albeiruti A. Franceschi R.T. Mooney D.J. Cell-interactive alginate hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. J Dent Res. 2001;80:2025. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800111501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rowley J.A. Madlambayan G. Mooney D.J. Alginate hydrogels as synthetic extracellular matrix materials. Biomaterials. 1999;20:45. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dobie K. Smith G. Sloan A.J. Smith A.J. Effects of alginate hydrogels and TGF-beta 1 on human dental pulp repair in vitro. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:387. doi: 10.1080/03008200290000574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Awad H.A. Wickham M.Q. Leddy H.A. Gimble J.M. Guilak F. Chondrogenic differentiation of adipose-derived adult stem cells in agarose, alginate, and gelatin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3211. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lead J.R. Starchev K. Wilkinson K.J. Diffusion coefficients of humic substances in agarose gel and in water. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:482. doi: 10.1021/es025840n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sjoberg H. Persson S. Caram-Lelham N. How interactions between drugs and agarose-carrageenan hydrogels influence the simultaneous transport of drugs. J Control Release. 1999;59:391. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benya P.D. Shaffer J.D. Dedifferentiated chondrocytes reexpress the differentiated collagen phenotype when cultured in agarose gels. Cell. 1982;30:215. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Balgude A.P. Yu X. Szymanski A. Bellamkonda R.V. Agarose gel stiffness determines rate of DRG neurite extension in 3D cultures. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1077. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bellamkonda R. Ranieri J.P. Aebischer P. Laminin oligopeptide derivatized agarose gels allow three-dimensional neurite extension in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41:501. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jeong B. Bae Y.H. Kim S.W. Drug release from biodegradable injectable thermosensitive hydrogel of PEG-PLGA-PEG triblock copolymers. J Control Release. 2000;63:155. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torres-Lugo M. Peppas N.A. Transmucosal delivery systems for calcitonin: a review. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1191. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lin C.C. Metters A.T. Hydrogels in controlled release formulations: network design and mathematical modeling. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1379. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu L. Ding J. Injectable hydrogels as unique biomedical materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1473. doi: 10.1039/b713009k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yu L. Chang G.T. Zhang H. Ding J.D. Injectable block copolymer hydrogels for sustained release of a PEGylated drug. Int J Pharm. 2008;348:95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zentner G.M. Rathi R. Shih C. McRea J.C. Seo M.H. Oh H., et al. Biodegradable block copolymers for delivery of proteins and water-insoluble drugs. J Control Release. 2001;72:203. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jeong J.H. Kim S.W. Park T.G. Biodegradable triblock copolymer of PLGA-PEG-PLGA enhances gene transfection efficiency. Pharm Res. 2004;21:50. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000012151.05441.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee P.Y. Li Z. Huang L. Thermosensitive hydrogel as a Tgf-beta1 gene delivery vehicle enhances diabetic wound healing. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1995. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000008048.58777.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Herberg S. Siedler M. Pippig S. Schuetz A. Dony C. Kim C.K., et al. Development of an injectable composite as a carrier for growth factor-enhanced periodontal regeneration. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:976. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kwon D.H. Bennett W. Herberg S. Bastone P. Pippig S. Rodriguez N.A., et al. Evaluation of an injectable rhGDF-5/PLGA construct for minimally invasive periodontal regenerative procedures: a histological study in the dog. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:390. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tan K.H. Chua C.K. Leong K.F. Cheah C.M. Gui W.S. Tan W.S., et al. Selective laser sintering of biocompatible polymers for applications in tissue engineering. Biomed Mater Eng. 2005;15:113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wiria F.E. Leong K.F. Chua C.K. Liu Y. Poly-epsilon-caprolactone/hydroxyapatite for tissue engineering scaffold fabrication via selective laser sintering. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:1. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sarasam A. Madihally S.V. Characterization of chitosan-polycaprolactone blends for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5500. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Choong C.S. Hutmacher D.W. Triffitt J.T. Co-culture of bone marrow fibroblasts and endothelial cells on modified polycaprolactone substrates for enhanced potentials in bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2521. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li X. Xie J. Yuan X. Xia Y. Coating electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) fibers with gelatin and calcium phosphate and their use as biomimetic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Langmuir. 2008;24:14145. doi: 10.1021/la802984a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Erisken C. Kalyon D.M. Wang H. Functionally graded electrospun polycaprolactone and beta-tricalcium phosphate nanocomposites for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4065. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Venugopal J. Zhang Y.Z. Ramakrishna S. Fabrication of modified and functionalized polycaprolactone nanofibre scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:2138. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kim H.W. Knowles J.C. Kim H.E. Development of hydroxyapatite bone scaffold for controlled drug release via poly(epsilon-caprolactone) and hydroxyapatite hybrid coatings. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;70:240. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang H.G. Zhu Q. Preparation of porous hydroxyapatite with interconnected pore architecture. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:1825. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fu Q. Rahaman M.N. Dogan F. Bal B.S. Freeze casting of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds. I. Processing and general microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;86:125. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sepulveda P. Binner J.G. Rogero S.O. Higa O.Z. Bressiani J.C. Production of porous hydroxyapatite by the gel-casting of foams and cytotoxic evaluation. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200004)50:1<27::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhang Y. Zhang M. Three-dimensional macroporous calcium phosphate bioceramics with nested chitosan sponges for load-bearing bone implants. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61:1. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Li S.H. De Wijn J.R. Layrolle P. de Groot K. Synthesis of macroporous hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;61:109. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Montjovent M.O. Mathieu L. Hinz B. Applegate L.L. Bourban P.E. Zambelli P.Y., et al. Biocompatibility of bioresorbable poly(L-lactic acid) composite scaffolds obtained by supercritical gas foaming with human fetal bone cells. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1640. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bouler J.M. Trecant M. Delecrin J. Royer J. Passuti N. Daculsi G. Macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics: influence of five synthesis parameters on compressive strength. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;32:603. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199612)32:4<603::AID-JBM13>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu D.M. Fabrication of hydroxyapatite ceramic with controlled porosity. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1997;8:227. doi: 10.1023/a:1018591724140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu Y. Kim J.H. Young D. Kim S. Nishimoto S.K. Yang Y. Novel template-casting technique for fabricating beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds with high interconnectivity and mechanical strength and in vitro cell responses. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92:997. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mondrinos M.J. Dembzynski R. Lu L. Byrapogu V.K. Wootton D.M. Lelkes P.I., et al. Porogen-based solid freeform fabrication of polycaprolactone-calcium phosphate scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4399. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Friedman C.D. Costantino P.D. Takagi S. Chow L.C. BoneSource hydroxyapatite cement: a novel biomaterial for craniofacial skeletal tissue engineering and reconstruction. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;43:428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199824)43:4<428::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tancred D.C. McCormack B.A. Carr A.J. A synthetic bone implant macroscopically identical to cancellous bone. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2303. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang F. Chang J. Lu J. Lin K. Ning C. Bioinspired structure of bioceramics for bone regeneration in load-bearing sites. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:896. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Linde A. Hedner E. Recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 enhances bone healing, guided by osteopromotive e-PTFE membranes: an experimental study in rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;56:549. doi: 10.1007/BF00298588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bow J.S. Liou S.C. Chen S.Y. Structural characterization of room-temperature synthesized nano-sized beta-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 2004;25:3155. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hsu Y.H. Turner I.G. Miles A.W. Mechanical characterization of dense calcium phosphate bioceramics with interconnected porosity. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:2319. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kumta P.N. Sfeir C. Lee D.H. Olton D. Choi D. Nanostructured calcium phosphates for biomedical applications: novel synthesis and characterization. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:65. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ramay H.R. Zhang M. Biphasic calcium phosphate nanocomposite porous scaffolds for load-bearing bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5171. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Santos F.A. Pochapski M.T. Martins M.C. Zenobio E.G. Spolidoro L.C. Marcantonio E., Jr Comparison of biomaterial implants in the dental socket: histological analysis in dogs. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2010;12:18. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2008.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Duailibi M.T. Duailibi S.E. Young C.S. Bartlett J.D. Vacanti J.P. Yelick P.C. Bioengineered teeth from cultured rat tooth bud cells. J Dent Res. 2004;83:523. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Young C.S. Terada S. Vacanti J.P. Honda M. Bartlett J.D. Yelick P.C. Tissue engineering of complex tooth structures on biodegradable polymer scaffolds. J Dent Res. 2002;81:695. doi: 10.1177/154405910208101008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Duailibi S.E. Duailibi M.T. Zhang W. Asrican R. Vacanti J.P. Yelick P.C. Bioengineered dental tissues grown in the rat jaw. J Dent Res. 2008;87:745. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kuo T.F. Huang A.T. Chang H.H. Lin F.H. Chen S.T. Chen R.S., et al. Regeneration of dentin-pulp complex with cementum and periodontal ligament formation using dental bud cells in gelatin-chondroitin-hyaluronan tri-copolymer scaffold in swine. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:1062. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Young C.S. Abukawa H. Asrican R. Ravens M. Troulis M.J. Kaban L.B., et al. Tissue-engineered hybrid tooth and bone. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1599. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ohazama A. Modino S.A. Miletich I. Sharpe P.T. Stem-cell-based tissue engineering of murine teeth. J Dent Res. 2004;83:518. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mantesso A. Sharpe P. Dental stem cells for tooth regeneration and repair. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:1143. doi: 10.1517/14712590903103795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Modino S.A. Sharpe P.T. Tissue engineering of teeth using adult stem cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:255. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sonoyama W. Liu Y. Fang D. Yamaza T. Seo B.M. Zhang C., et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nakao K. Morita R. Saji Y. Ishida K. Tomita Y. Ogawa M., et al. The development of a bioengineered organ germ method. Nat Methods. 2007;4:227. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ikeda E. Morita R. Nakao K. Ishida K. Nakamura T. Takano-Yamamoto T., et al. Fully functional bioengineered tooth replacement as an organ replacement therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Abukawa H. Zhang W. Young C.S. Asrican R. Vacanti J.P. Kaban L.B., et al. Reconstructing mandibular defects using autologous tissue-engineered tooth and bone constructs. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:335. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Xu W.P. Zhang W. Asrican R. Kim H.J. Kaplan D.L. Yelick P.C. Accurately shaped tooth bud cell-derived mineralized tissue formation on silk scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:549. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Richter W. Mesenchymal stem cells and cartilage in situ regeneration. J Intern Med. 2009;266:390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lee C.H. Marion N.W. Hollister S. Mao J.J. Tissue formation and vascularization of anatomically shaped human joint condyle ectopically in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3923. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yelick P.C. Vacanti J.P. Bioengineered teeth from tooth bud cells. Dent Clin North Am. 2006;50:191. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2005.11.005. viii, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Belema-Bedada F. Uchida S. Martire A. Kostin S. Braun T. Efficient homing of multipotent adult mesenchymal stem cells depends on FROUNT-mediated clustering of CCR2. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:566. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Nait Lechguer A. Kuchler-Bopp S. Hu B. Haikel Y. Lesot H. Vascularization of engineered teeth. J Dent Res. 2008;87:1138. doi: 10.1177/154405910808701216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Herodin F. Bourin P. Mayol J.F. Lataillade J.J. Drouet M. Short-term injection of antiapoptotic cytokine combinations soon after lethal gamma -irradiation promotes survival. Blood. 2003;101:2609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kitaori T. Ito H. Schwarz E.M. Tsutsumi R. Yoshitomi H. Oishi S., et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for the recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the fracture site during skeletal repair in a mouse model. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:813. doi: 10.1002/art.24330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Alhadlaq A. Mao J.J. Mesenchymal stem cells: isolation and therapeutics. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:436. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Crisan M. Chen C.W. Corselli M. Andriolo G. Lazzari L. Peault B. Perivascular multipotent progenitor cells in human organs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1176:118. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Steinhardt Y. Aslan H. Regev E. Zilberman Y. Kallai I. Gazit D., et al. Maxillofacial-derived stem cells regenerate critical mandibular bone defect. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1763. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Itoh F. Asao H. Sugamura K. Heldin C.H. ten Dijke P. Itoh S. Promoting bone morphogenetic protein signaling through negative regulation of inhibitory Smads. EMBO J. 2001;20:4132. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hahn G.V. Cohen R.B. Wozney J.M. Levitz C.L. Shore E.M. Zasloff M.A., et al. A bone morphogenetic protein subfamily: chromosomal localization of human genes for BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. Genomics. 1992;14:759. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Mao J.J. Stosich M.S. Moioli E.K. Lee C.H. Fu S.Y. Bastian B., et al. Facial reconstruction by biosurgery: cell transplantation versus cell homing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:257. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lee C.H. Marion N.W. Hollister S. Mao J.J. Tissue formation and vascularization in anatomically shaped human joint condyle ectopically in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3923. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Yang R. Chen M. Lee C.H. Yoon R. Lal S. Mao J.J. Clones of ectopic stem cells in the regeneration of muscle defects in vivo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ohara T. Itaya T. Usami K. Ando Y. Sakurai H. Honda M.J., et al. Evaluation of scaffold materials for tooth tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:800. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Reddi A.H. Role of morphogenetic proteins in skeletal tissue engineering and regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:247. doi: 10.1038/nbt0398-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Nakashima M. Reddi A.H. The application of bone morphogenetic proteins to dental tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1025. doi: 10.1038/nbt864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Langer R. Vacanti J.P. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]