Abstract

We present results from the OP3 campaign in Sabah during 2008 that allow us to study the impact of local emission changes over Borneo on atmospheric composition at the regional and wider scale. OP3 constituent data provide an important constraint on model performance. Treatment of boundary layer processes is highlighted as an important area of model uncertainty. Model studies of land-use change confirm earlier work, indicating that further changes to intensive oil palm agriculture in South East Asia, and the tropics in general, could have important impacts on air quality, with the biggest factor being the concomitant changes in NOx emissions. With the model scenarios used here, local increases in ozone of around 50 per cent could occur. We also report measurements of short-lived brominated compounds around Sabah suggesting that oceanic (and, especially, coastal) emission sources dominate locally. The concentration of bromine in short-lived halocarbons measured at the surface during OP3 amounted to about 7 ppt, setting an upper limit on the amount of these species that can reach the lower stratosphere.

Keywords: tropospheric ozone, biogenic organic compounds, rainforest, isoprene, atmospheric modelling

1. Introduction

The geography of South East Asia makes it a particularly interesting and important region for atmospheric science. It is an area of tropical rainforests, whose many roles in climate and weather are well documented. The forests are crucially important for the energy balance of the atmosphere and for hydrological processes; they are a major carbon store; they provide surface emission and deposition routes for the exchange of chemically active gases; and convection over the forests can lift chemically active material into the free troposphere. The South East Asian rainforests differ from those in South America and Africa by being located in a region which is also massively influenced by ocean processes. The Maritime Continent of South East Asia is a mosaic of islands surrounded by a very warm ocean and so is the region of strongest, deepest convective activity worldwide. Surface chemical processes here are therefore most likely to have wider geographical impacts. Concern about rainforests is, of course, heightened by the speed at which they are changing. As in other regions, this is also true in South East Asia where logging and the development of industries based on oil palm are major factors. In addition, the warm waters of the Maritime Continent are increasingly being exploited so that changing aquaculture [1] might also have an atmospheric impact.

The OP3 campaign, based in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, provided an opportunity to study a number of the tropical processes related to atmospheric chemistry and aerosols. Hewitt et al. [2,3] provide a detailed description of the campaign objectives and various approaches and techniques adopted. Ground-based measurements at the Bukit Atur Global Atmosphere Watch station in the Danum Valley forest conservation area in Sabah, Malaysia (4°58′ N, 117°50′ E, 426 m above mean sea level) and at the Sabahmas oil palm plantation, also in Sabah (5°4′ N, 118°27′ E), owned by Wilmar International Ltd., were complemented by airborne measurements made using the FAAM BAe146 research aircraft. Intensive measurements of surface–atmosphere exchange (reviewed by Fowler et al. [4]) and of atmospheric composition and aerosols (reviewed by MacKenzie et al. [5]) have allowed new information to be obtained about important atmospheric processes. These have been complemented by numerical modelling studies where the new information on processes is integrated in an attempt to synthesize understanding. These models can then provide a powerful diagnostic and prognostic framework for further investigation.

In this paper, we will focus on those aspects of the OP3 study which considered how local processes in South East Asia can impact the regional and wider scales. In particular, here we consider two specific problems. The first is how large-scale changes in land use could impact local air quality and atmospheric composition generally on regional scales (§§2–4). Secondly, in §§5 and 6, we explore some uncertainties related to the role that halogen species, emitted in South East Asia, play in regional and global atmospheric chemistry. In the following sections, we consider these two problems in more detail.

2. Tropospheric ozone and land-use change

Ozone in the troposphere plays many roles. It is a crucial factor influencing climate, and climate change; it is central in the control of the oxidizing capacity of the atmosphere, and in air quality. The distribution of ozone in the troposphere depends on transport downwards from the stratosphere and within the troposphere, on in situ photochemical production and destruction, and on deposition at the surface. The chemical processes controlling tropospheric ozone are complex; both net ozone production and ozone destruction regimes exist, which depend in a nonlinear fashion on the local abundance of the oxides of nitrogen (NO + NO2 = NOx) and of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). How local ozone responds to changes in NOx or VOC concentrations depends on the regime. In NOx-rich environments, like the industrialized Northern Hemisphere, a decrease in NOx (or an increase in VOC) might be expected to lead to an increase in ozone. In many regions of the tropics, which are relatively NOx-poor, a decrease in NOx (or increase in VOC) might, in contrast, be expected to lead to a decrease in ozone (for more discussion on the dependence of ozone production on the chemical regime, see [6,7]).

Because of its many significant roles in the environment, ozone has been an important focus of global change studies. Prather et al. [8] projected extremely large surface ozone changes later this century using a range of atmospheric chemistry models under the, perhaps extreme, Special Report on Emission Scenarios (SRES) A2 scenario. Stevenson et al. [9] revisited these calculations with new scenarios out to 2030 using a number of chemistry–climate models. More recently, a report by the Royal Society [10] has also highlighted possible ozone change later this century. A key finding from all these studies is that the size of the ozone change depends crucially on the details of the combined changes in VOCs and NOx.

All these studies were based on projections of changes in the anthropogenic emissions of NOx and VOCs. However, it is clear that biogenic (and climate-sensitive) processes also play a key role in controlling ozone concentrations. The tropical biosphere is particularly important for the chemistry and deposition processes involved in the budget of tropospheric ozone. For example, the biogenic emissions of VOCs far outweigh anthropogenic emissions into the atmosphere, currently by about a factor of 10 (e.g. [11]). Furthermore, forests are the major emitters of a range of biogenic VOCs (BVOCs), with tropical emissions accounting for about half the total [12,13]. Isoprene is perhaps the most important biogenic emission for local atmospheric chemistry. A number of the terpenes, emitted as BVOCs, are also involved in the generation of secondary organic aerosol and are important in radiative transfer processes. Isoprene has an emission strength similar to that of methane (approx. 500 T gC yr–1) but, unlike methane, it has a short lifetime in the atmosphere, of the order of hours, and has an active, local atmospheric chemistry. The emissions come from a wide range of vegetation types and are strongly temperature-dependent, and also depend on incoming solar radiation, on soil moisture and on ambient CO2 levels [12,14,15]. Significant changes in isoprene emissions are thus expected as climate changes. As most of the emissions occur from tropical forests, land-use change could also have a large impact on total emissions and hence on air quality. Therefore, changes in the tropical biosphere, and particularly the forests, could have an important impact on ozone and climate, with important feedbacks possible.

Tropical forests account for more than half the world's forest and they are changing at a rapid rate, through logging and the change of use to agriculture or different tree crops (often monocultures). In Malaysia, 13 per cent of land is now covered by oil palm plantations, compared with 1 per cent less than 40 years ago [3]. Production for the global food industry has been one of the major drivers. Biofuels have been seen as environmentally friendly alternatives to fossil fuels but in recent years various questions have been raised about some potential negative impacts on greenhouse gas concentrations [16] and on air quality [2]. Analysis of all the stages relevant to these technologies are necessary and OP3 has provided some important new information on emissions and atmospheric chemistry. Flux measurements of isoprene, over both rainforest and oil palm plantations, and of NOx, have been made [4,17,18]. In addition, a range of in situ chemistry measurements has allowed the local chemical processes to be explored [5]. For example, OP3 measurements find higher OH concentrations than predicted with conventional chemical schemes, consistent with earlier tropical observations in low NOx environments [19]. One possibility is that OH is recycled during isoprene oxidation, but other ideas have also been put forward to explain the OH observations (e.g. [20]). The precise reasons for the higher than expected OH are still to be resolved; most global models do not yet include the relevant processes but some initial calculations have been performed, as mentioned in §3.

In §4, we present calculations with a box model and with a global chemistry–climate model, which explore possible future local and regional changes in ozone in response to changes in emissions over South East Asia, based on our OP3 results. First, §3 looks at some background OP3 studies which have placed local tropical measurements in a regional context and which have explored the validation of global models using local, tropical measurements.

3. Local–regional–global modelling

(a). Regional impact in the context of satellite data

Satellite observations of trace gases allow us to put the surface and aircraft data collected during OP3 into a wider spatial context, relative to Borneo and the larger South East Asian region, and into a longer temporal context.

Here, we focus on formaldehyde (HCHO), which is a good indicator of biogenic emissions, biomass burning and photochemical activity, to examine the atmospheric chemistry over Borneo during the OP3 campaigns in 2008. Global background concentrations of HCHO are determined by the balance between the source (from the oxidation of methane) and the OH and photolysis sinks. Concentrations are typically much larger over continents owing to additional sources from the oxidation of biogenic and anthropogenic VOCs, and from biomass burning (either directly released or from the oxidation of co-emitted VOCs) [21,22].

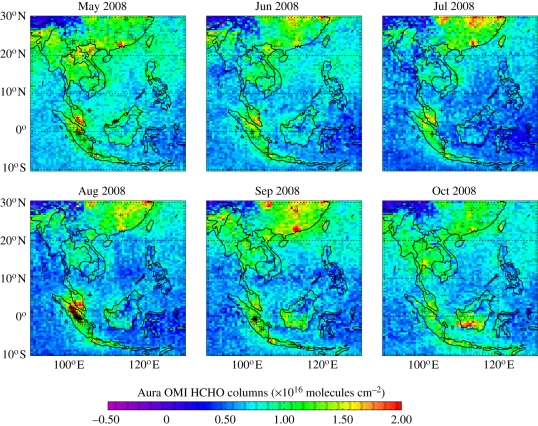

Figure 1 shows HCHO column distributions over Borneo during May–October 2008, quantified using UV spectroscopic measurements (327.5–356.5 nm) from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) [23]. OMI is an instrument aboard the NASA EOS-Aura spacecraft (http://aura.gsfc.nasa.gov/), launched in July 2004 in a near-polar sun-synchronous orbit, with an equatorial local overpass time of 13.45. It scans the atmosphere in the nadir direction with 60 across-track pixels along a swath of 2600 km that permits near-global coverage in 1 day. The finest spatial resolution is 13 × 24 km2 at nadir, degrading towards swath edges; data are averaged on a 0.5° × 0.67° grid. Scenes with cloud fraction greater than 40 per cent using OMI cloud products are discarded, as well as data that do not satisfy fit convergence and statistical outliers. OMI has a limit of detection for HCHO of about 8 × 1015 molecules cm−2.

Figure 1.

Monthly mean HCHO columns (1016 molecules per square centimetre) from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) over South East Asia for May–October, 2008, averaged on a 0.5° × 0.67° grid. The OMI data are for local equatorial overpass time of 13.45 and correspond to observations with cloud cover less than 40%. The superimposed black crosses denote fire-count measurements from the Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer (AATSR) that provide a qualitative measure of fire activity.

The largest observed HCHO columns over South East Asia are loosely correlated with Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer (AATSR) fire-counts (denoted by black crosses) [24] and hence are probably due to fire emissions [22]. During May, enhanced HCHO columns over the Gulf of Thailand may reflect outflow from fires occurring in Sumatra and from the Sibu area of eastern Borneo. However, during the OP3 campaigns, fire activity over Malaysian Borneo was minimal and the levels of HCHO were generally low, with their column amounts typically approaching their background values of 4 × 1015 molecules cm−2. These low values also suggest that during the OP3 measurement period, the HCHO source from BVOC oxidation was weak resulting in a diffuse observed signal. We observe a slight HCHO enhancement during April over Danum Valley (not shown) but it is difficult to make a source attribution. Interpretation of the trace gas and land surface satellite data suggests that oxidant chemistry over the broader South East Asia region is determined largely by widespread biomass burning. Preliminary model calculations show that the free troposphere over Danum Valley experiences long-range transport of biomass burning pollutants from other parts of Borneo and from other upwind countries.

Analysis of a 12 year time series of monthly mean HCHO columns retrieved from the GOME and SCIAMACHY satellite instruments [25,26] and ATSR/AATSR fire-counts [24,27] confirm that biomass burning over Borneo drives observed variability of HCHO [3]. Anomalously high HCHO columns over this period were owing to intense burning periods associated with strong El Niño conditions, as expected. Recent work showed that spatial correlations between the 12 year record of HCHO columns and the associated assimilated meteorological data, vegetation activity and fire-counts were strongest in southernmost Borneo and not over the Bukit Atur (Danum Valley) region [28].

We conclude that the low trace gas columns observed over this region during 2008 are consistent with our understanding of past variability, suggesting that conclusions reached from the interpretation of the OP3 data can be applied to similar months from other years.

(b). Model comparison with measurements

During OP3, a range of atmospheric composition measurements was made in the Danum Valley and from the FAAM BAe146 research aircraft, which made a series of survey flights of Sabah, including low-level flights over Danum [3,5]. These measurements allow local chemical and physical processes to be investigated and their treatments in atmospheric models to be evaluated. Large-scale models are frequently used to assess global scale problems. Evaluating these models against local measurements is necessary but not without difficulty, particularly near the surface where a range of processes are important in determining composition. The chemical process assessment using chemical box models must also be performed with the global models. Several aspects of the evaluation process can be identified. First, how representative are the measurements? The large-scale study reported in §3a suggests that the OP3 measurements in 2008 are not anomalous. Second, are the chemical mechanisms appropriate? Third, does the treatment of physical processes affect the comparison? Fourth, how important is the model spatial resolution? These aspects were considered in the evaluation of the OP3 data and are discussed below.

MacKenzie et al. [5] describe the use of box models to explore a number of aspects of tropospheric oxidation chemistry. For example, there is currently great interest in the details of isoprene oxidation in clean tropical environments. Measurements above a South American rainforest in Suriname [19] showed much higher concentrations of OH and HO2 (i.e. HOx) than expected with current theories, prompting the idea that HOx is somehow ‘recycled’ during isoprene oxidation. OP3 measurements have allowed these ideas to be explored over a different environment, the South East Asian rainforest. Thus (see [5] for more details), it was found using the CiTTyCAT box model of atmospheric chemistry [29,30] that while NOx and O3 chemistry could be represented well during the daytime, the default model compared poorly with the daytime observations of VOC and OH-mixing ratios. In particular, the concentration of OH during the day was substantially underestimated, and some VOC oxidation products were substantially overestimated. Pugh et al. [20] and Stone et al. [30] conducted a series of sensitivity studies with modifications to the chemical scheme, in order to investigate revisions to the isoprene-OH chemistry proposed by recent studies [19,31]. Their results suggested that, for this rainforest location, these modifications were not able to improve the overall model fit to the measurements.

Comparison of the box model with night-time observations suggests that accurate representation of physical processes is key to reproducing observed behaviour in this particular campaign (a point discussed in more detail below). Weak night-time mixing above the rainforest site makes an unmodified box modelling approach unsuitable for simulation of measurements made at night [32], although it did prove possible to provide a parametrized nocturnal deposition velocity for O3 that improved the comparison of measured and box-modelled concentrations at day-break and through the subsequent day. Furthermore, Pugh et al. [20] found that daytime overestimation of VOC oxidation products could be largely corrected by implementing wet deposition in the model, and also including a substantial dry deposition velocity (approx. 1.5 cm s−1) for the compounds methacrolein (MACR) and methylvinyl ketone (MVK). This dry deposition velocity agrees well with eddy-covariance flux measurements of MACR and MVK made over the oil palm plantation during OP3 [33,34] and is consistent with recent measurements of oxidized VOC deposition to vegetation made by Karl et al. [35]. Thus, as in the Pike et al. [36] study discussed below, the role of physical processes in the boundary layer is important for chemical composition near the surface.

Complementing the box model study of Pugh et al. [20], Archibald et al. [37] have used a global chemistry–climate model, UKCA, to assess the impact of uncertainty in the oxidation of isoprene. A parametrized version of Peeters and co-workers [31,38] HOx regenerating/recycling mechanism was implemented based on the reactions outlined by Archibald et al. [39]. Essentially, the regeneration of HOx comes about through very fast unimolecular decomposition and subsequent oxidation of specific conformers of the isoprene hydroxy-peroxy radical pool. The UKCA model was run at quite a coarse spatial resolution and thus suffers from some of the issues associated with representing dynamics of the rainforest environment as highlighted in box model studies (see [5], and below). However, Archibald et al. [37] provide convincing support for Peeters' mechanism based on comparing the present-day results with and without their updated isoprene scheme to some of the ground-based measurements made during OP3 (see fig. 1 of Archibald [37]). One of the main conclusions of the work of Pugh et al. [20] and Archibald et al. [37] is that although novel chemical mechanisms can help to reconcile models with measurements of OH, this is usually to the detriment of other chemical species. For example, Archibald et al. [37] show that although comparison with OH is improved, HO2 and the organic peroxy radical (RO2) concentrations tend to increase to levels beyond the stated uncertainty of the measurements. This observation could provide some support for the argument of Hofzumahaus et al. [40] and Whalley et al. [41] of species able to act like NO and convert HO2 to OH. However, to date no species have been identified as being able to propagate this chemistry at the rate required to reconcile measurements and modelling of HOx in these pristine environments.

It is worth mentioning that although resolution of the OH recycling story is clearly important if the aim is to reproduce observed surface oxidant concentrations, perturbation experiments, which assess the change in oxidants under different climate or emission scenarios, are less sensitive to this aspect of the model chemical mechanism. This is true both for the preindustrial and future experiments reported by Archibald et al. [37] and for the land-use change experiments reported in §4b.

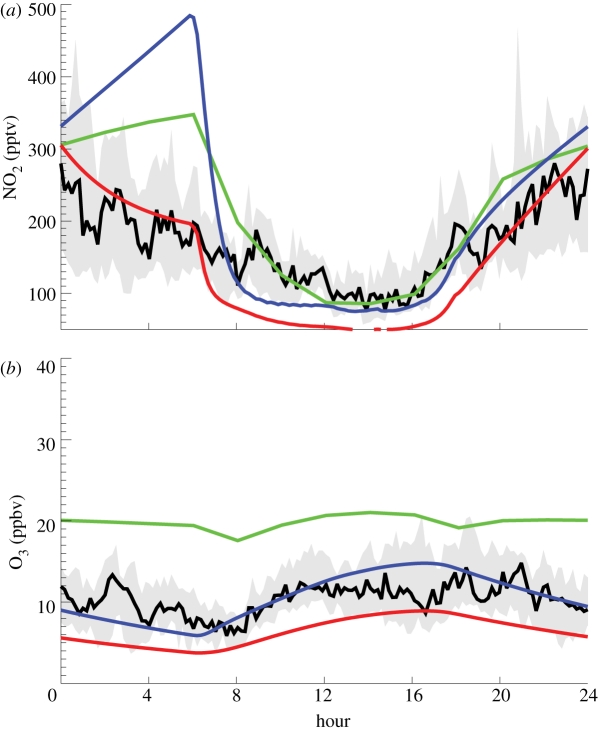

OP3 scientists have also looked at the role of physical processes in controlling atmospheric composition, especially in the boundary layer, and the importance of emissions at the small spatial scale. The boundary layer is an important region that connects the surface, where emissions and deposition occur, with the free troposphere. There is little diurnal variation of the boundary layer over the ocean but much more over land, with a greater boundary layer height during the daytime. In areas of complex topography, like the Danum Valley, modelling the behaviour of the boundary layer can be particularly difficult. Pike et al. [36] could not model the observed diurnal variation of ozone and NOx at the Danum Valley without introducing an idealized treatment of the boundary layer. Figure 2 summarizes the main findings of that study which compared local observations with model calculations employing both a box model and a three-dimensional global chemical transport model. Ozone from the Cambridge global model p-TOMCAT [42,43] considerably overestimates observations, as discussed further below. The diurnal behaviour of NO2 in p-TOMCAT is broadly consistent with the data, but the model completely fails to capture the observed behaviour between midnight and dawn; observed NO2 drops but it increases in the model. The modelled behaviour of NO2 is initially even worse in the box model, which shows a very strong night-time increase. In contrast, ozone is modelled well in the box model. Meteorological observations during OP3 show strong static stability above the Bukit Atur site at night (see [3], figure 2); the hilltops, such as Bukit Atur, are also decoupled from the valleys, in which fog forms [44]. Eddy-covariance heat and momentum fluxes indicate that sensible and latent heat fluxes follow total solar radiation flux closely, while non-zero momentum fluxes continue into the night, consistent with the development of convection through the day slowly dissipating into the night [4]. Pike et al. [36] argue that the night-time boundary layer often collapsed after midnight, so hilltop measurements in the hours after midnight were more representative of the free troposphere. The OP3 aircraft measurements show little vertical variation for ozone between boundary layer and free troposphere (ozone concentrations increase slightly with altitude). In contrast, NO2 concentrations fall significantly with altitude. To represent the collapse of the boundary layer, Pike et al. [36] introduced a model ‘dilution’, with modelled concentrations in the boundary layer box being mixed with very clean (very low NOx) air from above between midnight to dawn. The box model was then able to reproduce the measured diurnal variation of NO2 extremely well, although ozone was then actually underestimated. But given the small variation of ozone with height, it is clear that mixing of boundary layer and free troposphere air should not reduce the ozone concentration at the surface: a better representation for ozone is the model without dilution (see [36] for further details) or simple chemistry in a one-dimensional model that can capture the strong nocturnal static stability [32].

Figure 2.

Modelled diurnal variation of NO2 and ozone at Danum Valley in April, compared with observations (black line, data) made in April 2008 during OP3. Red lines, box with dilution; blue lines, box with no dilution; green lines, HighRes p-TOMCAT.

These box model studies illustrate the importance of representing physical processes in the boundary layer in models to study surface composition and the difficulty of comparing average model behaviour with observations made under particular conditions. They also emphasize the impact of topography in determining small-scale flow, which can significantly influence the observed concentrations.

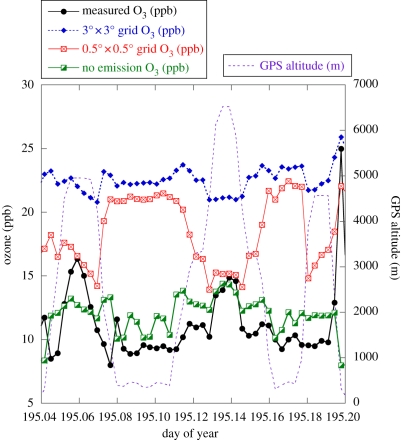

Global models usually have grid boxes with horizontal dimensions of at least tens of kilometres so that important processes are averaged out. See MacKenzie et al. [5] for a discussion of the ‘segregation’ concept: that the inability to model accurately both OH and isoprene simultaneously could be owing to the failure to represent a sub-grid segregation of air into separate parcels with high OH and high isoprene, respectively. Other aspects of model resolution have been explored using the global model, p-TOMCAT. For example, in the study of Hewitt et al. [3], results of global simulations were presented at two horizontal resolutions. The first resolution, approximately 3° × 3°, is typical of atmospheric chemistry integrations for the globe on multi-decadal timescales while the second, approximately 0.5° × 0.5°, is more typical of higher resolution process investigation studies. At the lower resolution Borneo is barely resolved, being only four grid cells wide, and the model significantly overestimated ozone over Borneo. Little spatial structure in the surface ozone field over Borneo was captured and detailed comparisons between p-TOMCAT results and observations from aircraft flights failed to show the observed structure. In contrast, at a resolution of 0.5°, the model captured better the differences in ozone concentrations between land and ocean, and ozone concentrations over land were somewhat lower, improving agreement with observations. A major reason for the improvement at the higher resolution was that the contrast between surface deposition of ozone, an important part of the ozone budget, to the land (high deposition) and to the ocean (low deposition) was captured much better than at the low resolution.

Some of the impacts of resolution can be seen in figure 3, which compares a number of different global model calculations with aircraft data collected on 3 July (day 195). Note that the flight altitude is plotted as the dotted blue line. Much of the flight is at low altitudes but there are two excursions into the free troposphere. Ozone calculated in the low-resolution model (shown in blue) is very much higher than observed (black). In contrast, the model run at a resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° calculates somewhat lower ozone and starts to capture some observed structure (see also [45]). In particular, ozone in the free troposphere is reproduced well at high horizontal resolution (the vertical resolution is unaltered) although the modelled boundary layer ozone is still generally a lot higher than observed. The difficulty of reproducing boundary layer ozone in this region is evident again. Inadequate modelling of convection or vertical mixing processes may be the reason, but it is likely that the parametrization of surface deposition in the model could also be responsible for the difference. Another possibility is unrealistic representation of emissions at the grid scale. A further run was carried out in which the emission of NOx was set to zero several days before the comparison (the green line). Now the observed and modelled boundary layer ozone agree better, both in magnitude and also to some extent in spatial structure. It is clear that detailed understanding of emissions is required. Use of low-resolution emission fields is inappropriate when studying high spatial resolution data; small (sub-grid) spatial variations in NOx emissions could have important consequences at the local scale.

Figure 3.

Comparison of ozone measured on the BAe146 on 3 July 2008 (black line) with various model calculations using the p-TOMCAT model at two different horizontal resolutions (red, approx. 0.5° × 0.5°; blue, approx. 3.0° × 3.0°), where the model fields are sampled at the flight positions. Results from a run at 0.5° × 0.5° resolution with NOx emission set to zero at the end of June is shown in green. Aircraft altitude is plotted as the blue dotted line.

4. Ozone changes—the response to changes in local emissions

(a). Box model studies

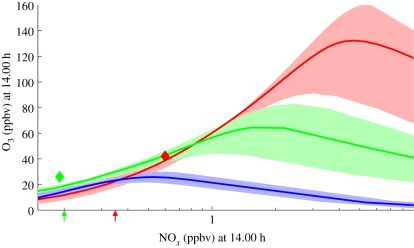

Oil palm is one of the world's most rapidly expanding equatorial crops, with Indonesia and Malaysia being the two largest producing countries. In order to test the vulnerability of local ozone concentrations to a change of land use away from natural rainforest, three different land-use scenarios were tested using the CiTTyCAT box model: (i) natural rainforest, (ii) oil palm plantations, and (iii) no BVOC emission (e.g. soya/sugar cane plantations). VOC emissions used for each of these scenarios are given in table 1. Each scenario was repeated several times while varying the NOx emissions from 0 to 0.8 mg N m−2 h−1, and also by varying the VOC by ±50 per cent to provide the shaded areas of model response shown in figure 4. The box model was run over the OP3 Bukit Atur measurement site (117.83° E, 5.0° N). Runs were carried out for eight days to achieve a reproducible diurnal cycle, with comparisons being made using output from the last day. The model and set-up used here is described in detail by Pugh et al. [20]. Wet and dry deposition was enabled for all runs.

Table 1.

VOC emissions fed to the CiTTyCAT model for each scenario shown in figure 4. Emissions of isoprene and monoterpenes were output using the MEGAN PCEEA algorithm [13] using measured values of light and temperature at the OP3 rainforest and plantation measurement sites. These modelled emissions were then scaled to match the average integrated emission flux over a day measured by eddy-covariance at the two sites. Anthropogenic emissions where taken from the inventory of Ohara et al. [46] and no diurnal cycle was applied.

| scenario | emissions used in model run (mg C m−2 h−1; 24 h average) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| isoprene | monoterpenes | total anthropogenic VOCs | |

| Borneo rainforest | 0.48a | 0.12a | 0.04b |

| oil palm plantation | 2.35a | 0.03a | 0.04b |

| no BVOC (e.g. soya/sugar canec) | 0 | 0 | 0.04b |

Figure 4.

Ozone response of different VOC emission scenarios, driven by possible land-use change, to a change in NOx, as computed by the CiTTyCAT box model (lines) and the p-TOMCAT model (diamonds, for FOREST and OILPALM2 scenarios, see §4b). Results are plotted at a local time of 14.00 from each model (with the CiTTyCAT model run to a steady diurnal cycle). Typical contemporary forest and oil palm landscape NOx mixing ratios are indicated by the coloured arrows on the x-axis. Green line, rainforest landscape; red line, oil palm landscape; blue line, no BVOC landscape; shading shows effect of ±50% VOC flux on predicted ozone.

Figure 4 shows how ozone mixing ratios change for each of the three scenarios as the ambient NOx mixing ratio increases. The trajectories for the rainforest and oil palm scenarios correspond closely to those of Hewitt et al. [2]. For all scenarios, it is clear that NOx emission control is very important in order to ensure that ozone concentrations do not reach harmful levels. Even the VOC produced by natural rainforest can lead to harmful concentrations of ozone if NOx mixing ratios are allowed to enter the multi-ppbv range such as that found in rural Western Europe, North America and continental Asia [49,50]. VOC emissions from oil palm plantations, when combined with NOx concentrations typical of rural areas in the developed world, lead to potential peak ozone concentrations similar to those owing to heavy urbanization (not shown), indicating that significant air-quality issues may accompany large adoption of this crop in future unless tropical background NOx emissions are controlled [2]. However, not all crops have such potentially harmful effects on ozone formation. The trajectory for low BVOC-emitting crops such as soya [47], or sugar cane [48], has a very low ozone-forming potential.

(b). Global modelling studies

We have run several high-resolution (1° × 1°) three-dimensional model scenarios with p-TOMCAT, looking at the potential impact of land-use change in Borneo on local and regional atmospheric composition, to complement the box model studies presented in §4a. Measurements taken during the OP3 campaign showed that biogenic emissions of isoprene from oil palm plantations are significantly larger than from natural rainforest sites (see Fowler et al. [4]). In addition, the application of fertilizer at plantation sites and industrial processing and transport of oil palm will increase anthropogenic NOx emissions in oil palm regions. This was not measured directly but was confirmed indirectly during over-flights of both canopy types (see fig. 2 of Hewitt et al. [2]). Accordingly, several scenarios were run to explore the possible range of sensitivities.

The first, BASE, model scenario used surface anthropogenic emission datasets from ACCENT/IPCC AR4 [9] and seasonally and diurnally varying isoprene emissions taken from a present-day integration of the Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature (MEGAN v. 2.04 model [13]). A second present-day scenario, FOREST, replaced the MEGAN isoprene emissions over Borneo with observed diurnally varying forest isoprene fluxes from the OP3 campaign (table 1). As the temporal coverage of the measurements is too limited to provide any information on the seasonal cycle of the emissions, the seasonality of the MEGAN isoprene fluxes was applied to the FOREST scenario. The observed forest isoprene emissions were lower than those calculated by the MEGAN model (by approximately a factor of 4 at the Danum Valley) and produced modelled isoprene atmospheric concentrations that compare well with the observed atmospheric data. In comparison, the MEGAN fluxes overestimate observed isoprene mixing ratios in the Danum Valley.

The first of the land-use change scenarios, OILPALM1, considered a Borneo covered entirely in oil palm and assigned the OP3 oil palm isoprene fluxes to every Borneo grid box (table 1). The OP3 oil palm isoprene fluxes were significantly larger than both the OP3 forest and the MEGAN fluxes. All other emissions were unchanged from the BASE scenario. OILPALM2 included an increase in Borneo NOx emissions from industrial processing and fertilization of oil palm, in addition to the higher oil palm isoprene emissions. Table 2 summarizes the integrations. All integrations were forced with meteorological analyses from 2008.

Table 2.

A summary of the Borneo isoprene and NOx emission scenarios used in the land-use change p-TOMCAT simulations. Global emissions outside Borneo are based on the ACCENT/IPCC AR4 datasets in all scenarios.

| scenario | isoprene emissions | NOx emissions |

|---|---|---|

| BASE | MEGAN | ACCENT/IPCC AR4 |

| FOREST | observed OP3 forest fluxes | ACCENT/IPCC AR4 |

| OILPALM1 | observed OP3 oil palm fluxes | ACCENT/IPCC AR4 |

| OILPALM2 | observed OP3 oil palm fluxes | calculated NOx emissions associated with fertilization and oil palm industry |

NOx emissions from fertilized soils were based on OP3 observations of N2O, as well as parametrizations of ratios of NO and N2O from croplands in South East Asia [51]. The emissions totalled 0.8 Mg(NO2) km−2 yr–1 and were emitted as annual pulse emissions decaying linearly over a two month period following fertilizer application to a background flux of 0.05 kg(NO2) km−2 yr–1. The time of fertilizer application varied randomly with model grid box. NOx emissions from industrial processing and transport were constant throughout the year and were calculated from estimates of the energy required to process oil palm and the type of fuel used. We assumed industrial processing energy requirements of 8 GJ tonne–1 (palm oil), and plantation cropping and local transport energy requirements of 3 GJ tonne–1 (palm oil) [52]. One hundred per cent of the energy required for transport and 75 per cent of the energy required for processing is believed to be supplied by fossil fuel, with the remainder being supplied by the burning of waste products, e.g. fibre and shells. Assuming a yield of 4 tonnes (palm oil) ha−1 yr–1 [52,53], we estimated industrial NOx emissions of 1.24 Mg(NO2) km−2 yr–1.

Figure 4 compares some of the p-TOMCAT results from these scenarios with the CiTTyCAT calculations. Two points representing the rainforest landscape (FOREST) and the oil palm landscape (OILPALM2) are plotted, and follow the same general trends seen in the box model calculations. The p-TOMCAT calculations have not been performed with as large a range of NOx concentrations as have been explored in the box model. We plan to perform these integrations in the future.

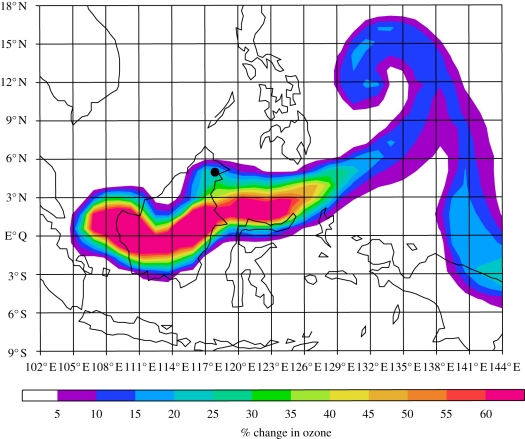

Figure 5 shows the percentage change in surface ozone between the FOREST and OILPALM2 emission scenarios for a day in May. The specified increases in isoprene and NOx emissions in OILPALM2 result in surface ozone increases of up to 80 per cent (approx. 15 ppb). Although in this model snap-shot absolute ozone mixing ratios do not exceed 34 ppb in the OILPALM2 scenario, modelled ozone shows significant temporal variability and, for example, exceeds 40 ppb at several times throughout the month at Danum. The largest changes are seen directly over Borneo; however, significant ozone increases occur downwind, the exact location of these changes depending on the day-to-day meteorology. Increases in modelled ozone are also seen in the free troposphere. For example, at about 5 km, the model calculates local O3 increases of up to 12 per cent (monthly mean for May). In this case, the largest increases in ozone are seen directly downwind of Borneo in a region corresponding to increased OH and NOx. Thus, although the largest changes are found locally, these calculations do suggest that the impact of land-use changes will not be confined to Borneo but that small changes will also occur throughout the free troposphere. Of course, only changes in emissions from Borneo have been considered. If changes over the tropics as a whole (Africa, South America, etc.) had been included, a larger free tropospheric response would be expected.

Figure 5.

The percentage change in surface ozone for a day in May modelled by p-TOMCAT between the FOREST and OILPALM2 scenarios (100 × (OILPALM2 – FOREST)/FOREST). Integrations were forced using meteorological analyses for 2008. Grid lines show a 3° × 3° grid; these calculations ran at a resolution of 1° × 1°. Bukit Atur is marked by the large filled circle.

It is important to recognize the exploratory nature of these experiments, whose aim is to explore sensitivities. For example, a landscape exclusively devoted to oil palm is clearly an extreme situation, but one which is useful for exploring one possible future air-quality trajectory. Similarly, §3 emphasized a number of chemical model uncertainties, which must caveat these calculations. However, recall that although there are discrepancies between observed and modelled surface composition, the calculated perturbations are much more robust to uncertainty in, for example, the details of chemical schemes (see §3b).

The above has considered the impact on atmospheric chemistry of emission changes, based on land-use change. Emissions of isoprene depend on a variety of factors. There is a well-known dependence on light and temperature, higher temperatures producing higher emissions up to a maximum at approximately 40°C [12,13]. Recently, a dependence on CO2 concentrations has also been shown [54,55], in this case producing a decrease in emissions for CO2 levels above today's ambient value (approx. 385 ppmv). The overall impact of climate change on isoprene emissions is then a balance of the changes in light (through changes in cloud cover), temperature and CO2. So, to understand future changes in atmospheric composition, we need to assess the relative changes in emissions owing to land-use change, to temperature and to CO2. To this end, a regional climate model (PRECIS) and a biogenic emission model (BVOCEM) were used in combination to investigate the impact of climate change and land-use change on biogenic emissions in South East Asia [56], but the further impact on atmospheric chemistry of these particular scenarios has not yet been explored.

Extrapolating current land-use change rates into the future, the study, using the A2 SRES scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), predicts that the present-day (2008) annual mean leaf-area index (LAI) will decrease by 36.9 per cent in 2100, mainly owing to conversion of tropical forest (evergreen broadleaf trees) into agriculture (i.e. oil palm and paddy) and other land-use types. Modelled temperatures rose across the region by about 3°C. Future changes in other climatic variables, such as precipitation and boundary layer depth, showed a high degree of variability.

For the PRECIS/BVOCEM simulations, projected climate changes, without projected land-use change or the CO2 emissions factor, showed an increase in isoprene emissions by 27 per cent (2100 relative to 2008). In the same scenario, but now including the CO2 emissions factor, isoprene emissions were found to be inhibited by 8 per cent. Thus, the negative effect of elevated CO2 on isoprene emissions overwhelmed the positive effect of climate change alone. Adding projected land-use change to the combined effects of climate change and the CO2 emissions factor produced a decrease in future isoprene emissions of 66 per cent. Land-use forcing alone accounted for a decrease in isoprene emissions of 5 per cent when the CO2 emissions factor was included, compared with an increase in isoprene emissions of 9 per cent without the CO2 emissions factor.

These results suggest that future emissions of isoprene in the region would be largely buffered by a number of competing factors, making the future isoprene emissions in the region, and their impact on atmospheric chemistry, difficult to predict accurately.

5. Role of halogen species

We have known for several decades that long-lived, anthropogenic halogen species are important for stratospheric chemistry. Indeed, these compounds are directly implicated in stratospheric ozone loss, both in polar latitudes (the ‘ozone hole’) and globally (see [57] for a detailed discussion), and these changes have important consequences for climate. The major long-lived gases are now regulated by the Montreal Protocol and their atmospheric abundances have started to decline [57]. However, additional short-lived bromine compounds (perhaps 4–6 ppt) seem to be required to balance the bromine budget in the lower stratosphere [57,58]. In tropical latitudes, deep convection could potentially lift natural, locally emitted halogenated species to the upper troposphere/lower stratosphere region, on timescales shorter than the species' lifetime. Photolysis, or oxidation reactions, would then release the active halogen atoms, which could contribute to stratospheric ozone depletion. Transport from the lower atmosphere into the tropical tropopause layer is most rapid over the Maritime Continent (e.g. [59]), so that transport of short-lived species to the stratosphere is likely to be most effective from this region. Characterizing the background concentrations of these short-lived compounds, and their variability, in South East Asia is an important research objective and one to which OP3 research has contributed.

In contrast to the stratosphere, our understanding of the role of halogens in the global troposphere is still evolving rapidly. It has been clear for some years that brominated compounds are responsible for sporadic, rapid ozone depletion in the polar boundary layer [60], and there is now a significant body of evidence indicating a wider role for reactive halogen chemistry throughout the remote oceanic boundary layer in tropical and middle latitudes and perhaps in the global free troposphere [61–64].

Understanding the sources of these reactive species, and their global implications, is now a major research question. The main known sources of reactive bromine and iodine species to the troposphere are emissions of organic halocarbons from macroalgae [65] and sea salt aerosol which provides the largest source of bromine [66]. There is also some evidence that the rainforest might provide a small natural source. Short-lived halocarbons in particular are still poorly understood in terms of their global fluxes. For example, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) [57] report emission estimates for bromoform ranging from 200 Gg Br yr−1 to over 1000 Gg Br yr−1. It is clear that more work is required to understand the wide range of estimates and to narrow that range.

The role of halogens could change in the future. The oceanic halocarbon sources probably depend on ocean temperature as well as on climate-dependent biological processes, and ocean sources of the halocarbons depend on wind-stress on the ocean surface (e.g. [67]), which could all change in the future. The transport routes, and rates, from source to sink could also change in a future climate. For example, simple calculations suggest an increase in the convective transport of short-lived, ozone-depleting halogens to the lowermost stratosphere later this century [68]. An additional factor is the rapidly developing seaweed industry with, for example, now more than 1500 ha of seaweed farms around Semporna, off the northeast coast of Sabah [1]. This is a potentially important ‘sea use’ change, analogous to changes occurring over land, which may have important consequences of fluxes of reactive gases into the atmosphere.

Several groups made measurements of halocarbons during OP3 [2], which we report here. We consider two example studies, the first of which [69] has explored the source strength of bromoform in South East Asia and the second has determined the total amount of short-lived bromine in the boundary layer of the Maritime Continent, which could potentially be lifted in deep convection towards the stratosphere.

6. Halocarbon measurements

Continuous measurements of a range of halocarbons (chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to very short-lived halocarbons) were made during OP3 using gas chromatographs with electron capture (GC–ECD) and mass spectrometer (GC-MS) detectors. Two µDirac GC-ECDs [70] were used in Sabah: one was based at the Bukit Atur global atmospheric watch (GAW) site in the Danum Valley, and the other was used in a series of short, exploratory deployments at different locations in the rainforest as well as at the coastal town of Kunak [69]. Measurements were made in two periods from April to August 2008. Halocarbons (including short-lived tracers having biogenic and anthropogenic sources) are measured with precisions ranging from ±1 (CCl4) to ±9 per cent (CH3I). Approximately 35–40 atmospheric samples are taken each day, which are interspersed with a programme of calibration gas samples and blank runs. The calibration gas used is from an NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory standard collected and calibrated in December 2005. Typical uncertainty in the calibration gas is ±0.5 to ±2 per cent (2 s.d.) for the CFCs and other long-lived halocarbons and ±5 to ±20 per cent for the short-lived halocarbons (B. D. Hall 2010, personal communication). A GC-MS system operating primarily in negative ion chemical ionization mode [71] was co-located at Bukit Atur making measurements during both periods, while a second GC-MS was used to analyse the whole air samples collected on the BAe-146 aircraft during the July detachment [72]. The ground-based GC-MS measurements were taken at hourly intervals with a typical precision of less than ±5 per cent. Calibrations were performed every eight samples using a high-pressure working standard which was calibrated before and after the campaign against the ‘NOAA 2003’ scale for CHBr3, CH2Br2 and CH3Br, and the ‘NOAA 2004’ scale for CH3I, with similar uncertainties to those reported above (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccl/scales.html). Calibrations for the other bromochlorocarbons are based on a University of East Anglia scale [73].

(a). Variability in CHBr3

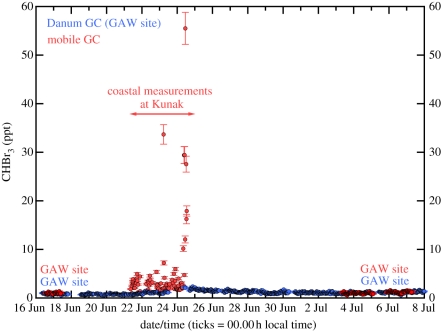

CHBr3 measured at Bukit Atur during OP3 ranged from about 0.6 to 3 ppt, with most measurements around 1 ppt (see Pyle et al. [69] for much more detail). Good consistency was found between the two µDirac GC-ECDs and the GC-MS measurements. One of the µDirac instruments made measurements at various locations around the Danum Valley site in an attempt to study variability, including the possibility of local sources. There is no clear signal of the latter but investigations are continuing.

One of the µDiracs was also deployed for a few days at Kunak, located about 50 km from Bukit Atur at a coastal site on a bay rich in macroalgae. Measurements from the two instruments during this period are shown in figure 6. The coastal measurements have quite a different distribution to those made at Bukit Atur. Background measurements range between 2 and 5 ppt, with more variability than at the Bukit Atur. In addition, there are a small number of excursions to much higher concentrations of up to 60 ppt, which occur when the local wind is onshore and is most likely owing to sampling of very local sources.

Figure 6.

Concentration of CHBr3 (ppt) measured at Danum Valley and Kunak by the µDirac GC. Blue symbols indicate measurements with the instrument deployed throughout at Danum Valley. Red symbols are concentrations measured by the instrument which was deployed at Kunak between 21 and 25 June, but otherwise was at Danum Valley. Reproduced with permission from Pyle et al. [69].

These data have been analysed using a range of numerical models, in an attempt to explain the possible sources and the origin of the gradient between the coast and the Bukit Atur site. The models confirm that during this period, the air measured at the sites had crossed biologically rich oceanic and coastal regions, the likely source regions. Small differences in transport, and different proximity to sources, can explain the different background concentrations.

With a short lifetime for CHBr3 of about two weeks, it is not possible to determine a global source strength just from measurements at one location. A network of sites, especially in the tropics, is required. However, a local South East Asian source magnitude can be derived from the OP3 data, amounting to somewhere between 21 and 50 Gg CHBr3 yr–1. These are reductions compared with a previous estimate [74]. Given the importance of the Maritime Continent for global halogen sources and transport, this new range of values for the local source strength provides an important constraint on overall global emissions; our best estimate is now 382 Gg CHBr3 yr–1, compared with probable upper and lower limits from about 400 to 595 Gg CHBr3 yr–1 in Warwick et al. [74] and the much wider range in WMO [57].

Following OP3, one of the µDirac GC-ECDs has remained at Bukit Atur and the other has been moved to Tawau, a coastal location about 70 km due south of Bukit Atur. More than 2 years of quasi-continuous measurements of a range of halocarbons have now been collected. These measurements are being complemented by new tropical deployments of µDirac, which will allow an improved estimate of source strength and variability to be made.

(b). Total available bromine

The total amount of bromine present in organic forms is an important factor for stratospheric and tropospheric halogen chemistry as it represents the amount of bromine that can be released to take part in the atmospheric chemistry. During July 2008, five bromine-containing species were measured by GC-MS at the Danum Valley: CHBr3, CH2Br2, CHBrCl2, CHBr2Cl and CH2BrCl. The summed mixing ratios of the bromine in these compounds varied between 5 and 10 ppt with a mean of 7 ppt. Over 90 per cent of this was present as CHBr3, CH2Br2 or CHBrCl2.

These values place some constraint on the total concentration of short-lived bromine species which could be lifted into the lower stratosphere. Detailed modelling will be required to assess how much of this could reach the stratosphere. In addition, the variability discussed in §6a needs to be considered, and for a stronger constraint the entire annual cycle should be considered, ideally from a number of tropical locations. The amount reaching the stratosphere could change in the future and will depend on changes in both the emissions (e.g. owing to increased seaweed farming) and the speed of transport (e.g. enhanced convection). Both these processes could change in a future climate; further research into the fundamental processes is required.

7. Conclusions

We have presented some results from the OP3 campaign in Sabah during 2008 that allow us to study the impact of local changes at the regional scale. Local measurements of atmospheric composition have been investigated in the context of box and global models. The importance of a correct representation of physical processes (mixing, deposition and emissions) has been highlighted.

Model studies of land-use change confirm the earlier study of Hewitt et al. [2]. Further changes to an intensive oil palm agriculture in South East Asia, and the tropics in general, could have important impacts on air quality, with the biggest factor being the concomitant changes in NOx emissions. With large increases in NOx and VOCs, large ozone changes are predicted. With the particular emission scenarios developed, global model calculations suggest that a local increase in ozone of around 50 per cent could occur. Smaller impacts in the free troposphere are also calculated. As in many other cases of changes in industrial practice, a full environmental life cycle of the impact of land-use changes is essential.

The Maritime Continent is a region of very strong deep convection, such that even short-lived species could potentially be lifted towards the lower stratosphere. Measurements of short-lived brominated compounds around Sabah suggest the importance of oceanic (and, especially, coastal) sources. High concentrations were frequently measured when the local atmospheric circulation over regions of high potential emissions confined air in the local boundary layer, allowing concentrations to build up with time. The global importance of these concentrations (e.g. 10 s of ppt of CHBr3) relative to the much lower background (e.g. 1–2 of ppt of CHBr3) remains to be determined. Based on the background values, total short-lived bromine concentrations measured at the surface during OP3 amount to about 7 ppt, putting some constraint on the amount of these species that can reach the lower stratosphere.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Malaysian and Sabah Governments for their permission to conduct research in Malaysia; the Malaysian Meteorological Department (MMD, now Met Malaysia) for access to the Bukit Atur Global Atmosphere Watch station and their long-term ozone record. For all their assistance with the fieldwork, we gratefully acknowledge: Waidi Sinun of Yayasan Sabah and his staff; Dr Glen Reynolds and his staff at the Royal Society's Danum Valley Research Centre; the ground staff, engineers, scientists and pilots of the UK Natural Environment Research Council/UK Meteorological Office's BAe 146-301 large atmospheric research aircraft (FAAM); and the rest of the OP3 project team for their individual and collective efforts. This research was funded by NCAS, by NERC under the OP3 (grant ref: NE/D002117/1) and ACES (grant ref: NE/E011233/1) projects. This work was also supported by a British Council PMI2 grant. N.R.P.H. thanks NERC for his Advanced Fellowship (NE/G014655/1). We acknowledge data from AATSR World Fire Atlas from the Data User Element of the European Space Agency.

This paper constitutes Publication no. 513 of the Royal Society South East Asia Rainforest Research Programme.

References

- 1.Phang S. M. 2006. Seaweed Resources in Malaysia: Current status and future prospects. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manage. 9, 185–202 10.1080/14634980600710576 (doi:10.1080/14634980600710576) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt C. N., et al. 2009. Nitrogen management is essential to prevent tropical oil palm plantations from causing ground-level ozone pollution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18 447–18 451 10.1073/pnas.0907541106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0907541106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt C. N., et al. 2010. Overview: oxidant and particle photochemical processes above a south-east Asian tropical rainforest (the OP3 project): introduction, rationale, location characteristics and tools. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 169–199 10.5194/acp-10-169-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-169-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler D., et al. 2011. Effects of land use on surface–atmosphere exchanges of trace gases and energy in Borneo: comparing fluxes over oil palm plantations and a rainforest. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 3196–3209 10.1098/rstb.2011.0055 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0055) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKenzie A. R., et al. 2011. The atmospheric chemistry of trace gases and particulate matter emitted by different land uses in Borneo. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 3177–3195 10.1098/rstb.2011.0053 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu S., Trainer M., Fehsenfeld F., Parrish D., Williams E., Fahey D., Hübler G., Murphy P. 1987. Ozone production in the rural troposphere and the implications for regional and global ozone distributions. J. Geophys. Res. 92, 4191–4207 10.1029/JD092iD04p04191 (doi:10.1029/JD092iD04p04191) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sillman S. 1995. The use of NOy, H2O2, and HNO3 as indicators for ozone-NOx-hydrocarbon sensitivity in urban locations. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 14 175–14 188 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prather M., et al. 2003. Fresh air for the 21st century? Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1100. 10.1029/2002GL016285 (doi:10.1029/2002GL016285) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson D. S., et al. 2006. Multimodel ensemble simulations of present-day and near-future tropospheric ozone. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D08301. 10.1029/2005JD006338 (doi:10.1029/2005JD006338) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler D., et al. 2008. Ground-level ozone in the 21st century: future trends, impacts and policy implications. Royal Society Policy Document, 132pp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh H. B., Zimmerman P. 1992. Atmospheric distributions and sources of nonmethane hydrocarbons. In Gaseous pollutants: characterization and cycling (ed. Nriagu J.), pp. 177–235 New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guenther A., et al. 1995. A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 8873–8892 10.1029/94JD02950 (doi:10.1029/94JD02950) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guenther A., Karl T., Harley P., Wiedinmyer C., Palmer P. I., Geron C. 2006. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3181–3210 10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006 (doi:10.5194/acp-6-3181-2006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kesselmeier J., Staudt M. 1999. Biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOC): an overview of emission, physiology and ecology. J. Atmos. Chem. 33, 23–88 10.1023/A:1006127516791 (doi:10.1023/A:1006127516791) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arneth A., Monson R. K., Schurgers G., Niinemets Ü., Palmer P. I. 2008. Why are estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions so similar (and why is this not so for monoterpenes)? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 4605–4620 10.5194/acp-8-4605-2008 (doi:10.5194/acp-8-4605-2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crutzen P. J., Mosier A. R., Smith K. A., Winiwarter W. 2008. N2O release from agro-biofuel production negates global warming reduction by replacing fossil fuels. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 389–395 10.5194/acp-8-389-2008 (doi:10.5194/acp-8-389-2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langford B., Misztal P. K., Nemitz E., Davison B., Helfter C., Pugh T. A. M., MacKenzie A. R., Lim S. F., Hewitt C. N. 2010. Fluxes and concentrations of volatile organic compounds from a South-East Asian tropical rainforest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 8391–8412 10.5194/acp-10-8391-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-8391-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misztal P. K., et al. 2010. Large estragole fluxes from oil palms in Borneo. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 4343–4358 10.5194/acp-10-4343-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-4343-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelieveld J., et al. 2007. Atmospheric oxidation capacity sustained by a tropical forest. Nature 452, 737–740 10.1038/nature06870 (doi:10.1038/nature06870) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pugh T. A. M., et al. 2010. Simulating atmospheric composition over a South-East Asian tropical rainforest: performance of a chemistry box model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 279–298 10.5194/acp-10-279-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-279-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer P. I., Jacob D. J., Fiore A. M., Martin R. V., Chance K., Kurosu T. P. 2003. Mapping isoprene emissions over North America using formaldehyde column observations from space. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4180. 10.1029/2002JD002153 (doi:10.1029/2002JD002153) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu T. M., Jacob D. J., Palmer P. I., Chance K., Wang Y. X., Barletta B., Blake D. R., Stanton J. C., Pilling M. J. 2007. Space-based formaldehyde measurements as constraints on volatile organic compound emissions in east and south Asia and implications for ozone. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D06312. 10.1029/2006JD007853 (doi:10.1029/2006JD007853) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levelt P. F., van den Oord G. H. J., Dobber M. R., Malkki A., Visser H., de Vries J., Stammes P., Lundell J. O. V., Saari H. 2006. The ozone monitoring instrument. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 44, 1093–1101 10.1109/TGRS.2006.872333 (doi:10.1109/TGRS.2006.872333) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arino O., Plummer S., Defrenne D. 2005. Fire disturbance: the ten years time series of the ATSR World Fire Atlas. In Proc. MERIS-AATSR Workshop 2005, Frascati, Italy, September, 2005 European Space Agency. http://due.esrin.esa.int/wfareferences.php [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Smedt I., Müller J.-F., Stavrakou T., van der A. R., Eskes H., Van Roozendael M. 2008. Twelve years of global observations of formaldehyde in the troposphere using GOME and SCIAMACHY sensors. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 4947–4963 10.5194/acp-8-4947-2008 (doi:10.5194/acp-8-4947-2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin R. V., et al. 2002. An improved retrieval of tropospheric nitrogen dioxide from GOME. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 4437. 10.1029/2001JD001027 (doi:10.1029/2001JD001027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arino O., Simon M., Piccolini I., Rosaz J. M. 2001. The ERS-2 ATSR-2 World Fire Atlas and the ERS-2 ATSR-2 World Burnt Surface Atlas projects. In Proc. 8th ISPRS Conf. on Physical Measurement and Signatures in Remote Sensing, Aussois, France, 8–12 January, 2001 European Space Agency. http://due.esrin.esa.int/wfareferences.php [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barkley M. P., Palmer P. I., De Smedt I., Karl T., Guenther A., Van Roozendael M. 2009. Regulated large-scale annual shutdown of Amazonian isoprene emissions? Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L04803. 10.1029/2008GL036843 (doi:10.1029/2008GL036843) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wild O., Law K. S., McKenna D. S., Bandy B. J., Penkett S. A., Pyle J. A. 1996. Photochemical trajectory modelling studies of the North Atlantic region during August 1993. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 29 269–29 288 10.1029/96JD00837 (doi:10.1029/96JD00837) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone D., et al. 2011. Isoprene oxidation mechanisms: measurements and modelling of OH and HO2 over a South-East Asian tropical rainforest during the OP3 field campaign. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 6749–6771 10.5194/acpd-11-6749-2011 (doi:10.5194/acpd-11-6749-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peeters J., Nguyen T. L., Vereecken L. 2009. HOx radical regeneration in the oxidation of isoprene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 11, 5935–5939 10.1039/b908511d (doi:10.1039/b908511d) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh T., Ryder J., MacKenzie A., Moller S., Lee J., Helfter C., Nemitz E., Lowe D., Hewitt C. 2011. Modelling chemistry in the nocturnal boundary layer above tropical rainforest and a generalised effective nocturnal ozone deposition velocity for sub-ppbv NOx conditions. J. Atmos. Chem. 65, 89–110 10.1007/s10874-011-9183-4 (doi:10.1007/s10874-011-9183-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misztal P. K. 2010. Concentrations and fluxes of atmospheric biogenic volatile organic compounds by proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, UK [Google Scholar]

- 34.Misztal P. K., et al. 2011. Direct ecosystem fluxes of volatile organic compounds from oil palms in South-East Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 11, 12 671–12 724. (doi:10.5194/acpd-11-12671-2011) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karl T., Harley P., Emmons L., Thornton B., Guenther A., Basu C., Turnispeed A., Jardine K. 2010. Atmospheric cleansing of oxidized organic trace gases by vegetation. Science 330, 816–819 10.1126/science.1192534 (doi:10.1126/science.1192534) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pike R. C., et al. 2010. NOx and O3 above a tropical rainforest: an analysis with a global and box model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 10 607–10 620 10.5194/acp-10-10607-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-10607-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Archibald A. T., et al. 2011. Impacts of HOx regeneration and recycling in the oxidation of isoprene: Consequences for the composition of past, present and future atmospheres. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, (doi:10.1029/2010GL046520) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peeters J., Müller J.-F. 2010. HOx radical regeneration in isoprene oxidation via peroxy radical isomerisations. II: experimental evidence and global impact. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 14 227–14 235 10.1039/c0cp00811g (doi:10.1039/c0cp00811g) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Archibald A. T., Cooke M. C., Utembe S. R., Shallcross D. E., Derwent R. G., Jenkin M. E. 2010. Impacts of mechanistic changes on HOx formation and recycling in the oxidation of isoprene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 8097–8118 10.5194/acp-10-8097-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-8097-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofzumahaus A., et al. 2009. Amplified trace gas removal in the troposphere. Science 324, 1702–1704 10.1126/science.1164566 (doi:10.1126/science.1164566) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whalley L. K., et al. 2011. Quantifying the magnitude of a missing hydroxyl radical source in a tropical rainforest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 7223–7233 10.5194/acp-11-7223-2011 (doi:10.5194/acp-11-7223-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voulgarakis A., Savage N. H., Wild O., Carver G. D., Clemitshaw K. C., Pyle J. A. 2009. Upgrading photolysis in the p-TOMCAT CTM: model evaluation and assessment of the role of clouds. Geosci. Model Dev. 2, 59–72 10.5194/gmd-2-59-2009 (doi:10.5194/gmd-2-59-2009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voulgarakis A., Savage N. H., Wild O., Braesicke P., Young P. J., Carver G. D., Pyle J. A. 2010. Interannual variability of tropospheric composition: the influence of changes in emissions, meteorology and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 2491–2506 10.5194/acp-10-2491-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-2491-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson G., Davies F., Collier C. 2010. Remote sensing of the tropical rain forest boundary layer using pulsed Doppler lidar. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 5891–5901 10.5194/acp-10-5891-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-5891-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Connor F. M., Carver G. D., Savage N. H., Pyle J. A., Methven J., Arnold S. R., Dewey K., Kent J. 2005. Comparison and visualisation of high resolution transport modelling with aircraft measurements. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 6, 164–170 10.1002/asl.111 (doi:10.1002/asl.111) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohara T., Akimoto H., Kurokawa J., Horii N., Yamaji K., Yan X., Hayasaka T. 2007. An Asian emission inventory of anthropogenic emission sources for the period 1980–2020. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4419–4444 10.5194/acp-7-4419-2007 (doi:10.5194/acp-7-4419-2007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lamb B., Gay D., Westberg H., Pierce T. 1993. A biogenic hydrocarbon emission inventory for the USA using a simple forest canopy model. Atmos. Environ. 27A, 1673–1690 10.1016/0960-1686(93)90230-V (doi:10.1016/0960-1686(93)90230-V) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen R. A. 1978. Isoprene plant species list. Special Report of the Air Pollution Research Section Washington State University Pullman, Pullman, WA, USA [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins W. J., Stevenson D. S., Johnson C. E., Derwent R. G. 1997. Tropospheric ozone in a global-scale 3-dimensional Lagrangian model and its response to NOx emission controls. J. Atmos. Chem. 26, 223–274 10.1023/A:1005836531979 (doi:10.1023/A:1005836531979) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarrason L., Nyiri A. () 2008. Transboundary acidification, eutrophication and ground level ozone in Europe in 2006. European Monitoring and Evaluation Programme Status Report 1, Oslo [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan X. Y., Akimoto H., Ohara T. 2003. Estimation of nitrous oxide, nitric oxide and ammonia emissions from croplands in East, Southeast and South Asia. Global Change Biol. 9, 1080–1096 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00649.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00649.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reijnders L., Huijbregts M. A. J. 2008. Palm oil and the emission of carbon-based greenhouse gases. J. Cleaner Prod. 16, 477–482 10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.07.054 (doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.07.054) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.MPOA (Malaysian Palm Oil Association). 2005. Annual Report 2005. Kuala Lumpur; See www.mpoa.org.my [Google Scholar]

- 54.Possell M., Hewitt C. N. 2009. Gas exchange and photosynthetic performance of the tropical tree Acacia nigrescens when grown in different CO2 concentrations. Planta 229, 837–846 10.1007/s00425-008-0883-1 (doi:10.1007/s00425-008-0883-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Possell M., Hewitt C. N., Beerling D. J. 2005. The effects of glacial atmospheric CO2 concentrations and climate on isoprene emissions by vascular plants. Global Change Biol. 11, 60–66 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00889.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00889.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sentian J., MacKenzie A. R., Hewitt C. N. 2011. The regional biogenic emissions response to climate changes and ambient CO2, in Southeast Asia. Int. J. Climate Change: Impacts and Responses 2, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Meteorological Organization (WMO). 2007. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2007. Global ozone research and monitoring project. Report no. 50, World Meteorological Organization, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salawitch R. J., Weisenstein D. K., Kovalenko L. J., Sioris C. E., Wennberg P. O., Chance K., Ko M. K. W., McLinden C. A. 2005. Sensitivity of ozone to bromine in the lower stratosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L05811. 10.1029/2004GL021504 (doi:10.1029/2004GL021504) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levine J. G., Braesicke P., Harris N. R. P., Pyle J. A. 2008. Seasonal and inter-annual variations in troposphere-to-stratosphere transport from the tropical tropopause layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 3689–3703 10.5194/acp-8-3689-2008 (doi:10.5194/acp-8-3689-2008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrie L. A., Bottenheim J. W., Schnell R. C., Crutzen P. J., Rasmussen R. A. 1988. Ozone destruction and photochemical-reactions at polar sunrise in the lower arctic atmosphere. Nature 334, 138–141 10.1038/334138a0 (doi:10.1038/334138a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagao I., Matsumoto K., Tanaka H. 1999. Sunrise ozone destruction found in the sub-tropical marine boundary layer. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3377–3380 10.1029/1999GL010836 (doi:10.1029/1999GL010836) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Read K. A., et al. 2008. Extensive halogen-mediated ozone destruction over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Nature 453, 1232–1235 10.1038/nature07035 (doi:10.1038/nature07035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mahajan A. S., Plane J. M. C., Oetjen H., Mendes L., Saunders R. W., Saiz-Lopez A., Jones C. E., Carpenter L. J., McFiggans G. B. 2010. Measurement and modelling of tropospheric reactive halogen species over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 4611–4624 10.5194/acp-10-4611-2010 (doi:10.5194/acp-10-4611-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Allan B. J., McFiggans G., Plane J. M. C., Coe H. 2000. Observations of iodine monoxide in the remote marine boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 14 363–14 369 10.1029/1999JD901188 (doi:10.1029/1999JD901188) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carpenter L. J., Liss P. S. 2000. On temperate sources of bromoform and other reactive bromine gases. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 20 539–20 547 10.1029/2000JD900242 (doi:10.1029/2000JD900242) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sander R., et al. 2003. Inorganic bromine in the marine boundary layer: a critical review. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 3, 1301–1336 10.5194/acp-3-1301-2003 (doi:10.5194/acp-3-1301-2003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang X., Cox R. A., Warwick N. J., Pyle J. A., Carver G. D., O'Connor F. M., Savage N. H. 2005. Tropospheric bromine chemistry and its impacts on ozone: a model study. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D23311. 10.1029/2005JD006244 (doi:10.1029/2005JD006244) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dessens O., Zeng G., Warwick N., Pyle J. 2009. Short-lived bromine compounds in the lower stratosphere; impact of climate change on ozone. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 10, 201–206 10.1002/asl.236 (doi:10.1002/asl.236) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pyle J. A., et al. 2011. Bromoform in the tropical boundary layer of the Maritime Continent during OP3. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 529–542 10.5194/acp-11-529-2011 (doi:10.5194/acp-11-529-2011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gostlow B., Robinson A. D., Harris N. R. P., O'Brien L. M., Oram D. E., Mills G. P., Newton H. M., Yong S. E., Pyle J. A. 2010. µ-Dirac: an autonomous instrument for halocarbon measurements. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 507–521 10.5194/amt-3-507-2010 (doi:10.5194/amt-3-507-2010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Worton D. R., Mills G. P., Oram D. E., Sturges W. T. 2007. Gas chromatography negative ion chemical ionisation mass spectrometry: application to the detection of alkyl nitrates and halocarbons in the atmosphere. J. Chromatogr. A 1201, 112–119 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.06.019 (doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2008.06.019) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Newton H. M., Reeves C. E., Mills G. P., Oram D. E. In preparation. Organohalogens in and above the rainforest of Borneo. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sturges W. T., McIntyre H. P., Penkett S. A., Chappellaz J., Barnola J.-M., Mulvaney R., Atlas E., Stroud V. 2001. Methyl bromide, other brominated methanes and methyl iodide in polar firn air. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 1595–1606 10.1029/2000JD900511 (doi:10.1029/2000JD900511) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Warwick N. J., Pyle J. A., Carver G. D., Yang X., Savage N. H., O'Connor F. M., Cox R. A. 2006. Global modeling of biogenic bromocarbons. J. Geophys. Res 111, D24305. 10.1029/2006JD007264 (doi:10.1029/2006JD007264) [DOI] [Google Scholar]