Abstract

Summary: High-throughput DNA sequencing technologies have spurred the development of numerous novel methods for genome assembly. With few exceptions, these algorithms are heuristic and require one or more parameters to be manually set by the user. One approach to parameter tuning involves assembling data from an organism with an available high-quality reference genome, and measuring assembly accuracy using some metrics.

We developed a system to measure assembly quality under several scoring metrics, and to compare assembly quality across a variety of assemblers, sequence data types, and parameter choices. When used in conjunction with training data such as a high-quality reference genome and sequence reads from the same organism, our program can be used to manually identify an optimal sequencing and assembly strategy for de novo sequencing of related organisms.

Availability: GPL source code and a usage tutorial is at http://ngopt.googlecode.com

Contact: aarondarling@ucdavis.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data is available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Given high-throughput sequencing data, most current genome assemblers apply deterministic heuristics to infer the genome sequence. Usually a variety of parameters can be used to control the heuristic, for which the optimal combination of values may not be obvious. Given a training dataset consisting of high-quality reference genomes and sequence reads generated from those genomes, it may be possible to manually or automatically select a good set of assembly parameters. A key requirement for this task is a means to quantify the accuracy of an assembly.

Measuring the accuracy with which an assembly reconstructs the reference genome presents another inference problem. It is usually unknown which part of the inferred assembly corresponds to which part of the reference genome. We must somehow map parts of the assembly back onto the reference genome through sequence alignment, which usually takes one of two forms: local alignment, exemplified by algorithms like BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997), and whole genome alignment with algorithms like MUMmer (Kurtz et al., 2004) or Mauve (Darling et al., 2004).

We introduce a new set of assembly accuracy metrics based on the progressiveMauve genome aligner (Darling et al., 2010). In our method, the assembly contigs and/or scaffolds are first reordered to match a reference genome with the Mauve Contig Mover (Rissman et al., 2009). The ordered, aligned assembly is then compared to the reference to identify differences.

Our method is most closely related to MUMmer's dnadiff program, which can measure assembly errors using genome alignment (Phillippy et al., 2008). We, however, use a different alignment heuristic and evaluate some new types of error such as rearrangement distance. Several ongoing efforts are directed at measuring assembly accuracy on particular datasets, including the Assemblathon, GAGE and dnGASP. These initiatives use tools like dnadiff, the Mauve Assembly Metrics, and others.

2 METHODS

In the present work we summarize differences in a pairwise alignment of the assembly and reference genome [e.g. as computed by progressiveMauve (Darling et al., 2010)]. We illustrate this process by way of example. Given the following reference genome and assembled genome:

Reference: AGGCTAGCGCGCGATTAGGATC

Assembly: AGTAGCGGGCCGATTAAGANC

A genome alignment of the reference and assembly might look like:

Reference: AGGCTAGCGCG-CGATTAGGATC

Assembly: AG–TAGCGGGCCGATTAAGANC

From this alignment, we would calculate the assembly scoring metrics as follows (not an exhaustive list of metrics):

Miscalled bases: 2 (C→G and G→A)

Uncalled bases: 1 (N)

Extra bases: 1 (Insertion of C in assembly)

Missing bases: 2 (Deletion of GC in assembly)

Number of extra segments: 1

Number of missing segments: 1

In addition to metrics summarizing the number of base miscalls, missing and extra segments (each also evaluated by dnadiff), our method produces a variety of other metrics. The location of miscalled bases, missing segments and extra segments is exported to a tab-delimited text file for subsequent analysis. GC content of the missing and extra regions is also exported. Misassemblies are identified as rearrangement breakpoints inside of contigs. The double cut and join (DCJ) distance (Bergeron et al., 2006) between the assembly and reference is calculated to estimate the combined effect of misassembly and lack-of-assembly errors (excess contig breaks) on rearrangement distance. Finally each protein coding sequence in the reference genome is checked in the assembly for whether it yields an intact coding sequence, with types and location of substitution and frameshift errors reported.

2.1 Assembling genomes of Haloarchaea

In an ongoing effort, we are sequencing de novo the genomes of 60 halophilic archaea. Four of these organisms have high-quality reference genomes completed independently of our project. We elected to demonstrate our new assembly metrics on one of these organisms, Haloferax volcanii strain DS2. This organism has a 4.0 Mbp genome organized into five circular replicons with about 100 repetitive IS elements of 1–2 Kbp each (Hartman et al., 2010). Using 454 and Illumina resequencing data, we generated three different assemblies to compare with our software. The assemblies are named volc454, volcV and volcIDBA (see Supplementary Material for sequencing and assembly details).

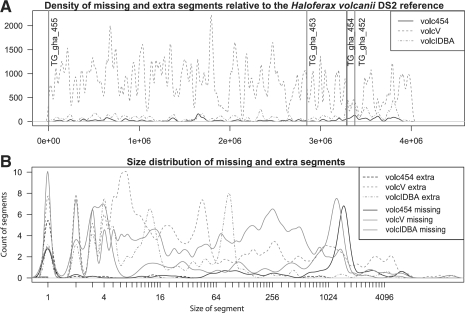

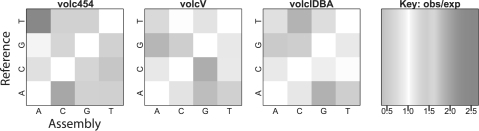

We scored each assembly against the reference genome using the aforementioned method. An overview of each assembly's metrics is given in Table 1. The location of assembly errors is mapped on the H.volcanii DS2 reference genome in Figure 1. Finally, Figure 2 illustrates that each sequencing and assembly strategy appears to have bias in the direction of erroneous base calls.

Table 1.

Mauve assembly metrics for three assemblies of H.volcanii DS2

| Metric | volc454 | volcV | volcIDBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold count | 157 | 1394 | 50 |

| Miscalled bases | 81 | 948 | 235 |

| Uncalled bases | 0 | 53 899 | 15 188 |

| Extra bases (%) | 0.04 | 10.8 | 2.54 |

| Missing bases (%) | 3.13 | 5.87 | 2.71 |

| Extra segments | 43 | 1079 | 262 |

| Missing segments | 117 | 1144 | 192 |

| DCJ Distance | 114 | 909 | 61 |

| Intact CDS (%) | 99.3 | 87.8 | 97.3 |

Fig. 1.

(A) Density of extra and missing segments in the assemblies of H.volcanii DS2. Reference genome coordinates are given on the x-axis, and red vertical bars delineate the boundaries of the five circular replicons in the reference genome. (B) Size distribution of missing and extra segments in each assembly. The size of a missing segment is given on the x-axis, and the count of missing segments at that size on the y-axis.

Fig. 2.

Biased errors in the base calling of each assembly. Errors are not uniformly random in any of the three assemblies. See Supplementary Material for more details.

3 DISCUSSION

The assembly metrics we describe illustrate substantial differences between sequencing and assembly strategies. For example, the volc454 assembly captured nearly all coding genes in the reference genome, but had a high scaffold count relative to the volcIDBA assembly. Striking an ideal balance between assembly error types, rates and sequencing cost is an exercise left for users of our software.

When a finished reference genome is available and has been resequenced, the assembly metrics calculated by our system can be used to guide selection of sequencing strategy and tune assembly parameters. The reported metrics may form the basis for a future automated system to perform supervised machine learning of assembly parameters by conducting a parameter sweep over a large number of assembly strategies.

Finally, we note that genome alignment algorithms are not perfect and some differences between the assembly and the reference may be due to alignment error and not true assembly errors.

Funding: National Science Foundation award (ER 0949453).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Altschul S.F., et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron A., et al. A unifying view of genome rearrangements. In: Bucher P., Moret B.M.E., editors. WABI '06: Proceedings of the Sixth International Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Vol. 4175. Springer; 2006. pp. 163–173. ofLecture Notes in Computer Science. [Google Scholar]

- Darling A.C.E., et al. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling A.E., et al. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman A.L., et al. The complete genome sequence ofHaloferax volcaniiDS2, a model archaeon. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9605. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippy A., et al. Genome assembly forensics: finding the elusive mis-assembly. Genome Biol. 2008;9:1–13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-3-r55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman A.I., et al. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve Aligner. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2071–2073. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.